Abstract

The transfer of the genomic resources developed in the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, to other Tilapiines sensu lato and African cichlid would provide new possibilities to study this amazing group from genetics, ecology, evolution, aquaculture, and conservation point of view. We tested the cross-species amplification of 32 O. niloticus microsatellite markers in a panel of 15 species from 5 different African cichlid tribes: Oreochromines (Oreochromis, Sarotherodon), Boreotilapiines (Tilapia), Chromidotilapines, Hemichromines, and Haplochromines. Amplification was successfully observed for 29 markers (91%), with a frequency of polymorphic (P95) loci per species around 70%. The mean number of alleles per locus and species was 3.2 but varied from 3.7 within Oreochromis species to 1.6 within the nontilapia species. The high level of cross-species amplification and polymorphism of the microsatellite markers tested in this study provides powerful tools for a wide range of molecular genetic studies within tilapia species as well as for other African cichlids.

1. Introduction

African cichlid fish are of extreme interest for both evolutionary biology and applied genetics purposes, including amazing models for speciation, adaptation, behaviour and neurosciences [1–5] as well as groups of major importance for aquaculture and fisheries (strain selection and improvement, stock assessment, etc.) [6–10]. A wide range of structural and functional genomic resources have been developed for cichlids in the past 15 years, predominantly in the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus [11–14]. While genome sequencing projects are in progress for several African cichlids, the transfer of genomic resources from O. niloticus across the entire group of tilapias sensu lato as well as other African cichlid tribes would provide powerful tools to support a wide range of evolutionary biology studies, including comparative phylogenetics, genome mapping, evolution of gene family sequence and expression, candidate gene analyses for adaptation, and population genetics.

Microsatellite markers are one of the most interesting resources to transfer across lineages, as they can provide numerous locus-specific molecular markers and putatively homologous sequences across taxa. In addition to their high level of polymorphism, the evolutionary conservation of the flanking region of microsatellite loci allows large-scale heterospecific amplification [15, 16], as previously shown in various animal groups, particularly fish [17–19]. However, the rate of cross-species amplification varies widely among taxonomic groups and loci [18, 20]. In addition to their application in population genetics, conserved microsatellite markers are particularly useful for population, species or hybrid identification (especially at early developmental stages) and candidate-marker analysis, comparative genetic mapping, and QTL analysis. Furthermore, compared to anonymous multilocus genomic markers (RFLP, AFLP, ISSR) and SNPs, microsatellites present the important advantages of (i) being highly reproducible and very easily transferable between laboratory (with limited equipment and computational requirement), (ii) providing a high polymorphism information contain (PIC) per locus, and (iii) being highly cost efficient when only a small number of loci are needed. For these reasons, microsatellites markers are likely to remain popular for a wide range of ecology and evolutionary studies (e.g., relatedness and parentage analysis, population diversity and demography assessment, noninvasive genetic analysis, and conservation).

Since the first publication of microsatellite markers cloned in O. niloticus [13], thousands have been published and more than 500 have been positioned onto the genetic map of O. niloticus and the closely related O. aureus [14, 21]. These microsatellites have been used to map traits of interest, such as sex determination factors [22, 23], and have also been found to influence the expression of genes associated to physiological adaptation [24].

Outside the tilapias, microsatellite markers have been developed in a few different Haplochromines species: Copadichromis cyclicos [25], Tropheus moorii [19], Pseudotropheus zebra [26], Astatoreochromis alluaudi [27], Pundamilia pundamilia [28], Metriaclima zebra [29], Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor [30], Paralabidochromis chilotes [31], and Astatotilapia burtoni [32]. However these studies reported a smaller number of markers than that in Nile tilapia. The use of microsatellite markers in Haplochromines has been almost strictly restricted to descriptive population genetics and parentage/relatedness analysis, which represent only a subset of the possibilities offered by having a large set of genome-anchored microsatellite markers, as available for O. niloticus.

Additionally, microsatellites developed outside tilapias were derived exclusively from the most species-rich group of African cichlids and there are very limited genomic resources in all the other “under-studied” African cichlid tribes [33–35].

