Abstract

Chronic inflammation is associated with promotion of malignancy and tumor progression. Many tumors enhance the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which contribute to tumor progression and growth by suppressing anti-tumor immune responses. Tumor-derived IL-1β secreted into the tumor microenvironment has been shown to induce the accumulation of MDSC possessing an enhanced capacity to suppress T cells. In this study, we found that the enhanced suppressive potential of IL-1β-induced MDSC was due to the activity of a novel subset of MDSC lacking Ly6C expression. This subset was present at low frequency in tumor-bearing mice in the absence of IL-1β-induced inflammation; however, under inflammatory conditions Ly6Cneg MDSC were predominant. Ly6Cneg MDSC impaired NK cell development and functions in vitro and in vivo. These results identify a novel IL-1β-induced subset of MDSC with unique functional properties. Ly6Cneg MDSC mediating NK cell suppression may thus represent useful targets for therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

Epidemiological studies emphasize the role of chronic inflammation in the promotion of various types of cancers (reviewed in [1]). The hallmarks of cancer-related inflammation include the presence at the tumor site of cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-23 [1–3]. IL-1β is a pleiotropic cytokine and induces the production by stromal and tumor-infiltrating cells of a cascade of molecules, including IL-6, prostaglandins and adhesion molecules that induce, sustain, and expand the inflammatory response (reviewed in [3, 4]). In the tumor microenvironment, IL-1β promotes angiogenesis [5, 6], tumor invasiveness (reviewed in [7]), carcinogenesis [8, 9], and affects immune function by many ways including indirectly through the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) [9, 10–12].

MDSC represent a heterogeneous population of myeloid cells defined in the mouse as Gr-1+CD11b+ cells encompassing granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic-like cells and early myeloid progenitors (reviewed in [13, 14]). The often-observed expansion of MDSC during tumor progression is dependent on the tumor itself [15] and tumor-derived factors (TDF) including IL-1β and S100A9/A8 (reviewed in [13, 14]). In agreement with this, IL-1β-secretion by modified tumor cells leads to the enhanced accumulation of splenic MDSC that potently suppress T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion [10–12, 16].

MDSC enhance tumor growth by several mechanisms including the suppression of the anti-tumor immune response. Mechanisms involving reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), L-arginine metabolism, nitrotyrosine (NT), secretion of IL-10, and sequestration of cystine/cysteine [14, 16, 17] are involved in mediating the suppression of T cells, while TGF-β1 is involved in the suppression of NK cells [18]. Notably, the expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by MDSC has been correlated with the level of tumor-secreted IL-1β [11].

Recent attention focused on the identification of tumor-associated MDSC subpopulations in different tumor models leading to the identification of a granulocytic polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocyte (PMN-MDSC) subset as Ly6GhighLy6C+SCChigh and a mononuclear subset characterized as Ly6G−Ly6ChighSCClow (Mon-MDSC [11, 19, 20]. Data from Bronte’s group suggest that the immunosuppressive potential of MDSC cell subsets is sensitive to tumor-derived cytokines such as GM-CSF [21]. Together, these studies underscore the heterogeneity within the MDSC-pool with regard to their phenotype and immunosuppressive capacities and that the composition of this pool appears to be dynamically regulated by the tumor microenvironment. NK cells play a major role in tumor immunosurveillance [22, 23]. The majority of NK cells are generated in the bone marrow and after maturation seed peripheral organs. In mice, mature NK cells are defined as CD3−NKp46+ cells expressing CD49b (DX5), CD122 (IL-2 receptor β), NKG2D and Ly49 molecules. CD27, CD11b and KLRG-1 expression divides peripheral NK cells into subsets and available data suggest that cells expressing only CD27+ to be less differentiated than CD27+CD11b+ NK cells, and cells expressing CD11b and KLRG1, but not CD27, may represent the most differentiated NK cells (reviewed in [24, 25]). Patients with diverse types of cancer (such as myelogenous leukemia and lung carcinoma) present with NK cell defects, including reduced NK cell numbers, reduced NK cell activity or reduced expression of activating receptors by NK cells [26, 27]. Although clinical studies and reports using mouse tumor models have described MDSC suppressing NK cell activities [18, 28, 29], the role of specific MDSC subsets on NK cell suppression remains unclear.

In this study, we identify a novel subset of MDSC induced by IL-1β, which lack Ly6C expression and demonstrate enhanced capacity to inhibit NK cell function in vitro and in vivo.

