Abstract

Despite much research, our understanding of the rules by which cis-regulatory sequences are translated into expression levels is still lacking. We devised a method for obtaining parallel and highly accurate expression measurements of thousands of fully designed promoters, and applied it to measure the effect of systematic changes to location, number, orientation, affinity and organization of transcription factor (TF) binding sites and of nucleosome disfavoring sequences. Our analyses reveal a clear relationship between expression and binding site number, and TF-specific dependencies of expression on the distance between sites and gene starts including a striking ~10bp periodic relationship. We also demonstrate the utility of our approach for measuring TF sequence specificities and sensitivity of TF sites to surrounding sequence context, and for profiling the activity of most yeast transcription factors. Our method is readily applicable for studying both the cis and trans effects of genotype on transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational control.

Introduction

Deciphering the mapping between DNA sequence and expression levels is key for understanding transcriptional regulation. However, despite many studies, the quantitative effect on expression of even the most basic organizational features of promoters are still poorly understood. For example, even for a single transcription factor (TF) binding site, we know little about the quantitative effects on expression levels of its location, orientation, and affinity; whether these effects are general, factor-specific, and/or promoter-dependent; and how they depend on the underlying nucleosome organization.

In principle, such questions can be answered through accurate expression measurements of promoters in which the above elements are systematically varied. Indeed, several medium-scale1–3 and large-scale4–6 libraries were created in bacteria and yeast, in which regulatory elements were randomly ligated or mutagenized and the expression of the resulting promoters was measured. These studies provided much insight, but due to their random nature, they are not ideal for addressing the above questions. For example, studying the effect of binding site location on expression requires measurements of promoters that differ only in the location of the site and sampling many such locations. Clearly, many of the desired promoters would be missing from randomly ligated libraries. Indeed, controlled design of such promoter variants7–10 led to profound insights, but since the variants were constructed one by one, time and cost considerations have limited the scale of previous studies to at most dozens of variants.

A recent study demonstrated the benefit of using thousands of designed sequences for analyzing the effect of systematic mutations to six promoters11. However, this method assays promoter strength using in vitro transcription and thus has limited utility for understanding promoter activity in vivo. While our paper was in review, two other methods were devised for parallel measurement of promoter activity in vivo12,13. One method assayed the effect of an impressive library of >100,000 random mutations in three mammalian enhancers12, but the random nature of the libraries limits this method’s utility for systematic dissection of regulatory logic. The other method13 used programmable microarrays14 to measure the effect of systematically designed mutations in two mammalian enhancers.

Here, we devised a high-throughput fluorescence-based method for obtaining parallel and highly accurate expression level measurements of thousands of fully designed promoters. Our approach differs from and has several advantages over previous methods. First, our parallel expression measurements are in excellent agreement with those of isolated strains (R2=0.99), considerably better than the agreement reported by Melnikov et al.13 (R2=0.45–0.75). Highly accurate expression measurements are critical for a quantitative understanding of transcriptional regulation. Second, in contrast to both recent methods12,13 that require a barcode within the RNA reporter, our method can avoid barcodes by fully sequencing each promoter, although our present study incorporated a barcode upstream of the designed promoter. Barcodes within the RNA affect reporter expression and thus limit accuracy13. Third, while both published methods measure mean expression level over a cell population, our method obtains cell-to-cell (noise) expression variability measurements for each promoter, which also agree well with isolated strain measurements (R2=0.43, Fig. S1). Finally, by using protein fluorescence and not RNA as the readout, we can also study translational control, e.g., with libraries that alter the 5’ UTR or the codons of the fluorescent reporter. In addition, the need to physically couple a proximal barcode to the examined variable region limits both previous methods12,13 to studying cis-effects, whereas our method can be used to examine the effects of sequence variation on fluorescent protein expression in trans.

We applied our approach to design a library of 6500 promoters that directly measures several grammatical rules of transcriptional regulation such as the effect on expression of binding site location, number, orientation, and affinity. Our results provide insights into principles of transcriptional regulation, including a clear logistic function relationship between expression and site number; a dominance of TF identity over site number in determining high expression levels; a surprisingly large effect on expression of even small 1–7bp changes in site location; and for one TF, a striking ~10bp periodic relationship between expression and site location. Our approach can be adapted to other genomic regions and organisms to unravel diverse types of both cis and trans mappings between sequence and phenotype.

