Abstract

Aims: Protein phosphorylation is a principal signaling mechanism that mediates regulation of enzymatic activities, modulation of gene expression, and adaptation to environmental changes. Recent studies have shown a ubiquitous distribution of eukaryotic-type Serine/Threonine protein kinases in prokaryotic genomes, though the functions, substrates, and possible regulation of these enzymes remain largely unknown. In this study, we investigated whether cyanobacterial protein phosphorylation may be subject to redox regulation through modulation of the cysteine redox state, as has previously been reported for animals and plants. We also explored the role of a cyanobacterial Serine/Threonine kinase in oxidative stress tolerance. Results: The Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Serine/Threonine kinase SpkB was found to be inhibited by oxidation and reactivated by thioredoxin-catalyzed reduction. A Synechocystis mutant devoid of the SpkB kinase was unable to phosphorylate the glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit (GlyS), one of the most prominent phosphoproteins in the wild type, and recombinant purified SpkB could phosphorylate purified GlyS. In vivo characterization of the SpkB mutant showed a pronounced hypersensitivity to oxidative stress and displayed severe growth retardation or death in response to menadione, methyl viologen, and elevated light intensities. Innovation: This study points out a previously unrecognised complexity of prokaryotic regulatory pathways in adaptation to the environment and extends the roles of bacterial eukaryotic-like Serine/Threonine kinases to oxidative stress response. Conclusion: The SpkB kinase is required for survival of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under conditions implying increased concentrations of reactive oxygen species, and the activity of SpkB depends on the redox state of its cysteines. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 521–533.

Introduction

The convergence of redox signaling and phosphorylation-mediated signaling pathways through reversible cysteine oxidation in eukaryotic protein kinases and phosphatases has long been recognized (5, 43). In prokaryotes, however, such mechanisms that are involved in the regulation of kinase and phosphatase activities have not been reported so far.

Cyanobacteria perform oxygenic photosynthesis, which makes them unique among prokaryotes and sets the scene for complex redox biology (22). Cyanobacteria share a common ancestor with chloroplasts of photosynthetic eukaryotes and have a great impact on global photosynthetic productivity (6). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated during aerobic metabolism in most organisms, whereas cyanobacteria and plant chloroplasts should also suffer the consequences of additional ROS production that are associated with the photosynthetic electron transport (PET) and oxygen evolution (9, 22). Adverse environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, excess light, or nutrient starvation, lead to elevated ROS levels resulting from molecular oxygen acting as a sink for PET-derived reducing equivalents. The adaptation to such conditions is essential for survival and involves changes of gene expression and enzymatic activities in order to optimize photosynthesis and to avoid toxic ROS levels (9, 22). Therefore, the perception of ROS and subsequent signaling pathways in plants and cyanobacteria remains a topic of active investigation (22, 33).

Innovation.

Redox regulation of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation through the reversible cysteine oxidation of kinases and phosphatases is well established. In contrast, such convergence of redox signaling and phosphorylation signaling pathways has not been reported for prokaryotes and kinases, and phosphatases are absent from the prokaryotic disulphide proteomes reported to date. Here, we state that the cyanobacterial Serine/Threonine kinase SpkB is inactivated by oxidation and reactivated through reduction catalyzed by the thioredoxin TrxA. The extreme sensitivity of the SpkB null mutant to oxidative stress demonstrates that this Serine/Threonine kinase is involved in the antioxidant response of this cyanobacterium, thus extending the functions of bacterial eukaryotic-like Serine/Threonine kinases.

Bacterial signaling relies to a large extent on two-component systems involving histidine kinases and their corresponding response regulators and the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter referred to as Synechocystis) harbors 47 histidine kinases (2). DNA microarray experiments have shown that the expression of 32 of the 77 Synechocystis genes strongly induced by H2O2 depends on the histidine kinases Hik33, Hik34, Hik16, Hik41, or the peroxide-sensitive transcriptional regulator PerR (17). However, the ROS-inducible expression of 45 of the 77 genes is not governed by any known factor, which illustrates that there are ROS-inducible signaling pathways which are still to be discovered.

Until recently, phosphorylation in serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in cellular signaling has been mainly associated with eukaryotes (36). In animal cells, Ser/Thr kinases participate in redox signaling pathways and may also be directly regulated by redox modifications of critical cysteine residues. For example, a member of the mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, MEKK1, is reversibly inhibited by oxidative stress through S-glutathionylation (4). The reduction of oxidized cysteines is frequently catalyzed by thioredoxin, and this has also been observed for eukaryotic protein kinases. For example, the mammalian Ser/Thr protein kinase PKA (48) and the plant Ser/Thr protein kinase STN7 (3, 7, 39) are substrates for thioredoxin. However, the redox regulation of prokaryotic protein kinases has not been reported so far. Previously, we performed in-depth studies of the Synechocystis thioredoxin target proteome and found 77 proteins that interact with thioredoxin (25, 26, 30). Notably, most of these target proteins are metabolic enzymes, and no kinases or phosphatases are identified in these studies. Furthermore, kinases and phosphatases are conspicuously absent from the disulphide proteomes of other prokaryotic organisms reported to date (27 and references therein). This could mean that the thiol-based redox regulation of such enzymes does not occur in prokaryotes or, alternatively, that the kinases and phosphatases are not abundant enough to allow detection in proteomic screens.

Since the first discovery of a eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinase in the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus (35), progress in large-scale genomic sequencing projects has shown a ubiquitous distribution of such protein kinases in prokaryotes (19). Indeed, approximately two-thirds of all prokaryotes harbor eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases (37), indicating the widespread occurrence of signaling involving phosphorylation in serine and threonine residues also in these organisms. The Synechocystis genome encodes seven Ser/Thr protein kinases of the Pkn2-type, named SpkA through G (15, 49). However, SpkE lacks several key amino acids that are necessary for ATP binding and is not a true protein kinase (15). In addition, there are five putative kinases of the ABC1-type, named SpkH through L (50). The functions of a few cyanobacterial Ser/Thr kinases have been addressed through phenotypical characterization of the respective mutants. Thus, the knockout mutants for Synechocystis SpkA and SpkB were found to be deficient in phototactic motility (14, 16), a SpkD null mutant displayed impaired growth at low concentrations of inorganic carbon (23), and a knockout mutant for SpkG was hypersensitive to high salt concentrations (24). However, none of the substrates for any of these enzymes have hitherto been identified, and it remains unknown whether the cyanobacterial Ser/Thr kinases are subject to post-translational modification and regulation.

In this study, we have investigated the influence of the cysteine redox state on Synechocystis protein phosphorylation, given the role of reversible cysteine oxidation in the regulation of Ser/Thr protein kinases in eukaryotes. We also examined the possible roles of the Synechocystis Ser/Thr kinases in tolerance toward ROS. The results obtained extend the roles of Ser/Thr kinases in prokaryotes to include functions in oxidative stress response and affirm that the regulation of these enzymes may be as complex as that of eukaryotes.

