Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the prevalence and correlates of comorbid anxiety disorders among individuals with bipolar disorders (BP) and their association with prospectively ascertained comorbidities, treatment, and psychosocial functioning.

METHOD

As part of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 1600 adults who met lifetime DSM-IV criteria for BP-I (n=1172) and BP-II (n=428) were included. Individuals were evaluated using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DMS-IV Version and data was analyzed from Waves 1 and 2, approximately 3 years apart.

RESULTS

Sixty percent of individuals with BP had at least one lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder. Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders shared lifetime risk factors for major depressive disorder and had prospectively more depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and more treatment seeking than those without anxiety. During the follow-up, higher incidence of panic disorder, drug use disorders, and lower psychosocial functioning were found in individuals with BP with versus without anxiety disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

Anxiety disorders are prospectively associated with elevated BP severity and BP-related mental health service use. Early identification and treatment of anxiety disorders are warranted to improve the course and outcome of individuals with BP.

Keywords: anxiety, bipolar disorder, outcome, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

Clinical (Boylan et al., 2004; Henry et al., 2003; McElroy et al., 2001; Perlis et al., 2004; Pini et al., 1997) and epidemiological studies (Chen & Dilsaver, 1995a; b; Goodwin & Hoven, 2002; Kessler, Rubinow, Holmes, Abelson, & Zhao, 1997; Merikangas et al., 2007) have documented high rates of anxiety disorders among adults with bipolar disorder (BP) and provided compelling evidence that anxiety disorders may be the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidity among patients with BP, particularly BP-II (Cassano, Pini, Saettoni, & Dell'Osso, 1999; Doughty, Wells, Joyce, Olds, & Walsh, 2004; Henry et al., 2003; Perugi et al., 1999; Pini et al., 1997). For example, the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) (Perlis et al., 2004) found that 51% of 983 adults with BP had at least one comorbid lifetime anxiety disorder. Although a high prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders is not unique to BP, some studies have shown that comorbid anxiety disorders are even more common in BP than in major depressive disorder (MDD) (Chen et al., 1995a; Simon et al., 2003).

Recent studies have suggested that comorbid anxiety disorders are associated with worse course and outcome of individuals with BP (Boylan et al., 2004; Coryell et al., 2009; Gaudiano & Miller, 2005; Otto et al., 2006). Regarding clinical characteristics of BP with anxiety disorders, the literature suggests earlier onset of mood symptoms, greater severity of BP symptoms, increased prevalence of suicidal behavior, longer time to remission from affective episodes, and reduced duration of time spent euthymic (Boylan et al., 2004; MacQueen et al., 2003; Otto et al., 2006; Simon et al., 2004). Comorbid anxiety disorders among individuals with BP are also associated with greater prevalence of drug and alcohol use disorders (Goodwin et al., 2002; MacQueen et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2004). Studies focusing on the treatment of individuals with BP have shown that comorbid anxiety is associated with worse response to mood-stabilizing medications, greater risk of medication-induced mania, and increased psychiatric polypharmacy (Feske et al., 2000; Henry et al., 2003; Pini et al., 2003). In addition, poor functional outcome and diminished quality of life (Albert, Rosso, Maina, & Bogetto, 2008; Bauer et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2004) have been related with comorbid anxiety in individuals with BP.

The majority of the above findings are derived from clinical samples, and epidemiologic studies are therefore needed to examine whether those findings extend to the general population of individuals with BP. Several epidemiologic studies confirm that comorbid anxiety disorders are exceedingly prevalent in BP (Angst, 1998; Chen et al., 1995a; b; Goodwin et al., 2002; Merikangas et al., 2007; Merikangas et al., 2011). However, to our knowledge, epidemiologic surveys have not examined the course and outcome of individuals with BP and anxiety disorders.

Previously reported cross-sectional data from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) suggested that comorbid anxiety disorders confer increased liability toward poor mental health functioning and greater BP-related health service utilization (Goldstein & Levitt, 2008). Given the clinical relevance of anxiety and BP and the lack of longitudinal epidemiologic studies, we sought to assess prospectively for the first time the course and outcome of individuals with BP with versus without comorbid anxiety disorders in a large, nationally representative epidemiologic study, the NESARC.

