Abstract

Purpose

Early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is potentially curable, however, many patients develop recurrent disease. Therefore, identification of biomarkers that can be used to predict patient’s risk of recurrence and survival is critical. Genetic polymorphisms or single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) of DNA- and histone-modifying genes, particularly those of O6-methylguanine DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT), have been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer as well as treatment outcomes in other tumors.

Experimental Design

We assessed the association of 165 SNPs in selected epigenetic enzyme genes, DNA methyltransferases, and methyl-CpG–binding proteins with cancer recurrence in 467 patients with stage I or II NSCLC treated with either surgery alone (N = 340) or surgery plus (neo)-adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 127).

Results

We found several SNPs to be strongly correlated with tumor recurrence. We identified 10 SNPs that correlated with the outcome in patients treated with surgery alone but not in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, which suggested that the addition of platinum-based chemotherapy could reverse the high genetic risk of recurrence. We also identified 10 SNPs that predicted the risk of recurrence in patients treated with surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy but not in patients treated with surgery alone. The cumulative effect of these SNPs significantly predicted outcomes with P-values of 10−9and 10−6, respectively.

Conclusions

The first set of genotypes may be used as novel predictive biomarkers to identify patients with stage I NSCLC, who could benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and the second set of SNPs might predict response to adjuvant chemotherapy.

Introduction

Approximately 60,000 people in the United States will be newly diagnosed with early-stage (stage I or II) non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in 2011. Surgery, most commonly lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection (MLD), supplemented with adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy for stage IB and II (1), offers a chance for cure with 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 60% to 80% in patients with stage I NSCLC and from 40% to 50% in patients with stage II NSCLC, respectively (2). Several research groups have recently used prognostic gene expression signatures and DNA promoter methylation assays to identify subsets of patients with early-stage NSCLC whose disease is likely to recur. However, most of these studies enrolled fewer than 100 subjects, were single institution studies, and/or often identified prognostic genes that did not overlap (3-7). To overcome the limitations inherent to these studies, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) supported the gene expression profiling of 442 early-stage lung adenocarcinomas to test prognostic gene expression models as part of the NCI Director’s Challenge Consortium for the Molecular Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Several gene expression models that correlated with patient outcomes were identified, and most of these models carried out better with the incorporation of clinical data (8).

Epigenetics refers to stable alteration in gene expression by DNA methylation and posttranslational modification of histones without modifying the underlying genetic sequence (9, 10). The modulation of chromatin-bound DNA via covalent DNA methylation or histone modifications is a fundamental mechanism regulating DNA accessibility for biologic processes such as gene transcription, DNA replication, and DNA damage repair and thereby plays a major role in embryogenesis, gene imprinting, and cancer development. Although cancer had been previously thought of as a disease with an exclusive genetic etiology, recent data have shown many epigenetic changes in tumor cells. Aberrant promoter DNA methylation, for example, is a common mechanism that cancer cells use to silence tumor suppressor genes. Also, epigenetic enzymes are commonly rearranged by translocations or deregulated by other means in leukemias and solid tumors (i.e., MLL translocations in acute leukemias and EZH2 amplifications and overexpression in prostate and breast cancer). In addition, genetic variations of O6-methylguanine DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) and the histone methyltransferase EZH2 have been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer (11, 12); furthermore, silencing of MGMT can predict responses of patients with glioblastoma to the chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide (13).

