Abstract

A 29-year-old pregnant woman with recurrent pericardial effusion and a cardiac tumor, diagnosed as an angiosarcoma, was treated with surgical resection of the tumor followed by radiotherapy. Immediately after completion of radiotherapy, she developed bilateral breast masses, which were also confirmed as angiosarcomas. We thought this might be the first case of bilateral angiosarcoma of the breast metastasizing to heart mimicking a primary cardiac angiosarcoma, although we could not conclude with certainty that angiosarcoma of the heart was not the primary site.

Keywords: Hemangiosarcoma, Breast, Heart

INTRODUCTION

Angiosarcomas are rare tumors, accounting for approximately 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas. They occur more frequently in specific sites such as skin, soft tissue, and breasts, but they can arise in any part of the body. Angiosarcoma of the breast occurs sporadically in young women, and, interestingly, bilateral disease can occur and is usually associated with pregnancy [1]. Primary cardiac angiosarcoma is the most common cardiac sarcoma, representing up to one-third of cases, however, primary cardiac sarcomas are still very rare with an incidence of 0.0001% in collected autopsy series [2]. We report a case of a pregnant woman with angiosarcoma of the bilateral breast who initially presented with orthopnea and recurrent pericardial effusion due to angiosarcoma of the heart, which may have been a metastatic tumor rather than a primary angiosarcoma.

CASE REPORT

A 29-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0) at 32 weeks and 5 days of gestation was referred to the Department of Obstetrics at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, for evaluation of her recurrent pericardial effusion. Two months prior, she had experienced progressive orthopnea due to pericardial effusion and underwent pericardiocentesis at another hospital, however, no definitive diagnosis was made at that time. As her echocardiography showed large amounts of pericardial effusion only, she underwent pericardiocentesis to relieve her progressive orthopnea. The analysis of pericardial fluid returned 2,440 white blood cells/mm3 with a differential revealing 49% neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes, and 30% histiocytes. The chemistry panel showed a pH of 7.4, glucose level of 59 mg/dL, protein level of 4.9 g/dL, and lactate dehydrogenase level of 403 IU/L. However, neither malignant cells nor microorganisms were identified in her pericardial fluid. Soon after, she delivered a child prematurely at 36 weeks and 3 days of gestation and was followed closely by an outpatient clinic. Four months after the delivery, however, she presented to an emergency room with the same symptoms as her first visit. At this time, her echocardiography showed a large amount of pericardial effusion and her computed tomography (CT) showed not only pericardial effusion, but also a soft tissue-like intracardiac mass in the anterior side of right atrial wall (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart revealed a soft tissue mass along the right atrium encasing the right coronary artery (Fig. 2). Positron emission tomography CT showed a 7-cm hypermetabolic mass along the right atrium with an SUVmax value of 7.8 and hypermetabolic lesions in both breasts with SUVmax values of 6.8 and 6.4, which were diagnosed as related to lactation (Fig. 3). She underwent open-heart surgery due to a strong suspicion of cardiac malignancy. The mass originated from the right atrium along the atrioventricular groove and encased the right coronary artery. It measured 7.5 × 6 × 3.5 cm with an ill-demarcated, dark brownish, firm, and trabeculated lesion with multiple hemorrhagic foci. The pathology was confirmed as angiosarcoma (Fig. 4) with involvement of resection margin, of which immunohistochemistry for CD34 and CD31 showed positivity. A postoperative MRI revealed a residual tumor around the right coronary artery and as a result, the patient received 56 Gy of radiotherapy to the heart. One month after completion of the radiotherapy, she complained of bilateral palpable breast masses. The repeat CT showed multiple enhancing breast masses (Fig. 5) and fine-needle aspiration of the breast masses revealed a spindle cell sarcoma similar to the prior pathology of angiosarcoma of the heart (Fig. 6).

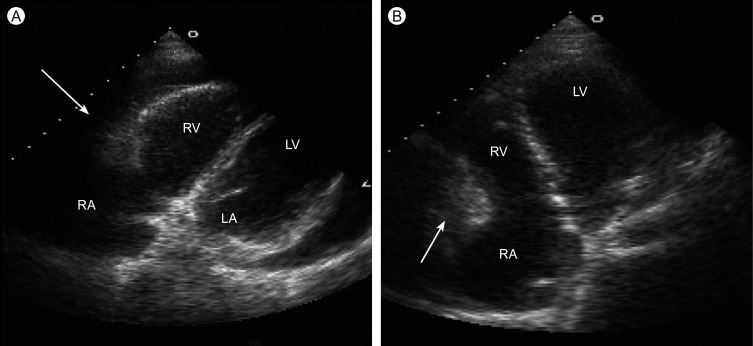

Figure 1.

The echocardiography shows an intra-cardiac mass (arrow) in the anterior side of right atrial wall. (A) Modified parasternal view. (B) Apical four chamber view. RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; RV, left ventricle.