The aim of this study was to examine the prevalence and correlates of comorbid anxiety disorders among individuals with BP and their association with prospectively ascertained comorbidities, treatment, and psychosocial functioning. We hypothesized that as compared with individuals with BP and no comorbid anxiety disorders, those with BP and a comorbid anxiety disorder would have: (1) more severe lifetime BP symptoms, (2) greater proportion of new onset of comorbidities, (3) higher rates of treatment seeking, and (4) lower psychosocial functioning.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The NESARC (Grant, Kaplan, Moore, & Kimball, 2005a; Grant, Kaplan, Shepard, & Moore, 2003b) is a longitudinal nationally representative survey based on the civilian, non-institutionalized population of the 50 United States, age 18 and over. Data collection was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and was conducted in two waves using face-to-face interviews. Wave 1 interviews (n = 43,093) were conducted between 2001 and 2002 by trained lay-interviewers who had an average of five years experience working on census and other health-related national surveys (Grant et al., 2003b). The current study utilized data from Wave 1 as well as Wave 2 interviews, which were conducted between 2004 and 2005 with 34,653 of the NESARC Wave 2 respondents (Grant et al., 2005a). After accounting for those ineligible for the Wave 2 interview, the response rate for Wave 2 was 86.7%. The mean interval between Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews was 36.6 (SD=2.62) months. The research protocol, including informed consent procedures, received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before beginning the interviews. Detailed descriptions of methodology, sampling, and weighting procedures can be found elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003b).

Respondents with lifetime diagnosis of BP-I (n=1172) and BP-II (n=428) in Wave 1 were included in the present study, and were divided into two groups for the purpose of analyses: individuals with lifetime BP and anxiety disorders (2.09%; n=725) and individuals with BP without anxiety disorders (2.38%; n=875).

Measures

Sociodemographic measures included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status and personal income.

All diagnoses were made according to DSM-IV criteria using the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-Version for DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV), a valid, reliable, fully structured diagnostic interview designed for use by professional interviewers who are not clinicians (Grant, Dawson, & Hasin, 2001). The AUDADIS-IV diagnoses of mood and anxiety disorders (Grant et al., 2005c) and substance use disorders (Grant et al., 2004) have demonstrated reliability and validity. Reliability of the BP-I diagnosis (κ=0.59) is fair and good for BP-II (κ=0.69) (Grant et al., 2005b), whereas the reliability is excellent for alcohol diagnoses (κ≥0.74) and drug diagnoses (κ≥0.79) (Grant et al., 2004). The anxiety disorders included in the present study are social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, which have fair to good reliability (κ=0.42–0.52) (Grant et al., 2004).

The study further included variables considered risk factors for BP in individuals with versus without anxiety disorders that have been extensively studied in major depressive disorder (MDD) (Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 2002; 2006), dysthymic disorder (Blanco et al., 2010), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (Vesga-Lopez et al., 2008). For consistency with previous research, we queried about lifetime risk factors for depression initially proposed by Kendler and colleagues (Kendler et al., 2002; 2006), but which may increase the risk for anxiety disorders as well (Vesga-Lopez et al., 2008). In accordance with previous research (Vesga-Lopez et al., 2008) we organized the risk factors into 3 sets: (1) familial influences, including family history of depression, drug and alcohol use disorders; (2) risk factors with childhood onset, including parental loss before age 18, vulnerable family environment (defined as history of separation from a biologic parent before age 18), early onset of anxiety disorder (viz, before age 18), conduct disorder and low self-esteem (defined as present most of the time throughout their lives); and, (3) risk factors manifested into adulthood, including history of separation or divorce, low emotional reactivity, and social support.

We examined the clinical characteristics of BP (e.g., number and length of depressive and mania or hypomania episodes, recovery from depression and mania, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) between Wave 1 and Wave 2 for individuals with BP with versus without anxiety disorders. In addition, we examined the treatment of BP (sought counseling, medication, any other treatment, hospitalized and attended to the emergency room) for major depressive (MDE) and mania or hypomania episodes between Wave 1 and Wave 2 for individuals with BP with versus without anxiety disorder. Incidence of comorbidities (alcohol or drug abuse/dependence, nicotine dependence, panic disorder, SAD, and/or GAD) was defined as developing a new disorder between Wave 1 and Wave 2.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed in both waves with the mental component summary of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (SF-12), a reliable and valid measure of disability used in population surveys (Ware, Kosinski, Turner-Bowker, & Gandek, 2005). We also examined the 14 items of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (e.g., move or anyone new living with, fired from job, unemployment, trouble or change work) (Holmes & Rahe, 1967) in the 12 month preceding Wave 2.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SUDAAN to adjust for the complex design of the NESARC. Weighted percentages and means were computed to derive associations with prospectively ascertained comorbidities, treatment, and mental functioning among respondents with and without a comorbid anxiety disorders among individuals with BP. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all analyses were estimated computed and because the combined standard error of 2 means (or percentages) is always equal to or less than the sum of the standard errors of those 2 means, we conservatively consider that two CIs that share a boundary or do not overlap to be significantly different from one another (Agresti, 2002). Odds ratios (ORs) for clinical characteristics of BP, new onset of comorbidities and treatment for BP were adjusted for age, sex, race and income. All p-values are based on two-tailed tests with α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Prevalence and Sociodemographic Correlates

Sixty percent of individuals with BP met lifetime criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime anxiety disorder (51.5% GAD, 47.8% social anxiety disorder, and 53.4% panic disorder) and 40% had 2 or more lifetime anxiety disorders. The age of onset of BP was not significantly different between individuals with versus without anxiety disorders (Mean±SE, 25.33±0.55 vs. 24.03±0.5, F=3.14, p=0.08). The age of onset of anxiety disorders preceded the age onset of BP in individuals with both disorders (22.14±0.59 vs. 25.33±0.55). In addition, the age of onset of substance use disorders (SUD) was not significantly different between individuals with versus without anxiety (21.28±0.47 vs. 21.55±0.43, F=0.17, p=0.68).

