Abstract

Obstacles incurred by RNA polymerase II during primary transcript synthesis have been identified in vivo and in vitro Transcription past these impediments requires SII, an RNA polymerase II-binding protein. SII also activates a nuclease in arrested elongation complexes and this nascent RNA shortening precedes transcriptional readthrough. Here we show that in the presence of SII and nucleotides, transcript cleavage is detected during SII-dependent elongation but not during SII-independent transcription. Thus, under typical transcription conditions, SII is necessary but insufficient to activate RNA cleavage. RNA cleavage could serve to move RNA polymerase II away from the transcriptional impediment and/or permit RNA polymerase II multiple attempts at RNA elongation. By mapping the positions of the 3′-ends of RNAs and the elongation complex on DNA, we demonstrate that upstream movement of RNA polymerase II is not required for limited RNA shortening (seven to nine nucleotides) and reactivation of an arrested complex. Arrested complexes become elongation competent after removal of no more than nine nucleotides from the nascent RNA’s 3′-end. Further cleavage of nascent RNA, however, does result in “backward” translocation of the enzyme. We also show that one round of RNA cleavage is insufficient for full readthrough at an arrest site, consistent with a previously suggested mechanism of SII action.

Gene expression can be controlled by governing the ability of RNA polymerase II to synthesize complete primary transcripts (reviewed in Spencer and Groudine, 1990). Gene sequences have been identified that arrest RNA polymerase II in vivo and in vitro and protein factors that influence RNA elongation have been isolated (reviewed in Kerppola and Kane, 1991); one such factor is elongation factor SII. This protein binds to RNA polymerase II and allows it to transcribe through different types of transcriptional blockages including, DNA-bound protein (Reines and Mote, 1993), DNA-bound drugs,1 and certain template sequences, some of which may attain unusual DNA conformations (Reinberg and Roeder, 1987; Sluder et al., 1989; Bengal et al., 1989; Reines et al., 1989; Izban and Luse, 1992; Wiest et al., 1992; reviewed in Reines, 1993). SII activates nascent RNA cleavage, an activity most probably residing in RNA polymerase II itself (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992, Wang and Hawley, 1993)2,3. Nascent RNA shortening has also been observed in elongation complexes formed with other RNA polymerases including viral and bacterial enzymes (Surratt et al., 1991; Borukhov et al., 1992, 1993; Krummel and Chamberlin, 1992; Hagler and Shuman, 1993). SII activation of nascent RNA cleavage is associated with transcriptional readthrough (Reines et al., 1992; Reines and Mote, 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b). The recent finding that Escherichia coli RNA polymerase’s nuclease activity is also activated by elongation factors (Borukhov et al., 1992, 1993) strengthens the association between RNA cleavage and transcription elongation and demonstrates a conservation between prokaryotic and eukaryotic mechanisms of reactivating arrested transcription elongation complexes. The exact means by which elongation factors and transcript cleavage control transcription elongation are poorly understood.

At least two types of RNA polymerase II elongation complexes have been assembled in vitro: those from which chain elongation occurs in a factor-independent manner and those at which RNA polymerase II needs accessory elongation factors such as SII for efficient chain elongation. Factor-independent complexes have been assembled in vitro by withholding nucleotides or by placing a DNA-binding protein in the path of the enzyme. Provision of the missing nucleotide (Izban and Luse, 1993a, 1993b) or removal of the DNA-bound protein (Reines and Mote, 1993) results in the resumption of chain elongation without the need for added elongation factors. Simply stopping chain elongation is insufficient to make an elongation complex SII-dependent.

RNA polymerase II elongation complexes of the factor-independent or factor-dependent type can be isolated free of nucleotides. In the presence of SII and magnesium, nucleotide-depleted complexes carry out nascent RNA cleavage (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992; Wang and Hawley, 1993). Other RNA polymerase II elongation complexes, including those found at the terminus of a DNA duplex (Reines and Mote, 1993; Wang and Hawley, 1993) and those arrested by incorporating a chain-terminating nucleotide into RNA,1 also carry out SII-activated RNA cleavage. Thus many, if not all, elongation complexes that cannot extend their RNA chains cleave nascent RNA when SII is present. However, in the presence of nucleotides, elongation complexes for which elongation is SII-independent do not appear to cleave their RNA chains even when SII is present in amounts sufficient for readthrough (Reines and Mote, 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b). This suggests that under transcription conditions the inability of an elongation complex to extend an RNA chain is required for nascent RNA cleavage. This distinction may reflect an important difference between SII-dependent and SII-independent complexes.

Recent work has provided additional evidence that SII-dependent and SII-independent elongation complexes are structurally and functionally different (Izban and Luse, 1993b). When depleted of nucleotides, SII-dependent and SII-independent elongation complexes can be activated by SII to cleave their RNA chains. The size of the oligonucleotide removed from the 3′-end of the RNA differs for SII-dependent (7–14 nucleotides) and SII-independent (dinucleotide) complexes (Izban and Luse, 1993a, 1993b). By constructing template variants with extended tracts of A residues on the template strand, an elongation competent complex was converted, in part, into an elongation-incompetent complex (Izban and Luse, 1993b). Concomitant with the acquisition of SII dependence for efficient elongation, these complexes, when nucleotide depleted, now remove large fragments from nascent RNA, the increment characteristic of elongation-incompetent complexes. Thus, there is a correlation between the elongation competence of a complex and the step-size of nascent RNA cleavage. E. coli elongation complexes also display two modes of nascent RNA cleavage (Surratt et al., 1991; Borukhov et al., 1993). The large cleavage increment is activated by one factor and the small increment by a separate gene product (Borukhov et al., 1993). One of these factors, greA, has independently been implicated in transcription elongation (Sparkowski and Das, 1992), strengthening the idea that cleavage is causally related to transcriptional read-through.

Some intrinsic transcription blockages arrest RNA polymerase II in the presence of a full complement of nucleotides. Such sites are probably involved in controlling transcription elongation in vivo (Kerppola and Kane, 1991). Arrested complexes display SII-activated transcript cleavage even in the presence of high levels of nucleotides. Although RNA cleavage is an intermediate in, and perhaps causally related to, SII-mediated elongation (Reines, 1992; Reines et al., 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992,1993b), the mechanism by which RNA cleavage potentiates subsequent chain elongation is not known. Transcript cleavage may facilitate readthrough by altering the relationship of the polymerization catalytic site to the 3′-hydroxyl of the RNA terminus (Borukhov et al., 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b). It may also provide RNA polymerase II multiple opportunities to transcribe through an arrest site (Reines, 1992). One possibility is that the enzyme translocates upstream (“backwards”) as a result of cleavage (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992; Richardson, 1993, Kassavetis and Geidushek, 1993; Wang and Hawley, 1993). This could result in a change in the template’s conformation. A physical rearrangement of nucleic acid and protein could be important for transcriptional readthrough. There is, however, little structural information concerning arrested or SII-activated elongation complexes.

In this report we provide evidence that SII-independent elongation complexes do not cleave their nascent RNA chains under typical transcription conditions. Under the same conditions, complexes arrested at a naturally occurring arrest site carry out RNA cleavage during SII-activated elongation. No more than nine nucleotides are removed from the 3′-end before the arrested complex is reactivated for elongation. Using exonuclease III as a probe, we have defined the boundaries of arrested elongation complexes and complexes that have cleaved or extended their RNAs. Instead of translocating upstream, these boundaries move slightly downstream after as many as nine nucleotides are removed from the nascent RNA. This indicates that SII rescue of arrested RNA polymerase II does not require upstream translocation of the complex along the template. We also present evidence supporting the idea that multiple iterations of cleavage and resynthesis are employed to achieve high levels of readthrough by RNA polymerase II.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and Reagents

RNA polymerase II and general transcription initiation factors were isolated from rat liver as described (Conaway et al., 1987; Reines, 1991). Recombinant α was purified from E. coli as described (Tsuboi et al., 1992). SII was partially purified from rat liver or bovine brain as described (Reines, 1991).

Exonuclease III and formalin-fixed Staphylococcus aureus (Immunoprecipitin) were obtained from Bethesda Research Laboratories-Life Technologies. Fast protein liquid chromatography-purified NTPs,4 ddNTPs, and 3′-O-methyl GTP were purchased from Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology Inc., 3′-dUTP was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. [α-32P]CTP and [γ-32P]ATP were purchased from Amersham Corp.