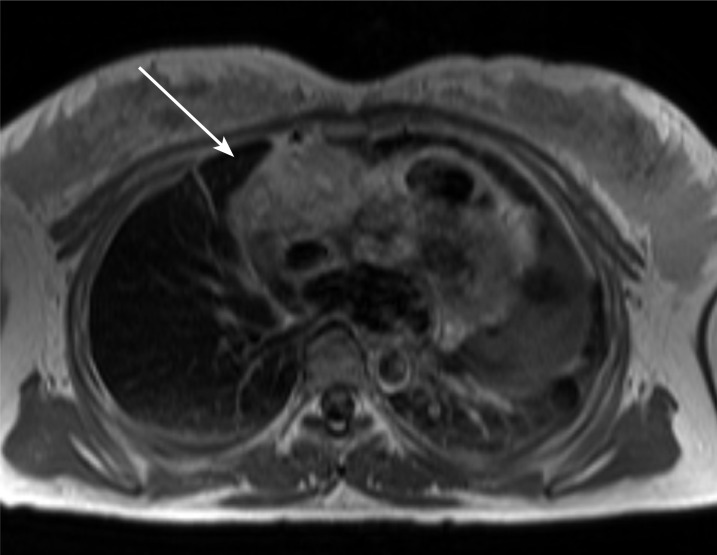

Figure 2.

The magnetic resonance imaging of the heart shows an intra-cardiac mass (arrow) in the anterior side of the right atrial wall encasing a right coronary artery.

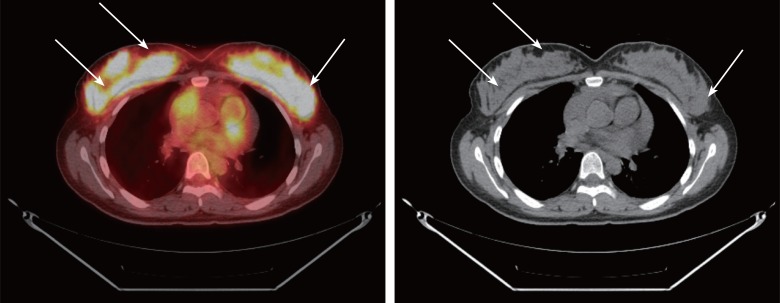

Figure 3.

The positron emission tomography shows hypermetabolic lesions in both breast masses (arrows).

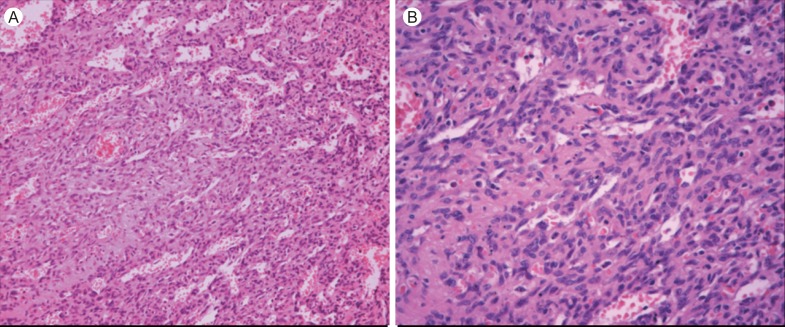

Figure 4.

The pathology of the cardiac tumor confirms angiosarcoma with vasoformitive architectures. (A) H&E, × 200. (B) H&E, × 400.

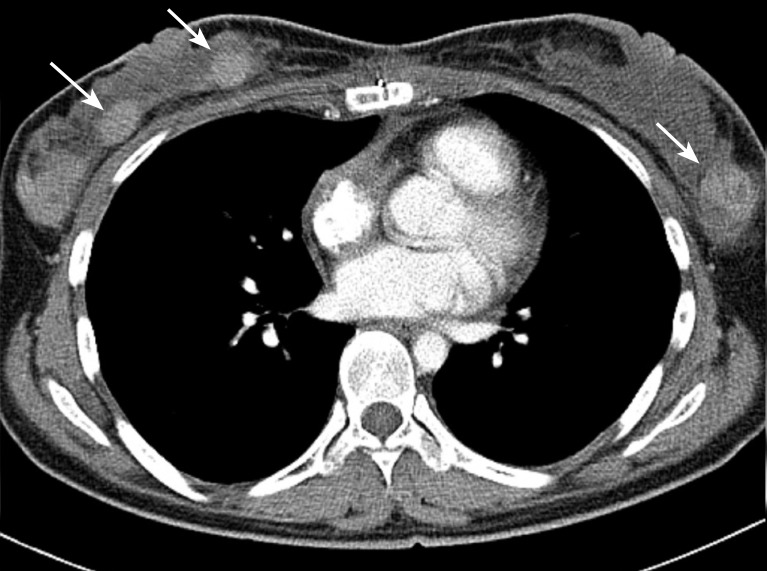

Figure 5.

Serial computed tomography shows the bilateral breast masses (arrows).

