Abstract

Dysfunction of the intestinal epithelium is believed to result in excessive translocation of commensal bacteria into the bowel wall that drives chronic mucosal inflammation in Crohn's disease; an incurable inflammatory bowel disease in humans characterized by inflammation of the terminal ileum1. Beside the physical barrier established by the tight contact of cells, specialized epithelial cells such as Paneth cells and goblet cells provide innate immune defence functions by secreting mucus and antimicrobial peptides which hamper access and survival of bacteria adjacent to the epithelium2. Epithelial cell death is a hallmark of intestinal inflammation and has been discussed as a pathogenic mechanism driving Crohn's disease (CD) in humans3. However, the regulation of epithelial cell death and its role in intestinal homeostasis remains poorly understood.

Here we demonstrate a critical role for caspase-8 in regulating necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) and terminal ileitis. Mice with a conditional deletion of caspase-8 in the intestinal epithelium (Casp8ΔIEC) spontaneously developed inflammatory lesions in the terminal ileum and were highly susceptible to colitis. Casp8ΔIEC mice lacked Paneth cells and showed reduced numbers of goblet cells suggesting dysregulated anti-microbial immune cell functions of the intestinal epithelium. Casp8ΔIEC mice showed increased cell death in the Paneth cell area of small intestinal crypts. Epithelial cell death was induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -α, was associated with increased expression of receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and could be inhibited upon blockade of necroptosis. Finally, we identified high levels of RIP3 in human Paneth cells and increased necroptosis in the terminal ileum of patients with Crohn's disease, suggesting a potential role of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of this disease. Taken together, our data demonstrate a critical function of caspase-8 in regulating intestinal homeostasis and in protecting IEC from TNF-α induced necroptotic cell death.

Caspase-8 is a cystein protease critically involved in regulating cellular apoptosis. Upon activation of death receptors, including TNF-receptor and Fas, caspase-8 is activated by limited autoproteolysis and the processed caspase-8 subsequently triggers the caspase cascade which finally leads to apoptotic cell death. Caspase-mediated apoptosis is important for the turnover of IEC and for shaping the morphology of the gastrointestinal tract4. Furthermore, recent data have indicated a role of caspase-mediated apoptosis of IEC in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis5,6.

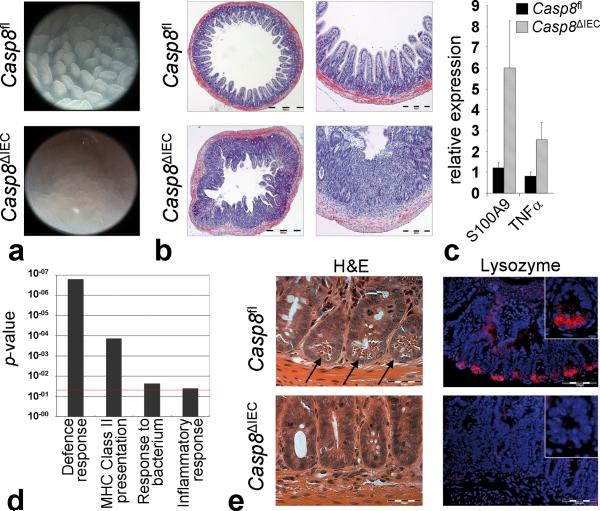

To study the function of caspase-8 in the gut, we generated mice with an intestinal epithelial cell specific deletion of caspase-8 (Casp8ΔIEC). Accordingly, mice with floxed caspase-8 alleles were bred with mice expressing the Cre-recombinase under the control of the IEC-specific villin promoter. Specific deletion of caspase-8 in IEC was confirmed by PCR and Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Casp8ΔIEC mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratios and developed normally, although weighing on average slightly less than control littermates at 8 weeks of age (data not shown). Despite the paradigm that apoptosis is important for regulating epithelial cell numbers4, histological and morphometrical analysis of the jejunum and colon of Casp8ΔIEC mice showed no overt changes of tissue architecture or apoptosis dysregulation (Supplementary Figs. 1d-f, 2). While this suggested that caspase-8 is not essential for the structural development of the gut, high resolution endoscopy showed erosions in the terminal ileum but not in the colon of Casp8ΔIEC mice (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1c). Histological analysis demonstrated marked destruction of the architecture and signs of inflammation including bowel wall thickening, crypt loss and increased cellularity in the lamina propria (Fig. 1b) in more than 80% of all ileal specimens. This finding of spontaneous ileitis in the absence of caspase-8 in IEC was further supported by increased expression of the inflammation markers S100A9 and TNF-α and by elevated infiltration of the lamina propria with CD4+ T cells and granulocytes (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Casp8ΔIEC mice spontaneously develop ileitis and lack Paneth cells.