Results

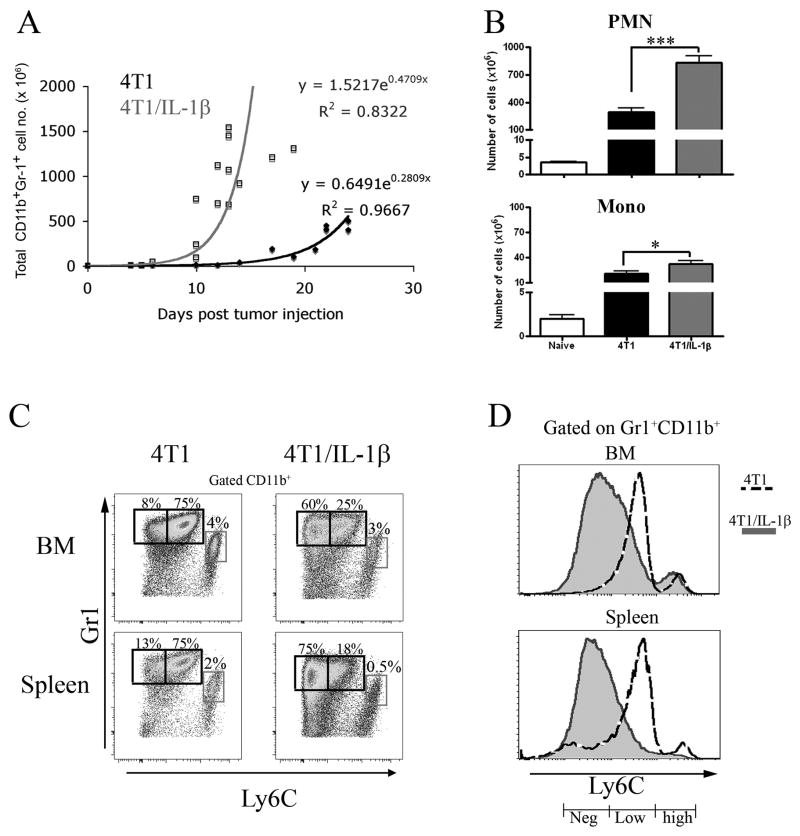

A novel PMN-MDSC subset lacking Ly6C expression

Inoculation of 4T1 or 4T1 cells over-expressing IL-1β (4T1/IL-1β, [11]) subcutaneously into BALB/c Rag2−/− mice resulted in significantly enlarged spleens in less than 7 days in both types of tumor bearing mice due to a strong expansion of MDSC (identified as CD11b+Gr-1+ cells) (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1). MDSC expansion was considerably faster in mice bearing 4T1/IL-1β tumors (Figure 1A), in line with previous results [11]. Regarding the distribution of polymorphonuclear (or granulocytic)-MDSC (PMN-MDSC; identified as Gr-1+CD11b+SSChigh cells) versus monocytic-MDSC (Mono-MDSC; identified as Gr-1+CD11b+SSClow cells) PMN-MDSC expansion was much greater than that of Mono-MDSC in both types of tumor-bearing mice. Thus when comparing mice with the same tumor diameter, this resulted in much higher numbers of PMN-MDSC in mice bearing established 4T1/IL-1β-tumors than in mice bearing established 4T1-tumors (Figure 1B; tumor diameter 10–12 mm). At the same time point Mono-MDSC numbers only increased marginally in the same mice (Figure 1B). The Matsushima laboratory has recently described PMN-MDSC as Ly6Clow, while Mono-MDSC were Ly6Chi [20]. Analysis of Ly6C versus Gr-1 expression on gated CD11b+ cells demonstrated that the population of PMN-MDSC (Gr-1high) in 4T1-tumor bearing mice was not homogeneous, but consisted of 80–90% Ly6Clow (Ly6Clow MDSC) and 10–20% of a previously undescribed population of MDSC lacking Ly6C expression (Ly6Cneg MDSC). Interestingly, in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice the ratio of Lyc6low to Ly6Cneg MDSC was reversed, that is, this newly identified subpopulation of Ly6Cneg MDSC represented 75–90% of polymophonuclear (PMN)-MDSC in those mice (Figure 1C, D and Supplemental Figure 2A). We observed the same pattern of Ly6C expression by Ly6G+ cells when we used antibodies of the clone 1A8 (anti-Ly6G) instead of clone RB6–8C5 (Ly6G/Ly6C) (data not shown). Flow cytometric analyses and Giemsa staining confirmed that Ly6Cneg MDSC were polymorphonuclear cells (Supplemental Figure 2B and C). We detected a similar predominance of Ly6Cneg MDSC in the tumor mass, blood, lymph nodes, thymus of 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, while Ly6Clow MDSC predominated in 4T1-tumor bearing mice at these sites (Supplemental Figure 2D)

Figure 1. 4T1/IL-1β tumors enhance the accumulation of splenic Ly6Cneg MDSC.

A) 2 × 105 4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells, respectively, were injected into the right footpad of BALB/c mice. Spleen cells from tumor-bearing mice (n=12–16) were counted and single cell suspensions were stained for FACS analysis. Total Gr-1+CD11b+ (black line - 4T1, grey line -4T1/IL-1β) cell numbers were calculated at the indicated days after tumor cell injection. Regression curves were calculated using MS Excel. CD11b+Gr-1+ cells were identified as indicated in Supplemental Figure 1. (B–D) Splenocytes from tumor-bearing BALB/c mice (tumor diameter: 10–12 mm) were stained for Gr-1, CD11b, Ly6C. (B) Total numbers of PMN-MDSC and Mono-MDSC present in the different tumor-bearing mice. (C) Gr-1 versus Ly6C expression on gated CD11b+ cells. CD11b+ cells were identified as indicated in Supplemental Figure 2A. (D) Histograms of Ly6C expression by Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from the indicated tumor bearing mice. (Shaded–4T1, dotted line - 4T1/IL-1β). The results show mean values pooled from 3–5 independent experiments (n=3–5 for each experiment). Error bars show SD. **p<0.01, *p<0.05, calculated using the two-sided Student’s t-test.

