Abstract

Polymorphisms in genes involved in folate metabolism may modulate the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), but data from published studies are conflicting. The current meta-analysis was performed to address a more accurate estimation. A total of 41 (17,552 cases and 26,238 controls), 24(8,263 cases and 12,033 controls), 12(3,758 cases and 5,646 controls), and 13 (5,511 cases and 7,265 controls) studies were finally included for the association between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T and A1289C, methione synthase reductase (MTRR) A66G, methionine synthase (MTR) A2756G polymorphisms and the risk of CRC, respectively. The data showed that the MTHFR 677T allele was significantly associated with reduced risk of CRC (OR = 0.93, 95%CI 0.90-0.96), while the MTRR 66G allele was significantly associated with increased risk of CRC (OR = 1.11, 95%CI 1.01-1.18). Sub-group analysis by ethnicity revealed that MTHFR C677T polymorphism was significantly associated with reduced risk of CRC in Asians (OR = 0.80, 95%CI 0.72-0.89) and Caucasians (OR = 0.84, 95%CI 0.76-0.93) in recessive genetic model, while the MTRR 66GG genotype was found to significantly increase the risk of CRC in Caucasians (GG vs. AA: OR = 1.18, 95%CI 1.03-1.36). No significant association was found between MTHFR A1298C and MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the risk of CRC. Cumulative meta-analysis showed no particular time trend existed in the summary estimate. Probability of publication bias was low across all comparisons illustrated by the funnel plots and Egger's test. Collectively, this meta-analysis suggested that MTHFR 677T allele might provide protection against CRC in worldwide populations, while MTRR 66G allele might increase the risk of CRC in Caucasians. Since potential confounders could not be ruled out completely, further studies were needed to confirm these results.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, Methione synthase reductase, Methionine synthase, Folate.

Introduction

Folate is critical to one-carbon metabolism, acting as a coenzyme in nucleotide synthesis and the methylation of DNA, histones, and other proteins 1. Accumulating evidence supports the important roles of folate in the etiology of colorectal cancer (CRC). Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), methionine synthase (MTR), and methione synthase reductase (MTRR) are key enzymes involved in folate metabolism, and play essential roles in DNA synthesis, repair, and methylation. The abnormalities in these processes have been consistently observed in CRC patients, and are implicated in the pathogenesis of CRC 2.

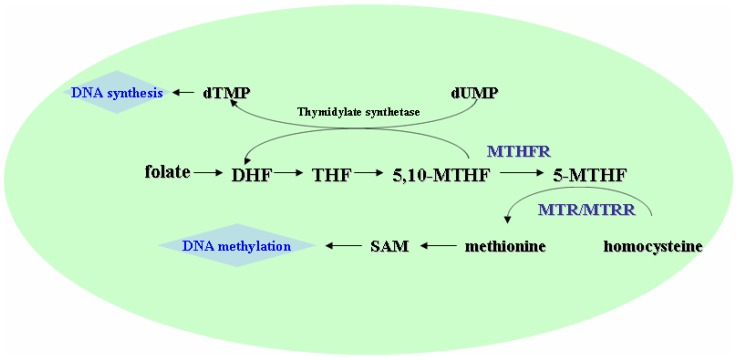

MTHFR could convert 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-MTHF), the major intracellular form of folate, to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), the major circulatory form of folate in the body (Fig.1) 3. The 5-MTHF donates a methyl group to homocysteine in the generation of methionine, which then converts to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl-group donor involved in methylation reaction including DNA methylation 3, 4. The methylation of homocysteine to methionine is catalyzed by MTR using vitamin B12 as a cofactor, in which the MTR may become inactivated due to the oxidation of vitamin B12 cofactor. MTRR could catalyze reductive methylation of vitamin B12 by using SAM as a methyl donor, leading to the activation of MTR 5, 6.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the folate, methionine, and homocysteine metabolism. DHF, dihydrotetrafolic acid; THF, tetrahydrofolic acid; 5,10-MTHF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; 5-MTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolat; SAM, S- adenosylmethionine; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTR, methionine synthase; MTRR, methione synthase reductase.

Two common functional polymorphisms in the MTHFR gene, C677T (rs1801133) and A1298C (rs1801131), have been reported. The C677T polymorphism in exon 4 of MTHFR gene leads to the amino acid substitution of alanine by valine at codon 222 (A222V) which could cause a thermolabile enzyme with lower activity 7. Homozygotes TT have approximately 30% of normal enzyme activity, whereas heterozygotes CT have approximately 60% of the normal enzyme activity, hence they tend to accumulate 5,10-methylene-THF displacing the reaction towards the DNA synthesis at the expense of the pool of methyl donors 8. Another MTHFR polymorphism, A1298C polymorphism (rs1801131) in exon 7, could result in the substitution of glutamate by alanine 9. This polymorphism could lead to a decrease of 40% in enzyme activity of the variant genotype 10. MTR A2756G (rs1805087) gene polymorphism was initially thought to be associated with lower enzyme activity, leading to homocysteine elevation and DNA hypomethylation 11. However, some other studies found a modest inverse association between 2576GG polymorphism and homocysteine levels, indicating an increased enzymatic activity of the variant genotype 12. For the MTRR, the most common polymorphism is an isoleucine-to-methionine change at position 22 A66G (A66G; rs1801394), and it has demonstrated that 66GG genotype was inversely associated with plasma homocysteine levels 13.

Considering the functional effects of the polymorphisms of these enzymes, it is expected that these gene polymorphisms may be associated with the CRC risks, and thus a large number of epidemiological studies have been conducted trying to clarify the above question, but obtain conflicting results. For example, some studies show a protective effect of 677TT variant against CRC 4, 14, 15, while others found no association and even deleterious effects 16-18. Similarly, the association between the other three gene polymorphisms and the risk of CRC also remains controversial. Race, life style, and the pattern of diet may have introduced variability into the test of genetic susceptibility to disease in the different studies 19. To clarify these issues, we performed a meta-analysis from all eligible studies, in order to provide more accurate estimate of the association of the above four gene polymorphisms and the risk of CRC.