(a) Representative endoscopic pictures and (b) H&E stained cross sections showing villous erosions in the terminal ileum of Casp8ΔIEC. (c) RT-PCR showing increased level of inflammatory markers in the terminal ileum of Casp8ΔIEC mice (6 mice per group +SEM, relative to HPRT). (d) Gene ontology analysis of genes significantly downregulated in gene chip analysis of IEC from 3 control and 3 Casp8ΔIEC mice. (e) Ileum cross sections stained with H&E and lysozyme for Paneth cells (inset = single crypt at higher magnification). Arrows indicate crypt bottom with Paneth cells.

To investigate whether caspase-8 deficiency sensitizes mice to experimental intestinal inflammation in the large bowel, we subjected Casp8ΔIEC and control mice to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS), a well established model of experimental colitis. Strikingly, Casp8ΔIEC mice but not control mice showed high lethality and lost significantly more weight than control mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). All Casp8ΔIEC but none of the control mice developed rectal bleeding, endoscopic and histological signs of very severe colitis with epithelial erosions, a finding which was confirmed by quantitative PCR for the IEC marker villin. Together, our data indicate that a lack of caspase-8 in IEC renders mice highly susceptible to spontaneous ileitis and experimentally induced colitis.

To screen for molecular mechanisms that sensitize Casp8ΔIEC mice for intestinal inflammation, we next performed whole genome gene chip analysis of IEC from unchallenged control and Casp8ΔIEC mice. Of the 45,000 expression tags analyzed, 197 were significantly downregulated and 136 upregulated in Casp8ΔIEC mice (fold change > 2.0, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of downregulated genes showed that several biological pathways were impaired in Casp8ΔIEC mice as compared to littermate controls, with the GO terms “defence response” and “MHC class II antigen presentation” reaching very high levels of significance (Fig. 1d). Within the group of genes upregulated in Casp8ΔIEC mice, no GO term reached significance levels. Strikingly, within the defence response gene set, genes belonging to the family of antimicrobial peptides including several defensins, lysozyme and phospholipases were amongst the most strongly downregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 5a), suggesting defects in the antimicrobial defence of the intestinal epithelium in the absence of epithelial caspase-8. Expression of antimicrobial peptides is a hallmark of Paneth cells, epithelial derived cells which are located at the base of crypts of Lieberkuehn in the small intestine7. Within Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides are stored in cytoplasmatic granules, from which they can be released into the gut lumen, thereby contributing to intestinal host defences. Strikingly, Casp8ΔIEC mice showed a complete absence of cells with secretory granules and lysozyme expression at the crypt base of the small intestine, suggesting that Paneth cells are lacking in the gut of these animals (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, the number of mucus secreting goblet cells was reduced, as indicated by staining with Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin 1 (UEA-1), a lectin binding to glycoproteins characteristic for these cells (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In contrast, we observed no changes in the appearance of enteroendocrine cells or absorptive enterocytes, as indicated by staining for chromogranin-A or alkaline phosphatase, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The lack of Paneth cells and partial lack of goblet cells was confirmed by quantitative gene expression analysis showing diminished expression of Paneth cell and goblet cell specific genes, while expression of genes specific for enteroendocrine cells, enterocytes and progenitor cells was unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Thus, collectively, our data implicate that deficient expression of caspase-8 in the intestinal epithelium results in diminished Paneth and goblet cell numbers and hence may lead to defects in antimicrobial host defence and terminal ileitis.

In addition to controlling apoptosis, there is growing evidence that caspase-8 regulates several non-apoptotic cellular mechanisms including proliferation, migration and differentiation8,9. Accordingly, caspase-8 has been shown to promote the terminal differentiation of macrophages and keratinocytes10. Thus, we reasoned that caspase-8 might support intestinal immune homeostasis by promoting the terminal differentiation of Paneth and goblet cells. To verify this hypothesis, we performed long term organoid cultures of small intestinal crypts in vitro as previously introduced by Sato et al.11. Isolated crypts from the small intestine underwent multiple crypt fissions forming large organoids in both control and Casp8ΔIEC mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In striking contrast to the absence of Paneth cells in crypts from Casp8ΔIEC mice in vivo, organoids grown from these crypts in vitro over a period of 1 to 4 weeks showed Paneth cells indistinguishable in localization and number from organoids cultured from control littermate mice (Fig. 2a). PCR-analysis confirmed deletion of the caspase-8 allele in Paneth cell positive organoids derived from Casp8ΔIEC mice (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Thus, our data suggest that caspase-8 is not required for the differentiation of IEC into Paneth cells, but that a factor present in vivo either inhibited the development of or ablated Paneth cells in the absence of caspase-8 expression.