Results

Parallel expression measurements of thousands of designed promoters

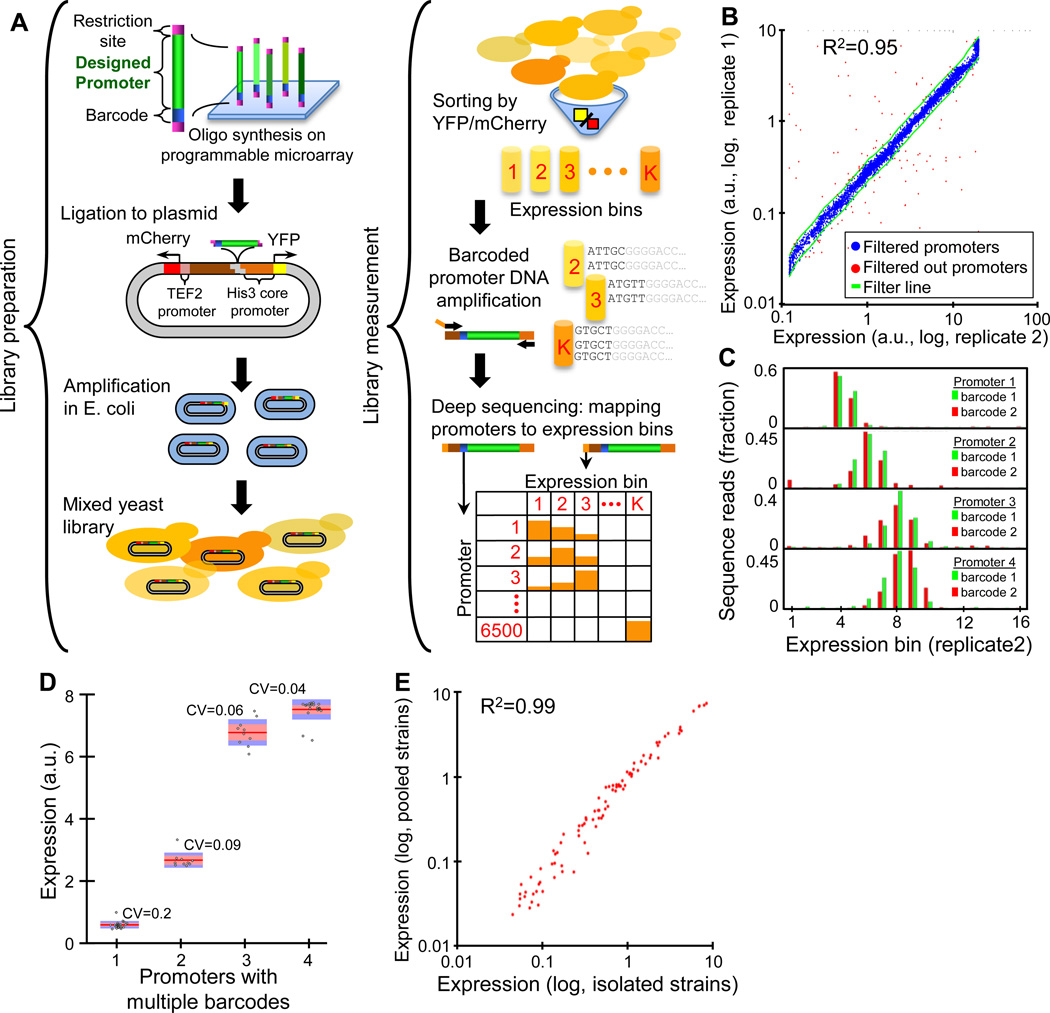

We designed a library of 6500 different promoters that address diverse questions in transcriptional regulation, and devised a method for accurately measuring their expression within a single experiment (Fig. 1A). Briefly, we obtain a mixed barcoded oligonucleotide pool synthesized on Agilent programmable microarrays11,14,15 that represents our promoter library, and fuse it upstream of a ~100bp TATA containing core promoter followed by a yellow fluorescent reporter (YFP) and into a low-copy plasmid. We then amplify the library in E. coli and transform it into yeast. Finally, we sort the resulting pool of transformed cells grown in a desired condition based on YFP intensity, and use deep-sequencing to obtain a measure of the expression of each promoter based on the distribution of its sequencing reads across the sorted expression bins.

Figure 1. Obtaining accurate expression measurements for thousands of designed promoter sequences.

(A) Illustration of our experimental method. (B) Our method obtains highly reproducible expression measurements. Shown is a comparison of expression measurements (log-scale) obtained for two independent replicates done using two different cell sorting strategies (y-axis, replicate 1 sorted into 64 bins; x-axis, replicate 2 sorted into 16 bins, see Methods), along with lines (green) that correspond to a difference of 30% from the mean of the two replicates. 114 (1.75%) of the 6500 promoters that we designed fell outside the green lines and were filtered out from our analyses. (C) Barcodes have little effect on our expression measurements. Shown is the distribution of sequencing reads across the expression bins that we obtained for four pairs of promoters that differ only in their barcode sequence. See Fig. S2 for 14 additional such promoter pairs. (D) Similar to (C), but for four sets of promoters where each set contains 10 (columns 3–4) or 20 (columns 1–2) promoters that differ only in their barcode sequence. For each set, shown are the individual expression measurements (gray dots), and their median (red line), standard error (orange bar), standard deviation (blue bar), and coefficient of variation (CV, standard deviation divided by the mean). (E) Our method obtains highly accurate expression measurements. We isolated 92 individual strains from our pool of transformed yeast cells and sequenced each of them to reveal their identity. Shown is a comparison of the expression for these strains when each strain was measured in isolation using a flow cytometer (x-axis) or within a single experiment using our method (y-axis).

We designed a significant fraction of our library using sites for the two well studied transcriptional activators Gal4 and Gcn4. Accordingly, we grew the cells in galactose medium while starving for amino acids, since this condition activates both TFs. To test the generality of our conclusions, we performed all of the systematic changes to regulatory elements in two different promoter backgrounds.

We used several tests to gauge the accuracy of our approach. First, all of the designed promoters were represented in the final sequencing reads, and 94% had at least 100 reads. Second, we found that our method is highly reproducible, since independent replicates employing two different sorting strategies are highly correlated (R2=0.95, Fig. 1B). Third, we verified that the barcode has little effect, by designing 22 promoters each with 2–20 different barcodes, and finding good agreement between the expression of these promoters that differ only in their barcode (Fig. 1C–D, Fig. S2). Most critically, we isolated 92 individual clones from the mixed pool of transformed yeast cells, sequenced each of them to identify the integrated promoter, and measured the expression of each isolated clone individually using flow cytometry. Notably, we found excellent agreement (R2=0.99, Fig. 1E) between these expression measurements and those obtained using our method. Finally, since our promoters are on plasmids, we compared their expression to measurements of individual strains of 29 different genomically integrated promoters, and again found excellent agreement (R2=0.97, Fig. S3).

Together, these results demonstrate that our method can measure the expression of thousands of fully designed promoters within a single experiment and with similar accuracy to that obtained when promoters are constructed and measured individually.

Identifying functional elements in promoters using scanning mutagenesis

We first examined the utility of our method for comprehensively mapping functional elements. We selected 103bp regions from three native yeast promoters and designed separate systematic mutations across all of their non-overlapping 4bp-long segments. Such scanning mutagenesis can identify regulatory elements11, 16 and indeed, we found a significant reduction in expression when mutating putative TF sites (Fig. S4). Notably, we found similarly strong expression reductions when mutating a poly(dA:dT) tract, which disfavors nucleosome formation17–19 (Fig. S4C), suggesting a novel regulatory role for this region. In contrast, mutations of two putative TF sites in another promoter had little effect (Fig. S4B), suggesting that these sites are not functional in our tested condition. Since we can measure thousands of promoters at once, these results show that by devoting the entire library design towards mutations in native promoters, our method can systematically map functional regulatory elements.