Materials and methods

Literature and search strategy

A computerized literature search was conducted for the relevant available studies published in English from 3 databases including PubMed (1950 to 2012), ISI web of science (1975 to 2012), and Embase (1966 to 2012). The search strategy to identify all possible studies involved use of the combinations of the following key words: (“one-carbon metabolism” or “methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase” or “MTHFR” or “methionine synthase” or “MTR” or “methione synthase reductase” or “MTRR”) and (“colorectal” or “colon” or “rectal”) and (“cancer” or “carcinoma” or “adenocarcinoma”). The reference lists of review articles, clinical trials, and meta-analyses, were also hand-searched for the collection of other relevant studies. If more than one article were published using the same case series, only the study with largest sample size was selected. The literature search was updated on Feb 28, 2012.

Inclusion criteria

The studies included must meet the following criteria: (1) evaluating the association between MTHFR C677T or MTHFR A1289C or MTRR A66G or MTR A2756G polymorphism and the risk of CRC; (2) case-control or cohort design; (3) providing sufficient data for calculation of odds ratio (OR) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI). When genotype frequencies and OR with 95%CI were all not available, authors were contacted to request the relevant information. All identified studies were carefully reviewed independently by two investigators to determine whether an individual study was eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two investigators who reached a consensus on all of the items. The following information was extracted from each study: (1) name of the first author; (2) year of publication; (3) country of origin; (4) ethnicity of the study population; (5) source of control subjects; (6) numbers of cases and controls; and (7) numbers of genotypes in cases and controls.

Statistical analysis

We use χ2 analysis with exact probability to test departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for the genotype distribution. The association of four gene polymorphisms with CRC risk was estimated by calculating pooled ORs and 95% CI. The significance of the pooled effect size was determined by Z test. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Q test as well as the I2statistic, which was documented for the percentage of the observed between-study variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance 20. The DerSimonian and Laird random effect model (REM) was used as the pooling method when I2 > 50%, otherwise, the Mantel-Haenszel fixed effect model (FEM) was considered to be the appropriate choice 20. Subgroup analysis stratified by ethnicity was only considered for Asians and Caucasians as small numbers of studies were conducted in other ethnic groups. Cumulative meta-analysis was performed to assess whether the combined estimate changed in the same direction over time 21. Influential analysis was undertaken by removing an individual study each time to check whether any of single study could bias the overall estimate 22. An individual study was suspected of excessive influence, if the point estimate of its omitted analysis lies outside of the 95%CI of the combined analysis. Begg's funnel plots and Egger's regression test were undertaken to assess the potential publication bias 23. Probability less than 0.05 was judged significant except for the I2 statistic. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Characteristics of studies

A total of 41 (17,552 cases and 26,238 controls), 24(8,263 cases and 12,033 controls), 12(3,758 cases and 5,646 controls), and 13 (5,511 cases and 7,265 controls) studies were finally included in the meta-analyses for the association between the MTHFR C677T, MTHFR A1298C, MTRR A66G, MTR A2756G and the risk of CRC, respectively. Among these studies, Keku et al. provided data on two ethnicities 24, while Le Marchand et al. reported on three separate populations25, and thus each subpopulation in these two studies were treated as a separate one. All the included studies used blood samples for the extraction of DNA, except for the study by Shannon et al. in which frozen tissues samples were used 26. Genotyping was performed by using PCR-RFLP, real-time PCR, or Taqman SNP genotyping assay. These studies were performed in a wide range of geographical settings leading to a diversity of racial groups. For the MTHFR C677T, 20 studies recruited Caucasians 4, 14-16, 18, 24-38; 11 studies examined individuals of Asian descent 25, 39-48; the remaining 10 studies were on Indians, Africans, Hawaiian, or mixed population. For the MTHFR A1298C, MTRR A66G, MTR A2756G analyses, 12, 6, and 7 studies were conducted in Caucasians, respectively, while 5, 3, and 3 studies were in Asians. Genotype distributions in the controls of all studies were in HWE except for 8 studies for MTHFR C677T polymorphism 29, 31, 37, 40, 44, 48-50, 4 studies for A1298C polymorphism 14, 17, 28, 41, 1 study for MTRR A66G polymorphism 47, and 1 study for MTR A2756G polymorphism 17. The detailed characteristics of the included studies were shown in the supplementary Table 1.

