Abstract

Pulmonary actinomycosis is a rare disease frequently misdiagnosed, even by experienced clinicians, as primary or metastatic lung cancer or as other more conventional lung infections. It is often an unexpected disease that is basically detected only on cytological/histological examination. A case involving a patient who presented with a mass in the bronchial stump (of a previous pulmonary lobectomy) is described. Despite a strong suspicion of recurrent lung cancer, positron emission tomography confirmed a diagnosis of a suture-related bronchial actinomycosis.

Keywords: Bronchoscopy, CT, PET, Respiratory infection, Transbronchial needle aspiration

Abstract

L’actinomycose pulmonaire est une maladie rare souvent diagnostiquée à tort comme un cancer du poumon primaire ou métastatique ou d’autres infections pulmonaires plus classiques, et ce, même par des cliniciens expérimentés. C’est souvent une maladie inattendue qui n’est décelée qu’à l’examen cytologique ou histologique. Les auteurs décrivent le cas d’un patient qui a consulté et qui avait une masse au moignon bronchique (d’une lobectomie pulmonaire antérieure). Malgré une forte présomption de récurrence du cancer du poumon, la tomographie par émission de positrons a confirmé un diagnostic d’actinomycose bronchique liée à la suture.

Learning objectives

To recognize that pulmonary actinomycosis is an infectious disease with protean clinical and radiological presentations. Prolonged therapy with penicillin is the standard treatment. Positron emission tomography scan could be useful, especially when computed tomography scan features are nonspecific in supporting the pathological diagnosis and therapeutic response.

To understand that pulmonary actinomycosis should be included in the differential diagnosis with primary or metastatic lung malignancies, and other granulomatous and nongranulomatous pulmonary infections.

Pre-test

What are the predisposing factors for pulmonary actinomycosis?

How is pulmonary actinomycosis diagnosed?

