Abstract

Studies published between 1986 and 1999 indicated that rotavirus causes ≈22% (range 17%–28%) of childhood diarrhea hospitalizations. From 2000 to 2004, this proportion increased to 39% (range 29%–45%). Application of this proportion to the recent World Health Organization estimates of diarrhea-related childhood deaths gave an estimated 611,000 (range 454,000–705,000) rotavirus-related deaths.

Keywords: Diarrhea, rotavirus, mortality, morbidity, hospitalizations, disease burden, dispatch

Rotavirus is the leading cause of diarrhea hospitalization among children worldwide (1). In 2003, we published an estimate of rotavirus-related deaths worldwide based on a review of the literature published from 1986 through 1999 on deaths caused by diarrhea and rotavirus hospitalizations in children (2). This review indicated that rotavirus accounted for ≈22% of hospitalizations for childhood diarrhea. By applying this fraction to an estimate of 2.1 million annual deaths from diarrhea, we calculated that rotavirus causes 440,000 annual deaths in children <5 years of age worldwide. This estimate was ≈50% of the 1985 estimate of 873,000 rotavirus deaths per year (3), and the decrease in estimated rotavirus-related deaths paralleled the decrease in deaths from diarrhea of all causes from an estimated 4.6 million deaths in 1982 to 1.6–2.5 million deaths in 2000 (4–6).

Recent studies suggest that as global deaths from childhood diarrhea decreased during the past 2 decades, the proportion of diarrhea hospitalizations attributable to rotavirus may have increased. For example, prospective, sentinel hospital–based surveillance of rotavirus disease in 9 Asian countries demonstrated a median rotavirus detection of 45% among children hospitalized with diarrhea (7), a figure that was considerably greater than the detection rates in previous studies from the same countries. Similarly, a more extensive study of 5,768 children hospitalized from 1998 through 2000 in 6 centers in Vietnam identified rotavirus in 56% of patients (8), a proportion that was more than twice the 21% detection rate reported among children hospitalized with diarrhea in a hospital in Hanoi, Vietnam, from 1981 to 1984 (9).

To systematically evaluate whether these recent reports are isolated observations or reflect a changing trend in the etiology of childhood diarrhea hospitalizations, we reviewed studies of rotavirus detection among children hospitalized with diarrhea published from 2000 through 2004 and compared the data with those of the previous review of studies published from 1986 through 1999.

The Study

Similar to the approach used in our previous review, we performed a computer search of the scientific literature (in English and other languages) published from January 2000 through June 2004 using the words rotavirus and the truncated stem rota-. We restricted the analysis to studies that met the following criteria: 1) were initiated after 1993; 2) were conducted for at least 1 full calendar year; and 3) examined rotavirus among at least 100 children <5 years of age hospitalized with diarrhea.

For each study, we determined the proportion of cases positive for rotavirus among children hospitalized with diarrhea. We plotted this proportion against the per capita gross national product (GNP) for the country in which the study was conducted. We then classified countries by per capita GNP into World Bank income groups (low, <US $756; low-middle, US $756–$2,995; high-middle, US $2,996–$9,265; and high, >US $9,265) (10), and calculated the median (interquartile range [IQR]) proportion of diarrhea hospitalizations attributable to rotavirus for each income group.

We next calculated an overall median detection rate by taking a weighted average of the median detection rates for each of the income groups. The weights assigned to each income group corresponded to the proportion of deaths from childhood diarrhea among countries in that income group as determined on the basis of our previous analysis (2): 85% in low-income countries, 13% in low-middle–income countries, 2% in high-middle–income countries, and <1% in high-income countries. To estimate deaths from rotavirus disease among children, we multiplied the overall median detection rate of rotavirus among children hospitalized with diarrhea by a recent World Health Organization estimate of deaths from diarrhea among children worldwide (5).

