Abstract

Pre-portioned entrées are commonly consumed to help control portion size and limit energy intake. The influence of entrée characteristics on energy intake, however, has not been well studied. We determined how the effects of energy content and energy density (ED, kcal/g) of pre-portioned entrées combine to influence daily energy intake. In a crossover design, 68 non-dieting adults (28 men and 40 women) were provided with breakfast, lunch, and dinner on one day a week for four weeks. Each meal included a compulsory, manipulated pre-portioned entrée followed by a variety of unmanipulated discretionary foods that were consumed ad libitum. Across conditions, the entrées were varied in both energy content and ED between a standard level (100%) and a reduced level (64%). Results showed that in men, decreases in the energy content and ED of pre-portioned entrées acted independently and added together to reduce daily energy intake (both P<0.01). Simultaneously decreasing the energy content and ED reduced total energy intake in men by 16% (445±47 kcal/d; P <0.0001). In women, the entrée factors also had independent effects on energy intake at breakfast and lunch, but at dinner and for the entire day the effects depended on the interaction of the two factors (P <0.01). Simultaneously decreasing the energy content and ED reduced daily energy intake in women by 14% (289±35 kcal/d; P<0.0001). Both the energy content and ED of pre-portioned entrées affect daily energy intake and could influence the effectiveness of such foods for weight management.

INTRODUCTION

Effective strategies are needed to help individuals manage their food intake in an environment filled with large portions of energy-dense foods. One strategy shown to be useful in moderating energy intake and managing body weight is the consumption of pre-portioned foods, such as liquid meal replacements and solid pre-portioned entrées (1–9). Although most research has investigated liquid meal replacements, several studies examined the consumption of solid pre-portioned entrées over multiple weeks and showed that participants achieved greater weight loss using the entrées than with self-selected diets (6–9). These studies, however, provided little data on how the characteristics of pre-portioned entrées influence satiety and energy intake. For example, if pre-portioned entrées are too restricted in energy content, they may not provide a satisfying portion of food; as a result, individuals may remain hungry and more likely to consume excessive energy from the wide assortment of foods that are readily available. The present study investigated how changes in the energy content and energy density (ED) of pre-portioned entrées influence satiety and energy intake over a day.

One approach for investigating the effects of pre-portioned entrées is to provide manipulated compulsory entrées followed by a variety of discretionary foods that allow compensation for differences in satiety (10). Most research using this type of preloading paradigm has tested foods that are typically eaten as a first course. Several studies have found that the energy content of a preload such as yogurt or soup influences satiety and energy intake at the following test meal (11–13). Other research has shown that satiety is also affected by the ED of preloads of soup or salad (14–16). For example, consumption of a large, low-ED salad reduced test meal energy intake compared to an equicaloric salad higher in ED and smaller in portion size (16). A few preloading studies have tested foods that are typically consumed as the main dish of a meal. In one study, manipulated entrées were served at three meals per day and additional discretionary foods were offered; it was found that daily energy intake was influenced by varying the ED, but not the fat content, of the equicaloric entrées (17). More information is needed about how entrées can be modified strategically to reduce energy intake at meals.

The objective of the present study was to use pre-portioned entrées in a preloading design to examine the effects of two food characteristics known to affect satiety: energy content and ED. We hypothesized that reductions in the energy content and ED of the entrées would act independently and add together to reduce daily energy intake. Changing the energy content and ED of foods leads to differences in portion size because these three food characteristics are directly related. In order to control the effects of portion size, in two of the experimental conditions entrée portions were matched while both energy content and ED were manipulated. We predicted that simultaneously reducing the energy content and ED of entrées with the same portion size would decrease energy intake over the day.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Study design

This experiment used a crossover design with repeated measures within subjects. One day a week for four weeks, participants were provided with all of their foods and beverages for breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals. Across test days, the entrée at each meal was varied in both energy content and ED between a standard level (100%) and a reduced level (64% of the standard). Following consumption of the compulsory entrée, a variety of unmanipulated discretionary foods was served for ad libitum consumption. For both the compulsory entrées and discretionary foods, women were served 70% of the amounts served to men. The order of experimental conditions was counterbalanced across the subjects.

Subjects

Men and women aged 20 to 45 years were recruited for the study through advertisements in newspapers, flyers, and campus electronic newsletters. Potential subjects were interviewed by telephone to determine whether they met the initial study criteria, including that they regularly ate three meals per day, did not smoke, did not have any food allergies or restrictions, were not athletes in training, were not dieting, were not taking medications that would affect appetite, and were willing to consume the foods served in the test meals.

Potential subjects who met the initial study criteria came to the laboratory to have their height and weight measured (model 707; Seca Corp., Hanover, MD, USA) and to rate the taste of food samples, including the entrées that were served in the study. The following questionnaires were completed: a demographic and health questionnaire; the Zung Self-Rating Scale (18), which evaluates symptoms of depression; the Eating Attitudes Test (19), which assesses indicators of disordered eating; and the Eating Inventory (20), which measures dietary restraint, disinhibition, and tendency toward hunger. Exclusion criteria included a taste rating for any entrée sample ≤ 30 mm on a 100-mm scale; a score ≥ 40 on the Zung scale; or a score ≥ 20 on the Eating Attitudes Test. Subjects were also excluded if they reported known health problems or had not maintained their weight within 4.5 kg (10 lb) during the 6 months before the start of the study.