Because certain gene expression profiles might correlate with outcomes of patients with early-stage NSCLC and because epigenetics is an important mechanism of gene expression regulation, we hypothesized that genetic variations, or single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), in epigenetic genes may play an important prognostic role in patients with early-stage NSCLC. In the present study, we identified 2 classes of SNPs that were predictive of recurrence in patients with early-stage NSCLC. SNPs in the first class (N = 10) correlated with treatment outcome in patients with both lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma treated with surgery alone, but not in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Thus, adjuvant chemotherapy could reverse patients’ high genetic risk of recurrence, which is independent of histology, and these genotypes could be used to identify patients with stage IA or IB NSCLC who would benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. SNPs in the second class (N = 10) correlated with risk of recurrence in patients with lung adenocarcinoma treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy but not in patients treated with surgery alone, suggesting that these SNPs predict response to adjuvant chemotherapy. In summary, the findings of the present study suggest that specific genetic variations in DNA- and histone-modifying enzymes modulate clinical outcomes in patients with early-stage NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This prospective study included 467 patients with resectable stage I or II NSCLC who were enrolled in an epidemiologic lung cancer study at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) between 1995 and 2008. All patients underwent surgery with or without adjuvant chemotherapy, which was almost exclusively platinum based. Thirty-five patients received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, and 6 patients were treated with additional adjuvant radiation. All participants had completed a comprehensive epidemiologic questionnaire during an in-person interview that collected data on patients’ demographic characteristics, tobacco use history, prior medical history, and any history of cancer in first-degree relatives. All patients had donated a 40-mL blood sample for genotyping. The pertinent clinical information from all patients were collected by review of the medical records, in particular tumor size, clinical stage, pathologic stage, histologic type, tumor grade, treatment type, chemotherapy regimen, tumor recurrence, progression, time to recurrence or progression, and survival. The median follow-up time was 43.5 months. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by MD Anderson’s Institutional Review Board.

SNP selection and genotyping

One hundred and sixty-five haplotype-tagging SNPs and potential functional SNPs in 23 selected target genes (Supplementary Table S1), DNA methyltransferases, and methyl-CpG–binding proteins were identified using public SNP databases and the HapMap project (www.hapmap.org). The detailed procedure for compiling the panel of genes and SNPs were reported previously. Briefly, we identified the genes by extensively searching the Gene Ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org) and the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project (CGAP) GO Browser (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Genes/GOBrowser) databases. Tagging SNPs for each gene were selected using the ldSelect program (http://droog.gs.washington.edu/ldSelect.html) according to the following criteria: an r2 threshold of 0.8, a minor allele frequency greater than 0.01 (in the Caucasian population), and a location within 10 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site and 10 kb downstream of the transcriptional end site. Potentially, functional SNPs were located in coding (synonymous SNPs and nonsynonymous SNPs) and regulatory (promoter, splicing site, 5′ UTR, and 3′ UTR) regions. High-quality genomic DNAs from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 467 patients were obtained and all genotyping experiments were carried out according to the standard protocol provided by Illumina Inc. The genotyping results were generated with the Illumina’s BeadStudio software.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint event of this analysis was recurrence. Time to recurrence was computed from the date of diagnosis to date of first documented recurrence or to the date of last follow-up. Patients who were lost to follow-up, who died, or who were alive at the end of the study but had not developed recurrence were censored. The risk of recurrence for each SNP in patients treated with surgery only (A) and patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (B) were estimated as HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, while adjusting for sex, age, race, clinical stage, and smoking pack-year, where appropriate. As the genetic model underlying individual patients’ predisposition to cancer risk may follow dominant, recessive, or additive models, we considered all genetic models when we assessed the association of each SNP with recurrence. The model with the smallest P value was selected as the best-fitting model. We used the bootstrap resampling method to internally validate the SNPs that were significantly associated with recurrence. For each SNP, we generated bootstrap samples 100 times and estimated the HRs, 95% CI, and P values. The cumulative effects of favorable genotypes were assessed by combining individual SNPs that were found in the single SNP analysis to be significant predictors of recurrence to build genotype predictors. To validate the results of cumulative effects, we generated bootstrap samples 10,000 times. For each bootstrap run, data were drawn from the original data set with replacement and HRs were estimated using predefined grouping criteria. Bias-corrected CIs were calculated on the basis of the HRs from 10,000 bootstrap runs. Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests were used to assess differences in recurrence-free survival. The analysis was carried out using STATA software (version 10 STATA Corp.). To correct for multiple comparisons, q values implemented in R-package were computed for each SNP. All tests were 2-sided and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 467 patients with NSCLC enrolled in this study, 340 were treated with surgery only and 127 were treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1). Of the patients treated with surgery plus chemotherapy, 72% received adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 92 of 127) and 28% (N = 35 of 127) received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Two hundred and sixty-nine patients (89%) treated with surgery only and 98 patients (82%) treated with surgery and chemotherapy underwent lobectomy with or without MLD. We found no significant difference in pack-years of smoking (P = 0.138), smoking status (P = 0.800), race (P = 0.235), and histology (P = 0.643). The most frequent histologies were adenocarcinoma (63% of patients treated with surgery only and 58% of patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy) and squamous cell carcinoma (26% and 27%, respectively). However, the pathologic and clinical stages between the 2 groups were significantly different, which was not unexpected because of the widely accepted guidelines and standards for early-stage NSCLC treatment. Currently, the general recommendations are to provide adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II NSCLC but not patients with stage IA NSCLC. Whether adjuvant chemotherapy, which is a category IIB recommendation for high-risk patients, should be given to patients with stage IB NSCLC remains unclear. The majority of our patients were treated according to these principles with the following reasons for exceptions: contra-indications, strong patient preferences, and up- or downstaging of the patients’ diseases.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Treatment arm, N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Surgery only |

