Abstract

There is substantial evidence supporting a role for the endocannabinoid system as a modulator of the dopaminergic activity in the basal ganglia, a forebrain system that integrates cortical information to coordinate motor activity regulating signals. In fact, the administration of plant-derived, synthetic or endogenous cannabinoids produces several effects on motor function. These effects are mediated primarily through the CB1 receptors that are densely located in the dopamine-enriched basal ganglia networks, suggesting that the motor effects of endocannabinoids are due, at least in part, to modulation of dopaminergic transmission. On the other hand, there are profound changes in CB1 receptor cannabinoid signaling in the basal ganglia circuits after dopamine depletion (as happens in Parkinson’s disease) and following l-DOPA replacement therapy. Therefore, it has been suggested that endocannabinoid system modulation may constitute an important component in new therapeutic approaches to the treatment of motor disturbances. In this article we will review studies supporting the endocannabinoid modulation of dopaminergic motor circuits.

Keywords: endocannabinoids, dopamine, basal ganglia, motor circuits, electrophysiology

The discovery and the following investigation of the endocannabinoid system have demonstrated its implication in a large variety of functions such as regulation of appetite and energy metabolism, pain and inflammation, neuroprotection, and motor control. The endocannabinoid system is also a modulator of the basal ganglia circuitry functionality (Benarroch, 2007; Fernandez-Ruiz, 2009) and therefore, it may be considered as a potential pharmacological target for the treatment of movement disorders. This review is focused on the endocannabinoid modulation of dopaminergic motor circuits.

Neuroanatomical Evidences Supporting Dopaminergic-Endocannabinoid Interaction

The cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids and the proteins for their biosynthesis and degradation constitute the key components of the endocannabinoid system (Di Marzo et al., 1998). CB1 receptors and endocannabinoids are highly expressed in the basal ganglia and have close connections with the dopaminergic system, being involved in the central regulation of motor functions.

To date, two cannabinoid receptor subtypes have been identified by molecular cloning, cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) (Matsuda et al., 1990) and cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2) (Munro et al., 1993). The vast majority of CB1 receptors are located in the central nervous system while CB2 receptors are expressed primarily in cells of the immune system (Munro et al., 1993), microglia, blood vessels and some neurons (Van Sickle et al., 2005; Gong et al., 2006). Both CB1 and CB2 are seven transmembrane Gi/o-coupled receptors that activate similar intracellular signaling pathways (Mackie, 2008). The discovery of the cannabinoid receptors led to the identification of the so-called natural ligands of the cannabinoid receptors, anandamide (Devane et al., 1992) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Devane et al., 1992; Mechoulam et al., 1995) which are synthesized “on demand” in response to elevations of intracellular calcium (Di Marzo et al., 1994).