The sample size for the experiment was estimated using data from previous one-day studies in the laboratory. The minimum difference in daily energy intake assumed to be clinically significant was 300 kcal for men and 200 kcal for women. A power analysis estimated that a sample size of 19 men and 26 women was needed to detect this difference in daily energy intake with >80% power using a two-sided test with a significance level of 0.05.

Subjects were told the purpose of the study was to monitor eating behaviors at different meals. Subjects provided signed consent and were financially compensated for their participation. A total of 31 men and 42 women were enrolled in the study. Three men and one woman were excluded from the study for noncompliance with the study protocol. The data of one additional woman was excluded for having undue influence on the outcomes according to the procedure of Littell, et al (21). Thus, a total of 28 men and 40 women completed the study (Table 1). All aspects of the study were approved by The Pennsylvania State University Office for Research Protections.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Men (n = 28)

|

Women (n = 40)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | Range | Mean ± SEM | Range | |

| Age (y) | 26.8 ± 1.1 | 20–41 | 27.6 ± 1.1 | 20–43 |

| Height (m) | 1.77 ± 0.01 | 1.7–1.9 | 1.65 ± 0.01a | 1.5–1.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.9 ± 2.0 | 62–107 | 63.5 ± 1.5a | 49–91 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 0.6 | 20–33 | 23.3 ± 0.6a | 19–38 |

| Energy requirement (kcal/d)1 | 2831 ± 38 | 2464–3164 | 2196 ± 24a | 1847–2546 |

| Dietary restraint score2 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 1–13 | 8.3 ± 0.7a | 1–16 |

| Disinhibition score2 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0–9 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 1–11 |

| Hunger score2 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 0–12 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 0–13 |

Foods and Meals

On each test day, participants were served breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals that included a compulsory manipulated entrée and a variety of unmanipulated discretionary foods that were consumed ad libitum. Across experimental conditions, the compulsory entrées were varied in both energy content and ED between a standard level and a reduced level. In addition, the reductions in energy content and ED were chosen so that each standard entrée was matched in portion size (weight) to the entrée of reduced energy content and reduced ED (Table 2). The entrées were selected because they could be covertly manipulated in ED and matched for palatability; the discretionary foods served at the test meal were commonly consumed items that were not varied in energy content or ED (Table 3).

Table 2.

Total energy content, weight, and energy density of compulsory entrées served in the experimental conditions

| Energy density condition | Energy content condition

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 28)

|

Women (n = 40)

|

|||

| Standard | Reduced | Standard | Reduced | |

| Standard | ||||

| Entrée energy (kcal/d) | 1570 | 1000 | 1100 | 700 |

| Entrée weight (g/d) | 980 | 615 | 690 | 430 |

| Entrée energy density (kcal/g) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Reduced | ||||

| Entrée energy (kcal/d) | 1570 | 1000 | 1100 | 700 |

| Entrée weight (g/d) | 1570 | 980 | 1100 | 690 |

| Entrée energy density (kcal/g) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 kcal and 10 grams. Bolded numbers represent the entrées matched in weight (portion size).

Table 3.

Unmanipulated discretionary foods served at each meal

| Men (n = 28)

|

Women (n = 40)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | Weight (g) | Energy (kcal) | Weight (g) | |

