Introduction

Robert M. Sade, MD

Conflicts of interest come about when one must choose between two or more options that are incompatible. In medicine, they usually relate to choices between serving the interests of patients directly or indirectly versus serving one’s own interests, which might be career-related or financial. A particularly controversial area lies in the relations between physicians and pharmaceutical or device companies. For cardiothoracic surgeons, the most frequent interactions are with device companies.

The high level of public attention to such conflicts of interest has led the drug and device industries and medical specialty societies, including the STS and AATS, to develop guidelines for physician-industry interactions.1 The guidelines generally are not intended to eliminate conflicts of interest, which is impossible, but to “manage” them. To Congress, however, self-imposed management is not enough. Scandalous payments of millions of dollars have received front-page coverage. A recent New York Times article reported, “… the extent of [Dr. David Polly’s] financial entanglements with the company, as detailed by those records, could raise questions about the ability of academic medical centers to manage potential conflicts of interest by faculty members who are also highly paid consultants to medical product companies.”2 Many other newspapers, such as The Wall Street Journal, have printed stories about other egregious transgressions.3

Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa has been the bulldog behind Senate investigations, and introduced a bill that require all health care-related companied to report publicly all payments to physicians: the Physician Payments Sunshine Act. The provisions of this bill were included in the new health care reform law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2009, amending the Social Security Act.4 In the view of Congress, medical centers may not be capable of managing industry payments to physicians, so it seems altogether possible that Congress will eventually enact laws that will entirely sever the financial link between industry and physicians. At the least, we are in a regulatory atmosphere that seems headed toward ever-increasing restrictions on such financial interactions.

In a point-counterpoint discussion that took place at the Society of Thoracic Surgeons 46th Annual Meeting, an argument for institutional oversight of physician-industry financial interactions was made by Stephen Immelt, an attorney who focuses primarily on complex enforcement litigation, representing pharmaceutical companies, medical device companies, academic medical centers and medical schools, and other providers of health care in connection with a wide variety of governmental investigations, both civil and criminal in nature. Taking exception to Immelt’s views, Vincent Gaudiani, a cardiothoracic surgeon who has had long-time interests in quality assurance in cardiac surgery and in relations between physicians and industry, argues that institutional oversight is inadequate and collaboration between physicians, health care institutions, industry, and Congressional leaders is needed to legislate rationality into a chaotic area.

PRO: Conflicts of Interest: The case for institutional oversight of individual consulting activity

Stephen J. Immelt, JD

Twenty years ago, health care fraud and abuse was viewed as the province of shady doctors and crooks engaged in clear and obvious fraud such as billing for non-existent patients. At the same time, there existed a web of financial relationships between physicians and providers and a range of suppliers such as pharmaceutical and device companies. Extravagant entertaining and gifts were common as were a range of other payment relationships. These relationships took place outside the public eye and the participants viewed them as standard business practices, not a form of corruption or a conflict of interest. This was, in essence, a black box.

Here we are in 2010, with meetings generally at an airport hotel, a deli platter for lunch, and increasing insistence that physicians document their consulting activities to the level of a lawyer. Yet still questions linger. What happened?

One explanation is that the health care sector, including the medical profession, lost control over the narrative. Using two key federal statutes – the Anti-kickback Act (AKA) and the False Claims Act – a group of determined prosecutors sought to pry the lid off that black box. What they found was not a pretty picture. To be sure, this did not happen in one step. They started with clinical labs, then moved to dialysis providers, hospitals, academic medicine, then hit the mother lode in pharmaceuticals, an effort that has been expanded in recent years to include devices.5 Some observers have applauded this development.. After all, the AKA is a criminal statute, so these must have been corrupt practices.6

The problem is that the AKA can be construed quite broadly through the so-called “one purpose” test and the huge penalties, which can include exclusion from participation in all governmental health care programs, can make it ruinous to contest the theories. That is not to imply that there were no bad facts in these cases. There were. But the format of these settlements had the effect of casting the issues in extremely broad terms. And the narrative that emerged from these many proceedings was that the health care system suffered from rampant fraud, particularly with respect to the financial relationships.

Another consequence of these various enforcement efforts was to expose the scope and scale of the financial dealings. Putting aside any notion of corruption, there has been increasing discomfort with those appearances. This has been particularly true as more information has emerged about the details of the collaboration between industry and the profession in areas like medical education, publications and treatment standards. But the inflammatory labels applied to these activities do not capture the nuances and good faith efforts to develop and communicate useful scientific information.