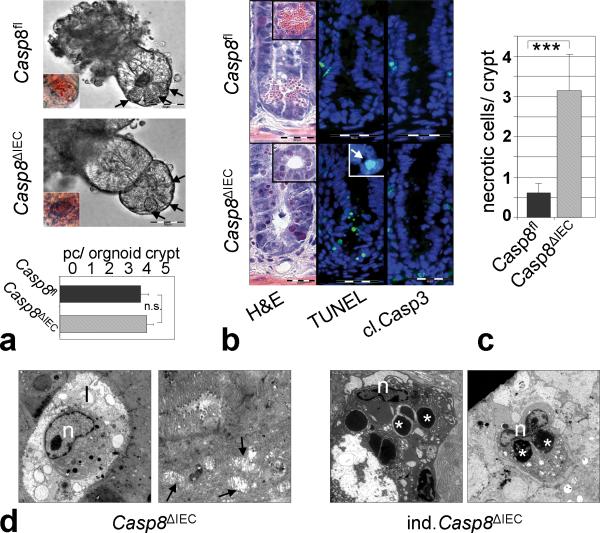

Figure 2. Increased caspase-8 independent cell death within crypts of Casp8ΔIEC mice.

(a) Representative pictures of gut organoids. Inset = Eosin staining indicating Paneth cells. Graph: Number of Paneth cells (pc) per organoid crypt (n=24) +SEM. (b) Crypt cross sections from the small intestine of control and Casp8ΔIEC mice stained with H&E. TUNEL ( Inset: condensed nuclei) and caspase-3. (c) Quantification of necrotic cells per crypt + SD of control (n=9) and Casp8ΔIEC (n=14) mice. (d) Electron microscopic pictures of dying crypt cells in Casp8ΔIEC mice and inducible Casp8ΔIEC. Asterisks, Paneth cell granules; “n”, nuclei; “l”, crypt lumen; Arrows: mitochondrial swelling.

Indeed, Casp8ΔIEC mice showed a large number of dying epithelial cells at the crypt base with pyknotic nuclei and a shrunken eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2b), implicating that caspase-8 deficient Paneth and goblet cells might be sensitive to cell death. Dying crypt cells usually lacked typical apoptotic body formation, suggesting necrotic rather than apoptotic cell death. This conclusion was supported by the observation that dying cells were TUNEL positive, but showed no activation of caspase-3 (Fig. 2b). The number of necrotic cells at the crypt base was significantly higher in Casp8ΔIEC mice as compared to control mice (Fig. 2c). Finally, electron microscopy of the crypt area demonstrated cells with typical features of necrosis including mitochondrial swelling and extensive vacuole formation while typically lacking blebbing usually associated with apoptosis (Fig. 2d). Importantly, many cells with features of necrosis also showed electron dense granules indicating necrotic Paneth cells. This conclusion was supported by electron microscopy of mice in which the caspase-8 deletion was induced in adult mice by injection with Tamoxifen (inducible Casp8ΔIEC) to detect early effects of caspase-8 deletion. Taken together, our data suggest that the lack of caspase-8 sensitizes Paneth cells in the crypts of the small intestine to necrotic cell death.

TNF-α stimulated death receptor signaling has been described to promote necrosis in a number of different target cell types, especially when apoptosis was blocked using caspase-inhibitors12,13. We therefore reasoned that in the absence of caspase-8, TNF-α signaling might lead to excessive crypt cell death. To test this hypothesis, we intravenously (i.v.) administered mice with TNF-α using a dose which is not lethal to normal mice. While all control mice were still alive after 5 hours, Casp8ΔIEC mice showed significantly more pronounced hypothermia and very high lethality (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). Histological analysis demonstrated villous atrophy and severe destruction of the small bowel of Casp8ΔIEC mice as compared to control littermates and an increased number of dying epithelial cells, as indicated by the pyknotic nuclei seen in the H&E stain of crypts and cells in the crypt lumen (Supplementary Fig. 7c-e). Similar to unchallenged mice, dying crypt cells were negative for active caspase-3 but positive for TUNEL staining (Supplementary Fig. 8a-c), suggesting that in the absence of caspase-8, TNF drives excessive necrosis of epithelial cells.