Plasmids and Templates

The plasmid pAdTerm-2 was derived from pDNAdML by inserting a segment of the human histone H3.3 gene into its AccI site (Reines et al., 1989). pDNAdML contains the adenovirus major later promoter (−50 to +10) inserted into pUC18 at the KpnI and XbaI sites (Conaway and Conaway, 1988). Where indicated, template DNA was labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase to a specific activity of ≈2–4 × 106 counts/min/pmol after digestion with PstI (to label the template strand) or EcoRI (non-template strand) and phosphatase treatment. Labeled DNA was digested with PvuII and the resulting, uniquely end-labeled fragments (545 bp for PstI-labeled DNA, 481 bp for EcoRI-labeled DNA) were purified from a 5% (acrylamide/bisacrylamide, 19:1 (w/v)) non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel for use as transcription templates.

Elongation Complex Synthesis

In vitro transcription was reconstituted with partially purified initiation factors and RNA polymerase II as described (Conaway et al., 1987). A single reaction contained NdeI-cut pAdTerm-2 (50 ng) (for exonuclease mapping: ≈5 ng (40,000 counts/min) of 32P-labeled template and 45 ng of poly(dG-dC)-poly(dG-dC) (Pharmacia)), RNA polymerase II (0.5 μg) and fraction D (2 μg) in 20 μl of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 2.2% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol, 12 units RNAguard (Pharmacia), 0.5 mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin (New England BioLabs), 150 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 3% (v/v) glycerol. After 30 min at 28 °C, 33 μl of a solution containing fraction B′ (1 μg) and recombinant α in the same buffer without KCl were added and incubation continued for another 20 min. MgCl2, ATP, UTP (7 mM, 20 μM, and 20 μM, respectively) and [α-32P]CTP (>400 Ci/mmol, ≈0.6 μM) or unlabeled CTP (20 μM) were added for 20 min more. An initiated complex containing a 14-base transcript was synthesized since the first G appears in the transcript at position +15. To generate arrested complexes, initiated complexes were made 10 μg/ml in heparin and 800 μM in each NTP and incubated for 15 min at 28 °C, Complexes were immunoprecipitated by incubation with 0.8 μg of D44 IgG (Eilat et al., 1982; Reines, 1991) for 10 min on ice. Ten μl of fixed S. aureus washed in reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 3 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.9, 60 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.3 mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin, 2.2% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol, 3% (v/v) glycerol) were added for an additional 10 min. Complexes were collected by centrifugation for 2 min in a microcentrifuge and washed three times with 1.5 volumes of reaction buffer. These washed complexes were resuspended in 60 μl of reaction buffer for further treatment. RNA cleavage was activated by the addition of 0.5–2 μg of phosphocellulose purified bovine brain SII (unless otherwise indicated) and MgCl2 (7 mM) and incubated at 28 °C for the indicated times.

Exonuclease III Mapping

Washed complexes arrested at site Ia or treated with SII in the presence or absence of nucleotides were incubated with 7 mM MgCl2 and 65 units (1 unit releases 1 nmol of mononucleotide from sonicated DNA in 30 min at 37 °C) of exonuclease III in reaction buffer at 37 °C for 3 min. Mock digestions did not receive exo III during the incubation. For the investigation of the upstream boundaries of elongation complexes, washed complexes were digested with HindIII at 37 °C for 10 min in reaction buffer containing 7 mM MgCl2 prior to SII addition and exo III treatment. Mock digestions did not receive HindIII during this incubation. All reactions were terminated by addition of an equal volume of SDS-containing buffer (Reines, 1992) and digestion with proteinase K. Nucleic acids were ethanol precipitated and dried.

Electrophoresis and Autoradiography

Nucleic acids were dissolved in 80% (v/v) formamide, 0.025% (w/v) xylene cyanol, and 0.025% (w/v) bromphenol blue in TBE (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, pH 8.0,1 mM EDTA). Nucleic acids were resolved on 5% (w/v) (15% for Fig. 1, A and B) polyacrylamide gels (19:1, acrylamide/bisacrylamide), in TBE and 8.3 M urea. Gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film (Kodak XAR or Amersham Hyperfilm-MP) in the presence or absence of an enhancing screen (Dupont).

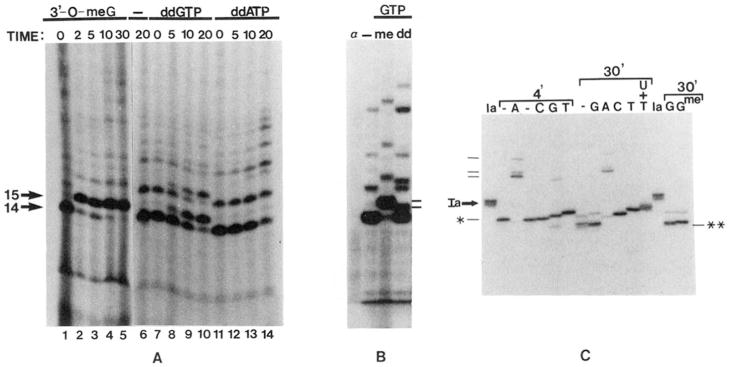

Fig. 1.

A, incorporation of chain-terminating nucleotides into RNA. Initiated complexes were synthesized using pDNAdML as a template. 3′-O-Methyl GTP (1.4 mM, lanes 1–5), water (lane 6), ddGTP (150 μ;M, lanes 7–10), or ddATP (150 pM, lanes 11–14) were added and incubated at 28 °C for the indicated times. B, mobility of RNA chains containing chain terminators. H20 (–), 3′-O-methyl GTP {me, 420 μM), or ddGTP (dd, 170 μM) were incubated with initiated complexes assembled on pDNAdML for 10 min at 28 °C. One reaction (α) received α-amanitin (1 μg/ml) before any nucleotides. The 15-base, ddGMP-containing RNA (lower dash) and that containing 3′-O-methyl GMP are indicated to the right. C, extension of cleaved RNA chains by dideoxynucleotides. Washed elongation complexes arrested at site Ia (lanes Ia) were incubated for 4 or 30 min with SII (rat liver, 140 ng HAP fraction) and 7 mM MgCl2 to generate the first (*) or second (**) cleavage products, respectively. Samples were stopped (lanes –) or incubated with the indicated dideoxynucleotide (G, C, A, or T, 160 μM each) and the other three ribonucleotides (400 μM each) for 15 min at 28 °C. For comparison, one sample received 3′-O-methyl GTP (160 μM) instead of ddGTP. One reaction contained UTP (2 μM, U+T) in addition to ATP, CTP, GTP, and ddTTP to obtain chains terminated at downstream template A residues. *, A198-RNA; **, G196-RNA, dashes at left indicate RNAs terminating at positions 218, 220, and 226 (bottom to top)

RESULTS

Mapping of the Major Cleavage Products Produced by an Arrested RNA Polymerase II Elongation Complex

A particular site within a human histone gene, termed site Ia, has served as a valuable model for analysis of factor-dependent transcription elongation. In vitro, 40–50% of the RNA polymerase II molecules cannot bypass site Ia in the absence of elongation factor SII. In the presence of SII, however, the arrested enzyme efficiently reads through this site (Reines et al., 1987, 1989, 1992). This process involves activation by SII of a nascent RNA cleavage reaction (Reines et al., 1992; Izban and Luse, 1993b).

A time course of RNA cleavage by nucleotide-depleted, arrested elongation complexes showed that there were preferred sites to which RNA chains were shortened (Reines, 1992; Reines et al., 1992). To map the 3′-end of the major cleavage products, we wanted to exploit the ability of arrested RNA polymerase II to carry out limited chain elongation with chain-terminating nucleotide derivatives. In this manner we could “sequence” the template region surrounding arrested RNA polymerase II similar to the dideoxynucleotide sequencing strategy described for DNA polymerases (Sanger et al., 1977). First, we needed to show that rat liver RNA polymerase II could incorporate chain-terminating analogues into RNA. Transcription was initiated from the adenovirus major late promoter using partially purified rat liver RNA polymerase II and general initiation factors (Conaway et al., 1987; Reines et al., 1989). In the presence of either 3′-O-methyl GTP or ddGTP, a 14-nucleotide transcript lacking guanosines was extended by a single residue, confirming that both chain terminators serve as substrates for RNA polymerase II (Fig. 1A). The 3′-O-methyl derivative was a more efficient substrate than the dideoxy derivative,5 The commercial availability of the dideoxy derivatives containing all four bases made these the preferred chain terminator for this application. Incorporation of ddGTP was template dependent and base specific since ddATP was not used as a substrate at this position (Fig. 1A). Chains containing the dideoxy nucleotide have a higher electrophoretic mobility on denaturing-polyacrylamide gels than those ending in 2′-hydroxyl and 3′-O-methyl groups or 2′- and 3′-hydroxyl groups (Fig. 1B).