Although the “corruption” model continues to play a primary role in driving the mainstream narrative, there has been a recognition that corruption cannot explain all the areas of concern. Increasingly, the discussion has been cast in terms of conflicts of interest. The AMA,7 PhRMA,8 and AdvaMed9 Codes all speak in terms of good ethical practice.

A focus on conflicts of interest has brought an interesting dimension to the discussion. The classic legal paradigm for dealing with conflicts of interest is disclosure and consent.

Acting on that model, we have seen a series of legislative initiatives at the state level focused on disclosure, and the approach of a federal disclosure requirement. And recent settlements in orthopedic and pharma cases have mandated public posting of the company’s financial dealings with physicians and customers.

But does disclosure solve the problem?

The 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) study, Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice, suggests not.10 The IOM study posits that the goal of conflict of interest policies is to protect the integrity of professional judgment, not just to remediate problems after they occur. Defining a conflict of interest broadly as “a set of circumstances that creates a risk that professional judgment on actions regarding a primary interest [e.g. patient care] will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest,” the IOM cautions that failure to adopt a more robust approach to such conflicts may ultimately erode public trust in health care providers. Although the IOM views the identification of conflicts as a crucial undertaking, it considers disclosure to be merely a preliminary step, not a solution. Why is disclosure insufficient? One problem is that patients may not be in a position to analyze the relevance of a disclosed relationship, nor feel comfortable raising it with someone who they are trusting with their care. More importantly, the IOM canvasses the psychological and medical literature and develops an intriguing case for the proposition that unconscious bias plays a much stronger role in decision making than any of us may be prepared to acknowledge. In this regard, such bias poses a larger threat than corruption, and one that disclosure cannot address or mitigate. Thus, as the IOM sees it, there must not only be a system for disclosing conflicts but a way to manage them.

Unfortunately, the IOM report does not identify a clear way forward beyond identifying the need for stronger standards and active management. Yet without effective attention to these issues, the pressure for external regulation will increase, driven by a “corruption” narrative that may seek to reduce further or eliminate financial relationships without regard to any corresponding benefits. One available option that warrants consideration might be to insist that consultant activity be directed through the institutions that employ physicians – namely, academic medical centers and practice organizations – as opposed to being viewed as the independent province of those physicians. Most institutions, and virtually all academic medical centers, already have conflict of interest policies and, more importantly, a mechanism for managing the conflicts. Ensuring that institutions are in a position to manage these relationship would help blunt both the influence and appearance of the payments, and also ensure compliance in other areas such as NIH regulations, Bayh-Dole and policies dealing with the ownership and transfer of intellectual property.

Admittedly, a shift toward institutional funding would work against the interests of private practice physicians, many of whom have been active and productive consultants. But the IOM study challenges the assumption that the public interest in unbiased decision making can be ensured simply by broader disclosure. Even presuming complete good faith, there is only so much an individual physician consultant can do. Certainly, the relationship can be disclosed, but how can that relationship be managed? The burden should be on those entrusted with making professional judgments to demonstrate that the possible bias attendant to a financial relationship can be managed and ameliorated in a meaningful way. Perhaps it may be possible to develop a model for third party oversight of individual consulting arrangements, but until that happens the institutional approach would seem a better option for ensuring that the public supports industry collaboration and avoiding another round of embarrassing enforcement actions.

CON: How Should Physicians Interact with the Healthcare Industry?

Vincent A. Gaudiani, MD

Introduction

Corrupt practices have infiltrated an otherwise enormously fruitful relationship between physicians and big business. These practices have lead two States to pass legislation that substantially changes how business and physicians interact. In this essay we examine whether severing all financial relationships between individual physicians and big business will reduce corruption and improve patient care. This idea is incorrect for reasons we outline, but this relationship does need grooming. We recommend that physician leaders join with legislators and businessmen to craft template legislation to regulate this important relationship. Unless we come together to decide upon optimal pro forma rules, we will continue to get a mishmash of State laws that will serve all parties poorly.

