Abstract

Fatigue and sleep disturbances are two of the most common and distressing symptoms reported by cancer patients. Fatigue and sleep are also correlated with each other. While fatigue has been reported to be associated with some inflammatory markers, data about the relationship between cancer-related sleep disturbances and inflammatory markers are limited. This study examined the relationship between fatigue and sleep, measured both subjectively and objectively, and inflammatory markers in a sample of breast cancer patients before and during chemotherapy. Fifty-three women with newly diagnosed stage I–III breast cancer scheduled to receive at least four 3-week cycles of chemotherapy participated in this longitudinal study. Fatigue was assessed with the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF), sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and objective sleep was measured with actigraphy. Three inflammatory markers were examined: Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Data were collected before (baseline) and during cycle 1 and cycle 4 of chemotherapy. Compared to baseline, more fatigue was reported, levels of IL-6 increased and IL-1RA decreased during chemotherapy. Reports of sleep quality remained poor. Mixed model analyses examining changes from baseline to each treatment time point revealed overall positive relationships between changes in total MFSI-SF scores and IL-6, between changes in total PSQI scores and IL-6 and IL-1RA, and between total wake time at night and CRP (all p’s<0.05). These relationships suggest that cancer-related fatigue and sleep disturbances may share common underlying biochemical mechanisms.

Keywords: breast cancer, chemotherapy, fatigue, sleep, inflammatory markers

1. Introduction

Fatigue and sleep disturbances are two of the most common and distressing symptoms of patients with cancer. About 70%–80% of cancer patients complain of fatigue (Hofman et al., 2007) and 30% – 75% of newly diagnosed or recently treated cancer patients report sleep problems (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2001; Berger et al., 2005). Indeed, both cancer and cancer treatment-related fatigue are closely associated with both subjectively and objectively measured sleep problems (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2012; Roscoe et al., 2007).

In addition to the close relationship with sleep disturbances, cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is also associated with multiple other factors, including anemia, fever, pain, weight loss, medication, infection, and depression (Bardwell and Ancoli-Israel, 2008; Kurzrock, 2001). Sleep disturbances in cancer patients are also associated with multiple factors, such as depression, anxiety, treatment (e.g., chemotherapy and radiation), cancer treatment-induced hot flashes, pain, fatigue and changes of biological rhythms (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2001; Liu and Ancoli-Israel, 2008). CRF and sleep disturbances are both prominent components of a group of “sickness behaviors” originally reported in cancer patients receiving systemic administration of cytokines, such as interferon-α (IFN-α), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), for the treatment of the cancer (Kelley et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004).

On the other hand, elevated levels of cytokines have been reported in patients with different cancers (Mills et al., 2004; Mills et al., 2008; O'Hanlon et al., 2002; Rich et al., 2005). Cytokines, secreted by inflammatory leukocytes and some non-leukocytic cells, are non-antibody polypeptides that act as intercellular mediators and are mainly integral to the function of immune system. Cytokines are induced not only by infectious agents, but also by cancer cells. Elevated levels of certain cytokines have been found in blood, ascites, pleural effusions, and urine of patients with cancer. Since inflammation is recognized as a critical component of tumor progression, cytokines have become an important group of inflammatory markers of cancer and cancer treatment (Kurzrock, 2001; Opp, 2005).

A relationship between elevated inflammatory markers and fatigue was suggested a decade ago (Kurzrock, 2001), and has been a subject of recent studies (Bower et al., 2002; Bower et al,. 2011; Collado-Hidalgo et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2008; Mills et al., 2005; Schubert et al., 2007). Data from our laboratory revealed that elevated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) were related to increased fatigue in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy (Mills et al., 2005). Bower and colleagues found that fatigue in breast cancer survivors was associated with higher levels of plasma Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type II (sTNF-RII), neopterin and soluble interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor (Bower et al., 2002; Bower et al,. 2011; Collado-Hidalgo et al., 2006).

Cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α, may influence sleep regulatory functions in both normal sleep and particularly in sleep disorders (Opp, 2005; Raison et al., 2010; Vgontzas et al., 1997; Vgontzas et al., 2004). In addition, the relationship between sleep and inflammation may be bi-directional (Rich et al., 2005; Vgontzas et al., 1997). However, as Miller et al. (Miller et al., 2008) concluded in their review paper, the relationship between sleep and inflammatory markers in cancer has rarely been studied. While a relationship between IL-6 and serum soluble receptor 1 (sTNF-R1) for tumor necrosis factor in patients with lung cancer and cancer-treatment related symptoms including sleep problems was reported by Wang and colleagues; the sleep problem was only assessed as a part of a larger symptom inventory (Wang et al., 2010).

Our laboratory conducted a longitudinal study examining fatigue, sleep and circadian rhythms among women with breast cancer before and during chemotherapy. Based on preliminary data from the first 26 women enrolled in study, we previously reported that although the acute effect of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients was to reduce the circulating levels of sICAM-1 and VEGF, the cumulative effect of three cycles of treatment was to elevate levels of the two (Mills et al., 2004). In the same study, data from baseline and the end of cycle 3 of chemotherapy showed significant elevations in inflammatory markers related to endothelial and platelet activation, i.e., sICAM-1, VEGF, sP-selection and vWF (Mills et al., 2008), and the increased levels of sICAM-1 and VEGF were related to worse fatigue and quality of life (Mills et al., 2005). We also found that fatigue was associated with both subjective and objective sleep parameters during chemotherapy (Liu et al., 2012).

