Abstract

Background

Deep neck infections (DNI) can originate from infection in the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck. DNI can be managed without surgery, but there are cases that need surgical treatment, especially in the case of mediastinal involvement. The aim of this study is to identify clinical features of DNI and analyze the predisposing factors for mediastinal extension.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed medical records of 56 patients suffering from DNI who underwent cervical drainage only (CD group) and those who underwent cervical drainage combined with mediastinal drainage for descending necrotizing mediastinitis (MD group) from August 2003 to May 2009 and compared the clinical features of each group and the predisposing factors for mediastinal extension.

Results

Forty-four out of the 56 patients underwent cervical drainage only (79%) and 12 patients needed both cervical and mediastinal drainage (21%). There were no differences between the two groups in gender (p=0.28), but the MD group was older than the CD group (CD group, 44.2±23.2 years; MD group, 55.6±12.1 years; p=0.03). The MD group had a higher rate of co-morbidity than the CD group (p=0.04). The CD group involved more than two spaces in 14 cases (32%) and retropharyngeal involvement in 12 cases (27%). The MD group involved more than two spaces in 11 cases (92%) and retropharyngeal involvement in 12 cases (100%). Organism identification took place in 28 cases (64%) of the CD group and 3 cases of (25%) the MD group (p=0.02). The mean hospital stay of the CD group was 21.5±15.9 days and that of the MD group was 41.4±29.4 days (p=0.04).

Conclusion

The predisposing factors of mediastinal extension in DNI were older age, involvement of two or more spaces, especially including the retropharyngeal space, and more comorbidities. The MD group had a longer hospital stay, higher mortality, and more failure to identify causative organisms of causative organisms than the CD group.

Keywords: Infection, Neck, Mediastinitis

INTRODUCTION

Deep neck infections (DNI) can originate from infection in the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck. The primary origin of DNI is unknown in most cases, but it can be caused by dental problems, cervical lymphadenitis, sialoadenitis, acute tonsillitis, and peritonsillar abscess [1]. Most patients of DNI can be treated with a broad spectrum of intravenous antibiotics without complications. However, complications such as airway obstruction in patients with lateral pharyngeal cavity or peritonsilar abscess, deep vein thrombosis, mediastinitis, pneumonitis, laryngeal edema, and encephalitis can occur [1]. Some DNI require surgical treatment, especially in cases of mediastinal involvement, known as descending necrotizing mediastinitis (DNM). Many acute mediastinal infections result from esophageal perforation or infection following a trans-sternal cardiac procedure. However, they may result from oropharyngeal infection spreading along the fascial planes into the mediastinum [2-5]. Criteria of diagnosing DNM were clearly established by Estrera in 1983 [2]. These included clinical manifestations such as severe infection, characteristic radiology features, necrotizing mediastinal infection revealed at operation or autopsy, and the relationship of oropharyngeal infection to the development of DNM. Endo et al. [3] classified DNM into three types according to the extension of DNM using computed tomography (CT). Type I is a localized disease above the carina, Type II A is characterized by diffuse anterior mediastinal involvement, and Type II B involves both the anterior and posterior mediastinum [3].

We report the surgical results of the cervical drainage group in DNI compared with the group to which mediastinal drainage was added. The clinical features and predisposing factors of DNI progressing to DNM were analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The medical records of patients who underwent surgical treatment for DNI and DNM from August 2003 to May 2009 were reviewed retrospectively. Their demographics, etiologies associated with systemic diseases (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and chronic renal failure), preoperative condition (sepsis), disease interval, infectious origin, bacteriology, radiology, duration of hospitalization, and outcomes were reviewed. Sepsis was defined as high fever (>38.2℃), unstable vital signs (blood pressure <90 mmHg, respiratory rate >25/min), leucopenia (white blood cell <4,000/mm3), thrombocytopenia (platelet <100,000/mm3), oliguria (0.5 mL/kg/hr), or prolonged coagulation time (activated partial thromboplastin time >60 sec or international normalized ratio >1.5). In the present article, 56 patients were suffering from DNI; 44 patients received cervical drainage only (CD group) and 12 patients needed both cervical and mediastinal drainage for mediastinal involvement (MD group).

Neck and chest CT scans were performed on all patients clinically suspected of DNI. Shortly after the criteria of Estrera were fulfilled, nil per os and fluid therapy was initiated. Empiric antibiotics, including third-generation cephalosporin and clindamycin, were administered immediately. Appropriate antibiotics for causative organisms were given based on the results of culture identification.

