Abstract

Purpose

To compare the characteristics of HER receptors and their ligands deregulation between primary tumor and corresponding brain metastases of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).

Experimental design

Fifty five NSCLC primary tumors (PT) and corresponding brain metastases (BM) specimens were examined for the immunohistochemical expression of EGFR, phosphorylated (p)–EGFR, Her2, Her3, and p-Her3, and their ligands EGF, TGF-α, amphiregulin, epiregulin, betacellulin, heparin-binding EGFR-like growth factor, and neuregulins-1 and -2. Analysis of EGFR copy number using fluorescent in situ hybridization and mutation by PCR-based sequencing was also performed.

Results

Metastases showed significantly higher immunohistochemical expression of EGF (membrane, BM 66.0 vs. PT 48.5; P=0.027; and nucleus, BM 92.2 vs. 67.4; P=0.008), amphiregulin (nucleus, BM 53.7 vs. PT 33.7; P=0.019), p-EGFR (membrane, BM 161.5 vs. PT 76.0; P<0.0001; and cytoplasm, BM 101.5 vs. PT 55.9; P=0.014), and p-Her3 (membrane, BM 25.0 vs. PT 3.7; P=0.001) than primary tumors (PT) did. Primary tumors showed significantly higher expression of cytoplasmic TGF–α (PT 149.8 vs. BM 111.3; P=0.008) and neuregulin-1 (PT 158.5 vs. BM 122.8; P=0.006). In adenocarcinomas, a similar high frequency of EGFR copy number gain (high polysomy and amplification) was detected in primary (65%) and brain metastasis (63%) sites. However, adenocarcinoma metastases (30%) showed higher frequency of EGFR amplification than corresponding primary tumors (10%). Patients whose primary tumors showed EGFR amplification tended to develop brain metastases at an earlier time points.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that NSCLC brain metastases have some significant differences in HER family receptors-related abnormalities from primary lung tumors.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States (1). Lung cancer includes several histological types, the most frequently occurring of which (~80%) are two types of non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (1). The brain is one of the main sites of metastasis in patients with lung cancer: brain metastasis has an incidence of up to 60% in patients with lung adenocarcinoma (2–5). The median survival for lung cancer patients with brain metastasis is usually 3–6 months (5, 6). The use of systemic chemotherapy and cranial irradiation has been shown to be unsuccessful in the treatment of NSCLC brain metastasis (2, 7), and this in turn has motivated the search for new therapeutic strategies for this disease.

During the past few years, significant advances have been made in the development of new molecularly targeted agents for lung cancer (8). One example of such targets is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that belongs to the HER family tyrosine kinase (TK) receptors composed of four homologous cell membrane receptors, including Her2 and Her3 (9). These three receptors are activated by nine known ligands, including, EGF, transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α), amphiregulin, epiregulin, betacellulin (BTC), heparin-binding EGFR-like growth factor (HB-EGF), and neuregulins-1 (NRG1), and -2 (NRG2) (10–12). Deregulation of HER receptors, especially EGFR, appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of NSCLC (13). In lung cancer cells, the constitutive activation of EGFR is achieved by several mechanisms, including increased production of ligands, increased levels of the receptor, and mutation of EGFR (13–15).

Small-molecule inhibitors that target the TK domain of the EGFR produce tumor responses in approximately 10% of patients with advanced NSCLC that has progressed despite prior chemotherapy (13, 16). However, the brain is still a frequent site of disease recurrence in NSCLC patients after an initial response to treatment with EGFR TK inhibitors (TKIs), regardless of disease control in the lungs (3). Activating mutations in the EGFR TK domain, an increased EGFR copy number, and increased EGFR protein expression have been associated with a favorable response to treatment with EGFR TKIs (13, 16). Previous reports demonstrated that metastatic NSCLC brain tumors respond to EGFR TKIs (17, 18). However, it is still unclear whether EGFR and its related receptors’ abnormalities differ in metastases compared with primary NSCLC tumors.

The identification of differences in the deregulation of HER ligands and receptors in NSCLC primary tumors and corresponding metastases may explain differences in the response to HER receptors targeted therapy in this tumor type, and these differences need to be considered in the analysis of predictive biomarker used in clinical trials. In the present study, we investigated the immunohistochemical expression of three HER receptors (EGFR, Her2 and Her3) implicated in the pathogenesis of NSCLC cancer, and eight out of their nine known ligands (EGF, TGF-α, amphiregulin, epiregulin, BTC, HB-EGF, NRG1, and NRG2, in 55 paired primary and brain metastasis NSCLCs. In addition, we compared EGFR copy number and mutation abnormalities using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and PCR-based sequencing analyses, respectively.

Material and Methods

NSCLC tissue specimens

We obtained archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material from surgically resected specimens from 55 NSCLC patients with primary lung cancers and corresponding brain metastases containing tumor tissues and collected between 1988 and 2002. These cases were selected based on the availability of enough archival tissue for the immunohistochemistry and FISH analyses. All specimens were from the Lung Cancer tissue bank at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) which is approved by the M. D. Anderson institutional review board. After histologic examination, TMAs were constructed using three 1-mm-diameter cores per tumor.