Surgery and chemotherapy |

P a |

| Patient number | 340 | 127 | |

| Age, median (range) |

67 (34–86) | 63 (29–83) | 0.006 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 166 (49) | 68 (54) | 0.364 |

| Female | 174 (51) | 59 (46) | |

| Pack-years, median (range) |

45 (0.2–256) | 40(0.1–159) | 0.138 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 48 (14) | 16(13) | 0.800 |

| Former | 168 (49) | 67 (53) | |

| Current and recent quitters |

124 (36) | 44 (35) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 305 (90) | 109 (86) | 0.235 |

| Black | 25 (7) | 10(8) | |

| Others | 10(3) | 8 (6) | |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 213 (63) | 74 (58) | 0.643 |

| Squamous cell | 87 (26) | 34 (27) | |

| NOS | 11 (3) | 7 (6) | |

| Other | 29 (9) | 12(9) | |

| Pathologic stage | |||

| Stage IA | 170 (50) | 21 (17) | 3.64×10−15 |

| Stage IB | 117 (34) | 49 (39) | |

| Stage IIA | 8(2) | 19(15) | |

| Stage IIB | 45 (13) | 38 (30) | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| Stage IA | 181 (53) | 23(18) | 1.58×10−12 |

| Stage IB | 113 (33) | 55 (43) | |

| Stage IIA | 10(3) | 14(11) | |

| Stage IIB | 36 (11) | 35 (28) | |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| ≤2 | 107 (31) | 26 (20) | 0.015 |

| 2~3 | 98 (29) | 32 (25) | |

| 3~5 | 84 (25) | 46 (36) | |

| <5 | 38 (11) | 21 (17) | |

| NA | 13(4) | 2 (2) | |

| Surgery | |||

| Wedge resection | 12(4) | 3 (3) | 0.043 |

| Lobectomy | 269 (89) | 98 (82) | |

| ± MLD | |||

| Bi-lobectomy | 7 (2) | 8 (7) | |

| ± MLD | |||

| Pneumonectomy | 15(5) | 11 (9) | |

| ± MLD | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Adjuvant | 0 (0) | 92 (72) | |

| Neoadjuvant | 0 (0) | 35 (28) | |

Abbreviation: MLD, mediastinal lymph node dissection.

P < 0.05 are in bold.

Associations between SNPs and recurrence risk

We identified 26 SNPs that significantly correlated with recurrence in patients treated with surgery only. Of these 26 SNPs, 10 SNPs conferred the risk of recurrence in opposing directions for the 2 treatment groups. Seven SNPs were associated with decreased risks of recurrence (HRs < 1) in patients treated with surgery only but with increased risk of recurrence (HRs > 1) in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy, and the other 3 SNPs, rs4792953, rs7359598, and rs12259379, conferred increased risks of recurrence (HRs >1) in patients treated with surgery only but had decreased risk of recurrence (HRs < 1) in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy (Table 2). One SNP, rs2072408 in CUL1, was also significantly associated with recurrence in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy (HR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.12–0.96 in patients treated with surgery vs. HR = 2.85, 95% CI = 1.06–7.67 in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy). These 10 SNPs were located in 5 genes and 5 genetic variations were in the MGMT gene. To internally validate the 10 SNPs, we carried out bootstrap resampling analysis and found that 6 SNPs had bootstrap P values of less than 0.05 at least 70 of 100 times.

Table 2.