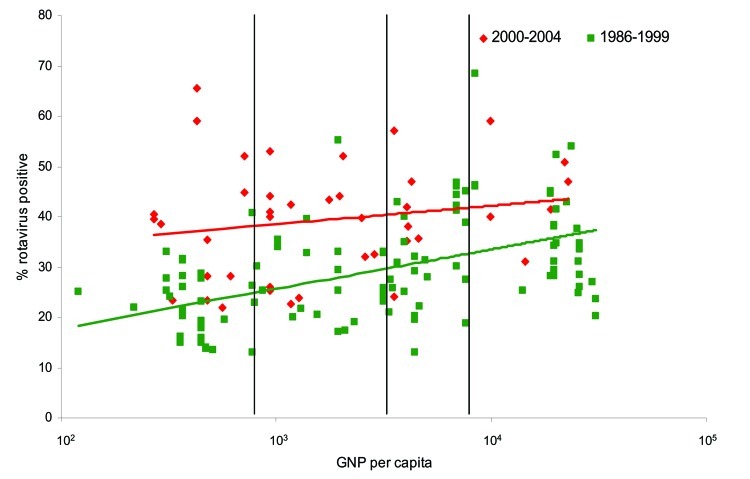

We abstracted information from 41 studies that met all the inclusion criteria (Table A1). Unlike the previous review of studies conducted for the period 1986–1999, in which the proportion of diarrhea-related hospitalizations attributable to rotavirus showed a distinct increasing trend with increasing income level, we found that the median detection rates increased only slightly with increasing income level (Figure 1). The median detection rate for rotavirus among children hospitalized with diarrhea was 39% in studies conducted in low-income countries, 40% for low-middle–income countries, 38% for high-middle–income countries, and 44% for high-income countries, for an overall weighted median estimate of 39% (Table).

Figure 1.

Percentage of severe diarrhea cases attributable to rotavirus for countries in different World Bank income groups, by per capita gross national product (GNP), for studies published in 1986–1999 and 2000–2004. GNP is in US dollars. Upper line, trend for 2000–2004; lower line, trend for 1986–1999.

Table. Percentage of diarrhea hospitalizations attributable to rotavirus for countries in different World Bank income groups, 1986–1999 and 2000–2004.

| Income group | Median % (interquartile range) of diarrhea-associated hospitalizations due to rotavirus |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1986–1999 | 2000–2004 | |

| Low | 20 (16–27) | 39 (28–45) |

| Low middle | 25 (20–33) | 40 (32–43) |

| High middle | 31 (25–42) | 38 (35–45) |

| High | 34 (28–38) | 44 (40–50) |

| Total* | 21 (17–28) | 39 (29–45) |

*The overall median was calculated by taking a weighted average of the median rotavirus detection rate for each income group. The weights applied to each group corresponded to that group's proportion of global diarrheal deaths: 85% for low-income countries, 13% for low-middle–income countries, 2% for high-middle–income countries, and <1% for high-income countries.

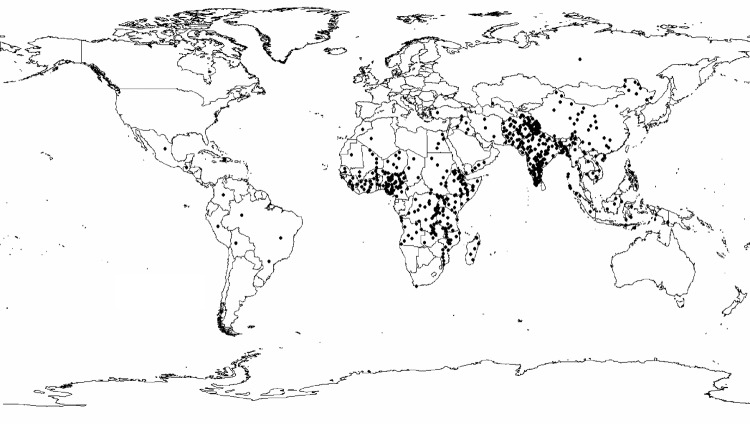

If we multiply the greater median rotavirus detection rate of 39% (IQR 29%–45%) from this analysis by 1,566,000 recently estimated childhood diarrhea deaths (5), we find that rotavirus causes ≈611,000 childhood deaths (IQR 454,000–705,000). More than 80% of all rotavirus-related deaths were estimated to occur in low-income countries of south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated global distribution of rotavirus-related deaths. Each dot represents 1,000 rotavirus-related deaths.