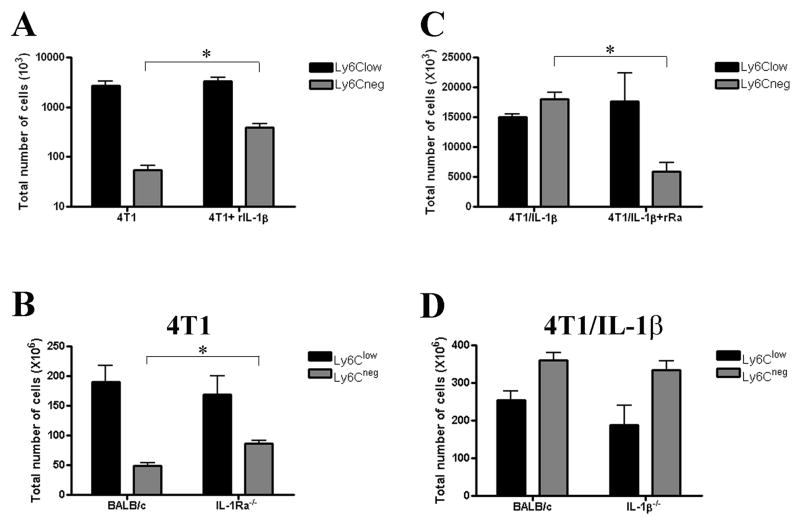

Ly6Cneg MDSC prevail under conditions of increased availability of IL-1β

Increasing the availability of IL-1β in 4T1-tumor bearing mice either via treatment with multiple doses of recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β; Figure 2A) or when recipient mice were deficient for IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra−/−; Figure 2B) resulted in significantly more Ly6Cneg MDSC, but not Ly6Clow MDSC. However, the absolute numbers of Ly6Cneg MDSC in these treated or mutant mice were lower than those detected in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice possibly because of different levels of available IL-1. In contrast, reducing the availability of IL-1β via treatment of 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice with recombinant IL-1Ra led to a decreased number of Ly6Cneg MDSC and delayed tumor growth compared to untreated mice (Figure 2C and data not shown). Together these data supported the importance of IL-1β in the expansion of Ly6Cneg MDSC. Furthermore, inoculation of 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells into wild-type or IL-1β−/− mice resulted in similar numbers of Ly6Cneg MDSC in both types of mice (Figure 2D), suggesting that tumor-derived IL-1β could substitute for the absence of host IL-1β.

Figure 2. Tumor and host derived IL-1β regulates size of splenic Ly6Cneg MDSC pool.

Cells were identified as indicated in Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 2A. (A) The total numbers of PMN-MDSC isolated from BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 (tumor diameter: 7 mm) treated with or without rIL-1β. (B) The total numbers of PMN-MDSC isolated from BALB/c and IL-1Ra−/− mice bearing 4T1. (C) The total numbers of PMN-MDSC isolated from BALB/c mice bearing 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells (tumor diameter: 7 mm) treated with or without rIL-1Ra. (D) The total numbers of PMN-MDSC isolated from BALB/c and IL-1β−/− mice bearing 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells. Error bars show SD. *p<0.05, calculated two-sided Student’s t-test.

Ly6Cneg MDSC potently suppress T cells

The discovery of a novel subpopulation of MDSC prevailing in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice may explain the reported phenotypic differences of MDSC from these mice compared to those from 4T1-tumor bearing mice [11]. It has been reported that splenic MDSC derived from 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice expressed more reactive oxygen species (ROS) and were more effective T cell suppressors [11]. We hypothesized that these differences may be attributable to the presence (and predominance) of the Ly6Cneg MDSC subset. Indeed, we found that Ly6Cneg MDSC expressed higher levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS2) and ROS than Ly6Clow MDSC (Supplemental Figure 3A). In line with these observations, we observed that Ly6Cneg MDSC on a per cell basis were significantly more potent, inhibitors of the proliferation of antigen-activated T cells than Ly6Clow MDSC (Supplemental Figure 3B).

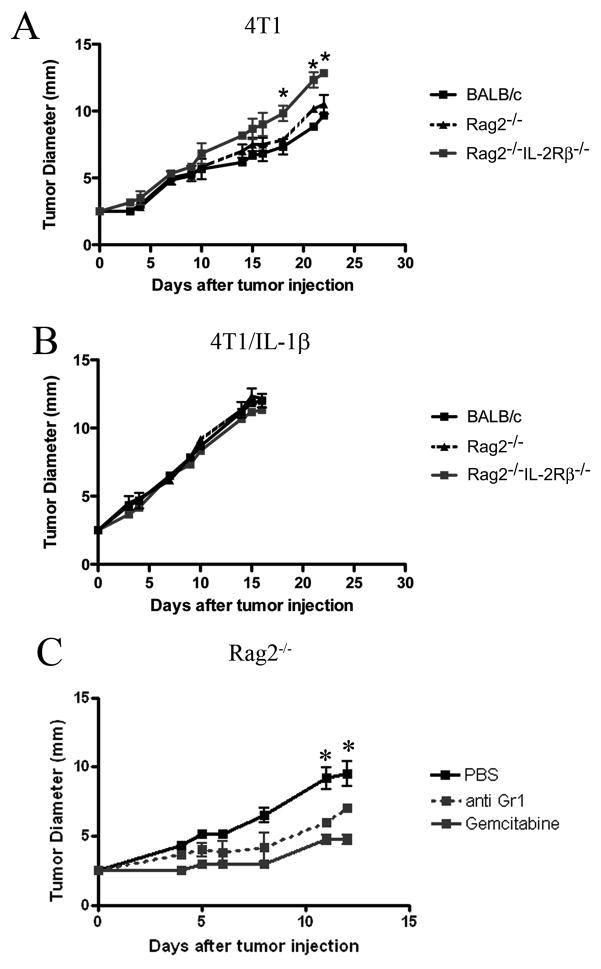

4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β-tumors differentially affect innate immunosurveillance

To study the ability of Ly6Cneg MDSC versus Ly6Clow MDSC to inhibit innate immunosurveillance, we assessed the capacity of 4T1/IL-1β versus 4T1 cells to form solid tumors upon injection into the footpad of BALB/c, BALB/c Rag2−/− (T and B cell-deficient), and BALB/c Rag2−/−IL-2Rβ −/− mice (lacking NK cells in addition to T and B cells). While 4T1 cells induced local tumor growth in all mice (Figure 3A) the kinetics of tumor growth varied in the different recipients. Notably, in BALB/c Rag2−/−IL-2Rβ−/− mice tumor development was significantly faster than in BALB/c Rag2−/− mice (Figure 3A), indicating the involvement of NK cells in the delayed tumor growth in the latter. In contrast, there was no difference in the kinetics of tumor growth upon inoculation of 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells in the various recipients, however, the IL-1β secreting tumors grew consistently faster than 4T1 tumors in NK-proficient BALB/c Rag2−/− mice (Figure 3B). Depletion of MDSC using either anti-Gr-1 monoclonal antibodies or Gemcitabine (GEMZAR, [30]) resulted in a significant delay of tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice transplanted with 4T1/IL-1β cells (Figure 3C and data not shown; p<0.05).

Figure 3. Enhanced tumorigenicity of IL-1β-secreting 4T1 tumors.