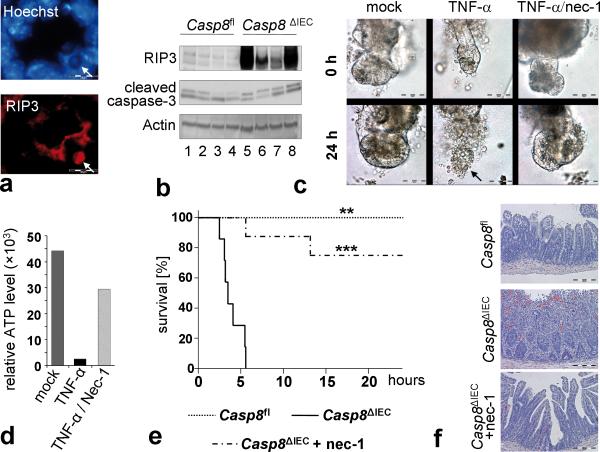

Recent data from other experimental systems have shown that inhibition of caspase activity in genetic models or by using specific caspase inhibitors can result in an apoptosis-independent type of programmed necrosis called necroptosis14. Necroptosis has been shown to be mediated by the kinases RIP1 and RIP315,16. Upon induction of necrosis, RIP3 is recruited to RIP1 to establish a necroptosis inducing protein complex. RIP3 seems to be essential for the molecular mechanisms driving necroptosis and expression of RIP3 has been demonstrated to correlate with the sensitivity of cells towards necroptosis17,18. Moreover, deletion of RIP3 has recently been shown to rescue the lethal phenotype of general caspase-8 deficient mice by blocking cell death19,20. Strikingly, expression of RIP3 mRNA, but not RIP1 mRNA was significantly increased in IEC isolated from unchallenged Casp8ΔIEC mice as compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 9). Condensed nuclei as observed in the crypts of Casp8ΔIEC mice stained for RIP3 using immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 8e). Moreover RIP3 was overexpressed in the small intestine of TNF-α treated Casp8ΔIEC mice when compared to control littermate mice (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 8d), suggesting that the lack of caspase-8 in the intestinal epithelium might sensitize IEC to RIP-mediated necroptotic cell death. In line with this hypothesis, RIP3 staining was detected especially in cells at the crypt base (Supplementary Fig. 10). Moreover, significant levels of TNF-α were detected in lamina propria cells adjacent to crypt IEC and both TNF-α and RIP3 expression were highest in the terminal ileum.

Figure 3. Inhibition of TNF-α induced epithelial necroptosis in Casp8ΔIEC mice.

(a) Representative RIP3 staining colocalizing with condensed nuclei at the crypt bottom of Casp8ΔIEC mice. (b) Western blot for RIP3 and cleaved caspase-3 of IEC lysates isolated from TNF-α treated control and Casp8ΔIEC mice. Actin served as a control. (c) Representative microscopic pictures and (d) cell viability of Casp8ΔIEC organoids treated for 24 h with TNF-α +/- necrostatin-1. (e) Survival and (f) H&E stained small intestine cross sections of control (n=5), Casp8ΔIEC (mock pretreated, n=7) and Casp8ΔIEC (nec-1 pretreated, n=8) mice after intravenous injection of TNF-α. Asterisks show significance level relative to Casp8ΔIEC without nec-1. All experiment were performed at least 3 times with similar results.

RIP-mediated necroptosis can be blocked in vitro and in vivo by using necrostatin-1 (nec-1), an allosteric small-molecule inhibitor of the RIP1 kinase21. Thus we reasoned that nec-1 might prevent TNF-α induced epithelial necroptosis and lethality in Casp8ΔIEC mice. Indeed, in vitro, small intestinal organoid cultures from Casp8ΔIEC mice but not from control mice exhibited necrosis within 24 hours after addition of TNF-α to the tissue culture. However, when cell cultures were pre-treated with nec-1, organoid necrosis was blocked (Fig. 3c, d). Moreover, pre-treatment with nec-1 significantly reduced TNF-α induced lethality and small intestinal tissue destruction in Casp8ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3e, f). Collectively, our data suggest that deficient caspase-8 expression renders Paneth cells susceptible to TNF-α induced necroptosis highlighting a regulatory role of caspase-8 in antimicrobial defence and in maintaining immune homeostasis in the gut.