Conclusions

Compared with results from studies published from 1986 to 1999, the proportion of diarrhea hospitalizations attributable to rotavirus appears to have increased between 2000 and 2004. This phenomenon likely reflects a relatively slower rate of decrease in hospitalizations for rotavirus compared with other causes of severe childhood diarrhea. This finding could be accounted for by several factors. First, interventions to improve hygiene and sanitation are likely to have a greater impact on diarrhea caused by bacterial and parasitic agents, which are transmitted primarily through contaminated food or water, unlike rotavirus, which is often spread from person-to-person. This hypothesis is supported by data from the United States (11) and Mexico (12), which showed that as diarrhea-related childhood deaths decreased dramatically in both countries; the decrease was greatest during the summer months when diarrheal diseases caused by bacteria are more prevalent. In both countries, diarrhea-related deaths in recent years have exhibited peaks only in the winter when rotavirus infections are common. Second, oral hydration therapy to replace loss of body fluids, which many regard as a major factor responsible for the decrease in diarrhea deaths (13), is often more difficult to successfully administer in children with severe vomiting (14), a common manifestation of rotavirus disease. Third, unlike antimicrobial therapies that are effective against some bacterial and parasitic agents, no specific treatment for rotavirus infection is available.

We have derived preliminary updated estimates of rotavirus-related childhood deaths on the basis of the findings of our review. Because we wanted to assess the most recent trends in rotavirus incidence, we examined a relatively limited number of studies published in the last 5 years, particularly from upper-middle– and high-income countries. However, these 2 income groups account for only a small fraction (<5%) of all deaths from rotavirus disease, and the 28 studies available from low- and low-middle–income countries allowed for a reasonably robust analysis. Nevertheless, our findings should be updated as new data on rotavirus hospitalizations and updated estimates of childhood diarrhea deaths become available. In 2002, the World Health Organization published a generic protocol for hospital-based surveillance of rotavirus (15), and studies using this protocol are currently being conducted or planned in >30 countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Data from these and other studies, particularly from countries such as India and China, which account for a large fraction of global rotavirus deaths, should be used to update our estimate of rotavirus-related deaths and further refine it to develop country-specific figures. These data, together with information on effects and costs of rotavirus disease, will allow policymakers to assess the magnitude of the problem of rotavirus and the value of new vaccines that may soon be available.

References

Biography

Dr Parashar is a medical epidemiologist with the Respiratory and Enteric Viruses Branch, Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. His research focuses on the epidemiology of viral gastroenteritis and respiratory infections and methods for their prevention and control.

Table A1. Characteristics of studies on worldwide diarrheal deaths and hospitalizations, 2000–2004.

| Income group and country | Year of publication | Study period | No. diarrhea hospitalizations | Rotavirus detection rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | |||||

| Cameroon | 2003 | 1999–2000 | 890 | 21.9 | 16 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2003 | 1997–1999 | 479 | 28.3 | 17 |