Results

Synechocystis protein phosphorylation responds to the cysteine redox state

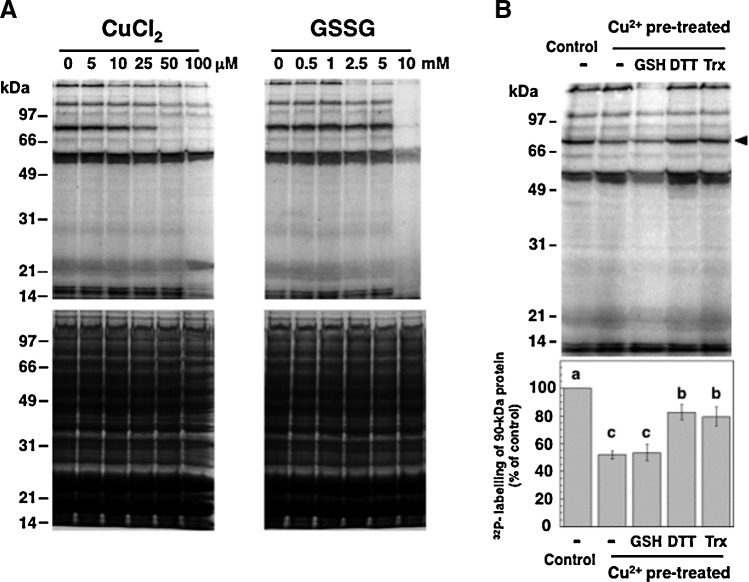

To monitor protein phosphorylation in Synechocystis and to search for a possible redox control of its kinase activities, soluble extracts of Synechocystis cells were pretreated with reagents affecting the cysteine redox state before the radioactive labeling of newly phosphorylated proteins. Initially, the effects of dithiothreitol (DTT), CuCl2, and hydrogen peroxide were tested (Fig. 1). DTT stimulated the phosphorylation of a 53-kDa protein, and hydrogen peroxide had a slight and generalized inhibitory effect. In contrast, CuCl2 strongly inhibited the phosphorylation of two proteins of 150 and 90 kDa (Fig. 1). The ability of Cu2+ to catalyze thiol oxidation, which is superior to that of Fe3+ and Ni2+, has been documented (11), and CuCl2 has been applied as a thiol oxidant in numerous studies on enzymatic redox regulation (13, 34). Oxidized glutathione (GSSG) has also been previously used to monitor the oxidative inactivation of protein kinases (41). Here, CuCl2 and GSSG displayed inhibitory effects on the phosphorylation of some of the heaviest labeled Synechocystis phosphoproteins (Fig. 2A, upper panels). However, GSSG was only efficient at very high concentrations. In order to investigate the nature and possible reversibility of the inhibition induced by Cu2+, samples were briefly pretreated with CuCl2, which was thereafter eliminated. Then, the samples were incubated with reduced glutathione (GSH), DTT, or purified Synechocystis thioredoxin TrxA, before the phosphorylation assay (Fig. 2B). TrxA is the most abundant of the four thioredoxins in Synechocystis and also the only thioredoxin that is essential for the survival of this organism (8). Quantification of the radioactive labeling of a 90-kDa protein showed that the pretreatment with CuCl2 led to about 50% inhibition of its phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Incubation with DTT or TrxA could restore phosphorylation to about 80% of the control level, whereas GSH did not relieve the inhibition (Fig. 2B).

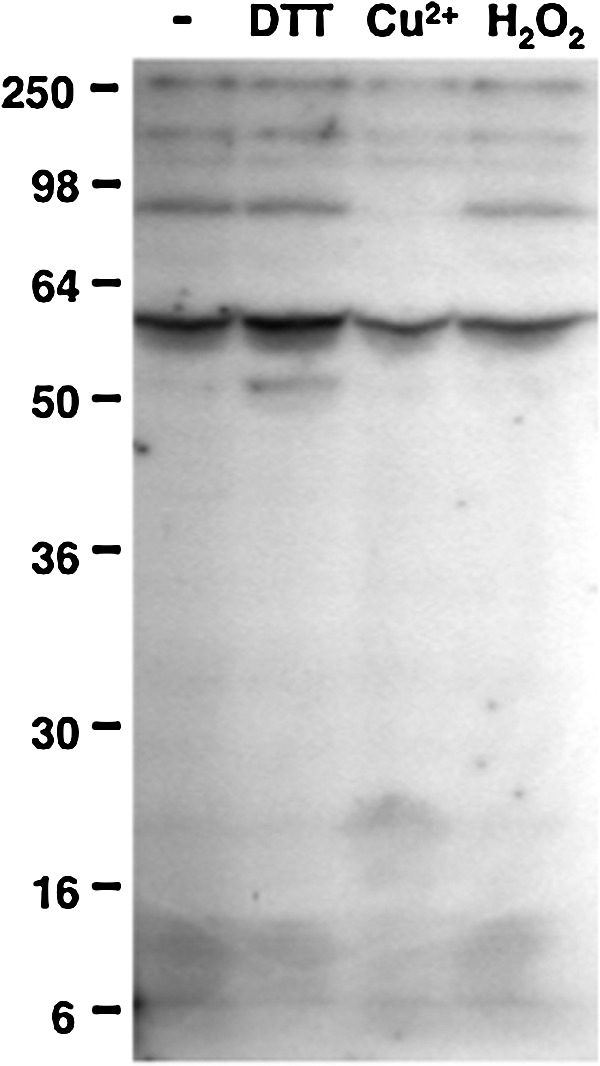

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of Synechocystis protein phosphorylation to redox reagents. Before radioactive labeling, 150-μg protein aliquots of the Synechocystis cytosolic fraction were treated for 20 min with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 μM CuCl2, or 0.1 mM H2O2. After the treatments, the phosphorylation assay was performed by incubating the samples with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP and 10 mM NaF. The proteins were resolved in 10% acrylamide gels, and the radioactively labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography. The first lane contains the untreated control sample.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition and reactivation of Synechocystis protein phosphorylation. (A) Inhibition of protein phosphorylation by thiol-oxidizing reagents. First, 150-μg protein aliquots of the Synechocystis cytosolic fraction were treated for 20 min with increasing concentrations of the thiol oxidants CuCl2 or oxidised glutathione (GSSG). The phosphorylation assay was thereafter performed by incubating the samples with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF. The proteins were resolved in 10% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie (lower panel), and the radioactively labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography (upper panel). (B) Reactivation of the phosphorylation of a 90-kDa protein by DTT and thioredoxin. Samples of Synechocystis cytosolic extracts were pretreated with 100 μM CuCl2 for 15 min, and control samples were incubated in parallel without additions. After the elimination of CuCl2 by successive ultrafiltration and dilution, aliquots containing 150 μg of protein were incubated for 15 min with either 5 mM reduced glutathione (GSH), 5 mM DTT, or 4 μM TrxA together with 0.2 mM DTT. After these treatments, the phosphorylation assay was performed as in (A). Proteins were resolved in 10% acrylamide gels and subjected to autoradiography (upper panel). The first lane contains a non-pretreated control sample, and the second lane contains a sample subjected to CuCl2-treatment without the posterior addition of reductants. The black arrowhead indicates a 90-kDa protein, the relative phosphorylation level of which was quantified and is displayed in the histogram (bottom panel). Bars represent the means of the level of radioactive labeling of this protein from three independent experiments. Standard error means are presented as error bars. Different letters (a, b, c) represent significantly different means with p-values of<0.05 according to the Student's t-test.