As shown in Table 1, individuals over 30 years of age had greater odds of having BP with anxiety disorders than those aged 19 to 29 years. Women and unemployed individuals had greater odds of BP with anxiety disorders. Blacks and Hispanics had lower odds, whereas Native Americans had greater odds of lifetime BP with anxiety disorders compared to Whites. Widowhood, separation or divorce increased the odds of BP with anxiety disorders when compared to being married, whereas having never been married decreased the odds of BP with anxiety disorders. In addition, we found that the number of years with BP increased the risk of lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders (OR=1.03; 95%CI=1.01–1.04, p-value=0.0006).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics for Lifetime BP with versus without Anxiety Disorders

| BP with Anxiety | BP without Anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=725; %=2.09 | N=875; %=2.38 | ||||||

| % | SE | % | SE | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–29 | 27.13 | 2.18 | 43.13 | 2.33 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.0001 |

| 30–44 | 39.00 | 2.45 | 31.83 | 1.97 | 1.95 | 1.42–2.68 | |

| 45–64 | 29.55 | 2.03 | 21.35 | 1.67 | 2.20 | 1.60–3.03 | |

| 65+ | 4.31 | 0.75 | 3.69 | 0.71 | 1.86 | 1.06–3.25 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 38.73 | 2.18 | 49.52 | 2.16 | 0.64 | 0.49–0.84 | 0.002 |

| Female | 61.27 | 2.18 | 50.48 | 2.16 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 75.08 | 2.12 | 67.46 | 2.48 | 1.00 | 1.00–0.47 | 0.002 |

| Black | 9.68 | 1.11 | 13.65 | 1.34 | 0.64 | 0.65–0.44 | |

| Native American | 5.05 | 1.29 | 3.34 | 0.81 | 1.36 | 0.37–1.00 | |

| Asian | 2.74 | 0.99 | 2.92 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.86–2.83 | |

| Hispanic | 7.46 | 1.26 | 12.64 | 1.83 | 0.53 | 1.61–0.75 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 52.41 | 2.13 | 48.67 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.0002 |

| Widowed/separated/divorce | 22.99 | 1.73 | 15.36 | 1.17 | 1.39 | 0.47–1.00 | |

| Never married | 24.60 | 2.07 | 35.97 | 2.04 | 0.64 | 1.88–0.86 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 18.64 | 1.85 | 17.41 | 1.60 | 1.14 | 0.82–0.85 | 0.5 |

| High school graduate | 30.49 | 2.17 | 28.54 | 1.95 | 1.14 | 1.00–1.58 | |

| Some college or higher | 50.88 | 2.36 | 54.06 | 1.97 | 1.00 | 1.52–1.00 | |

| Employment Status | |||||||

| Employed | 60.24 | 2.21 | 67.18 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.09 | 0.009 |

| Unemployed | 39.76 | 2.21 | 32.82 | 1.84 | 1.35 | 1.00–1.68 | |

| Personal Income | |||||||

| 0–19,999 | 60.86 | 2.29 | 56.55 | 2.02 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.4 |

| 20,000–34,999 | 20.32 | 1.80 | 23.93 | 1.72 | 0.79 | 0.59–1.06 | |

| 35,000–69,999 | 14.99 | 1.62 | 16.18 | 1.48 | 0.86 | 0.60–1.23 | |

| ≥70,000 | 3.83 | 0.83 | 3.34 | 0.74 | 1.06 | 0.58–1.96 | |

Risk Factors

The odds of family history of depression and substance use disorders were significantly greater for BP with versus without anxiety disorders. Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders were more likely to have been exposed to childhood risk factors, such as vulnerable family environment, and low self esteem than those without anxiety disorders. Social support and history of divorce or loss of spouse were the adult risk factors associated with anxiety among individuals with BP (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Lifetime BP with versus without Anxiety Disorders

| BP with Anxiety | BP without Anxiety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=725; %=2.09 | N=875; %=2.38 | |||||||

| % or MEAN | SE | % or MEAN | SE | OR | 95% CI | t | p-value | |

| Family history | ||||||||

| Depression | 74.56 | 2.21 | 67.09 | 1.99 | 1.44 | 1.06–1.94 | 0.02 | |

| Alcohol problems | 62.14 | 2.19 | 51.34 | 1.99 | 1.56 | 1.22–1.99 | 0.0005 | |

| Drug problems | 39.20 | 2.13 | 32.58 | 1.99 | 1.33 | 1.03–1.72 | 0.03 | |

| Childhood | ||||||||

| Parental loss | 10.53 | 1.39 | 8.31 | 1.05 | 1.30 | 0.87–1.94 | 0.2 | |

| Vulnerable family environment | 5.20 | 0.21 | 4.18 | 0.20 | 3.46 | 0.0001 | ||

| Early onset of anxiety disorders | 47.26 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.87 | <0.0001 | ||