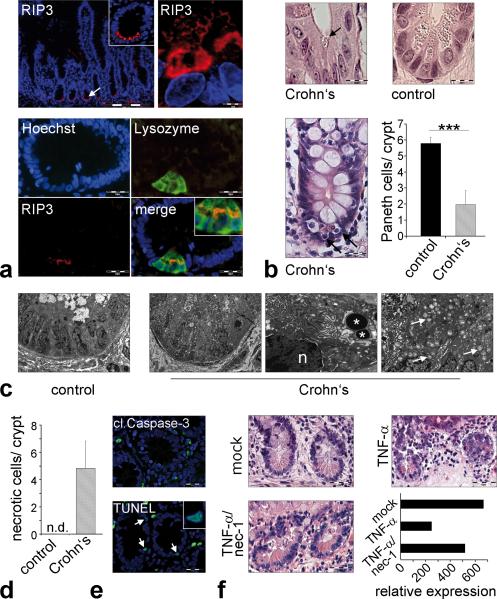

Interestingly, defects in Paneth cell function and in the expression of antimicrobial peptides have been described in Crohn's disease patients and accumulating evidence support a role for Paneth cells in the pathogenesis of this disease1,7,22. As anti-TNF-α treatment is successfully used in the therapy of patients with Crohn's disease, we hypothesized that similar to Casp8ΔIEC mice, human Paneth cells might be susceptible to TNF-α induced necroptosis. Paneth cell dysfunction has been reported in mice deficient of autophagy genes such as Atg16L1, a gene associated with Crohn's disease susceptibility3. Moreover, depletion of Paneth cells in the small intestine has been reported in patients with ileal Crohn's disease and patients with ulcerative colitis involving the terminal ileum23. Strikingly, immunohistochemistry of samples derived from the terminal ileum of human patients undergoing endoscopic examination revealed high expression of RIP3 exclusively in Paneth cells (Fig. 4a), but not in other intestinal epithelial cell types. Importantly, analysis of histological samples from the terminal ileum of control patients and patients with active Crohn's disease showed a significant decrease in the number of Paneth cells and high numbers of dying cells with shrunken eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 4b) at the crypt base, similarly to Casp8ΔIEC mice. Electron microscopy of the Paneth cell area in the terminal ileum of patients with CD, showed increased necrotic cell death, as indicated by abundant organelle swelling, vacuole formation and the lack of blebbing (Fig. 4c+d). Moreover, crypt epithelial cells in areas of acute inflammation usually were TUNEL positive but lacked staining for active caspase-3 (Fig. 4e). Finally, ileal biopsies from control patients showed Paneth cell loss in the presence of high levels of exogenous TNF-α, an effect that was reversible by co-incubation with necrostatin-1 (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 11a). Thus, our data suggest that necroptosis of Paneth cells is a feature of Crohn's disease. Since it has recently been shown that anti-TNF treatment partially restores the deficient expression of antimicrobial peptides in Crohn's disease patients24, our data suggest that the high levels of TNF-α present in the lamina propria of the inflamed ileum induce Paneth cell necroptosis and may provide a molecular explanation for the defects in antimicrobial defence observed in these patients.

Figure 4. RIP-mediated necroptosis of Paneth cells in patients with Crohn's disease.

(a) Representative RIP3 immunostaining of the terminal ileum (healthy patient). TOP: RIP3 expression in human Paneth cells. BOTTOM: Colocalization of lysozyme and RIP3 in Paneth cells. (b) H&E staining of crypts in the terminal ileum. Arrows indicate crypt cells with shrunken eosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei. GRAPH: Number of Paneth cells (+SD) per crypt in control patients (n=7) and patients with active Crohn's disease (n=4). (c) Electron microscopy of the terminal ileum of control and Crohn's disease patient. Asterisks highlight Paneth cell granules, “n” indicates nucleus. (d) Number of crypt cells (+SD) showing organelle swelling but regular nuclei as signs of necroptosis. EM pictures of 4 patients were analyzed. (e) Representative immunofluorescence staining for TUNEL and active caspase-3 in crypts of the terminal ileum of a CD-patient. (f) H&E staining of biopsies from the small intestine of control patients stimulated in vitro with either DMSO (mock), TNF-α alone or in combination with necrostatin-1. GRAPH: Quantitative expression level of the Paneth cell marker lysozyme relative to HPRT. Data from one representative experiment out of 2 is shown. Arrow indicate Paneth cells (a,e) or mitochondrial swelling (c).

In summary our data uncover an unexpected function of caspase-8 in regulating necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells and in maintaining immune homeostasis in the gut. Caspase-8 deficient mice had no defect in overall gut morphology, demonstrating that cell death independent from the extrinsic apoptosis pathway can regulate intestinal homeostasis. Indeed, studies using electron microscopy have shown various different cell death morphologies in the small intestine including morphological changes usually seen in necrosis such as cell swelling and a degradation of organelles and membranes25. Caspase-8 deficient mice completely lacked Paneth cells, suggesting that these cell types are highly susceptible to necroptosis. Crohn's disease patients frequently show reduced Paneth and goblet cell numbers and reduced expression of Paneth cell derived defensins in areas of acute inflammation, suggesting that necroptosis might be involved in the pathogenesis of human IBD22. Indeed, we were able to demonstrate constitutive expression of RIP3, a kinase sensitizing cells to necroptosis17,18, in human Paneth cells. Moreover cells undergoing necroptosis were found at the crypt base in patients with Crohn's disease and Paneth cell death could be inhibited by blocking necroptosis.