Predictive SNPs for surgery alone and surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy

| Treatment arm surgery only |

Surgery and adjuvant–chemotherapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Gene | Location | Model | P a | HR (95% CI)a | P a | HR (95% CI)a |

| SNPs predictive for surgery only | |||||||

| rs2072408 | CUL1 | Intron | REC | 0.0424 | 0.35 (0.12–0.96) | 0.03855 | 2.85 (1.06–7.67) |

| rs10764896 | MGMT | Intron | ADD | 0.0071 | 0.61 (0.43–0.87) | 0.51737 | 1.15 (0.76–1.74) |

| rs4792953 | EZH1 | Intron | REC | 0.0177 | 1.99 (1.13–3.51) | 0.43748 | 0.70 (0.29–1.72) |

| rs140695 | MBD4 | Intron | DOM | 0.0181 | 0.53 (0.31–0.90) | 0.16216 | 1.64 (0.82–3.27) |

| rs11016879 | MGMT | Intron | ADD | 0.0188 | 0.62 (0.42–0.92) | 0.41988 | 1.21 (0.76–1.93) |

| rs7359598 | EZH1 | 5′UTR/promoter | REC | 0.0196 | 1.93 (1.11–3.35) | 0.75151 | 0.88 (0.40–1.92) |

| rs7068306 | MGMT | Intron | ADD | 0.0209 | 0.64 (0.43–0.93) | 0.66508 | 1.11 (0.70–1.75) |

| rs11016885 | MGMT | Intron | ADD | 0.0250 | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 0.21060 | 1.35 (0.84–2.15) |

| rs12259379 | MGMT | Intron | DOM | 0.0268 | 1.99 (1.08–3.67) | 0.22381 | 0.52 (0.18–1.49) |

| rs603097 | MBD2 | 5′UTR | DOM | 0.0287 | 0.53 (0.30–0.94) | 0.07299 | 1.89 (0.94–3.79) |

| SNPs predictive for surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| rs11016885 | MGMT | Intron | REC | 0.0481 | 0.34 (0.12–0.99) | 0.00791 | 2.99 (1.33–6.70) |

| rs2072408 | CUL1 | Intron | REC | 0.0424 | 0.35 (0.12–0.96) | 0.03855 | 2.85 (1.06–7.67) |

| rs4751115 | MGMT | Intron | REC | 0.5789 | 0.84 (0.46–1.55) | 0.00083 | 3.18 (1.61–6.27) |

| rs4751104 | MGMT | Intron | REC | 0.4120 | 0.70 (0.29–1.65) | 0.00382 | 3.29 (1.47–7.38) |

| rs11121832 | MTHFR | Intron | REC | 0.5187 | 0.68 (0.21–2.19) | 0.01026 | 3.37 (1.33–8.52) |

| rs1762429 | MGMT | Intron | DOM | 0.4557 | 0.82 (0.48–1.39) | 0.01201 | 3.14 (1.29–7.68) |

| rs12763287 | MGMT | Intron | DOM | 0.9881 | 1.00 (0.57–1.73) | 0.01493 | 2.39 (1.19–4.82) |

| rs11016798 | MGMT | Intergenic | ADD | 0.6979 | 0.93 (0.65–1.33) | 0.02285 | 1.82 (1.09–3.03) |

| rs1762438 | MGMT | 5′UTR | ADD | 0.7924 | 0.95 (0.68–1.35) | 0.02408 | 1.78 (1.08–2.93) |

| rs16828708 | MBD5 | 3′UTR | ADD | 0.7075 | 0.93 (0.64–1.36) | 0.03690 | 1.65 (1.03–2.65) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; REC, recessive; ADD, additive; DOM, dominant.

P and HR (95% CI) are in bold if P < 0.05.

Similarly, 10 SNPs in 4 genes were significantly associated with increased risk of recurrence (HRs > 1) in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy but had decreased risk of recurrence (HRs < 1) for patients treated with surgery alone. We also carried out bootstrap resampling analysis on these 10 SNPs as well and found that 3 SNPs had bootstrap P values of less than 0.05 at least 70 of 100 times. Fifteen other SNPs were significantly associated with recurrence in patients treated with the surgery and chemotherapy. However, we did not include these SNPs in the genetic predictor described below because their genetic risk of recurrence in patients treated with surgery only was in the same direction (i.e., both HRs < 1 in 2 treatment arms or both HRs > 1 in 2 treatment arms). Two of the SNPs, rs11016885 and rs2072408, were included in both sets of SNPs, but their risk of recurrence depended on the type of therapy. The association of the majority of SNPs remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons using a q value of 10%.