| Conduct disorder | 2.28 | 0.62 | 1.99 | 0.55 | 1.15 | 0.52–2.56 | 0.7 | |

| Low self-esteem | 45.17 | 2.23 | 25.46 | 1.85 | 2.41 | 1.86–3.14 | <0.0001 | |

| Adult | ||||||||

| Social support | 20.06 | 0.33 | 18.35 | 0.21 | 4.34 | 0.0001 | ||

| History of divorce/loss spouse | 42.50 | 2.22 | 30.46 | 1.80 | 1.69 | 1.31–2.17 | 0.0002 | |

| Low emotional reactivity | 25.07 | 2.03 | 26.28 | 1.88 | 0.94 | 0.71–1.24 | 0.6 | |

Clinical Characteristics of BP and Mental Health Treatment

Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders were significantly more likely than those without anxiety disorders to have BP-I versus BP-II (Table 3). Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders had greater adjusted odds for any depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes, greater number of depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes, and higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts between Wave 1 and Wave 2 compared to those without anxiety disorders (Table 3). Regarding mental health treatment, adjusted odds for sought counselor, medication, and any treatment, for both depression and mania/hypomania, were significantly greater for BP with versus without anxiety disorders. Furthermore, individuals with BP and anxiety disorders had significantly more emergency room visits for depression (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics, New Onset of Comorbidities, and Treatment for Lifetime BP with versus without Anxiety Disorders since Wave 1

| BP with Anxiety N=725; %=2.09 |

BP without Anxiety N=875; %=2.38 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or MEAN | SE | % or MEAN | SE | AOR* | 95%CI* | t*/Wa ld Chi Sq* | p-value* | |

| Clinical Characteristics of BP | ||||||||

| BP subtype | ||||||||

| BP-I | 78.03 | 1.88 | 70.54 | 1.90 | 1.37 | 1.03–1.83 | 4.95 | 0.03 |

| BP-II | 21.97 | 1.88 | 29.46 | 1.90 | 1(ref) | |||

| Any MDE | 54.58 | 2.23 | 39.19 | 2.05 | 1.39 | 1.33–2.24 | 2.25 | <0.0001 |

| Number of MDE | 3.37 | 0.24 | 2.76 | 0.16 | 1.45 | 0.03 | ||

| Length of MDE (week)** | 11.85 | 1.20 | 9.94 | 1.12 | 0.2 | |||

| Recovery from depression | 71.78 | 4.92 | 84.60 | 4.64 | 0.47 | 0.18–1.19 | 0.1 | |

| Any manic/hypomanic episodes | 41.46 | 2.30 | 29.5 | 1.99 | 1.83 | 1.35–2.48 | 2.59 | <0.0001 |

| Number of manic/hypomanic episodes | 3.63 | 0.25 | 2.72 | 0.29 | 1.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Length of mania (week)** | 6.30 | 0.98 | 5.31 | 5.31 | 0.3 | |||

| Recovery from mania | 73.64 | 4.56 | 79.68 | 4.73 | 0.71 | 0.33–1.52 | 0.4 | |

| Attempted suicide | 8.57 | 1.84 | 6.08 | 1.65 | 1.56 | 0.74–3.30 | 0.2 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 35.67 | 2.80 | 25.74 | 3.08 | 1.66 | 1.07–2.57 | 0.02 | |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | 27.85 | 2.68 | 18.74 | 2.61 | 1.64 | 1.05–2.56 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| Earliest suicide attempt | 23.66 | 1.33 | 24.12 | 2.31 | 0.24 | 0.6 | ||

| Recent suicide attempt | 30.84 | 1.85 | 31.19 | 2.29 | 0.8 | |||

| New Onset of Comorbidites | ||||||||

| Any Anxiety Disorders | 16.89 | 1.63 | 16.08 | 1.50 | 1.04 | 0.74–1.48 | 0.8 | |

| PANIC | 11.99 | 2.11 | 4.27 | 1.15 | 3.37 | 0.99–5.70 | <0.001 | |

| SAD | 9.25 | 1.93 | 6.48 | 0.97 | 1.64 | 0.92–2.94 | 0.09 | |

| GAD | 12.63 | 1.76 | 9.35 | 0.69 | 1.34 | 0.88–2.06 | 0.2 | |

| Alcohol Use Disorders | 12.59 | 2.06 | 20.15 | 2.05 | 0.76 | 0.49–1.17 | 0.2 | |