Tumor diameters at the indicated time points after injection of 2×105 (A) 4T1 and (B) 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells into the footpad of BALB/c, Rag2−/− and Rag−/−IL-2Rβ−/− mice (n=3–4). (C) 4T1/IL-1β tumor cells were injected into the footpad of Rag2−/− mice (n=4); MDSC were eliminated by Gemcitabine treatment or depleted with antibodies against Gr-1. Tumor diameters were measured every 2–3 days. One representative experiment from 2–3 preformed is shown. Error bars show SD. *p<0.05, calculated two-sided Student’s t-test.

Together, these data suggested the involvement of NK cells in the host anti-tumor response and that Gr-1+ cells were involved in the inhibition of the Rag2-independent anti-tumor activity in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor-bearing mice.

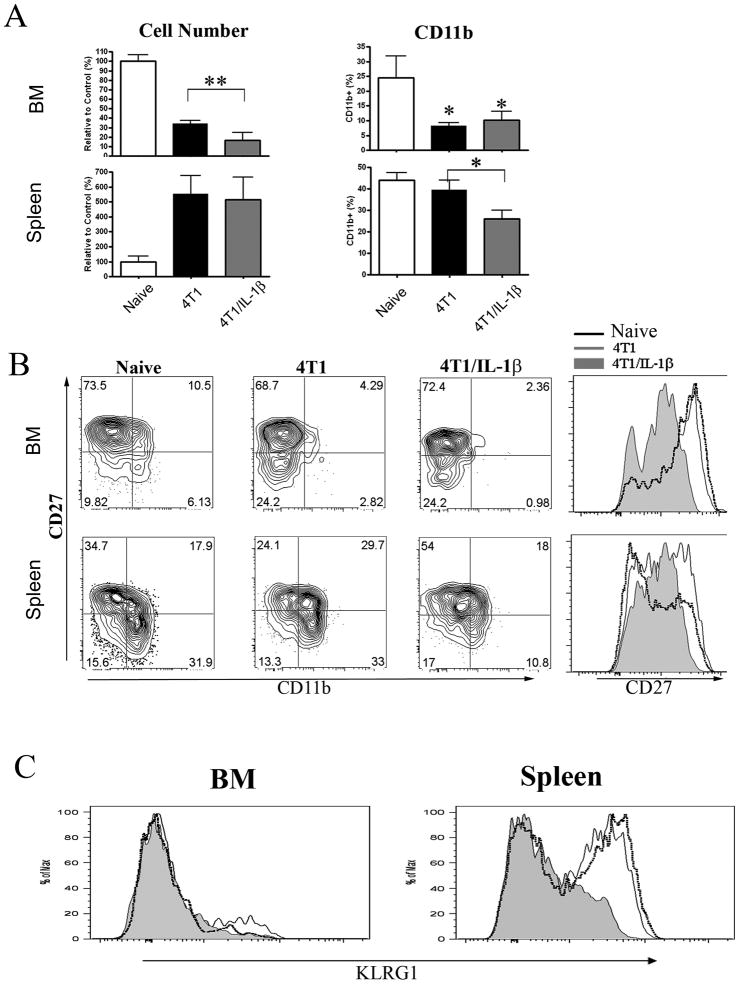

4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β-tumors differentially affect host NK cells

We analyzed the NK cell compartment in mice bearing established tumors and detected a reduced number (p<0.05) of CD122+NKp46+ NK cells in the bone marrow of 4T1-(30% of control cell numbers) and 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice (15% of control cell numbers) (Figure 4A, left, and Supplemental Figure 4). We then analysed the development of NK cells in the different mice. CD27 is a marker of immature NK cells, while sequential up-regulation of CD11b and KLRG-1 expression is associated with NK cell maturation [25]. Using these markers we found a similar percentage of CD27+ NK cells in the bone marrow of all mice (Figure 4B), however, NK cells from 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice expressed 5–10-times less CD27 protein than NK cells from the other mice (Figure 4B). Moreover, the tumor bearing mice contained less CD11b+ NK cells in the bone marrow (Figure 4A (right) and B) indicating a block in the differentiation of NK cells in these mice.

Figure 4. Impaired NK cell development in 4T1/IL-1β tumor bearing mice.

Cells of BM (top) and spleen (bottom) from naïve Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− mice bearing 4T1 or 4T1/IL-1β tumors. NK cells were identified as shown in Supplemental Figure 4. (A) Left, Comparison of CD122+ NKP46+ NK cell numbers from the indicated tumor bearing mice to naïve controls (controls were set to 100%). Right, percentage of CD11b+ cells among CD122+NKp46+ cells. (B) Contour plot of CD27 versus CD11b expression and histogram of CD27 expression on NK cells. (C) Histogram of KLRG1 expression on BM ‘left) and splenic(right) CD122+NKp46+ NK cells. All data are derived from 6–8 mice bearing tumors of 9–11mm diameter in 3 independent experiments. Error bars show SD. **p<0.01, *p<0.05 using two-sided Student’s t-test.

In contrast to the BM, the total number of splenic NK cells was 5-fold increased in both groups of tumor bearing mice (Figure 4A). More importantly, CD11b+ and KLRG-1+ cells were absent from 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, while splenic NK cells from 4T1-tumor bearing mice expressed CD11b and KLRG1 at levels and frequencies comparable to naïve mice (Figure 4 B and C).