SpkB is a Ser/Thr kinase responsible for redox-sensitive protein phosphorylation

Aiming at identifying the kinase responsible for phosphorylation of the 90-kDa protein, we examined the phosphorylation patterns of a collection of Synechocystis mutants carrying insertions in the genes coding for the six Pkn2-family Ser/Thr kinases (Supplementary Fig. S1B, C; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/ars). Only the strain lacking the SpkB kinase (ΔSpkB) displayed a protein phosphorylation pattern different from that of the wild type (WT) under the conditions tested (Supplementary Fig. S2). A careful comparison showed that ΔSpkB was deficient in the phosphorylation of the 90-kDa protein and of two other proteins of 150 and 70 kDa, respectively (Fig. 3), whereas the phosphorylation of most other proteins was slightly altered with regard to the WT. Notably, the phosphorylation of the 150- and 70-kDa proteins, as well as that of the 90-kDa protein, was inhibited by Cu2+ and unaffected by DTT in the WT strain (Fig. 3). Moreover, the addition of DTT to the ΔSpkB samples did not lead to the recovery of phosphorylation of any of these proteins, while the residual phosphorylation of the 90-kDa protein in the ΔSpkB samples was still sensitive to Cu2+. These results would suggest that SpkB is responsible for most of the redox-sensitive phosphorylation of these proteins.

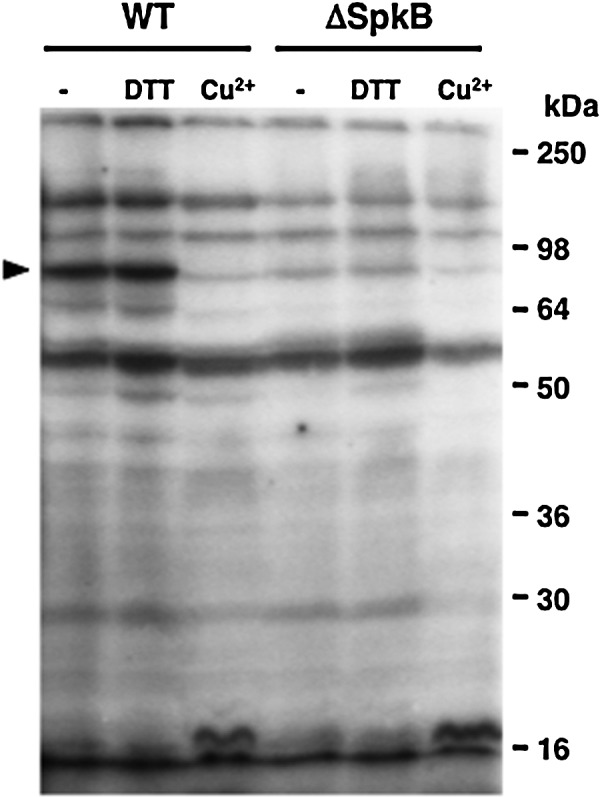

FIG. 3.

Patterns of protein phosphorylation in the Synechocystis wild type (WT) and the ΔSpkB mutant strain lacking the SpkB Ser/Thr kinase. The ΔSpkB mutant is unable to phosphorylate the 90-kDa protein. Samples of cytosolic extracts from each strain were treated for 15 min with 5 mM DTT, 100 μM CuCl2, or left untreated, and thereafter incubated with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF. Proteins were separated on 10% acrylamide gels, and radioactively labeled phosphoproteins were detected by autoradiography.

SpkB is inhibited by oxidation and reactivated by thioredoxin-catalyzed reduction

To examine whether the redox sensitivity of this phosphorylation involves modifications of the SpkB kinase, we decided to first clone and express Synechocystis SpkB in Escherichia coli. In an earlier study, the recombinant Synechocystis SpkB was found to be able to undergo autophosphorylation and also phosphorylate casein, myelin basic protein, and histone (14). However, no endogenous substrate or regulation of its activity was reported. In this study, we used casein to monitor the activity of SpkB expressed in E. coli (Fig. 4A). Extracts from E. coli cells transformed with an empty vector did not show casein kinase activity as compared with samples containing only casein without cellular extracts (Fig. 4A). However, the extracts from cells expressing SpkB displayed kinase activity towards casein and, in addition, several other proteins were heterologously phosphorylated by SpkB. The observed activity was substantially inhibited by the incubation of the cell extracts with CuCl2 before the assays (Fig. 4A), suggesting that SpkB might undergo inactivation as a result of thiol oxidation.

FIG. 4.

Activity of the recombinant Synechocystis SpkB kinase expressed in Escherichia coli. (A) The activity of SpkB is inhibited by CuCl2. Kinase activity of SpkB was analyzed in a phosphorylation assay using 2.5 μg of casein as an artificial substrate and 20 μg of E. coli soluble protein extracts from cells expressing (E) or not expressing (NE) the SpkB kinase. It should be noted that SpkB expression levels are too low to be visualized by Coomassie stain. A sample from cells expressing the kinase was treated for 15 min with 100 μM CuCl2. The phosphorylation assay was performed by incubating the samples with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF in order to label the phosphoproteins. The proteins were resolved in a 15% acrylamide gel, stained with Coomassie (lower panel), and the radioactively labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography (upper panel). Control samples containing only casein, untreated and treated with CuCl2, were also subjected to the phosphorylation assay and loaded in the two first lanes. (B) Oxidized SpkB is reactivated by thioredoxin. Histidine-tagged recombinant SpkB was enriched by nickel affinity chromatography. A sample of the SpkB preparation at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml was oxidized in the presence of 100 μM CuCl2 for 15 min, and Cu2+ was then removed by successive ultrafiltration and dilution. Aliquots containing 2 μg oxidized SpkB preparation were incubated with increasing concentrations of the thioredoxin TrxA using 0.2 mM DTT as an electron donor. The kinase activity was assayed by the addition of 2.5 μg of casein and incubating the samples with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP and 10 mM NaF. Proteins were resolved in 12% acrylamide gels, stained by Coomassie (lower panel), and the phosphorylation was detected by autoradiography (upper panel). The first lane contains a non-pretreated control sample, and the second lane contains a sample subjected to CuCl2-treatment without the subsequent addition of reductants. The black arrowhead indicates the position of SpkB, and the white arrowhead indicates TrxA.

In order to test whether thioredoxin could reactivate the oxidized kinase, we intended to purify the recombinant histidine-tagged SpkB. The predominant Coomassie-stained band, sometimes observed as a doublet, was confirmed by MALDI-TOF analysis to be identical to SpkB (Supplementary Table S1). The pretreatment with CuCl2 led to nearly a complete inhibition of SpkB kinase activity (Fig. 4B). Only a partial recovery of the activity was achieved by incubating the SpkB preparation with 0.2 mM DTT, whereas the addition of increasing concentrations of the thioredoxin TrxA significantly enhanced activation of the SpkB kinase (Fig. 4B). Thus, TrxA is able to catalyze the reactivation of oxidized SpkB.