Detailed clinical and pathological information—including demographic, pathologic TNM staging, overall survival, and time of brain metastasis occurrence—was obtained for all patients (Table 1). Pathologic TNM stage had been determined for lung cancers according to the revised International System for Staging Lung Cancer (19) at time of primary tumor surgery with curative intent. In all cases the NSCLC brain metastases were solitary, and 11 patients also developed metastases at other brain sites (median, 13 months; range, <1–94 months) over a median period of 12 months (range, <1–27 months). Forty-four (80%) of 55 patients developed clinically detectable brain metastases after primary lung cancer surgical resection (metachronous tumors; median, 13 months; range, <1–94 months); in 11 (20%) patients the brain metastases were detected at the same time as the lung tumors (synchronous tumors), and they were surgically removed before (median, less <1 month; range, <1–11 months) the primary lung cancer surgery.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic features of 55 NSCLC patients with primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases.

| Characteristic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Histology | ||

| Ademocarcinoma | 40 | 73 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 13 | 23 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 1 | 2 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 | 2 |

| Age | ||

| ≤60 years | 30 | 55 |

| >60 years | 25 | 45 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 19 | 35 |

| Male | 36 | 65 |

| Pathological Stage1 | ||

| I | 13 | 24 |

| II | 10 | 18 |

| III | 18 | 33 |

| IV2 | 14 | 25 |

The staging was performed at time of surgical resection of the primary lung tumor.

In 11 cases the brain metastases were surgically removed before the primary tumor.

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation

For our analysis, antibodies against the following molecules were purchased and used: EGF (EMD Biosciences; San Diego, CA; dilution 1:50), amphiregulin (Lab Vision, Freemont, CA; dilution 1:150), TGF-α (EMD Biosciences; dilution 1:150), epiregulin (EPG, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; dilution 1:10), betacellulin (BTC, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; dilution 1:10), heparin-binding EGFR-like growth factor (HB-EGF, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; dilution 1:10), neuregulin 1 (NRG1, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; dilution 1:10), neuregulin 2 (NRG2, Abcam Inc, Cambridge, MA; dilution 1:50), EGFR (Zymed, Carlsbad, CA; clone 31G7; dilution 1:100), phosphorylated (p)–EGFR Tyr 1086 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, dilution 1:100), Her2 (Dako, San Diego, CA; dilution 1:100), Her3 (GenTex; San Antonio, TX; dilution 1:50), and p-Her3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; dilution 1:100). Immunohistochemical staining was performed using 5-µg-thick TMA histologic sections as previously described (20). The immunohistochemical protein expression was quantified, using white light microscopy with ×20 magnification, by two experienced thoracic pathologists (M.S. and I.W.) blinded to clinical and other molecular variables. All markers were examined for membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus localization in tumor cells. As previously described (21–23), immunohistochemical expression was quantified using a three-value intensity score (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) for all markers, except for membrane EGFR and p-EGFR, for which a four-value intensity score (0, 1+, 2+, 3+, and 4+), and the percentage (0% to 100%) of the extent of reactivity were used. Next, expression scores were obtained by multiplying the intensity and reactivity extension values (range, 0–300 for all markers, except for membrane EGFR and p-EGFR with a range of 0–400). For each case of primary tumor and metastasis, the immunohistochemical expression of the markers was averaged using the cores available per tumor site.

EGFR FISH analysis

We analyzed the gene copy number per cell using the LSI EGFR SpectrumOrange/CEP 7 SpectrumGreen Probe (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL), as previously described (24, 25). Tumor specimens were classified into six FISH strata according to the frequency of cells with each EGFR gene copy number and referred to the chromosome 7 centromere, as follows: (1) disomy (three or four copies in <10% of cells); (2) low trisomy (three copies in 10% to <40% of cells and four copies in <10% of cells); (3) high trisomy (three copies in ≥40% of cells and four copies in <10% of cells); (4) low polysomy (four copies in 10% to <40% of cells); (5) high polysomy (four or more copies in ≥40% of cells); and (6) gene amplification (presence of loose or tight EGFR gene clusters with ≥4 copies, EGFR gene to CEP 7 ratio ≥ 2, or 15 copies of EGFR per cell in ≥10% of cells). The high polysomy and gene amplification categories were considered to indicate high EGFR copy number (EGFR FISH positive), and the other categories were considered to indicate no significant increase in the EGFR copy number (EGFR FISH negative), as previously described (24, 25). For each case of primary tumor and metastasis, the FISH EGFR copy number was quantified by counting cells representing each core available per tumor site.

EGFR mutation analysis

Exons 18–21 of EGFR were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified using intron-based primers as previously described (26). Approximately 200 microdissected FFPE cells were used for each PCR amplification. All PCR products were directly sequenced using the Applied Biosystems PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing method. All sequence variants were confirmed by independent PCR amplifications from at least two independent microdissections and DNA extraction, and the variants were sequenced in both directions, as previously reported (26).