| Ghana | 2003 | 1997–2002 | 2,205 | 40.5 | 18 |

| Ghana | 2003 | 1998–2000 | 1,717 | 39.4 | 19 |

| India | 2004 | 2001 | 401 | 35.5 | 20 |

| India | 2001 | 1993–1996 | 628 | 28.3 | 21 |

| India | 2003 | 1999–2000 | 202 | 23.3 | 22 |

| Indonesia | 2004 | 2001–2002 | 577 | 52.0 | 23 |

| Indonesia | 2002 | 1997–1999 | 339 | 44.8 | 24 |

| Nigeria | 2003 | 1998–1999 | 417 | 38.6 | 17 |

| Vietnam | 2004 | 2001–2002 | 1,570 | 59.0 | 23 |

| Vietnam | 2003 | 1999–2000 | 1,355 | 65.6 | 25 |

| Zambia | 2003 | 1997–1999 | 1,635 | 23.3 | 17 |

| Low-middle | |||||

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 2003 | 1999–2000 | 201 | 23.9 | 26 |

| Brazil | 2001 | 1998–1999 | 190 | 32.6 | 27 |

| China | 2004 | 2001–2002 | 2,079 | 44.0 | 23 |

| China | 2000 | 1996–1999 | 1,130 | 26.1 | 28 |

| China | 2002 | 1998–2000 | 3,177 | 41.0 | 29 |

| China | 2003 | 1998–2001 | 1,211 | 52.9 | 30 |

| China | 2004 | 1999–2001 | 1,230 | 40.1 | 31 |

| Jordan | 2002 | 1997–2000 | 840 | 43.4 | 32 |

| Paraguay | 2003 | 1998–2000 | 410 | 22.7 | 33 |

| Paraguay | 2002 | 1999–2000 | 141 | 42.5 | 34 |

| Peru | 2001 | 1995–1997 | 386 | 52.0 | 35 |

| South Africa | 2003 | 1997–1999 | 1,525 | 32.0 | 17 |

| Thailand | 2004 | 2001–2002 | 992 | 44.0 | 23 |

| Turkey | 2003 | 2000–2001 | 920 | 39.8 | 36 |

| High-middle | |||||

| Argentina | 2001 | 1996–1998 | 1,312 | 42.0 | 37 |

| Argentina | 2001 | 1997–1998 | 133 | 35.3 | 38 |

| Chile | 2001 | 1997–1999 | 276 | 47.0 | 39 |

| Malaysia | 2004 | 2001–2002 | 1,374 | 57.0 | 23 |

| Malaysia | 2003 | 1996–1999 | 1,362 | 24.0 | 40 |

| Poland | 2000 | 1997 | 773 | 35.6 | 41 |

| Venezuela | 2001 | 1997–1999 | 946 | 38.0 | 39 |

| High | |||||

| France | 2002 | 1997–2000 | 706 | 50.9 | 42 |

| Germany | 2003 | 2001–2002 | 217 | 47.0 | 43 |

| Italy | 2002 | 2001 | 330 | 41.4 | 44 |

| South Korea | 2000 | 1998–1999 | 243 | 40.0 | 45 |

| South Korea | 2003 | 1998–2000 | 348 | 59.0 | 46 |

| Spain | 2004 | 1998–2002 | 3,760 | 31.0 | 47 |

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresee JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2006 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1202.050006

References

- 1.Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Gentsch JR, Glass RI. Rotavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:561–70. 10.3201/eid0404.980406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, Miller MA, Glass RI. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565–72. 10.3201/eid0905.020562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The prospects of immunizing against rotavirus. In: New vaccine development: diseases of importance in developing countries. Washington: National Academy Press; 1986. p. D13-1–D13-12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder JD, Merson MH. The magnitude of the global problem of acute diarrhoeal disease: a review of active surveillance data. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:605–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The world health report 2003: shaping the future. Geneva: The Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresee J, Fang ZY, Wang B, Nelson EAS, Tam J, Soenarto Y, et al. First report from the Asian Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Man N, Van Trang N, Lien HP, Parch DD, Thanh NTH, Tu PV, et al. The epidemiology and disease burden of rotavirus in Vietnam: sentinel surveillance at 6 hospitals. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1707–12. 10.1086/320733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doan TN, Nguyen VC. Preliminary study on rotavirus diarrhoea in hospitalized children at Hanoi. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1986;4:81–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank Group. Classification of economies by income. 2000. [cited 2004 July 16]. Available from http://www.worldbank.org/data/countryclass/classgroups.htm