As infection-induced sleep alteration is possibly mediated by cytokines (Opp, 2005), and increased cytokines in cancer are mostly induced by cancer and cancer treatment (Wang et al., 2010), in this study our aim was to identify possible biological elements of both fatigue and sleep in breast cancer. We were now able to examine the complete data set in 53 women and focused on the predictive effects of three inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-1RA and CRP) on fatigue and sleep. We hypothesized that changes in fatigue and sleep (measured both subjectively and objectively) would be related to changes in biomarkers over time.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

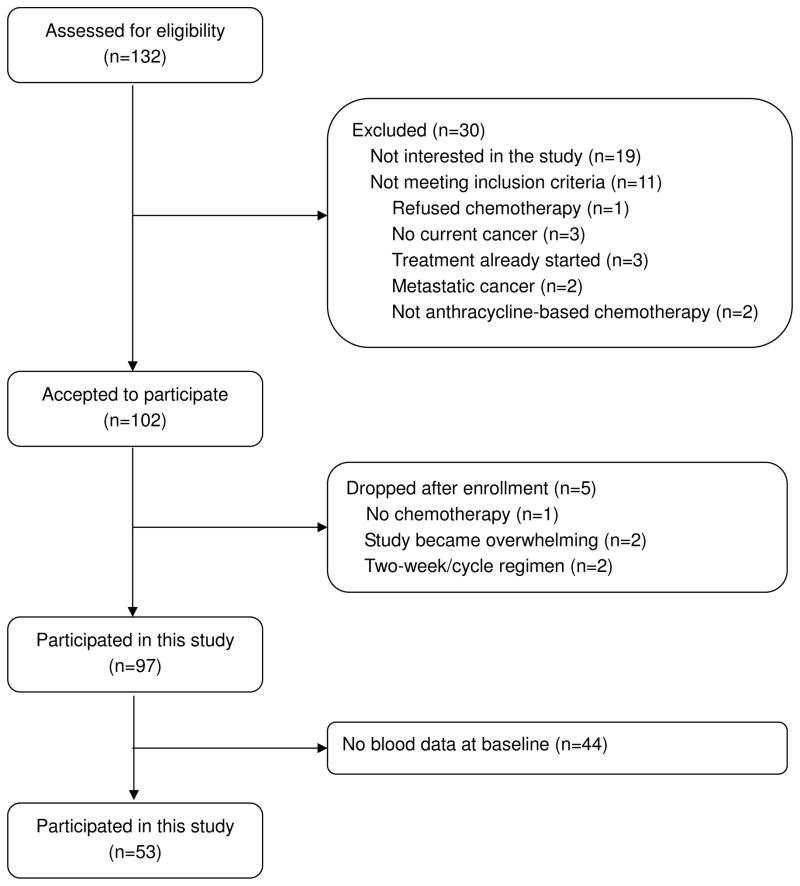

As part of a larger study on sleep and fatigue in cancer, complete data on sleep, fatigue and bloods were available for 53 women (see Figure 1). All women were newly diagnosed with stages I–III breast cancer, had not previously received chemotherapy and were scheduled to receive at least four 3-week cycles of adjuvant or neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Women who were pregnant, with metastatic breast cancer, with confounding underlying medical illnesses, with 2-week cycle chemotherapy regimen, with radiation therapy, with significant pre-existing anemia or with other physical or psychological impairments that would prevent their participation, and all men were excluded. Demographic, disease and treatment characteristics of the 53 patients are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Screening and enrollment flowchart

Table 1.

Demographic, disease and treatment characteristics of the participants (n=53)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 50.3 (9.9) |

| Range | 34 – 79 |

| BMI | |

| Mean (SD) | 27.6 (6.6) |

| Range | 20.6 – 45.3 |

| Race [n (%)] | |

| Caucasian | 39 (73.6) |

| Non-Caucasian | 14 (26.4) |

| Education [n (%)] | |

| Some or completed high school | 13 (24.5) |

| Some college | 14 (26.4) |

| Completed college and above | 26 (49.1) |

| Marital status [n (%)] | |

| Never married | 6 (11.3) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 14 (26.4) |

| Married | 33 (62.3) |

| Household annual income [n (%)] | |

| ≤ $30,000 | 9 (17.0) |

| > $30,000 | 36 (67.9) |

| Refused to answer | 8 (15.1) |

| Menopausal status [n (%)] | |

| Baseline | |

| Pre-menopause | 22 (43.1) |

| Peri-menopause | 3 (5.9) |

| Post-menopause | 18 (35.3) |

| Hysterectomy | 8 (15.7) |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Cycle 4 Week 3 | |

| Pre-menopause | 3 (6.5) |

| Peri-menopause | 5 (10.9) |

| Post-menopause | 31 (67.4) |

| Hysterectomy | 7 (15.2) |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Cancer stage [n (%)] | |