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized using standard descriptive statistics and frequency tabulations. Associations between the marker expression and patients’ clinical demographical variables, including age, sex, histology type, and pathologic stage, were assessed using appropriate methods, including the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test the differences in biomarker expression between primary lung tumors and brain metastases. Cox proportional hazard models were used for univariate analysis of time to metastasis according to biomarker expression. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals and P values are reported. All tests were two-sided. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Immunohistochemical expression of HER receptors and ligands in NSCLC primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases

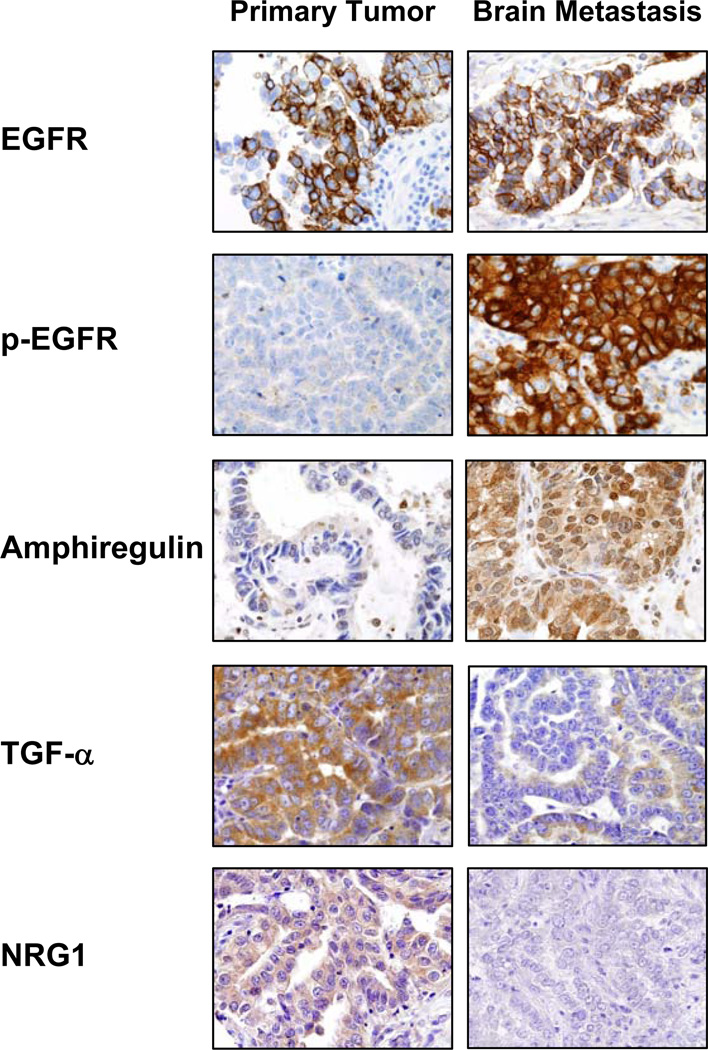

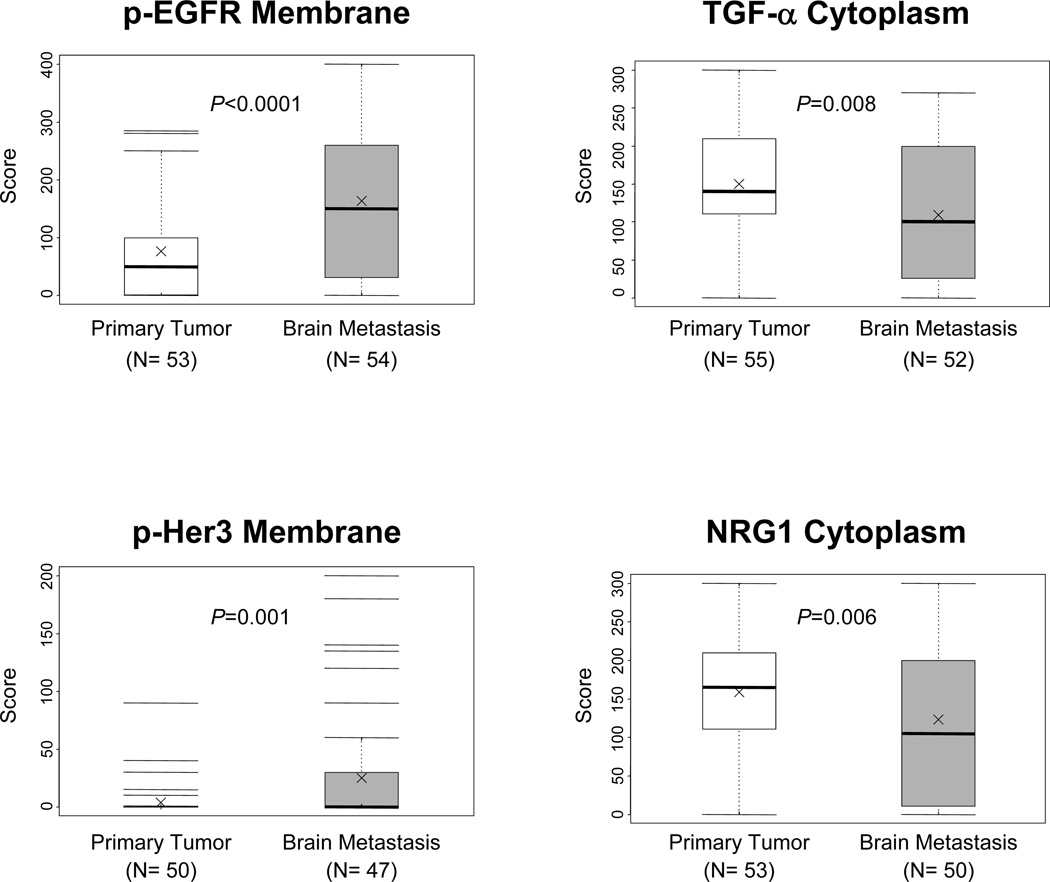

Most markers, including the ligands EGF, amphiregulin, TGF-α, epiregulin, BTC, NRG1, and NRG2, and the receptors EGFR, p-EGFR, Her2, Her3, and p-Her3 showed protein expression in tumor cells from primary and metastasis sites at the membrane and cytoplasm levels (Figure 1, and Supplementary Table 1). Of those, EGF, amphiregulin, epiregulin, NRG1, NRG2, p-EGFR, and p-Her3 showed also nuclear expression in malignant cells (Figure 1, and Supplementary Figure 1). The ligand HB-EGFR expressed only in the cytoplasm of cancer cells. Although showing overlapping, brain metastases had significantly higher immunohistochemical expression scores of EGF (membrane, metastasis 66.0 versus primary 48.5, P=0.027; and nucleus, metastasis 92.2 versus primary 67.4, P=0.008), amphiregulin (nucleus, metastasis 55.4 versus primary 33.7, P=0.019), p-EGFR (membrane, metastasis 161.5 versus primary 76.0, P<0.0001; and cytoplasm metastasis 101.5 versus primary 55.9, P=0.014), and p-Her3 (membrane, metastasis 25.0 versus primary 3.7, P=0.001) than did corresponding primary tumors (Figure 2, and Supplementary Table 1). Only the protein expression score of TGF-α (primary 149.8 versus metastasis 111.3; P=0.008) and NRG1 (primary 158.5 versus metastasis 122.8; P=0.006) at the cytoplasmic level was significantly higher in malignant cells from primary tumors than in brain metastasis cells (Figure 2, and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Representative microphotographs of immunohistochemical expression of EGFR and p-EGFR, and the ligands amphiregulin, TFG-α, and NRG1 in primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases (magnification, ×400). All markers showed protein expression (brown staining) in tumor cells from primary and/or metastasis sites at the membrane and cytoplasm levels. Amphiregulin showed also nuclear expression in malignant cells.

Figure 2.

Box plots showing scores of immunohistochemical expression of p-EGFR, TGF-α, p-Her3 and NRG1 markers comparing primary tumors with corresponding brain metastases. P values comparing primary tumors and and brain metastasis are shown for all comparisons. Bars indicate median, and x mean score.

EGFR copy number analysis by FISH in NSCLC primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases

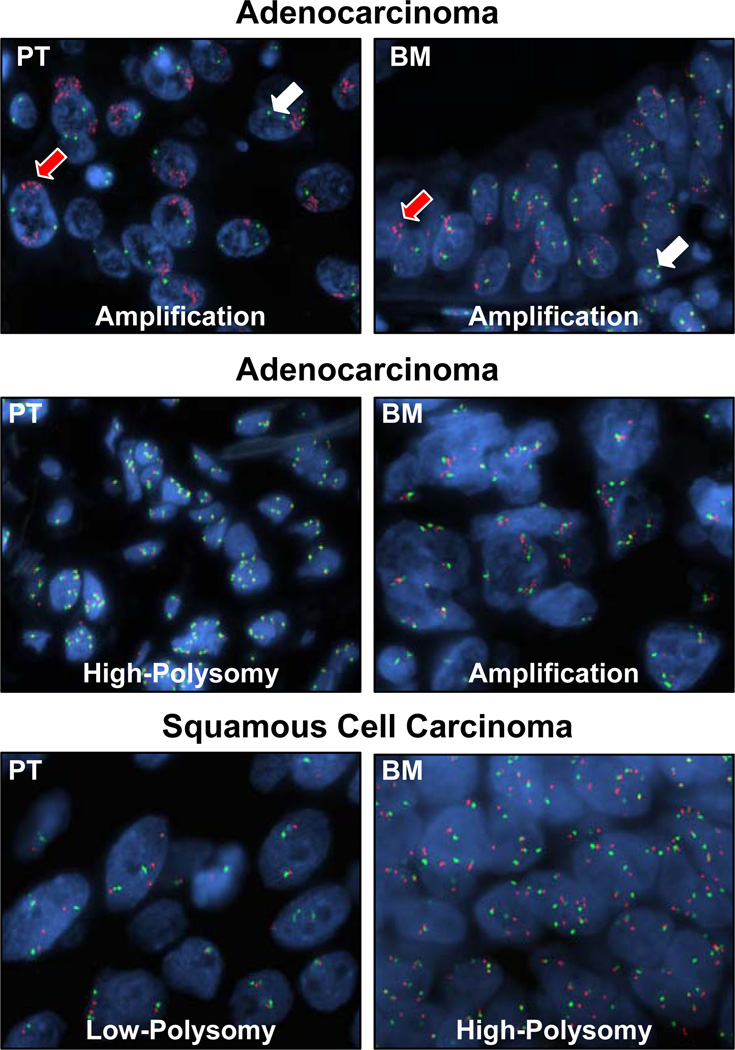

Overall, the presence of high frequency of gain in EGFR copy number (FISH positive: high polysomy and amplification; Figure 3) was similar in NSCLC primary (34/55 [62%]) and brain metastasis (35/55 [64%]) sites (Table 2). Although a relatively lower frequency of high polysomy was detected in metastases than in primary tumors (33% versus 47%), brain metastases showed a nonsignificant higher frequency of EGFR amplification than corresponding primary tumors did (31 versus 15%, P = 0.53). In adenocarcinomas (n=40 cases), a similar frequency of gain in EGFR copy number was detected in primary tumors (65%) and corresponding metastases (63%). However, brain metastases of lung adenocarcinoma showed a nonsignificant higher frequency of EGFR amplification than primary lung tumors (30% versus 10%, P = 0.53). Although a higher frequency in EGFR copy number gain was detected in brain metastases (62%) than primary tumors (46%) among squamous cell carcinomas (Table 2), the data were difficult to interpret because of the small number of cases available for analysis. The concordance of EGFR copy number abnormalities between both tumor sites was higher for the cases with primary and metastasis tumors clinically detected as synchronous lesions (11/11, 100%) than those diagnosed as metachronous tumors (34/44, 77%).

Figure 3.

Representative microphotographs of FISH showing EGFR copy number in primary tumors (PT) and corresponding brain metastases (BM) (magnification, ×1000). Red signals (red arrows) represent EGFR gene copies and green signals (white arrows) represent the chromosome 7 centromere probe. Cell nuclei stained blue with DAPI. High polysomy is defined by ≥4 copies in ≥40% of cells, and gene amplification by the presence of loose or tight EGFR gene clusters and a ratio of EGFR gene to chromosome of 2 or 15 copies of EGFR per cell in 10% of the analyzed cells.

Table 2.

EGFR copy number by FISH in 55 NSCLC primary and corresponding brain metastases by tumor histology.

| Copy Number Categories |

Adenocarcinoma (n=40) |

Squamous Cell Ca (n=13) |

Total (n=55)1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Metastasis | Primary | Metastasis | Primary | Metastasis | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| FISH Negative | 14 (35) | 15 (37) | 7 (54) | 5 (38) | 21 (40) | 20 (36) |

| Disomy | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Trisomy | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Low Polysomy | 11 (28) | 11 (27) | 6 (46) | 5 (39) | 17 (31) | 16 (29) |

| FISH Positive | 26 (65) | 25 (63) | 6 (46) | 8 (62) | 34 (62) | 35 (64) |

| High Polysomy | 22 (55) | 13 (33) | 2 (15) | 5 (39) | 26 (47) | 18 (33) |

| Amplification | 4 (10) | 12 (30) | 4 (31) | 3 (23) | 8 (15) | 17 (31) |

One adenosquamous carcinoma and one large cell carcinoma showed EGFR high polysomy in the primary tumors and amplification in the brain metastasis specimen.

A relatively high level of concordance (46/55 [84%]) for gain in EGFR copy number gain was found between primary tumors and metastases (Supplementary Table 2). Sixteen (29%) paired primary/metastasis cases were EGFR FISH negative in both sites, whereas 30 (55%) paired cases showed gain in EGFR copy number at both tumor sites. Discordance in EGFR copy number status was detected in 9 cases (16%); in 6 of these, brain metastasis sites had a gain in copy number while primary tumors were FISH negative. The levels of concordance for high polysomy (15/30 [50%]) and amplification (6/18 [33%]) were low when primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases were compared. To assess heterogeneity in EGFR copy number abnormalities in the different cores examined per tumor sample, we examined in paired primary tumors and metastases from 14 cases the level of concordance between the level of the most advanced gene copy number abnormality detected in all cores examined per tumor site. In primary tumors, the concordance was 100% (22 comparisons), and in the brain metastases was 90% (27/30 comparisons).

Two consecutive brain metastasis samples were available for analysis from each of five adenocarcinoma cases. The length of time between the consecutive brain metastasis were 1, 6, 10, 16 (2 cases), and 31 months. In all comparisons, paired consecutive brain metastasis specimens showed identical EGFR copy number status. One pair was FISH negative and the other four were FISH positive. FISH-positive specimens included two pairs showing EGFR high polysomy and two showing gene amplification.

We correlated EGFR copy number status with markers’ immunohistochemical expression at both tumor sites. The only associations detected were that EGFR FISH-positive primary tumors and brain metastases demonstrated significantly higher protein expression scores of nuclear p-EGFR (P=0.018) and cytoplasmic Her2 (P=0.015) than FISH negative tumors. In contrast, FISH positive tumors demonstrated lower expression of BTC (P=0.0293) than FISH negative tumors.

EGFR mutations in NSCLC primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases

We successfully amplified and sequenced DNA obtained from primary tumors and metastases samples from 42 cases, including 30 adenocarcinomas, for exons 19 and 21 of EGFR, which harbor higher than 90% of tyrosine kinase activating mutations of the gene (27). We detected only one case with EGFR mutation (exon 19, point mutation TTA2239-2240CCA, Leu747Pro) which was present in both sites, primary and metastasis, in a adenocarcinoma obtained from a patient female and never smoker.