Profiling the activity of most yeast TFs

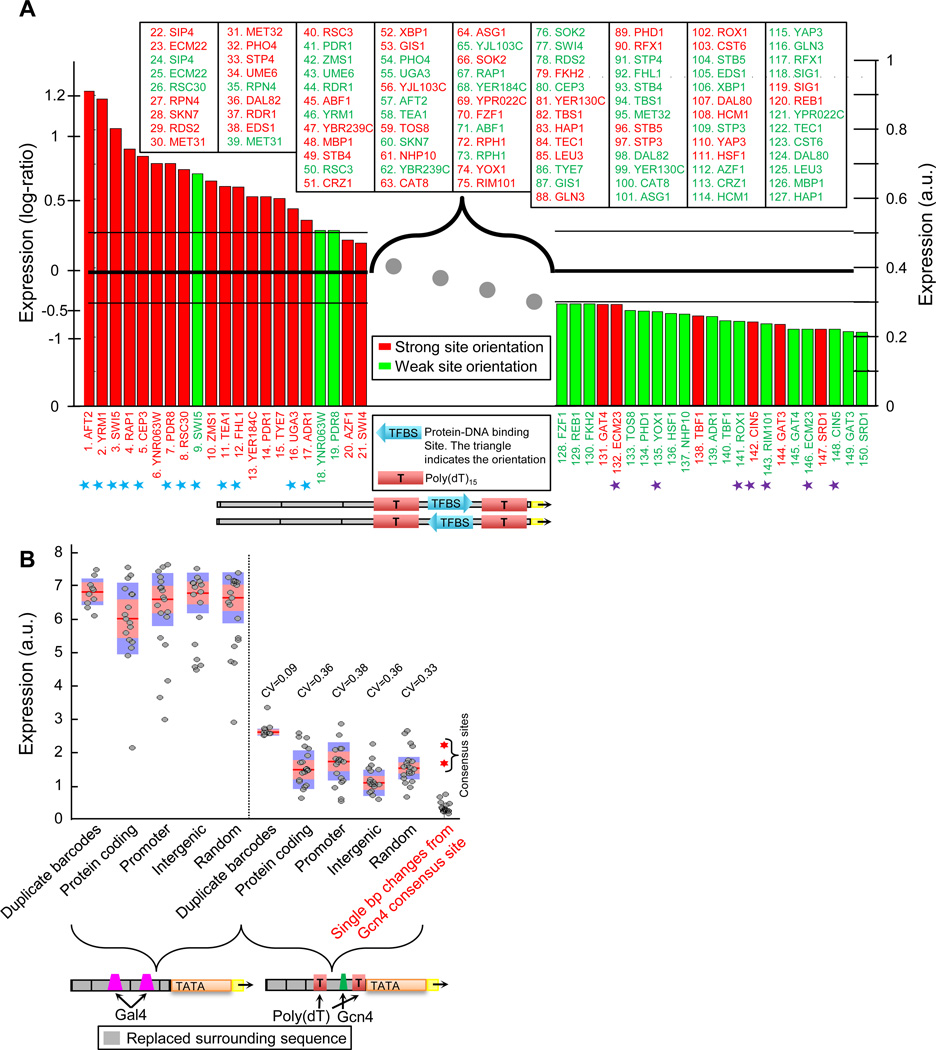

Next, we used our method to compare the activity level of 75 different yeast TFs, by separately planting their published consensus sites20 within the same promoter and in the two possible orientations. Such a set compares TF activity by the expression that their sites induce in the same promoter context and growth condition, and provides an alternative to comparisons based on protein abundance21 and cellular localization22 that do not capture the dependence of TF activity on parameters such as post-translational modification state and co-factor activity.

Of the tested TF sites, 53% had expression level comparable to a null promoter with no site, suggesting that at least in our setting, these sites have little ability to affect expression on their own (Fig. 2A). Of the remaining sites, 24% and 23% had higher and lower expression than the null promoter, respectively, and their cognate TFs correspond to known activators (e.g., Rap123, Aft224) and repressors (e.g., Rim10125, Cin526), respectively, validating our assay for profiling TF activity. Notably, for some of these sites, our results provide the first direct test of their in vivo activity, thereby suggesting novel regulatory roles for their cognate TFs. For example, Ecm23, whose site we identified as repressing, was reported as a repressor of pseudohyphal growth27 and deletion of YER184C, whose site we identified as activating, prevents growth on glycerol or lactate28 but the activity of these TFs’ sites was not experimentally tested (Fig. 2A). Finally, by comparing the expression of the two tested orientations of each TF site, we obtained a measure of site orientation effect, and found significant such effects for only 6 (8%) TFs (P<0.05, 1.9–2.3 fold, Fig. S5). Among these 6 TFs was Rap1, consistent with mutational analysis29 and with an orientation bias for its sites in Rap1 target promoters30.

Figure 2. Profiling the activity of most yeast transcription factors.

(A) Consensus binding sites for 75 yeast transcription factors were separately inserted in their two possible orientations at the same position within a fixed promoter context (bottom illustration). Shown is a ranking of the resulting expression levels for each promoter, with the two site orientations of each TF colored red and green depending on whether they correspond to the orientation with higher or lower expression, respectively. For brevity, individual measurements for promoters with intermediate expression levels are not given (TF sites and their internal ranking are indicated in the box). Cyan and purple asterisks correspond to TFs with literature-reported activating or repressive roles, respectively. A horizontal black line marks the expression of the same fixed promoter above but without any known TF binding site, and the two thin lines above and below this line mark a confidence level of 30% around it. Y-axes show both the absolute expression levels (right axis) and the (log) ratio of expression to that of a promoter without a binding site (left axis). (B) Surrounding sequence has a significant yet limited effect on expression of regulatory elements and is similar for different types of surrounding sequences. Shown are the expression levels of promoters in which a regulatory block consisting of two Gal4 binding sites (left five columns) or of a single Gcn4 binding site flanked by two nucleosome disfavoring sequences (right five columns) were placed at the same position within different types of surrounding sequence contexts. The sequence contexts were chosen randomly from yeast protein coding regions (20 sequences), yeast promoters (20 sequences), yeast intergenic regions that are not promoters (20 sequences), and 20 sequences were generated randomly using the same G/C content as that of yeast promoters (G/C=40%, 20 sequences). For comparison, each regulatory block was also placed 20 different times within the same promoter but each time with a different barcode (columns 1 and 6). For each set, shown are the individual promoter expression levels (gray dots), and their median (red line), standard error (orange bar), and standard deviation (blue bar), and coefficient of variation (CV, standard deviation divided by the mean). As another comparison for the effect of surrounding sequence on expression, the rightmost column shows the expression levels of all 21 promoters from Fig. S6A in which we mutated a single basepair in the Gcn4 consensus site (gray points), along with the expression of a promoter that contains the consensus or its reverse complement (red points).

Taken together, although these results may depend on the tested promoter context or growth condition, they directly compare the activity of many TF sites, suggest novel regulatory roles for several TFs, and quantify the transcriptional effect of site orientation.

The effect of binding site affinity

Despite its importance, systematic assays of the effect of TF site affinity on expression are not available. We suggest that our method can perform such assays, by comparing the expression of promoters in which only the TF site is systematically varied. To demonstrate this, we separately planted the consensus site of three different TFs within the same promoter background, along with all possible single basepair mutations from that consensus, and many mutations to combinations of two and three basepairs. For Gcn4, the expression of both the consensus and its reverse complement were >3-fold than all other site variants, which themselves generated a continuous range of expression levels (Fig. S6A). Notably, we found good agreement (R2=0.93, Fig. S6B) between these expression levels and those predicted by the in vitro Gcn4 site affinities31, which persisted even at the lower expression and affinity levels, suggesting that even for weak sites, affinity differences are manifested in vivo. Sites for the two other TFs, Fhl1 and Leu3, had overall lower expression levels than Gcn4 and their measurements were thus noisier. Nevertheless, their data also exhibited significant correlation to in vitro measurements (R=0.21–0.28), and for Fhl1, our measurements provide the first comprehensive in vivo validation of its in vitro binding specificities20 (Fig. S7). These results support the use of our method for assaying the effect of site affinity in vivo, and suggest that in vitro site affinity assays31–33 provide a reliable measure of this effect across a broad range of affinities.