| Drug Use Disorders | 9.46 | 1.60 | 6.74 | 1.11 | 1.76 | 1.07–2.88 | 0.02 | |

| Nicotine Dependence | 6.95 | 1.85 | 7.81 | 1.34 | 0.98 | 0.50–1.94 | 0.9 | |

| Treatment for BP | ||||||||

| Counselor for MDE | 51.61 | 3.09 | 32.42 | 3.18 | 2.01 | 1.35–3.00 | 0.0005 | |

| Hospitalized for MDE | 13.25 | 2.15 | 7.92 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 0.94–3.29 | 0.07 | |

| Emergency room for MDE | 15.21 | 2.40 | 7.29 | 1.72 | 2.29 | 1.21–4.34 | 0.01 | |

| Medication for MDE | 51.90 | 3.10 | 34.27 | 3.36 | 1.87 | 1.24–2.84 | 0.003 | |

| Sought any treatment for MDE | 59.79 | 3.03 | 39.73 | 3.25 | 2.05 | 1.38–3.06 | 0.0003 | |

| Counselor for mania/hypomania | 33.66 | 3.59 | 17.78 | 3.02 | 2.02 | 1.08–3.78 | 0.03 | |

| Hospitalized for mania/hypomania | 6.41 | 2.01 | 4.73 | 1.45 | 1.56 | 0.57–4.30 | 0.4 | |

| Emergency room for mania/hypomania | 6.45 | 1.96 | 3.93 | 1.33 | 1.86 | 3.06–3.78 | 0.3 | |

| Medication for mania/hypomania | 33.93 | 3.20 | 18.24 | 2.99 | 1.99 | 1.15–3.43 | 0.01 | |

| Sought any treatment for mania/hypomania | 40.94 | 3.44 | 22.92 | 3.40 | 2.04 | 1.18–3.56 | 0.01 | |

Abbreviations: BP=Bipolar Disorder, BP-I= Bipolar Disorder I, BP-II= Bipolar Disorder II. MDE=Major Depressive Episode, SAD=Separation Anxiety Disorder, GAD=Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

AOR is adjusted by age, gender, race and income;

longest duration

Incidence of Comorbidities

Adjusted odd showed significantly higher incidence of panic disorder and more drug use disorders in individuals with BP with versus without anxiety disorders (Table 3).

Mental Functioning and Social Readjustment

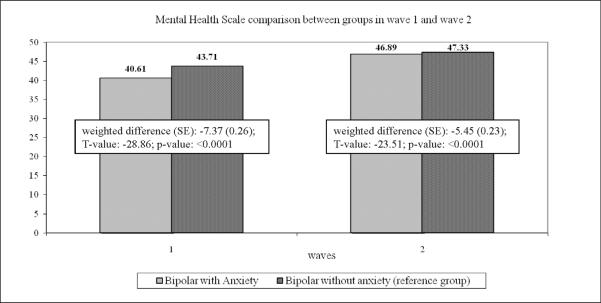

Individuals with BP with versus without anxiety disorders had significantly lower scores on mental health scale comparison in Wave 1 and Wave 2, indicating greater disability on mental functioning (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In addition, individuals with BP with anxiety disorders had significantly more trouble at work (AOR=1.55; 95%CI: 1.11–2.17; p=0.009), more financial crisis (AOR=1.43; 95%CI: 1.09–1,88; p=0.009), more death of family or close friends (AOR=1.31; 95%CI:1.01–1.71; p=0.04), and more family/close friends have been physically assaulted (AOR=1.83; 95%CI: 1.09–3.07; p=0.02). There were not other significant differences in measures of social readjustment.

DISCUSSION

In a large, nationally representative sample of US adults, 60% of individuals with BP had at least one comorbid anxiety disorder. Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders shared lifetime risk factors for MDD, and had more depressive and mania/hypomania episodes, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and higher rates of treatment-seeking than those without anxiety disorders. They also had higher incidence of panic disorder and drug use disorders, and poorer mental health functioning than individuals with BP without anxiety disorders.

The present findings are consistent with the high prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in previous clinical (Boylan et al., 2004; McElroy et al., 2001; Pini et al., 1997) and epidemiological (Chen et al., 1995a; b; Kessler et al., 1997; Merikangas et al., 2011; Perlis et al., 2004; Szadoczky, Papp, Vitrai, Rihmer, & Furedi, 1998) studies of adults with BP. We found that individuals with BP and anxiety disorders were more likely to have a diagnosis of BP-I as did clinical (McElroy et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2004) and epidemiologic studies (Merikangas et al., 2011), contrary to other clinical studies in youth (Masi et al., 2007; Sala et al., 2010) and adults (Cassano et al., 1999; Doughty et al., 2004; Henry et al., 2003; Perugi et al., 1999). Recently, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) (Merikangas et al., 2007) found no significant differences in comorbid anxiety disorders in BP-I versus BP-II (86.7% vs. 89.3%).