| Breakfast | ||||

| Mandarin oranges1 | 202 | 349 | 141 | 244 |

| Plain bagels2 | 353 | 143 | 247 | 100 |

| Condiments (cream cheese3, butter4, jelly5) | 622 | 220 | 622 | 220 |

| Lunch | ||||

| Buttered broccoli4,6 | 200 | 243 | 140 | 170 |

| Rice pilaf7 | 314 | 221 | 220 | 155 |

| Grapes | 224 | 324 | 157 | 227 |

| Chocolate chip cookies8 | 416 | 86 | 290 | 60 |

| Dinner | ||||

| Salad with sliced tomatoes | 22 | 127 | 17 | 98 |

| Assorted dressings9 | 760 | 258 | 760 | 258 |

| Croutons10 | 86 | 20 | 60 | 14 |

| Crackers8 | 345 | 71 | 243 | 50 |

| Cubed cheese8 | 344 | 86 | 240 | 60 |

| Peaches1 | 130 | 323 | 91 | 226 |

| Pound cake2 | 316 | 80 | 221 | 56 |

Independent Marketing Alliance, Houston, TX, USA

Sara Lee Corporation, Downers Grove, IL, USA

Kraft Foods North America, Inc., Glenview, IL, USA

Land O’Lakes Inc, Arden Hills, MN, USA

J.M. Smucker Company, Orrville, OH, USA

Birds Eye Foods, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA

MARS Food US, LLC, Carson, CA, USA

Kraft Foods Global, Inc., Northfield, IL, USA

T. Marzetti Company, Columbus, OH, USA

Pepperidge Farm, Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA

The standard-energy versions of the compulsory entrées were designed to provide approximately 50–60% of daily energy intake, based on nationally representative data (23); thus, women received 70% of the amount that was provided to men. The reduced-energy entrées provided ~64% of the energy in the standard entrées; the reduction was accomplished by providing a smaller portion of food. Across the entire test day, the difference in compulsory energy intake from the standard-energy and reduced-energy entrées was 567 kcal for men and 403 kcal for women. Total energy content from the compulsory entrées was distributed to provide approximately 27% of the compulsory energy at breakfast, and 36.5% of the compulsory energy at both lunch and dinner. For the discretionary foods, which were not varied in energy content and were consumed ad libitum, the amounts served to women were 70% of those served to men.

The ED of the standard entrées was 1.6 kcal/g, similar to that of commercially available portion-controlled entrées intended for non-dieters. The ED of the reduced entrées was 1.0 kcal/g, or ~64% of the standard ED; the reduction was accomplished by increasing the amount of vegetables or fruit. This ED is similar to that of commercially available portion-controlled entrées marketed for weight management. The ingredients in the entrées were adjusted to maintain approximately 15% of energy as protein, 30% of energy as fat, and 55% of energy as carbohydrate (Table 4). Thus, the reduction in ED was accomplished by increasing the water content of the entrées while maintaining the macronutrient content.

Table 4.

Composition of the manipulated entrées served at each meal

| Men (n = 28)

|

Women (n = 40)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard energy content | Reduced energy content | Standard energy content | Reduced energy content | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Standard ED | Reduced ED | Standard ED | Reduced ED | Standard ED | Reduced ED | Standard ED | Reduced ED | |

| Breakfast: Yogurt parfait | ||||||||

| Weight (g) | 272 | 426 | 173 | 272 | 190 | 299 | 120 | 190 |

| Energy (kcal) | 430 | 430 | 275 | 275 | 300 | 300 | 190 | 190 |

| Fat (g) | 14.4 | 14.3 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 6.3 | 6.2 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 63.2 | 64.2 | 40.2 | 41.1 | 43.9 | 44.8 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| Protein (g) | 16.2 | 16.6 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 11.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

| Fiber (g) | 4.0 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| Lunch: Chicken rice casserole | ||||||||

| Weight (g) | 356 | 566 | 229 | 356 | 250 | 395 | 160 | 250 |

| Energy (kcal) | 570 | 570 | 368 | 368 | 400 | 400 | 256 | 256 |

| Fat (g) | 18.9 | 18.9 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 79.7 | 81.6 | 52.4 | 54.0 | 55.6 | 57.3 | 36.3 | 34.0 |

| Protein (g) | 21.7 | 22.0 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 9.8 | 10.1 |

| Fiber (g) | 2.9 | 7.6 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 7.1 | 1.4 | 4.7 |

| Dinner: Pasta bake | ||||||||

| Weight (g) | 356 | 570 | 223 | 356 | 250 | 400 | 157 | 250 |

| Energy (kcal) | 570 | 570 | 360 | 360 | 400 | 400 | 251 | 251 |

| Fat (g) | 19.2 | 19.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 8.5 | 8.3 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 76.8 | 78.1 | 48.5 | 49.6 | 53.9 | 55.5 | 34.0 | 34.9 |

| Protein (g) | 22.0 | 21.9 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Fiber (g) | 8.0 | 11.9 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 8.4 | 3.5 | 5.2 |

ED: energy density

One liter of water was served with the discretionary foods at each meal in addition to the choice of coffee or tea with breakfast. To allow measurement of water intake, bottled water was provided for consumption outside of the laboratory between meals and could be consumed as desired up to one hour before each meal. All foods and beverages were weighed before and after meals and the amount consumed was recorded to the nearest 0.1 g. Energy and macronutrient intakes were calculated using information from food manufacturers and a standard nutrient database (24).

Procedures

Subjects were instructed to keep their food intake and activity level consistent on the day before each test day, and keep a record of this information to encourage compliance. They were also instructed to refrain from consuming alcohol within 24 hours of the test day and to refrain from eating after 10 pm the evening before each test day. During test days, subjects were instructed to consume only those foods and beverages provided by the researchers until after the dinner meal. On test days, subjects came to the laboratory at scheduled meal times and were seated in individual cubicles. Lunch was served at least 3 hours after breakfast, and dinner was served at least 4 hours after lunch.

Before each meal, participants completed a brief questionnaire asking whether they had felt ill, taken any medications, or consumed any foods or beverages not provided by the researchers since the last meal. After completing the questionnaire, participants were provided with the entrée portion of the meal and instructed to consume all of the entrée within 15 minutes. Two minutes later, the discretionary foods were served and subjects were instructed to consume as much or as little as desired. After the final meal of the study, subjects completed a discharge questionnaire to report their ideas about the purpose of the study and any differences they noticed between sessions.

Ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics

Subjects used visual analog scales (25) to rate their hunger, fullness, thirst, and nausea immediately before each test meal, before receiving the discretionary foods, and after the meal. The characteristics of the entrées were also assessed using visual analog scales. Subjects were instructed to first rate the appearance of the entrée and then take a bite and answer the remaining questions about pleasantness of taste, pleasantness of texture, and calorie content.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a mixed linear model with repeated measures (SAS System for Windows, version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The fixed effects in the model were entrée energy content and ED. Planned comparisons were also performed between the two conditions in which the entrées were matched for portion size. Because men and women were provided with different amounts of food, their data were analyzed separately. The primary outcomes for the study were discretionary food and energy intakes over the day (all three meals combined) and total food and energy intakes over the day (entrées plus discretionary foods). Secondary outcomes were food and energy intakes at each meal, dietary ED at each meal and over the day, and participant ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics. The calculation of dietary ED was determined using foods only; beverages were not included (26). Summary measures of hunger and fullness for the day were calculated from the area under the curve of the ratings across time using the trapezoid formula (27). Subject characteristics were investigated as covariates in the main statistical model. Daily energy expenditure of participants was estimated from sex, age, height, weight, and activity level (22). Results are reported as mean ± standard error and were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Energy intake

Effects of entrée energy content

In men, reductions in entrée energy content had a significant effect on energy intake for the entire day, independent of reductions in ED (Figure 1). Decreasing the energy content of the compulsory entrées resulted in a significant decrease in daily energy intake of 311 ± 37 kcal or 12% (P < 0.002; Table 5). Energy intake from discretionary foods increased by 256 ± 37 kcal after men consumed the reduced-energy entrées rather than the standard-energy entrées (P < 0.003). This increase in discretionary energy intake, however, was insufficient to fully compensate for the 567 kcal reduction in energy content from the entrées. Analysis of each meal showed that in men, the effect of energy content on discretionary and total energy intake was significant at breakfast, lunch, and dinner (P < 0.05).

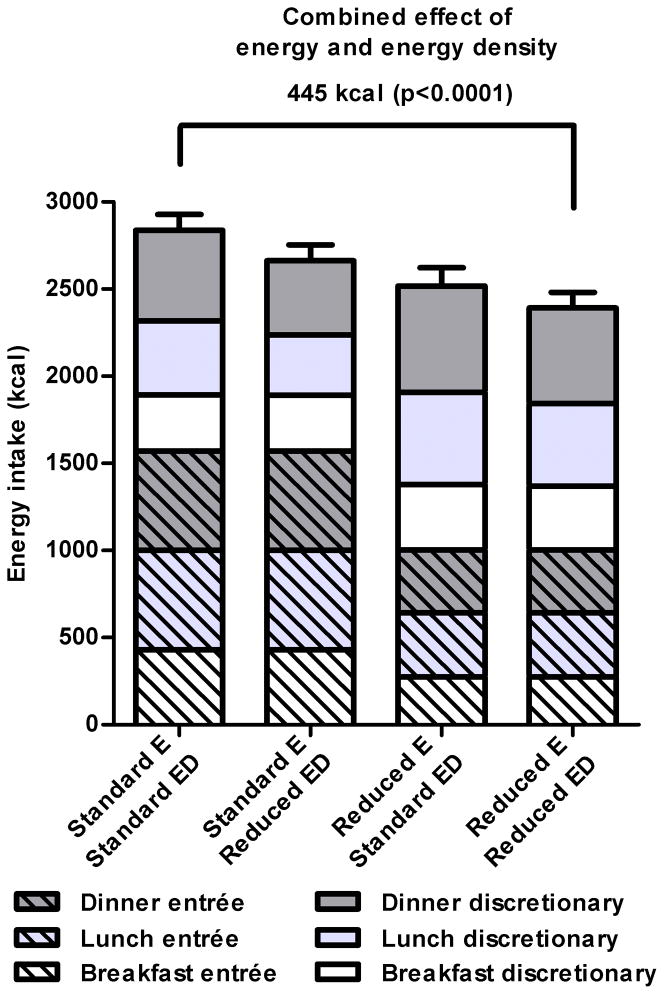

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) energy intake for 28 men who were served compulsory entrées that were varied in energy content (E) and energy density (ED), followed by a variety of discretionary foods. The effects of the experimental factors on daily energy intake were independent and significant (both P < 0.003). Reducing both the energy content and ED of the entrées resulted in a 445 kcal decrease in daily energy intake (P < 0.0001).

Table 5.