The effect of surrounding sequence on the activity of regulatory elements

As the converse of varying a TF site within a fixed promoter background, we next tested the effect of varying the promoter background on the expression induced by two blocks of regulatory elements, one consisting of two Gal4 sites and another of a single Gcn4 site flanked by two poly(dA:dT) tracts. We separately embedded each block at a fixed position within 80 different surrounding sequences, selected randomly from yeast protein coding regions (20 sequences), yeast promoters (20), and non-promoter intergenic yeast regions (20), and 20 sequences were generated randomly using the ~40% G/C content of native yeast promoters. The expression variability of each set of 20 promoters (coefficient of variation, CV=0.2–0.38) was greater than the variability obtained when placing these same regulatory blocks in 20 promoters that differ only by their barcode (CV=0.06–0.09, Fig. 2B). However, although significant, these context effects were smaller than the effect of single basepair mutations in the TF site and nearly all of the 80 promoters with two Gal4 sites were markedly higher than all 80 promoters with a single Gcn4 site (Fig. 2B). Notably, for both regulatory blocks, the distribution of expression levels was similar between the four different types of contexts. Together, these results suggest that sequences that surround regulatory elements can have significant effects on expression, but the identity of the TF sites may be a stronger determinant of the resulting expression levels.

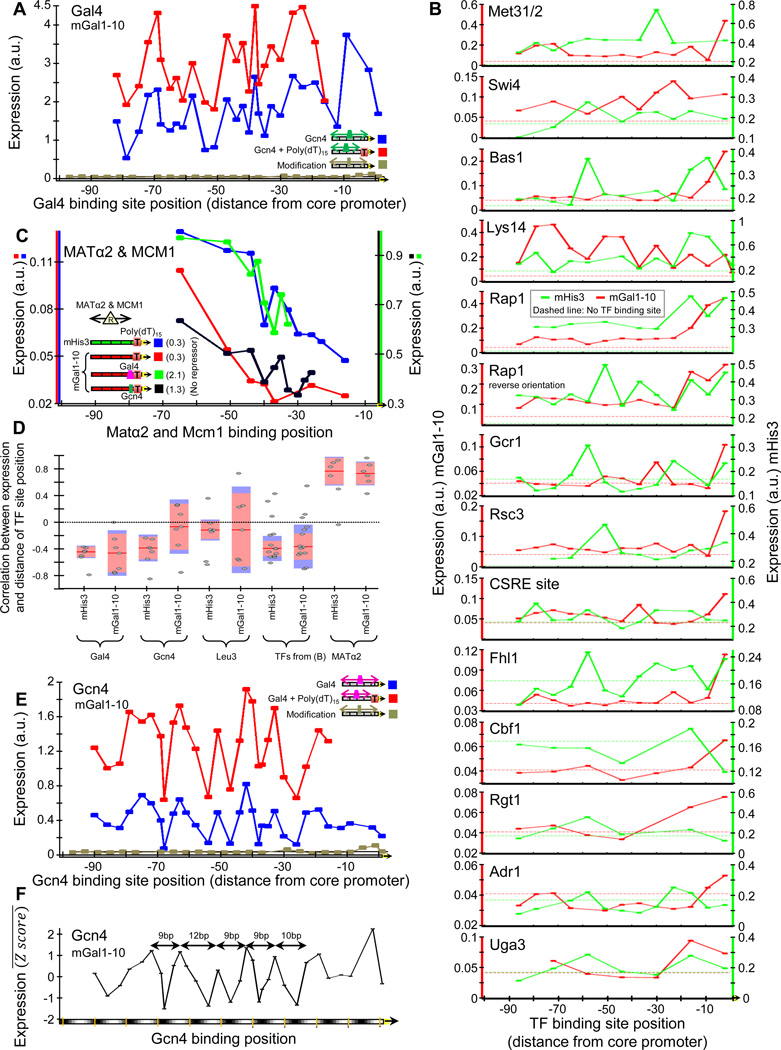

The effect of binding site location

Next, we utilized our ability to fully design and accurately measure promoters to systematically test the effect of binding site location on expression. We selected 3 TFs and separately inserted their consensus sites in 16 different promoter contexts while varying the site location in each context at 1–4bp increments. For 14 additional TFs, we designed similar constructs but at 7bp increments. Notably, for most TFs and contexts, expression level and site location were related by a jagged function specific to the combination of the TF site and context, such that even small 1–7bp changes in site location had major effects (Fig. 3Fig. S8–9). These effects are only partly explained by noise in our experiment (Fig. S10), promoter barcodes (Fig. S11), removal of sequences in the original promoter that are replaced when TF sites are inserted (Fig. S12), or the basepairs flanking the inserted sites.

Figure 3. The effect of binding site location on expression.

(A) Expression depends on Gal4 site location. Shown are the expression levels of promoters in which we inserted the consensus site for Gal4 at different locations (in 3–4bp increments) within two fixed promoter backgrounds (red and blue lines, backgrounds differ by the presence of a poly(dA:dT) tract). Points correspond to the location in the promoter of the rightmost basepair of the Gal4 site. For comparison, shown are the expression levels of the original promoter with no Gal4 sites (black line) and of promoters (gray) in which random mutations of 3bp each time were performed across the non-poly(dA:dT) promoter, indicating that the effect of changing the location of Gal4 sites is not due to removal of the original promoter sequence. (B) Same as (A), for 14 additional TFs whose sites we varied at 7bp increments in two different promoter backgrounds. (C) The effect of repressor sites decays with their distance from the core promoter. For the Matα2p-Mcm1p repressor complex, shown are four sets of promoters in which we modified the location of its site along the promoter, where the four sets differ by the presence of poly(dA:dT) tracts and sites for the transcriptional activators Gcn4 and Gal4. For each of the four sets, the expression of the promoter without the repressor site is indicated in the inset legend and is higher than all promoters that contain the repressor site, as expected. (D) The effect of TFs on expression shows a general trend of decay with the distance between their sites and the core promoter. For each set of promoters in which we changed the location of a TF binding site within the same promoter background, we computed the correlation between the expression at each location and the distance of the TF site at that location from the core promoter. Shown are the resulting correlations, where for Gal4, Gcn4, Leu3, and Matα2p-Mcm1p, each column groups together correlations of promoter sets for the same TF in backgrounds that differ in the presence of poly(dA:dT) tracts and for all other TFs that were each done in two distinct promoter backgrounds, correlations are grouped by backgrounds. For each column, the median (red line), standard error (orange bar), and standard deviation (blue bar) of the correlations are shown. Note the trend of negative correlation between expression and site distance for all TFs except the repressor Matα2p- Mcm1p for which there is a positive correlation. (E) Expression changes as a ~10bp periodic function of Gcn4 site location. Same as (A), but for Gcn4 sites. (F) Same as (E), but here each point corresponds to the average expression level of 8 sets of promotes in which we changed the location of the Gcn4 site, where the 8 different sets differ in the location of a poly(dA:dT) tract of length 15bp. To normalize the expression levels across the 8 different sets, expression is shown as a robust Z-score, by subtracting the median and dividing by the standard deviation of expression level differences from the median. Note the ~10bp periodicity of expression observed over 5 periods (distances between neighboring peaks of expression level are indicated, with x-axis colors matching 10.5bp periodicity).