Considering the central position occupied by the Tilapiines sensu lato in the African cichlid phylogeny [38], their large diversity within at least 3 monophyletic clades [39–41], and the important number of species involved in population transfers, hybridisation, and/or invasion [8, 42], we decided to investigate the cross-species amplification efficiency of Nile tilapia microsatellites among the different groups of the Tilapiines sensu lato as well as three other African cichlid tribes, to extend the use/availability of this resource across a wide range of African cichlid species, including “under-studies” groups. The panel of species investigated then spans a large section of the African cichlid radiation, with an estimated overall divergence time of 33.4–63.7 Myrs [41, 43].

2. Material and Methods

Tests of cross-species amplification were conducted in a panel of 15 African cichlid species, representing all three major genera of Tilapiines sensu lato: 7 Oreochromis, 2 Sarotherodon, both genera belonging to the Oreochromines, and 3 Tilapia (Coptodon), belonging to the Boreotilapiines; as well as representatives of 3 other African cichlid tribes, including the derived Haplochromines, and two more basal tribes, the Chromidotilapiines and the Hemichromines (see details in Table 1). Analyses were conducted using 3 to 9 individuals per species (Table 1). Genomic DNA was extracted from fin clips stored in ethanol using a standard phenol-chloroform protocol [44].

Table 1.

Species studied for cross-species amplification tests, with geographic origin, and number of samples analysed per species.

| Lineages Genus Species | Geographic origin | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oreochromines | |||

| Oreochromis | |||

| O. (Oreochromis) niloticus | Bouake (Cote d'Ivoire)* | 9 | |

| O. (Oreochromis) aureus | Lake Manzala (Egypt) | 5 | |

| O. (Oreochromis) mossambicus | Mozambique | 5 | |

| O. (Oreochromis) shiranus | Lake Malawi | 5 | |

| O. (Nyasalapia) macrochir | Bouake (Cote d'Ivoire)** | 5 | |

| O. (Nyasalapia) saka | Lake Malawi | 5 | |

| O. (Nyasalapia) squamipinnis | Lake Malawi | 5 | |

| Sarotherodon | |||

| S. (Sarotherodon) galilaeus | Bamako (Niger) | 3 | |

| S. (Sarotherodon) melanotheron | Ébrié Lagoon (Ivory Cost) | 5 | |

| Boreotilapiines | |||

| Tilapia | |||

| T. (Coptodon) dageti | Bamako (Niger) | 5 | |

| T. (Coptodon) guineensis | Ivory Cost/Senegal | 4 | |

| T. (Coptodon) zillii | Lake Manzala (Egypt) | 5 | |

| Haplochromines | |||

| Haplochromis | |||

| Haplochromis sp. “rock kribensis” | Lake Victoria | 3 | |

| Chromidotilapines | |||

| Chromidotilapia | |||

| Chromidotilapia guntheri | Bamako (Niger) | 3 | |

| Hemichromines | |||

| Hemichromis | |||

| Hemichromis bimaculatus | Bandama (Ivory Cost) | 5 | |

The panel of 32 microsatellites was selected from the markers isolated in O. niloticus [13]. Genotyping was obtained by PCR amplification with radioactive (P33) labeled primers [44, 45]. Allele variants were separated on 6% acrylamide gel electrophoresis. For each marker, the annealing temperature and MgCl2 concentration were adjusted to optimise the efficiency of PCR amplification based on O. niloticus and two others species: one closely related among Oreochromis (O. mossambicus) and one distantly related among the Oreochromines (S. melanotheron). Cross-species amplifications were carried out using these conditions in the 15 studied species (Table 2). For each microsatellite marker, the amplification success has been estimated qualitatively on a 4-level scale based on the quality of the electrophoresis pattern across the test individuals (i.e., “++” for strong and sharp amplification pattern, “+” for good quality pattern with some stutters, echo-alleles or low intensity, “−” for high variance of amplification quality across individuals, very high level of stutter, and/or high frequency of null alleles, and “−−” very poor quality pattern, nonspecific or lack of, amplification). For each locus by species combination (n = 480), we assessed the amplification success and counted the number of different alleles among individuals. The presence of putative null alleles (i.e., nonamplified alleles) was inferred when a few individuals consistently showed an absence of allele amplification while other individuals from the same species showed high-quality amplification pattern or in the complete absence of heterozygous individuals. Echo-alleles (i.e., supplementary allele coamplifying across individuals producing amplification pattern consistently representing 2 or 4 alleles per individuals, with the longest allele separated from the shortest “cosegregating” allele by an identical length across individuals/alleles) were also identified. Furthermore, the rate of amplification success, the frequency of polymorphic loci (P95), and the mean number of allele per locus were calculated per species, genus, and tribe across all studied microsatellites markers.