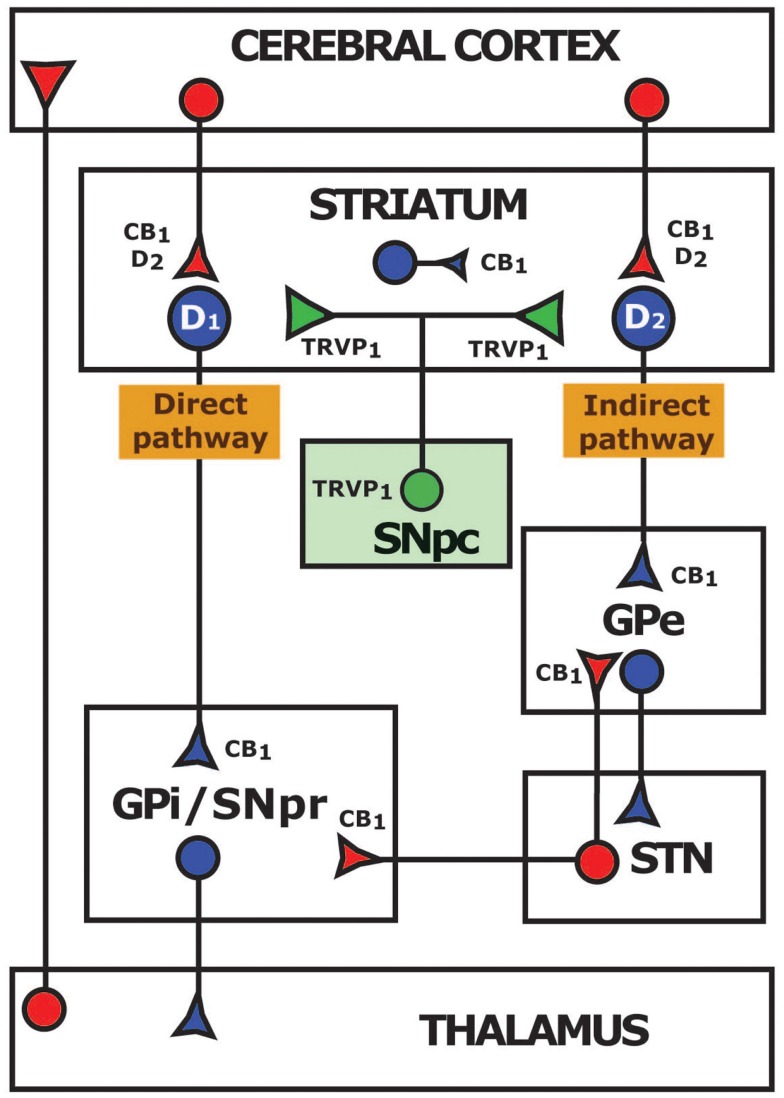

Although the expression of CB2 receptors has remained controversial (Atwood and Mackie, 2010), mRNA for this receptor has been found in neurons and glial cells from the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr) and the striatum (Gong et al., 2006). As for CB1 receptor, high levels are expressed within the basal ganglia (Herkenham et al., 1990; Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992; Tsou et al., 1998; Mackie, 2005; Martin et al., 2008). While mRNA for this receptor is found in striatal GABAergic medium spiny neurons (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992) and in the subthalamic nucleus (STN), the expression of the receptor protein is mainly located at the terminal level. Thus, CB1 receptors have been observed in subthalamonigral and subthalamopallidal terminals (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992; Tsou et al., 1998), glutamatergic corticostriatal afferences (Gerdeman and Lovinger, 2001; Kofalvi et al., 2005), and striatal projections to the globus pallidus (GPi and GPe) and to the SNpr (Herkenham et al., 1991; Tsou et al., 1998; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors and their coexpression with dopaminergic D1 and D2 receptors in a simplified diagram of the basal ganglia circuits. GABAergic inhibitory pathways are represented in blue and glutamatergic excitatory pathways in red. Modulatory dopaminergic connections are indicated in green. CB1, cannabinoid receptor type 1; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1; D1, dopaminergic receptor type 1; D2, dopaminergic receptor type 2; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus; STN, subthalamic nucleus; SNpc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNpr, substantia nigra pars reticulata.

Neurons expressing D1 receptors form the direct pathway, which projects to the GPi and the SNpr, while neurons expressing D2 receptors constitute the indirect pathway, projecting to the GPe (Figure 1) (Paul et al., 1992; O’Connor, 1998; Nicola et al., 2000; Onn et al., 2000; Svenningsson et al., 2000). A potential interaction between the D1/D2 and CB1 receptors at the level on the G-protein/adenylyl cyclase signal transduction mechanism has been suggested (Giuffrida et al., 1999; Meschler and Howlett, 2001). Combined activation of CB1 and D1 receptors results in a net decrease in adenylyl cyclase, a subsequent decrease in the inhibitory activity of direct striatal projection neurons and finally a decreased motor response due to enhanced activation of SNpr neurons. Conversely, activation of CB1 and D2 receptors together stimulates adenylyl cyclase (Glass and Felder, 1997), potentiating the indirect striatal pathway neurons that in turn activate neurons of the STN, also resulting in motor inhibition (Brotchie, 2003; van der Stelt and Di Marzo, 2003). These data indicate that endocannabinoid system acting on striatal CB1 receptors play a significant role in the regulation of basal ganglia motor circuits. Although CB1/D2 receptor heterodimerization has been demonstrated in transfected cells by co-immunoprecipitation and Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) techniques (Kearn et al., 2005; Marcellino et al., 2008), functionality of those heteromers in striatal glutamatergic terminals is not supported by recent studies (Kreitzer and Malenka, 2007).

In the last years, the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) has gained attention for its ability to bind cannabinoids. Although neuronal expression and functionality of TRPV1 channels are controversial (Mezey et al., 2000; Cristino et al., 2006; Cavanaugh et al., 2011), this receptor is present in the basal ganglia. Indeed, TRPV1 is located on nigrostriatal terminals and on tyrosine hydroxylase positive cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) (Mezey et al., 2000; Micale et al., 2009) which makes it a good candidate for directly modulating dopaminergic neurotransmission (Figure 1). On the other hand, the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) has been identified as another possible cannabinoid receptor (Ryberg et al., 2007) that, in contrast to classical CB1 and CB2, is coupled to Gq, Gα12 and Gα13 proteins (Sharir and Abood, 2010). Despite its high expression in the striatum (Sawzdargo et al., 1999), conflicting pharmacological findings make difficult to consider the GPR55 as a novel cannabinoid receptor (Oka et al., 2007; Lauckner et al., 2008; Sharir and Abood, 2010). Future investigations will clarify the role of TRPV1 and GPR55 in modulating basal ganglia circuits.

Functional Interactions Between Endocannabinoid and Dopaminergic Systems in the Basal Ganglia

In accordance with its neuroanatomical distribution, functional and behavioral studies have suggested that the endocannabinoid system can act as an indirect modulator of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the basal ganglia.

Behavioral studies

Several influences of cannabinoids on motor activity depend on the cannabinoids influence on the dopaminergic system. Systemic administration of synthetic and endogenous cannabinoids (Δ9-THC, WIN 55,212-2, CP 55,940, or anandamide) characteristically induces inhibition of motor behavior and catalepsy in rodents (Prescott et al., 1992; Crawley et al., 1993; Navarro et al., 1993; Anderson et al., 1995; Romero et al., 1995; de Lago et al., 2004). Moreover, the anandamide transport inhibitor, AM404, or inhibitors of anandamide hydrolysis produce hypokinesia in rats (Compton and Martin, 1997; Gonzalez et al., 1999). These hypokinetic effects can be reversed by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, which in itself causes hyperlocomotion in healthy controls (Compton et al., 1996). In agreement with these observations, mice lacking CB1 receptors exhibit several motor anomalies (Ledent et al., 1999; Zimmer et al., 1999). Although these findings provide evidence for the involvement of CB1-related mechanisms in motor control, other reports demonstrate that also the TRPV1 receptors can mediate effects of certain cannabinoids such as anandamide (de Lago et al., 2004).