Beyond these jagged relationships, we found an overall trend of lower expression, on average, as activator sites are further away from the gene start, and an opposite trend for repressor sites (Fig. 3 C,D, S9). We did not find a clear trend in the effect of the repressor site when its location was held fixed and the location of an activator site was changed (Fig. S13). Strikingly, for Gcn4, one of the three TFs whose sites we varied at 1–4bp increments, expression level and site location were related by a periodic function that persisted over 6 consecutive peaks and whose period is ~10bp, roughly matching the DNA helical repeat (Fig. 3E). This periodicity was significant in only one of the two promoter backgrounds in which we varied Gcn4 site locations but in this background, we observed it in seven different variants of this background (Fig. 3F, S14). To test whether this finding can improve our ability to predict expression from sequence, we extended a thermodynamic model for transcriptional regulation to include an interaction energy term between Gcn4 and polymerase that depends on the helical phase, and found that this model indeed improves expression predictions of held-out promoters (Fig. S15).

We note that even if similar periodicities exist for the other 14 tested TFs, the 7bp site location increments that we designed for these TFs prohibit their detection.

Taken together, our results demonstrate a surprising dependency of expression on TF site location, such that even small 1–7bp changes can have major effects. Although expression and site location are related by a jagged function specific to the TF and promoter background combination, we found an overall trend of decay of the effect of TF sites as their distance from the gene start increases, even within the ~100bp region that could be examined using our approach. However, this trend is relatively weak and does not explain most of the effect of site location on expression.

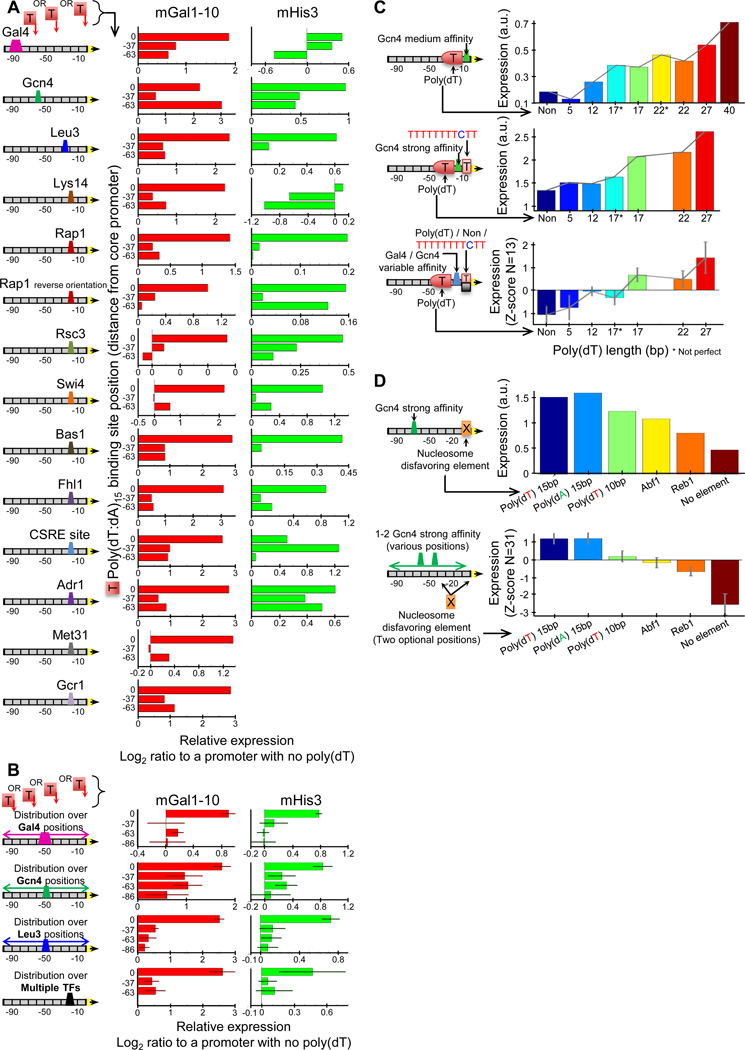

The effect of nucleosome disfavoring sequences

Previous studies showed that placing nucleosome disfavoring sequences, specifically poly(dA:dT) tracts, next to TF sites significantly affects expression, in a manner that depends on the length, composition, and location of the tract and is mostly positive regardless of TF identity8, 34. However, since these findings were derived from dozens of variants of the same promoter background, we sought to test whether they generalize more broadly using the larger scale of promoters that can be examined with our method. Notably, using 777 promoters in which we separately inserted consensus sites for 14 TFs in two different promoter backgrounds while varying either the site location or the location, length, and orientation of the poly(dA:dT) tract, we found effects that were consistent with, and thus considerably generalize, previous findings8, 34 (Fig. 4A–C, S16).

Figure 4. The effect of nucleosome disfavoring sequences on expression.

(A) Addition of nucleosome disfavoring sequences near TF sites increases expression. Shown are expression levels for 14 sets of promoters in which a poly(dA:dT) tract of length 15bp was separately inserted at various locations within two promoter backgrounds that each contain a TF binding site at some fixed position. For each set, each bar corresponds to the (log) ratio between the expression of a promoter that contains the poly(dA:dT) tract and the expression of the same promoter in which the poly(dA:dT) is not present. (B) Same as (A), but here each bar shows the median and standard error of the expression obtained for promoters in which the poly(dA:dT) was at a fixed position and the location of the TF site varied. The fourth row (‘multiple TFs’) represents the average of the last 11 TFs from (A). (C) The stimulatory effect of poly(dA:dT) tracts increases with their length. Shown are expression levels for two sets of promoters (first two rows) in which sites with different affinities for Gcn4 were separately placed at a fixed location within different promoter backgrounds that contained poly(dA:dT) tracts of varying lengths at a fixed promoter location. Also shown (bottom row) is the median and standard error of expression for promoters with various TF sites and site affinities. (D) The stimulatory effect of poly(dA:dT) tracts can be greater than that of the general TF activators Reb1p and Abf1p. Shown is the expression of promoters in which different elements (no element, Reb1p site, Abf1p site, 10bp poly(dA:dT) tract, 15bp tract, 15bp tract flipped in its orientation) were placed at the same location within a promoter background that contains a consensus Gcn4 site at a fixed location (top row). For each element, also shown is the average and standard deviation of expression of promoters in which it was inserted at two possible positions within 31 different promoter backgrounds that differ in the number and location of Gcn4 sites and the surrounding sequence (bottom row). To normalize the expression levels across the promoters of each set, expression is shown as a robust Z-score, by subtracting the median and dividing by the standard deviation of distances from the median.