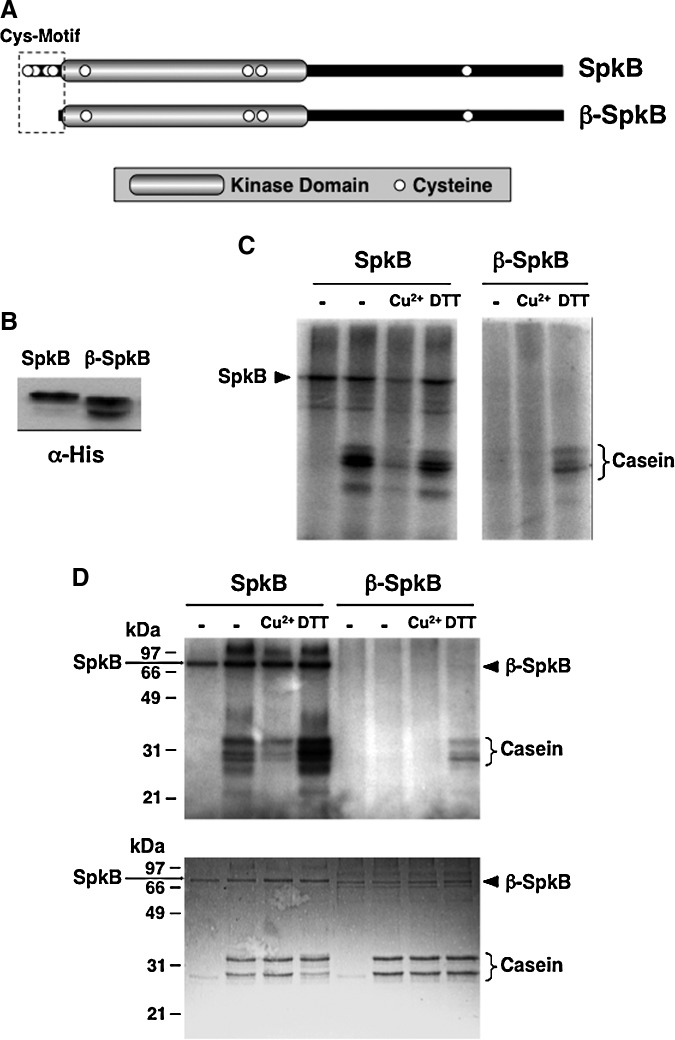

Deletion of the N-terminal Cys-motif of SpkB leads to requirement for exogenous thiols

Since thioredoxin mediates the activation of oxidized SpkB, at least one of its eight cysteines should be involved in such redox-dependent modulation of the kinase activity. The presence of a short N-terminal stretch containing two pairs of cysteines (Fig. 5A) has previously been observed for SpkB (14) and was denoted the “Cys-motif” (15). To investigate the potential role of this motif in the regulation of kinase activity, we constructed a truncated version of the enzyme, which was denoted β-SpkB (Fig. 5A). SpkB and β-SpkB were expressed in E. coli (Fig. 5B), and their activities were compared in cellular extracts using casein as a substrate (Fig. 5C). Unlike SpkB, β-SpkB displayed hardly any casein kinase activity in the absence of additions. However, the addition of DTT induced casein phosphorylation catalyzed by β-SpkB (Fig. 5C), showing that its catalytic activity remained intact. Similar results were obtained when comparing affinity-purified recombinant SpkB and β-SpkB (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Altered kinase activity of a truncated recombinant SpkB lacking the N-terminal cysteine-rich motif. (A) Schematic representation of SpkB and the truncated version, β-SpkB. The Synechocystis SpkB protein is 574 amino acids long. The constructed shorter version, β-SpkB, lacks the N-terminal cysteine-rich motif contained within the 24 first amino acids. The conserved kinase domain is shaded in gray, and the cysteines are indicated by open circles. (B) Western blot analysis of the recombinant SpkB and β-SpkB expressed as histidine-tagged proteins in E. coli. For a comparison of SpkB and β-SpkB kinase activities in crude E. coli cell extracts, a relative quantification of the expression levels of these kinase variants was performed using western blot with anti-histidine antibodies and subsequent quantification of the signals with the NIH image program. Here, soluble extracts from E. coli expressing SpkB and β-SpkB containing 20 and 40 μg of protein, respectively, were loaded on 10% acrylamide gels, and the anti-histidine antibodies (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) were used at a dilution of 1:1000. (C) A comparison of SpkB and β-SpkB kinase activities in crude extracts. Aliquots of soluble extracts from E. coli containing equal amounts of SpkB and β-SpkB according to the western blot analysis in (B), corresponding to 20 and 40 μg of protein, respectively, were assayed for kinase activities using 2.5 μg of casein as substrate. Before radioactive labeling, samples were treated with 100 μM CuCl2 (Cu2+) or 5 mM DTT, and untreated control samples (−) were incubated in parallel. Proteins were resolved in 12% acrylamide gels, and phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. The first lane contains a sample of SpkB without casein added. (D) A comparison of kinase activities of purified SpkB and β-SpkB. Assays were performed as in (C), except that 1 μg of recombinant SpkB and β-SpkB were used instead of crude extracts.

In order to explore the requirement for a reductant of β-SpkB, we performed titrations with increasing concentrations of DTT using extracts from cells expressing β-SpkB (Fig. 6A) and purified β-SpkB (Fig. 6B), respectively. Hence, we found that the addition of DTT at concentrations above 1 mM increased the casein phosphorylation more than 10-fold above the low basal level (graphs shown in Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). The addition of increasing concentrations of TrxA in the presence of 0.2 mM DTT (Fig. 6B, D) led to more than a 50-fold increase in casein phosphorylation as compared with the basal level (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). Hence, β-SpkB proved to be as active as the full-length enzyme provided that exogenous thiols, such as DTT or thioredoxin, are present in the assay.

FIG. 6.

Reduction enhances β-SpkB kinase activity. Aliquots of soluble extracts containing 20 μg of protein from E. coli expressing β-SpkB, (A) or aliquots of 2 μg purified β-SpkB, (B) were treated for 15 min with increasing concentrations of DTT up to 5 mM, or the thioredoxin TrxA up to 10 μM in the presence of 0.2 mM DTT. Kinase activities were tested using 2.5 μg casein as a substrate in an assay including 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF. The proteins were resolved in 12% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie (lower panels), and phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (upper panels). Nontreated control samples (−) were loaded in the first lanes of all gels. Quantification of the results are displayed in Supplementary Fig. S4.

The glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit GlyS is a substrate for SpkB

In order to facilitate identification of the prominent 90-kDa phosphoprotein, radioactively labeled samples from WT and ΔSpkB strains were subjected to isoelectric focusing/SDS-PAGE two-dimensional electrophoresis (Fig. 7). Autoradiographs (Fig. 7, right panels) clearly showed the intense labeling of the 90-kDa phosphoprotein in the WT, but not in ΔSpkB. This label corresponded to a protein spot visualized by Coomassie stain in both WT and ΔSpkB (Fig. 7, left panels). The identification by peptide mass fingerprinting revealed that the protein giving rise to this spot is the glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit GlyS (Supplementary Table S1).

FIG. 7.

The 90-kDa phosphoprotein is identical to the glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit (GlyS). Four-hundred μg of cytosolic proteins from the WT and ΔSpkB strains were resolved by two-dimensional IEF/SDS-PAGE after incubation with 0.5 mM ATP, 15 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF in order to label the proteins phosphorylated during this assay. The gels were stained with Coomassie (left panels), and the radioactively labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography (right panels). White arrowheads indicate the position of a protein identified as GlyS by means of MALDI-TOF analysis and peptide mass fingerprinting.