Elongation complexes arrested at site Ia were assembled and washed free of nucleotides by immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody against RNA (Eilat et al., 1982; Reines, 1992). RNA cleavage was carried out by adding SII and MgCl2 to the washed complexes and incubating them for 4 or 30 min at 28 °C. Two different cleavage intermediates (Fig. 1C, indicated by * and **) were generated in this manner. Each cleaved RNA was then extended in four separate reactions in the presence of either ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP and the other three ribonucleoside triphosphates. Cleaved RNAs were extended up to and including the position of the first template A, G, C, or T residue after the cleavage site (Fig. 1C). These chain-terminated RNAs were separated by size and compared to the sizes of unextended cleavage products and uncleaved transcript Ia. The resulting “ladders” enabled us to determine nucleotide sequence between the cleavage products and site Ia. From the known DNA sequence of this region (Reines et al., 1987), we could infer the positions of the various RNA termini. Taking into account the mobility differences (Fig. 1, B and C, compare ddGTP lane with 3′-O-methyl GTP lane) between RNAs bearing dideoxy and 2′, 3′-hydroxyl groups, the 3′-ends of these intermediates mapped to positions A198 and G196 (* and **, respectively; Fig. 5, B and C). (All position numbering in this paper will be indexed to the transcription start site, +1.) When indexed using the chain-terminated RNAs (Fig. 1C, lanes G, A, C, T, and U+T), uncleaved Ia RNAs appeared as a family of transcripts with 3′ termini at positions 205, 206, and 207 (Fig. 1C, lanes Ia). This differs slightly from the previous placement of these ends at positions 202, 203, 204, and 205 by S1-nuclease mapping experiments (Reines et al., 1987). This difference could be due to “breathing” of the long poly(rU)-poly(dA) region of the hybrid during S1 digestion. The determination of 3′ termini presented here is more direct, and these map positions will be used henceforth. Kinetic analysis has shown that the 198-nucleotide RNA is generated first from Ia-RNA, and it serves as a precursor to the formation of the 196-nucleotide RNA (Reines, 1992). Hence, under these conditions the three Ia-RNA chains (205,206, and 207 nucleotides) are rapidly (<1 min; Reines, 1992, and Fig. 6A, this work) shortened by seven to nine nucleotides to a single product (A138). This RNA is subsequently shortened by two additional nucleotides to the 196-base RNA (**) which persists for approximately 1 h under typical cleavage conditions (Reines, 1992).

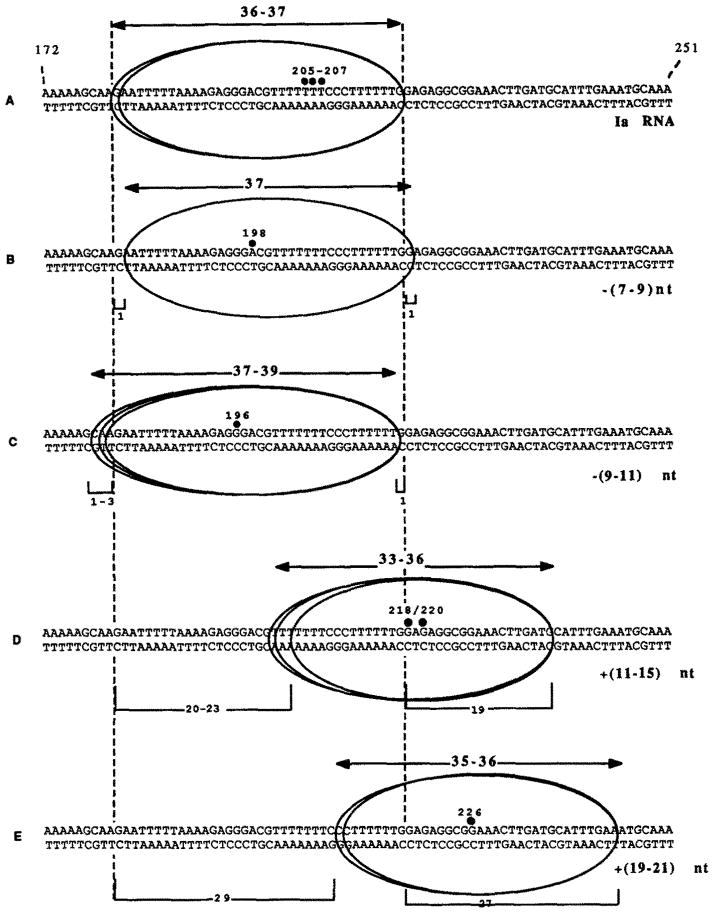

Fig. 5. Schematic summary of exonuclease III protection experiments.

The upstream and downstream boundaries are displayed along a portion of the template (+172 → +251) for five elongation complexes: A, the complex arrested at site Ia; B, the complex bearing the first cleavage intermediate (*, A198); C, the complex bearing the second cleavage intermediate (**, G196); D, the complex containing RNAs extended to G218 and G2M; and E, the complex containing RNAs extended to G226, Numbered, filled circles depict the positions of RNA 3′-ends, bidirectional arrows show minimum-maximum boundary distances for each complex, vertical dashed lines show boundary positions for complex Ia, numbers in parentheses to the right show number of nucleotides removed (−) or added (+) to transcripts Ia, and numbered brackets show position differences between a boundary (upstream or downstream) determined for complex Ia and that complex.

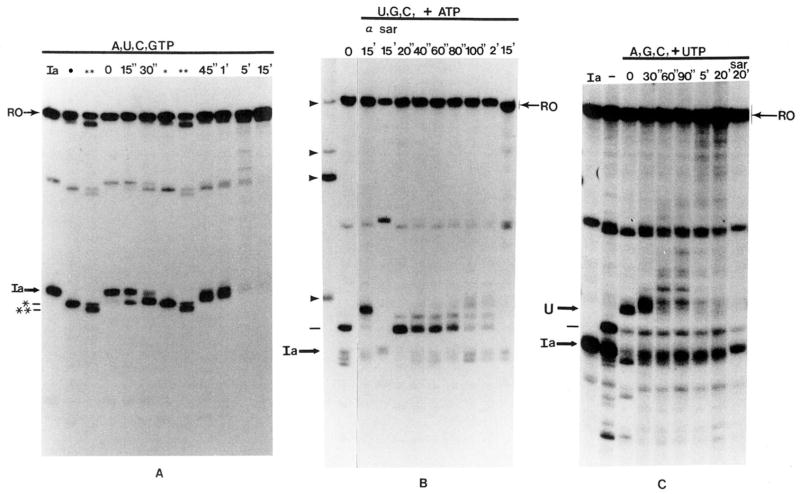

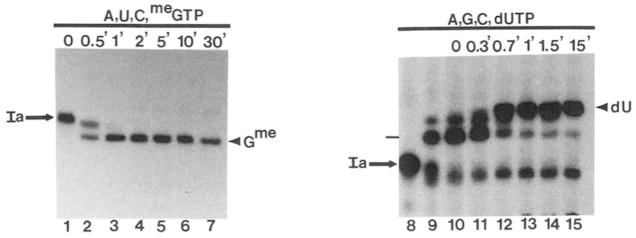

Fig. 6.

A, time course of SII-dependent elongation from site Ia in the presence of all four nucleotides. Washed complexes (lane Ia) were split into 2 aliquots. One received bovine brain SII and 7 mM MgCl2 and was incubated at 28 °C for 1.5 or 15 min to generate the first (*) and second (**) cleavage intermediates, respectively. The second aliquot of washed complexes received bovine brain SII, MgCl2, and 800 μM each of all four NTPs. Portions of this reaction were stopped after the indicated times at 28 °C and analyzed by electrophoresis with the first and second cleavage intermediates. RO, runoff RNA. B, RNA elongation by an SII-independent elongation complex in the presence of SII. RNA in washed complexes was extended for 10 min at 28 °C to positions G218/G220 (indicated by dash at left, lane 0) in the presence of UTP, CTP, and GTP (800 μM each), bovine brain SII, and 7 mM MgCl2. The reaction was chilled to 4 °C, ATP (800 μM) was added, and samples were stopped at the indicated times after incubation at 28 °C. One sample (sar) was adjusted to 0.25% in Sarkosyl and another (α) to 1 μg/ml in α-amanitin before the addition of ATP and incubation at 28 °C. Arrowheads indicate the position of marker RNAs of 260, 380, 420, and 540 nucleotides (bottom to top). C, RNA elongation by a second SII-independent elongation complex in the presence of SII. Elongation complexes were assembled at site Ia (Ia) and moved to positions G218/G220 (dash to left of figure) as described in the legend to B. These complexes were washed free of nucleotides by centrifugation and resuspension and moved to position C230 (U) after an 8-min incubation at 28 °C in the presence of bovine brain SII, 7 mM MgCl2, and 800 μM each of ATP, GTP, and CTP. The reaction was incubated at 28 °C with UTP (800 μM) for the indicated times. One sample (sar) was made 0.25% in Sarkosyl before the addition of UTP and incubation at 28 °C.