We also explored a novel aspect of poly(dA:dT) tracts by comparing the magnitude of their effect on expression to that of Reb1 and Abf1 sites, since the high nucleosome depletion of these sites in vivo was suggested to result from the own action of these TFs15. Notably, although adding Reb1 and Abf1 sites results in significantly higher expression, the effect is comparable to that of adding a 10bp poly(dA:dT) tract and significantly less than that of a 15bp tract (P<10−6, Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the yeast genome can enhance promoter expression to similar levels by depleting nucleosomes with either the cis-regulatory mechanism of poly(dA:dT) tracts or the trans-regulatory mechanism of sites for general TFs such as Reb1 and Abf1.

The effect of binding site number

Next, we utilized our ability to design promoters with many combinations of TF sites to systematically test the dependence of expression on the number of sites. We selected two promoter contexts and in each, separately inserted the consensus site for Gcn4 and Gal4 in all 27=128 and 25=32 possible combinations of sites at seven and five predefined locations, respectively. Notably, we found a clear relationship between the number of sites and the average expression of promoters with that number of sites for both TFs in both contexts, which accurately fits a logistic function (R2=0.99, Fig. 5A,B). In all cases, expression increases with each of the first 3–4 sites but then mostly saturates.

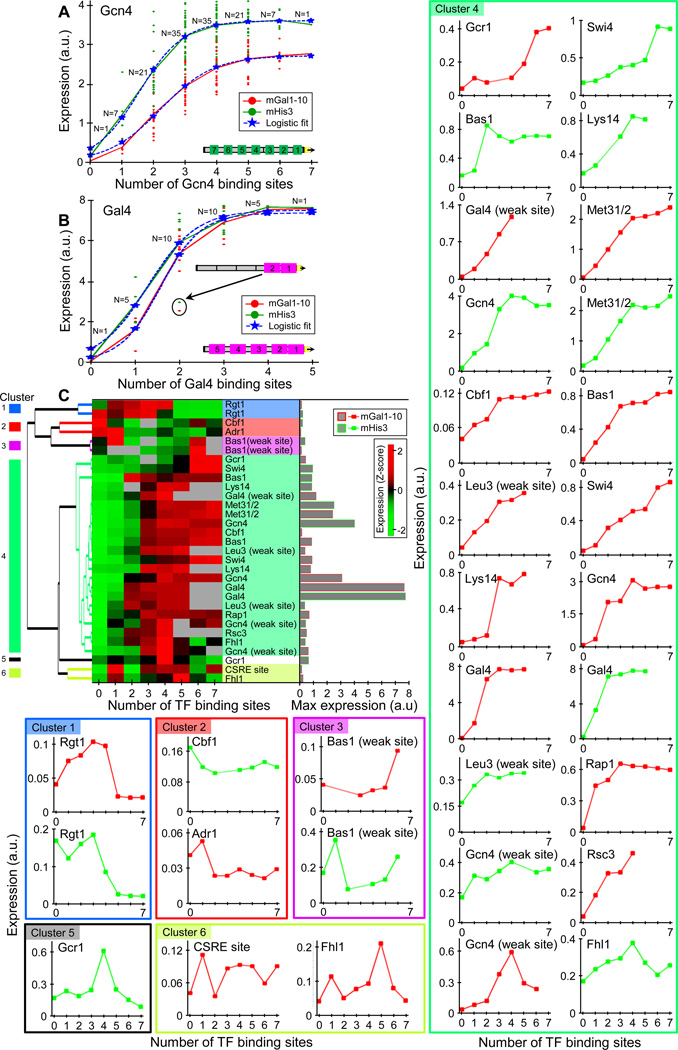

Figure 5. The effect of binding site number on expression.

(A) Expression level is, on average, a monotonic function of Gcn4 sites that mostly saturates at 3–4 sites. Within two different promoter backgrounds, we separately inserted Gcn4 sites in all 27=128 possible combinations of sites at seven predefined locations within the promoter. For each background, shown are the individual promoter expression levels and mean level of all promoters that have k Gcn4 sites, for k=0, 1, 2, …, 7. Also shown is a fit of a logistic function for each background. (B) Same as (A), but for all 25=32 possible combinations of Gal4 sites at five predefined promoter locations. The outlier promoter in terms of expression level in which the two Gal4 sites closest to the core promoter were both added is indicated. These two sites were added at a distance of 1bp as opposed to a 5bp distance between all other adjacent sites, thus suggesting steric hindrance between Gal4 sites at this distance. (C) For many TFs, expression is generally a monotonically increasing function of the number of sites. Shown is a hierarchical clustering and heatmap of the expression profile of 31 sets of promoters where in each set, the same TF site was inserted in k copies within the same promoter background, for k=0,1,2,…,7. Within the heatmap, expression profiles of each TF site were normalized to have mean zero and standard deviation one. The 31 sets correspond to 18 different TF sites (15 different TFs, as 3 TFs have two site variants differing in their affinity) with each site inserted in two different promoter backgrounds. Also shown (right bars) is the absolute expression level of the strongest promoter for each TF site, demonstrating that the expression level at saturation differed greatly among the different TF sites. We defined six clusters from the hierarchical clustering based on the correlations between the expression profiles of the various TFs, and the expression profiles for the individual TF sites of every cluster are shown within colored boxes (right and bottom).

Despite this close fit of the average expression of a given number of sites to a logistic function, individual promoters with specific combinations of site locations deviate from the expression predicted for them by this logistic model. Part of this deviation likely stems from the different effects that sites have at different promoter locations, while another likely results from non-additive interactions between pairs of sites, predominantly from interactions between adjacent sites (Fig. S17, S18). Notably, our results suggest that two Gal4 molecules sterically occlude each other in binding to two sites whose ends are one basepair apart, and that Gcn4 may exhibit similar albeit weaker behavior when its site ends are 5bp apart (Fig. S19).

We extended the above set to 13 additional TFs but at lower resolution, whereby for each TF, we generated promoters with zero, one, and up to five (1 TFs) or seven (12 TFs) sites in increments of one site and in two different contexts. At this lower resolution, the results are more sensitive to location-specific site contributions, since there is only one promoter for each TF in every context and site number combination. Nevertheless, clear trends were apparent, whereby for most TFs, expression largely increases with more sites, mostly saturating ~3–4 sites (Fig. 5C, S20). One notable exception is Rgt1, for which expression is a non-monotonic function of site number, typically increasing with the first three sites but then dramatically decreasing at 4 or more sites (Fig. 5C, S21A). This suggests that Rgt1 is a potent repressor only with >4 sites, consistent with a study of one native Rgt1 target35. For the Matα2p-Mcm1p repressor, we also found stronger repression with more sites, although here repression is already evident with one site (Fig. S21B).