Table 2.

Microsatellite loci tested for cross-species amplification with indications of repeat structure observed in O. niloticus (according to Lee and Kocher, [13]), allele size range of the amplified fragment across all tested species, PCR and electrophoresis conditions (labeled primer, annealing temperature/magnesium concentration (mM)/electrophoresis Volt-hour), and amplification quality obtained after PCR optimisation tests (from very good ++ to poor −−; see detail of the categories in main text); loci presenting a wide cross-species amplification efficiency are in bold.

| Loci | GenBank access No. | Structure | Range (bp) | PCR and electrophoresis conditions | Amplification efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNH-008 | G31346 | Perfect | 196–236 | R* 56/1.2/6000 | ++ |

| UNH-102 | G12255 | Perfect | 132–185 | R* 50/1.2/4500 | ++ |

| UNH-103 | G12256 | Perfect | 171–260 | R* 48/1.2/6000 | + |

| UNH-106 | G12259 | Compound | 115–189 | R* 50/1.2/3500 | + |

| UNH-115 | G12268 | Compound | 100–146 | F* 50/1.5/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-117 | G12270 | Interrupted | 108–146 | R* 5411.2/4500 | ++ |

| UNH-120 | G12273 | Compound | — | R* 48/2/— | − − |

| UNH-123 | G12276 | Perfect | 142–232 | F* 48/1.2/4500 | ++ |

| UNH-124 | G12277 | Perfect | 295–324 | F* 54/1.2/7500 | ++ |

| UNH-125 | G12278 | Compound | 134–198 | R* 48/1.5/4500 | + |

| UNH-129 | G12282 | Interrupted | 180–253 | R* 48/1.2/4500 | + |

| UNH-130 | G12283 | Perfect | 174–242 | R* 50/1.2/4500 | + |

| UNH-131 | G12284 | Perfect | 283–303 | F* 48/2/6000 | − |

| UNH-132 | G12285 | Perfect | 100–134 | R* 52/1.2/3500 | + |

| UNH-135 | G12287 | Interrupted | 124–284 | R* 50/1.5/4500 | + |

| UNH-138 | G12290 | Perfect | 144–250 | R* 48/1.5/4500 | + |

| UNH-142 | G12294 | Interrupted | 142–192 | F* 48/1.2/4500 | ++ |

| UNH-146 | G12298 | Interrupted | 111–149 | F* 60/1/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-149 | G12301 | Perfect | 143–225 | R* 48/1.5/4500 | + |

| UNH-154 | G12306 | Perfect | 98–176 | R* 50/1.2/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-159 | G12311 | Perfect | 205–267 | R* 55/1.2/6000 | ++ |

| UNH-162 | G12314 | Perfect | 125–252 | R* 48/1.5/6000 | ++ |

| UNH-169 | G12321 | Interrupted | 124–240 | R* 54/1.2/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-173 | G12325 | Perfect | 124–188 | F* 55/1.2/4500 | + |

| UNH-174 | G12326 | Perfect | 146–187 | F* 48/1.5/4500 | ++ |

| UNH-189 | G12341 | Perfect | 135–208 | R* 52/1.2/4500 | + |

| UNH-190 | G12342 | Compound | 133–202 | R* 60/1/4500 | + |

| UNH-193 | G12386 | Perfect | — | R* 48/2/3500 | − − |

| UNH-197 | G12348 | Interrupted | 154–228 | R* 50/1.2/4500 | + |

| UNH-207 | G12358 | Interrupted | 90–198 | R* 60/1.2/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-211 | G12362 | Perfect | 82–194 | R* 48/1.5/3500 | ++ |

| UNH-216 | G12367 | Perfect | 126–212 | R* 52/1.2/3500 | ++ |

3. Results and Discussion

Very high rates of microsatellite amplification and polymorphism were observed (both 97%), in the Nile tilapia, with a mean number of alleles per locus of 4.3. Across the 14 other test species, 29 loci gave good quality amplifications (91%-Tables 2 and 3), while 3 markers (9%) showed a high discrepancy of amplification efficiency and/or unclear amplification pattern (Table 2; see details in supplementary material which is available online at doi:10.1155/2012/870935: Table S1). Excluding the Nile tilapia, the average intraspecific rate of successful amplification and polymorphism across the panel of 32 markers was more than 70% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of cross-species amplification performed over the 32 tested microsatellite loci on the 15 African cichlid species studied, including amplification rate, polymorphism rate, and mean number of alleles per locus, estimated per genus and tribe.