Total daily food and energy intakes of participants

| Standard energy content

|

Reduced energy content

|

P values

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard ED | Reduced ED | Standard ED | Reduced ED | Energy effect1 | ED effect2 | Interaction3 | |

| Men (n = 28) | |||||||

| Discretionary food intake (g) | 847 ± 65 | 687 ± 63 | 989 ± 77 | 893 ± 69 | <0.01 | <0.01 | -- |

| Discretionary energy intake (kcal) | 1267 ± 92 | 1094 ± 91 | 1515 ± 105 | 1389 ± 91 | <0.01 | <0.01 | -- |

| Discretionary ED (kcal/g) | 1.53 ± 0.08 | 1.66 ± 0.10 | 1.57 ± 0.07 | 1.65 ± 0.09 | NS | NS | -- |

| Daily food intake (g) | 1844 ± 65b | 2249 ± 63c | 1622 ± 77a | 1890 ± 69b | -- | -- | <0.001 |

| Daily energy intake (kcal) | 2837 ± 92 | 2664 ± 91 | 2518 ± 105 | 2392 ± 89 | <0.01 | <0.01 | -- |

| Daily ED (kcal/g) | 1.54 ± 0.03c | 1.18 ± 0.02a | 1.57 ± 0.04c | 1.27 ± 0.03b | -- | -- | <0.01 |

| Women (n = 40) | |||||||

| Discretionary food intake (g) | 604 ± 41b | 498 ± 41a | 721 ± 42c | 678 ± 44bc | -- | -- | <0.01 |

| Discretionary energy intake (kcal) | 969 ± 58b | 807 ± 57a | 1133 ± 60c | 1083 ± 54bc | -- | -- | <0.01 |

| Discretionary ED (kcal/g) | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 1.71 ± 0.09 | 1.61 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | NS | NS | -- |

| Daily food intake (g) | 1300 ± 41b | 1592 ± 41c | 1162 ± 42a | 1374 ± 44b | -- | -- | <0.001 |

| Daily energy intake (kcal) | 2069 ± 58c | 1907 ± 57b | 1830 ± 60ab | 1780 ± 54a | -- | -- | <0.01 |

| Daily ED (kcal/g) | 1.60 ± 0.03c | 1.19 ± 0.02a | 1.58 ± 0.04c | 1.29 ± 0.03b | -- | -- | <0.0001 |

All values are means ± SEMs. ED: energy density

Significance of effects of entrée energy content. All effects were independent of entrée ED.

Significance of effects of entrée ED. All effects were independent of entrée energy content.

Significance of the interaction of the effects of entrée energy content and entrée ED.

Means within the same row with different letters are significantly different

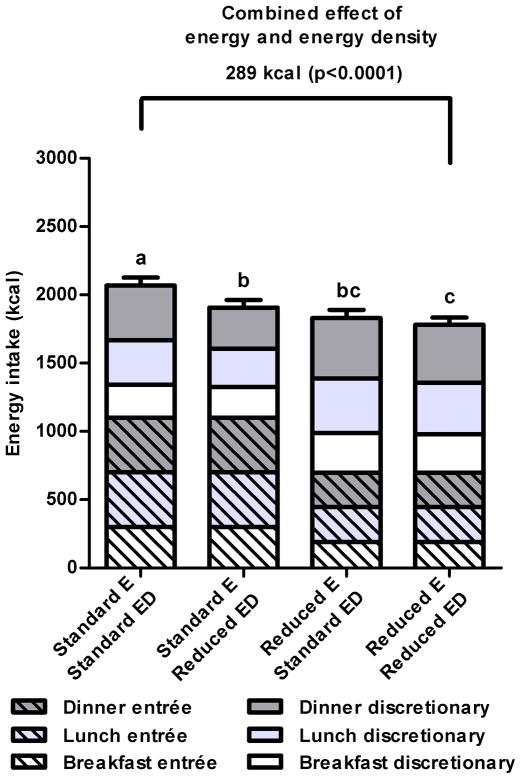

In women, reducing the energy content of entrées resulted in significant increases in discretionary energy intake and reductions in daily energy intake, but the magnitude of these changes depended on the level of entrée ED (P < 0.03; Figure 2). Decreasing the energy content of the standard-ED entrées reduced mean daily intake by 239 ± 30 kcal or 12%, and decreasing the energy content of the reduced-ED entrées reduced daily intake by 127 ± 39 kcal or 7% (Table 5). Analysis of each meal showed that in women, the effect of energy content on discretionary and total energy intake was independent of ED at breakfast and lunch (P < 0.001). At dinner, however, the effects of entrée energy content and ED interacted to affect discretionary and total energy intake (P < 0.003).

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) energy intake for 40 women who were served compulsory entrées that were varied in energy content (E) and energy density (ED), followed by a variety of discretionary foods. The experimental factors interacted to affect daily energy intake; different letters represent means that are significantly different (P < 0.03). Reducing both the energy content and ED of the entrées resulted in a 289 kcal decrease in daily energy intake (P < 0.0001).

The standard entrées provided a mean of 56 ± 1% of the estimated daily energy requirements for men and 50 ± 1% of the daily requirements for women; these proportions were similar to the intended range of 50 to 60% in the study design. When discretionary energy intake was included, men met 100 ± 3% of their daily energy requirements in the standard condition and women met 95 ± 3% of their requirements.