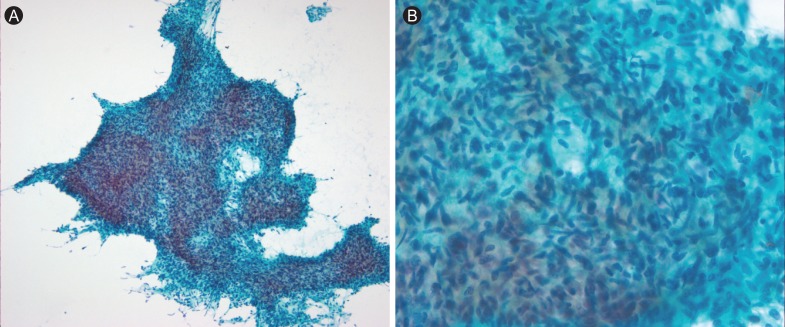

Figure 6.

The pathology of the breast masses reveals spindle cell sarcoma similar to previous angiosarcoma of the heart. (A) Pap, × 100. (B) Pap, × 400.

DISCUSSION

Soft tissue angiosarcomas are highly aggressive tumors with one-half of patients expected to die within the first year after diagnosis with metastatic disease. Angiosarcoma of the breast is a rare disease, accounting for 0.04% of all malignant breast tumors [3]. They are commonly divided into two subtypes, primary and secondary angiosarcoma; primary angiosarcoma of the breast usually arises within the breast parenchyma in women between 20-50 years of age without recognized associated factors [4,5], while secondary angiosarcoma of the breast is associated with a number of presumed etiologic factors, such as old age and post-radiation or post-mastectomy with axillary dissection [6]. Of particular interest is that bilateral disease can occur and is usually associated with pregnancy, and contralateral involvement may be due to either development of a second primary tumor or metastasis [1]. The most common sign is a painless mass or diffuse breast enlargement. In particular, discoloration of the overlying skin is more specific, however, this occurs in only 17-35% of patients [1].

On the other hand, angiosarcoma of the heart is more common as it is the most frequently found cardiac tumor [7]. However, cardiac sarcoma itself is a very rare disease with an incidence of only 0.0001% in collected autopsy series [2]. The disease is 2-3 times more common in men than in women. This tumor typically presents with clinical symptoms related to right-sided congestive heart failure or pericardial disease because the right atrium is the most common site of origin and is often accompanied by hemorrhagic pericardial effusion. In addition, angiosarcomas of the heart presenting with pericardial effusion in pregnant women have also been reported [8].

Initially, the patient in this case was diagnosed with pericardial effusion related to pregnancy. Although symptomatic effusion seems rare, many pregnant women develop a minimal to moderate amount of pericardial effusion by the third trimester of pregnancy. However, because she presented with recurrent pericardial effusions and a cardiac mass in the right atrium 4 months after delivery, the diagnosis changed to angiosarcoma of the heart with recurrent malignant pericardial effusion. Unexpectedly, during the follow-up period, bilateral breast masses were found and pathology confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. In retrospect, they may have existed at the time of initial presentation but were masked by the diffuse hypermetabolic state of the breast due to lactation. We presumed that the patient's diagnosis was more likely to be primary angiosarcoma of the breast metastasizing to the heart because angiosarcoma of the breast is more common than angiosarcoma of the heart [1,2] and because bilateral breast angiosarcoma is often associated with pregnancy [1]. In addition, primary angiosarcoma of the heart is more common in males than females and often produces metastatic disease in lung, liver, lymph node, or bone at the time of initial presentation [9], and in this case, we did not see metastatic disease in these organs. To the best of our knowledge, no case of metastatic angiosarcoma of the breast metastasizing to the heart or vice versa has been reported. Also, no report of primary angiosarcoma of the breast with a second primary angiosarcoma of the heart has been identified. However, primary angiosarcoma of the breast metastasizing to the heart might be a more reasonable diagnosis considering the incidence, patient's characteristics, and clinical manifestation.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Chen KT, Kirkegaard DD, Bocian JJ. Angiosarcoma of the breast. Cancer. 1980;46:368–371. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800715)46:2<368::aid-cncr2820460226>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talbot SM, Taub RN, Keohan ML, Edwards N, Galantowicz ME, Schulman LL. Combined heart and lung transplantation for unresectable primary cardiac sarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:1145–1148. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.126495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal PK, Mehrotra R. Haemangiosarcoma of the breast. Indian J Cancer. 1977;14:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West JG, Qureshi A, West JE, et al. Risk of angiosarcoma following breast conservation: a clinical alert. Breast J. 2005;11:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiluk JV, Yeh KA. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast. Breast J. 2005;11:517–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yap J, Chuba PJ, Thomas R, et al. Sarcoma as a second malignancy after treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke AP, Cowan D, Virmani R. Primary sarcomas of the heart. Cancer. 1992;69:387–395. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920115)69:2<387::aid-cncr2820690219>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azimi NA, Selter JG, Abott JD, et al. Angiosarcoma in a pregnant woman presenting with pericardial tamponade: a case report and review of the literature. Angiology. 2006;57:251–257. doi: 10.1177/000331970605700219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke AP, Virmani R. Sarcomas of the great vessels: a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1993;71:1761–1773. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930301)71:5<1761::aid-cncr2820710510>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]