It has been hypothesized that the inhibition of motor behavior mediated by cannabinoids could be related to a reduction in dopaminergic circuitry activity. Rotational studies in rats receiving local injections of cannabinoid compounds into the basal ganglia suggest that dopamine-cannabinoid interaction is not a direct mechanism. For instance, cannabinoids increase or decrease motor behavior when locally administered into the direct (Sanudo-Pena et al., 1996, 1998) or indirect pathway, respectively (Sanudo-Pena and Walker, 1997; Miller et al., 1998). Neuroanatomical studies showing that CB1 receptors are not present on dopaminergic neurons or terminals (Julian et al., 2003; Matyas et al., 2006) suggest that CB1-mediated modifications of nigrostriatal dopaminergic circuits are exerted indirectly by modulation of inhibitory or excitatory inputs to the midbrain dopamine neurons. Indeed, cannabinoids are known to dampen both glutamate and GABA transmission in the basal ganglia (Szabo et al., 2000; Gerdeman and Lovinger, 2001; Wallmichrath and Szabo, 2002).

Electrophysiological and neurochemical studies

In vivo electrophysiological studies have shown that cannabinoid agonists increase the action potential firing rate of SNpc neurons (French et al., 1997; Melis et al., 2000; Morera-Herreras et al., 2008). Since CB1 receptors are poorly expressed in SNpc neurons (Julian et al., 2003; Matyas et al., 2006), or even absent, the action of cannabinoids is indirectly exerted on dopaminergic neurons through other nuclei. In line with this, in the SNpr the CB1 receptors are located on subthalamonigral terminals and their activation inhibits glutamate release (Szabo et al., 2000) resulting in a reduction of GABAergic transmission and, consequently, in an increased activity of SNpc cells (Morera-Herreras et al., 2008).

The increased activity of SNpc neurons observed after CB1 receptor activation is in agreement with in vivo microdialysis experiments showing enhanced dopamine release in the striatum after exogenous or endogenous cannabinoid agonists administration (Tanda et al., 1997; Solinas et al., 2006). However, this effect is not mediated locally at the terminal level, but rather involves changes in the firing activity of SNpc neurons, since in vitro studies in striatal slices have shown that CB1 activation has no effect on dopamine release (Kofalvi et al., 2005). Contrary to CB1-mediated mechanisms, the effects of endocannabinoids on dopamine transmission may be mediated by direct mechanisms. Indeed, the endocannabinoid anandamide and some analogs (but not classic cannabinoid as Δ9-THC), acting via postsynaptic TRPV1 receptors, may reduce nigrostriatal dopaminergic cell activity (de Lago et al., 2004). However, other authors have reported an increase of dopamine release after activation of TRPV1 receptors in the SNpc (Marinelli et al., 2003, 2007), although this enhancement may be mediated by TRPV1 receptors located in glutamatergic terminals in the SNpc rather than by receptors located in dopaminergic terminals.

Pathological Implications of the Interaction Between Dopamine and the Endocannabinoid System

As described above, neuroanatomical studies have located cannabinoid receptors in the basal ganglia, and it is widely accepted that the endocannabinoid system influence physiological motor function. These facts predict that pharmacological modulation of the endocannabinoid system may also be beneficial under pathological conditions pertaining to decreased dopamine signaling or the chronic treatment with l-DOPA.

Role of the cannabinoid system in Parkinson’s disease

In Parkinson’s disease (PD), the progression of the neurodegenerative pathology and the appearance of major motor symptoms are related to increased endocannabinoid levels (Pisani et al., 2005, 2010). Several studies have also found increased CB1 receptor levels in the striatum of parkinsonian monkeys and human patients (Lastres-Becker et al., 2001; Van Laere et al., 2012). In rat models of PD, publications supporting increased (Gubellini et al., 2002; Maccarrone et al., 2003; Gonzalez et al., 2005), decreased (Silverdale et al., 2001; Ferrer et al., 2003; Walsh et al., 2010b), or no modification (Romero et al., 2000; Kreitzer and Malenka, 2007) of endocannabinoid tone have been reported. The heterogeneous results obtained in animal models may depend on methodological differences such as the way of inducing parkinsonism or more importantly on the period of recovery after the lesion before performing experiments (Romero et al., 2000).

Studies in animal models and patients of PD have indicated that dopaminergic neuronal degeneration produces an imbalance between the direct and the indirect basal ganglia pathways. This imbalance is manifested as reduced activity of striatal GABAergic neurons in the direct pathway and hyperactivity in the indirect pathway striatal neurons. Moreover, glutamatergic input from the cortex to the striatum is augmented after dopaminergic denervation (Tang et al., 2001; Tseng et al., 2001; Gubellini et al., 2002; Mallet et al., 2006). Within the basal ganglia, CB1 receptors are principally expressed on presynaptic cortical glutamatergic terminals and presynaptic striatal GABAergic terminals (Benarroch, 2007). The activation of CB1 receptors reduces the glutamate release from the cortex to the striatum (Gerdeman and Lovinger, 2001; Gubellini et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2003) and GABA release to the SNpr (Wallmichrath and Szabo, 2002). In addition, endocannabinoids and CB1 receptors play an important physiological role in the long- and short-term regulation of the synaptic transmission in the basal ganglia shaping the striatal output and therefore modulating motor activities. The two classic forms of long-term synaptic plasticity, long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTD) are expressed at corticostriatal synapses and abolished in animal models of PD (Centonze et al., 1999; Picconi et al., 2005; Calabresi et al., 2007; Kreitzer and Malenka, 2007). Using different LTD induction paradigms it has been described that this form of plasticity is mostly controlled by endocannabinoids (Shen et al., 2008; Lovinger, 2010). Although probably other mechanisms are also involved in the dopaminergic control of striatal plasticity, pharmacological manipulation of the endocannabinoid system under parkinsonian conditions has been proved not only to rescue LTD in striatum but also to improve the motor deficits evident after dopaminergic denervation (Kreitzer and Malenka, 2007).