On average, the onset of anxiety disorders preceded the onset of BP in individuals with both disorders and supports the idea that anxiety disorders could be a risk factor for subsequent development of BP (Goldstein & Levitt, 2007). Interestingly, recent studies found that offspring of parents with BP had higher rates of anxiety disorders than offspring of control parents suggesting that anxiety may be a precursor of BP among BP offspring (Birmaher et al., 2009; Goldstein et al.). At the same time, we found that the duration of years ill with BP increased the risk of lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders. This raises the question of whether this could be a sensitization-like phenomenon occurring as a consequence of the progression of the BP.

Our findings converge with previous clinical studies showing that comorbid anxiety disorders among individuals worsen the course of BP, being associated with more major depressive (MDE) (Gaudiano et al., 2005; Mantere et al., 2010) and mania/hypomania episodes, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Bauer et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2004; Simon et al., 2007; Young, Cooke, Robb, Levitt, & Joffe, 1993). In addition, we found higher rates of treatment-seeking for either MDE and mania/hypomania episodes, which may reflect the poor treatment response of these individuals (Feske et al., 2000; Frank et al., 2002; Henry et al., 2003; Pini et al., 2003) or the need of more treatment for the severity associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in BP. Furthermore, more emergency room visits for MDE were found confirming evidence of the severity of depressive episodes in individuals with BP and anxiety disorders (Gaudiano et al., 2005).

Individuals with BP and anxiety disorders had higher prevalence of several of the risk factors first identified by Kendler for depression (Kendler et al., 2002; 2006) and more recently by our group for GAD (Vesga-Lopez et al., 2008). Overall, these findings suggest that those factors may increase the risk for a broader range of disorders beyond depression. Recently, Mantere and colleagues (2010) (Mantere et al., 2010) found strong evidence for the concurrent and longitudinal association between anxiety and depressive but not manic symptoms in BP suggesting a probable manifestation of the same illness propensity.

Epidemiological as well as clinical studies have shown that adults (Chengappa, Levine, Gershon, & Kupfer, 2000; Grant et al., 2004) with BP are at high risk for SUD, and both BP and SUD are strongly associated with anxiety disorders (Goldstein et al., 2008). Our findings also showed that individuals with BP and anxiety disorders had higher incidence of drug use disorders than those without anxiety, suggesting the possibility that early recognition and treatment of these individuals may prevent the development of drug use disorders. At the same time, we found that age onset of SUD preceded the age onset of BP and anxiety disorders in individuals with versus without anxiety suggesting that individuals with SUD might be at high risk to develop both disorders.

Furthermore, individuals with BP and anxiety disorders had higher incidence of panic disorder than those without anxiety disorders. This may reflect continuity of anxiety disorders across diagnostic subtype (heterotypic continuity) (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Ferdinand, Dieleman, Ormel, & Verhulst, 2007). Alternatively, the association of panic disorder and BP could be specific rather than mere realizations of larger processes involving both internalizing disorders (Kessler et al., 2011).

Confirming evidence of previous studies (Bauer et al., 2005; Boylan et al., 2004; McElroy et al., 2001; Otto et al., 2006), individuals with BP and anxiety showed poorer psychosocial functioning. These individuals can experience work, family and social impairment and be made to contend with increased health care costs and strains on family support (Post, 2005).

The present findings might suggest that BP and anxiety disorders are disorders with overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms, as suggested by their high rate of co-occurrence (Angst, 1998; Chen et al., 1995a; b; Kessler et al., 1994), shared genetic variance (MacKinnon et al., 1998; Wozniak, Biederman, Monuteaux, Richards, & Faraone, 2002), shared biological mechanisms including heightened noradrenergic and dopaminergic activity (Freeman, Freeman, & McElroy, 2002; McElroy et al., 2001), and neuroimaging studies showing amygdala volume reductions in adults with anxiety disorders (Rauch, Shin, & Wright, 2003) and BP (Blumberg et al., 2003).

Taken together, the above-noted findings indicate that anxiety disorders may uniquely contribute to BP severity independently of other common comorbidities such as SUD (Goldstein et al., 2008; McElroy et al., 2001). The greater persistence of anxiety disorders over time, particularly in individuals with more severe anxiety (Sala et al., 2011) may explain in part the high association between anxiety disorders and BP and could be a unique factor that negatively influences BP severity and prognosis (Coryell et al., 2009; Gaudiano et al., 2005; Otto et al., 2006). These findings are clinically relevant because currently the first line pharmacological treatment for anxiety disorders, in the absence of BP, are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Bandelow, Zohar, Hollander, Kasper, & Moller, 2002; Kasper, Stein, Loft, & Nil, 2005), which may trigger or destabilize BP symptoms (Ghaemi, Hsu, Soldani, & Goodwin, 2003). However, there have been very few double-blind, controlled trials examining the treatment response of individuals with BP and anxiety disorders (Kauer-Sant'Anna, Kapczinski, & Vieta, 2009; Rakofsky & Dunlop, 2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for example, has been shown to be highly effective in anxiety disorders and in BP (Lam et al., 2003), but no studies to our knowledge have examined CBT for anxiety in BP specifically. From a clinical standpoint, our findings highlight the importance of early targeting anxiety disorders, and the need for implementing/developing effective psychotherapeutic approaches that treat anxiety in individuals with BP. Focusing on the treatment of comorbid anxiety disorders may lessen the negative clinical course and psychological functioning of those subjects with BP. Further studies examining specific interventions for anxiety disorders in BP are needed.