| Stage I | 15 (28.3) |

| Stage II | 26 (49.1) |

| Stage III | 12 (22.6) |

| Surgery [n (%)] | |

| Yes | 41 (77.5) |

| Lumpectomy | 20 (37.7) |

| Mastectomy | 20 (37.7) |

| Double mastectomy | 1 (1.9) |

| No surgery before Chemotherapy | 12 (22.5) |

| Chemotherapy regimen [n (%)] | |

| AC | 13 (24.5) |

| AC + docetaxel | 20 (37.7) |

| AC + paclitaxel | 10 (18.9) |

| AC + fluorouracil | 3 (5.7) |

| ECF | 6 (11.3) |

| Other | 1 (1.9) |

| Sleeping medications [n (%)] | |

| Baseline | |

| yes | 25 (48.1) |

| no | 27 (51.9) |

| not available | 1 |

| Cycle 4 week 3 | |

| yes | 13 (37.1) |

| no | 22 (62.9) |

| not available | 18 |

| Analgesics [n (%)] | |

| Baseline | |

| yes | 34 (65.4) |

| no | 18 (34.6) |

| not available | 1 |

| Cycle 4 week 3 | |

| yes | 8 (22.9) |

| no | 27 (77.1) |

| not available | 18 |

| Antacids [n (%)] | |

| Baseline | |

| yes | 12 (23.1) |

| no | 40 (76.9) |

| not available | 1 |

| Cycle 4 week 3 | |

| yes | 12 (34.3) |

| no | 23 (65.7) |

| not available | 18 |

| Anticonvulsants [n (%)] | |

| Baseline | |

| yes | 4 (7.7) |

| no | 48 (92.3) |

| not available | 1 |

| Cycle 4 week 3 | |

| yes | 3 (8.6) |

| no | 32 (91.4) |

| not available | 18 |

Note: AC = Doxorubicin + Cyclophosphamide, ECF = Epirubicin + Cytoxan + Fluorouracil.

The study was approved by the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Committee on Protection of Human Subjects and by the Rebecca and John Moores UCSD Cancer Center’s Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee.

2.2. Measures

Fatigue

Fatigue was assessed with the 30-item Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF), which has been shown to be a valid and reliable tool for the multidimensional assessment of cancer-related fatigue for both clinical and research applications (Stein et al., 1998; Stein et al., 2004). The items of the MFSI-SF collapse into five subscales of fatigue-dimensions: General, Emotional, Physical, Mental, and Vigor. Each subscale includes 6 items and each item is rated on a 5-point scale indicating how true the statement was during the last week (0=not at all, 4=extremely). Higher scores indicate more severe fatigue, except for the Vigor subscale, where a higher score indicates less fatigue (more Vigor). The sum of General, Physical, Emotional, and Mental subscale scores minus the Vigor subscale score generates a total fatigue score. The range of possible scores for each subscale is 0 to 24, and the range for total fatigue score is −24 to 96.

Sleep

Subjective sleep

Sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989). The PSQI is a 19-item questionnaire which rates patients’ reports of sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication and daytime dysfunction. The total PSQI scores range from 0–21 with high scores reflecting poor sleep quality. A total score above 5 is generally considered poor sleep.

Objective sleep

Objective sleep was measured with the Actillume actigraph (Ambulatory Monitoring Inc, Ardsley, New York). The Actillume is a small device approximately 1x3x6cm in size, which contains a piezoelectric linear accelerometer (sensitive to 0.003 g and above), a log-linear photometric transducer (sensitive from <0.01 lux to >100,000 lux), a microprocessor, 32K RAM memory, and associated circuitry. Data were collected in 1-minute epochs and were downloaded onto a desktop computer. All data were hand-edited with additional information from a sleep log completed by the participant where they recorded time to bed, time up in the morning and other information needed for editing the actigraphy data. The Action-4 software package for Actillume was used to score sleep and wake at night and during the day.

Actigraphy has been validated and shown to be reliable in recording of sleep and wake in multiple studies (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2003). Total sleep time (TST), total wake time from time to bed to final awakening in the morning (TWT), total nap time (NAPTIME) were calculated. Daytime sleep, or naps, was defined as any 10 or more minutes of consecutive actigraphic inactivity (sleep) during hours between final up-time and bedtime.

Inflammatory markers

Blood samples were collected in either EDTA or sodium citrate, kept on ice at 4°C until centrifugation, and then stored at −80°C until assay. The following inflammatory markers were assayed by commercial ELISA: IL-6, IL-1RA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and CRP (high sensitivity Denka Seiken assay). Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <5% and <10%, respectively. All samples from a particular patient were assayed together by a technician who was blinded to patient and treatment conditions. The lower limit of detection (LLD) for IL-6, IL-1RA or CRP was 0.016 pg/ml, 14 pg/ml, or 0.05 mg/l, respectively, and none of the patients’ values were below the LLD.

2.3. Procedure

Detailed procedural information can be found in Liu et al (Liu et al., 2005). Briefly, after consent forms were signed, medical records were abstracted for medical history and current medication use, and data were collected before (baseline) and during cycles 1 and 4 of chemotherapy.

Baseline questionnaires were collected during the week before the start of chemotherapy. Baseline blood was collected at the Moores UCSD Cancer Center on the morning before the first chemotherapy administration. Questionnaires were administered and blood was drawn again during the last two weeks of each cycle (C1W2, C1W3, C4W2 and C4W3). Fifty-three patients had blood sampled at baseline, and this study was based on the data from these 53 women.

Questionnaire data from the same time points were included in this analysis. Data of menopause status and utilization of medications other than chemotherapy were only collected during baseline and at C4W3. The menopause status was defined according to the STRAW criteria (Soules et al., 2001): pre-menopause, peri-menopause and post-menopause; one extra group (hysterectomy) was also included as a type of menopausal status due to this particular study sample.