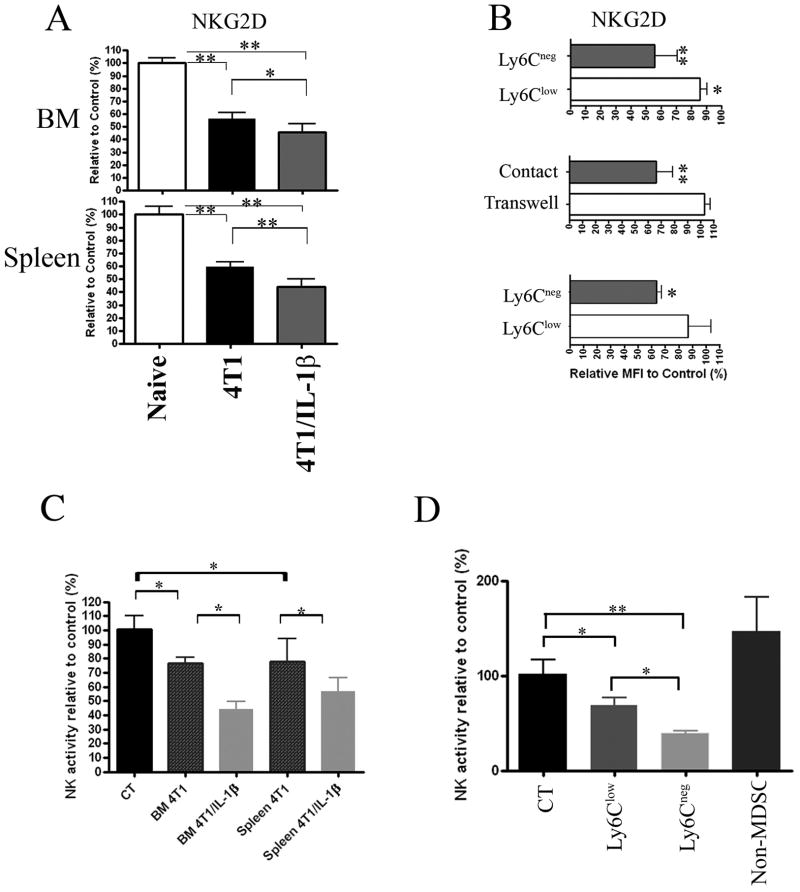

Ly6Cneg MDSC affect NKG2D expression by NK cells in vitro and in vivo

Further analyses showed a rapid down-modulation of NKG2D but not NKp46 expression by NK cells after injection of 4T1- and 4T1/IL-1β-tumor cells. The reduced expression of NKG2D occurred earlier and was more pronounced in 4T1/IL-1β-than in 4T1-tumor mice (Figure 5A and data not shown). To explore whether the MDSC subsets were involved in the reduction of NKG2D expression by NK cells, we sorted Ly6Clow MDSC and Ly6Cneg MDSC from the spleens of 4T1- or 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, respectively, and co-cultured them for 24 hours with splenocytes from naïve Rag2−/− mice in the presence of IL-2. We observed a stronger reduction of NKG2D expression by Rag2−/− NK cells when co-cultured with Ly6Cneg MDSC as compared with Ly6Clow MDSC (Figure 5B, top). Furthermore, transwell experiments revealed that NKG2D down-regulation was cell-cell contact dependent (Figure 5B, middle). We obtained similar results in vivo after adoptive transfer of purified Ly6Cneg MDSC and Ly6Clow MDSC, respectively, into naïve Rag2−/− mice. NK cells from Rag2−/− mice given Ly6Cneg MDSC displayed reduced expression of NKG2D 2 days after transfer, while NKG2D levels remained unchanged on NK cells from mice transplanted with Ly6Clow MDSC (Figure 5B, bottom).

Figure 5. MDSC from tumor-bearing mice affect NKG2D expression by NK cells.

NK cells were identified as indicated in Supplemental Figure 4. (A) Mean fluorescence intensity of NKG2D expression by BM (top) and splenic (bottom) CD122+NKp46+ NK cells from Rag2−/−mice bearing 4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β tumors (n=6–8), respectively. Results are shown relative to NK cells from naïve Rag2−/− (controls were set to 100%). One representative result from 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) NKG2D expression by CD122+NKP46+DX5+ cells among Rag2−/− splenocytes after 24h-co-culture with enriched Ly6Clow and Ly6Cneg MDSC (top), or after 24h-co-culture of naïve Rag2−/− splenocytes with enriched Ly6Cneg MDSC in transwell plates (middle). NKG2D expression by splenic NK cells (CD122+DX5+NKP46+) 3 days after adoptive transfer of enriched Ly6Cneg and Ly6Clow MDSC, respectively, into naïve Rag2−/− mice (bottom). Results from one representative experiment of three performed. (C) Activity of host NK cells measured in vivo after i.v. injection of 2x106 MACS-enriched Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from BM or spleen of mice bearing 4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β tumors as indicated. Activity is given relative to NK cells from non-injected control mice (n=4–5). Results from one representative experiment of two performed. (D) Ly6Clow MDSC, Ly6Cneg MDSC and non-MDSC were sorted from spleens of 4T1/IL-1β tumor-bearing mice and 5x105 cells of each population were injected i.v. into separate naïve BALB/c mice (n=5) and NK cell activity was measured in vivo. Results from one representative experiment of two performed. Error bars show SD. **p<0.01, *p<0.05 using two-sided Student’s t-test.

Together, these results indicated that MDSC subsets induce the down-regulation of NKG2D on the cell surface of NK cells and that Ly6Cneg MDSC were more potent in this process in vitro and in vivo.

Ly6Cneg MDSC inhibit NK cell function in vivo

We next addressed whether the down modulation of NKG2D expression was associated with functional impairment of NK cells in vivo. We adoptively transferred enriched MDSC isolated from BM and spleen of 4T1- or 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, respectively, intravenously into naïve BALB/c mice and challenged them 2–3 days later with luciferase-expressing YAC-1 target cells (Luc-YAC-1). As few as 7–8 hours thereafter NK cell activity was significantly lower in mice that had received MDSC from the BM and spleen of 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice as compared to those having received MDSC from 4T1-tumor bearing mice or Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from naive mice (Figure 5C). There was no clearance of Luc-YAC-1 cells in NK-deficient Rag2−/− IL-2Rβ−/− mice within the 8 hour period confirming NK cells as the effectors (Supplemental Figure 5). To determine whether NK inhibition was associated with a specific MDSC subset in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, we sorted three CD11b+ cell populations including Ly6Clow MDSC, Ly6Cneg MDSC, and an irrelevant population (non-MDSC) of Gr-1lowCD11b+Ly6Cint cells (data not shown) from the spleen of those mice and transferred them into naïve BALB/c mice. We used enriched CD11b+ BM cells from naïve mice as controls. Ly6Cneg MDSC induced a more potent suppression of the NK cell-mediated clearance of Luc-YAC-1 tumor cells than Ly6Clow MDSC, while Gr-1intCD11b+Ly6Clow/int (non-MDSC population) did not affect NK cell activity (Figure 5D). We did not observe a reduction in the numbers of NK cells in the different mice (data not shown), indicating that the reduction in NK cell activity was due to functional inhibition and not elimination of host NK cells.