| Groups | N species | Amplification rate | Polymorphism (P95) | Mean allele number per locus | % shared alleles per | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per group | Per species | |||||

| O. niloticus | 97% | 97% | — | 4.3 | — | |

|

| ||||||

| Oreochromis spp.* | 6 | 88% | 76% | 17.8 | 3.7 | 37% |

| Sarotherodon spp. | 2 | 86% | 85% | 6.4 | 3.3 | 9.2% |

| Tilapia spp. | 3 | 67% | 59% | 6 | 2.4 | 19.7% |

| Tilapiines* | 11 | 82% | 74% | 24.3 | 3.7 | 20.5% |

| non-Tilapiines | 3 | 34% | 36% | 3.4 | 1.6 | 2.3% |

| Haplochromines | 1 | 38% | 50% | — | 1.6 | — |

| Chromidotilapines | 1 | 47% | 20% | — | 1.4 | — |

| Hemichromines | 1 | 19% | 50% | — | 2.3 | — |

|

| ||||||

| Total* | 72% | 70% | 25.7 | 3.2 | 5.3% | |

*Excluding O. niloticus.

The expected relationship between the success of cross-species amplifications and evolutionary distance from marker cloning species [15, 20] was observed, reflecting the phylogenetic relationships between the different groups of African cichlids [39–41] (Table 3; see details in supplementary material: Table S2). Within the Tilapiines sensu lato, species from both mouth-brooder genera (i.e., Oreochromis and Sarotherodon), constitutive of the monophyletic clade of the Oreochromines diverged 12.8–21.4 Myrs ago, showed very high and similar amplification (88% and 86%, resp.) and polymorphism (76% and 85%, resp.) rates, whereas species from the genus Tilapia, belonging to the Boreotilapiines with a divergence time from Oreochromines of 30.6–39.6 Myrs, showed lower rates of amplification (67%) and polymorphism (59%). The three other African cichlid tribes exhibited lower values for amplification and polymorphism rates: 38% and 50%, respectively, in the more derived lineage, Haplochromines, whereas a more heterogeneous pattern was found for the two more basal lineages, Chromidotilapiines (i.e., 47% and 20%, resp.) and Hemichromines (i.e., 19% and 50%, resp.). Allelic diversity varied with the same trends with a mean number of alleles per locus and species ranging from 3.7 and 3.3, respectively, for Oreochromis spp. and Sarotherodon spp. to 2.4 for Tilapia spp. and 1.6 in average (from 1.4 to 2.3) for the non-Tilapiines groups. The frequency of loci with putative null alleles also appeared to increase in the more distant species (supplementary material: Table S2). Rather than strictly reflecting reductions in polymorphism and/or the loss of the marker loci with increasing phylogenetic distance from the species in which the marker was cloned, these relationships are caused by mutations in the flanking regions complementary to the PCR primers. The conservation of microsatellites loci in the genomes has been shown to be potentially very long, and anyway much longer than the divergence time allowing successful cross-species amplification based on a given pair of primers, generally designed based on the only knowledge of the locus sequence in the species of cloning. The global success of cross-species amplification of a given microsatellite marker and/or the recovery of its different allelic variant (i.e., elimination of null allele) could then be enhanced in target species by either a specific optimisation of the amplification conditions or the modification of the sequence of the primers. This is especially appropriate when target species are distantly related to the cloning species of the markers and initial cross-species tests reveal low level of polymorphism with potentially high frequency of null allele (which would heavily bias any allele frequency-based estimates).