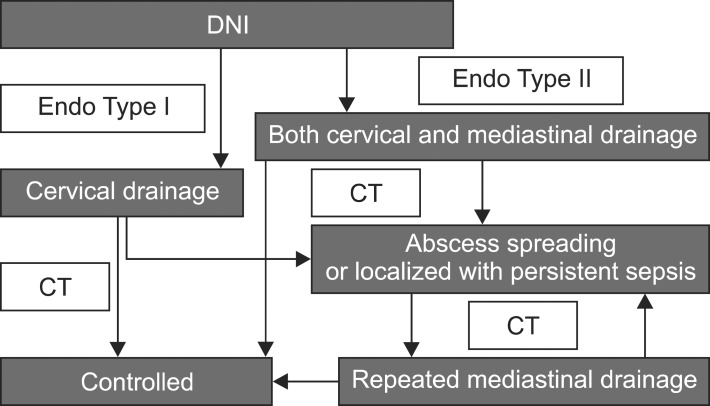

Type I DNM was managed with cervical drainage only and Type II DNM was treated with both cervical and mediastinal drainage by Endo's classification. For the cervical drainage, we used an anterior approach to the DNI and maintained open drainage until the wound was clear. When follow-up CT scans showed that the disease had improved, treatment was terminated. However, when the CT scan showed an abscess spreading or localized persistent septic manifestation, repeated mediastinal drainage was performed. The CT scans were performed at the third, seventh, and fourteenth postoperative day routinely, or whenever routine chest X-rays showed abnormal findings (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm of surgical management for deep neck infections (DNI) and descending necrotizing mediastinitis. CT, computed tomography.

All data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. SPSS ver. 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

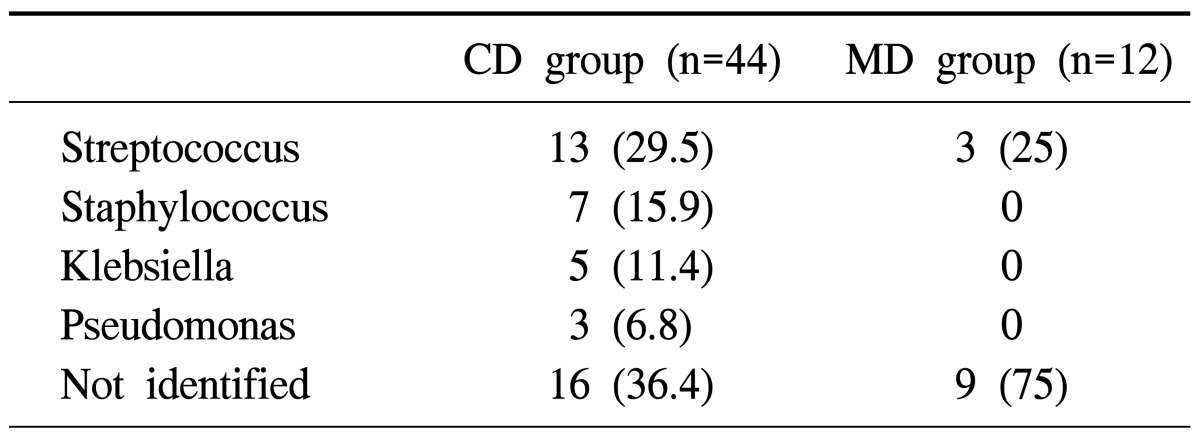

Fifty-six patients with DNI were treated in our institution. Of those, 44 patients received cervical drainage only (CD group), and 12 patients received both cervical and mediastinal drainage (MD group). The mean age of the CD group, consisting of 26 males and 18 females, was 44.2±23.2 years, and the MD group, consisting of 5 males and 7 females, was 55.6±12.1 years. There were no differences between the two groups in gender (p=0.28), but the MD group was older (p=0.03). Preoperative comorbidities were liver cirrhosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal disease requiring regular hemodialysis. The MD group had comorbidity in 7 cases (58%) and the CD group had co-morbidity in 12 cases (27%) (p=0.04). The disease interval was similar in both groups (the CD group, 6.8±6.8 days; the MD group, 6.3±4.0 days; p=0.79). The origin of infection for the CD group showed 39 pharyngeal infections (89%) and 5 dental infections (11%). The MD group contained 9 pharyngeal infections (75%) and 3 dental infections (25%). The difference in the origins of infection between the two groups was not statistically significant (p=0.23). In 28 cases (64%) of the CD group and 3 cases (25%) of the MD group organism identification of the infection was successful. The MD group had more negative identification of causative organisms than the CD group (p=0.02). Causative organisms of the CD group infections were 13 cases of Streptococcus (29.5%), 7 of Staphylococcus (15.9%), 5 of Klebsiella (11.5%), and 3 of Pseudomonas (6.8%), while 16 remained unidentified (36.4%) (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Bacteriology of the CD groupa) and MD groupb)

Values are presented as number (%).

a)CD group: cervical drainage only.

b)MD group: both cervical and mediastinal drainage.

Table 2.