The potential limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, the NESARC interviews were conducted by lay professional interviewers rather than clinicians. However, the NESARC interviewers received extensive training with a highly structured and well-validated diagnostic assessment instrument (Grant et al., 2003a). Second, not all respondents from Wave 1 were able to be interviewed in Wave 2. Reasons for the decline included respondents who were deceased, institutionalized, or unwilling to participate at the time of the second interview. However, statistical adjustments were made for nonresponse. Furthermore, although not all respondents were available for re-interview, the response rate of Wave 2 was 86.7% (Grant et al., 2008), a much higher figure than other nationally representative surveys.

This study has also some important strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative longitudinal study examining the course and outcome of individuals with BP and anxiety disorders. Second, it examined multiple specific anxiety disorders. Finally, we included in the study both BP-I and BP-II. Although most previous clinical studies (Bauer et al., 2005; Boylan et al., 2004; Henry et al., 2003; MacQueen et al., 2003; McElroy et al., 2001; Otto et al., 2006; Perlis et al., 2004; Pini et al., 1997; Simon et al., 2004; Simon et al., 2007; Young et al., 1993) included BP-II, to our knowledge few epidemiologic studies (Angst et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2007; Merikangas et al., 2011; Perlis et al., 2004) examining anxiety comorbidity in BP did so.