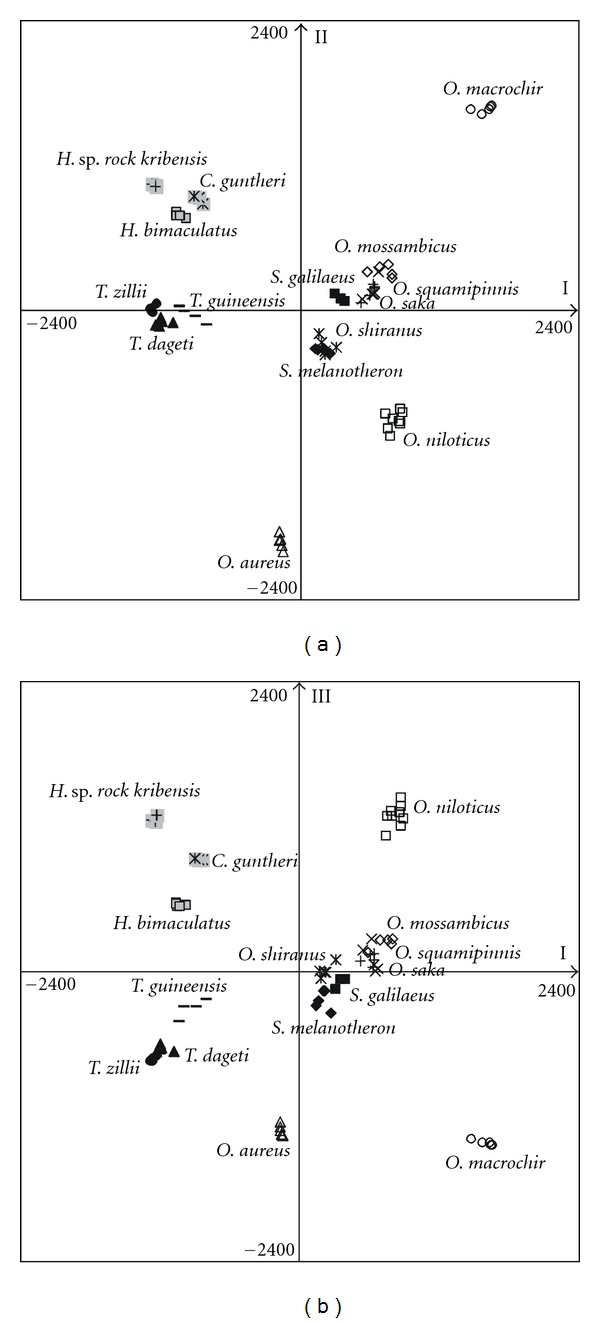

To represent the multi-locus pattern of genetic diversity across the 15 study species, we performed a population-based correspondence analysis using the software Genetix [46]. This multivariate analysis conducted on the genotype matrix allows to represent the clustering pattern among the different species groups, as well as among individuals within each of them in a factorial space (F1, F2, F3). This analysis allowed to clearly resolve the different species, except for O. saka and O. squamipinnis which are highly overlapping in the factorial space (Figure 1). Three separate groups of species were defined: the Oreochromines species, with all Oreochromis and Sarotherodon species, the Tilapia species, and all non-Tilapiines species. This clustering pattern reflects the phylogenetic relationships between the two tribes of Tilapiines sensu lato, that is, Oreochromines and Boreotilapiines. However the clustering of the three other tribes, which represent the most distant taxa from the source species, reveals the influence of the overall reduced polymorphism in highly distant taxa. This points out the limits of microsatellite size polymorphisms to estimate genetic divergence and/or phylogenetic relationship between too distantly related taxa, due to allele size homoplasy and/or increase of null allele frequency [19].

Figure 1.

Clustering of the 15 study species based on multilocus diversity: correspondence analysis based on the individual genotypes over the 29 microsatellites loci successfully amplified and performed on the barycentre of the species: (a) factorial plane F1-F2 and (b) factorial planes F1–F3.

4. Conclusion

This study provides a quantitative estimate of the transferability of O. niloticus-derived microsatellites markers across 5 divergent African cichlid tribes, from the highly studied Haplochromines group to less studied tribes as Oreochromines, Boreotilapiines, Chromidotilapiines, and Hemichromines. The high rate of cross-species amplification and polymorphism highlights the usefulness of microsatellites markers for comparative genetic studies within Oreochromines and other African cichlids tribes, including stock/species identification, comparative genome mapping, candidate genes, or hybridisation surveys. Despite the fast growing opportunities to produce large-scale genomic data in nonmodel organisms, we believe that highly polymorphic, locus-specific markers such as microsatellites will continue to be useful for a wide range of genetic analyses in African cichlids.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material provides the details about the efficiency of amplification for every locus by species combination, including also the corresponding level of polymorphism and allele size (Table S1). Furhtermore, the results of cross–specific amplification for each tested locus are provided for genus and tribes level (Table S2). Finally the frequency of shared alleles across species at genus and/or tribes level is provided.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stéphane Mauger and René Guyomard for laboratory assistance; Frederic Clota, Martial Derivaz, Philippe Morisens, and Jérome Lazard for their support in the scientific program of inter-generic hybridisation of tilapias, as well as the anonymous referee and the editor, Kristina M. Sefc, for their valuable comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the CIRAD and INRA (France).