Background

Open heart surgery began with collaboration between big business and visionary surgeons. As many of you know, just after WW II, John Gibbon, a young Philadelphia surgeon, was struggling to develop a cardiopulmonary bypass machine. He enlisted the help of Tom Watson, the founder of IBM, and the result of that collaboration was the beginning of our craft. This beginning was not a fluke. A few years later, Lowell Edwards, a successful aeronautical engineer, challenged Albert Starr to collaborate on a total artificial heart. Dr Starr pointed out that no one had yet built a successful replacement heart valve. The result of that encounter is a company that is still at the forefront of valve replacement technology. Starr and Edwards had barely begun when they encountered Tom Fogarty. Fogarty had already patented the embolectomy catheter that would save thousands of lives and limbs and started the era of less invasive surgery even before the era of large incision surgery had hit its stride. These pioneers and others lit the tinder that would not only save millions of lives, but would create, in less than a lifetime, a huge and vibrant healthcare industry that is the envy of the world.

Now, less than a half century later, industry and physicians have formed increasingly complex relationships to solve increasingly complex clinical problems. For instance, consider the elaborate partnership required to introduce percutaneous aortic valve prostheses into the United States. There are scientific, ethical, regulatory, training, proctoring, and manufacturing issues that can only be solved by committed physicians and businessmen working together. Physicians contribute their time and expertise, and business contributes millions of investors’ dollars and their own special knowledge. Medtronic sponsored a meeting in December 2009, in Minneapolis, MN, to organize studies of CoreValve, a transcatheter aortic valve implantation device. Present at this meeting were surgeons and cardiologists, private practitioners and university professors, the employed and the self employed, and those who worked at one institution and those who practiced at several. The diversity of the physicians was matched by an equally diverse group of business personnel and scientists. All were joined together in the common goal of learning how a new therapy might be tested.

The Problem

Such efforts as these occurring through all the specialties and with both device and pharmaceutical companies could not occur without a ration of the vices that flesh is heir to. These are as common to us as speech itself and deeply a part of our nature: it is the corruption of greed, kickbacks, misrepresentation, and cronyism that have always been the camp followers of legitimate enterprise, be it legal, political, religious, medical, or commercial. Some forms of it are clearly illegal, and all are distasteful. Those who would sever the financial relationship between physicians and industry argue that there have been numerous scandals in which doctors were paid kickbacks to use a certain device or drug. More generally, they argue that physician prescribing behavior is influenced by sales visits and small gifts from industry and that many follow up studies, educational dinners, and speaking fees are sub rosa bribes to encourage use of a particular drug or device. We agree that the business-customer relationship in our field is not the same as that in plumbing supply because we have special ethical responsibilities to the patients, and in fact so do healthcare companies. Therefore we must have a more ethically stringent connection to our suppliers than ordinary businesses

Some Inferences

Given these observations, we can make certain inferences. First, Western democracies have thrived by encouraging private enterprise, and private enterprise requires that businesses create and maintain customers. The customer relationship in every business is complex and interactive, particularly in medicine, because the businessmen and the physicians each have special skills required to create new products and teach their proper use. In addition, most of the contact between industry and physicians has not only been moral, but has produced health, wealth, and employment for millions of people. We should be wary of outlawing whole classes of business relationships unless they are pervasively immoral.

The term “conflict of interest” is omnipresent in discussions such as this, but it is widely misused by all sides. It is the job of all professionals, preachers, lawyers and doctors, to skillfully negotiate these conflicts. What is really at stake here is immoral conduct. We must define it clearly, and punish it appropriately, as I will suggest with a few recommendations at the end of this essay.

Some believe that all business arrangements between physicians and industry should be mediated by an academic institution or hospital. This is deeply ironic because the most damaging behavior between business and medicine occurs at the institutional level, not with individual doctors. You will learn the sad facts when you read the New York Times,11,12 Marcia Angell’s book on big pharma,13 or her article in the New York Review of Books.14 She documents several examples in which big pharma makes major contributions at the medical school level with endowed chairs, at the department level with major grants, and the individual professor level with mid six figure speaking fees. Lo and behold, the professor finds that big pharma’s drug is effective for depression. These and many other recent works document serious malfeasance among physicians, their official institutions, and the business community. They are final proof that all relationships involving money and power require rules and laws to minimize corruption. The key question is what form they should take to minimize our vices without trampling the relationships that have brought us so far.

As a practical matter, how would we as a society enforce a ban on financial relationships between physicians and healthcare businesses? I do not wish to stray too close to the law, but a reasonable man doubts the Constitutionality of such a ban as violation of free speech and equal protection.