Quantitative data synthesis

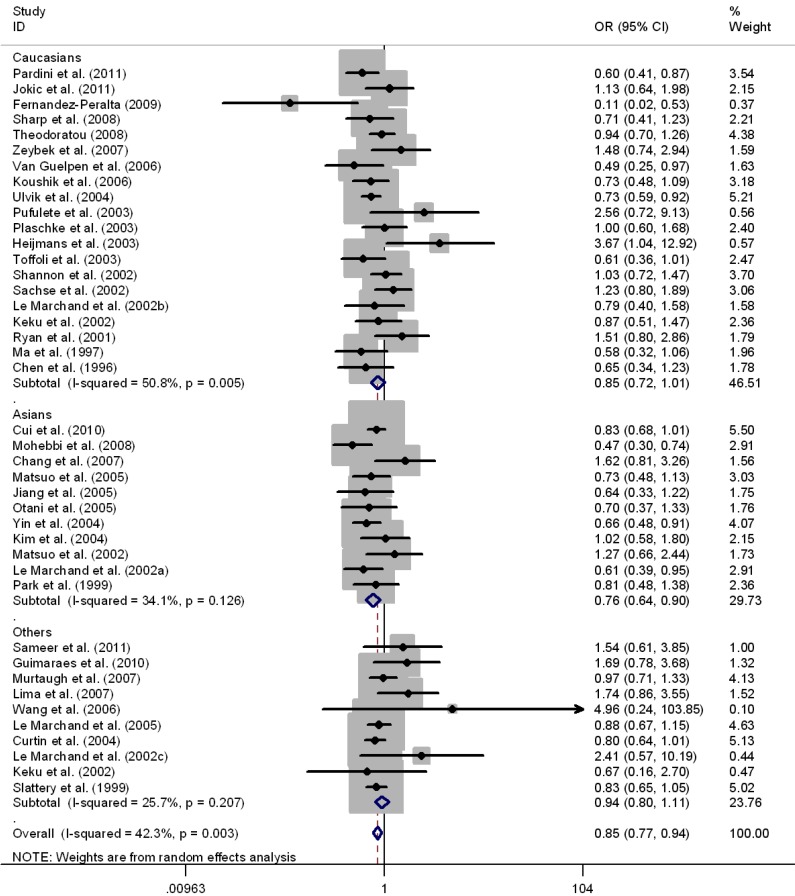

Results of pooled analysis on the associations between MTHFR C677T, MTHFR A1298C, MTRR A66G, MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the risk of CRC were shown in Table 1-3, respectively. There was evidence that the T allele of MTHFR C677T resulted in decreased susceptibility to CRC in a worldwide population (OR = 0.93, 95%CI 0.90-0.96), as well as in Asians (OR = 0.89, 95%CI 0.84-0.94) and Caucasians (OR = 0.92, 95%CI 0.88-0.97). Mild to moderate between-study heterogeneity was found (I2 <50%). Significant associations were also found in the genotypes contrasts in homozygous comparison (TT vs. CC: OR = 0.83, 95%CI 0.77-0.88), in the recessive model (TT vs. TC+CC: OR = 0.84, 95%CI 0.79-0.89), and in the dominant model (TT+TC vs. CC: OR = 0.95, 95%CI 0.91-0.99), except for the comparison of CT vs. CC (OR = 0.98, 95%CI 0.94-1.02) in the worldwide populations (Table 1). The sub-group analysis by ethnicity also revealed significant association in Asians and Caucasians in the above genotype contrasts except for the homozygous contrast in Caucasians. (TT vs. CC, OR = 0.85, 95%CI 0.72-1.01) (Fig.2). Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding 8 studies deviated from HWE 29, 31, 37, 40, 44, 48-50; however, the results were not materially altered in either genetic model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ethnicity-stratified pooled measures on the association between MTHFRC677T polymorphism and colorectal cancer.

| Contrast | Ethnicity | All relevant articles were included (n = 41) | Articles deviated for HWE were excluded (n=33)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value b | OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value b | ||

| T vs. C | Asian | 0.89 | (0.84-0.94)** | FEM | 47.6% | 0.039 | 0.91 | (0.85-0.97)** | FEM | 25.2% | 0.228 |

| Caucasian | 0.92 | (0.88-0.97)** | FEM | 46.4% | 0.012 | 0.93 | (0.88-0.97)** | FEM | 49.1% | 0.012 | |

| others | 0.98 | (0.93-1.04) | FEM | 5.3% | 0.391 | 0.98 | (0.92-1.04) | FEM | 17.1% | 0.295 | |

| All | 0.93 | (0.90-0.96)** | FEM | 43.3% | 0.002 | 0.94 | (0.91-0.97)** | FEM | 38.3% | 0.013 | |

| TT vs. CC | Asian | 0.76 | (0.68-0.86)** | FEM | 34.1% | 0.126 | 0.80 | (0.70-0.92)** | FEM | 29.3% | 0.194 |

| Caucasian | 0.85 | (0.72-1.01) | REM | 50.8% | 0.005 | 0.86 | (0.72-1.03)** | REM | 53.1% | 0.005 | |

| Others | 0.90 | (0.80-1.02) | FEM | 25.9% | 0.214 | 0.90 | (0.78-1.03) | FEM | 35.0% | 0.149 | |

| All | 0.83 | (0.77-0.88)** | FEM | 42.3% | 0.003 | 0.84 | (0.78-0.90)** | FEM | 42.9% | 0.005 | |

| CT vs. CC | Asian | 0.94 | (0.86-1.02) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.711 | 0.95 | (0.86-1.04) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.715 |

| Caucasian | 0.95 | (0.90-1.02) | FEM | 39.9% | 0.034 | 0.95 | (0.89-1.01) | FEM | 46.6% | 0.018 | |

| others | 1.04 | (0.97-1.13) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.984 | 1.03 | (0.95-1.12) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.977 | |

| All | 0.98 | (0.94-1.02) | FEM | 13.0% | 0.241 | 0.97 | (0.93-1.02) | FEM | 17.8% | 0.186 | |

| TT vs. TC+CC | Asian | 0.80 | (0.72-0.89)** | FEM | 19.5% | 0.258 | 0.83 | (0.74-0.94)** | FEM | 13.5% | 0.325 |

| Caucasian | 0.84 | (0.76-0.93)** | REM | 53.7% | 0.002 | 0.89 | (0.74-1.06) | REM | 56.2% | 0.002 | |

| others | 0.88 | (0.78-0.99)* | FEM | 20.9% | 0.257 | 0.88 | (0.78-1.01) | FEM | 30.1% | 0.188 | |

| All | 0.84 | (0.79-0.89)** | FEM | 39.8% | 0.006 | 0.85 | (0.80-0.91)** | FEM | 41.8% | 0.007 | |

| TT+CT vs. CC | Asian | 0.89 | (0.82-0.97)** | FEM | 21.2% | 0.241 | 0.91 | (0.83-1.00)* | FEM | 0.0% | 0.446 |

| Caucasian | 0.93 | (0.88-0.99)* | FEM | 39.1% | 0.039 | 0.93 | (0.87-0.99)* | FEM | 44.7% | 0.024 | |

| others | 1.02 | (0.95-1.09) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.839 | 1.01 | (0.93-1.09) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.767 | |

| All | 0.95 | (0.91-0.99)** | FEM | 27.7% | 0.056 | 0.95 | (0.91-0.99)* | FEM | 26.3% | 0.086 | |

a 8 studies by Sameer, 2011; by Mohebbi,2008; Zeybek, 2007; Koushik, 2006; Le Marchand, 2005; Jiang, 2005; Park, 1999, and Ma, 1997, were excluded as they were deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; b p value for heterogeneity based on Q test; FEM, fixed effect model; REM, random effect model; *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Table 3.