References

- 1.Kocher TD. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5(4):288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornfield I, Smith PF. African cichlid fishes: model systems for evolutionary biology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 2000;31:163–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seehausen O. African cichlid fish: a model system in adaptive radiation research. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273(1597):1987–1998. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow GW. Cichlid Fishes: Nature’s Grand Experiment in Evolution. Cambridge, UK: Perseus Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann HA. Functional genomics of neural and behavioral plasticity. Journal of Neurobiology. 2003;54(1):272–282. doi: 10.1002/neu.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eknath AE, Hulata G. Use and exchange of genetic resources of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Reviews in Aquaculture. 2009;1(3-4):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josupeit H. World Market of Tilapia. Globefish Research Programme. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullin RSV. Cichlids in aquaculture. In: Keenleyside M, editor. Cichlid Fishes: Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1991. pp. 280–300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyl OLF, Ribbink AJ, Tweddlel D. Lake Malawi: fishes, fisheries, biodiversity, health and habitat. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management. 2010;13(3):241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witte F, van Densen WLT. Fish Stocks and Fisheries; A Handbook for Field Observations. Cardigan, UK: Samara House; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kocher TD. Status of genomic resources in tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). In: Proceedings of the Plant & Animal Genome Conference; January 2001; San Diego, Calif, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kocher TD. Genome sequence of a cichlid fish: the Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Proposal to the JGI Community Sequencing Program by he Cichlid Genome Consortium, 2005.