Discussion

Oncogenic transformation and cancer progression have been intimately linked with inflammatory conditions (reviewed in [1]). Accordingly, we observed that 4T1 tumors developed faster in BALB/c mice when they over-expressed IL-1β, although both tumor lines exhibited similar growth kinetics in vitro (M.E. and R.N.A., unpublished observations and [11]). MDSC are known to accumulate in tumor bearing individuals, particularly under inflammatory conditions but they are also observed under various other pathological conditions, including infectious diseases [31]. The fact that multiple pathological conditions result in similar biological outcomes might explain the heterogeneity of MDSC but at the same time represents a challenge when studying these cells [31]. Understanding the pathways behind this heterogeneity under various conditions might allow unravelling the origin of their complexity. Here, we found that the enhanced accumulation of MDSC in mice bearing IL-1β-secreting 4T1 tumors was almost exclusively attributable to the expansion of a novel subset of MDSC. MDSC populations are mainly defined by their expression of Ly6C/G and CD11b, and this newly identified subset of PMN-MDSC was distinct from known MDSC subsets by its lack of Ly6C expression.

Our data provide strong evidence that IL-1β is involved in the regulation of the Ly6Cneg MDSC subset and suggest that the predominance of Ly6Cneg MDSC may enhance tumor progression in mice with 4T1/IL-1β tumors. Although the mode of action of this pleitotropic cytokine in this setting remains to be elucidated its ability to enhance the survival of PMN [32] might in part explain the strong accumulation of MDSC in these mice. A regulatory role for Ly6Cneg MDSC in mice with 4T1/IL-1β tumors is further supported by the delayed tumor growth after depletion of Gr-1+ cells. IL-10-dependent regulatory capacities of PMN in the settings of bacterial infections have recently been demonstrated [33]. Interestingly, LPS and INFγ activated MDSC from 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice were shown to produce significantly more IL-10 than those from 4T1-tumor bearing mice [16], yet, it remains to be shown whether this IL-10-dependent immune regulation occurs in the tumor environment [34]. Moreover, a novel subpopulation of human MDSC has recently been described possessing strong T cell suppressive potential. This subset was induced from normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells using cytokine mixtures containing IL-1β [35].

Ly6Cneg-MDSC and Ly6Clow-MDSC might represent separate lineages of MDSC characterized by a different susceptibility to factors in the tumor/host environment and equipped with a differential capacity to interfere with adaptive and innate immune responses. Alternatively, variations in the level of expression by PMN-MDSC of Ly6C might mark distinct states of differentiation within one MDSC lineage. Conceivably, such a differentiation within the tumor-microenvironment would likely be susceptible to tumor-derived signals, including TDFs. In support of this, it has recently been shown that different tumor microenvironments harbor distinct subsets of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) that could be classified according to the “M1” (antitumor) versus “M2” (protumor) macrophage activation paradigm [36] and all of which could be derived from a common monocyte precursor population [36]. A similar plasticity has been reported to exist within tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) that could polarize under the influence of TGF-β present in the tumor-microeenvironment towards antitumorigenic “N1” (when blocking TGF-β) versus protumorigenic “N2” (presence of TGF-β) subsets [37, 38]. Whether or not Ly6Cneg-MDSC can be classified according to this paradigm requires further experimental investigation.

NK cells are generally described as prototypic innate anti-tumor cells [27, 28] and an impaired NK cell compartment is associated with enhanced susceptibility to tumor development [39–41]. Consequently, a coherent ‘survival’ strategy of tumors might involve impairing the activity of NK cells, which is indeed frequently observed in tumor bearing individuals [18, 26–29, 42, 43]. The block in the development of NK cells from 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice is similar to that observed in mice bearing EL4 tumors [44] and reminiscent of NK cells from transgenic mice expressing the CD27-ligand CD70 ectopically on all B cells [45]. The reduced level of CD27 expression by NK cells might thus be an indication of engagement of CD27 by its ligand CD70 suggesting that constitutive CD27-CD70 interactions might cause the observed block in NK cell development in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice. As CD70 expression is restricted to activated T and B cells its expression might be induced upon exposure to IL-1β. However, NK cells in CD70-tg mice were not functionally impaired and expressed high levels of NKG2D, suggesting that the functional inhibition of NK cells in 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice is independent of the developmental defect.

Suppression of NK cell function in tumor bearing mice has been shown to involve MDSC-derived cytokines including TGF-β1 [18]. Yet, gene expression profiles of Ly6Clow MDSC and Ly6Cneg MDSC showed no significant difference in TGF-β mRNA expression (M.E. and R.N.A., unpublished observations), indicating that in our mouse model the observed reduction of NKG2D expression by NK cells was independent of TGF-β. Interestingly, NK cells from mice that constitutively express the NKG2D-ligand Rae-1ε exhibited a reduced cell surface expression of NKG2D and were functionally impaired, while their development was not affected [46]. Our finding that cell-to-cell contact was necessary for MDSC-induced down-modulation of NKG2D supports the concept that NKG2D-NKG2D ligand interactions contribute to functional inhibition of NK cells.

Nausch et al. demonstrated that some Mono-MDSC but not PMN-MDSC from RMA-S tumor-bearing mice activated NK cells via expression of the NKG2D-ligand Rae-1 [47]. Although we did not measure Rae-1 expression by Mono-MDSC this subset was by far outnumbered by the considerably expanding Ly6Cneg MDSC so that a potential activating activity of Mono-MDSC was likely overwhelmed by the suppressive activity of Ly6Cneg MDSC. Importantly, the RMA-S tumor model used by Nausch et al. differed from ours in that the granulocytic (PMN) MDSC in their studies expressed intermediate levels of Ly6C [47], suggesting that RMA-S tumor cells may not create a heightened inflammatory tumor environment.