Caspase-8 has recently been shown to suppress RIP3-RIP1-kinase-dependent necroptosis following death receptor activation14,17,18. This has been highlighted by genetic studies demonstrating that deletion of RIP3 can rescue the embryonic lethality observed in mice with a general deletion of caspase-819,20. Thus it is getting increasingly clear, that caspase-8 has an essential function in controlling RIP-3 mediated necroptosis. On the molecular level, caspase-8 has been demonstrated to proteolytically cleave and inactivate RIP1 and RIP3 thereby regulating the initiation of necroptosis20. Currently, to our knowledge, no study has demonstrated caspase-8 as an IBD-linked gene using genetic studies. However, caspase-8 was expressed at relatively low levels in the crypt area of the human terminal ileum and activation of caspase-8 was only seen sporadically along the crypt-villous axis (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Given the low expression of caspase-8 and high expression of RIP3 at the base of crypts, cells residing in this area may be susceptible to necroptosis upon stimulation with death receptor ligands such as TNF-α.

TNF-α is an important contributor to the pathogenesis of IBD and treatment with biological drugs targeting TNF-α is effective in patients with Crohn's disease. Interestingly, mice overproducing TNF-α develop transmural intestinal inflammation with granulomas primarily in the terminal ileum, similar to Crohn's disease26. TNF-α was a strong promoter of intestinal epithelial necroptosis in our experiments. Since anti-TNF treatment has been shown to restore expression of certain antimicrobial peptides24, it is tempting to speculate, that TNF-α induced necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells contributes to the pathogenesis of IBD and that Paneth and goblet cell sensitivity towards TNF induced necroptosis may be an early event in IBD development. However, it remains to be determined, whether Paneth cell necroptosis in Crohn's disease patients is quantitatively sufficient to affect the disease process. Further studies will be needed to decipher the precise regulatory network of death receptors, RIP kinases and caspase-8 at the crypt base and it will be important to elucidate whether genetic, epigenetic or post-translational mechanisms restrict expression or activation of caspase-8 in IBD patients. Ultimately, our data for the first time demonstrate necroptosis in the terminal ileum of patients with Crohn's disease and suggest that regulating necroptosis in the intestinal epithelium is critical for the maintenance of intestinal immune homeostasis. Targeting necroptotic cellular mechanisms emerges as a promising option in treating patients with IBD.

Methods summary

Mice carrying a loxP-flanked caspase-8 allele (Casp8fl) and Villin-Cre mice were described earlier27-29. IEC-specific caspase-8 knockout mice were generated by breeding Casp8fl mice to Villin-Cre or Villin-CreERT2 mice. Experimental colitis was induced with 1-1.5% dextrane sodium sulfate (DSS, MP Biomedicals) in the drinking water for 5-10 day. Colitis development was monitored by analysis of weight, rectal bleeding and colonoscopy as previously described30. In some experiments, mice were injected intravenously with TNF-α (200 ng/g body weight, Immunotools) plus/minus necrostatin-1 (1.65 μg/g body weight, Enzo). Histopathological analysis was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue after H&E staining. Immunofluorescence of cryosections was performed using the TSA-Kit as recommended by the manufacturer (PerkinElmer). For electron microscopy, glutaraldehyde fixed material was used. Ultrathin sections were cut and analyzed using a Zeiss EM 906 (Zeiss). Paraffin-embedded patient specimens were obtained from the Institute of Pathology and endoscopic biopsies were collected in the Department of Medicine 1 (Erlangen University). The collection of samples was approved by the local ethical committees and each patient gave written informed consent. For organoid culture, intestinal crypts were isolated from mice and cultured as previously described11. Organoid growth was monitored by light microscopy. IEC were isolated as previously described5. For gene chip experiments, total RNA of IEC was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and hybridised to the Affymetrix mouse 430 2.0 chip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Gene ontology based analyses were performed using the online tool Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). Caspase-3/-7 activity was measured using the Caspase-Glo3/7 Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Methods