- 13.Lee WJ, Kocher TD. Microsatellite DNA markers for genetic mapping in Oreochromis niloticus . Journal of Fish Biology. 1996;49(1):169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocher TD, Lee WJ, Sobolewska H, Penman D, McAndrew B. A genetic linkage map of a cichlid fish, the tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Genetics. 1998;148(3):1225–1232. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estoup A, Angers B. Microsatellites and minisatellites for molecular ecology: theoretical and empirical considerations. In: Carvalho GR, editor. Advances in Molecular Ecology. IOS Press & Ohmsha; 1998. pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarne P, Lagoda PJL. Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1996;11(10):424–429. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeWoody JA, Avise JC. Microsatellite variation in marine, freshwater and anadromous fishes compared with other animals. Journal of Fish Biology. 2000;56(3):461–473. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rico C, Rico I, Hewitt G. 470 million years of conservation of microsatellite loci among fish species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1996;263(1370):549–557. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zardoya R, Vollmer DM, Craddock C, Streelman JT, Karl S, Meyer A. Evolutionary conservation of microsatellite flanking regions and their use in resolving the phylogeny of cichlid fishes (Pisces: Perciformes) Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1996;263(1376):1589–1598. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Primmer CR, Moller AP, Ellegren H. A wide-range survey of cross-species microsatellite amplification in birds. Molecular Ecology. 1996;5(3):365–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1996.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BY, Lee WJ, Streelman JT, et al. A second-generation genetic linkage map of tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) Genetics. 2005;170(1):237–244. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee BY, Hulata G, Kocher TD. Two unlinked loci controlling the sex of blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) Heredity. 2004;92(6):543–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee BY, Penman DJ, Kocher TD. Identification of a sex-determining region in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) using bulked segregant analysis. Animal Genetics. 2003;34(5):379–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2003.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streelman JT, Kocher TD. Microsatellite variation associated with prolactin expression and growth of salt-challenged tilapia. Physiological Genomics. 2002;2002(9):1–4. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00105.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellogg KA, Markert JA, Stauffer JR, Kocher TD. Microsatellite variation demonstrates multiple paternity in lekking cichlid fishes from Lake Malawi, Africa. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1995;260(1357):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Oppen MJH, Rico C, Deutsch JC, Turner GF, Hewitt GM. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in the cichlid fish Pseudotropheus zebra . Molecular Ecology. 1997;6(4):387–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1997.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L, Kaufman L, Fuerst PA. Isolation of microsatellite markers in Astatoreochromis alluaudi and their cross-species amplifications in other African cichlids. Molecular Ecology. 1999;8(5):895–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor MI, Meardon F, Turner G, Seehausen O, Mrosso HDJ, Rico C. Characterization of tetranucleotide microsatellite loci in a Lake Victorian, haplochromine cichlid fish: a Pundamilia pundamilia x Pundamilia nyererei hybrid. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2002;2(4):443–445. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albertson RC, Streelman JT, Kocher TD. Directional selection has shaped the oral jaws of Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(9):5252–5257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930235100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crispo E, Hagen C, Glenn T, Geneau G, Chapman LJ. Isolation and characterization of tetranucleotide microsatellite markers in a mouth-brooding haplochromine cichlid fish (Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor victoriae) from Uganda. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2007;7(6):1293–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda K, Takeshima H, Mizoiri S, Okada N, Nishida M, Tachida H. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in the cichlid fish in Lake Victoria, Haplochromis chilotes . Molecular Ecology Resources. 2008;8(2):428–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanetra M, Henning F, Fukamachi S, Meyer A. A microsatellite-based genetic linkage map of the cichlid fish, Astatotilapia burtoni (Teleostei): a comparison of genomic architectures among rapidly speciating cichlids. Genetics. 2009;182(1):387–397. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markert JA, Schelly RC, Stiassny ML. Genetic isolation and morphological divergence mediated by high-energy rapids in two cichlid genera from the lower Congo rapids. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010;10(1, article 149) doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann D, Stiassny MLJ, Schliewen UK. Two new sympatric Sarotherodon species (Pisces: Cichlidae) endemic to Lake Ejagham, Cameroon, west-central Africa, with comments on the Sarotherodon galilaeus species complex. Zootaxa. 2011;(2765):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stiassny MLJ, Schliewen UK. Congochromis, a new cichlid genus (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from Central Africa, with the description of a new species from the upper Congo River, democratic Republic of Congo. American Museum Novitates. 2007;(3576):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rognon X, Guyomard R. Large extent of mitochondrial DNA transfer from Oreochromis aureus to O. niloticus in West Africa. Molecular Ecology. 2003;12(2):435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pullin RSV. Ressources Génétiques en Tilapias pour L’aquaculture. Manila, Philippines: ICLARM; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trewavas E. Tilapiine Fishes of the Genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. London, UK: British Museum Natural History; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagl S, Tichy H, Mayer WE, Samonte IE, McAndrew BJ, Klein J. Classification and phylogenetic relationships of African tilapiine fishes inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2001;20(3):361–374. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klett V, Meyer A. What, if anything, is a Tilapia? Mitochondrial ND2 phylogeny of tilapiines and the evolution of parental care systems in the African cichlid fishes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2002;19(6):865–883. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarzer J, Misof B, Tautz D, Schliewen UK. The root of the East African cichlid radiations. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9(1, article 186) doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wohlfarth GW. The unexploited potential of tilapia hybrids in aquaculture. Aquaculture & Fisheries Management. 1994;25(8):781–788. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genner MJ, Seehausen O, Lunt DH, et al. Age of cichlids: new dates for ancient lake fish radiations. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(5):1269–1282. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marqueurs microsatellites: isolement à l'aide de sondes non-radioactives, caractérisation et mise au point. http://www.agroparistech.fr/svs/genere/microsat/microsat.htm.

- 45.Estoup A, Gharbi K, SanCristobal M, Chevalet C, Haffray P, Guyomard R. Parentage assignment using microsatellites in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) hatchery populations. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1998;55(3):715–725. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F. GENETIX 4.02, Logiciel Sous Windows pour la Génétique des Populations. Montpellier, France: Laboratoire Génome, Populations, Interactions, CNRS UMR 5000, Université de Montpellier II; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material provides the details about the efficiency of amplification for every locus by species combination, including also the corresponding level of polymorphism and allele size (Table S1). Furhtermore, the results of cross–specific amplification for each tested locus are provided for genus and tribes level (Table S2). Finally the frequency of shared alleles across species at genus and/or tribes level is provided.