In this work we identified a novel MDSC subpopulation characterized by its lack of Ly6C expression and its inhibition of NK cell function. Our findings extend the complexity of this immunosuppressive myeloid cell population and demonstrate how inflammation, via the production of IL-1β, regulates MDSC phenotype and function.

Material and Methods

Mice

BALB/c, BALB/c Rag2−/− [48], and BALB/c Rag2−/− IL-2Rβ−/− [49] mice were obtained from Charles River. Mice were maintained under SPF conditions at the Institut Pasteur and used at 4–10 weeks of age. In vivo experiments were approved by an institutional animal care committee at the Institut Pasteur and validated by the French Ministry of Agriculture.

IL-1β−/− and IL-1Ra−/− mice were described previously [50] and kindly provided by Prof. Yoichiro Iwakura (Tokyo University). IL-1 deficient mice were housed under SPF conditions at the animal facilities of the faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University. Mice were treated according to the NIH animal care guidelines adapted by the institutional animal committee.

Cells

The mammary carcinoma cell line 4T1was a kind gift of Dr. Fred Miller (Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit). 4T1/IL-1β were derived from 4T1 cells and maintained as described [11]. To generate Luc-YAC-1 cells YAC-1 cells were infected using TRIP Luc virus as described [51]. Luc-YAC-1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium complemented with 10% FBS, 10−5 M 2-ME and 100μg/ml penicillin.

Generation of tumors

Tumors were generated by injection of 4T1 and 4T1/IL-1β cells. 2 × 105 tumor cells were injected into the footpad of recipient mice. Tumor growth was assessed three times a week using a caliper.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions from the indicated organs were stained using commercially available antibodies listed in the ‘supplementary material and methods’ section, acquired on a FACSCanto II (FACSDiva software 5.02; BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Dead cells were excluded using Live/Death fixable Aqua cell stain (Invitrogen).

Imaging NK lytic activity in vivo

5×105 Luc-YAC-1 cells were injected into the footpad of recipient mice. Eight hours later mice were anesthetized (isoflurane) and injected intraperitoneally with 125mg/kg of D-luciferin (in PBS). Whole body images were taken 10 minutes after D-luciferin injection using an IVIS-100 imaging system (Xenogen). Luciferase signals were analysed using the Living Image 2.50/3 software (Xenogen). The total photon emission (Total-Flux, T.F.) values reflected the relative abundance of remaining Luc-YAC-1 cells in situ. Cytotoxicity of NK cells was determined by applying the following equitation to the measured luciferase activity:

Enrichment of MDSC population

CD11b+ MDSC from BM and spleen were MACS enriched using an AutoMACSpro (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity of PMN population was ~97% as determined by FACS, and approximately 95% for Ly6Clow and Ly6Cneg enriched populations obtained from 4T1 or 4T1/IL-1β-tumor bearing mice, respectively. Ly6Clow or Ly6Cneg and non-MDSC populations from spleen of 4T1/IL-1β-tumor mice were sorted on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Adoptive transfer of MDSC

Cells were enriched or sorted as described, resuspended in 200μl PBS and injected i.v. into recipient mice.

Depletion of Gr-1+ cells and IL-1 injection

Gr-1+ cells were depleted by injecting i.p. anti-Gr-1 antibodies (clone RB6-8C5; 250μg) twice a week. For Gemcitabine (Lilly) treatment, mice were injected i.p. twice a week as described [17]. Recombinant IL-1β (Peprotech; 200ng per mice) or recombinant IL-1Ra (Anakinra, Genetech; 50mg/kg) were injected daily i.p.

Statistical analyses

Significant differences in results were determined using the two-sided Student’s t-test; a * p<0.05 and ** p<0.01.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Pierre Charneau for providing TRIP Luc virus, Prof. Angel Porgador and Hélène Strick-Marchand for their stimulating discussions, Dr. Yoichiro Iwakura for the IL-1−/− mice, Fabrice Lemaitre for Gr-1 antibody purification, Dr. Delphine Guy-Grand for Giemsa staining.

Moshe Elkabets was supported by the Chateaubriand scientific pre- and post-doctorate fellowships 2007–2008, Nehemia-Lev-Zion excellent Ph.D scholarship and ISEF Foundation. Vera Ribeiro was supported by a fellowship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT). Suzanne Ostrand-Rosenberg was supported by NIH grants R01CA84232 and R01CA115880. James P. Di Santo and Christian Vosshenrich were supported by grants from the Institut Pasteur, Inserm, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, and FRM. Ron N. Apte was supported by the the Israel Ministry of Health Chief Scientist’s Office, the German-Israeli DIP collaborative program (Deutsche-Israelische Projektkooperation), the IsraelScience Foundation founded by the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) collaborative program with The German Cancer Center (DKFZ) and the FP7 EC consortium IFLA-CARE (Cancer and Inflammation).