2.4. Data analysis

Values of inflammatory markers were logarithmically transformed due to their non-Gaussian distributions. A mixed model analysis (Diggle et al., 1994) was used to test the significance of possible confounding factors, to examine changes in fatigue, sleep and inflammatory markers over the course of chemotherapy, and to examine the longitudinal relationship between fatigue and sleep and inflammatory markers. This modeling approach accounts for correlations in repeated measures within a subject and also allows for partially missing data (i.e., subjects with missing data at some but not all time-points can be included in the model). A random intercept was included in each mixed model to account for subject-specific effects.

In order to identify potential confounding factors, the following mixed models were developed: inflammatory markers were the dependent variables and demographic, disease or treatment characteristics were the independent variables. Variables with p<0.1 were determined to be confounders, and were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

The changes in fatigue, sleep or inflammatory markers over time were examined with mixed models separately. In these mixed models, fatigue, sleep or inflammatory markers were independent variables, chemotherapy week (time) was modeled as a fixed effect and confounding factors were controlled in each model.

The last set of mixed models examined the longitudinal relationships between changes in fatigue and sleep from baseline to each treatment time point and changes in inflammatory markers from baseline to treatment. Due to the multiple markers and hypothesis tests under consideration, we applied Fisher’s Least Significant Difference paradigm to control for Type I error (Miller, 1981) and performed an omnibus test using a composite marker index which was calculated as follows: first, a Z-score for each inflammatory marker was calculated (Z-score = (given marker level – baseline mean of the marker)/standard deviation of the marker over time), then the mean of all markers’ Z-scores constituted a composite index for each patient at each time point. A mixed model was fit with this composite marker index as the main effect, and fatigue and sleep as the response variable, and time modeled as a fixed effect. The t-statistic and corresponding p-value of the composite index were examined for each of these mixed models, to test the omnibus null hypothesis that the composite index was not associated with sleep/fatigue outcomes.

The t-statistic and p-value for the composite index were t=2.21 (p=0.03) for sleep and t=1.69 (p=0.09) for fatigue. The null hypothesis was rejected when a liberal p<0.1 was used for the omnibus test, as few studies have the data to examine inflammation and sleep/fatigue in a breast cancer cohort undergoing chemotherapy. These results will of course need to be replicated in larger studies. Rejection of the omnibus null prompted further exploratory analyses to explicitly examine associations between each biomarker and outcomes.

In the last set of mixed models, fatigue or sleep was the dependent variable and each of the inflammatory markers was the independent variable, with the inflammatory marker included as a random effect, thereby allowing for subject-specific slope terms for inflammatory markers in the model. These mixed models were adjusted with chemotherapy week (time) and confounding demographic, disease and treatment characteristic variables accordingly. Adjusted regression coefficients (β-value) with standard errors and associated p-values are presented.

All analyses were performed using version 9.2 of SAS (SAS Institute Inc. 2008).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and disease characteristics

As summarized in Table 1, the mean age of the 53 women was 50.3 years, 74% were Caucasian, 62% were married, 75% had at least some college education, 68% reported an annual income of more than $30,000, 62% had a BMI greater than 25 and 25% had a BMI greater than 30. Eighty-three percent of the women were treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide [AC], AC plus docetaxel, AC plus paclitaxel, or AC plus fluorouracil, the rest were either treated with cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and fluorouracil [CEF]), or their therapy was indicated as ‘other’ regimen.

3.2. Confounders of fatigue, sleep and inflammatory markers

The following variables in Table 1 were tested as potential confounders in relation to fatigue, sleep quality, or inflammatory markers: age, BMI, race, education, income, marital status, menopause status, use of different medications, cancer stage, adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment, chemotherapy regimen and surgery. In addition to their chemotherapy, women also used other medications to treat other symptoms, such as analgesics, antacids, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, stimulants, sedating medications, etc. Sedating medications, including antihistamines, major tranquilizers, minor tranquilizers, OTC hypnotics and sedative hypnotics were considered as sleeping medications. The use of these medications was also tested as a potential confounder.

At the p<0.1 level, confounders for higher total MFSI-SF scores were being non-Caucasian (p=0.04) and use of antacids (p=0.06); confounders for higher total PSQI scores were use of sleep medications (p=0.006), being non-Caucasian (p=0.01) and having surgery (p=0.02); confounders for shorter TST were higher BMI (p=0.01), use of analgesics (p=0.07) and being non-Caucasian (p=0.09); confounders for longer TWT were higher BMI (p=0.02) and being non-Caucasian (p=0.03); no confounders were identified for NAPTIME. The confounder for higher IL-6 levels was lower income (p=0.007); confounders for higher IL-1RA levels were not using analgesics (p=0.01), older age (p=0.02), higher BMI (p=0.04) and use of anticonvulsants (p=0.06); confounders for higher CRP levels were higher BMI (p=0.01) and lower income (p=0.02). BMI was only correlated with TST, TWT, IL-1RA and CRP at the p<0.1 level, thus was adjusted only in those related models. The medication confounders, i.e., sleeping medications, analgesics, antacids and anticonvulsants are listed in Table 1.

3.3. Changes in fatigue over time

As seen in Table 2, there was a significant overall time effect for total MFSI-SF scores (p<0.0001). Compared to baseline, total MFSI-SF scores significantly increased at all four time points (all p’s<0.05).

Table 2.