CASE PRESENTATION

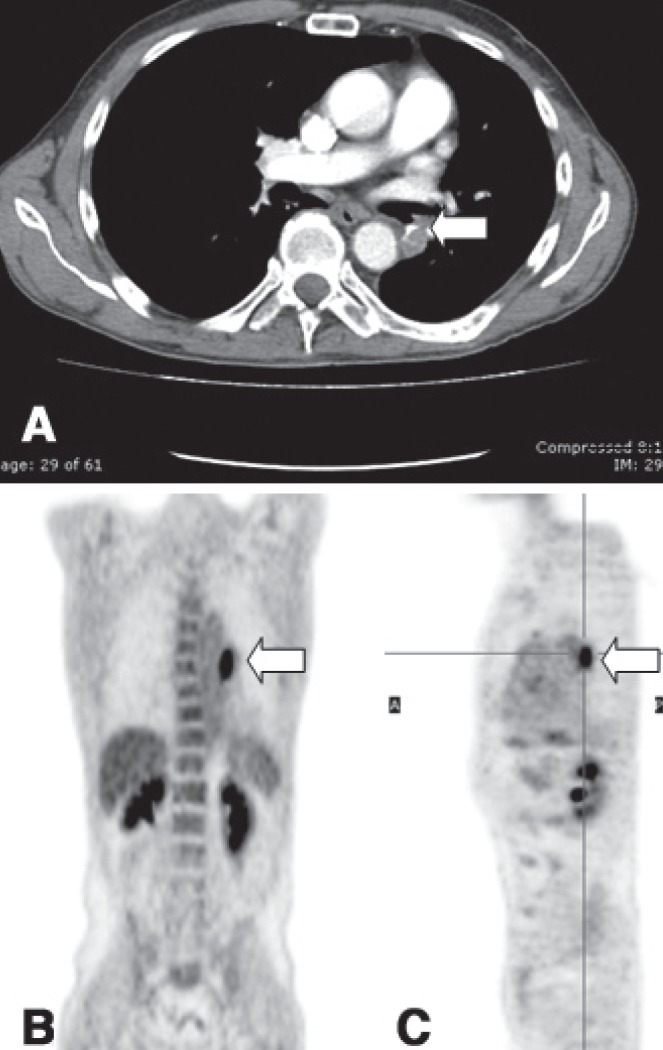

A 62-year-old male exsmoker with a history of throat cancer (in 2007) treated with radiotherapy and a left lower lobe resection for primary squamous cell carcinoma (April 2009) came to our attention for the presence of a mass in the surgical bronchial stump. The mass was discovered incidentally on computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1A) during follow-up for lung cancer. The lesion had a mean standard uptake value (SUV) of 6.8 (highly suspicious for malignancy) on fluorodeoxyglucose position emission tomography (PET) (Figures 1B and 1C).

Figure 1).

A Computed tomography scan performed before positron emission tomography (PET), showing a mass in the surgical stump of the previous left lower lobectomy (arrow). B and C PET scan both in coronal and sagittal planes showing metabolic uptake (standard uptake value 6.8) at the surgical stump of the previous left lower lobectomy (arrow)

The patient had no symptoms other than a dry cough due to gastroesophageal reflux secondary to previous radiotherapy, for which treatment with proton pump inhibitors was instituted. Pulmonary function tests were unremarkable.

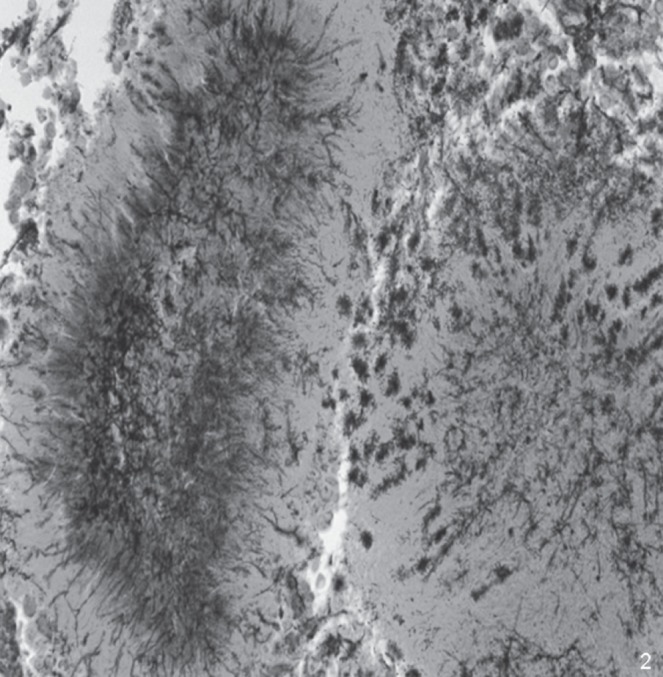

Bronchoscopy was negative, but a transbronchial needle aspiration performed on the surgical stump indicated the presence of methenamine silver-positive filamentous microorganisms consistent with Actimomyces species (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Grocott-Gomori staining showing sulfur granules of Actinomyces with prevalent neutrophil inflammation (methenamine silver stain, original magnification ×400)

Refusing intravenous treatment, the patient underwent oral antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin 3 g/day) and, despite advice to continue therapy for one year, he stopped the treatment after six months.