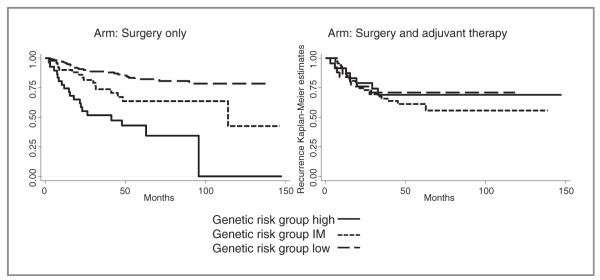

Cumulative effects of genotypes predictive for surgery only

We further assessed the cumulative effects of the favorable genotypes, which predict recurrence in patients treated with surgery only, but not in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients treated with surgery only and had 0 to 2 favorable SNP genotypes were defined as the high-risk group and had a recurrence risk of 51% (Table 3) with a median time to recurrence of 41.3 months (Fig. 1). Conversely, patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy and who had the same unfavorable or high-risk SNP combination had a lower recurrence risk of 29%. Among patients treated with surgery only, the intermediate-risk (3 favorable genotypes) and the low-risk groups (≥ 4 favorable genotypes) had 0.4-fold (95% CI = 0.2–0.78; P = 0.008) and 0.17-fold (95% CI = 0.09–0.32; P < 2.13 × 10 −8) decreased risk of recurrence compared with the high-risk group (0–2 favorable genotypes). The log-rank P value for this genotype predictor in patients treated with surgery only was 3.65 × 10−9 (Table 3). In contrast, the 3 SNP genotype risk groups did not correlate with recurrence in patients who were treated with surgery and chemotherapy (Log-rank P = 0.763). Patients in the low-risk genotype group treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy had a recurrence rate of 34% compared with 14% in patients treated with surgery only, which reflects differences in clinical stage. Patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy had higher numbers of patients for stage IB, IIA, and IIB (e.g., stage II: 39% in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy versus 14% in the surgery only group; Table 1). Biascorrected CIs, which were significant indicating that the results were not false-positive, were reported in Table 3. The association of the risk groups with recurrence exhibited similar effects in a stratified analysis of the 2 predominant histologic NSCLC subtypes, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (Table 3). Kaplan–Meier estimates for recurrence on the basis of the genetic predictor for surgery in patients treated with surgery only and patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy are displayed in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Combined genotype predictor based on prognostic SNPs for surgery only

| Genotype | No. of SNPs |

Rec, N (%) |

No Rec, N (%) |

HR (95% CI)a | P a | Log-rank Pa |

95% CI (bias-corrected)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm: surgery only | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 19 (51) | 18 (49) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 16 (25) | 47 (75) | 0.40 (0.20-0.78) | 0.008 | 0.19-0.86 | |

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 28 (14) | 167 (86) | 0.17 (0.09-0.32) | 2.13 × 10−8 | 3.65 × 10−9 | 0.09-0.35 |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 12 (26) | 35 (74) | 0.42 (0.17-1.00) | 0.050 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 17(15) | 100 (85) | 0.18 (0.08-0.41) | 5.15 × 10−5 | 3.44 × 10−5 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 4 (25) | 12 (75) | 0.18 (0.04-0.90) | 0.037 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 8(15) | 45 (85) | 0.09 (0.02-0.36) | 0.001 | 1.28 × 10−3 | |

| Treatment arm: surgery and adjuvant chernotherapy | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 7(29) | 17(71) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 7(27) | 19 (73) | 1.17 (0.39-3.49) | 0.780 | 0.29-5.37 | |

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 25 (34) | 48 (66) | 1.38 (0.58-3.28) | 0.461 | 0.763 | 0.51-4.64 |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 5 (33) | 10 (67) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 4(31) | 9 (69) | 0.98 (0.23-4.21) | 0.980 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 17 (39) | 27 (61) | 1.56 (0.50-4.83) | 0.439 | 0.800 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~2 | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 3 | 1 (11) | 8 (89) | 0.93 (0.04-19.25) | 0.960 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥4 | 5 (29) | 12(71) | 0.78 (0.09-6.48) | 0.816 | 0.663 | |

Abbreviations: Rec, recurrence; CI, confidence interval; IM, intermediate.