Thus, we found a clear relationship between expression and the number of activator sites that accurately fits a logistic function, whereby expression increases monotonically with more sites and mostly saturates ~3–4 sites. Notably, the expression level at saturation differs greatly among TFs, and with one exception (Met31/2), all of the promoters for the 13 TFs tested, including those with 7 sites, have much lower expression than that of a promoter with a single Gal4 site or 1–2 Gcn4 sites (Fig. 5C). This suggests that in our growth condition and promoter backgrounds, the TF identity is more important for achieving high expression levels than site number.

Comparing the effect of different types of sequence changes

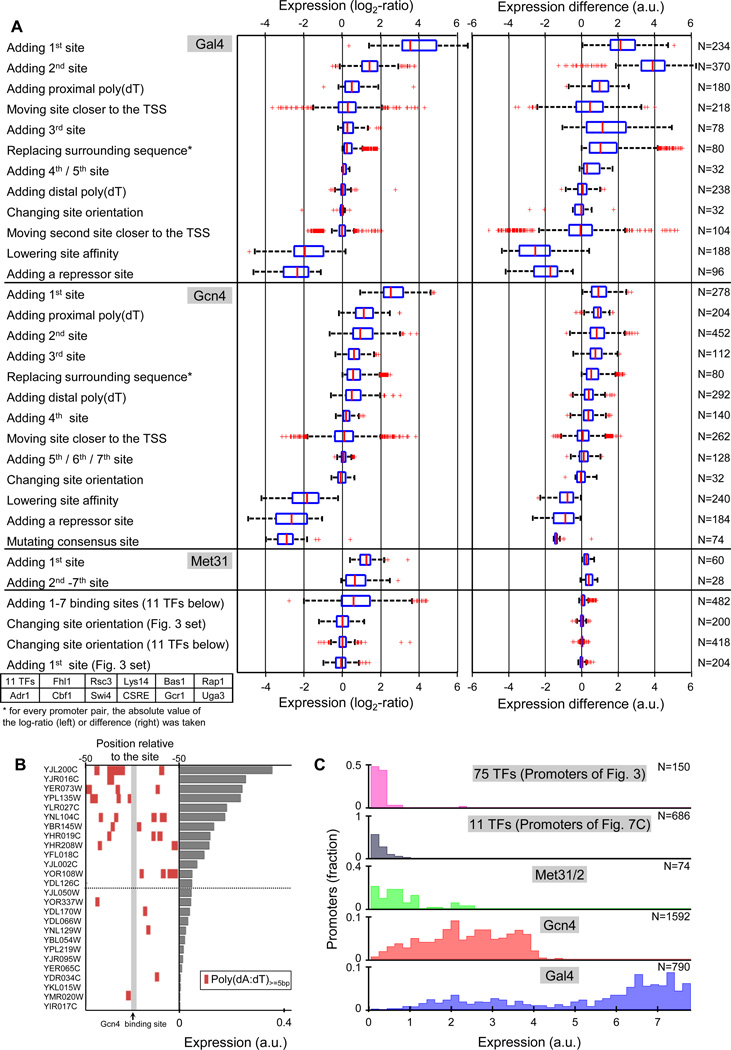

Finally, to obtain a high-level view of our library, we partitioned the 6500 promoters into sets, such that each represents changes to the same type of regulatory element. Within Gal4 and Gcn4 regulated promoters, we found coherent and expected behavior, whereby in most cases, adding sites for these TFs or adding poly(dA:dT) tracts increased expression, whereas lowering site affinity or adding repressor sites decreased expression (Fig. 6A). In contrast, increasing the distance of Gal4 or Gcn4 sites had stimulatory effects in some cases and inhibitory effects in others. The different types of sequence changes also exhibited a fairly robust ranking in the magnitude of their effect, with the largest effect coming from addition of the first 1–2 Gal4/Gcn4 sites or of a proximal poly(dA:dT) tract to a promoter that contains at least one Gal4/Gcn4 site (Fig. 6A). To test the applicability of one of these rules in endogenous promoters, we generated fluorescent reporter strains for 26 yeast promoters with a consensus Gcn4 site, and indeed found a significant enrichment of poly(dA:dT) tracts in the more highly expressed promoters (P<0.003, Fig. 6B)

Figure 6. Comparing the effect of different types of sequence changes.

(A) Shown are the effects on expression of different types of sequence changes, either as the change in the (log) ratio (left panel) or absolute levels (right panel) of expression. In every row, the boxplot summarizes the effect of a particular type of sequence change (indicated by the text on the left), where each point in the boxplots compares the expression of a promoter in which the change was done to the expression of the same promoter without the change. The first block of changes (12 types) represents changes to Gal4 sites or promoter containing Gal4 sites, the second block to Gcn4 (13 types), the third to Met31 (2 types), and the final block (4 types) pulls together changes to 11 different TFs. The number of promoters used in each boxplot is indicated on the right. In each block, rows are sorted by their effect on the ratio of expression (left panel). (B) Native yeast promoters with poly(dA:dT) tracts near Gcn4 consensus sites have higher expression. Shown is the expression level (right bars, promoters are sorted by expression) of 26 native yeast promoters that contain a consensus Gcn4 site, along with the distribution of poly(dA:dT) tracts that are at least 5bp in length in the 100bp surrounding the Gcn4 site (left heatmap). Each promoter was measured by the fluorescence of a strain in which it was fused to a YFP reporter as described in Zeevi et al.19. Note the enrichment of poly(dA:dT) in the more highly expressed promoters. (C) The expression levels of promoters with Gal4 or Gcn4 sites is much higher than that of all promoters with sites for other TFs. Shown is the distribution of expression levels for five different promoter sets, representing promoters with single sites for 75 different TFs (first row); promoters with various manipulations to sites for 11 different TFs, including promoters with up to seven sites for each of these TFs (second row); all of the promoters that contain only Met31/2 sites (third row), Gcn4 sites (fourth row), and Gal4 sites (fifth row). The last three rows include all of the manipulations that we did to promoters with sites for these TFs.

Notably, the expression of all 836 promoters in which we manipulated sites for 75 TFs other than Gal4 and Gcn4 was dramatically lower than the vast majority of 602 promoters that contain just a single Gal4 or Gcn4 site (Fig. 6A,C). These 836 promoters represent a variety of changes to the location and orientation of TF sites and for 11 TFs, they include promoters with one, two, and even seven sites. Although Gal4 and Gcn4 are activated in our chosen growth condition (galactose medium starved for amino acids), the magnitude of the expression difference is surprising. The reason for this finding is unclear. Possible explanations include higher amounts of active Gal4 and Gcn4 molecules, stronger activation domains, or that the tested promoter contexts are less suitable for the other TFs. Regardless of the reason, our results suggest that at least in our tested condition and contexts, TF identity is the most important factor in achieving high expression levels.