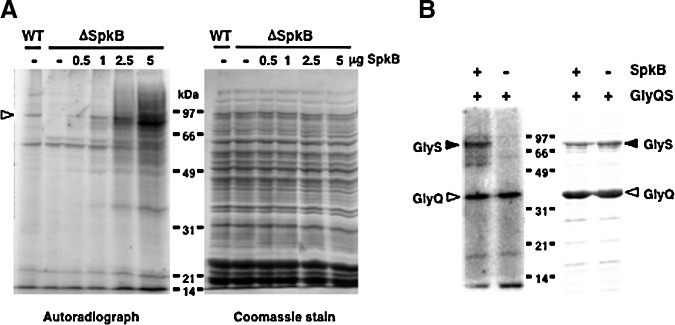

After establishing that GlyS does not become phosphorylated in the SpkB mutant strain, it remained to be determined whether SpkB could directly phosphorylate the GlyS protein. This issue was addressed using two different approaches. First, we added recombinant SpkB to cystosolic extracts from the ΔSpkB mutant (Fig. 8A). These experiments showed that the addition of 0.5 to 1 μg of recombinant SpkB to ΔSpkB samples resulted in the complete restoration of GlyS phosphorylation (Fig. 8A). Higher amounts of SpkB yielded the additional phosphorylation of a number of proteins previously undetected in our assays.

FIG. 8.

Activity of the recombinant Synechocystis SpkB kinase towards Synechocystis GlyS. (A) Complementation of the Synechocystis ΔSpkB mutant in vitro by the addition of recombinant SpkB. Protein phosphorylation was assayed in Synechocystis WT and ΔSpkB strains by incubating 150-μg protein aliquots of cytosolic extracts with 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 10 mM NaF. Increasing amounts up to 5 μg of recombinant SpkB were added to the ΔSpkB samples. Proteins were resolved in 12% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie (right panel), and the phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (left panel). The white arrowhead indicates the position of GlyS. (B) Phosphorylation of the glycyl-tRNA synthetase GlyS catalyzed by SpkB in vitro. Histidine-tagged GlyS and GlyQ subunits were co-expressed in E. coli and partially co-purified by nickel affinity chromatography. The phosphorylation assay contained 0.5 mM ATP, 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 10 mM NaF, and 10 μg of recombinant GlyQS in the presence and absence of 0.5 μg of purified SpkB. The samples were resolved in a 12% acrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie (right panel). The phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (left panel).

A heterotetrameric structure of glycyl-tRNA synthetases of the type α2β2 has been suggested to exist only in bacteria, and a dimeric structure of the type α2 can be observed mainly in eukaryotes (31). The α-subunit and parts of the β-subunit are required for aminoacylation of tRNA, and the α-chain contributes to amino acid- and ATP binding (10). Synechocystis possesses two genes that code for the α- (GlyQ) and β- (GlyS) subunits of glycyl-tRNA synthetase, respectively. Therefore, we decided to co-express histidine-tagged GlyS and GlyQ for purification. The phosphorylation assay based on radioactive labeling was performed using co-purified GlyS and GlyQ in the presence and absence of SpkB (Fig. 4B). The α-subunit of the glycyl-tRNA synthetase, GlyQ, was labeled in both the presence and absence of the kinase, probably as a result of its ATP-binding function. However, the β-subunit, GlyS, was labeled only in the presence of SpkB, thus confirming that it is able to undergo phosphorylation catalyzed by SpkB (Fig. 8B).

The SpkB null mutant is hypersensitive to oxidative stress

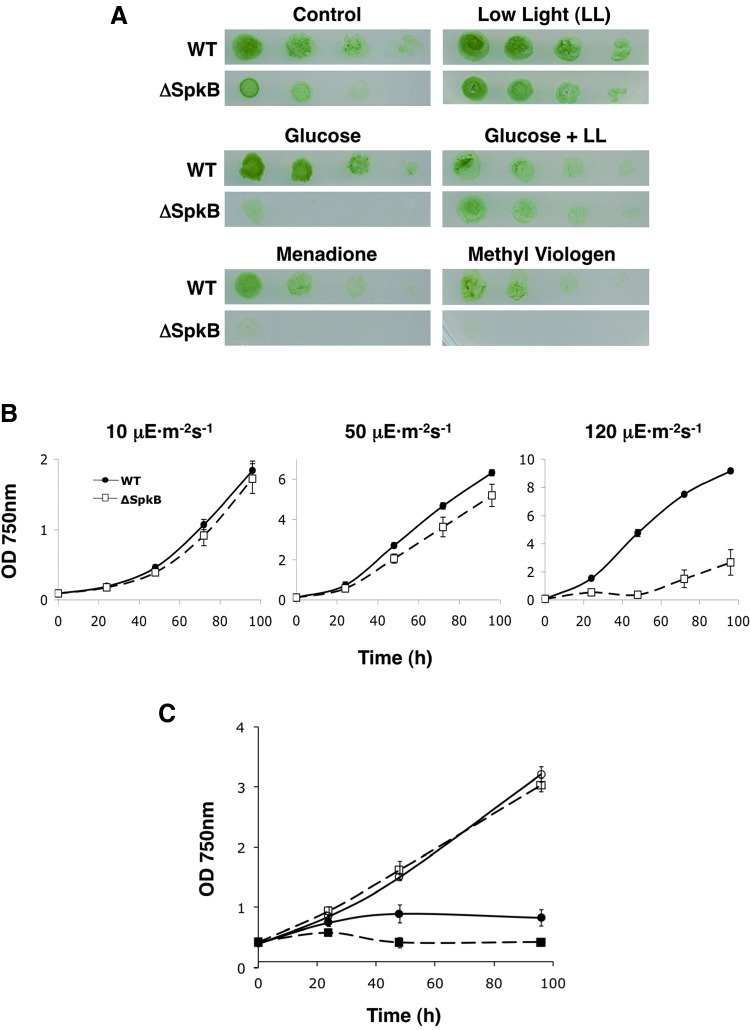

ΔSpkB grows slower on solid media than the WT Synechocystis strain under normal light conditions, whereas growth rates are comparable under low light conditions (Fig. 9A). The addition of 0.1 mM glucose exacerbated the ΔSpkB growth retardation under control light, while no effect of glucose was observed under low light (Fig. 9A). Given that strong illumination leads to high rates of PET and the concomitant production of ROS (see Ref. 9), these results suggest that ΔSpkB might be deficient in its response to oxidative stress. Furthermore, reducing equivalents derived from glucose enter the Synechocystis respiratory electron transport chain, which shares components with the PET chain (32), thus contributing to high overall electron transport rates. In order to analyze whether the observed effects could be the result of decreased oxidative stress tolerance, we examined the growth of ΔSpkB and WT strains on solid media, including menadione or methyl viologen. Menadione is a diquinone that stimulates the production of ROS (45). Methyl viologen enhances the production of superoxide anion radicals during oxygenic photosynthesis (18), which, in turn, leads to the formation of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals. Strikingly, both compounds completely abolished the growth of ΔSpkB (Fig. 9A), confirming the hypersensitivity of ΔSpkB to oxidative stress.

FIG. 9.