Ethnicity-stratified pooled measures on the association between MTRR A66G /MTR A2756G polymorphism and colorectal cancer.

| Contrast | Ethnicity | MTRR A66G polymorphism and CRC (n=12) | MTR A2756G polymorphism and CRC (n=13) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value a | OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value a | ||

| G vs. A | Asian | 1.12 | (0.95-1.32) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.552 | 1.03 | (0.87-1.21) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.713 |

| Caucasian | 1.09 | (1.01-1.16)* | FEM | 0.0% | 0.434 | 0.96 | (0.85-1.10) | REM | 55.2% | 0.037 | |

| others | 1.25 | (1.03-1.50)* | FEM | 0.0% | 0.697 | 1.19 | (0.95-1.48) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.670 | |

| All | 1.11 | (1.04-1.18)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.661 | 0.98 | (0.92-1.04) | FEM | 36.3% | 0.092 | |

| GG vs. AA | Asian | 1.40 | (0.71-2.77) | REM | 58.3% | 0.091 | 1.30 | (0.81-2.08) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.495 |

| Caucasian | 1.18 | (1.03-1.36)* | FEM | 23.7% | 0.256 | 0.83 | (0.67-1.03) | FEM | 48.1% | 0.073 | |

| Others | 1.63 | (1.08-2.45)* | FEM | 0.0% | 0.693 | 1.49 | (0.81-2.72) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.876 | |

| All | 1.24 | (1.09-1.40)** | FEM | 25.1% | 0.197 | 0.94 | (0.78-1.14) | FEM | 34.4% | 0.107 | |

| GA vs. AA | Asian | 1.03 | (0.82-1.29) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.559 | 0.96 | (0.79-1.18) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.939 |

| Caucasian | 1.15 | (0.93-1.42) | REM | 57.6% | 0.038 | 0.97 | (0.89-1.06) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.426 | |

| Others | 1.14 | (0.86-1.49) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.983 | 1.15 | (0.87-1.52) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.679 | |

| All | 1.09 | (0.99-1.21) | FEM | 17.5% | 0.272 | 0.98 | (0.91-1.06) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.768 | |

| GG vs. GA+AA | Asian | 1.39 | (0.64-3.01) | REM | 69.7% | 0.037 | 1.32 | (0.83-2.10) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.498 |

| Caucasian | 1.10 | (0.99-1.22) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.980 | 0.84 | (0.67-1.04) | FEM | 39.7% | 0.127 | |

| others | 1.56 | (1.08-2.25)* | FEM | 0.0% | 0.651 | 1.44 | (0.79-2.60) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.883 | |

| All | 1.15 | (1.04-1.26)* | FEM | 13.0% | 0.317 | 0.95 | (0.79-1.14) | FEM | 27.3% | 0.169 | |

| GG+GA vs. AA | Asian | 1.09 | (0.88-1.34) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.981 | 0.99 | (0.82-1.21) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.868 |

| Caucasian | 1.17 | (0.96-1.42) | REM | 55.2% | 0.048 | 0.96 | (0.88-1.04) | FEM | 37.4% | 0.143 | |

| others | 1.23 | (0.95-1.59) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.917 | 1.19 | (0.91-1.56) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.680 | |

| All | 1.14 | (1.03-1.25)* | FEM | 7.4% | 0.373 | 0.98 | (0.91-1.05) | FEM | 8.1% | 0.365 | |

a p value for heterogeneity based on Q test; FEM, fixed effect model. REM, random effect model; *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis for MTHFR C677T polymorphism and CRC in Caucasian, Asian, and the worldwide population (TT vs. CC). Each study was shown by a point estimate of the effect size (OR) (size inversely proportional to its variance) and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) (horizontal lines). The whit diamond denotes the pooled OR.

In contrast to the significant association between MTHFR C677T and the risk of CRC, the MTHFR A1298C polymorphism was found to be not significantly related with the risk of CRC. As shown in Table 2, a marginal association was found in the allele comparison (G vs. A: OR = 0.96, 95%CI =0.91-1.00, P = 0.50), and in the homozygous genotypes comparison (GG vs. AA: OR = 0.86, 95%CI = 0.78-0.96), and in the recessive model (GG vs. GA+AA: OR = 0.86, 95%CI = 0.78-0.95). The pooled results were not significantly changed after exclusion of studies deviated from HWE in every contrast (Table 2). However, when we further excluded the studies by Wang et al. and Keku et al., in which the 95%CI did not overlap the lines of the pooling results, the significant associations were all disappeared (G vs. A: OR = 0.97, 95%CI =0.93-1.02; GG vs. AA: OR = 0.92, 95%CI = 0.82-1.03; GG vs. GA+AA: OR = 0.91, 95%CI = 0.81-1.01).

Table 2.

Ethnicity-stratified pooled measures on the association between MTHFR A1298C polymorphism and colorectal cancer.

| Contrast | Ethnicity | All relevant articles were included (n=24) | Articles deviated for HWE were excluded (n=20)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value b | OR | 95%CI | Statistical model | I2(%) | p value b | |||

| C vs. A | Asian | 0.92 | (0.80-1.06) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.680 | 0.90 | (0.77-1.05) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.678 | |

| Caucasian | 0.99 | (0.93-1.05) | FEM | 9.6% | 0.351 | 0.99 | (0.93-1.05) | FEM | 25.9% | 0.206 | ||

| others | 0.93 | (0.86-0.99)* | FEM | 48.8% | 0.068 | 0.91 | (0.85-0.98)* | FEM | 43.1% | 0.118 | ||

| All | 0.96 | (0.91-1.00)* | FEM | 18.6% | 0.207 | 0.95 | (0.91-0.99)* | FEM | 25.4% | 0.146 | ||

| CC vs. AA | Asian | 0.76 | (0.49-1.19) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.488 | 0.75 | (0.44-1.26) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.871 | |

| Caucasian | 0.93 | (0.81-1.07) | FEM | 11.3% | 0.334 | 0.93 | (0.81-1.08) | FEM | 19.9% | 0.260 | ||

| others | 0.79 | (0.67-0.93)** | FEM | 12.1% | 0.337 | 0.78 | (0.66-0.92)** | FEM | 14.4% | 0.322 | ||

| All | 0.86 | (0.78-0.96)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.488 | 0.86 | (0.77-0.96)** | FEM | 8.6% | 0.349 | ||

| CA vs. AA | Asian | 0.95 | (0.80-1.13) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.470 | 0.91 | (0.75-1.09) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.618 | |

| Caucasian | 1.03 | (0.95-1.12) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.610 | 1.03 | (0.94-1.12) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.567 | ||