Exonuclease III Mapping of RNA Polymerase II Elongation Complexes after RNA Cleavage and Extension

We were interested in determining whether the contacts between RNA polymerase II and template DNA changed after RNA cleavage. To determine the downstream boundary, arrested complexes were assembled on linear templates labeled with 32P at the 5′-end of the non-template strand. Elongation complexes arrested at site Ia were immunoprecipitated with anti-RNA IgG. RNA synthesis was verified by labeling transcripts with [α-32P]CTP (Fig. 2B, lanes 1–5 and 11–13). Identical complexes bearing unlabeled transcripts were digested with exonuclease III, an enzyme which cleaves DNA specifically from its 3′-end. The exo III assay is depicted schematically in Fig, 2A. Complexes arrested at site Ia yielded a single prominent exo III product at position G217 on the non-template strand (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 14), 11 bp downstream from the center of the T cluster that defines site Ia (Fig. 5A). Templates on which complex-assembly was prevented by including α-amanitin prior to nucleotide addition (Fig. 2B, lane 1) were digested to completion by exo III (Fig. 2B, lane 6). RNA was quantitatively precipitated from these reactions while <10% of the input DNA co-precipitated.6 This is consistent with the low level of template occupancy noted for these reactions (Conaway et al., 1987; Reines, 1991); however, some labeled template was also precipitated from reactions in which RNA synthesis was prevented by the inclusion of α-amanitin. The amount of this DNA was variable but less than that obtained from amanitin-lacking reactions (Fig. 2B, lane 1 versus lane 2; Fig. 4, lane 22 versus lane 23). Since DNA is present at a much higher concentration than RNA, cross-reactivity of the antibody with DNA (Eilat et al., 1984; Reines, 1991) could account for this observation. In any case, the complex-free template precipitated in amanitin-containing reactions served as an internal control demonstrating the specificity of the exo III protections observed.

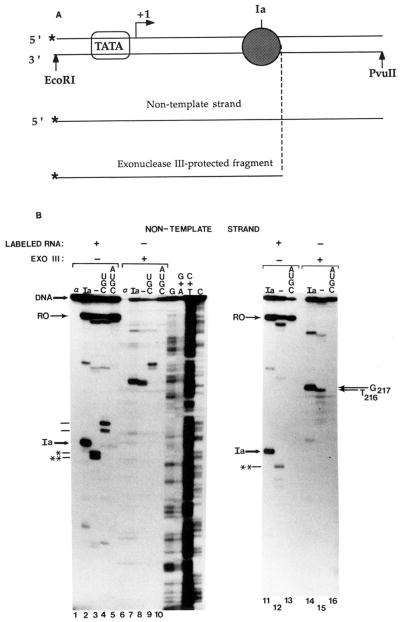

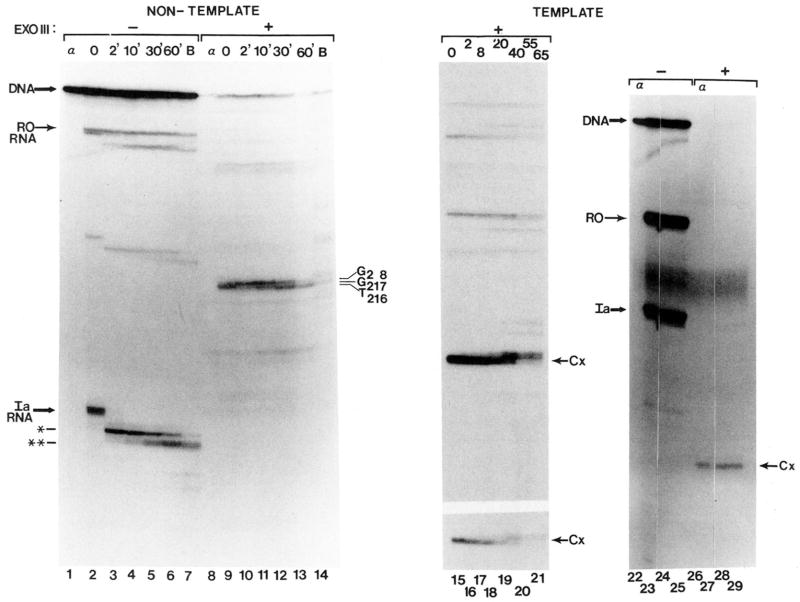

Fig. 2. Exonuclease III mapping of the downstream boundaries of elongation complexes.

A, schematic representation of exo III assay of arrested elongation complexes (dark sphere) at site Ia on labeled (*) non-template strand. Bent arrow indicates transcription start site. B, washed complexes arrested at site Ia (Ia) bearing 32P-labeled or unlabeled RNA (as indicated) were assembled on a DNA fragment labeled at the 5′-end of the non-template strand (see “Materials and Methods”). RNA cleavage (lanes 3,8,12, and 15) or elongation (lanes 4, 5, 9, 10, 13, and 16) was carried out by providing bovine brain (lanes 3 and 8) or rat liver (2.4 μg of phosphocellulose fraction) SII, 7 mM MgCl2 and either no nucleotides (–), UTP, CTP, and GTP (UGC) or all four ribonucleotides (AUGC). Complexes were mock treated or digested with exo III as indicated. When present, α-amanitin (1 μg/ml, lanes 1 and 6) was added prior to synthesis of initiated complexes. The major cleavage products are indicated by * and **. RNAs extended to positions G218/220 (lower) and G226 are indicated with dashes to the left. Full-length template strand (DNA) and DNA fragments protected from exo III (G217, 7*16) are indicated. G, G+A, C+T, C, chemical cleavage (Maxam and Gilbert, 1980) at the respective bases of 32P-template DNA; RO, runoff RNA.

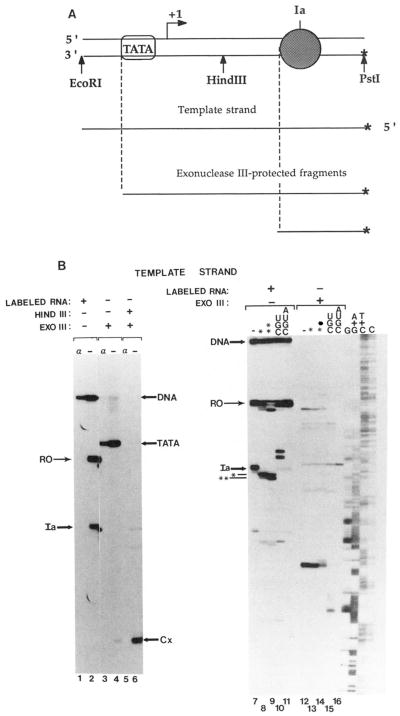

Fig. 4. Time course of elongation complex boundary movement.

Washed complexes containing labeled (lanes 1–7 and 22–25) or unlabeled RNA (lanes 8–21) were prepared on DNA labeled at the 5′-end of either the non-template (lanes 1–14) or template (lanes 15–29) strands. Complexes were HindIII (lanes 15–21 and 26–29) or mock (lanes 22–25) digested and incubated with SII (180-ng rat liver HAP fraction, lanes 15–20; 240 ng, lane 21; 1 μl of TSK-Φ fraction, lanes 2–6 and 9–13; bovine brain phosphocellulose fraction, lanes 7 and 14) and 7 mM MgCl2. After the indicated time at 28 °C (or 20 min, lanes 22–29) samples were mock or exo III digested as indicated. Control reactions received α-amanitin (lanes α 1 μg/ml) from the start and were stopped before incubation with SII. Some washed complexes at site Ia were incubated with α-amanitin for 20 min at 28 °C before exo III digestion (1 μg/ml, lanes 24, 25, 28, and 29) with (lanes 25 and 29) or without (lanes 24 and 28) SII (60-ng rat liver HAP fraction). DNA fragments protected from exo III digestion are indicated to the right of each panel. The lower panel in lanes 15–21 shows a shorter exposure of the region of the gel containing the exo III protection products.