Hypersensitivity of the Synechocystis ΔSpkB mutant strain to oxidative stress conditions. (A) Serial dilutions of Synechocystis WT and ΔSpkB cultures were spotted on solid BG-11 agar plates and grown for 7 to 10 days. Under control conditions, the light intensity was 50 μE m−2 s−1, and low light (LL) implies a light intensity of 10 μE m−2 s−1. Menadione or methyl viologen was included at concentrations of 10 and 2 μM, respectively, in plates kept under control light conditions. Glucose at a concentration of 0.1 mM was included in plates kept under either control light or LL conditions. (B) Elevated light intensities inhibit the growth of ΔSpkB. Synechocystis WT and ΔSpkB strains were grown in liquid cultures at 10 μE m−2 s−1 light intensity to mid-logarithmic phase and were thereafter inoculated at an optical density (750 nm) of 0.1, bubbled with air containing 1% CO2, and illuminated at 10, 50, and 120 μE m−2 s−1 light intensity, respectively, for approximately 4 days. Optical densities at 750 nm were periodically measured to monitor growth The values in the growth curves represent the means from three independent experiments, and SDs are represented as error bars, which, on several occasions, are smaller than the symbols. WT, closed circles, and ΔSpkB, open squares. (C) Early growth arrest of ΔSpkB under iron deficiency. Synechocystis WT and ΔSpkB liquid cultures were grown in liquid cultures at 10 μE m−2 s−1 light intensity and were thereafter inoculated in E-flasks at an optical density (750 nm) of 0.4 either in a normal BG11 medium (open symbols) or in an iron-free medium lacking ferric ammonium citrate, the standard iron source, including 15 μM of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (closed symbols). The values in the growth curves represent the means from three independent experiments, and SDs are represented as error bars, which are occasionally smaller than the symbols. WT, circles, and ΔSpkB, squares. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

In liquid cultures grown at different light intensities (Fig. 9B), no significant difference was observed at a low light intensity, whereas at a normal light intensity, ΔSpkB grew slower than WT Synechocystis. A further elevation of the light intensity caused an initial 2-day growth arrest of ΔSpkB (Fig. 9B). Iron deficiency leads to the accumulation of ROS in plants (44) and cyanobacteria (20). The ΔSpkB mutant proved to be even more sensitive to iron starvation than the WT (Fig. 9C).

Finally, ROS levels were directly monitored through CM-H2DCF-DA fluorescence labeling after treatments of WT and ΔSpkB cultures with methyl viologen (Supplementary Fig. S5). Interestingly, low concentrations of methyl viologen result in enhanced ROS levels only in the mutant, whereas higher concentrations of methyl viologen lead to higher ROS levels only in the WT (Supplementary Fig. S5). A possible explanation would be that the higher concentrations of methyl viologen are toxic to the ΔSpkB mutant even during the brief treatments applied.

Discussion

The knowledge on redox-active cysteines in phosphorylation-mediated bacterial signaling is just beginning to emerge. Thus, it was recently reported that the Salmonella enterica response regulator SsrB, substrate for the histidine kinase SsrA, is regulated through the S-nitrosylation of a critical cysteine residue (12). In this study, we found that protein phosphorylation in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis is sensitive to changes in the cysteine redox state through the redox modulation of a eukaryotic-like protein kinase. However, GSSG is not efficient as an inhibitor of protein phosphorylation, and GSH is not capable of restoring the activity of oxidatively inactivated protein kinases in Synechocystis. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the glutathione system would play a role in the regulation of protein phosphorylation in this organism. In contrast, TrxA-catalyzed reduction completely restores the activity of the oxidized inactive SpkB kinase in vitro, which makes this Trx a plausible candidate as a physiological reductant of SpkB. The fact that GlyS phosphorylation in a freshly prepared WT cell extract is not stimulated by the addition of DTT indicates that SpkB is fully reduced in the cell under normal conditions. Considering that the residual phosphorylation of GlyS in the ΔSpkB mutant is still sensitive to Cu2+, redox-sensitive protein kinases that are unidentified as yet may also participate in this process. The truncated mutant β-SpkB, devoid of the N-terminal Cys-motif was found to be inactive unless exogenous thiols, such as DTT or TrxA, were present in the assay. This suggests that the Cys-motif, which includes the 4 first cysteines, functions as a redox buffer which maintains another critical cysteine in the kinase reduced. This other cysteine residue, or cysteine residues, should be essential for the activity of SpkB, as the complete activation of β-SpkB is achieved on reduction. Which of the other four cysteines is involved in this redox regulation is presently unknown; however, sequence alignments of SpkB with homologs from other cyanobacterial species reveal that the 5th and 6th cysteines are conserved, whereas the 7th and 8th cysteines are not (Supplementary Fig. S3).

SpkB shares its domain architecture with homologs from many other cyanobacterial species (49). The C-terminal half of the protein presents numerous pentapeptide repeats (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S6), which consist of several repetitions of a 5-amino-acid motif, usually A(D/N)LXX. The function of this domain in proteins is not clear, though a role in protein-protein interaction has been suggested (46). Eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases with putative redox regulatory N-terminal domains and potentially protein-binding C-terminal domains appear to be a recurrent theme among prokaryotes. Thus, a Ser/Thr protein kinase, pkn22, in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (21, 47), contains an N-terminal Cys-motif, a protein kinase domain, and a C-terminal β-helix repeat domain, a so-called PbH1 domain. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ser/Thr protein kinase PknG is a crucial virulence factor that is essential for survival within host macrophages (42). The crystal structure of PknG reveals an N-terminal rubredoxin-like domain, which contains two pairs of cysteines, the kinase domain and a C-terminal domain consisting of tetratricopeptide repeats (42). It remains to be explored whether these kinases might be redox regulated in a manner similar to Synechocystis SpkB. An encouraging observation is that a mutated version of PknG, with the cysteines of the rubredoxin domain exchanged for serines, is completely inactive (42). However, no attempts were made to reactivate this kinase and, thus, a redox regulation of PknG has not yet been confirmed.

A few phosphoproteins from cyanobacteria have been identified to date, and GlyS has not been previously reported as a cyanobacterial phosphoprotein. Nevertheless, an exhaustive analysis of the phosphoproteome of the gram-negative model bacterium E. coli led to the identification of 79 proteins phosphorylated on serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues and, notably, GlyS was one of the phosphoproteins identified in this study (28). The physiological role of GlyS phosphorylation in Synechocystis and other bacteria remains to be established. It should be kept in mind that some eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases exert functions other than the aminoacylation of tRNA, so-called “moonlighting,” and the phosphorylation-mediated release of these enzymes from multi-protein complexes has been suggested to favor their noncanonical functions (1, 38).

The Synechocystis SpkB null mutant showed drastically reduced oxidative stress tolerance. Therefore, we conclude that the most prominent role of SpkB is to promote the survival of this bacterium under conditions, such as elevated light intensities, which lead to enhanced ROS production. However, we also show that SpkB, paradoxically, is inactivated by cysteine oxidation, which would imply that SpkB might be inactive under the conditions of greatest necessity. The explanation probably lies in the SpkB Cys-motif, acting as redox buffer, and, if this would fail, an operative thioredoxin system that allows SpkB to withstand moderate oxidative stress (Fig. 10). Thus, in WT cells, SpkB would be active and functional, except under severe oxidative stress conditions leading to cell death.