Effects of entrée energy density

In men, decreases in entrée ED resulted in a significant effect on daily energy intake, independent of decreases in entrée energy content (Figure 1). Reducing the ED of entrées led to a significant reduction in energy intake from discretionary foods (P < 0.005) and over the day (P < 0.01) of 150 ± 26 kcal, or 5% (Table 5). Analysis of each meal showed that in men, the effect of entrée ED on discretionary and total energy intake was significant at lunch and dinner (P < 0.03). In women, decreasing the ED of the entrées led to different effects depending on the energy content of the entrées (Figure 2). In the entrées with standard energy content, decreasing the ED had significant effects on discretionary and daily energy intake (P < 0.002); the reduction in daily intake was 162 kcal ± 34 or 8% (Table 5). In the entrées with reduced energy content, however, decreasing the ED had no significant effect on discretionary or daily energy intake (P = 0.59); the 50 ± 33 kcal difference in daily intake was not statistically significant.

Combined effects of entrée energy content and energy density

Comparing the entrées of equal portion size allowed evaluation of the combined effects of energy content and ED (Figures 1 and 2). In both men and women, this comparison showed that simultaneously decreasing entrée energy content and ED resulted in a significant reduction in daily energy intake. In men, the reduction in daily energy intake was 445 ± 47 kcal, or about 16% (P < 0.0001), and in women, the reduction was 289 ± 35 kcal, or about 14% (P < 0.0001).

Food intake

Daily food intake (weight) varied with the portion size of the compulsory entrées, which was determined by the combination of their energy content and ED (P < 0.001; Table 5); the pattern of effects was the same for men and women. Participants consumed the greatest daily amount of food when served the largest entrées (standard energy content, reduced ED), and the least amount of food when served the smallest entrées (reduced energy content, standard ED). Daily food intake was not significantly different when participants consumed the entrées of equal portion size. Similarly, the amount of time it took participants to consume the entrées was greatest when served the largest entrées, and least when served the smallest entrées (P < 0.0001; data not shown).

Energy density

The overall ED of the discretionary foods consumed at each test meal was not significantly affected by the variations in the compulsory entrées. Thus, dietary ED for the entire day was determined by the combination of entrée energy content and ED (P < 0.02; Table 5). Dietary ED was highest when participants consumed the entrées of standard ED, followed by the entrée of reduced energy content and reduced ED, and lowest when participants consumed the entrée of standard energy content and reduced ED.

Ratings of hunger, fullness, and food characteristics

The factors of entrée energy content and ED independently influenced ratings of hunger, as assessed by the summary measure of the area under the curve of ratings across the day. In both men and women, there was a significant effect of entrée energy content on daily hunger (P < 0.02), indicating increased hunger when the entrées were of reduced energy content (373 ± 11 in men; 374 ± 8 in women) rather than standard energy content (338 ± 10 in men; 349 ± 8 in women). In addition, in women there was an independent effect of entrée ED (P < 0.04), indicating decreased hunger when the entrées were reduced in ED and thus larger in portion size (349 ± 10) rather than of standard ED (373 ± 8).

The summary measure of fullness was dependent on the interaction between entrée energy content and ED. In both men and women, daily fullness was significantly greater when the entrées were of standard energy content and reduced ED (i.e., largest portion) than when the entrées were of reduced energy content at either ED (P < 0.04). In addition, in women daily fullness in this condition was also greater than in the standard condition (P < 0.01). Ratings of thirst and nausea did not differ significantly by the experimental factors at any time point or over the day for either men or women (data not shown). Ratings of pleasantness of appearance, taste, and texture of the manipulated entrées did not differ significantly across conditions for men or women (data not shown). Mean ratings of pleasantness of taste for the breakfast, lunch, and dinner entrées, respectively, were 68 ± 2, 65 ± 2, and 69 ± 2 in men and 78 ± 1, 72 ± 1, and 70 ± 1 in women. For ratings of calorie content of the entrées, there was a significant effect of entrée energy content in both men and women for the lunch entrée and only in women for the dinner entrée. Men and women rated the calorie content higher in the standard-energy lunch entrées (57 ± 2 in men; 59 ± 2 in women) than the reduced-energy versions (51 ± 2 in men; 55 ± 2 in women; P < 0.03). Women rated the standard-energy entrées at dinner higher in calories (61 ± 2) than the reduced-energy entrées (58 ± 2; P < 0.05).

Subject characteristics

Analysis of covariance demonstrated that the relation between the experimental factors of entrée energy content and ED and the outcome of daily energy intake was not significantly affected by participant age, height, weight, or body mass index. The outcomes were also not significantly affected by scores for dietary restraint, disinhibition, or hunger in women, nor by scores for dietary restraint and disinhibition in men. In men, the score for tendency toward hunger (20) significantly affected the relation between the experimental factors and the outcome of total energy intake over the day (P < 0.01). Daily energy intake increased with increasing score for tendency toward hunger only when the entrées smallest in portion size were consumed (P = 0.006).

Discharge questionnaire

Comments from the discharge questionnaire reported that 60 of 68 participants (88%) noticed that the manipulated entrées varied in the amount of food. Twenty-one participants (31%) noticed that the amount of vegetables in the entrées was different. When asked about the purpose of the study, 11 participants (16%) reported that the purpose was to determine how variations in the portion size or volume of entrées affected intake of other foods. No participants accurately discerned the purpose of the study was to determine the effect of varying the energy content and ED of entrées on energy intake.