Discussion

In summary, we presented a high-throughput method for measuring the expression of thousands of fully designed promoters within a single experiment and with accuracy comparable to that obtained when promoters are constructed and measured individually. We applied our method to study how expression depends on various parameters such as the identity, number, affinity, and location of TF binding sites, representing the first large-scale systematic testing of the effects of these parameters. For several types of sequence manipulations, our data reinforce previous results or support hypotheses that have arisen from smaller scale studies (Supp. Note 1). In other cases, the effects are more surprising and their mechanistic basis is unclear, raising interesting open questions for further research. For example, we found that changing a TF site location by even a few basepairs typically exerts large effects. As another example, we were surprised by the dramatically higher expression that most of the 602 promoters with even a single Gal4 or Gcn4 site have compared to that of all ~700 promoters that contained sites for 11 other TFs. Notably, these ~700 promoters include nucleosome disfavoring sequences and up to seven sites for each of these TFs. Finally, even when the qualitative effects match our expectation, the next challenge is to mechanistically explain the quantitative magnitude of the effects.

Despite the above insights, our method has several limitations, the most notable of which stems from the limited ~100bp length of the promoter region that we could vary (Supp. Note 2).

For decades, researchers have searched for a regulatory code that translates DNA sequence into expression level. The fact that several types of sequence changes that we performed have predictable effects on expression that hold across many contexts and TFs suggests that such a general code may indeed exist, but from the many unexplained effects that we found it is also clear that we are still far from its deciphering. The ability to carefully design large-scale promoter libraries should prove useful for advancing our understanding, eventually leading to quantitative predictive models of transcriptional regulation. It will also be exciting to apply similar strategies to study the effect that other regulatory layers have on gene expression and on other biological phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Chiang DY, Nix DA, Shultzaberger RK, Gasch AP, Eisen MB. Flexible promoter architecture requirements for coactivator recruitment. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ligr M, Siddharthan R, Cross FR, Siggia ED. Gene expression from random libraries of yeast promoters. Genetics. 2006;172:2113–2122. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinkhabwala A, Guet CC. Uncovering cis regulatory codes using synthetic promoter shuffling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gertz J, Siggia ED, Cohen BA. Analysis of combinatorial cis-regulation in synthetic and genomic promoters. Nature. 2009;457:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature07521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox RS, 3rd, Surette MG, Elowitz MB. Programming gene expression with combinatorial promoters. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:145. doi: 10.1038/msb4100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinney JB, Murugan A, Callan CG, Jr, Cox EC. Using deep sequencing to characterize the biophysical mechanism of a transcriptional regulatory sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9158–9163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004290107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giniger E, Ptashne M. Cooperative DNA binding of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:382–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer V, Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. Embo J. 1995;14:2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam FH, Steger DJ, O'Shea EK. Chromatin decouples promoter threshold from dynamic range. Nature. 2008;453:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature06867.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy KF, Balazsi G, Collins JJ. Combinatorial promoter design for engineering noisy gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12726–12731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patwardhan RP, et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA regulatory elements by synthetic saturation mutagenesis. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patwardhan RP, et al. Massively parallel functional dissection of mammalian enhancers in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:265–270. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melnikov A, et al. Systematic dissection and optimization of inducible enhancers in human cells using a massively parallel reporter assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:271–277. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeProust EM, et al. Synthesis of high-quality libraries of long (150mer) oligonucleotides by a novel depurination controlled process. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2522–2540. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan N, et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baliga NS. Promoter analysis by saturation mutagenesis. Biological procedures online. 2001;3:64–69. doi: 10.1251/bpo24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JD, Widom J. Poly(dA-dT) promoter elements increase the equilibrium accessibility of nucleosomal DNA target sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3830–3839. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3830-3839.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal E, Widom J. Poly(dA:dT) tracts: major determinants of nucleosome organization. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeevi D, et al. Compensation for differences in gene copy number among yeast ribosomal proteins is encoded within their promoters. Genome Res. 2011;21:2114–2128. doi: 10.1101/gr.119669.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badis G, et al. Diversity and complexity in DNA recognition by transcription factors. Science. 2009;324:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1162327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huh WK, et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, et al. Fine-structure analysis of ribosomal protein gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4853–4862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02367-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaiseau PL, Lesuisse E, Camadro JM. Aft2p, a novel iron-regulated transcription activator that modulates, with Aft1p, intracellular iron use and resistance to oxidative stress in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34221–34226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb TM, Mitchell AP. The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:677–686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.677-686.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanlon SE, Rizzo JM, Tatomer DC, Lieb JD, Buck MJ. The stress response factors Yap6, Cin5, Phd1, and Skn7 direct targeting of the conserved co-repressor Tup1-Ssn6 in S cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canizares JV, Pallotti C, Sainz-Pardo I, Iranzo M, Mormeneo S. The SRD2 gene is involved in Saccharomyces cerevisiae morphogenesis. Archives of microbiology. 2002;177:352–357. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akache B, Wu K, Turcotte B. Phenotypic analysis of genes encoding yeast zinc cluster proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2181–2190. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.10.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woudt LP, Smit AB, Mager WH, Planta RJ. Conserved sequence elements upstream of the gene encoding yeast ribosomal protein L25 are involved in transcription activation. Embo J. 1986;5:1037–1040. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieb JD, Liu X, Botstein D, Brown PO. Promoter-specific binding of Rap1 revealed by genome-wide maps of protein-DNA association. Nat Genet. 2001;28:327–334. doi: 10.1038/ng569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutiu R, et al. Direct measurement of DNA affinity landscapes on a high-throughput sequencing instrument. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. A systems approach to measuring the binding energy landscapes of transcription factors. Science. 2007;315:233–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1131007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulyk ML, Gentalen E, Lockhart DJ, Church GM. Quantifying DNA-protein interactions by double-stranded DNA arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:573–577. doi: 10.1038/9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raveh-Sadka T, et al. Manipulating Nucleosome Disfavoring Sequences Allows Fine-Tune Regulation of Gene Expression in Yeast. doi: 10.1038/ng.2305. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JH, Polish J, Johnston M. Specificity and regulation of DNA binding by the yeast glucose transporter gene repressor Rgt1. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5208–5216. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5208-5216.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karolchik D, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:51–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu C, et al. High-resolution DNA binding specificity analysis of yeast transcription factors. Genome Res. 2009;19:556–566. doi: 10.1101/gr.090233.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleary MA, et al. Production of complex nucleic acid libraries using highly parallel in situ oligonucleotide synthesis. Nat Methods. 2004;1:241–248. doi: 10.1038/nmeth724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheff MA, Thorn KS. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2004;21:661–670. doi: 10.1002/yea.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breslow DK, et al. A comprehensive strategy enabling high-resolution functional analysis of the yeast genome. Nat Methods. 2008;5:711–718. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Tukey JW. Understanding robust and exploratory data anlysis. Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.