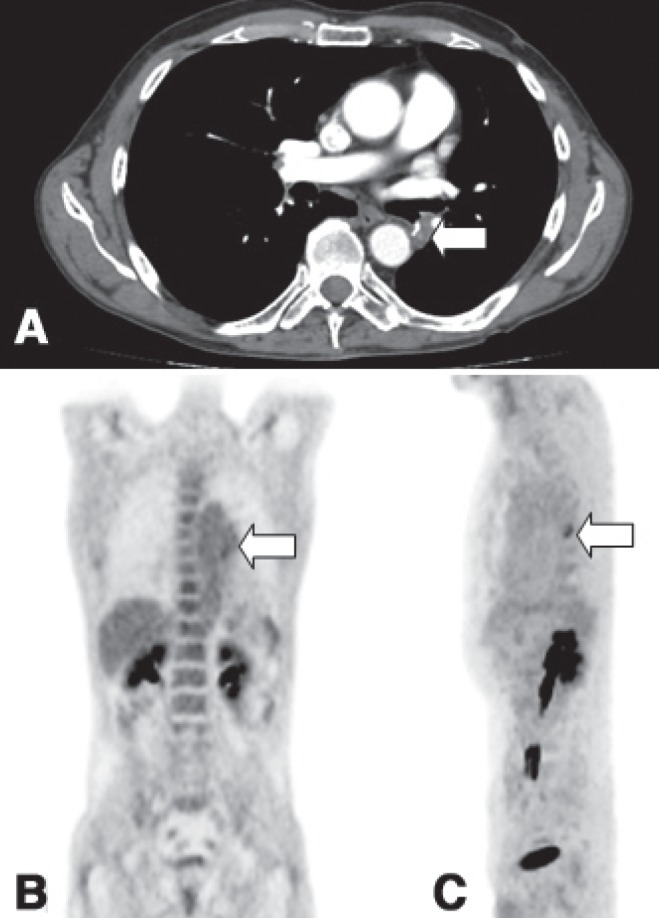

Nevertheless, imaging studies performed after discontinuation of antibiotic therapy were unchanged (Figure 3A), and a subsequent PET scan (one month later) showed a marked reduction of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (Figures 3B and 3C), with an SUV of 2.7. Although initially suspicious of cancer recurrence, this finding supported the cytological diagnosis of suture-related bronchial actinomycosis.

Figure 3).

A Computed tomography scan performed following six months of antibiotic therapy showing an unchanged mass (arrow). B and C Positron emission tomography scan both in coronal and sagittal planes showing reduction in metabolic uptake (standard uptake value 2.7) (arrow) after antibiotic therapy

DISCUSSION

Actinomyces are facultative, anaerobic Gram-positive, nonspore-forming, prokaryotic bacteria with a peculiar fungus-like morphology. Actinomyces normally live in the oropharynx, gastrointestinal tract and genital mucosa, but they can affect every organ of the body.

Pulmonary actinomycosis is a rare condition mainly involving the lung parenchyma and rarely appears as an endobronchial lesion. Its occurrence is commonly acquired through the aspiration of microorganisms from oropharyngeal or gastrointestinal secretions; infection via inhalation, hematogenous dissemination and direct extension from adjacent tissues may occur. Poor oral hygiene, dental problems, gastroesophageal reflux disease, oral trauma, infections, chronic debilitating diseases and other conditions (diabetes mellitus, neurological and psychiatric disease, virus-related or virus-free hepatitis, malnutrition, radiation, drug abuse, congenital or acquired immunosuppression) greatly predispose to pulmonary actinomycosis (1). Endobronchial foreign bodies (chicken and fish bones, grape seeds, beans, teeth, dental prostheses, alimentary material or wire sutures) or broncholiths increase the risk for Actinomyces colonization (2).

The clinical and radiological manifestations of thoracic actinomycosis are nonspecific and can simulate lung cancer, with cough, sputum and chest pain being the most common symptoms. Other chronic suppurative chest diseases (nocardiosis or tuberculosis) and malignancies (especially squamous cell carcinoma) are included in the differential diagnosis. Marked weight loss, malaise and high fever are suggestive of disseminated disease. Physical signs are equally nonspecific, except in advanced, untreated disease, when sinuses and fistulae may suggest the diagnosis. In some cases, the associated complications, such as pleural effusion or empyema (2), are the first presentation. It is not uncommon, however, for pulmonary actinomycosis, especially in its initial stages, to be completely asymptomatic and that its finding are purely coincidental, as occurred in the present case. Because asymptomatic recurrence of carcinoma at a bronchial stump may also occur, separation of these entities is challenging.