DISCUSSION

Consumption of pre-portioned entrées has been shown to be a beneficial strategy for weight loss, but little is known about how the characteristics of entrées, including energy content and ED, influence satiety. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of these characteristics of pre-portioned entrées on satiety and daily energy intake when a variety of discretionary foods was available. It was found that in non-dieting men and women, reducing both the energy content and ED of compulsory entrées led to decreases in daily energy intake even when various other foods could be consumed ad libitum. In addition, ratings of hunger and fullness were affected by the energy content and the ED of the entrées. These findings extend previous work showing the importance of energy content and ED in determining satiety, as well as demonstrating the utility of pre-portioned entrées in moderating energy intake and reducing consumption of discretionary foods. The results of this study suggest that both the energy content and ED of pre-portioned entrées affect daily energy intake and could influence the effectiveness of such foods for weight management.

Although reducing the energy content of the entrées led to an increase in consumption of discretionary foods, the compensatory response was incomplete, resulting in a decrease in daily energy intake. Furthermore, the 36% reduction in entrée energy content had a greater effect on daily energy intake than did the similar reduction in ED. These findings suggest that reductions in energy content (achieved by decreasing portion size) may be more beneficial in controlling intake than decreases in ED (achieved by maintaining energy content and increasing portion size). However, if entrées provide so little energy that they leave the consumer hungry, their effectiveness in reducing daily energy intake may be compromised by greater consumption of discretionary foods (11–13). In the present study, the decreased energy intake that resulted from reducing entrée energy content was accompanied by a significant increase in ratings of hunger across the day. Outside the lab, such increased hunger could translate into greater intake of tempting, high-ED foods; this would limit the effectiveness of reductions in energy content that are achieved simply by reducing the amount of entrée served.

One approach that might help control intake of additional foods is to provide entrées that are reduced in ED and provide a satisfying portion. We found that reducing the ED of pre-portioned entrées, thus increasing their portion size, led to a decrease in consumption of discretionary foods as well as a reduction in energy intake over the day. These results confirm several preloading studies showing that reducing the ED of equicaloric preloads results in an increase in fullness ratings (14,15,28) and a decrease in both consumption of other foods and energy intake at a meal (14–17,28). Multiple experimental studies have also shown that when an entrée is consumed ad libitum, reducing the ED by increasing the proportion of fruits or vegetables decreases meal energy intake (29–32). In the present study, reducing the ED of the compulsory entrées led to the consumption of a greater weight of food over the day and higher ratings of fullness. Furthermore, fullness ratings were greatest after consumption of the entrées largest in portion size (those with standard energy and reduced ED), suggesting that portion size was important in influencing fullness. It is likely that the decrease in energy intake from consuming entrées reduced in ED was due to enhanced satiety from eating a greater amount of food; thus, individuals felt fuller while consuming less energy over the day.

Comparing entrées that were matched in weight allowed the combined effects of energy content and ED to be separated from those related to portion size. Simultaneously reducing both the energy content and ED of the pre-portioned entrées, while maintaining the portion size, resulted in a decrease in daily energy intake of 16% in men and 14% in women. Previous research has shown that when portion size is held constant, reductions in the energy content and ED of preloads enhance satiety and decrease subsequent energy intake. One study found that meal energy intake was decreased by consuming a salad preload that was reduced in energy and ED but matched in portion size (16). Another investigation showed that consuming a compulsory breakfast and mid-morning snack that were reduced in ED but provided the same amount of food led to reductions in daily energy intake (33). Similarly, participants in the current study did not fully compensate for the reduction in entrée energy content when portion size was matched, even when given the opportunity to consume a variety of discretionary foods. Thus, reductions in ED may be beneficial in maintaining portion size and enhancing satiety when pre-portioned entrées are decreased in energy content.

Men and women had some differences in their response to the manipulation of entrée characteristics. In men, there were independent effects of entrée energy and ED on energy intake at individual meals and over the day, whereas in women there were independent effects of entrée energy at breakfast and lunch but an interaction of energy and ED at dinner and over the day. These differences may be attributable to the smaller magnitude of the changes in energy content and portion size of the women’s entrées across the experimental conditions, since women received 70% of the amount of the compulsory entrées served to the men. Another reason for the difference may be the level of dietary restraint, which was significantly higher in women than men. An analysis of covariance, however, suggested that the restraint score did not have a significant influence on the relationship between the experimental conditions and daily energy intake. These findings suggest that further investigation is needed to determine how variations in the properties of foods may influence satiety and energy intake differently in men and women.