| others | 0.98 | (0.89-1.08) | FEM | 23.4% | 0.251 | 0.97 | (0.88-1.07) | FEM | 7.6% | 0.368 | ||

| All | 1.00 | (0.94-1.06) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.555 | 0.99 | (0.93-1.06) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.617 | ||

| CC vs. CA+AA | Asian | 0.77 | (0.49-1.19) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.953 | 0.77 | (0.46-1.29) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.878 | |

| Caucasian | 0.91 | (0.80-1.04) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.444 | 0.92 | (0.80-1.06) | FEM | 1.2% | 0.427 | ||

| others | 0.80 | (0.68-0.94)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.670 | 0.79 | (0.67-0.93)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.617 | ||

| All | 0.86 | (0.78-0.95)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.781 | 0.86 | (0.78-0.95)** | FEM | 0.0% | 0.689 | ||

| CC+CA vs. AA | Asian | 0.93 | (0.79-1.10) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.533 | 0.89 | (0.74-1.07) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.622 | |

| Caucasian | 1.01 | (0.93-1.09) | FEM | 0.0% | 0.472 | 1.01 | (0.93-1.10) | FEM | 11.2% | 0.340 | ||

| others | 0.95 | (0.86-1.04) | FEM | 43.4% | 0.101 | 0.93 | (0.85-1.03) | FEM | 35.2% | 0.173 | ||

| All | 0.98 | (0.92-1.03) | FEM | 10.8% | 0.311 | 0.96 | (0.91-1.02) | FEM | 13.2% | 0.290 | ||

a 4 studies by Guimaraes,2011, Fernandez-Peralta, 2010, Sharp, 2008, and Chang, 2007, were excluded as they were deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium;

b p value for heterogeneity based on Q test; FEM, fixed effect model; *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

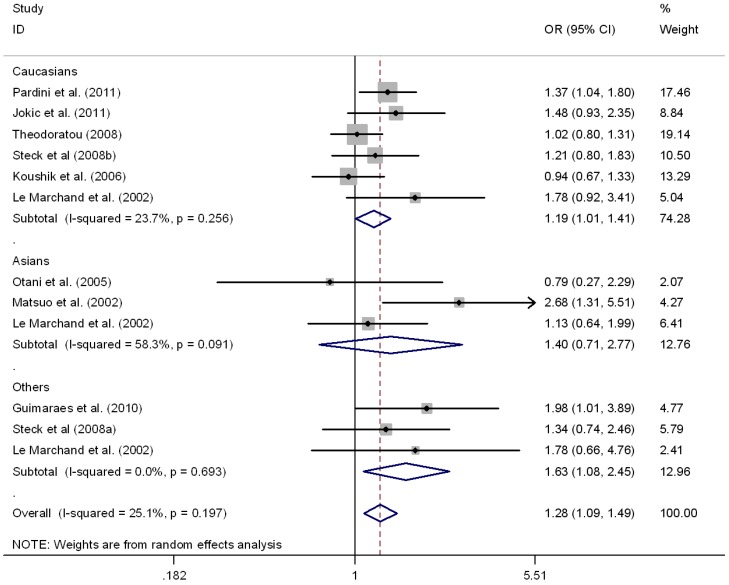

This meta-analysis also provided supporting evidence for the association of MTRR A66G polymorphism and CRC risk. As shown in Table 3, G allele of MTRR A66G resulted in increased susceptibility to CRC in a worldwide population (OR = 1.11, 95%CI 1.01-1.18), as well as in Caucasians (OR = 1.09, 95%CI 1.01-1.16), but not in Asians (OR = 1.12, 95%CI 0.95-1.32). No between-study heterogeneity was found in these comparison (I2 =0.0%). Regarding the genotypes, there was also significant association in homozygous contrast (GG vs. AA) in the worldwide populations (OR = 1.24, 95%CI 1.09-1.40) as well as in the Caucasians (OR = 1.18, 95%CI 1.03-1.36), but not in Asians (OR = 1.40, 95%CI 0.71-2.77) (Fig.3). However, no significant association was found in Asians or Caucasians in other genetic comparisons (Table 3). Furthermore, the pooled results were not significantly altered after excluding one study by Mastuo et al. 47, which was deviated form HWE (data was not shown).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis for MTRR A66G polymorphism and CRC in Caucasian, Asian, and the worldwide population (GG vs. AA). Each study was shown by a point estimate of the effect size (OR) (size inversely proportional to its variance) and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) (horizontal lines). The whit diamond denotes the pooled OR.

No significant association was found for the MTR A2756G polymorphism and the risk of the CRC (Table 3). The polled results were also not significantly altered after exclusion of the study deviated from HWE (data was not shown).

Influence analysis and cumulative analysis

After excluding studies that deviated from HWE in controls, and those in which 95%CI did not overlap the lines of the pooling results, no other studies were found to significantly influence the pooled effects in each genetic model. In the cumulative meta-analysis, no particular time trend was found in the summary estimate (data was not shown).

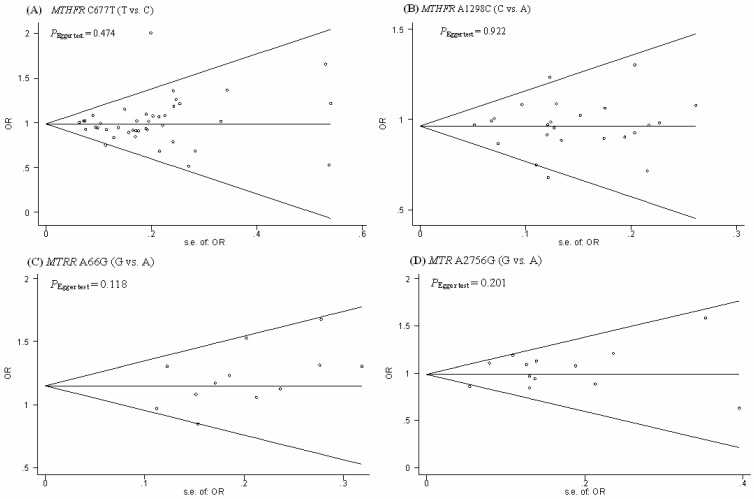

Publication bias

Funnel plots were generated to assess publication bias. The Egger's test was performed to statistically evaluate funnel plot symmetry. The results suggested no publication bias for the association of the MTHFR C677T, MTHFR A1298C, MTRR A66G, MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the risk of CRC (PEgger test = 0.474, 0.922, 0.118, and 0.201, respectively). (Fig.4).