Complexes arrested at site Ia were incubated with partially purified SII to activate RNA cleavage. Ia-RNA was cleaved to approximately equal amounts (Fig. 2B, lane 3) of the two major products characterized above as the 196- and 198-nucleotide transcripts. After treatment of these complexes with exo III (Fig. 2B, lane 8), a fragment with a 3′-end at position T216 was seen in addition to the exo III product at G217 (Fig. 2B, lane 7). Further RNA cleavage resulted in the loss of the 198-nucleotide RNA (Fig. 2B, lane 12). The major product was the RNA with a 3′-end at G196. Small amounts of shorter transcripts were also observed. After exo III treatment, the T216 fragment was seen along with fragments ending at T214 and T212 (Fig. 2B, lane 15). Protection from exo III was no longer found at position 217. These results suggest that, shortening of the transcript by seven to nine nucleotides (*, Fig. 2B, lane 3) resulted in no change in the elongation complex’s downstream boundary, but after an additional two nucleotides were removed from the first intermediate (**, Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 12), the relative position of this boundary on DNA was displaced upstream by a single base pair. Hence, after more extensive RNA shortening we were able to detect the upstream movement of the elongation complex. These mapping data are summarized in Fig. 5, A–C.

To examine the movement of RNA polymerase II after RNA chain elongation, GTP, CTP, and UTP were added with SII to nucleotide-depleted complexes arrested at site Ia. This resulted in limited extension of Ia-RNA by 11–15 nucleotides to G218 and G220 with some readthrough to the next position where ATP is required, G226 (Fig. 1C, lane 3; Fig. 5D). Exo III treatment of these ATP-starved complexes yielded DNA fragments protected from digestion at G236 and A244 (Fig. 2B, lane 9).5 Hence, lengthening of transcript Ia by 11–15 nucleotides resulted in a downstream displacement of the downstream boundary by 19 bases to position 236. Extension of the RNA to 226 nucleotides (the addition of 19–21 nucleotides) is accompanied by movement of the elongation complex’s downstream boundary by 27 bases. All exo III protection was lost when arrested complexes were permitted to move to the end of the template in the presence of all four nucleotides (Fig. 2B, lanes 5, 10, 13, and 16).

To identify the upstream boundary of these elongation complexes, an identical experiment was performed with the duplex labeled at the 5′-end of the template strand (Fig. 3A). In this case, exo III shortening of the template strand was monitored as the nuclease approached the elongation complex from the upstream terminus of the duplex (Fig. 3A). Exo III treatment of complexes arrested at site Ia resulted in an unexpectedly large protected fragment terminating upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). The size of this protected fragment, and its resistance to an α-amanitin treatment that abolished transcription (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 3), suggested that the binding site of components of the transcription initiation complex, perhaps TATA-binding protein(s), had been identified. This was confirmed in exo III mapping experiments where labeled DNA was incubated with only yeast TATA-binding protein purified from E. coli.6 This finding is consistent with other experiments suggesting that TATA-box-associated factors remain bound to the adenovirus major late promoter after chain initiation and departure of the enzyme from the promoter region (van Dyke et al., 1988, 1989). In our experiments, the complexes were immunoprecipitated and extensively washed, demonstrating the extreme stability of this nucleoprotein complex. The TATA-binding protein is known to dissociate slowly from this binding site in a solution containing 60 mM KCl (t1/2≈ 1 h; Hoopes et al., 1992).

Fig. 3. Exonuclease III mapping of the upstream boundaries of elongation complexes.

A, schematic representation of exo III assay of arrested elongation complexes at site Ia on labeled (*) template strand. Encircled TATA indicates TATA-box sequence and associated binding protein(s). Other symbols are as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2A. B, washed complexes arrested at site Ia bearing 32P-labeled or unlabeled RNA were assembled on a DNA fragment 32P-labeled at the 5′-end of the template strand (see “Materials and Methods”). RNA cleavage (lanes 8, 9,13, and 14) or chain extension (lanes 10, 11, 15, and 16) were carried out by adding SII (rat liver, 140 ng; HAP fraction), 7 mM MgCl2, and either no nucleotides (–) or UTP, GTP, and CTP (UGC) or all four ribonucleotides (AUGC) and incubating for 4 (lanes 8 and 13) or 15 (lanes 9–11 and 14–16) min at 28 °C. Complexes were either treated with HindIII (lanes 5–16) or mock treated (lanes 1–4) and then digested with exo III (lanes 3–6 and 12–16) or mock-treated (lanes 1, 2, and 7–11). When present, α-amanitin (1 μg/ml, lanes 1, 3, and 5) was added prior to RNA synthesis. Chemical cleavage of 32P-template DNA at the respective bases is shown in lanes G, A+G, T+C, and C. The positions of DNA template and RNA are indicated as de in the legend to Fig. 2. The DNA fragment protected from exo III by TATA-binding proteins (TATA) and complexes arrested at site Ia (Cx) are indicated.

A small amount of a shorter template fragment was also apparent in these exo III digests (Fig. 3B, lane 4, Cx), suggesting that exo III molecules that traveled passed the TATA-box region had detected elongation complexes arrested at site Ia. The blockage of exo HI by factors bound at the TATA region hindered identification of the upstream boundary of arrested elongation complexes. To remove this obstacle, we used the restriction enzyme HindIII to cleave the labeled template into two pieces; the promoter region with TATA-bound factors and the label-containing DNA with elongation complexes (Fig. 3A). Exo III digestion from this new HindIII-generated terminus revealed protected fragments ending mostly at position 181 with some signal at position 182 (Fig. 3B, lanes 6 and 12). This exo III product was absent when RNA synthesis was prevented with α-amanitin (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 5). After cleavage of Ia-RNA to predominantly the 198 nucleotide RNA (*, Fig. 3B, lane 8), the exo III protection was maintained at positions 181 and 182 with a shift in the ratio of the bands toward the smaller (182) of the two fragments (Fig. 3B, lane 13 and Fig. 4, lanes 15–17). Cleavage of transcript Ia to predominantly the second intermediate (**, Fig. 3B, lane 9) resulted in an upstream shift in exo III protection by 1–3 bp (lane 14). Extension of RNAs to G218, G220, and G226 (Fig. 3B, lane 10) resulted in protection of the template strand to positions A201/A202, A204, and G209/G210 (lane 15). The addition of all four nucleotides resulted in extension of all chains to runoff length (Fig. 3B, lane 11) and loss of all exo III protection (lane 16). These results are summarized in Fig. 5.

Taken together, the mapping of the upstream and downstream boundaries of the elongation complex revealed that shortening of nascent RNA by 7–9 bases was not accompanied by upstream movement of the elongation complex (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). Indeed, a small but reproducible forward movement of the elongation complex’s boundaries was detected (Fig. 5B). Only when the second intermediate was generated, representing a loss of 9–11 nucleotides from transcript Ia, was an upstream shift of exo III boundaries detected. The size of the exonuclease footprint (boundary-to-boundary distance) did not change significantly after chain cleavage (≈37 bp, Fig. 5, B and C). After extension of Ia RNA by 11–15 G218/ G220) or 19–21 bases (to G226), the exo III boundaries translocated downstream. The interboundary distances appeared slightly smaller for these complexes, 33–36 and 35–36 bp, respectively.

To study further the possibility that cleavage of transcript Ia to the first intermediate might not be accompanied by any upstream movement of the elongation complex along DNA, we examined the time course of transcript cleavage by high resolution polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4, lanes 1–7). Elongation complexes were sampled during the course of cleavage and treated with exo III to determine at what point during cleavage the downstream (Fig. 4, lanes 8–14) and upstream (Fig. 4, lanes 15–21) boundaries translocated. This analysis revealed that the downstream boundary advanced downstream by one base pair (to G218; lanes 10 and 11) concomitant with shortening of transcript Ia to the first intermediate. Only after nascent RNA was shortened to 196 nucleotides, did this boundary move upstream (Fig. 4, lanes 5–7 and 12–14). The upstream boundary showed a similar downstream movement (Fig. 4, lanes 15–18) during the time in which the first cleavage product was quantitatively generated from transcript Ia. Again, only after the first cleavage product (A198, *) was converted into the second (G196, **) did the complex’s boundary move significantly upstream (Fig. 4, lanes 5–7 and 19–21). α-Amanitin inhibits RNA cleavage (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992; Wang and Hawley, 1993; Fig. 4, lane 25, this work). Neither α-amanitin alone, nor α-amanitin and SII together, resulted in a change in the upstream boundary of elongation complexes (Fig. 4, lanes 28 and 29).