- 11.Kilgore PE, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, Glass RI. Trends of diarrheal disease: associated mortality in US children, 1968 through 1991. JAMA. 1995;274:1143–8. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530140055032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villa S, Guiscafre H, Martinez H, Munoz O, Guiterrez G. Seasonal diarrhoeal mortality among Mexican children. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:375–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R. Reducing deaths from diarrhea through oral rehydration therapy. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1246–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed FU, Karim E. Children at risk of developing dehydration from diarrhoea: a case-control study. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48:259–63. 10.1093/tropej/48.5.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bresee J, Parashar U, Holman R, Gentsch J, Glass R, Ivanoff B, et al. Generic protocol for hospital-based surveillance to estimate the burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age. In: Generic protocols for (i) hospital-based surveillance to estimate the burden of gastroenteritis in children and (ii) a community-based survey on utilization of health care services for gastroenteritis in children; field test version (WHO/V&B/02.15). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. p. 1–44. Also available from http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/rotavirus/documents/en

- 16.Esona MD, Armah GE, Steele AD. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus infection in Western Cameroon. J Trop Pediatr. 2003;49:160–3. 10.1093/tropej/49.3.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele AD, Ivanoff B. Rotavirus strains circulating in Africa during 1996–1999: emergence of G9 strains and P[6] strains. Vaccine. 2003;21:361–7. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00616-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armah GE, Steele AD, Binka FN, Esona MD, Asmah RH, Anto F, et al. Changing patterns of rotavirus genotypes in Ghana: emergence of human rotavirus G9 as a major cause of diarrhea in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2317–22. 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2317-2322.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binka FN, Anto FK, Oduro AR, Awini EA, Nazzar AK, Armah GE, et al. Incidence and risk factors of paediatric rotavirus diarrhoea in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:840–6. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das S, Varghese V, Chaudhuri S, Barman P, Kojima K, Dutta P, et al. Genetic variability of human rotavirus strains isolated from Eastern and Northern India. J Med Virol. 2004;72:156–61. 10.1002/jmv.10542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelkar SD, Purohit SG, Boralkar AN, Verma SP. Prevalence of rotavirus diarrhea among outpatients and hospitalized patients: a comparison. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:494–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phukan AC, Patgiri DK, Mahanta J. Rotavirus associated acute diarrhoea in hospitalized children in Dibrugarh, north-east India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:274–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bresee J, Fang ZY, Wang B, Nelson EA, Tam J, Soenarto Y, et al. First report from the Asian Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subekti D, Lesmana M, Tjaniadi P, Safari N, Frazier E, Simanjuntak C, et al. Incidence of Norwalk-like viruses, rotavirus and adenovirus infection in patients with acute gastroenteritis in Jakarta, Indonesia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;33:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doan LT, Okitsu S, Nishio O, Pham DT, Nguyen DH, Ushijima H. Epidemiological features of rotavirus infection among hospitalized children with gastroenteritis in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Med Virol. 2003;69:588–94. 10.1002/jmv.10347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmetagic S, Jusufovic E, Petrovic J, Stojic V, Delibegovic Z. Acute infectious diarrhea in children. Med Arh. 2003;57:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.da Rosa e Silva ML. Naveca FG, Pires de Carvalho I. Epidemiological aspects of rotavirus infections in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2001;5:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang ZY, Yang H, Zhang J, Li YF, Hou AC, Ma L, et al. Child rotavirus infection in association with acute gastroenteritis in two Chinese sentinel hospitals. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:401–5. 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang ZY, Yang H, Qi J, Zhang J, Sun LW, Tang JY, et al. Diversity of rotavirus strains among children with acute diarrhea in China: 1998–2000 surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1875–8. 