Figure 4.

Begg's funnel plot with the Egger's test for publication bias of MTHFR C677T and A1289C, MTRR A66G, MTR A2756G polymorphism and the risk of CRC. The horizontal line in the funnel plot indicates the fixed-effects summary estimate, whereas the diagonal lines pseudo-95% CI limits about the effect estimate. In the absence of publication bias, studies will be distributed symmetrically above and below the horizontal line.

Discussion

CRC is the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the western world, and it represents the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States 51. The incidence of CRC varies substantially worldwide, with high rates in western countries and low rates in African and Asian countries in general 52. Over the past decades, the roles of folate and genetic polymorphisms of enzymes involved in folate metabolism have attracted considerable interest in epidemiological research on this cancer type. Among these enzymes, MTHFR, MTR, and MTRR, are the three mostly investigated ones in the literature. Unfortunately, conflicting results were obtained ranging from strong links to no association. The divergent results regarding the effects of these genetic polymorphisms upon CRC risk may be attributed to the differences in racial origin of the population, the lifestyle, and the pattern of diet in distinct countries 17. Because of the above-mentioned conflicting results from relatively small studies underpowered to detect the effects, a meta-analysis should be an appropriate approach to obtain a more definitive conclusion.

In the current study, we examined the association of MTHFR C677T and A1298C, MTRR A66G, and MTR A2756G polymorphisms with the susceptibility to CRC, with a total of 41, 24, 12, and 13 studies included, respectively. The data clearly showed that the T allele of C677T polymorphism in MTHFR gene was significantly associated with reduced risk of CRC, while the G allele of A66G polymorphism in MTRR gene might be significantly associated with increased risk of CRC (Table 1 and 3). The sub-group analysis by ethnicity revealed that homozygosity for the T allele (MTHFR 677TT genotype) is associated with significantly reduced risk of CRC in Asians and Caucasians, while the MTR 66GG genotype was found to be significantly increased the risk of CRC in Caucasians but not in Asians. However, no significant association was found between the MTHFR A1298C and MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the risk of CRC (Table 2 and 3). Although a marginal association was found in the allele and genotypes contrasts of MTHFR A1298C (C vs. A, CC vs. AA, and CC vs. CA+AA), the signification was all disappeared after exclusion of one study, in which the 95%CI did not overlap the lines of the pooled results. After excluding studies that deviated from HWE in controls, and those in which 95%CI did not overlap the lines of the pooling results, no other studies were found to significantly influence the pooled effects in each genetic model. Cumulative meta-analysis showed no particular time trend existed in the summary estimate. Furthermore, no potential publication bias was detected by funnel plots and Egger's regression test. These data indicated the robustness of the summary estimate deserved from this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis addressing the associations between the four common polymorphisms of three critical enzymes involved in folate metabolism and the risk of CRC in one study. From 2005 to now, a total of 5 meta-analyses about the association between MTHFR C677T and the risk of CRC have been conducted 52-56. The most recently one conducted by Taioli et al. included 29 studies; 28 of those were included in our meta-analysis, which also included an additional 11 studies primarily published between 2008 and 2012. The pooled results of the current meta-analysis were similar to those by Taioli et al. The pooled OR for genotype TT (vs. CC) was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.77, 0.90), while those were 0.83 (95%CI: 0.74, 0.94) and 0.80 (95%CI: 0.67, 0.96) in Caucasians and Asians, respectively 53. Similarly, the pooled ORs in our study were 0.83(95%CI: 0.77, 0.88), 0.85 (95%CI: 0.72, 1.01), and 0.76 (95%CI: 0.68, 0.86), respectively. The meta-analysis conducted by Huang et al. included 14 studies for the analysis of the association of MTHFR A1298C and the risk of CRC 55. They found that a significantly decreased risk of CRC for 1298C polymorphism in a recessive genetic model in worldwide populations (OR = 0.81, 95%CI 0.70-0.94) and Caucasians (OR = 0.75, 95%CI 0.57-0.99). However, although a marginal association was found in the allele and genotypes contrast of MTHFR A1298C (C vs. A, CC vs. AA, and CC vs. CA+AA), the signification all disappeared after exclusion of the study by Wang et al. and Keku et al. 24, 57, in which the 95%CI did not overlap the lines of the pooled results (G vs. A: OR = 0.97, 95%CI =0.93-1.02; GG vs. AA: OR = 0.92, 95%CI = 0.82-1.03; GG vs. GA+AA: OR = 0.91, 95%CI = 0.81-1.01). The discrepancy between our study and the study by Huang et al. might be explained by the addition of 12 studies and the different methodology of the two studies by Wang et al. and Keku et al. 24, 57. This meta-analysis also provided supporting evidence for the association of MTRR A66G polymorphism and the risk of CRC. G allele of MTRR A66G resulted in increased susceptibility to CRC in a worldwide population (OR = 1.11, 95%CI 1.01-1.18), as well as in Caucasians (OR = 1.09, 95%CI 1.01-1.16), but not in Asians (OR = 1.12, 95%CI 0.95-1.32). In contrast, no significant association was found for the MTR A2756G polymorphism and the risk of CRC.

Reasons for the conflicting results obtained from different studies about the association between the polymorphisms of the three investigated genes involved in folate metabolism and the risk of CRC may be attributed to the genetic heterogeneity in different populations and the clinical heterogeneity in different studies. CRC is well-known as a multifaceted disorder influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. The differences in age, gender, and lifestyle may lead to different results. In the current meta-analysis, most of the studies enrolled subjects of both gender, while some others investigated the association in male patients 37. In addition, several studies have demonstrated the associations between genotypes MTHFR 677CT+TT and MTR 2756AG+GG genotypes with an early disease onset (<50 years of age) 17, 19. Furthermore, folate deficiency which was seen in many studies, might also affect the activity of enzymes involved in DNA synthesis, methylation, and repair pathways, leading to the hypomethylation of DNA and the activation of proto-oncogene, as well as the inducing uracil misincorporation during DNA synthesis, which may also contribute to the discrepancy of different studies 58. In fact, the study by Chen et al. have suggested that dietary methyl supply was particularly critical among patients with MTHFR CC genotypes, which may be at a reduced risk of CRC probably as higher levels of 5,10-MTHF may prevent imbalances of nucleotide pools during DNA synthesis 38. Moreover, the association of alcohol consumption with CRC risk has been related to its anti-folate effects and subsequent effects on DNA methylation 59. Thus, age, gender, and diet particularly folate and alcohol intake, may modify the effects of these gene polymorphisms and the risk of CRC.