In summary, this study showed that anxiety disorders are highly prevalent among individuals with BP and are prospectively associated with elevated BP severity and BP-related health service use. In addition, our study extended previous findings by demonstrating that anxiety disorders predicted the incidence of panic disorders, drug use disorders, and increased psychosocial impairment. These epidemiologic findings are important because they confirm that the association between anxiety disorders and illness severity in BP exists in unselected samples, and is not restricted to tertiary clinical settings in academic health science centers where many clinical samples are recruited. Given the clinical and treatment implications of these epidemiological findings and the additional contribution on previous clinical research in this field support that early identification and accurate diagnosis are warranted. Further studies examining specific interventions for anxiety in individuals with BP are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dr. Sala and Dr. Morcillo were supported by a grant from the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Work on this manuscript was supported by NIH grants DA019606, DA020783, DA023200, DA023973, MH082773, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Dr. Blanco).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Wiley and Sons, Inc; John Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Albert U, Rosso G, Maina G, Bogetto F. Impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity on quality of life in euthymic bipolar disorder patients: differences between bipolar I and II subtypes. J Affect Disord. 2008;105:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:143–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, Hantouche E, Goodwin R, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes and disorders: significance of comorbidity with bipolar and anxiety syndromes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Moller HJ. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2002;3:171–99. doi: 10.3109/15622970209150621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Beresford T, Williford WO, Hauger R. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:301–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, Kalas C, Goldstein B, Hickey MB, Obreja M, Ehmann M, Iyengar S, Shamseddeen W, Kupfer D, Brent D. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287–96. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Markowitz JC, Liu SM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. The epidemiology of chronic major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1645–56. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05663gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Kaufman J, Martin A, Whiteman R, Zhang JH, Gore JC, Charney DS, Krystal JH, Peterson BS. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1201–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan KR, Bieling PJ, Marriott M, Begin H, Young LT, MacQueen GM. Impact of comorbid anxiety disorders on outcome in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1106–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Dell'Osso L. Multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:474–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. 1995a;59:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1995b;152:280–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, Kupfer DJ. Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:191–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Solomon DA, Fiedorowicz JG, Endicott J, Schettler PJ, Judd LL. Anxiety and outcome in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1238–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty CJ, Wells JE, Joyce PR, Olds RJ, Walsh AE. Bipolar-panic disorder comorbidity within bipolar disorder families: a study of siblings. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:245–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand RF, Dieleman G, Ormel J, Verhulst FC. Homotypic versus heterotypic continuity of anxiety symptoms in young adolescents: evidence for distinctions between DSM-IV subtypes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:325–33. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Houck PR, Fagiolini A, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Kupfer DJ. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:956–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Cyranowski JM, Rucci P, Shear MK, Fagiolini A, Thase ME, Cassano GB, Grochocinski VJ, Kostelnik B, Kupfer DJ. Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:905–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA, Miller IW. Anxiety disorder comobidity in Bipolar I Disorder: relationship to depression severity and treatment outcome. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:71–7. doi: 10.1002/da.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Soldani F, Goodwin FK. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: the case for caution. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:421–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar I disorder among adults with primary youth-onset anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2007;103:187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. The specific burden of comorbid anxiety disorders and of substance use disorders in bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Shamseddeen W, Axelson DA, Kalas C, Monk K, Brent DA, Kupfer DJ, Birmaher B. Clinical, demographic, and familial correlates of bipolar spectrum disorders among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 49:388–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Hoven CW. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2002;70:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Kaplan K, Moore T, Kimball J. Source and accuracy statement for the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:533–45. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003a;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, June Ruan W, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Saha TD, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, comorbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2005b;35:1747–59. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Patricia Chou S, June Ruan W, Huang B. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2005c;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and accuracy statement for wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry C, Van den Bulke D, Bellivier F, Etain B, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. Anxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: prevalence and impact on illness severity and response to mood stabilizer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1967 doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Stein DJ, Loft H, Nil R. Escitalopram in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: randomised, placebo-controlled, flexible-dosage study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:222–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.3.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer-Sant'Anna M, Kapczinski F, Vieta E. Epidemiology and management of anxiety in patients with bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:953–64. doi: 10.2165/11310850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1133–45. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:115–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Stein DJ, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade L, Benjet C, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam A, Lee S, Lepine JP, Matchsinger H, Mihaescu-Pintia C, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Ustun TB. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1079–89. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P, Bright J, Wright K, Kerr N, Parr-Davis G, Sham P. A randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder: outcome of the first year. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:145–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DF, Xu J, McMahon FJ, Simpson SG, Stine OC, McInnis MG, DePaulo JR. Bipolar disorder and panic disorder in families: an analysis of chromosome 18 data. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:829–31. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Begin H, Robb J, Joffe RT, Young LT. Subsyndromal symptoms assessed in longitudinal, prospective follow-up of a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:349–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantere O, Isometsa E, Ketokivi M, Kiviruusu O, Suominen K, Valtonen HM, Arvilommi P, Leppamaki S. A prospective latent analyses study of psychiatric comorbidity of DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:271–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G, Perugi G, Millepiedi S, Toni C, Mucci M, Bertini N, Pfanner C, Berloffa S, Pari C, Akiskal K, Akiskal HS. Clinical and research implications of panic-bipolar comorbidity in children and adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr., Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, Rochussen JR, Rush AJ, Post RM. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:420–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, Viana MC, Andrade LH, Hu C, Karam EG, Ladea M, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Wells JE, Zarkov Z. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241–51. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Simon NM, Wisniewski SR, Miklowitz DJ, Kogan JN, Reilly-Harrington NA, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Marangell LB, Sagduyu K, Weiss RD, Miyahara S, Thas ME, Sachs GS, Pollack MH. Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:20–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Ramacciotti S, Nassini S, Toni C, Milanfranchi A, Musetti L. Depressive comorbidity of panic, social phobic, and obsessive-compulsive disorders re-examined: is there a bipolar II connection? J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, Savino M, Russo A, Montgomery SA. Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Dell'Osso L, Amador XF, Mastrocinque C, Saettoni M, Cassano GB. Awareness of illness in patients with bipolar I disorder with or without comorbid anxiety disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:355–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM. The impact of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 5):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Treating nonspecific anxiety and anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:81–90. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05815gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Shin LM, Wright CI. Neuroimaging studies of amygdala function in anxiety disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:389–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala R, Axelson D, Castro-Fornieles J, Goldstein T, Goldstein B, Ha W, Liao F, Gill M, Iyengar S, Strober M, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt J, Ryan N, Dickstein D, Keller M, Birmaher B. Factors associated with the persistence and the onset of new anxiety disorders in youth with bipolar spectrum disorders. In press at J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala R, Axelson DA, Castro-Fornieles J, Goldstein TR, Ha W, Liao F, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt J, Ryan ND, Dickstein D, Keller MB, Birmaher B. Comorbid anxiety in children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: prevalence and clinical correlates. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1344–50. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05845gre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Pollack MH. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Smoller JW, Fava M, Sachs G, Racette SR, Perlis R, Sonawalla S, Rosenbaum JF. Comparing anxiety disorders and anxiety-related traits in bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:187–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Zalta AK, Otto MW, Ostacher MJ, Fischmann D, Chow CW, Thompson EH, Stevens JC, Demopulos CM, Nierenberg AA, Pollack MH. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:255–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szadoczky E, Papp Z, Vitrai J, Rihmer Z, Furedi J. The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary. Results from a national epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:153–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesga-Lopez O, Schneier FR, Wang S, Heimberg RG, Liu SM, Hasin DS, Blanco C. Gender differences in generalized anxiety disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1606–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B. How to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey. Quality Metrics; Lincoln, RI: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Richards J, Faraone SV. Parsing the comorbidity between bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders: a familial risk analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:101–11. doi: 10.1089/104454602760219144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LT, Cooke RG, Robb JC, Levitt AJ, Joffe RT. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]