Before suggesting some practical solutions, we must recognize one unfortunate attitude that has contributed to the difficulties that exist between business and medicine. Some of our academic medical center colleagues maintain a disdainful view of business, and they look down upon commercial enterprise as beneath the dignity of practice and research. This attitude has been around for many years and remains enormously unwise and ironic. It is unwise because it fails to see that physicians and business are partners in the complex enterprise of caring for the sick. It is ironic because the same institutions that deplore pens with industrial logos have leadership that sits on big pharma boards at six figure incomes and engages in the complex monetary exchanges described above. Both physicians and their institutions must have effective and sometimes financial relationships with business if we are to continue innovating effectively. How should we achieve this?

Some Parameters of a Solution

The crux of the problem is to define a framework for interaction between business and medicine that encourages valuable collaboration, deemphasizes the normal jostle and the imperfections of capitalist interchange, and punishes what is immoral and/or dangerous for patients. So let us begin the discussion of how we should relate with a few observations:

First, business will always be business. No rules will make it otherwise. Most major healthcare companies recognize that in the long run, ethical behavior best serves shareholders’ interest. This does not mean they will shrink from promoting a new and more expensive pain reliever or diuretic if they believe it will be profitable. They may interpret scientific results in their favor and overplay them in marketing efforts. They will be slow to react to negative findings about their products. The First Amendment gives them the right to propose their treatments to the unwary in televised advertisements. Purists will abhor all this, but we live in a capitalist and market driven democracy and, although its motives may disappoint us from time to time, no other system has provided so much for so many. We want our healthcare manufacturers to thrive. They will market their products. Some marketing is just hype, but some of it is genuinely useful education. These businesses should foster their brands and offer their newest products. None of this is corrupt, in my view. Perhaps medical students and physicians need courses to help them to analyze the difference between valuable information and lipstick, both of which are inevitable in a society such as ours.

Second, a business cannot be a business unless it has customers. Peter Drucker, the original management consultant, once said that the purpose of a business is to create customers, and that is a deep truth about the construction of our society.15 We physicians are one group of customers served by business. Patients are another. At every level, our society depends on moral contact between customers and businesses. Therefore, I respectfully propose that we avoid legislation that interferes unduly with this fundamental American relationship. We must aim to regulate these important relationships to achieve better care, not impair them because they might become corrupt.

Third, physicians must act in the best interest of the patients they care for. This is an absolute. Physicians simply cannot choose inferior or unnecessary therapies because they have a strong customer relationship with a business. When two products are comparable and serve the patient, physicians may well choose the product that provides the best customer service or education. That seems a reasonable choice, and such choices will be made regardless of legislation.

Fourth, all major research centers must demand freedom from industrial interference in the research mechanism. This doesn’t require laws, it requires that all such institutions demand academic freedom.

Fifth, we should concentrate on structuring relationships between business and individual physicians that will bear fruit for patients and, for the moment, ignore the many other classes of problems between society and healthcare businesses. For instance, how should the healthcare industry relate to universities that control marketable intellectual property? How should industrial research be governed to prevent bias in outcomes? Industry sponsored research comes out favorable to industry about 80% of the time.16 If a university is receiving substantial income from transferred technology, how does it avoid bias in future dealings with its payer? Should senior medical officials from clinics and universities sit on the boards of major healthcare companies? These and many related questions need work, but should not intrude into consideration of the key relationship between the individual physician and the company.

Finally, any rules we create must account for the variety of ways physicians interact with the business world. We are consultants, teachers, inventors, and investors. Each of these roles must be addressed, and I believe they must be addressed directly between physicians and business. We cannot set rules for physicians through medical institutions because many physicians are not employees, because medical institutions are just another corruptible form of “individual” as noted above, and because we need a separate set of rules for medical institutions and business.

Fortunately, we have an ethical framework to start the process of making safe venue for physicians and business to continue creating products and procedures without endangering patients. Michael Mack and Robert Sade have published that framework for cardiothoracic surgeons blessed by both of our major Societies.1 This is an excellent start, but it is a long way from a robust template of rules that might be incorporated into various State laws. This should be our goal.

In order to achieve this goal, I respectfully suggest that our major Societies convene a meeting with leaders from AdvaMed, distinguished healthcare attorneys, and interested legislators perhaps from Senator Grassley’s office to craft optimal legislation to set the standard for robust, moral interchange between physicians and business. We need help from legislators because they face many similar problems in their relationships with lobbyists that physicians face with business. If such a group can craft a strong template, we can avoid the embarrassing failures itemized by Dr. Angell and others as well as poorly constructed State laws that presume any contact between a doctor and a healthcare business is immoral until proven otherwise. This outcome is even worse than corruption for the many suffering patients who await future therapies that result from the best collaboration between physicians and business.