The results of this study indicate that modifying the characteristics of pre-portioned entrées led to decreased energy intake in non-dieting individuals even when a variety of other foods was available. Individuals who use pre-portioned entrées for the purpose of weight loss may respond differently to alterations in the characteristics of such foods. Dieters may experience even greater reductions in energy intake since they have an increased focus on limiting their intake of additional foods. To investigate this possibility, studies are needed in which individuals who are motivated to lose weight are provided with pre-portioned entrées that vary in energy content and ED. It also should be determined whether the findings from this one-day study would persist over a longer period. For long-term success at weight loss, it may be critical to consume foods that provide adequate energy and satisfying portions, thus avoiding feelings of hunger during caloric restriction. Previous research suggests that the effects of reductions in dietary ED on energy intake can be sustained over time. Two clinical trials found that following diets with larger reductions in ED resulted in greater weight loss after one year (34–35). Analyses from another trial of lifestyle modification to reduce hypertension showed that individuals with the greatest reductions in dietary ED had the largest decreases in body weight (36). Future studies are needed to investigate how modifying the characteristics of pre-portioned entrées affects long-term energy intake and weight management.

In conclusion, reductions in both the energy content and ED of pre-portioned entrées added together to decrease daily energy intake. Adding fruit and vegetables to decrease the ED of entrées allowed the portion size to be maintained while energy content was reduced, which contributed to enhanced satiety. The findings from this study suggest that in an environment that regularly exposes individuals to a variety of palatable high-ED foods, consuming pre-portioned entrées that are lower in ED can decrease discretionary energy intake. Since pre-portioned entrées are often used for weight management, more systematic exploration of the attributes of these foods is needed. It is crucial to provide consumers with a variety of options of pre-portioned entrées that are effective in enhancing satiety and moderating energy intake.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants DK59853 and DK39177.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(4):713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 May;27(5):537–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flechtner-Mors M, Ditschuneit HH, Johnson TD, Suchard MA, Adler G. Metabolic and weight loss effects of long-term dietary intervention in obese patients: four-year results. Obes Res. 2000;8:399–402. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheskin LJ, Mitchell AM, Jhaveri, et al. Efficacy of meal replacements versus a standard food-based diet for weight loss in type 2 diabetes: a controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(1):118–27. doi: 10.1177/0145721707312463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heymsfield SB. Meal replacements and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannum SM, Carson L, Evans EM, et al. Use of portion-controlled entrees enhances weight loss in women. Obes Res. 2004;12(3):538–546. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hannum SM, Carson LA, Evans EM, et al. Use of packaged entrees as part of a weight-loss diet in overweight men: an 8-week randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8(2):146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metz JA, Stern JS, Kris-Etherton P, et al. A randomized trial of improved weight loss with a prepared meal plan in overweight and obese patients: impact on cardiovascular risk reduction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2150–2158. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pi-Sunyer FX, Maggio CA, McCarron DA, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of a comprehensive prepared meal program in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(2):191–197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blundell J, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, et al. Appetite control: methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obes Rev. 2010;11(3):251–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Graaf C, Hulshof T. Effects of weight and energy content of preloads on subsequent appetite and food intake. Appetite. 1996;26:139–151. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray R, French S, Robinson T, Yeomans M. Dissociation of the effects of preload volume and energy content on subjective appetite and food intake. Physiol Behav. 2002;76(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RW, French SJ, Robinson TM, Yeomans MR. Increasing preload volume with water reduces rated appetite but not food intake in healthy men even with minimum delay between preload and test meal. Nutr Neurosci. 2003;6(1):29–37. doi: 10.1080/1028415021000056032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolls BJ, Castellanos VH, Halford JC, et al. Volume of food consumed affects satiety in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:1170–1177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Thorwart ML. Water incorporated into a food but not served with a food decreases energy intake in lean women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4):448–455. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Salad and satiety: energy density and portion size of a first course salad affect energy intake at lunch. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Chow M, Pelkman CL, Thorwart ML. Energy density but not fat content of foods affected energy intake in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:863–871. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zung WWK. Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory. In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, editors. Assessment of Depression. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garner DM, Olsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med. 1982;12:871–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS. [Accessed September 9, 2009.];What We Eat in America, NHANES 2007–2008. 2010 Aug; www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg.

- 24.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 21, 2008. [Accessed September 1, 2009.];Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl.

- 25.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(1):38–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Kettel-Khan L, et al. Dietary energy density determined by eight calculation methods in a nationally representative United States population. J Nutr. 2005;135:273–278. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(7):916–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poortvliet PC, Berube-Parent S, Drapeau V, Lamarche B, Blundell JE, Tremblay A. Effects of a healthy meal course on spontaneous energy intake, satiety and palatability. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(3):584–590. doi: 10.1017/S000711450738135X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Pelkman CL, Thorwart ML, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake in normal-weight women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:412–420. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size on energy intake in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:962–968. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:11–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blatt AD, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Hidden vegetables: an effective strategy to reduce energy intake and increase vegetable intake in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.009332(2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazlan N, Horgan G, Stubbs RJ. Energy density and weight of food effect short-term caloric compensation in men. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(4):679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Beach AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Provision of foods differing in energy density affects long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 2005;13:1052–1060. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ello Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1465–1477. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, et al. Reductions in dietary energy density are associated with weight loss in overweight and obese participants in the PREMIER trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1212–1221. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]