In line with this, behavioral studies have shown that modulation of the endocannabinoid system can have a therapeutic impact in animal models of PD. Behavioral changes caused by the induction of parkinsonism in rats have been improved by the administration of CB1 receptor antagonists both in unilateral and bilateral PD models in rodents (Fernandez-Espejo et al., 2005; Gonzalez et al., 2006; Kelsey et al., 2009). In MPTP-lesioned marmosets, CB1 antagonist administration increased locomotor activity but failed to improve bradykinesia or posture (van der Stelt et al., 2005). On the other hand, co-administration of l-DOPA with CB1 antagonists added a positive improvement of the motor symptoms assigned to the antiparkinsonian drug in parkinsonian animals (Kelsey et al., 2009). The latter data suggest that combined therapy with antiparkinsonian drugs and cannabinoid antagonists may permit a reduction of l-DOPA dose and therefore, delay the emergence of the motor side effects induced by the chronic treatment with l-DOPA.

The benefit of cannabinoids in PD is not limited to the symptomatic amelioration. Lately, several reports have revealed interesting neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of these drugs in cell cultures and animal models of PD (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; Garcia-Arencibia et al., 2007; Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2011; Jeon et al., 2011; Carroll et al., 2012). Although CB1 receptor-mediated effects cannot be excluded, some authors argue that CB1 receptors may have a minimal implication in neuroprotection (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2007; Price et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2011). It seems plausible that neuroprotection is principally mediated by the antioxidant effect of cannabinoids and CB1 receptor-independent properties (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; Garcia-Arencibia et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2012), while in parallel, activation of CB2 receptors in astrocytes and microglial cells is responsible for the observed anti-inflammatory effect. Although the exact mechanisms should be further investigated, cannabinoid receptor modulation can be potentially useful for protecting dopaminergic neurons from progressive neurodegeneration in PD.

Implication of the cannabinoid system in l-DOPA induced dyskinesia

The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system as modulator of neurotransmission in the basal ganglia identifies it as a potential pharmacological target for treating motor complications derived from the chronic treatment with l-DOPA. l-DOPA induced dyskinesia (LID) constitute one of the most disabling complications derived from the long-term therapy with l-DOPA affecting up to 40% of PD patients after 5 years of treatment (Ahlskog and Muenter, 2001). Cannabinoid agonists could exert antidyskinetic effect by regulating glutamatergic release in the striatum and/or by re-establishing endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity affected by dopaminergic denervation. In this sense, pharmacological agents with antidyskinetic properties such as serotonergic 5-HT1B agonists are able to ameliorate the motor complications by depressing the glutamatergic corticostriatal transmission (Mathur et al., 2011).

Cannabinoid agents have been proposed as promising tools for treating LID, however, different studies in animal models and patients show certain discrepancies. Administration of cannabinoid agonists to parkinsonian rats receiving chronic l-DOPA treatment attenuated LID via CB1-related mechanisms (Ferrer et al., 2003; Morgese et al., 2007; Martinez et al., 2012) and genetic deletion of CB1 receptors prevented the development of severe dyskinetic movements in mice (Perez-Rial et al., 2011). Although the cited studies do not report any reduction of the efficacy of l-DOPA to improve the motor performance, a recent publication suggests that the antidyskinetic effect of cannabinoid agonists seem to be based on their general motor suppressant (Walsh et al., 2010a). In MPTP-lesioned monkeys and PD patients contradictory results have been found since CB1 receptor activation (Silverdale et al., 2001; Fox et al., 2002) or blockage (van der Stelt et al., 2005) ameliorated LID. Other studies in patients have failed to find any correlation between CB1 receptor expression and severity of dyskinesia (van der Stelt et al., 2005) or attribute any positive effect of cannabinoid agent administration in LID (Carroll et al., 2004; Mesnage et al., 2004).

Taken together, changes in the cannabinoid system are observed after dopaminergic denervation and manipulation of this system has proved to have beneficial effects on parkinsonian symptoms in animal models and PD patients. However, the putative role of cannabinoids in LID is still a matter of controversy. The complex localization of the cannabinoid receptors at different sites in the basal ganglia circuits may contribute to the paradoxical observed effects. Further investigations are needed to clarify the role of the cannabinoid system in LID.

In conclusion, the endocannabinoid system modulates nigrostriatal dopamine transmission both via direct and indirect mechanisms. This system has an important role in dopamine-related movement disorders, as PD, and represents a framework for novel therapeutic approaches in the future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jan Tonnesen for careful reading and pertinent comments. Financial support UFI 11/32.