Correlation between immunohistochemical expression of markers and EGFR copy number and time to brain metastasis

We investigated the correlation between the immunohistochemical expression of the markers examined and EGFR copy number abnormalities in primary lung tumors and the time to brain metastasis development. In this analysis, we included only the 44 patients whose brain metastases were diagnosed after surgical resection of the primary tumor. Overall, the median time to brain metastasis for all 44 patients was 1.23 years (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 0.89–1.62 years). The median time to brain metastasis development for patients with adenocarcinoma was 1.43 years (95% CI, 0.96–2.04 years), and that for patients with squamous cell carcinoma was 0.89 years (95% CI, 0.63 to not available). Using the Cox proportional hazard regression models, we identified that adenocarcinoma, compared with squamous cell carcinoma, was significantly correlated with a longer time to brain metastasis occurrence (P=0.009; HR, 0.347; 95% CI, 0.157–0.769), whereas EGFR membrane protein expression scores (P=0.025; HR, 1.003; 95% CI, 1.000–1.006) and EGFR amplification (vs. no-amplification) were significantly correlated (P=0.0039; HR, 3.492; 95% CI, 1.494–8.162) with a shorter time to brain metastasis development. None of these markers were demonstrated in the multivariate analysis to be statistically significant predictors of metastasis development. However, in the multivariate analysis, when we analyzed time to brain metastasis development in the subset of 39 patients who developed a single brain metastasis (excluding the five patients who developed two consecutive metastases in the brain) after primary tumor diagnosis, we found that adenocarcinoma, compared with squamous cell carcinoma, was significantly correlated with a longer time to brain metastasis occurrence (P=0.031; HR, 0.373; 95% CI, 0.152–0.917). In contrast, EGFR amplification (vs. no-amplification) was significantly correlated (P=0.0033; HR, 4.452; 95% CI, 1.645–12.053) with a shorter time to brain metastasis development.

Discussion

In NSCLC, overexpression and activation of EGFR, Her2, and Her3 are well known phenomena (9, 13). However, to the best of our knowledge, the overexpression of those TK receptors has not been previously reported in NSCLC brain metastasis. In this study, we have described for the first time higher levels of immunohistochemical expression of EGFR, p-EGFR, Her2, Her3, and p-Her3 in a series of NSCLC brain metastases using TMA specimens. Interestingly, we found that the expression of phosphorylated forms of EGFR and Her3 proteins at the cytoplasmic and membrane level of malignant cells was significantly increased in brain metastasis compared with expression in corresponding primary lung tumors. Although these data need to be validated in a larger set of specimens, these findings are consistent with the notion that activation of the EGFR and Her3 pathways is important in the progression and metastasis of lung cancer (13, 16). Similarly to brain metastasis, we recently showed that in EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinomas, p-EGFR immunohistochemical expression was significantly increased in nine lymph node metastases compared with expression in corresponding primary tumors (20).

It is known that the receptors of the HER family are activated after binding to ligands or peptide growth factors (10, 12). Ligand binding induces clustering of HER family receptors and produces subsequent autophosphorylation of cytoplasmic tyrosine residues (10, 12). There are eleven HER ligands identified, and they can be divided in four groups based on the receptor binding specificity: a) exclusive EGFR binding: EGF, amphiregulin, TGF-α, and epigen; b) EGFR and Her4 binding: BTC, HB-EGFR and epiregulin; c) Her3 and Her4 binding: NRG1 and NRG2; and d) exclusive Her4 binding: NRG3 and NRG4 (10, 12). No ligand binding Her2 has been identified (10, 12). In our study, we examined the protein expression of eight out of nine ligands that bind to EGFR and Her3 receptors (10, 12). Of these, TGF-α (28, 29), epiregulin (30) and amphiregulin (31) have been shown to be frequently expressed in primary NSCLC tumors, and EGF, BTC, HB-EGF and NRG1 have been shown to expressed in NSCLC cell lines (32–34). However, none of them have been characterized in primary lung tumors and corresponding brain metastasis. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there is no report of the expression of NRG2 in lung cancer. We found that, compared with the corresponding primary tumors, NSCLC brain metastases had significantly higher immunohistochemical expression of membrane and nuclear EGF and of nuclear amphiregulin—ligands associated with activation of EGFR dimmers (10). These findings are consistent with the concomitant high level of overexpression of p-EGFR in the NSCLC brain metastasis that we studied and indicate the presence of an autocrine secretion mechanism of these ligands. In contrast to EGF and amphiregulin, the cytoplasmic expression of TGF-α and NGFR1, which bind to EGFR and Her3 receptors, respectively (10, 12), was significantly higher in malignant cells from primary tumors than in cells from brain metastases. Overexpression of TGF-α has been associated with the metastatic potential of NSCLC (32) and colon cancer (35) cell lines in favoring modifications of the tumor microenvironment conducive to metastasis, such as increasing angiogenesis.

In our study, we have identified that six of ligands, EGF, amphiregulin, epiregulin, NRG1, and NRG2, and two receptors, p-EGFR and p-Her3, had nuclear expression in malignant NSCLC cells. There is evidence that TK receptors, as well as their ligands, translocate into the nucleus via receptor-mediated endocytosis for degradation or to be recycled back to the cell surface (36–40). However, it now seems clear that these complexes reach into the cell nucleus where participate directly in the control of cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and cell survival (40).