Fatigue and subjective and objective sleep before and during chemotherapy [mean(SD), n=53]

| Fatigue and Sleep Parameters | Baseline | C1W2 | C1W3 | C4W2 | C4W3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total MFSI-SF score a† | 6.8 (18.3) | 10.6 (21.7) * | 10.5 (21.4) * | 17.5 (24.9) ** | 15.1 (22.2) ** |

| Subjective Sleep | |||||

| Total PSQI score b | 7.1 (3.6) | 7.9 (3.9) | 7.3 (3.9) | 7.8 (4.1) | 7.4 (3.8) |

| Objective Sleep | |||||

| Total sleep time (hours) c | 6.32 (1.38) | 6.25 (1.53) | 6.33 (1.52) | 6.50 (1.46) | 6.60 (1.51) |

| Nighttime total wake time (hours) d | 2.18 (1.28) | 2.20 (1.29) | 2.20 (1.16) | 2.22 (1.16) | 2.34 (1.35) |

| Total nap time (hours) | 1.10 (1.15) | 1.13 (1.35) | 1.22 (1.35) | 1.40 (1.35) * | 1.45 (1.32) |

Note: Overall time effect:

p<0.003; compared to baseline:

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

adjusted for race and use of antacids;

adjusted for race, use of sleep medications and having surgery;

adjusted for age, BMI, race and use of analgesics;

adjusted for age, BMI and race. MFSI-SF = Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form, higher score indicates more fatigue. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, higher score indicates poorer sleep quality. C1W2 = Cycle 1 Week 2, C1W3 = Cycle 1 Week 3; C4W2 = Cycle 4 Week 2, C4W3 = Cycle 4 Week 3.

3.4. Changes in subjective and objective sleep over time

Subjective sleep

As also seen in Table 2, there was no overall time effect for total PSQI scores (p>0.6), and no significant changes in total PSQI scores from baseline to any of the four treatment time points (all p’s>0.1). However, the mean total PSQI scores were all above 5 at all time points. These results indicate that women were already experiencing poor sleep quality before treatment and continued to report poor sleep quality during treatment.

Objective sleep

There were no overall time effects for TST, TWT or NAPTIME (all p’s>0.1). There were also no significant changes in TST and TWT from baseline to treatment (all p’s>0.09). However, NAPTIME increased from baseline to C4W2 (p<0.05). Although there were no overall time effects for TST, TWT and NAPTIME, the mean TSTs were all less than 7 hours, the mean TWTs were all greater than 2 hours, and the mean NAPTIMEs were all longer than 1 hour, suggesting insufficient sleep at night and daytime sleepiness.

3.5. Changes in inflammatory markers over time

There were significant overall time effects for levels of IL-6 and IL-1RA (both p’s<0.003). As seen in Table 3, compared to baseline, IL-6 increased significantly at C4W2 (p=0.0003) and C4W3 (p=0.04), while IL-1RA dropped significantly at C1W3 (p<0.0001). There no significant changes of CRP levels during treatment (p=0.2).

Table 3.

Inflammatory markers before and during chemotherapy [mean(SD), n=53]

| Inflammatory Markers | Baseline | C1W2 | C1W3 | C4W2 | C4W3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (pg/ml) a† | 2.93 (3.99) | 2.67 (1.78) | 3.09 (2.58) | 4.21 (3.12) ** | 3.37 (3.33) * |

| IL-1RA (pg/ml) b† | 1390.55 (1435.65) | 973.95 (1162.42) | 447.19 (696.50) ** | 949.46 (1313.49) | 1015.45 (1278.11) |

| CRP (mg/l) c | 3.09 (2.82) | 1.54 (1.56) | 3.61 (5.33) | 4.76 (5.63) | 3.24 (2.98) |

Note: Overall time effect:

p<0.003; compared to baseline:

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

adjusted for income;

adjusted for age, BMI, use of analgesics and anticonvulsants;

adjusted for BMI and income. IL-6 = Interleukin-6; IL-1RA = Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; CRP = C-reactive protein. C1W2 = Cycle 1 Week 2, C1W3 = Cycle 1 Week 3; C4W2 = Cycle 4 Week 2, C4W3 = Cycle 4 Week 3.

3.6. Associations between changes in fatigue and sleep and changes in inflammatory markers

As shown in Table 4, mixed model results revealed that changes in total MFSI-SF scores were positively associated with changes in circulating levels of IL-6. Every increase of 1 pg/ml IL-6 was associated with an increase of 14 points of total MFSI-SF score. Changes in total PSQI scores were positively associated with changes in levels of IL-6 and IL-1RA. Every increase of 1 pg/ml IL-6 was associated with an increase of 1.7 points of total PSQI score, and every increase of 1.0 pg/ml IL-1RA was associated with an increase of 1.0 point of total PSQI score. Changes in TWT were positively associated with changes in CRP levels; every increase of 1 mg/l CRP was associated with an increase of 46 minutes of total wake time during the night.

Table 4.