HR (95% CI), P, Log-rank P, and 95% CI (bias-corrected) are in bold if P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for recurrence based on the cumulative effect of favorable genotypes predictive for surgery only stratified by genetic risk groups (solid line, high-risk patients; dotted line, intermediate (IM)-risk patients; and dashed line, low-risk patients). Left, patients treated with surgery alone. Right, patients treated with surgery and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy.

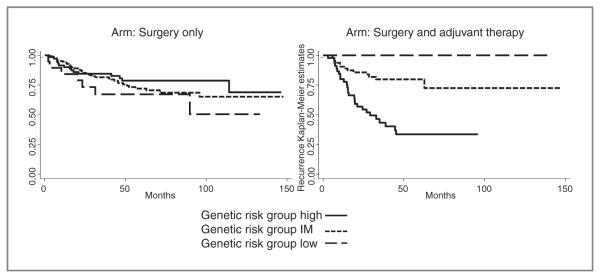

Combination of genotypes predictive of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy

Similar dose–response trends were observed among patients receiving surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 4 and Fig. 2). After applying the combined genotype predictor for adjuvant chemotherapy, patients, who had 0 to 6 favorable SNPs, were classified as high risk and had a recurrence rate of 59%. Using the high-risk group as a reference (0–6 favorable genotypes), patients in the intermediate-risk (7–9 favorable genotypes) had a 0.21-fold (95% CI = 0.1–0.44; P = 2.7 × 10−5) decreased risk of recurrence. No recurrences were observed in the 12 patients in the low-risk group (= 10 favorable genotypes). Biascorrected CIs indicated that the results were not false-positive. The log-rank P value for this genotype predictor for patients treated with surgery and adjuvant was 4.17 × 10−6. These 3 genotype risk-groups did not correlate with recurrence in patients who received surgery only (Log-rank P = 0.305). Similar associations were observed in the stratified analysis by histology, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (Table 4), however, the log-rank P value for squamous cell carcinoma did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.159) because of low patient numbers (N = 32).

Table 4.

Combined genotype predictor based on predictive SNPs for surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy

| Genotype | No. of SNPs |

Rec, N (%) |

No Rec, N (%) |

HR (95% CI)a | P a | Log-rank Pa |

95% CI (bias-corrected)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm: surgery only | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 15 (18) | 69 (82) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 41 (21) | 150 (79) | 1.44 (0.79-2.64) | 0.238 | 0.76-2.88 | |

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 7 (35) | 13 (65) | 2.50 (1.00-6.27) | 0.050 | 0.305 | 0.71-7.45 |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 10 (20) | 41 (80) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 25 (20) | 98 (80) | 1.38 (0.65-2.95) | 0.403 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 5.24 (1.43-19.16) | 0.012 | 0.262 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 3 (11) | 24 (89) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 12 (27) | 33 (73) | 2.38 (0.63-9.04) | 0.202 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 3.04 (0.50-18.49) | 0.228 | 0.226 | |

| Treatment arm: surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 27 (59) | 19 (41) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 13 (19) | 54 (81) | 0.21 (0.10-0.44) | 2.70 × 10−5 | 0.09-0.48 | |

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | N/A (N/A) | N/A | 4.17 × 10−6 | NA |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 19 (61) | 12 (39) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 8 (22) | 28 (78) | 0.21 (0.09-0.53) | 8.70 × 10−4 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 0 | 7 (100) | N/A (N/A) | N/A | 4.92 × 10−4 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||||

| Risk group high | 0~6 | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | 1 | |||

| Risk group IM | 7~9 | 4 (19) | 17 (81) | 0.3 (0.03-3.15) | 0.315 | ||

| Risk group low | ≥10 | 0 | 4 (100) | N/A (N/A) | N/A | 0.159 | |

Abbreviations: Rec, recurrence; CI, confidence interval; IM, intermediate.

HR (95% CI), P, Log-rank P, and 95% CI (bias-corrected) are in bold if P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for recurrence based on the cumulative effect of favorable genotypes predictive for surgery in combination with adjuvant chemotherapy stratified by genetic risk groups (solid line, high-risk patients; dotted line, intermediate (IM)-risk patients; and dashed line, low-risk patients). Left, patients treated with surgery alone. Right, patients treated with surgery and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy.