Despite the clear strengths of our study such as the larger sample size comparing with the previous individual ones, however, it does have some limitations. First, the present meta-analysis was based primarily on unadjusted effect estimates and CIs (since most studies did not provide the adjusted OR and 95%CI controlling for potential confounding factors), so the effect estimates were relatively imprecise. If individual data were available, adjusted Ors could be obtained to give a more precise analysis. Second, the effects of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions were not addressed in this meta-analysis, and thus the potential roles of the above gene polymorphism may be masked or magnified by other gene-gene/gene-environment interactions. Thirdly, we did not perform stratification analysis by age, gender, drinking status, serum folate levels, etc, which might induce confounding bias. Finally, although the funnel plot and Egger's test showed no publication bias, selection bias may also exist because only published studies were retrieved.

In summary, the current meta-analysis systematically analyzed the association between the risk of CRC and four common polymorphisms of three important genes involved in folate metabolism. The data showed that MTHFR 677T allele might provide protection against CRC in worldwide populations, while MTRR 66G allele might increase the risk of CRC in Caucasians but not in Asians. In contrast, MTHFR A1298C and MTR A2756G polymorphism were unlikely to be related with the risk of CRC. Since potential confounders could not be ruled out completely in this meta-analysis, further studies were needed to confirm these results.