Mixed model results with parameters of fatigue or sleep as dependent variable and inflammatory markers as independent variable

| Fatigue and sleep parameters | Inflammatory markers | Mixed model results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. β-value | Standard Error | p-value | ||

| Total MFSI-SF score a | IL-6 | 14.027 | 4.194 | 0.002 |

| IL-1RA | −2.320 | 2.111 | 0.3 | |

| CRP | 5.124 | 4.703 | 0.3 | |

| Total PSQI score b | IL-6 | 1.740 | 0.690 | 0.02 |

| IL-1RA | 0.974 | 0.423 | 0.03 | |

| CRP | 0.997 | 0.828 | 0. 2 | |

| Total nighttime sleep time (TST) c | IL-6 | −0.134 | 0.307 | 0.7 |

| IL-1RA | 0.149 | 0.191 | 0.4 | |

| CRP | −0.100 | 0.403 | 0.8 | |

| Total nighttime wake time (TWT) d | IL-6 | −0.180 | 0.209 | 0.6 |

| IL-1RA | 0.190 | 0.163 | 0.2 | |

| CRP | 0.774 | 0.261 | 0.01 | |

| Total nap time (NAPTIME) | IL-6 | 0.365 | 0.260 | 0.2 |

| IL-1RA | −0.129 | 0.140 | 0.4 | |

| CRP | 0.337 | 0.400 | 0.4 | |

Note:

adjusted for time, race and use of antacids;

adjusted for time, race and use of sleeping medications;

adjusted for age, race and use of analgesics;

adjusted for age, BMI and race. Bold p-values indicate significant associations between fatigue or sleep and inflammatory markers. MFSI-SF = Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form, higher score indicates more fatigue. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, higher score indicates poorer sleep quality. IL-6 = Interleukin-6; IL-1RA = Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; CRP = C-reactive protein.

Since fatigue was significantly associated with both subjectively reported and objectively measured sleep (Liu et al., 2012), in order to test if the association between sleep and inflammation was driven by fatigue, or the association between fatigue and inflammation was driven by sleep, the above mixed models were repeated with controlling for total MFSI-SF scores in both subjective and objective sleep-related models, and controlling for total PSQI scores in fatigue-related models. Results show that except the disappearance of the significant relationship between PSQI and IL-6 (p=0.3 instead of p=0.02), other significant relationships between PSQI and IL-1RA (p=0.009 instead of p=0.03), between TWT and CRP (p=0.008 instead of p=0.01), and between MFSI-SF and IL-6 (p=0.008 instead of p=0.002) still remained, suggesting that except the relationship between subjective sleep and IL-6, the majority relationships between sleep and inflammation were not driven by fatigue, or vice versa.

There were no significant associations between changes in fatigue or sleep quality and changes in CRP, or between TST and NAPTIME and any of the inflammatory markers as determined by the mixed models, even after controlling fatigue for sleep or controlling sleep for fatigue.

4. Discussion

This longitudinal study evaluated the relationship between fatigue and sleep parameters and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. The results showed that during chemotherapy, fatigue was worse than pre-chemotherapy while sleep quality remained poor both before and during chemotherapy. Changes in fatigue and reports of sleep quality were significantly associated with changes of circulating levels of IL-6, and this relationship between sleep quality and IL-6 was likely driven by fatigue. Changes in reports of sleep quality were also significantly associated with changes of circulating levels of IL-1RA. The only objective measure of sleep associated with a biomarker was changes in total wake time at night, which was associated with changes in CRP. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report a longitudinal relationship between both fatigue and sleep parameters and inflammation in breast cancer patients.

As previously reported (Liu et al., 2012), these women experienced more cancer-related fatigue during chemotherapy than during baseline, while their self-reported sleep quality remained poor both before and during treatment. Along with increased fatigue and poor sleep quality during chemotherapy, circulating levels of IL-6 increased during cycle 4 of treatment, and this increase was correlated with more fatigue and poor sleep. Previous studies have shown that IL-6 is not only associated with the risk of breast cancer (Slattery et al., 2007), but is also associated with cancer stage (Ravishankaran and Karunanithi, 2011), and worse prognosis (Knupfer and Preiss, 2007). The significant relationships between changes in both fatigue and subjective sleep quality and changes in IL-6 found in this study add new evidence to the important role of IL-6 in breast cancer. In support of the relationship between fatigue and inflammation, a relationship between elevated VEGF and sICAM-1 and more fatigue was previously reported from a smaller sample from the same study (N=29), although that relationship was based on data obtained at only two time points (Mills et al., 2005). This current study also confirmed that changes in IL-6 were associated with changes in reports of sleep quality, as was suggested in patients with lung cancer (Wang et al., 2010), although the relationship found in this study was likely driven by fatigue.

There have been conflicting reports on the role of IL-1RA in cancer. Some researchers believe that IL-1RA can block IL-1 induced inflammation and disease, while others believe that IL-1RA enhances the malignant growth (Miller et al., 2000). In addition, chemotherapy and exercise have been reported to decrease levels of IL-1RA in cancer patients (Allgayer et al., 2004; Denecker et al., 1997; Haku et al., 1996). Our results show an overall decrease of circulating levels of IL-1RA which were associated with improved sleep quality (lower scores on the PSQI, although scores were still above 5 in the poor sleep quality range). These data suggest that IL-1RA may also play an important but complex role in cancer and cancer patients’ sleep.

An interesting finding of our study was the significant relationship between changes in total wake time during the night and changes in CRP; however no other significant relationships between biomarkers and nighttime or daytime objective sleep measures were seen. The mean time spent awake at night at all five time points was longer than 2 hours, and the mean total sleep time at all five time points was less than 7 hours. Too much time spent awake and not enough time spent asleep are signs of insufficient sleep, which may be a result of the cancer itself or of the cancer treatment. Insufficient nighttime sleep also results in daytime sleepiness and this was confirmed by the longer time spent napping (>1 hour at all five time points) in this study. In other words, the women might have been trying to compensate for their sleep loss at night by napping during the day. In a study of young adults, a reduction of sleep from 8 hours to 6 hours per night for one week resulted in elevated cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (Vgontzas et al., 2004). In another study among healthy adults, one night’s partial sleep deprivation (awake from 11 pm to 3 am) induced increases in transcription of IL-6 and TNF-α messenger RNA, as well as increases in monocyte production of IL-6 and TNF-α (Irwin et al., 2006). On the other hand, chronic IFN-α administration in patients with hepatitis C led to increases in total wake time after sleep onset and decreases in slow wake (deep) sleep (Raison et al., 2010). Findings from the above studies, together with the relationship between wake time at night and CRP found in the current study, may reflect the effect of sleep restriction on inflammatory markers, and therefore be a sign of the bi-directorial relationship between sleep and inflammation, as suggested by Vgontzas and colleagues (Vgontzas et al., 1997; Vgontzas et al., 2004). Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