Discussion

Epigenetics, which is defined as regulation of transcriptional gene expression through DNA methylation and posttranslational histone modification, has been shown to play a critical role for cancer development. Examples are dysregulation of DNA damage repair, silencing of tumor suppressor genes by promoter methylation and translocation or overexpression of epigenetic enzyme genes (e.g., MLL) in many cancer cells. Furthermore, specific genetic variations in MGMT and EZH2 have been implicated in increased risk of developing lung cancer. In addition, silencing of MGMT has been well studied as a predictive biomarker for responses of patients with glioblastoma to the chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide. In this study, we determined whether genetic variations (165 haplotype tagging SNPs and potential functional SNPs) in 23 selected target genes, in particular DNA methyltransferases and methyl-CpG–binding proteins, were associated with recurrence in 467 patients with stage I or II NSCLC.

Significant associations were observed between several individual SNPs and clinical outcomes. We identified 26 SNPs that were associated with recurrence in patients received surgery alone and 25 SNPs that were correlated with recurrence in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Because our main goal was to identify predictive biomarkers in patients treated with either (i) surgery alone or (ii) surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, we focused on SNPs with opposing risk between the 2 treatment groups in further analyses. Ten SNPs were associated with recurrence in patients treated with surgery alone, but not in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In other words, patients treated with additional platinum-based chemotherapy had a dramatic reduction of their increased genetic recurrence risk than patients treated with surgery alone. For one of these SNPs, CUL1 rs2072408, the HRs for recurrence in patients treated with surgery alone (HR < 1) or surgery and chemotherapy (HR > 1) were even significant in opposite directions. Most of the SNPs we identified may not be functional, but might be surrogate markers for other underling genetic variations within that region of the genome—for example early metastasis genes—that are responsible for the increased cancer recurrence risk. Additional studies will be required to identify the causative SNP sequence variation and the mechanism(s) responsible for our observations. To enhance the prognostic power of the significant SNPs we combined them to build a genetic predictor for patients treated with surgery only. The P value of this the combined genotype predictor was highly significant at 3.65 × 10−9. Patients classified accordingly as having a high risk of recurrence had a 51% recurrence rate compared with 25% for the intermediate and 14% for the low-risk group. Interestingly, patients stratified by the genotype predictor for surgery alone who received adjuvant chemotherapy, had recurrence rates of only 27% to 34%, which were not significantly different. This finding in particular is remarkable because these patients had a higher clinical lung cancer stage of disease on average. Interestingly, the genetic risk groups predicted outcomes in both of the predominant histologic NSCLC subtypes, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In summary, our SNP genotype predictor might provide a new powerful tool to predict poor outcomes in patients with early-stage NSCLC, mostly patients with stage IA and IB, who would benefit from the addition of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. However, although our results were generated in 467 patients with early-stage NSCLC, they require further validation in additional patients.

Further analyses revealed 10 different genetic variations in DNA methyltransferases and methyl-CpG–binding proteins that were associated with risk of recurrence in patients with early-stage NSCLC treated with surgery and adjuvant (or neo-adjuvant) chemotherapy, but not surgery alone. Currently, most patients with stage IB and II NSCLC are treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (1), which engages several cellular pathways, including DNA damage/repair, cell-cycle control, and apoptosis pathways. To date, there have been no studies reporting involvement of epigenetic enzymes in platinum-based chemotherapy-related pathways in lung cancer, however, the MGMT methylation status has been linked to the outcome in patients with glioblastoma who received temozolomide treatment concomitant with and adjuvant to radiotherapy (13). The exact function of the significant SNPs is unclear because they are most likely tagging SNPs. The biologic mechanisms by which these genotypes determine their phenotypes and affect the outcome in patients with NSCLC who receive chemotherapy are also not clear. Future studies are needed to define their exact cellular mechanism of action. Regardless, we were able to build a genetic predictor of outcome in patients who received adjuvant and neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to surgery (P = 4.17 × 10−6). Patients in the high-risk group—that is, carrying six or fewer favorable genotypes—had a recurrence rate of 59% compared with 19% or 0% for the intermediate or low-risk group. Interestingly, this genotype predictor of recurrence in patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy did not predict recurrence in the control group of predominantly patients with stage IA treated with surgery alone. The identified genotype predictor for adjuvant chemotherapy was significant for patients with lung adenocarcinoma (P = 4.92 × 10−4), but not for squamous cell carcinoma (P = 0.159). However, this observation can be explained by the low number of patients with NSCLC in the squamous cell carcinoma group (N = 32). If validated as predictive biomarkers for chemotherapy, these results in combination with clinical data such as stage could become the basis for individualizing therapy. Genetic markers predictive of a good drug response could be used to identify patients for adjuvant chemotherapy and, in contrast, patients with a poor genetic signature, who are predicted to receive no benefits from adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy, may receive alternative means of adjuvant therapies such as radiation, different chemotherapy regimens, or even targeted agents.