The current concept of metastasis development states that metastases are the result of tumor cells interacting with a specific organ microenvironment, also called the “seed and soil” hypothesis (41). Thus, the microenvironments of different organs, including the brain, are biologically unique and can explain the expression of HER receptors and ligands in the brain metastasis tissue specimens differing from expression in the corresponding primary lung tumors. In addition, these observations have important implications for the development of molecularly targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. The fact that potential therapeutic targets (EGF, amphiregulin, TGF-α, NRG1, EGFR, and Her3) are expressed differently in metastases from corresponding primary tumors suggests that different molecular properties among tumor sites may influence differing responses to treatment and affect the levels of biomarkers that may be predictive of the response to treatment. Although immunohistochemical testing of EGFR has been shown not to be an optimal method for identifying patients who may respond to treatment with anti-EGFR drugs (16), there are preliminary data suggesting that the expression in tumor tissue of Her3 (15), amphiregulin (42), and TGF-α (31) correlates with sensitivity and resistance to EGFR TKI therapy. The immunohistochemical overexpression of Her3 in NSCLC tissue specimens has been correlated with EGFR TKI sensitivity (15). In contrast, increased expression of amphiregulin and TGF-α has been correlated with resistance to such therapy (31). In breast cancer, the transmembrane expression of neuroregulin has been correlated with improved survival in patients treated with Her-2 inhibitor (43).

An increase in EGFR gene copy number, including high polysomy and gene amplification (as shown by FISH), has been detected in 22% of patients with surgically resected (stages I–IIIA) NSCLC (21). Higher frequencies (40%–50%) of EGFR high copy number have been reported in patients with more-advanced metastatic NSCLC (stage IV) (44–48). In the present study, we have identified even a higher frequency (62%) of gain in EGFR copy number in surgically resected primary NSCLC specimens from patients who developed brain metastases. Recently, we reported that a gain in EGFR gene copy number was detected in 74% of primary NSCLC tumors from patients who developed brain metastasis (25). Altogether, these data suggest a stepwise increase in the frequency of gain in EGFR copy number in primary tumors with increasing tumor stage and, more important, with the development of brain metastasis. Interestingly, in our cases the presence of EGFR amplification, along with membrane EGFR protein overexpression, was significantly correlated with shorter time to brain metastasis development in the univariate analysis, further suggesting the important role of this genetic abnormality in the progression and metastasis of NSCLC.

Recently, we (20) and others (49) have shown that EGFR copy number gain, and specifically gene amplification, is a late phenomenon in the development of lung adenocarcinoma, appearing at invasive tumor stages and progressing in lymph node metastases, and that it is preceded by gene mutation. In the present study, we have expanded some of these observations to NSCLC brain metastasis. Although it was not statistically significant, we found that brain metastases of lung adenocarcinomas had a higher frequency of EGFR amplification than the corresponding primary tumors (30% versus 10%). Although a relatively high level (84%) of concordance for gain in EGFR copy number (when high polysomy and amplification were analyzed together) was detected when primary tumors and metastases were compared, there were 9 discordant cases (16%), including 6 brain metastases that had increased copy numbers while primary tumors did not. In contrast, we found that EGFR gene amplification had a low level of concordance (33%) when primary and metastatic tumors were compared, indicating a high level of heterogeneity for this phenomenon. The distinct rate of EGFR gene amplification between primary tumors and corresponding brain metastases may support the influence of this phenomenon on differing responses to treatment and may impact the assessment of this specific biomarker for anti-EGFR therapy.

The low frequency of EGFR mutations in exons 19 and 21 detected in our series of 42 primary NSCLC and corresponding metastases examined, including 30 adenocarcinomas, did not allow us to compare differences between both tumor sites. The single case having EGFR mutation (exon 19, point mutation) in the primary tumor showed identical mutation in the metastasis. The concordance on EGFR mutation between primary tumors and brain metastases has been previously reported in NSCLC in Japanese patients (50).

In summary, our findings indicate that NSCLC brain metastases exhibit important differences in abnormalities related to the HER family receptors from primary lung tumors. These differences may cause different responses to EGFR and other HER receptor targeted therapy of primary and metastatic tumor sites, and suggest that the site of origin (primary versus metastasis) of the tumor specimen should be factored into the biomarker analyses in the clinical trials testing the efficacy of HER receptors inhibitor in patients with metastatic NSCLC. Although our series of cases is relatively small and restricted to one metastatic site per patient, the data strongly suggest that the analysis of both primary and metastasis tumor sites may be critical for the identification of novel therapeutic targets and corresponding predictive biomarkers in lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Brain metastasis occurs in up to 60% of non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC) and there is little information on the molecular differences between primary tumor and metastases. Our findings indicate that NSCLC brain metastases have some significant differences in HER family receptors-related abnormalities from primary lung tumors. These differences could be related to tumor progression and may cause diverse responses to EGFR and other HER receptors-targeted therapy of primary and metastatic tumor sites.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant from the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-05-0027).