Transcript Cleavage Accompanies Elongation by SII-dependent Elongation Complexes But Not SH-independent Complexes

Kinetic analysis of RNA extension through site Ia, where elongation is SII dependent, shows that RNA cleavage precedes chain elongation (Reines et al., 1992; and Fig. 6A, this work). If transcript cleavage is causally involved in SII-activated elongation, cleavage might not take place during SII-independent transcription in the presence of SII. To test this idea, we prepared arrested elongation complexes halted downstream from site Ia by permitting only limited elongation from site Ia in the absence of ATP. This resulted in RNA polymerase II halted predominantly at G218/220/226 (Reines et al., 1992; Figs. 1C and 6B). Chain elongation through this site does not require SII. After ATP was added, and in the presence of SII, RNA polymerase II readily extended the RNA chain with no evidence of shortened intermediates of the kind seen during elongation through site Ia (compare Fig. 6, A with B). Extension of this RNA was resistant to Sarkosyl as expected for SII-independent elongation (Fig. 6B, sar). These findings confirm and extend earlier work demonstrating that under transcription conditions, i.e. in the presence of a high concentration of nucleotides, SII is necessary but not sufficient for RNA cleavage, at least at levels of SII that support readthrough (Reines and Mote, 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b). Note as well, that in the presence of all four nucleotides, cleavage by the complex arrested at site Ia does not proceed past the first cleavage intermediate defined for the nucleotide-depleted complexes (*, Fig. 6A). This suggests that in the presence of nucleotides, cleavage need not extend further than this point (G198) before RNA polymerase II can resume chain elongation.

Another SII-independent, halted elongation complex was synthesized by depleting complexes arrested at G218/220/226 of nucleotides (Fig. 6C, –) and supplying them with CTP, GTP, and ATP. RNA polymerase II now becomes halted at C230 due to the lack of UTP (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6C, lane 0). After the addition of UTP and SII, elongation from this site in the presence of SII again failed to reveal shortened RNA intermediates (Fig. 6C). Chain extension from this site is also resistant to Sarkosyl (Fig. 6C, lane sar). Thus, RNA polymerase II halted by nucleotide starvation at two sites at which elongation is SII independent did not display RNA cleavage in the presence of SII under conditions where cleavage is readily detected during SII-dependent elongation.

To exclude the possibility that chain shortening occurred but was not detected because cleaved RNA was short-lived, we added the chain-terminating analog 3′-dUTP along with SII, ATP, CTP, and GTP to washed elongation complexes arrested at G218/220/226. If RNA chains were cleaved by two or more residues, the incorporation of a chain terminator would trap the shortened product as seen for SII-dependent elongation from site Ia (Reines et al., 1992; Fig. 5 and Fig. 7, lanes 1–7). Instead, we observed only extension of the RNA before chains were terminated with 3′-dUMP (Fig. 7, lanes 8–15), consistent with direct elongation of the chain from this site without proceeding through an intermediate shortened by more than two nucleotides. Similar results were obtained when 3′-O-methyl GTP was substituted for GTP during elongation.5 Incorporation of 3′-O-methyl GMP would trap an RNA intermediate shortened by one or more nucleotides (Fig. 5). Therefore, RNA cleavage can be detected readily during SIIS-mediated elongation but is not observed under these conditions during SII-independent transcription.

Fig. 7. Time course of RNA elongation by SII-dependent (lanes 1–7) and SII-independent (lanes 9–15) elongation complexes in the presence of a chain-terminating nucleotide.

Washed complexes arrested at site Ia (Ia) were prepared (lanes 1 and 8). Bovine brain SII, MgCl2 (7 mM), ATP, UTP, CTP (800 μM each), and 3′-O-methyl GTP (830 μM, lanes 1–7) were added, and samples were stopped after the indicated times at 28 °C. In lanes 9–15, complexes arrested at site Ia were first moved to G218/G220 as described in the legend to Fig. 6B. These complexes were washed and provided with SII, MgCl2 (7 mM), ATP, GTP, CTP (800 μM each), and 3′-dUTP (800 μM). After the indicated periods of time at 28 °C, samples were stopped and analyzed by electrophoresis. RNAs terminated with 3′-O-methyl GMP and 3′-dUMP are indicated with arrowheads.

As a control experiment, we tested whether chain elongation by complexes arrested at G218/220 was possible in the presence of α-amanitin. To our surprise, in the presence of a concentration of α -amanitin that completely inhibits 1) the synthesis of a 14-nucleotide RNA (Fig. 1B), 2) the synthesis of transcript Ia, 3) the synthesis of runoff RNA (Figs. 2–4, lanes 1), and 4) RNA cleavage at site Ia (Fig. 4, lane 25), RNA chains were extended significantly (≈8 residues; Fig. 6B, lane α) by RNA polymerase II halted at G218/220. This demonstrated that more than one phosphodiester bond can be assembled in the presence of this RNA polymerase-binding toxin.

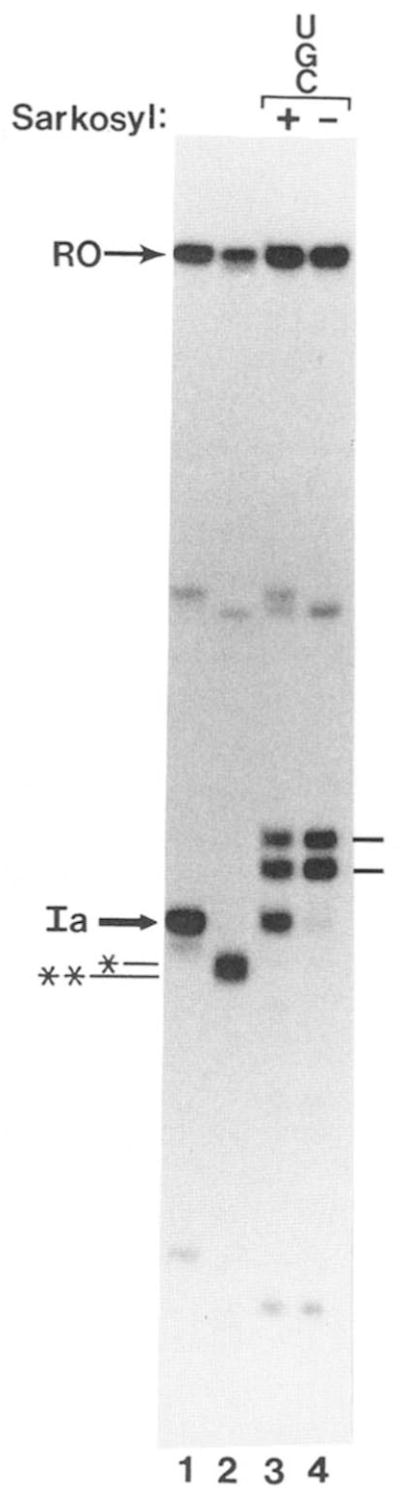

One Cycle of Transcript Cleavage and Re-extension Is Insufficient for Some Polymerases to Read Through Site Ia

The anionic detergent Sarkosyl inhibits SII-activated chain elongation (Reines et al., 1989) and SII-activated nascent RNA cleavage (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992) but does not alter SII-independent chain elongation (Gariglio et al., 1974; Reines et al., 1989). If SII-activated transcript cleavage is sufficient to immunize an elongation complex to the arresting features of site Ia, then the resumption of elongation after RNA shortening should be Sarkosyl-resistant. To test this idea we allowed washed elongation complexes arrested at site Ia to cleave their transcripts quantitatively (Fig. 8, lane 2). Reactions were challenged with Sarkosyl and a restricted set of nucleotides (UTP, GTP, and CTP) for 30 min. Read-through of site Ia was monitored by accumulation of RNA polymerase II at G218/220 and G226. Compared to control reactions where readthrough proceeds quantitatively in the absence of detergent (Fig. 8, lane 4), Sarkosyl prevented read-through of site Ia by 57 ± 9% (mean ± standard deviation, n = 7; as determined by video densitometry) of the RNA polymerase molecules (Fig. 8, lane 3). This is similar to the proportion of enzyme molecules that fail to readthrough site Ia upon their first encounter with it (Reines et al., 1989; Fig. 8, lane 1). The remaining enzyme molecules, however, successfully elongated their RNAs passed site Ia in the presence of Sarkosyl (Fig. 8, lane 3). These observations emphasize the special properties of site Ia as a block to transcription and the site selectivity of Sarkosyl inhibition.

Fig. 8. Identification of a second Sarkosyl-sensitive step during SII-activated elongation by RNA polymerase II.

Washed elongation complexes arrested at site Ia were prepared for electrophoresis (lane I) or treated with MgCl2 (7 mM) and bovine brain SII for 30 min at 28 °C (lanes 2–4). One sample was prepared for electrophoresis (lane 2). Reactions were adjusted to 800 μM each in UTP, CTP, and GTP (lanes 3 and 4) and 0.25% Sarkosyl (lane 3) and incubated at 28 °C for 30 min before preparation for electrophoresis.