At about the same time that Dr Gibbon was struggling to develop cardiopulmonary bypass, Peter Drucker had just finished his landmark study, The Concept of the Corporation.17 He wrote, “The central problem of all modern society is not whether we want Big Business but what we want of it, and what organization of Big Business and of the society it serves is best equipped to realize our wishes and demands.” This is the fundamental problem we face as we try to decide how and under what constraints physicians and the healthcare industry should interact. Together we must weed the garden that has produced so much health and wealth.

Concluding Remarks

Robert M. Sade, M.D

This debate focuses on the question of whether the financial connections that link physicians and industry should be broken. The two experts in this debate agree that change is coming in the form of increased scrutiny and regulation, but they have differing views of where regulatory policy is or should be headed.

Should Financial Links Be Broken?

Stephen Immelt is an experienced attorney who represents health care entities in civil and criminal litigation. He provides background to this discussion, showing that an earlier perception that fraud and corruption are rampant in the health care industry has shifted to recognition that some problems could not be explained by corruption but can be explained in terms of conflict of interest. While the legal approach to conflict of interest emphasizes disclosure as a corrective measure, current trends are toward “managing” such conflicts rather than merely disclosing them, but there is no consensus on just how conflicts of interest in physician-industry interactions can best be managed. Immelt suggests that one way to do this is to require that all industry funding of medical research be managed by health care institutions, such as academic medical centers. This idea is receiving serious consideration at the national level, he says, and he sees it as a viable way to avoid the loss of public trust engendered by the highly publicized scandals of recent years.

Vincent Gaudiani disagrees with the effectiveness of this approach. Instead, he speaks of the historic productiveness of physician-industry collaboration and the importance of maintaining collaborative bonds. Human vices, he says, are omnipresent throughout human commerce and can be expected in this area as well. Starting with these observations, he draws some inferences that should guide problem-solving in physician-industry relations: solutions should encourage collaboration while recognizing but deemphasizing the disorder and untidiness inherent in capitalism. Immoral activities should be made illegal and appropriately punished. He describes several measures that could constitute a framework for effective policies, then proposes a consensus meeting, bringing together physicians, health care organizations, attorneys, industry leaders, and legislators to craft legislation that would put meat on the skeletal framework he has described.

Additional Considerations

Relations between industry and physicians have a checkered history. As recently as the 1950s and 1960s, contacts between industry representatives and physicians were seen in a strongly positive light; drug reps were viewed as important sources of information for physicians. That light has dimmed considerably in recent decades, to near extinction. Since the turn of this century, frank condemnation of such contacts has become prominent in both the medical literature and lay press.

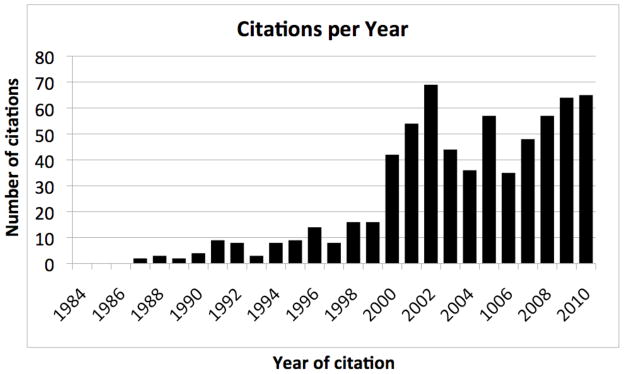

The number of articles in the medical literature dealing with conflicts of interest in health care professionals’ relations with industry has grown over the past 15 years.18 (Figure 1) No paper on this topic was published until one appeared in 1987. Thereafter, the number of articles per year grew slowly, remaining in the range of 10–15 through the 1990s. In 2000, the number jumped to the range of 35 to 70 papers per year, stimulated at least in part by several high-profile scandals in medical research. This plateau has been sustained through 2010.

Figure 1.

Health Care Professionals’ Conflicts of Interest Related to Industry: Number of Citations Per Year in PubMed. The numbers were derived from a PubMed search using the search term “conflict of interest industry,” with limitations to English language and core clinical journals. (Adapted from Reference 18)

Most published articles during this period have been critical of interactions between industry and health care professionals, and many propose regulation, some draconian, of physician-industry interactions. Yet, there is a small but eloquent and persuasive literature arguing that the seriousness of these problems has been overblown.