Supplementary Material

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

References

- 1.Stempak JM, Sohn KJ, Chiang EP, Shane B, Kim YI. Cell and stage of transformation-specific effects of folate deficiency on methionine cycle intermediates and DNA methylation in an in vitro model. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(5):981–90. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu XL, Yu J, Zhang HY, Sun MH, Gu J, Du X. et al. Methylation profile of the promoter CpG islands of 31 genes that may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(23):3441–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i23.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slattery ML, Potter JD, Samowitz W, Schaffer D, Leppert M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, diet, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(6):513–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardini B, Kumar R, Naccarati A, Prasad RB, Forsti A, Polakova V. et al. MTHFR and MTRR genotype and haplotype analysis and colorectal cancer susceptibility in a case-control study from the Czech Republic. Mutat Res. 2011;721(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leclerc D, Campeau E, Goyette P, Adjalla CE, Christensen B, Ross M. et al. Human methionine synthase: cDNA cloning and identification of mutations in patients of the cblG complementation group of folate/cobalamin disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(12):1867–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leclerc D, Wilson A, Dumas R, Gafuik C, Song D, Watkins D. et al. Cloning and mapping of a cDNA for methionine synthase reductase, a flavoprotein defective in patients with homocystinuria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(6):3059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frosst P, Blom H, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard C, Matthews R. et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nature genetics. 1995;10(1):111–3. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey LB, Gregory III JF. Polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and other enzymes: metabolic significance, risks and impact on folate requirement. The Journal of nutrition. 1999;129(5):919–22. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Palomeque C, Selhub J, Hunter DJ. Linkage disequilibrium between the 677C> T and 1298A> C polymorphisms in human methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene and their contributions to risk of colorectal cancer. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2002;12(4):339. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisberg IS, Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Chen Z, Curtis Ellison R. et al. The 1298A--> C polymorphism in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR): in vitro expression and association with homocysteine. Atherosclerosis. 2001;156(2):409–15. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo K, Suzuki R, Hamajima N, Ogura M, Kagami Y, Taji H. et al. Association between polymorphisms of folate-and methionine-metabolizing enzymes and susceptibility to malignant lymphoma. Blood. 2001;97(10):3205–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goode EL, Potter JD, Bigler J, Ulrich CM. Methionine synthase D919G polymorphism, folate metabolism, and colorectal adenoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(1):157–62. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaughan DJ, Kluijtmans LAJ, Barbaux S, McMaster D, Young IS, Yarnell JWG. et al. The methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) A66G polymorphism is a novel genetic determinant of plasma homocysteine concentrations. Atherosclerosis. 2001;157(2):451–6. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Peralta AM, Daimiel L, Nejda N, Iglesias D, Medina Arana V, Gonzalez-Aguilera JJ. Association of polymorphisms MTHFR C677T and A1298C with risk of colorectal cancer, genetic and epigenetic characteristic of tumors, and response to chemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(2):141–51. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0779-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan BM, Molloy AM, McManus R, Arfin Q, Kelleher D, Scott JM. et al. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene in colorectal cancer: role in tumor development and significance of allelic loss in tumor progression. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2001;30(3):105–11. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:30:3:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heijmans BT, Boer J, Suchiman HED, Cornelisse CJ, Westendorp RGJ, Kromhout D. et al. A common variant of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene (1p36) is associated with an increased risk of cancer. Cancer research. 2003;63(6):1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guimaraes JL, Ayrizono Mde L, Coy CS, Lima CS. Gene polymorphisms involved in folate and methionine metabolism and increased risk of sporadic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(5):853–61. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theodoratou E, Farrington SM, Tenesa A, McNeill G, Cetnarskyj R, Barnetson RA. et al. Dietary vitamin B6 intake and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(1):171–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima CS, Nascimento H, Bonadia LC, Teori MT, Coy CS, Goes JR. et al. Polymorphisms in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene (MTHFR) and the age of onset of sporadic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(7):757–63. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau J, Antman EM, Jimenez-Silva J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(4):248–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in the meta-analysis estimate. Stata Tech Bull. 1999;47:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25(20):3443–57. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keku T, Millikan R, Worley K, Winkel S, Eaton A, Biscocho L. et al. 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase codon 677 and 1298 polymorphisms and colon cancer in African Americans and whites. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(12):1611–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Marchand L, Donlon T, Hankin JH, Kolonel LN, Wilkens LR, Seifried A. B-vitamin intake, metabolic genes, and colorectal cancer risk (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(3):239–48. doi: 10.1023/a:1015057614870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon B, Gnanasampanthan S, Beilby J, Iacopetta B. A polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene predisposes to colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. Gut. 2002;50(4):520–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jokic M, Brcic-Kostic K, Stefulj J, Catela Ivkovic T, Bozo L, Gamulin M. et al. Association of MTHFR, MTR, MTRR, RFC1, and DHFR gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to sporadic colon cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30(10):771–6. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp L, Little J, Brockton NT, Cotton SC, Masson LF, Haites NE. et al. Polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene, intakes of folate and related B vitamins and colorectal cancer: a case-control study in a population with relatively low folate intake. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(2):379–89. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507801073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeybek U, Yaylim I, Yilmaz H, Agachan B, Ergen A, Arikan S. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer. Cell Biochem Funct. 2007;25(4):419–22. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Guelpen B, Hultdin J, Johansson I, Hallmans G, Stenling R, Riboli E. et al. Low folate levels may protect against colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006;55(10):1461–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koushik A, Kraft P, Fuchs CS, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. et al. Nonsynonymous polymorphisms in genes in the one-carbon metabolism pathway and associations with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(12):2408–17. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulvik A, Vollset SE, Hansen S, Gislefoss R, Jellum E, Ueland PM. Colorectal cancer and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C -> T and methionine synthase 2756A -> G polymorphisms: a study of 2,168 case-control pairs from the JANUS cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toffoli G, Gafà R, Russo A, Lanza G, Dolcetti R, Sartor F. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677 C→ T polymorphism and risk of proximal colon cancer in north Italy. Clinical cancer research. 2003;9(2):743–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pufulete M, Al-Ghnaniem R, Leather AJ, Appleby P, Gout S, Terry C. et al. Folate status, genomic DNA hypomethylation, and risk of colorectal adenoma and cancer: a case control study. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(5):1240–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plaschke J, Schwanebeck U, Pistorius S, Saeger HD, Schackert HK. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms and risk of sporadic and hereditary colorectal cancer with or without microsatellite instability. Cancer Lett. 2003;191(2):179–85. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00633-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sachse C, Smith G, Wilkie MJ, Barrett JH, Waxman R, Sullivan F. et al. A pharmacogenetic study to investigate the role of dietary carcinogens in the etiology of colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(11):1839–49. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Artigas C, Hunter DJ, Fuchs C. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, dietary interactions, and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(6):1098–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Giovannucci E, Kelsey K, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA. et al. A methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56(21):4862–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui LH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Kim HN, Song HR, Piao JM. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer in a Korean population. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohebbi SR, Khatami F, Ghiasi S, Derakhshan F, Atarian H, Zali MR. Reverse association between MTHFR polymorphism (C677T) with sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from bed to bench. 2008;1(2):57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang SC, Lin PC, Lin JK, Yang SH, Wang HS, Li AF. Role of MTHFR polymorphisms and folate levels in different phenotypes of sporadic colorectal cancers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(5):483–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otani T, Iwasaki M, Hanaoka T, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, Natsukawa S. et al. Folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and vitamin B2 intake, genetic polymorphisms of related enzymes, and risk of colorectal cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Japan. Nutr Cancer. 2005;53(1):42–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuo K, Ito H, Wakai K, Hirose K, Saito T, Suzuki T. et al. One-carbon metabolism related gene polymorphisms interact with alcohol drinking to influence the risk of colorectal cancer in Japan. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(12):2164–71. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Q, Chen K, Ma X, Li Q, Yu W, Shu G. et al. Diets, polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and the susceptibility of colon cancer and rectal cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2005;29(2):146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin G, Kono S, Toyomura K, Hagiwara T, Nagano J, Mizoue T. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and A1298C polymorphisms and colorectal cancer: the Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(11):908–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim DH, Ahn YO, Lee BH, Tsuji E, Kiyohara C, Kono S. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism, alcohol intake, and risks of colon and rectal cancers in Korea. Cancer Lett. 2004;216(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuo K, Hamajima N, Hirai T, Kato T, Inoue M, Takezaki T. et al. Methionine synthase reductase gene A66G polymorphism is associated with risk of colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2002;3(4):353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park KS, Mok JW, Kim JC. The 677C > T mutation in 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and colorectal cancer risk. Genet Test. 1999;3(2):233–6. doi: 10.1089/gte.1999.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sameer AS, Shah ZA, Nissar S, Mudassar S, Siddiqi MA. Risk of colorectal cancer associated with the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism in the Kashmiri population. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(2):1200–10. doi: 10.4238/vol10-2gmr1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE. The MTHFR C677T polymorphism and colorectal cancer: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2005;14(5):1198–203. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(9):533–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kono S, Chen K. Genetic polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and colorectal cancer and adenoma. Cancer science. 2005;96(9):535–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taioli E, Garza M, Ahn Y, Bishop D, Bost J, Budai B. et al. Meta-and pooled analyses of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism and colorectal cancer: a HuGE-GSEC review. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;170(10):1207–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hubner RA, Houlston RS. MTHFR C677T and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis of 25 populations. International journal of cancer. 2007;120(5):1027–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Y, Han S, Li Y, Mao Y, Xie Y. Different roles of MTHFR C677T and A1298C polymorphisms in colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Journal of human genetics. 2007;52(1):73–85. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen K, Jiang QT, He HQ. Relationship between metabolic enzyme polymorphism and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(3):331–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J, Gajalakshmi V, Jiang J, Kuriki K, Suzuki S, Nagaya T. et al. Associations between 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase codon 677 and 1298 genetic polymorphisms and environmental factors with reference to susceptibility to colorectal cancer: A case-control study in an Indian population. International journal of cancer. 2006;118(4):991–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zingg JM, Jones PA. Genetic and epigenetic aspects of DNA methylation on genome expression, evolution, mutation and carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18(5):869–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Trichopoulos D, Rosner BA. et al. Folate, methionine, and alcohol intake and risk of colorectal adenoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(11):875–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.11.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.