DISCUSSION

Transcript Cleavage Does Not Take Place during SII-independent Elongation

Nascent RNA cleavage requires, or is greatly stimulated by, elongation factor SII. In the absence of nucleotides, many RNA polymerase II elongation complexes cleave their RNAs (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992; Wang and Hawley, 1993).2,3 Indeed, the removal of nucleotides was critical for the initial observation of this activity. Under these conditions, RNA chain elongation cannot take place and thus it cannot compete with RNA cleavage nor can it conceal shortened RNAs that are rapidly re-extended. The growing number of complexes in which this activity has been identified can be classified into at least two types. The first are those halted (or stalled) artificially by withholding nucleotide substrate. They can be restarted after the restoration of nucleotides in the absence of added elongation factors and are therefore SII-independent. The second type is complexes that become arrested at specific genetic elements in the presence of high (0.8 mM) levels of nucleotide. Elongation factor SII can reactivate these complexes, thus we have dubbed them SII-dependent. Additionally, RNA polymerase II that has either reached a DNA terminus (“runoff,” Reines, 1992; Wang and Hawley, 1993), been arrested by a DNA-bound drug,1 or that has incorporated a chain terminating nucleotide,1 displays SII-activated, nascent RNA cleavage. These complexes are all unable to extend their nascent RNA suggesting that both the inability to extend an RNA chain and the presence of SII are required in order to observe nascent RNA cleavage. Thus, we thought that SII, at levels sufficient to allow read-through, would not activate RNA cleavage during SII-independent chain elongation. This prediction is borne out in experiments in which we examined the time course of RNA chain elongation at SII-independent sites. Although shortened RNAs were readily detected when SII-dependent elongation complexes were challenged with SII (Reines et al., 1992; Fig. 6A), these intermediates were not observed during elongation by SII-independent elongation complexes, nor were shortened intermediates trapped by the incorporation of chain-terminating nucleotides (Figs. 6, B and C, and 7). These findings strengthen the correlation between chain cleavage and SII-activated readthrough.

Upstream Translocation of the Complex Is Not Required for Nascent RNA Cleavage

What feature of an intrinsic arrest site prevents further chain elongation even in the presence of nucleotides? Template structure (bending) is an important feature of the site from a human histone gene studied here (Kerppola and Kane, 1990). Tracts of A-T base pairs are determinants of both the efficiency of this arrest signal and the unusual template conformation of the region. This sequence element could influence the ability of the enzyme to move along the DNA helix (Kerppola and Kane, 1990). Alternatively, or in addition, the U-rich 3′-end of the resulting nascent RNA may predispose RNA polymerase II to become arrested through a structural rearrangement involving displacement of a weakly base paired 3′-end from the transcription bubble (Izban and Luse, 1993b).

SII facilitates transcription by RNA polymerase II through different kinds of blockages. Therefore, it seems unlikely that SII actively reverses the blockage itself, for example, by removing an arresting DNA-bound protein (Reines and Mote, 1993). Instead, the common feature of SII-dependent read-through at many arrest sites is nascent RNA cleavage. One hypothesis for the mechanism of SII stimulation is that arrested RNA polymerase II can move away (“backward”) from a blockage site (Reines, 1992). In this model, RNA cleavage may serve two functions: 1) to move RNA polymerase II upstream on the template, and 2) to allow repeated attempts at transcription through a specific template region. Translocation of RNA polymerase II away from the site could allow DNA “unbending” or the resolution of other kinds of-blockages and subsequently, improved readthrough upon a second pass (Reines, 1992; Richardson, 1993; Kassavetis and Geiduschek, 1993).

Using exo III as a probe, we show that upstream translocation of the complex, although detectable after extensive cleavage of RNA, was not observed during the small amount of shortening (7–9 bases) required for reactivation of the arrested complex. Thus, models that postulate that upstream movement of RNA polymerase II is causally involved in readthrough must be reevaluated. It remains possible that a conformational rearrangement of the distorted helix takes place in the absence of upstream translocation of the enzyme on DNA. Indeed, a conformational change in the form of downstream movement of the exo III boundaries is detected after cleavage to the first intermediate (Fig. 4). Thus, a structural rearrangement of the complex does accompany initial RNA shortening

The exonuclease III boundaries define a “footprint” of the elongation complex. The elongation complex encompasses 33–39 bp depending upon the particular complex being examined. This protected region is smaller than that previously described for DNase I footprints of promoter-proximal elongation complexes (Linn and Luse, 1991). In that work, complexes that synthesized a 15-base RNA displayed footprints of at least 44 and 54 bp on the template and non-template strands, respectively. Synthesis of a 35-base RNA resulted in a footprint of 43 to ≈50 bp, on the template and non-template strands, respectively. A recent study also described DNase I footprints of highly purified calf thymus RNA polymerase II halted on dC-tailed templates by withholding nucleotides (Rice et al., 1993). These workers found footprint sizes on the non-template strand of 42–44 bp (“full” protection) to 48–55 (including “partial” protection) for three complexes having synthesized 135-, 138-, or 143-base RNAs. The reasons for these variations are unknown but could be due to differences in the transcription systems, template sequences, or footprinting nucleases. Interestingly, we find that the arrested complex has only 10–12 base pairs between the 3′-end of the RNA chain and the leading boundary of the complex. This distance increases to 19 bp after cleavage to the first intermediate, approximately the amount seen for the SII-independent complexes at G218/ 220 and G226 (Fig. 5, D and E) and those described by Rice et al. (1993; 18, 21, and 23 bp for their three complexes) and Linn and Luse (1991; ≥19 and ≥ 26 bp for their two complexes). This is consistent with a model in which RNA chain elongation fills a product groove on the enzyme before translocation is required (Surratt et al., 1991; Borukhov et al., 1993; and see below). Arrest may result in the unusually long extension of the nascent RNA during the final translocation step, perhaps because translocation is hindered by this template region. We expect that normally, the product site is emptied by translocation of the elongation complex downstream. RNA cleavage could provide an alternative means of emptying this site for an arrested complex (Surratt et al., 1991; Borukhov et al., 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b)

Considering that the cleaved RNA chain must eventually be extended up to and past the original arrest site, how does RNA cleavage facilitate readthrough? If arrest results in loss of contact of the phosphodiester bond-synthesizing catalytic site with the nascent RNA’s 3′-end, this could explain the inability of the enzyme to elongate RNA chains. One possibility, suggested previously for bacterial RNA polymerase and RNA polymerase II (Borukhov et al., 1993; Izban and Luse, 1993b) and consistent with our findings, is that RNA cleavage restores continuity of the polymerization catalytic head with the RNA’s 3′-end. The data presented here suggest that this takes place with a minimal change in the complex’s DNA contacts. Moreover, these alterations are, perhaps counter-intuitively, in the downstream direction. At site Ia, only a certain fraction of the enzyme encountering the site suffers the insult of arrest. In the absence of SII, approximately 40–50% of the RNA polymerase II molecules pass through site Ia upon their first encounter with it (Reines et al., 1992). Apparently, this population of enzyme proceeds past site Ia without the assistance of SII and without transcript cleavage. Consistent with this idea, Sarkosyl does not influence the fraction of molecules successful in readthrough during their first encounter with site Ia (Reines et al., 1989).7 If the probability of readthrough is 50%/RNA polymerase/encounter, after six iterations of cleavage and resynthesis, we calculate that 99% of the population of molecules will read through this site.

Observations on lac repressor-mediated arrest demonstrate that RNA polymerase II can be reactivated for readthrough by SII but that removal of the lac repressor blockade with isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside results in SII-independent elongation (Reines and Mote, 1993). Hence, some forms of arrest are reversible and do not absolutely require SII or RNA cleavage. It is possible that DNA-bound protein represents a mechanistically distinct type of arrest compared to that directed by DNA sequence, although readthrough of DNA-binding proteins may still require multiple rounds of cleavage and resynthesis.

We have tested the idea that multiple cycles of RNA cleavage-resynthesis are required for complete readthrough of site Ia in experiments with the SII-inhibitor, Sarkosyl (Fig. 8). We find that 43% of the enzyme molecules have bypassed their Sarkosyl-sensitive step after RNA cleavage. The remaining molecules appear to require one or more additional rounds of cleavage. Similar findings have been made for the reaction carried out by the Drosophila elongation complex.3

The Extent of Cleavage Required for Reactivation of Complex Ia

Two major intermediates have been defined when nucleotide-depleted complexes arrested at site Ia cleave their transcripts (Reines, 1992, Fig. 1C, this work). The cleavage pattern is suggestive of endonucleolytic cleavage of the transcript which would be consistent with recent findings showing that 7–14-base oligonucleotides are removed from the 3′-end of nascent RNAs by SII-dependent elongation complexes (Izban and Luse, 1993b). We propose that our first intermediate results from the removal of a 7-, 8-, or 9-base oligonucleotide in a single step (recall that transcript Ia is a family of three 5′-coterminal RNAs with 3′-ends falling over 3 consecutive U residues) and therefore that only a single phosphodiester bond needs to be broken in order to reactivate this arrested complex. Other workers (Wang and Hawley, 1993), however, have suggested that cleavage takes place in single nucleotide increments. Thus, this conclusion must remain tentative until the product removed from the first intermediate is identified. A careful analysis of the kinetics of RNA cleavage during SII-facilitated elongation through site Ia (in the presence of nucleotides) reveals that RNAs are only shortened by seven to nine nucleotides before the chains are re-extended (Fig. 6A). In the absence of nucleotides, this RNA is shortened further (Reines, 1992 and Fig. 6A; this work) and RNA shortening by up to 100 nucleotides is possible for some complexes (Reines et al., 1992). This implies that for complex Ia shortening proceeds in the presence of nucleotides until chain elongation is again possible, which in this case occurs after seven to nine nucleotides have been removed from the arrested RNA. Exo III footprinting shows that RNA polymerase II does not shift its boundaries upstream after cleavage to this point, although further cleavage does result in the upstream translocation of the enzyme. Hence, we suggest that RNA polymerase II need not translocate upstream during the SII reactivation process. As mentioned above, structural rearrangements of other types involving the template, the transcript, and/or the enzyme are likely to be involved in conversion of the arrested complex into an elongating complex.