References

- Ahlskog J. E., Muenter M. D. (2001). Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov. Disord. 16, 448–458 10.1002/mds.1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L. A., Anderson J. J., Chase T. N., Walters J. R. (1995). The cannabinoid agonists WIN 55,212-2 and CP 55,940 attenuate rotational behavior induced by a dopamine D1 but not a D2 agonist in rats with unilateral lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway. Brain Res. 691, 106–114 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00645-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood B. K., Mackie K. (2010). CB2: a cannabinoid receptor with an identity crisis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 467–479 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00729.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch E. (2007). Endocannabinoids in basal ganglia circuits: implications for Parkinson disease. Neurology 69, 306–309 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275537.71623.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotchie J. M. (2003). CB1 cannabinoid receptor signalling in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 3, 54–61 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. M., Brotchie J. M., Fitzjohn S. M. (2003). Cannabinoids decrease corticostriatal synaptic transmission via an effect on glutamate uptake. J. Neurosci. 23, 11073–11077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P., Picconi B., Tozzi A., Di Filippo M. (2007). Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 30, 211–219 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. B., Bain P. G., Teare L., Liu X., Joint C., Wroath C., Parkin S. G., Fox P., Wright D., Hobart J., Zajicek J. P. (2004). Cannabis for dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Neurology 63, 1245–1250 10.1212/01.WNL.0000140288.48796.8E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. B., Zeissler M. L., Hanemann C. O., Zajicek J. P. (2012). Delta(9) -THC exerts a direct neuroprotective effect in a human cell culture model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 10.111/J.1365-2990.2011.01248.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh D. J., Chesler A. T., Jackson A. C., Sigal Y. M., Yamanaka H., Grant R., O’Donnell D., Nicoll R. A., Shah N. M., Julius D., Basbaum A. I. (2011). Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J. Neurosci. 31, 5067–5077 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D., Gubellini P., Picconi B., Calabresi P., Giacomini P., Bernardi G. (1999). Unilateral dopamine denervation blocks corticostriatal LTP. J. Neurophysiol. 82, 3575–3579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y. C., Bok E., Huh S. H., Park J. Y., Yoon S. H., Kim S. R., Kim Y. S., Maeng S., Park S. H., Jin B. K. (2011). Cannabinoid receptor type 1 protects nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons against MPTP neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglial activation. J. Immunol. 187, 6508–6517 10.4049/jimmunol.1102435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D. R., Aceto M. D., Lowe J., Martin B. R. (1996). In vivo characterization of a specific cannabinoid receptor antagonist (SR141716A): inhibition of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced responses and apparent agonist activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 277, 586–594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D. R., Martin B. R. (1997). The effect of the enzyme inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride on the pharmacological effect of anandamide in the mouse model of cannabimimetic activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283, 1138–1143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J. N., Corwin R. L., Robinson J. K., Felder C. C., Devane W. A., Axelrod J. (1993). Anandamide, an endogenous ligand of the cannabinoid receptor, induces hypomotility and hypothermia in vivo in rodents. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 46, 967–972 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90230-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L., De Petrocellis L., Pryce G., Baker D., Guglielmotti V., Di Marzo V. (2006). Immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid type 1 and vanilloid transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in the mouse brain. Neuroscience 139, 1405–1415 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lago E., De Miguel R., Lastres-Becker I., Ramos J. A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2004). Involvement of vanilloid-like receptors in the effects of anandamide on motor behavior and nigrostriatal dopaminergic activity: in vivo and in vitro evidence. Brain Res. 1007, 152–159 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane W. A., Hanus L., Breuer A., Pertwee R. G., Stevenson L. A., Griffin G., Gibson D., Mandelbaum A., Etinger A., Mechoulam R. (1992). Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258, 1946–1949 10.1126/science.1470919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V., Fontana A., Cadas H., Schinelli S., Cimino G., Schwartz J. C., Piomelli D. (1994). Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature 372, 686–691 10.1038/372686a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V., Melck D., Bisogno T., De Petrocellis L. (1998). Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends Neurosci. 21, 521–528 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01283-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Espejo E., Caraballo I., De Fonseca F. R., El Banoua F., Ferrer B., Flores J. A., Galan-Rodriguez B. (2005). Cannabinoid CB1 antagonists possess antiparkinsonian efficacy only in rats with very severe nigral lesion in experimental parkinsonism. Neurobiol. Dis. 18, 591–601 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2009). The endocannabinoid system as a target for the treatment of motor dysfunction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 156, 1029–1040 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J., Moreno-Martet M., Rodriguez-Cueto C., Palomo-Garo C., Gomez-Canas M., Valdeolivas S., Guaza C., Romero J., Guzman M., Mechoulam R., Ramos J. A. (2011). Prospects for cannabinoid therapies in basal ganglia disorders. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 1365–1378 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01365.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J., Romero J., Velasco G., Tolon R. M., Ramos J. A., Guzman M. (2007). Cannabinoid CB2 receptor: a new target for controlling neural cell survival? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 39–45 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer B., Asbrock N., Kathuria S., Piomelli D., Giuffrida A. (2003). Effects of levodopa on endocannabinoid levels in rat basal ganglia: implications for the treatment of levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1607–1614 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. H., Henry B., Hill M., Crossman A., Brotchie J. (2002). Stimulation of cannabinoid receptors reduces levodopa-induced dyskinesia in the MPTP-lesioned nonhuman primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 17, 1180–1187 10.1002/mds.10289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French E. D., Dillon K., Wu X. (1997). Cannabinoids excite dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmentum and substantia nigra. Neuroreport 8, 649–652 10.1097/00001756-199702100-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Arencibia M., Gonzalez S., De Lago E., Ramos J. A., Mechoulam R., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2007). Evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: importance of antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent properties. Brain Res. 1134, 162–170 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman G., Lovinger D. M. (2001). CB1 cannabinoid receptor inhibits synaptic release of glutamate in rat dorsolateral striatum. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 468–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida A., Parsons L. H., Kerr T. M., Rodriguez de Fonseca F., Navarro M., Piomelli D. (1999). Dopamine activation of endogenous cannabinoid signaling in dorsal striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 358–363 10.1038/7268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass M., Felder C. C. (1997). Concurrent stimulation of cannabinoid CB1 and dopamine D2 receptors augments cAMP accumulation in striatal neurons: evidence for a Gs linkage to the CB1 receptor. J. Neurosci. 17, 5327–5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. P., Onaivi E. S., Ishiguro H., Liu Q. R., Tagliaferro P. A., Brusco A., Uhl G. R. (2006). Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res. 1071, 10–23 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S., Mena M. A., Lastres-Becker I., Serrano A., De Yebenes J. G., Ramos J. A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2005). Cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in the basal ganglia and motor response to activation or blockade of these receptors in parkin-null mice. Brain Res. 1046, 195–206 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S., Romero J., De Miguel R., Lastres-Becker I., Villanua M. A., Makriyannis A., Ramos J. A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. J. (1999). Extrapyramidal and neuroendocrine effects of AM404, an inhibitor of the carrier-mediated transport of anandamide. Life Sci. 65, 327–336 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00251-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S., Scorticati C., Garcia-Arencibia M., De Miguel R., Ramos J. A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2006). Effects of rimonabant, a selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1073–1074, 209–219. 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P., Picconi B., Bari M., Battista N., Calabresi P., Centonze D., Bernardi G., Finazzi-Agro A., Maccarrone M. (2002). Experimental parkinsonism alters endocannabinoid degradation: implications for striatal glutamatergic transmission. J. Neurosci. 22, 6900–6907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M., Lynn A. B., de Costa B. R., Richfield E. K. (1991). Neuronal localization of cannabinoid receptors in the basal ganglia of the rat. Brain Res. 547, 267–274 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90970-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M., Lynn A. B., Little M. D., Johnson M. R., Melvin L. S., de Costa B. R., Rice K. C. (1990). Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 1932–1936 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon P., Yang S., Jeong H., Kim H. (2011). Cannabinoid receptor agonist protects cultured dopaminergic neurons from the death by the proteasomal dysfunction. Anat. Cell Biol. 44, 135–142 10.5115/acb.2011.44.2.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian M. D., Martin A. B., Cuellar B., Rodriguez de Fonseca F., Navarro M., Moratalla R., Garcia-Segura L. M. (2003). Neuroanatomical relationship between type 1 cannabinoid receptors and dopaminergic systems in the rat basal ganglia. Neuroscience 119, 309–318 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00070-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearn C. S., Blake-Palmer K., Daniel E., Mackie K., Glass M. (2005). Concurrent stimulation of cannabinoid CB1 and dopamine D2 receptors enhances heterodimer formation: a mechanism for receptor cross-talk? Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 1697–1704 10.1124/mol.104.006882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey J. E., Harris O., Cassin J. (2009). The CB(1) antagonist rimonabant is adjunctively therapeutic as well as monotherapeutic in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 203, 304–307 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofalvi A., Rodrigues R. J., Ledent C., Mackie K., Vizi E. S., Cunha R. A., Sperlagh B. (2005). Involvement of cannabinoid receptors in the regulation of neurotransmitter release in the rodent striatum: a combined immunochemical and pharmacological analysis. J. Neurosci. 25, 2874–2884 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4232-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer A. C., Malenka R. C. (2007). Endocannabinoid-mediated rescue of striatal LTD and motor deficits in Parkinson’s disease models. Nature 445, 643–647 10.1038/nature05506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I., Cebeira M., de Ceballos M. L., Zeng B. Y., Jenner P., Ramos J. A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. J. (2001). Increased cannabinoid CB1 receptor binding and activation of GTP-binding proteins in the basal ganglia of patients with Parkinson’s syndrome and of MPTP-treated marmosets. Eur. J. Neurosci. 14, 1827–1832 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I., Molina-Holgado F., Ramos J. A., Mechoulam R., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2005). Cannabinoids provide neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in vivo and in vitro: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 19, 96–107 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauckner J. E., Jensen J. B., Chen H. Y., Lu H. C., Hille B., Mackie K. (2008). GPR55 is a cannabinoid receptor that increases intracellular calcium and inhibits M current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2699–2704 10.1073/pnas.0711278105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C., Valverde O., Cossu G., Petitet F., Aubert J. F., Beslot F., Bohme G. A., Imperato A., Pedrazzini T., Roques B. P., Vassart G., Fratta W., Parmentier M. (1999). Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science 283, 401–404 10.1126/science.283.5400.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovinger D. M. (2010). Neurotransmitter roles in synaptic modulation, plasticity and learning in the dorsal striatum. Neuropharmacology 58, 951–961 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M., Gubellini P., Bari M., Picconi B., Battista N., Centonze D., Bernardi G., Finazzi-Agro A., Calabresi P. (2003). Levodopa treatment reverses endocannabinoid system abnormalities in experimental parkinsonism. J. Neurochem. 85, 1018–1025 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. (2005). Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 168, 299–325 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. (2008). Cannabinoid receptors: where they are and what they do. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20 (Suppl. 1), 10–14 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailleux P., Vanderhaeghen J. J. (1992). Localization of cannabinoid receptor in the human developing and adult basal ganglia. Higher levels in the striatonigral neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 148, 173–176 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90832-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N., Ballion B., Le Moine C., Gonon F. (2006). Cortical inputs and GABA interneurons imbalance projection neurons in the striatum of parkinsonian rats. J. Neurosci. 26, 3875–3884 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcellino D., Carriba P., Filip M., Borgkvist A., Frankowska M., Bellido I., Tanganelli S., Muller C. E., Fisone G., Lluis C., Agnati L. F., Franco R., Fuxe K. (2008). Antagonistic cannabinoid CB1/dopamine D2 receptor interactions in striatal CB1/D2 heteromers. A combined neurochemical and behavioral analysis. Neuropharmacology 54, 815–823 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S., di Marzo V., Berretta N., Matias I., Maccarrone M., Bernardi G., Mercuri N. B. (2003). Presynaptic facilitation of glutamatergic synapses to dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra by endogenous stimulation of vanilloid receptors. J. Neurosci. 