In a widely cited paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, Thomas Stossel asserts that none of the justifications for regulating physician-industry interactions hold up under close inspection.19 In countering several types of arguments for regulation, for example, he points out that no data exist showing that research misbehavior is more common in studies that are sponsored by industry than in those that are not. There is also no evidence that financial interactions are disproportionately associated with fabrication of data, nor is there any credible evidence that industry consultants are biased positively toward the companies for which they consult. No data supports claims of a low quality of research done under commercial sponsorship. Moreover, there is no evidence that public trust in the health care enterprise has suffered because of high-profile scandals involving physician-industrial interactions. To the contrary, Stossel says, a great deal of damage can be done by excessive regulation arising from overreaction to adverse events, by erecting barriers between academic and industrial entities with a history of highly productive collaboration in the past.

Evidence or lack of it, however, does not drive public policy, rather, the impetus for change comes mostly from anecdote, publicity, and the perceptions they generate. It seems likely that policy making that is designed to rectify perceptions of wrongdoing in relations between physicians and industry will not be deflected by rational arguments, such as Stossel’s, which point to greater harm than benefit of such policies. It seems nearly certain that further regulation is in the future of industry-sponsored biomedical research. Regulation of physician-industry interactions seems highly likely to develop over the next few years through a political process of compromise and accommodation within our health care institutions, accrediting agencies, and lawmakers. What is uncertain is the form and substance of future regulations. All sides in the many debates surrounding these issues hope to influence the political process, guaranteeing that we will be hearing much more about this issue in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sade's role in this publication was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, Medical University of South Carolina’s Clinical and Translational Science Award Number UL1RR029882. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the Society of Thoracic Surgeons 46th Annual Meeting, January 25–27, 2010, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

References

- 1.Mack MJ, Sade RM for the American Association for Thoracic Surgery Ethics Committee and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Standards and Ethics Committee. Relations Between Cardiothoracic Surgeons and Industry. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 May;87(5):1334–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 May;137(5):1047–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier B. 2nd Medtronic consultant draws Senate’s scrutiny. [Accessed December 2, 2010];New York Times. 2009 Jul 28;:B2. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/29/business/29device.html.

- 3.Hensley S. Harvard psychiatrists under fire for drug-company funding. [Accessed December 2, 2010.];Wall Street Journal. 2008 Jun 9; Available at http://blogs.wsj.com/health/2008/06/09/harvard-psychiatrists-under-fire-for-drug-company-funding/

- 4.42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7h (2010)

- 5.Kalb PE. Health care fraud and abuse. JAMA. 1999;282(12):1163–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby RT. The Criminalization of Medicine: America's War on Doctors. Praeger; Santa Barbara, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics: Current Opinions with Annotations, 2010–2011. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008. Opinion 8.061 and addendum: gifts to physicians from industry; pp. 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pharmaceutical Research Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) [Accessed December 2, 2010];Code on interactions with healthcare professionals. Available at http://www.phrma.org/files/attachments/PhRMA%20Marketing%20Code%202008.pdf.

- 9.Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) [Accessed December 2, 2010];Code of ethics on interactions with health care professionals. Available at http://www.advamed.org/NR/rdonlyres/61D30455-F7E9-4081-B219-12D6CE347585/0/AdvaMedCodeofEthicsRevisedandRestatedEffective20090701.pdf. [PubMed]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2009. [Accessed December 2, 2010]. Available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/Conflict-of-Interest-in-Medical-Research-Education-and-Practice.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris G, Carey B. Researchers fail to reveal full drug pay. [Accessed December 14, 2010];New York Times. 2008 Jun 8; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/08/us/08conflict.html?ex=1370664000&en=a8295c43acc64e60&ei=5124&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink.

- 12.Harris G, Carey B. A doctor’s underreported transactions. [Accessed December 14, 2010];New York Times. 2008 Jun 8; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2008/06/08/us/20080608_CONFLICT_GRAPHIC.html.

- 13.Angell M. The New York Review of Books. Jul 15, 2004. The Truth About the Drug Companies. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angell M. Drug Companies & Doctors: A Story of Corruption. The New York Review of Books. 2009 Jan 15;56(1) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drucker P. The Practice of Management. New York: HarperBusiness; 1954. reissue edition 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(4):454–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drucker P. Concept of the Corporation. New York: John Day; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sade RM. Dangerous Liaisons? Industry Relations with Health Professionals. J Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2009;37(3):398–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stossel TP. Regulating academic-industrial research relationships—solving problems or stifling progress? N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 8;353(10):1060–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb051758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]