Surgical results of the CD groupa) and MD groupb)

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

a)CD group: cervical drainage only.

b)MD group: both cervical and mediastinal drainage.

c)Statistically significant.

d)Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, or chronic renal failure.

e)Duration from initial symptom to admission.

The infections of the CD group was involved in two or more spaces in 14 cases (32%) and had retropharyngeal involvement in 12 cases (27%). The infections of the MD group were involved in two or more spaces in 11 cases (92%) and retropharyngeal involvement in 12 cases (100%). Involvement in two or more spaces, especially the retropharyngeal space, indicated a higher risk of mediastinal spreading (p=0.00). The mean hospital stay of the CD group was 21.5±15.9 days and that of the MD group was 41.4±29.4 days. The MD group had a longer hospital stay (p=0.04). There was no mortality in the CD group but there were 2 cases of mortality (17%) in the MD group (p=0.01) (Table 2).

The two mortalities in the MD group were male, in septic condition preoperatively, had Type II B disease, and had Streptococcus identified. The patient who was diagnosed with DNM 11 days after initial cervical drainage died from multi-organ failure despite three thoracotomies followed by a median sternotomy. The other patient's referral to our institution was delayed after the onset of symptoms, and he died from intractable shock.

DISCUSSION

DNI is caused by pharyngeal infection, odontogenic infection, cervical lymphadenitis, parotitis, sinusitis, or cervical trauma [3-6]. The most common cause of DNI is odontogenic infection, arising from the second or third molar. Odontogenic and peritonsillar abscesses can rupture into the submandibular and parapharyngeal spaces. The parapharyngeal space connects with all the major fascial spaces [7]. DNI can spread to the mediastinum through four loose connective tissue spaces: the carotid space, the retropharyngeal space, the prevertebral space, and the retrovisceral space. The retropharyngeal space is bounded by the posterior visceral fascia anteriorly and the alar fascia posteriorly. The prevertebral space is bounded by the prevertebral fascia anteriorly and the vertebral body posteriorly. The most important route of descending infection is the retrovisceral space, lying between the alar fascia and prevertebral fascia [8]. Above all, the retrovisceral space is the space most vulnerable to the extension of oropharyngeal infection to the mediastinum [5,6,9,10], and involvement of two or more spaces is a significant predicting factor for deep neck infection complications [1]. In this study, involving more than two spaces is a predicting factor for DNI spreading (p<0.05). The rapid spread of DNI into the mediastinum is facilitated by gravity, respiration, the negative intrathoracic and pleural pressure during inspiration, and the absence of barriers in the fascial planes [4-6,9]. Many studies have shown that coexisting morbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), alcoholism, and chronic renal failure can be attributed to the extension of DNI into the mediastinal space [4-6,9]. One study also showed that the presence of coexisting morbidities like DM increased the occurrence of complication by more than 5 times [1]. Our study further showed that coexisting morbidity is a risk factor for the extension of DNI into the mediastinal space (p<0.05).

History-taking, physical examination, and clinical suspicion are crucial for initial diagnosis of DNM because clear symptoms may not exist. The interval between the onset of symptoms and admission is the main reason for delayed diagnosis [4,6]. Simple radiography plays a limited role in diagnosis. CT can provide high accuracy for the detection and the spread of DNM from DNI [4,6,8,9,11,12]. In 1999, Endo et al. [3] classified DNM into three types according to the extension of DNM as diagnosed by CT and proposed differential surgical management according to this classification. Type I is a localized disease above the carina, Type II A is a diffuse disease with anterior mediastinal involvement, and Type II B has both anterior and posterior mediastinal involvement. Type I can be managed with transcervical mediastinal drainage. Type II A requires transcervicotomy and mediastinal drainage through a subxiphoid approach. Type II B should receive treatment through standard thoracotomy [3]. In this article, all the patients of the MD group were Type II B and received thoracotomy. DNM caused by DNI requires aggressive medical and surgical management, and surgical management should combine cervical drainage with mediastinal drainage. The primary non-surgical treatment of DNM caused by DNI includes intravenous administration of empirical broad spectrum antibiotics [5,6,9]. In our institution, third-generation cephalosporine and clindamycin were the first-line drugs used for DNI and DNM. Appropriate antibiotics were adapted to the causative organisms based on culture identification. Both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria can be causative organisms of DNI and DNM. The most common pathogen of DNM was mixed aerobic and anaerobic organism although Streptococcus was the most common pathogen [6,7,10,11]. In our study, Streptococcus species were the most common pathogen for DNI and DNM.