Mice

Mice carrying a loxP-flanked caspase-8 allele (Casp8fl) and Villin-Cre mice were described earlier27-29. Intestinal epithelial specific caspase-8 knockout mice were generated by breeding floxed caspase-8 mice to either Villin-Cre or Villin-CreERT2 mice. For the induction of the CreERT2 line (Villin-CreERT2 × Casp8fl), Tamoxifen (50 mg/ml ethanol, Sigma) was emulsified in sunflower oil at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Mice were daily injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of Tamoxifen. In all experiments, littermates carrying the loxP-flanked alleles but not expressing Cre recombinase were used as controls. Cre mediated recombination was genotyped by polymerase chain reaction on tail DNA. Experimental colitis was induced by treating mice with 1-1.5% dextrane sodium sulfate (DSS, MP Biomedicals) in the drinking water for 5-10 day. DSS was exchanged every other day. In some experiments, mice were injected i.v. with rm-TNF (200 ng/g body weight, Immunotools) plus/minus necrostatin-1 (1.65 μg/g body weight, Enzo). Mice were examined by measuring body temperature, weight loss and monitoring development of diarrhea. Colitis development was monitored by analysis of rectal bleeding and high resolution mouse video endoscopy as previously described29. Mice were anesthetized with 2–2.5% isoflurane in oxygen during endoscopy. Mice were routinely screened for pathogens according to FELASA guidelines. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Erlangen.

Human samples

Paraffin-embedded specimens from the terminal ileum of control patients and patients with active Crohn's disease were obtained from the Institute of Pathology of the University Clinic Erlangen. The specimens had been taken from routine diagnostic samples and patient data had been made anonymous. EM and tissue culture experiments were performed with endoscopic biopsy specimens collected in the endoscopy ward of the Department of Medicine 1. The collection of samples was approved by the local ethical committee and the institutional review board of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and each patient gave written informed consent.

Histology, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy

Histopathological analysis was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue after H&E staining. Immunofluorescence of cryosections was performed using the TSA Cy3 system as recommended by the manufacturer (PerkinElmer). Fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) and confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, Wetzlar, Germany) was used for analysis. The following primary antibodies were used: CD4 (BD, San Diego, CA), myeloperoxidase (Zymed Labs, San Francisco, CA), F4/80 (MD Bioscience, St. Paul, MN), caspase-8 (Sigma), cleaved caspase-8, cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology), lysozyme, chromogranin-A (Invitrogen), human RIP3 (Abcam), mouse RIP3 (AbD Serotec, Dusseldorf, Germany) and TNF-α (Pharmingen). Slides were then incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies (Dianova, Darmstadt, Germany). The nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 3342 (Invitrogen). Cell death was analyzed using CaspACE FITC-VAD-FMK (Promega) for early apoptosis and the in situ cell death detection kit (Roche) for TUNEL. For electron microscopy, glutaraldehyde fixed material was used. After embedding in Epon Araldite, ultrathin sections were cut and analyzed using a Zeiss EM 906 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Crypt isolation and organoid culture

Organ culture of freshly isolated human small intestinal biopsies was performed in RPMI medium (Gibco). For organoid culture, crypts were isolated from the small intestine of mice and cultured for a minimum of 7 days as previously described11. In brief, crypts were isolated by incubating pieces of small intestine in isolation buffer (phosphate buffered saline without calcium and magnesium (PBSO), 2 mM EDTA). Crypts were then transferred into matrigel (BD Bioscience) in 48 well plates and 350 μl culture medium (Advanced DMED/F12 (Invitrogen), containing HEPES (10 mM, PAA), GlutaMax (2 mM, Invitrogen), Penicillin (100 U/ml, Gibco), Streptomycin (100 μg/ml, Gibco), murine EGF (50 ng/ml, Immunotools), recombinant human R-spondin (1 μg/ml, R&D Systems), N2 Supplement 1x (Invitrogen), B27 Supplement 1x (Invitrogen), 1 mM N-acetylcystein (Sigma-Aldrich) and recombinant murine Noggin (100 ng/ml, Peprotech)). Organoid growth was monitored by light microscopy. In some experiments, human biopsies or organoids were treated with recombinant mouse TNF-α (25 ng/ml, Immunotools), recombinant human TNF-α (50 ng/ml, Immunotools), necrostatin-1 (30 μM, Enzo) or caspase-8 inhibitor (50 μM, Santa Cruz). Cell Viability of organoids was analyzed indirectly by quantification of relative ATP level with the CellTiter-Glo assay from Promega according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was measured on the microplate reader infinite M200 (Tecan).