References

- 1.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. Tumours of the lung. In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, editors. Pathology and Genetics: Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2004. pp. 9–124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuschke M, Eberhardt W, Pottgen C, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after multimodality treatment: long-term follow-up and investigations of late neuropsychologic effects. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2700–2709. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omuro AM, Kris MG, Miller VA, et al. High incidence of disease recurrence in the brain and leptomeninges in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma after response to gefitinib. Cancer. 2005;103:2344–2348. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mamon HJ, Yeap BY, Janne PA, et al. High risk of brain metastases in surgically staged IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1530–1537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AM, Jahan TM, Jablons DM, Garcia J, Larson DA. Risk of cerebral metastases and neurological death after pathological complete response to neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer: clinical implications for the subsequent management of the brain. Cancer. 2007;109:1668–1675. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabel A, Debus J. Treatment of brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): radiotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2004;45(Suppl 2):S247–S252. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.07.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lester JF, MacBeth FR, Coles B. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for preventing brain metastases in patients undergoing radical treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer: a Cochrane Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch TJ, Bonomi PD, Butts C, et al. Novel agents in the treatment of lung cancer: Fourth Cambridge Conference. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:s4583–S4588. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst RS. Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Luca A, Carotenuto A, Rachiglio A, et al. The role of the EGFR signaling in tumor microenvironment. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:559–567. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montero JC, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Ocana A, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Esparis-Ogando A, Pandiella A. Neuregulins and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3237–3241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Z, Brdlik C, Jin P, Shepard HM. A pan-HER approach for cancer therapy: background, current status and future development. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:97–110. doi: 10.1517/14712590802630427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sequist LV, Lynch TJ. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer: an evolving story. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:429–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.090506.202405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst RS, Bunn PA., Jr. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5813–5824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimoto N, Wislez M, Zhang J, et al. High expression of ErbB family members and their ligands in lung adenocarcinomas that are sensitive to inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11478–11485. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuzzo F, Ardizzoni A, Soto-Parra H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeted therapy by ZD 1839 (Iressa) in patients with brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2003;41:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namba Y, Kijima T, Yokota S, et al. Gefitinib in patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: review of 15 clinical cases. Clin Lung Cancer. 2004;6:123–128. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2004.n.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mountain CF. Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest. 1997;111:1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang X, Varella-Garcia M, Xavier AC, et al. EGFR abnormalities in the pathogenesis and progression of lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:404–408. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr., et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3798–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrick DT, Kittelson J, Winterhalder R, et al. Analysis of c-ErbB1/epidermal growth factor receptor and c-ErbB2/HER-2 expression in bronchial dysplasia: evaluation of potential targets for chemoprevention of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2281–2288. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsao AS, Tang XM, Sabloff B, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of the EGFR gene mutation in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s1556-0864(15)31573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varella-Garcia M. Stratification of non-small cell lung cancer patients for therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: the EGFR fluorescence in situ hybridization assay. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2890–2896. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang X, Shigematsu H, Bekele BN, et al. EGFR tyrosine kinase domain mutations are detected in histologically normal respiratory epithelium in lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7568–7572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rusch V, Klimstra D, Venkatraman E, Pisters PW, Langenfeld J, Dmitrovsky E. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligand transforming growth factor alpha is frequent in resectable non-small cell lung cancer but does not predict tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volante M, Saviozzi S, Rapa I, et al. Epidermal growth factor ligand/receptor loop and downstream signaling activation pattern in completely resected nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1321–1328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Iwanaga K, Choi KC, et al. Intratumoral epiregulin is a marker of advanced disease in non-small cell lung cancer patients and confers invasive properties on EGFR-mutant cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:201–207. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakiuchi S, Daigo Y, Ishikawa N, et al. Prediction of sensitivity of advanced non-small cell lung cancers to gefitinib (Iressa, ZD1839) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3029–3043. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu W, O'Reilly MS, Langley RR, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF)/transforming growth factor-alpha by human lung cancer cells determines their response to EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition in the lungs of mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2652–2663. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandes AM, Hamburger AW, Gerwin BI. Production of epidermal growth factor related ligands in tumorigenic and benign human lung epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 1999;142:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gollamudi M, Nethery D, Liu J, Kern JA. Autocrine activation of ErbB2/ErbB3 receptor complex by NRG-1 in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasaki T, Nakamura T, Rebhun RB, et al. Modification of the primary tumor microenvironment by transforming growth factor alpha-epidermal growth factor receptor signaling promotes metastasis in an orthotopic colon cancer model. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:205–216. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpenter G. Nuclear localization and possible functions of receptor tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson HM, Subramaniam PS, Olsnes S, Jans DA. Trafficking and signaling pathways of nuclear localizing protein ligands and their receptors. Bioessays. 2004;26:993–1004. doi: 10.1002/bies.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krolewski JJ. Cytokine and growth factor receptors in the nucleus: what's up with that? J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:478–487. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massie C, Mills IG. The developing role of receptors and adaptors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:403–409. doi: 10.1038/nrc1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. Nuclear signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases: the first robin of spring. Cell. 2006;127:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the 'seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Lindeman N, et al. Autocrine production of amphiregulin predicts sensitivity to both gefitinib and cetuximab in EGFR wild-type cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6963–6973. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Alava E, Ocana A, Abad M, et al. Neuregulin expression modulates clinical response to trastuzumab in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2656–2663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, McCoy J, et al. Increased Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Gene Copy Number Detected by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Associates With Increased Sensitivity to Gefitinib in Patients With Bronchioloalveolar Carcinoma Subtypes: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackman DM, Holmes AJ, Lindeman N, et al. Response and resistance in a non-small-cell lung cancer patient with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and leptomeningeal metastases treated with high-dose gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4517–4520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bunn PA, Jr., Dziadziuszko R, Varella-Garcia M, et al. Biological markers for non-small cell lung cancer patient selection for epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3652–3656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yatabe Y, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification is acquired in association with tumor progression of EGFR-mutated lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2106–2111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto S, Takahashi K, Iwakawa R, et al. Frequent EGFR mutations in brain metastases of lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1491–1494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.