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1875-1878.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun LW, Tong ZL, Li LH, Zhang J, Chen Q, Zheng LS, et al. Surveillance finding on rotavirus in Changchun children's hospital during July 1998-June 2001. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24:1010–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng M, Zhu QR, Zhang Y, Li GH, Chen DM, Ding YX, et al. Molecular epidemiologic survey of rotaviruses from infants and children with diarrhea in Shanghai. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2004;42:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battikhi MN. Epidemiological study on Jordanian patients suffering from diarrhoea. New Microbiol. 2002;25:405–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Candia N, Parra GI, Chirico M, Velazquez G, Farina N, Laspina F, et al. Acute diarrhea in Paraguayan children population: detection of rotavirus electropherotypes. Acta Virol. 2003;47:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coluchi N, Munford V, Manzur J, Vazquez C, Escobar M, Weber E, et al. Detection, subgroup specificity, and genotype diversity of rotavirus strains in children with acute diarrhea in Paraguay. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1709–14. 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1709-1714.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cama RI, Parashar UD, Taylor DN, Hickey T, Figueroa D, Ortega YR, et al. Enteropathogens and other factors associated with severe disease in children with acute watery diarrhea in Lima, Peru. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1139–44. 10.1086/314701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurugol Z, Geylani S, Karaca Y, Umay F, Erensoy S, Vardar F, et al. Rotavirus gastroenteritis among children under five years of age in Izmir, Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2003;45:290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bok K, Castagnaro N, Borsa A, Nates S, Espul C, Fay O, et al. Surveillance for rotavirus in Argentina. J Med Virol. 2001;65:190–8. 10.1002/jmv.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giordano MO, Ferreyra LJ, Isa MB, Martinez LC, Yudowsky SI, Nates SV. The epidemiology of acute viral gastroenteritis in hospitalized children in Cordoba City, Argentina: an insight of disease burden. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43:193–7. 10.1590/S0036-46652001000400003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Ryan M, Perez-Schael I, Mamani N, Pena A, Salinas B, Gonzalez G, et al. Rotavirus-associated medical visits and hospitalizations in South America: a prospective study at three large sentinel hospitals. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:685–93. 10.1097/00006454-200107000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee WS, Veerasingam PD, Goh AY, Chua KB. Hospitalization of childhood rotavirus infection from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:518–22. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rytlewska M, Bako W, Ratajczak B, Marek A, Gwizdek A, Czarnecka-Rudnik D, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of rotaviral diarrhoea in children from Gdansk, Gdynia and Sopot. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moulin F, Marc E, Lorrot M, Coquery S, Sauve-Martin H, Ravilly S, et al. Hospitalization for acute community-acquired rotavirus gastroenteritis: a 4-year survey. Arch Pediatr. 2002;9:255–61. 10.1016/S0929-693X(01)00761-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh DY, Gaedicke G, Schreier E. Viral agents of acute gastroenteritis in German children: prevalence and molecular diversity. J Med Virol. 2003;71:82–93. 10.1002/jmv.10449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crotti D, d'Annibale ML, Fonzo G, Medori MC, Ubaldi M. Enteric infections in Perugia's area: laboratory diagnosis, clinical aspects and epidemiology during 2001. Infez Med. 2002;10:81–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seo JK, Sim JG. Overview of rotavirus infections in Korea. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:406–10. 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song MO, Kim KJ, Chung SI, Lim I, Kang SY, An CN, et al. Distribution of human group a rotavirus VP7 and VP4 types circulating in Seoul, Korea between 1998 and 2000. J Med Virol. 2003;70:324–8. 10.1002/jmv.10398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanchez-Fauquier A, Wilhelmi I, Colomina J, Cubero E, Roman E. Diversity of group A human rotavirus types circulating over a 4-year period in Madrid, Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1609–13. 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1609-1613.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]