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- MDSC

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

- PMN

Polymorphonuclear

- Mono

Monocytes

- Luc

luciferase

- TDF

tumor-derived factors

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apte RN, Voronov E. Is interleukin-1 a good or bad ‘guy’ in tumor immunobiology and immunotherapy? Imunol Rev. 2008;222:222–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voronov E, Shouval DS, Krelin Y, Cagnano E, Benharroch D, Iwakura Y, Dinarello CA, Apte RN. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2645–2650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shchors K, Shchors E, Rostker F, Lawlor ER, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. The Myc-dependent angiogenic switch in tumors is mediated by interleukin 1beta. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2527–2538. doi: 10.1101/gad.1455706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apte RN, Dotan S, Elkabets M, White MR, Reich E, Carmi Y, Song X, et al. The involvement of IL-1 in tumorigenesis, tumor invasiveness, metastasis and tumor-host interactions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:387–408. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krelin Y, Voronov E, Dotan S, Elkabets M, Reich E, Fogel M, Huszar M, et al. Interleukin-1beta-driven inflammation promotes the development and invasiveness of chemical carcinogen-induced tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1062–1071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, Betz KS, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song X, Krelin Y, Dvorkin T, Bjorkdahl O, Segal S, Dinarello CA, Voronov E, Apte RN. CD11b+/Gr-1+ immature myeloid cells mediate suppression of T cells in mice bearing tumors of IL-1beta-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8200–8208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunt SK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation induces myeloid-derived suppressor cells that facilitate tumor progression. J Immunol. 2006;176:284–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunt SK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10019–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunt SK, Clements VK, Hanson EM, Sinha P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation enhances myeloid-derived suppressor cell cross-talk by signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:996–1004. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivastava MK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Rodriguez P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010;70:68–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Han Y, Guo Q, Zhang M, Cao X. Cancer-Expanded Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Induce Anergy of NK Cells through Membrane-Bound TGF-{beta}1. J Immunol. 2009;182:240–249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawanobori Y, Ueha S, Kurachi M, Shimaoka T, Talmadge JE, Abe J, Shono Y, et al. Chemokine-mediated rapid turnover of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Blood. 2008;111:5457–5466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, Marigo I, Fernandez Gomez A, Mesa C, Geilich M, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:20–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cells, viruses and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:41–49. doi: 10.1038/35095564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Santo JP. Functionally distinct NK-cell subsets: developmental origins and biological implications. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2948–2951. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huntington ND, Vosshenrich CAJ, Di Santo JP. Developmental pathways that generate natural-killer-cell diversity in mice and humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nri2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierson BA, Miller JS. CD56+bright and CD56+dim natural killer cells in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia progressively decrease in number, respond less to stimuli that recruit clonogenic natural killer cells, and exhibit decreased proliferation on a per cell basis. Blood. 1996;88:2279–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sibbitt WL, Jr, Bankhurst AD, Jumonville AJ, Saiki JH, Saiers JH, Doberneck RC. Defects in natural killer cell activity interferon response in human lung carcinoma malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 1984;44:852–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu C, Yu S, Kappes J, Wang J, Grizzle WE, Zinn KR, Zhang HG. Expansion of spleen myeloid suppressor cells represses NK cell cytotoxicity in tumor-bearing host. Blood. 2007;109:4336–4342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dasgupta S, Bhattacharya-Chatterjee M, O’Malley BW, Jr, Chatterjee SK. Inhibition of NK cell activity through TGF-beta 1 by down-regulation of NKG2D in a murine model of head neck cancer. J Immunol. 2005;175:5541–5550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki E, Kapoor V, Jassar AS, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Gemcitabine selectively eliminates splenic Gr-1+/CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhances antitumor immune activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6713–6721. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Youn J, Gabrilovich DI. The biology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells: The blessing and the curse of morphological and functional heterogeneity. Eur J Immunol. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Majlessi L, Deriaud E, Leclerc C, Lo-Man R. Coactivation of Syk kinase and MyD88 adaptor protein pathways by bacteria promotes regulatory properties of neutrophils. Immunity. 2009;31:761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cassatella MA, Locati M, Mantovani A. Never underestimate the power of a neutrophil. Immunity. 2009;31:698–700. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL. Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:2273–2284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stangé G, Van den Bossche J, Mack M, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Research. 2010;70:5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS, Albelda SM. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani A. The Yin-Yang of tumor-associated neutrophils. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:173–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:329–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, Choy A, Gallardo F, Xiong N, Knoblaugh S, et al. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity. 2008;28:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ. NKG2D and cytotoxic effector function in tumor immune surveillance. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epling-Burnette PK, Bai F, Painter JS, Rollison DE, Salih HR, Krusch M, Zou J, et al. Reduced natural killer (NK) function associated with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and reduced expression of activating NK receptors. Blood. 2007;109:4816–4824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konjevic G, Mirjacic Martinovic K, Vuletic A, Jovic V, Jurisic V, Babovic N, Spuzic I. Low expression of CD161 and NKG2D activating NK receptor is associated with impaired NK cell cytotoxicity in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richards JO, Chang X, Blaser BW, Caligiuri MA, Zheng P, Liu Y. Tumor growth impedes natural-killer-cell maturation in the bone marrow. Blood. 2006;108:246–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Colvenaer V, Taveirne S, Hamann J, de Bruin AM, De Smedt M, Taghon T, Vandekerckhove B, et al. Continuous CD27 triggering in vivo strongly reduces NK cell numbers. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1107–17. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oppenheim DE, Roberts SJ, Clarke SL, Filler R, Lewis JM, Tigelaar RE, Girardi M, Hayday AC. Sustained localized expression of ligand for the activating NKG2D receptor impairs natural cytotoxicity in vivo reduces tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:928–937. doi: 10.1038/ni1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nausch N, Galani IE, Schlecker E, Cerwenka A. Mononuclear Myeloid-Derived “Suppressor” Cells express RAE-1 and activate NK cells. Blood. 2008;112:4080–4089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vosshenrich CAJ, Ranson T, Samson SI, Rosmaraki EE, Colucci F, Di Santo JP. Defining the role of γc-dependent cytokines in the development and differentiation of NK cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1213–1221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vosshenrich CAJ, Lesjean-Pottier S, Hasan M, Richard-Le Goff O, Corcuff E, Mandelboim O, Di Santo JP. CD11cloB220+ Interferon-producing Killer Dendritic Cells are activated NK cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2569–2578. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horai R, Asano M, Sudo K, Kanuka H, Suzuki M, Nishihara M, Takahashi M, Iwakura Y. Production of mice deficient in genes for interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-1alpha/beta, and IL-1 receptor antagonist shows that IL-1beta is crucial in turpentine-induced fever development and glucocorticoid secretion. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1463–1475. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zennou V, Serguera C, Sarkis C, Colin P, Perret E, Mallet J, Charneau P. The HIV-1 DNA flap stimulates HIV vector-mediated cell transduction in the brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:446–450. doi: 10.1038/88115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.