A number of surgical approaches have been reported for optimal mediastinal drainage including a transcervical approach and several transthoracic approaches such as thoracotomy, sternotomy, clamshell incision, a subxiphoid approach, and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) [4,5,11,13]. Many authors have suggested that transthoracic approaches are mandatory for mediastinal drainage regardless of the level of involvement [11,13,14]. However, some authors have suggested that if DNM is limited to the upper mediastinum, it can be adequately drained using the transcervical approach. Formal thoracotomy should be reserved for cases extending below the plane of the tracheal bifurcation [7]. Median sternotomy and clamshell incision have a possible risk of osteomyelitis [4,5,11,13]. Some surgeons prefer thoracotomy to VATS for several reasons [11,13,14]. Thoracotomy tends to be less time-consuming for pleural adhesiolysis and provides a tactile sensation for blunt dissection of the paraesophageal space. In our institute, thoracotomy was the standard method for mediastinal approaches. When mediastinal involvement was extensive, bilateral mediastinal drainage was performed. The mediastinal space was irrigated with warm saline via multiple chest tubes (32 Fr) for very thick and turbid discharge. We did not perform tracheostomy except when there was a need for prolonged ventilator care. Thoracoscopic drainage could be useful when the patient is hemodynamically stable, but not under septic conditions [6,9,14,15]. Follow-up CT was helpful to determine the adequacy of drainage and detect recurrent abscess or progression of DNM [6,9]. A CT scan should be obtained routinely every 48 hours until the disease improves [6,9].

In 1938, Pearse [16] reported the first series of 110 patients with DNM. The mortality rate of DNM is still 20% to 50%, although its incidence is low due to the wide use of antibiotics and improved oral hygiene [4-6,9]. In 1982, Estrera et al. [2] reported on 10 DNI patients who progressed to DNM treated with cervical drainage and mediastinal drainage, and who showed a 40% mortality rate. The recent reported mortality for DNM has been 16.5% to 36% [7,10]. Mortality rates in this study were comparable (17%).

CONCLUSION

Complications in DNI could result in fatal morbidity and mortality in patients with DNM. This article compared DNI patients who progressed to DNM and those who did not.

Among 56 patients, 44 patients underwent cervical drainage only, and 12 patients needed both cervical and mediastinal drainage. Age, co-morbidity, and the number of spaces involved, especially the retropharyngeal space, are predicting factors for mediastinal spreading of DNI. The MD group had a longer hospital stay, higher mortality, and more negative identification of causative organisms than the CD group. Despite appropriate treatment for DNI and DNM, morbidity and mortality rates were not negligible in mediastinal involvement.

Footnotes

This study was financially supported by research fund of Chungnam National University in 2010.

References

- 1.Lee JK, Kim HD, Lim SC. Predisposing factors of complicated deep neck infection: an analysis of 158 cases. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:55–62. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estrera AS, Landay MJ, Grisham JM, Sinn DP, Platt MR. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;157:545–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endo S, Murayama F, Hasegawa T, et al. Guideline of surgical management based on diffusion of descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;47:14–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03217934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridder GJ, Maier W, Kinzer S, Teszler CB, Boedeker CC, Pfeiffer J. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: contemporary trends in etiology, diagnosis, management, and outcome. Ann Surg. 2010;251:528–534. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c1b0d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marty-Ane CH, Berthet JP, Alric P, Pegis JD, Rouviere P, Mary H. Management of descending necrotizing mediastinitis: an aggressive treatment for an aggressive disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:212–217. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Freitas RP, Fahy CP, Brooker DS, et al. Descending necrotising mediastinitis: a safe treatment algorithm. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheatley MJ, Stirling MC, Kirsh MM, Gago O, Orringer MB. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: transcervical drainage is not enough. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:780–784. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(90)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corsten MJ, Shamji FM, Odell PF, et al. Optimal treatment of descending necrotising mediastinitis. Thorax. 1997;52:702–708. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.8.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman RK, Vallieres E, Verrier ED, Karmy-Jones R, Wood DE. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: an analysis of the effects of serial surgical debridement on patient mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:260–267. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu JH, Lim SP, Lee SK, et al. Clinial analysis of surgical management for descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;41:463–468. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue Y, Gika M, Nozawa K, Ikeda Y, Takanami I. Optimum drainage method in descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:189–192. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2004.105395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scaglione M, Pinto A, Romano S, Giovine S, Sparano A, Romano L. Determining optimum management of descending necrotizing mediastinitis with CT: experience with 32 cases. Emerg Radiol. 2005;11:275–280. doi: 10.1007/s10140-005-0422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata T, Sekine Y, Shibuya K, et al. Early open thoracotomy and mediastinopleural irrigation for severe descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marty-Ane CH, Alauzen M, Alric P, Serres-Cousine O, Mary H. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Advantage of mediastinal drainage with thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min HK, Choi YS, Shim YM, Sohn YI, Kim J. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: a minimally invasive approach using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:306–310. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearse HE. Mediastinitis following cervical suppuration. Ann Surg. 1938;108:588–611. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193810000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]