23, 3136–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S., Di Marzo V., Florenzano F., Fezza F., Viscomi M. T., Van Der Stelt M., Bernardi G., Molinari M., MacCarrone M., Mercuri N. B. (2007). N-arachidonoyl-dopamine tunes synaptic transmission onto dopaminergic neurons by activating both cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 298–308 10.1038/sj.npp.1301118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. B., Fernandez-Espejo E., Ferrer B., Gorriti M. A., Bilbao A., Navarro M., Rodriguez de Fonseca F., Moratalla R. (2008). Expression and function of CB1 receptor in the rat striatum: localization and effects on D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-mediated motor behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 1667–1679 10.1038/sj.npp.1301490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A., Macheda T., Morgese M. G., Trabace L., Giuffrida A. (2012). The cannabinoid agonist WIN55212-2 decreases L-DOPA-induced PKA activation and dyskinetic behavior in 6-OHDA-treated rats. Neurosci. Res. 72, 236–242 10.1016/j.neures.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur B. N., Capik N. A., Alvarez V. A., Lovinger D. M. (2011). Serotonin induces long-term depression at corticostriatal synapses. J. Neurosci. 31, 7402–7411 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6250-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda L. A., Lolait S. J., Brownstein M. J., Young A. C., Bonner T. I. (1990). Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346, 561–564 10.1038/346561a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyas F., Yanovsky Y., Mackie K., Kelsch W., Misgeld U., Freund T. F. (2006). Subcellular localization of type 1 cannabinoid receptors in the rat basal ganglia. Neuroscience 137, 337–361 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R., Ben-Shabat S., Hanus L., Ligumsky M., Kaminski N. E., Schatz A. R., Gopher A., Almog S., Martin B. R., Compton D. R., Pertwee R. G., Griffin G., Bayewitch M., Barg J., Vogel Z. (1995). Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 50, 83–90 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis M., Gessa G. L., Diana M. (2000). Different mechanisms for dopaminergic excitation induced by opiates and cannabinoids in the rat midbrain. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 24, 993–1006 10.1016/S0278-5846(00)00119-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschler J. P., Howlett A. C. (2001). Signal transduction interactions between CB1 cannabinoid and dopamine receptors in the rat and monkey striatum. Neuropharmacology 40, 918–926 10.1016/S0028-3908(01)00012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage V., Houeto J. L., Bonnet A. M., Clavier I., Arnulf I., Cattelin F., Le Fur G., Damier P., Welter M. L., Agid Y. (2004). Neurokinin B, neurotensin, and cannabinoid receptor antagonists and Parkinson disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 27, 108–110 10.1097/00002826-200405000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E., Toth Z. E., Cortright D. N., Arzubi M. K., Krause J. E., Elde R., Guo A., Blumberg P. M., Szallasi A. (2000). Distribution of mRNA for vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1), and VR1-like immunoreactivity, in the central nervous system of the rat and human. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3655–3660 10.1073/pnas.060496197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micale V., Cristino L., Tamburella A., Petrosino S., Leggio G. M., Drago F., di Marzo V. (2009). Anxiolytic effects in mice of a dual blocker of fatty acid amide hydrolase and transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channels. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 593–606 10.1038/npp.2008.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. S., Sanudo-Pena M. C., Walker J. M. (1998). Ipsilateral turning behavior induced by unilateral microinjections of a cannabinoid into the rat subthalamic nucleus. Brain Res. 793, 7–11 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01475-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera-Herreras T., Ruiz-Ortega J. A., Gomez-Urquijo S., Ugedo L. (2008). Involvement of subthalamic nucleus in the stimulatory effect of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol on dopaminergic neurons. Neuroscience 151, 817–823 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgese M. G., Cassano T., Cuomo V., Giuffrida A. (2007). Anti-dyskinetic effects of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: role of CB(1) and TRPV1 receptors. Exp. Neurol. 208, 110–119 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S., Thomas K. L., Abu-Shaar M. (1993). Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 365, 61–65 10.1038/365061a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M., Fernandez-Ruiz J. J., De Miguel R., Hernandez M. L., Cebeira M., Ramos J. A. (1993). Motor disturbances induced by an acute dose of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol: possible involvement of nigrostriatal dopaminergic alterations. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 45, 291–298 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90241-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola S. M., Surmeier J., Malenka R. C. (2000). Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 185–215 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor W. T. (1998). Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia as studied by dual-probe microdialysis. Nucl. Med. Biol. 25, 743–746 10.1016/S0969-8051(98)00066-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka S., Nakajima K., Yamashita A., Kishimoto S., Sugiura T. (2007). Identification of GPR55 as a lysophosphatidylinositol receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362, 928–934 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onn S. P., West A. R., Grace A. A. (2000). Dopamine-mediated regulation of striatal neuronal and network interactions. Trends Neurosci. 23, S48–S56 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01500-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M. L., Graybiel A. M., David J. C., Robertson H. A. (1992). D1-like and D2-like dopamine receptors synergistically activate rotation and c-fos expression in the dopamine-depleted striatum in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 12, 3729–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rial S., Garcia-Gutierrez M. S., Molina J. A., Perez-Nievas B. G., Ledent C., Leiva C., Leza J. C., Manzanares J. (2011). Increased vulnerability to 6-hydroxydopamine lesion and reduced development of dyskinesias in mice lacking CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 631–645 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picconi B., Pisani A., Barone I., Bonsi P., Centonze D., Bernardi G., Calabresi P. (2005). Pathological synaptic plasticity in the striatum: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology 26, 779–783 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A., Fezza F., Galati S., Battista N., Napolitano S., Finazzi-Agro A., Bernardi G., Brusa L., Pierantozzi M., Stanzione P., Maccarrone M. (2005). High endogenous cannabinoid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Ann. Neurol. 57, 777–779 10.1002/ana.20462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani V., Moschella V., Bari M., Fezza F., Galati S., Bernardi G., Stanzione P., Pisani A., Maccarrone M. (2010). Dynamic changes of anandamide in the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov. Disord. 