The significant association between inflammatory markers and cancer-related symptoms suggest that fatigue and sleep disturbance may possibly be mediated by some inflammatory markers (Kurzrock, 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008; Opp, 2005). In cancer patients, the disrupted balance between endogenous inflammatory marker levels, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α, and their antagonists may contribute to cancer related symptoms, such as anemia, fever, pain, weight loss, infection, etc., and these symptoms exacerbate cancer-related fatigue (Kurzrock, 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008). At the same time, inflammatory markers may directly cause fatigue (Bower et al,. 2011; Kurzrock, 2001). Studies suggest that IL-1, IL-6 and THF-α may also act as sleep regulators/modulators, they could increase NREM sleep and change sleep/wake behavior in both animals and humans (Opp, 2005). Thus, increased levels of cytokines may cause alterations of sleep patterns in cancer patients, and this disturbed sleep might also be a cause of, and/or caused by fatigue (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2001; Roscoe et al., 2007). This hypothesis has been supported by a recently published study (Wang et al., 2010), as well as by our data in this study.

The associations between fatigue and sleep and inflammatory markers have also gained support from recent published genetic studies (Aouizerat et al., 2009; Collado-Hidalgo et al., 2006; Collado-Hidalgo et al., 2008; Miaskowski et al., 2010). Collado-Hidalgo and colleagues (Collado-Hidalgo et al., 2008) found that genetic polymorphisms in IL-1 are associated with persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. In addition, Miaskowski and colleagues found a genetic association between a functional promoter polymorphism in the IL-6 and TNF-α genes and severity of fatigue and sleep disturbances among patients with different types of cancer undergoing radiation therapy (Aouizerat et al., 2009; Miaskowski et al., 2010).

A relationship between fatigue and sleep has been previously reported in cancer patients (Roscoe et al., 2007; Zee and Ancoli-Israel, 2009). We also previously showed that fatigue was present before chemotherapy (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2006), worsened during treatment (Liu et al., 2005), and was significantly correlated with both subjective and objective measures of sleep (Liu et al., 2012). This study further revealed that fatigue and sleep were associated with particular common inflammatory markers, such as IL-6, suggesting fatigue and poor sleep quality may share some common etiology, such as inflammation in cancer patients.

This study had certain limitations. Data before surgery were not collected, so it is not clear if relationships between sleep and fatigue and inflammatory markers would be present before surgery or if surgery impacted these relationships. There were also no follow-up data after the end of chemotherapy, so the long-term relationships beyond treatment between sleep and fatigue and inflammatory markers could not be examined in this study. Data were obtained from women with breast cancer, and from women with relatively higher education levels and higher household annual incomes, so conclusions cannot be extended to men, to patients with different socioeconomic status, or to patients with different cancers. The time between surgery and the start of chemotherapy, evaluation of vasovagal symptoms, as well as the use of anti-inflammatories such as statins, were not collected in this study, and they all could have potentially affected the levels of inflammatory markers.