The discontinuous movement of RNA polymerase along DNA during RNA chain growth has been observed for E. coli RNA polymerase (Krummel and Chamberlin, 1989,1992) and RNA polymerase II (Linn and Luse, 1991; Rice et al., 1993). These workers showed that the downstream boundary of RNA polymerase in ternary complexes does not move forward regularly as RNA chains are extended. We show here a similar phenomenon for RNA chain shortening by RNA polymerase II. The elongation complex boundaries do not move upstream after the RNA is shortened by up to nine bases; in fact they move downstream. Shortening of the RNA by an additional two bases then results in a 1–3 bp upstream movement of the complex. Perhaps significantly, cleavage brings the 3′-end of the RNA into a position, relative to the exo III boundaries, more characteristic of SII-independent elongation complexes. This may explain why RNA cleavage by SII-dependent and SII-independent complexes releases oligonucleotides of different sizes (Izban and Luse, 1993b).

Mechanism of α-Amanitin Inhibition

Inhibition of the activity of RNA polymerase II by α-amanitin is a defining feature of this enzyme (Kedinger et al., 1970; Lindell et al., 1970; Jacob et al., 1970). This toxin does not influence DNA binding by RNA polymerase II. It binds to the enzyme but does not alter the enzyme’s affinity for nucleotides nor does it disrupt assembled elongation complexes. Early studies led to the conclusion that α-amanitin inhibits phosphodiester bond formation (Cochet-Meilhac et al., 1974). α-Amanitin-resistant phosphodiester bond formation by RNA polymerase II has, however, been observed and was attributed to a brief period of chain elongation that precedes translocation of the enzyme on DNA (Vaisius and Wieland, 1982; Grachev et al., 1986; Riva et al., 1987; de Mercoyrol et al., 1989; Job et al., 1992). Hence, it was suggested that it is the translocation step of RNA polymerase II’s transcription cycle that is affected by α-amanitin.

During the course of the work described here, we tested the effect of α-amanitin on RNA chain elongation by a specific elongation complex. Consistent with the idea that translocation is inhibited by α-amanitin, we find that for at least one specific RNA polymerase II elongation complex, the formation of a few (≈8) phosphodiester bonds is possible in the presence of levels of the drug that completely abolish the synthesis of other RNAs (Fig. 6B). This is also consistent with the finding that α-amanitin-resistant synthesis of large poly(rG) chains is possible on homopolymer templates (Job et al., 1992). This presumably represents slippage synthesis, a situation that would not require enzyme translocation. A previous report mentioned similar findings of unusual α-amanitin-resistant synthesis by a specific RNA polymerase II elongation complex (Linn and Luse, 1991). We have confirmed that α-amanitin inhibits nascent RNA cleavage (Reines, 1992; Izban and Luse, 1992; Wang and Hawley, 1993). Cleavage is accompanied by translocation, albeit a small downstream one. The fact that α-amanitin inhibits RNA cleavage, which is associated with displacement of the complex (Fig. 4, lanes 22–29), suggests that this movement may represent an isomerization required for the cleavage reaction and is consistent with the idea that the toxin prevents translocation of the enzyme on DNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. Boss, L. Coluccio, C. Moran, R. Conaway, and J. Conaway for reading the manuscript and/or helpful discussion and Drs. M. Chamberlin, D. Price, D. Luse, and C. Kane for information prior to publication.

Footnotes

J. Mote, Jr., P. Ghanouni, and D. Reines, manuscript in preparation.

K. Christie and C. M. Kane, manuscript submitted.

H. Guo and D. Price, manuscript submitted.

The abbreviations used are: NTPs, nucleoside triphosphates; bp, base pairs; ddNTPs, 2′, 3′-dideoxynucleoside triphosphates; exo III, E. coli exonuclease III; HAP, hydroxylapatite.

W. Gu, W. Powell, J. Mote, Jr., and D. Reines, unpublished results.

W. Gu, unpublished results.

W. Powell, unpublished results.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-46331 and American Cancer Society Grant JFRA-394.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EMBL Data Bank with accession number(s) L20863.

References

- Bengal E, Goldring A, Aloni Y. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18926–18932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borukhov S, Polyakov A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8899–8902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borukhov S, Sagitov V, Goldfarb A. Cell. 1993;72:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochet-Meilhac M, Chambon P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;353:160–184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(74)90182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway JW, Bond MW, Conaway RC. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:8293–8297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway RC, Conaway JW. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2962–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mercoyrol L, Job C, Job D. Biochem J. 1989;258:165–169. doi: 10.1042/bj2580165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilat D, Hochberg M, Fischel R, Laskov R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3818–3822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.12.3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilat D, Hochberg M, Pumphrey J, Rudikoff S. J Immunol. 1984;133:489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garielio P, Bellard M, Chambon P. FEBS Letts. 1974;44:330–333. [Google Scholar]

- Grachev MA, Hartman GR, Maximova TG, Mustaev AA, Schaffner AR, Seiber H, Zaychikov EF. FASEB Letts. 1986;200:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler J, Shuman S. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2166–2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes BC, LeBlanc JF, Hawley DK. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11539–11547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izban MG, Luse DS. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1342–1356. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izban MG, Luse DS. J Biol Chem. 1993a;268:12864–12873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izban MG, Luse DS. J Biol Chem. 1993b;268:12874–12885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob ST, Sajdel EM, Munro HN. Nature. 1970;225:60–62. doi: 10.1038/225060b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job C, Shire D, Sure V, Job D. Biochem J. 1992;285:85–90. doi: 10.1042/bj2850085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP. Science. 1993;259:944–945. doi: 10.1126/science.7679800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedinger C, Gniazdowski M, Mandel JL, Jr, Gissinger F, Chambon P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)91099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK, Kane CM. Biochemistry. 1990;29:269–278. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK, Kane CM. FASEB J. 1991;5:2833–2842. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.13.1916107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummel B, Chamberlin MJ. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7829–7842. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummel B, Chamberlin MJ. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:221–237. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell TL, Weinberg F, Morris PW, Roeder RG, Rutter WJ. Science. 1970;170:447–449. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3956.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn SC, Luse DS. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;2:1508–1522. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam AM, Gilbert W. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg D, Roeder RG. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3331–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10510–10517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3795–3800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D. In: Transcription. Conaway R, Conaway J, editors. Raven Press; New York: 1993. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Reines D, Mote J., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1917–1921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D, Wells D, Chamberlin MJ, Kane CM. J Biol Chem. 1987;196:299–312. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D, Chamberlin MJ, Kane CM. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10799–10809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D, Ghanouni P, Li Q-q, Mote J. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15516–15522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GA, Chamberlin MJ, Kane CM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:113–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JP. Crit Rev Biochem & Mol Biol. 1993;28:1–30. doi: 10.3109/10409239309082571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva M, Schaffner AR, Sentenac A, Hartmann GR, Mustaev AA, Zaychikov EF, Grachev MA. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14377–14380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluder AE, Greenleaf AL, Price DH. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8963–8969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkowski J, Das A. Genetics. 1992;130:411–428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CA, Groudine M. Oncogene. 1990;5:777–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt CK, Milan SC, Chamberlin MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7983–7987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi A, Conger K, Garrett KP, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Arai N. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3250. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.12.3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisius AC, Wieland T. Biochemistry. 1982;21:3097–3101. doi: 10.1021/bi00256a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke MW, Roeder RG, Sawadogo M. Science. 1988;241:1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.3413495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke MW, Sawadogo M, Roeder RG. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:342–344. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.1.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Hawley DK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:843–847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiest DK, Wang D, Hawley DK. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7733–7744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]