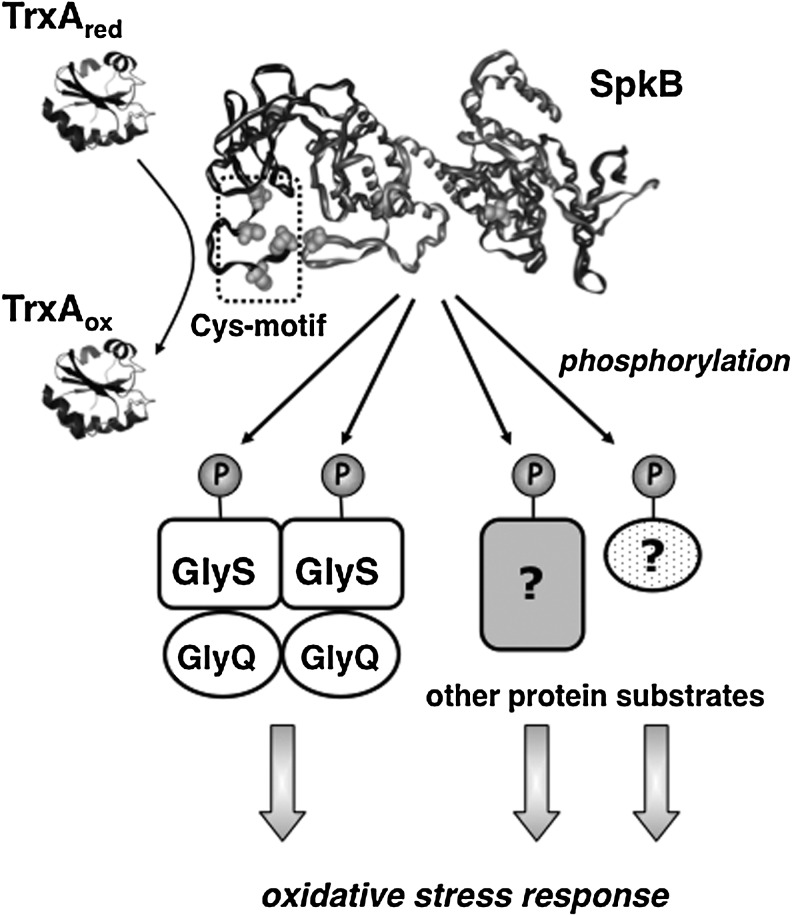

FIG. 10.

Scheme illustrating the role of SpkB in Synechocystis. The thioredoxin TrxA maintains the SpkB kinase reduced and active. (The respective modeled structures are used to represent these enzymes.) SpkB phosphorylates the glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit GlyS and other, as yet unidentified, protein substrates. The action of SpkB results in increased oxidative stress tolerance.

These studies show that the redox control of protein kinases is not unique to eukaryotes and raises the possibility that redox homeostasis might influence signaling through the modulation of protein phosphorylation also in other bacterial phyla.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The chemicals used in this study, such as DTT, GSH, GSSG, CuCl2, 2,2′-dipyridyl, menadione, and methyl viologen, were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri). The [γ-32P]ATP was from Perkin–Elmer (Walthman, Massachusets).

Cyanobacterial strains and growth conditions

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 cultures were photoautotrophically grown at 30°C under continuous illumination at an intensity of 50 μE m−2 s−1 (normal light), 10 μE m−2 s−1 (low light), or 120 μE m−2 s−1 (high light). The growth medium was BG11 (40) supplemented with 1 g/l NaHCO3 and bubbled with 1% (v/v) CO2 in air.

Cloning, expression, and purification

For the expression of proteins, the genes encoding SpkB (slr1697), GlyS (slr0220), and GlyQ (slr0638) were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using gene-specific oligonucleotides, which included NdeI and XhoI sites for cloning into the pET28 vector (SpkB, β-SpkB, and GlyS) and NdeI and HindII sites for pET22 (GlyQ). The sequences of these oligonucleotides were as follows: SpkB, forward (5′-CTGGTGAACCCATATGAGTTTTTGCG-3′) and reverse (5′-GCTTGGTTTGGTCAGAAACACTCGAGATT-3′); β-SpkB, forward (5′-GTGGGCATATGCTGCGCCTC-3′); GlyS, forward (5′-GCTCCCTTGCCATATGCCCCTGC-3′) and reverse (5′-GGAGGCCTCGAGGACATTTAAAAC-3′); GlyQ, forward (5′-CTTGTTGGCTTCATATGACCATTACTTTCC-3′) and reverse (5′-GTTTTTAAATCAAGCTTTACGAGGGAAA-3′). The proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3)-pLysS (Promega, Fitchburg, Wisconsin). The recombinant proteins were purified by nickel-affinity chromatography using the His-Bind resin (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany).

Assays for kinase activity

The cells were harvested and broken with glass beads in a buffer containing 25 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.6), 15% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM PMSF. Lysates were centrifuged at 16 000 g for 20 min. Protein concentrations of the cytosolic extracts were determined as described in (29). Cell extracts were incubated for 30 min at 25°C with a mixture composed of 0.5 mM ATP, 10 mM NaF, and 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. Kinase activities of recombinant SpkB and β-SpkB were assayed in vitro with [γ-32P]ATP by mixing 2 μg of purified kinase or 20 μg of E. coli extracts expressing SpkB or β-SpkB with 2.5 μg of casein or 10 μg of GlySQ as substrates. The radioactively labeled proteins were resolved in acrylamide protein gels, and the radioactivity was visualized using the Cyclone Plus Storage Phosphor System (Perkin-Elmer).

Two-dimensional electrophoresis

Protein samples were precipitated, washed by means of the commercial system 2-D Clean Up Kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), and resuspended in DeStreak Rehydratation Solution (GE Healthcare) supplemented with ampholytes with a pH range of 3–10 (BioRad, Hercules, California) at 0.5%, following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were separated in the first dimension using “DryStrips Immobiline Gel” (GE Healtcare) with a pH range of 4.7–5.9. The second dimension was performed using SDS-PAGE gels at 10% acrylamide concentration.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GlyS