In conclusion, the current study found that increased fatigue, poor sleep quality and increased wake time at night were associated with changes in inflammatory markers over the course of chemotherapy. These results suggest that both fatigue and sleep may share common underlying biochemical etiology. Further clinical and basic studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NCI CA112035, UL1RR031980, NIH M01 RR00827, the UCSD Stein Institute for Research on Aging and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health (CESAMH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Sonia Ancoli-Israel has been a consultant to Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, NeuroVigil, Inc., Philips, Somaxon. All other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allgayer H, Nicolaus S, Schreiber S. Decreased interleukin-1 receptor antagonist response following moderate exercise in patients with colorectal carcinoma after primary treatment. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi CA, Chambers M, Moorcroft WH, Pollak C. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Liu L, Marler M, Parker BA, Jones V, Robins Sadler G, Dimsdale JE, Cohen-Zion M, Fiorentino L. Fatigue, sleep and circadian rhythms prior to chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:201–209. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0861-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Moore P, Jones V. The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: A review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aouizerat BE, Dodd M, Lee K, West C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Wara W, Swift P, Dunn LB, Miaskowski C. Preliminary evidence of a genetic association between tumor necrosis factor alpha and the severity of sleep disturbance and morning fatigue. Biol Res Nurs. 2009;11:27–41. doi: 10.1177/1099800409333871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S. Breast Cancer and Fatigue. Sleep Med Clin. 2008;3:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AM, Parker KP, Young-McCaughan S, Mallory GA, Barsevick AM, Beck SL, Carpenter JS, Carter PA, Farr LA, Hinds PS, Lee KA, Miaskowski C, Mock V, Payne JK, Hall M. Sleep wake disturbances in people with cancer and their caregivers: state of the science. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:E98–126. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.E98-E126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE, Ganz P, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:604–611. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE, Ganz P, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3517–3522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CFI, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2759–2766. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Cole SW. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: early findings. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1197–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecker NE, Kullberg BJ, Drenth JP, Raemaekers JM, van der Meer JW. Regulation of the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and antagonists during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in patients with haematological malignancies. Cytokine. 1997;9:702–710. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haku T, Yanagawa H, Ohmoto Y, Takeuchi E, Yano S, Hanibuchi M, Nokihara H, Nishimura N, Sone S. Systemic chemotherapy alters interleukin-1 beta and its receptor antagonist production by human alveolar macrophages in lung cancer patients. Oncol Res. 1996;8:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, Collado-Hidalgo A, Cole S. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1756–1762. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Bluthe R-M, Dantzer R, Zhou J-H, Shen W-H, Johnson RW, Broussard SR. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knupfer H, Preiss R. Significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in breast cancer (review) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzrock R. The role of cytokines in cancer-related fatigue. Cancer. 2001;92:1684–1688. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1684::aid-cncr1497>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BN, Dantzer R, Langley KE, Bennett GJ, Dougherty PM, Dunn AJ, Meyers CA, Miller AH, Payne R, Reuben JM, Wang XS, Cleeland CS. A cytokine-based neuroimmunologic mechanism of cancer-related symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2004;11:279–292. doi: 10.1159/000079408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disturbances in cancer. Psychiatry Annals. 2008;38:627–634. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20080901-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Marler M, Parker BA, Jones V, Johnson S, Cohen-Zion M, Fiorentino L, Sadler GR, Ancoli-Israel S. The relationship between fatigue and light exposure during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:1010–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Rissling M, Natajaran L, Fiorentino L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Sadler GR, Parker BA, Ancoli-Israel S. The Longitudinal Relationship between Fatigue and Sleep in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Sleep. 2012;35:237–245. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K, West C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Wara W, Swift PS, Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE. Preliminary evidence of an association between a functional interleukin-6 polymorphism and fatigue and sleep disturbance in oncology patients and their family caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Ancoli-Israel S, Bower JE, Capuron L, Irwin MR. Neuroendocrine-immune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:971–982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ, Kurtzman SH, Anderson K, Wang Y, Stankus M, Renna M, Lindquist R, Barrows G, Kreutzer DL. Interleukin-1 family expression in human breast cancer: interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Cancer Invest. 2000;18:293–302. doi: 10.3109/07357900009012171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RG. Simultaneous Statistical Inference, Springer Series in Statistics. 2. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Parker BA, Natarajan L, Hong S, Jain S, Sadler GR, von Kanel R. Predictors of Inflammation in Response to Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Parker BA, Dimsdale JE, Sadler GR, Ancoli-Israel S. The relationship between fatigue, quality of life and inflammation during anthracycline-based chemotherapy In breast cancer. Biol Psychol. 2005;69:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Parker BA, Jones V, Adler KA, Perez CJ, Johnson S, Cohen-Zion M, Marler MR, Sadler GR, Dimsdale JE, Ancoli-Israel S. The effects of standard anthracycline-based chemotherapy on soluble icam-1 and VEFG levels in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4998–5003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0734-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon DM, Fitzsimons H, Lynch J, Tormey S, Malone C, Given HF. Soluble adhesion molecules (E_selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) in breast carcinoma. Euro J Cancer. 2002;38:2252–2257. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opp MR. Cytokines and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, Rye DB, Woolwine BJ, Vogt GJ, Bautista BM, Spivey JR, Miller AH. Chronic interferon-alpha administration disrupts sleep continuity and depth in patients with hepatitis C: association with fatigue, motor slowing, and increased evening cortisol. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:942–949. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankaran P, Karunanithi R. Clinical significance of preoperative serum interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein level in breast cancer patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich T, Innominato PF, Boerner J, Iacobelli S, Baron B, Jasmin C, Levi F. Elevated serum cytokines correlated with altered behavior, serum cortisol rhythm, and dampened 24-hour rest-activity patterns in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1757–1764. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Kaufman ME, Matteson-Rusby SE, Palesh OG, Ryan JL, Kohli S, Perlis ML, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep disorders. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):35–42. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C, Hong S, Natarajan L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The association between fatigue and inflammatory marker levels in cancer patients: a quantitative review. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:413–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery ML, Curtin K, Baumgartner R, Sweeney C, Byers T, Giuliano AR, Baumgartner KB, Wolff RR. IL6, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and breast cancer risk in women living in the southwestern United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:747–755. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods N. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Park City, Utah, July, 2001. Menopause. 2001;8:402–407. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KD, Jacobsen PB, Blanchard CM, Thors C. Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KD, Martin SC, Hann DM, Jacobsen PB. A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:143–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Kales A, Tyson K, Chrousos G. Elevation of plasma cytokines in disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness: role of sleep disturbance and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol & Metab. 1997;82:1313–1316. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Bixler EO, Lin HM, Follett H, Kales A, Chrousos GP. Adverse effects of modest sleep restriction on sleepiness, performance, and inflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2119–2126. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, Mao L, Cleeland CS, Komaki RR, Mobley GM, Liao Z. Inflammatory cytokines are associated with the development of symptom burden in patients with NSCLC undergoing concurrent chemoradiation therapy. Brain Behav & Immunity. 2010;24:968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zee PC, Ancoli-Israel S. Does effective management of sleep disorders reduce cancer-related fatigue? Drugs. 2009;69:29–41. doi: 10.2165/11531140-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]