25, 920–924 10.1002/mds.23014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott W. R., Gold L. H., Martin B. R. (1992). Evidence for separate neuronal mechanisms for the discriminative stimulus and catalepsy induced by delta 9-THC in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 107, 117–124 10.1007/BF02244975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D. A., Martinez A. A., Seillier A., Koek W., Acosta Y., Fernandez E., Strong R., Lutz B., Marsicano G., Roberts J. L., Giuffrida A. (2009). WIN55,212-2, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, protects against nigrostriatal cell loss in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 2177–2186 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06786.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero J., Berrendero F., Perez-Rosado A., Manzanares J., Rojo A., Fernandez-Ruiz J. J., de Yebenes J. G., Ramos J. A. (2000). Unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons increased CB1 receptor mRNA levels in the caudate-putamen. Life Sci. 66, 485–494 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00618-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero J., Garcia L., Cebeira M., Zadrozny D., Fernandez-Ruiz J. J., Ramos J. A. (1995). The endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand, anandamide, inhibits the motor behavior: role of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Life Sci. 56, 2033–2040 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00186-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg E., Larsson N., Sjogren S., Hjorth S., Hermansson N. O., Leonova J., Elebring T., Nilsson K., Drmota T., Greasley P. J. (2007). The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 152, 1092–1101 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo-Pena M. C., Force M., Tsou K., Miller A. S., Walker J. M. (1998). Effects of intrastriatal cannabinoids on rotational behavior in rats: interactions with the dopaminergic system. Synapse 30, 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo-Pena M. C., Patrick S. L., Patrick R. L., Walker J. M. (1996). Effects of intranigral cannabinoids on rotational behavior in rats: interactions with the dopaminergic system. Neurosci. Lett. 206, 21–24 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12436-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo-Pena M. C., Walker J. M. (1997). Role of the subthalamic nucleus in cannabinoid actions in the substantia nigra of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 77, 1635–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawzdargo M., Nguyen T., Lee D. K., Lynch K. R., Cheng R., Heng H. H., George S. R., O’Dowd B. F. (1999). Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, PsiGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 64, 193–198 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharir H., Abood M. E. (2010). Pharmacological characterization of GPR55, a putative cannabinoid receptor. Pharmacol. Ther. 126, 301–313 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Flajolet M., Greengard P., Surmeier D. J. (2008). Dichotomous dopaminergic control of striatal synaptic plasticity. Science 321, 848–851 10.1126/science.1160575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverdale M. A., Mcguire S., Mcinnes A., Crossman A. R., Brotchie J. M. (2001). Striatal cannabinoid CB1 receptor mRNA expression is decreased in the reserpine-treated rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 169, 400–406 10.1006/exnr.2001.7649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M., Justinova Z., Goldberg S. R., Tanda G. (2006). Anandamide administration alone and after inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) increases dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens shell in rats. J. Neurochem. 98, 408–419 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson P., Fredholm B. B., Bloch B., Le Moine C. (2000). Co-stimulation of D(1)/D(5) and D(2) dopamine receptors leads to an increase in c-fos messenger RNA in cholinergic interneurons and a redistribution of c-fos messenger RNA in striatal projection neurons. Neuroscience 98, 749–757 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00155-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo B., Wallmichrath I., Mathonia P., Pfreundtner C. (2000). Cannabinoids inhibit excitatory neurotransmission in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. Neuroscience 97, 89–97 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G., Pontieri F. E., Di Chiara G. (1997). Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common mu1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science 276, 2048–2050 10.1126/science.276.5321.2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K., Low M. J., Grandy D. K., Lovinger D. M. (2001). Dopamine-dependent synaptic plasticity in striatum during in vivo development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1255–1260 10.1073/pnas.121046998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng K. Y., Kasanetz F., Kargieman L., Riquelme L. A., Murer M. G. (2001). Cortical slow oscillatory activity is reflected in the membrane potential and spike trains of striatal neurons in rats with chronic nigrostriatal lesions. J. Neurosci. 21, 6430–6439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K., Brown S., Sanudo-Pena M. C., Mackie K., Walker J. M. (1998). Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience 83, 393–411 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00436-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Stelt M., Di Marzo V. (2003). The endocannabinoid system in the basal ganglia and in the mesolimbic reward system: implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 480, 133–150 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Stelt M., Fox S. H., Hill M., Crossman A. R., Petrosino S., di Marzo V., Brotchie J. M. (2005). A role for endocannabinoids in the generation of parkinsonism and levodopa-induced dyskinesia in MPTP-lesioned non-human primate models of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 19, 1140–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere K., Casteels C., Lunskens S., Goffin K., Grachev I. D., Bormans G., Vandenberghe W. (2012). Regional changes in type 1 cannabinoid receptor availability in Parkinson’s disease in vivo. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 620e621–620.e628. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle M. D., Duncan M., Kingsley P. J., Mouihate A., Urbani P., Mackie K., Stella N., Makriyannis A., Piomelli D., Davison J. S., Marnett L. J., di Marzo V., Pittman Q. J., Patel K. D., Sharkey K. A. (2005). Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science 310, 329–332 10.1126/science.1115740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallmichrath I., Szabo B. (2002). Cannabinoids inhibit striatonigral GABAergic neurotransmission in the mouse. Neuroscience 113, 671–682 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S., Gorman A. M., Finn D. P., Dowd E. (2010a). The effects of cannabinoid drugs on abnormal involuntary movements in dyskinetic and non-dyskinetic 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rats. Brain Res. 1363, 40–48 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S., Mnich K., Mackie K., Gorman A. M., Finn D. P., Dowd E. (2010b). Loss of cannabinoid CB1 receptor expression in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced nigrostriatal terminal lesion model of Parkinson’s disease in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 81, 543–548 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A., Zimmer A. M., Hohmann A. G., Herkenham M., Bonner T. I. (1999). Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5780–5785 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]