glycyl-tRNA synthetase β-subunit

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PET

photosynthetic electron transport

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) through grants no. BFU2007-6300 and BFU2010-15708, co-funded to 70% by FEDER. A.M.-C. was the recipient of an FPU fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (MEC).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Arif A. Jia J. Moodt RA. Dicorleto PE. Fox PL. Phosphorylation of glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 dictates transcript-selective translational control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1415–1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashby MK. Houmard J. Cyanobacterial two-component proteins: structure, diversity, distribution and evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:472–509. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellafiore S. Barneche F. Peltier G. Rochaix J-D. State transitions and light adaptation require chloroplast thylakoid protein kinase STN7. Nature. 2005;433:892–895. doi: 10.1038/nature03286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross JV. Templeton DJ. Oxidative stress inhibits MEKK1 by site-specific glutathionylation in the ATP-binding domain. Biochem J. 2004;381:675–683. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross JV. Templeton DJ. Regulation of signal transduction through protein cysteine oxidation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1819–1827. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLong EF. Karl DM. Genomic perspectives in microbial oceanography. Nature. 2005;437:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nature04157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depege N. Bellafiore S. Rochaix J-D. Role of chloroplast protein kinase Stt7 in LHCII phosphorylation and state transition in Chlamydomonas. Science. 2003;299:1572–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.1081397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florencio FJ. Pérez-Pérez ME. López-Maury L. Mata-Cabana A. Lindahl M. The diversity and complexity of the cyanobacterial thioredoxin systems. Photosynth Res. 2006;89:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s11120-006-9093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foyer CH. Noctor G. Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: signaling, acclimation and practical implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:861–905. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freist W. Logan DT. Gauss DH. Glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1996;377:343–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen RE. Winther JR. An introduction to methods for analyzing thiols and disulphides: reactions, reagents and practical considerations. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain M. Jones-Carson J. Song M. McCollistere BD. Bourret TJ. Vázquez-Torres A. Redox sensor SsrB Cys203 enhances Salmonella fitness against nitric oxide generated in the host immune response to otral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14396–14401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005299107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikegami A. Yoshimura N. Motohashi K. Takahashi S. Romano PGN. Hisabori T. Takamiya K. Masuda T. The CHLI1 subunit of Arabidopsis thaliana magnesium chelatase is a target protein of the chloroplast thioredoxin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19282–19291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamei A. Yoshihara S. Yuasa T. Geng X. Ikeuchi M. Biochemical and functional characterization of a eukaryotic-type protein kinase, SpkB, in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Curr Microbiol. 2003;46:296–301. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamei A. Yuasa T. Geng X. Ikeuchi M. Biochemical examination of the potential eukaryotic-type protein kinase genes in the complete genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2002;9:71–78. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamei A. Yuasa T. Orikawa K. Geng X. Ikeuchi M. A eukaryotic-type protein kinase, SpkA, is reqired for normal motility of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1505–1510. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1505-1510.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanesaki Y. Yamamoto H. Paithoonrangsarid K. Shoumskaya M. Suzuki I. Hayashi H. Murata N. Histidine kinases play important roles in the perception and signal transduction of hydrogen peroxide in the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant J. 2007;49:313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger-Liszkay A. Kós PB. Hideg E. Superoxide anion radicals generated by methylviologen in photosystem I damage photosystem II. Physiol Plant. 2011;142:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupa A. Srinivasan N. Diversity in domain architectures of Ser/Thr kinases and their homologues in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latifi A. Jeanjean R. Lemeille S. Havaux M. Zhang C-C. Iron starvation leads to oxidative stress in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6596–6598. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6596-6598.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latifi A. Ruiz M. Jeanjean R. Zhang C-C. PrxQ-A, a member of the peroxiredoxin Q family, plays a major role in defense against oxidative stress in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latifi A. Ruiz M. Zhang C-C. Oxidative stress in cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:258–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurent S. Jang J. Janicki A. Zhang C-C. Bédu S. Inactivation of spkD, encoding a Ser/Thr kinase, affects the pool of the TCA cycle metabolites in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Microbiology. 2008;154:2161–2167. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang C. Zhang X. Chi X. Guan X. Li Y. Qin S. Shao H. Serine/threonine protein kinase SpkG is a candidate for high salt resistance in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindahl M. Florencio FJ. Thioredoxin-linked processes in cyanobacteria are as numerous as in chloroplasts, but targets are different. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16107–16112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534397100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl M. Kieselbach T. Disulphide proteomes and interactions with thioredoxin on the track towards understanding redox regulation in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. J Proteomics. 2009;72:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindahl M. Mata-Cabana A. Kieselbach T. The disulfide proteome and other reactive cysteine proteomes: Analysis and functional significance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2581–2642. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macek B. Gnad F. Soufi B. Kumar C. Olsen JV. Mijakivic I. Mann M. Phosphoproteome analysis of E. coli reveals evolutionary conservation of bacterial Ser/Thr/Tyr phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:299–307. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700311-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markwell MA. Haas SM. Bieber LL. Tolbert NE. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal Biochem. 1978;87:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mata-Cabana A. Florencio FJ. Lindahl M. Membrane proteins from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 interacting with thioredoxin. Proteomics. 2007;7:3953–3963. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazauric MH. Keith G. Logan D. Kreutzer R. Giegé R. Kern D. Glycyl-tRNA synthetase from Thermus thermophilus—wide structural divergence with other prokaryotic glycyl-tRNA synthetases and functional inter-relation with prokaryotic and eukaryotic glycylation systems. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:744–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mi H. Endo T. Schreiber U. Ogawa T. Asada K. NAD(P)H dehydrogenase-dependent cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803: a study of dark-starved cells and spheroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994;35:163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittler R. Vanderauwera S. Suzuki N. Miller G. Tognetti V. Vandepoele K. Gollery M. Shulaev V. Van Breusegem F. ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motohashi K. Kondoh A. Stumpp MT. Hisabori T. Comprehensive survey of proteins targeted by chloroplast thioredoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11224–11229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191282098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muñoz-Dorado J. Inouye S. Inouye M. A gene encoding a protein serine/threonine kinase is required for normal development of M. xanthus, a gram-negative bacterium. Cell. 1991;67:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pawson T. Scott JD. Protein phosphorylation in signalling–50 years and counting. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pérez J. Castañeda-García A. Jenke-Kodama H. Müller R. Muñoz-Dorado J. Eukaryotic-like protein kinases in the prokaryotes and the myxobacterial kinome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15950–15955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806851105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray PS. Arif A. Fox PL. Macromolecular complexes as depots for releasable regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rintamäki E. Martinsuo P. Pursihelmo S. Aro E-M. Cooperative regulation of light-harvesting complex II phosphorylation via the plastoquinol and ferredoxin-thioredoxin system in chloroplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11644–11649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180054297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rippka R. Deruelles J. Waterbury JB. Herman M. Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saze H. Ueno Y. Hisabori T. Hayashi H. Izui K. Thioredoxin-mediated reductive activation of a protein kinase for the regulatory phosphorylation of C4-form phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase from Maize. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scherr N. Honnappa S. Kunz G. Mueller P. Jayachandran R. Winkler F. Pieters J. Steinmetz MO. Structural basis for the specific inhibition of protein kinase G, a virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12151–12156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702842104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sen CK. Cellular thiols and redox-regulated signal transduction. Curr Top Cell Regul. 2000;36:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2137(01)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun B. Jing Y. Chen K. Song L. Chen F. Zhang L. Protective effect of nitric oxide on iron deficiency-induced oxidative stress in maize (Zea mays) J Plant Physiol. 2007;164:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thor H. Smith MT. Hartzell P. Bellomo G. Jewell SA. Orrenius S. The metabolism of menadione (2-methyl-1,4-naphtoquinone) by isolated hepatocytes. A study of the implications of oxidative stress in intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:12419–12425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vetting MW. Hegde SS. Fajardo JE. Fiser A. Roderick SL. Takiff HE. Blanchard JS. Pentapeptide repeat proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1–10. doi: 10.1021/bi052130w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu W-L. Jeanjean R. Liu Y-D. Zhang C-C. pkn22 (alr2502) encoding a putative Ser/Thr kinase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 is induced both by iron starvation and oxidative stress and regulates the expression of isiA. FEBS Lett. 2003;553:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zentella de Piña M. Vázquez-Meza H. Pardo JP. Rendón JL. Villalobos-Molina R. Riveros-Rosas H. Piña E. Signaling the signal, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase inhibition by insulin-formed H2O2 and reactivation by thioredoxin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12373–12386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X. Zhao F. Guan X. Yang Y. Liang C. Qin S. Genome-wide survey of putative Serine/Threonine protein kinases in cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zorina A. Stepanchenko N. Novikova GV. Sinetova M. Panichkin VB. Moshkov IE. Zinchenko VV. Shestakov SV. Suzuki I. Murata N. Los DA. Eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases SpkC/F/K are involved in phosphorylation of GroES in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis. DNA Res. 2011;18:137–151. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.