However, in experienced hands, some imaging features may suggest actinomycosis, but radiology alone is not diagnostic. Nonspecific symptoms and radiographic findings commonly lead to diagnostic delay. Cytohistological examination is the definitive test because the diagnosis of actinomycosis relies on pathologist recognition. In fact, Actinomyces are fastidious bacteria that are difficult to grow in culture (3). Cytology or histology show a necrotic, suppurative background with a predominance of neutrophils, plasma cells and histiocytes; in some cases, granulomatous inflammation with giant cells are present. In most cases, ‘sulfur granules’ with club-like, long, thin filamentous branching rods radiating from their periphery (so-called Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) are detected in inflammatory/necrotic tissue.

Penicillin remains the mainstay of treatment. Generally, intravenous penicillin is administered for two to six weeks, followed by oral therapy with amoxicillin (or penicillin V) for three to six months. In severe cases, oral therapy should be continued for at least 12 months. Acceptable alternatives to penicillin include tetracyclines, erythromycin and clindamycin (4). The availability of antibiotics has greatly improved the prognosis of all forms of actinomycosis. Presently, cure rates are high, and neither deformity nor death is common.

Similar to the few other reports in the literature (5,6), our study shows that PET scanning can support the pathological diagnosis of actinomycosis when the differential diagnosis includes lung cancer. Actinomycosis-related elevation of the SUV was probably due to acute inflammation involving all of the bronchial mucosal layers. The reduction of metabolic activity after specific antibiotic therapy significantly supports the diagnosis of actinomycosis. The search for predisposing factors, such as gastroesophogeal reflux and/or foreign bodies (eg, wire sutures), as in the present case, is important if this particular pathological condition is suspected.

Post-test

Widely-accepted predisposing factors for bronchopulmonary actinomycosis are poor dental hygiene, alcoholism, dental problems and interventions, oral trauma and infections, and various chronic debilitating diseases as well as diabetes mellitus, neurological and psychiatric diseases, gastrointestinal reflux and/or hiatus hernia, virus-related or virus-free hepatitis, malnutrition, radiation, drug abuse, congenital and acquired immunosuppression, endobronchial foreign bodies and medications.

The diagnosis of actinomycosis relies on pathological findings (cytology and/or histology), and frequently the pathologist is the first to recognize this microorganism. Actinomyces, due to their anaerobic nature, are difficult to grow in culture and microbiological analyses are often pointless.

The Canadian Respiratory Journal is now accepting submissions for a new Clinico-Pathologic Conferences series. These will be based on case presentations that illustrate important learning issues involving diagnosis and/or management decisions, and should be supported by images from appropriately applied diagnostic and/or prognostic testing which could include: 1) Lung function tests; 2) Exercise testing; 3) X-rays or computed tomography scans; 4) Ultrasound (including endobronchial ultrasound); 5) Positron emission tomography scans; or 6) Bronchoscopy/thoracoscopy.

All case reports appearing in the Canadian Respiratory Journal will conform to this format and manuscripts should be structured as described in the Instructions to Authors. A maximum of four images can be submitted and the number of references should not usually exceed 10. The submission will be peer reviewed and may be edited by our editorial team.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreani A, Cavazza A, Marchioni A, Richeldi L, Paci M, Rossi G. Bronchopulmonary actinomycosis associated with hiatal hernia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:123–8. doi: 10.4065/84.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mabeza GF, Macfarlane J. Pulmonary actinomycosis. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:545–51. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00089103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smego RA, Jr, Fogli G. Actinomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1255–61. doi: 10.1086/516337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yildiz O, Doganay M. Actinomycosis and Nocardia pulmonary infections. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:228–34. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000219273.57933.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokuyasu H, Harada T, Watanabe E, et al. A case of endobronchial actinomycosis evaluated by FDG-PET. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;46:650–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho L, Seto J, Jadvar H. Actinomycosis mimicking anastomotic recurrent esophageal cancer on PET-CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:646–7. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000238193.34543.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]