In conclusion, we found highly significant associations between common genetic variants in epigenetic enzyme genes, DNA methyltransferases and methyl-CpG–binding proteins, and recurrence in patients with early-stage NSCLC. We were able to build 2 genotype predictors of outcome following (i) surgery alone and (ii) surgery with adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in a large population of 467 patients with NSCLC. The risk attributed to the unfavorable genotypes, which correlated with recurrence in patients treated with surgery alone, was reversed by adjuvant chemotherapy and these genotypes may therefore be used to select patients with stage I NSCLC for addition of adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, SNPs predictive of outcomes in patients treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy might be used to avoid unnecessary chemotherapy in resistant patients and guide other adjuvant treatment choices.

Translational Relevance.

The 5-year overall survival rates among patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with surgery only or surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy (for stage IB/II) range from 60% to 80% (stage I) to 40% to 50% (stage II). These treatment options offer a chance for a cure in many patients with early-stage NSCLC, yet 30% to 50% of patients develop recurrent disease. Therefore, one main research goal is to identify novel predictive biomarkers that can be used to identify patients with stage I NSCLC who are at a high risk of recurrent disease and who might benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Another goal is to predict responses of patients with NSCLC to anticancer therapies. Herein, we describe 2 novel genetic biomarkers that significantly predicted outcomes (P values of 10−9 and 10−6, respectively) on the basis of genetic variations in DNA-methyl-transferases and methyl-CpG–binding proteins in 467 patients with early-stage NSCLC treated with surgery alone or surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy.

Grant Support

This study was supported in part by National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P50 CA070907.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Pisters KM, Evans WK, Azzoli CG, Kris MG, Smith CA, Desch CE, et al. Cancer Care Ontario and American Society of Clinical Oncology adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant radiation therapy for stages I-IIIA resectable non small-cell lung cancer guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5506–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polednak AP. Trends in incidence rates of tobacco-related cancer, selected areas, SEER Program, United States, 1992–2004. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potti A, Mukherjee S, Petersen R, Dressman HK, Bild A, Koontz J, et al. A genomic strategy to refine prognosis in early-stage non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:570–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen HY, Yu SL, Chen CH, Chang GC, Chen CY, Yuan A, et al. A five-gene signature and clinical outcome in non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau SK, Boutros PC, Pintilie M, Blackhall FH, Zhu CQ, Strumpf D, et al. Three-gene prognostic classifier for early-stage non–small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5562–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, Han Y, Guo M, Ames S, et al. DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1118–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu CQ, Ding K, Strumpf D, Weir BA, Meyerson M, Pennell N, et al. Prognostic and predictive gene signature for adjuvant chemotherapy in resected non–small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4417–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schedden K, Taylor JMG, Enkemann SA, Jacobson JW, Beer DG. Gene expression–based survival prediction in lung adenocarcinoma: a multi-site, blinded validation study. Nat Med. 2008;14:822–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risch A, Plass C. Lung cancer epigenetics and genetics. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee HN, Verma M. Epigenetic mechanisms in cancer. Biomark Med. 2009;3:397–410. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Liu H, Zhang Z, Spitz MR, Wei Q. Association of genetic variants of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase with risk of lung cancer in non-Hispanic Whites. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2364–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon KA, Gil HJ, Han J, Park J, Lee JS. Genetic polymorphisms in the polycomb group gene EZH2 and the risk of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:10–6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c422d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, Sotti G, Frezza G, P Amistá, et al. Recurrence pattern after temozolomide concomitant with and adjuvant to radiotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma: correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1275–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]