IEC isolation and immunoblotting

IEC were isolated in an EDTA separation solution as previously described5. Protein extracts were prepared using the mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor tablets (Roche). Protein extracts were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%) and transferred to Nitrocellulose Transfer Membrane (Whatman). Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: cleaved caspase-8, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase9 (Cell Signaling), RIP3 (Enzo), Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and secondary HRP-linked anti-Rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling).

Gene expression analyses

Total RNA was extracted from gut tissue or isolated IEC using an RNA isolation Kit (Nucleo Spin RNA II, Macherey Nagel). cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription (iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, Bio Rad) and analyzed by real-time PCR with SsoFast EvaGreen (Bio-Rad) reagent and QuantiTect Primer assays (Qiagen). Experiments were normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene HPRT. For gene chip experiments total RNA of IEC from 3 control and 3 Casp8ΔIEC mice was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and were performed by the Erlangen University core facility using the Affymetrix mouse 430 2.0 chip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). For multiple gene array testing including differential expression analysis the software package FlexArray (http://genomequebec.mcgill.ca/FlexArray) was used. Gene ontology based analyses were performed using the online tool Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID).

Caspase activity

Primary isolated intestinal epithelial cells were cultured with RPMI (Gibco), (10% FCS (PAA), Penicillin (100 U/ml, Gibco), Streptomycin (100 μg/ml, Gibco) in fibronectin (BD Bioscience) coated 48 well plates and caspase-3/-7 activity was measured using the Caspase-Glo3/7 Assay from Promega according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was measured on the microplate reader infinite M200 (Tecan).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student's t-test using Microsoft Excel. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the University Erlangen-Nuremberg and the European Community's 7th Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 202230, acronym GENINCA. E.M. received funding from the Welcome Trust (WT087768MA) and S.M.H. was supported by the NIH Grant AI037988. The authors thank Prof. Alastair Watson (University of East Anglia, UK) for critical reading of the manuscript, Alexei Nikolaev, Stefan Wallmüller, Verena Buchert and Monika Klewer for excellent technical assistance and Jonas Mudter, Raja Atreya and Clemens Neufert for sampling biopsies.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

C.G., K.A., M.F.N. and C.B. designed the research. C.G., E.M., N.W., B.W., H.N., M.W. and S.T. performed the experiments. S.M.H. provided material that made the study possible. C.G., K.A. and C.B. analysed the data and wrote the paper.

Author Informations:

Chip data were deposited at NCBI GEO under the series accession number GSE30873 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE30873). Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors do not have any competing conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117(3):514–521. doi: 10.1172/JCI30587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artis D. Epithelial-cell recognition of commensal bacteria and maintenance of immune homeostasis in the gut. Nature reviews Immunol. 2008;8(6):411–420. doi: 10.1038/nri2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall PA, et al. Regulation of cell number in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract: the importance of apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 12):3569–3577. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nenci A, et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2007;446(7135):557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders DS. Mucosal integrity and barrier function in the pathogenesis of early lesions in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(6):568–572. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elphick DA, Mahida YR. Paneth cells: their role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Gut. 2005;54(12):1802–1809. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.068601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maelfait J, Beyaert R. Non-apoptotic functions of caspase-8. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76(11):1365–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valmiki MG, Ramos JW. Death effector domain-containing proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(5):814–830. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mielgo A, et al. The death effector domains of caspase-8 induce terminal differentiation. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459(7244):262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holler N, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vercammen D, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-induced necrosis versus anti-Fas-induced apoptosis in L929 cells. Cytokine. 1997;9(11):801–808. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenabeele P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(10):700–714. doi: 10.1038/nrm2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137(6):1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Declercq W, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. RIP kinases at the crossroads of cell death and survival. Cell. 2009;138(2):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137(6):1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325(5938):332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser WJ, et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471(7338):368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberst A, et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471(7338):363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4(5):313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wehkamp J, et al. Barrier dysfunction due to distinct defensin deficiencies in small intestinal and colonic Crohn's disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(Suppl 1):S67–74. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewin K. The Paneth cell in disease. Gut. 1969;10(10):804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.10.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arijs I, et al. Mucosal gene expression of antimicrobial peptides in inflammatory bowel disease before and after first infliximab treatment. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayhew TM, et al. Epithelial integrity, cell death and cell loss in mammalian small intestine. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14(1):257–267. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontoyiannis D, et al. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10(3):387–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beisner DR, et al. Cutting edge: innate immunity conferred by B cells is regulated by caspase-8. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):3469–3473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madison BB, et al. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):33275–33283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Marjou F, et al. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis. 2004;39(3):186–193. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker C, et al. In vivo imaging of colitis and colon cancer development in mice using high resolution chromoendoscopy. Gut. 2005;54(7):950–954. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.061283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.