Abstract

Visible indication based on the aggregation of colloidal nanoparticles (NPs) is highly advantageous for rapid on-site detection of biological entities, which even untrained persons can perform without specialized instrumentation. However, since the extent of aggregation should exceed a certain minimum threshold to produce visible change, further applications of this conventional method have been hampered by insufficient sensitivity or certain limiting characteristics of the target. Here we report a signal amplification strategy to enhance visible detection by introducing switchable linkers (SLs), which are designed to lose their function to bridge NPs in the presence of target and control the extent of aggregation. By precisely designing the system, considering the quantitative relationship between the functionalized NPs and SLs, highly sensitive and quantitative visible detection is possible. We confirmed the ultrahigh sensitivity of this method by detecting the presence of 20 fM of streptavidin and fewer than 100 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli.

Visible indication based on the aggregation of colloidal nanoparticles (NPs) is highly advantageous for rapid on-site detection of biological entities, which even untrained persons can perform without specialized instrumentation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, since the extent of aggregation should exceed a certain minimum threshold to produce a visible change, further applications of this method have been hampered by insufficient sensitivity10 or certain limiting characteristics of the target11. Here we report a simple and facile biosensing strategy controlling the extent of NPs aggregation, which provides several strategic options to design and to enhance the visible detection of wide-ranging targets. Between the two well-known mechanisms for aggregating NPs12, interparticle crosslinking mechanism allows controlling the extent of aggregation via a quantitative relationship between the functionalized NPs (f-NPs) and the linkers13,14. Advances in nanotechnology help to ensure the reproducibility in controlling the extent of aggregation14. Further, the crosslinking mechanism is more specific12,15 and less influenced by the sample conditions than the non-crosslinking mechanism2,8,16,17, which obviates sophisticated sample preparation steps.

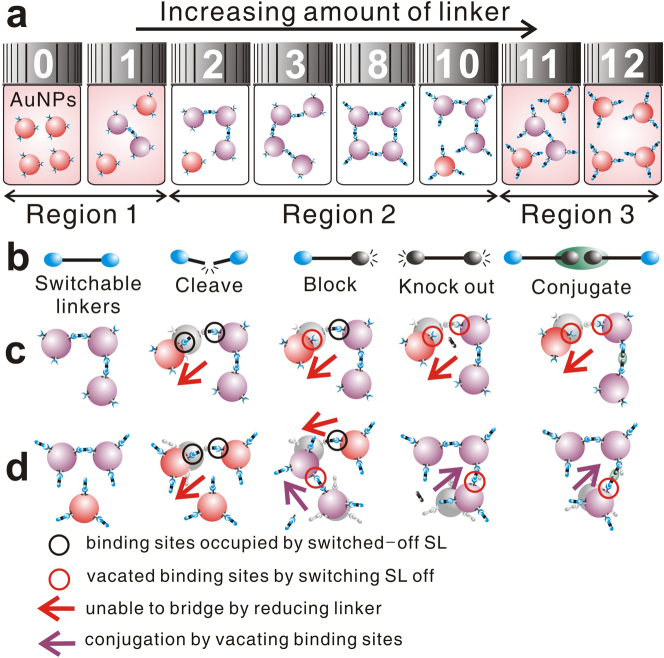

The extent to which f-NPs aggregate via crosslinking is determined by the number of linkers, available binding sites, and NPs in the system (see supplementary information). For a given number of f-NPs with multiple binding sites, there is a range of linker concentration, which can induce their aggregation to an extent over a minimum threshold sufficient to exhibit a visible color change (Fig. 1a, Region 2). Otherwise, color change is imperceptible due to either the lack of sufficient linkers to cause aggregation (Region 1) or the presence of excess linkers (Region 3), which prevents the bridging of the NPs. When the number of effective linkers (nLK) available to bridge the f-NPs is altered, the range of linker concentration exhibiting visual color change (REVC) takes different set of values from that for the control system. Thus, once the control REVC is well established, even a slight change in nLK can produce visually distinguishable difference, especially at the boundaries of the control REVC, and the extent of difference in REVC quantitatively indicates the change in nLK. Accordingly, the mechanism for producing an indication signal is independent from that for target recognition, which affords the opportunity to amplify the signal and allows designing quantitative colorimetric detection systems for wide-ranging targets.

Figure 1.

(a) Linker concentration can be grouped into three regions for a given amount of NPs based on the observable visual color change. Numbers on the bottle lids represent the number of linkers. (b) Different possible SL designs (top row) and the corresponding effects of switching off SLs to reduce the nLK by 1 at low (middle row) and high (bottom row) concentration of SL.

To attain detection based on the proposed scheme, we introduce the concept of switchable linkers (SLs) to alter the nLK based on the presence of target. The SL is an element allowing multiple specific bindings, which can be selectively enabled or disabled to bridge f-NPs. When some SLs are disabled (switched off) to function as a linker, the nLK decreases changing the chance for the f-NPs to aggregate to an expected extent. The consequence of switching off SLs is that some binding sites on NPs, which could have been occupied by those SLs, become “vacant”. Because the switched-off SLs remain in the system and can compete for the binding sites, the vacating effect varies according to the SL design (Fig. 1b).

When nLK is less than a certain minimum, the reduced nLK by switching SL off should lower the extent of aggregation regardless of the SL design. Because the binding sites compete for linkers to bridge f-NPs, the nLK determines the extent of aggregation and the vacating effect is negligible. Therefore, at the low end of REVC, where the fewest number of SLs is present to induce visible change in the control system, the effect of switching off an SL is to reduce nLK by 1 lowering the possibility to bridge the f-NPs. However, when nLK exceeds a certain maximum, the linkers compete to occupy the binding sites for conjugating f-NPs. Thus, the number of binding sites available to bridge NPs determines the extent of aggregation, and the vacating effect of switching SL off rather than the change in nLK dictates the change in the extent of aggregation. Subsequently, at the high end of REVC, where the number of SLs present is just over the maximum to induce visible change, the effect of switching SL off on the extent of aggregation varies according to the SL design.

Result

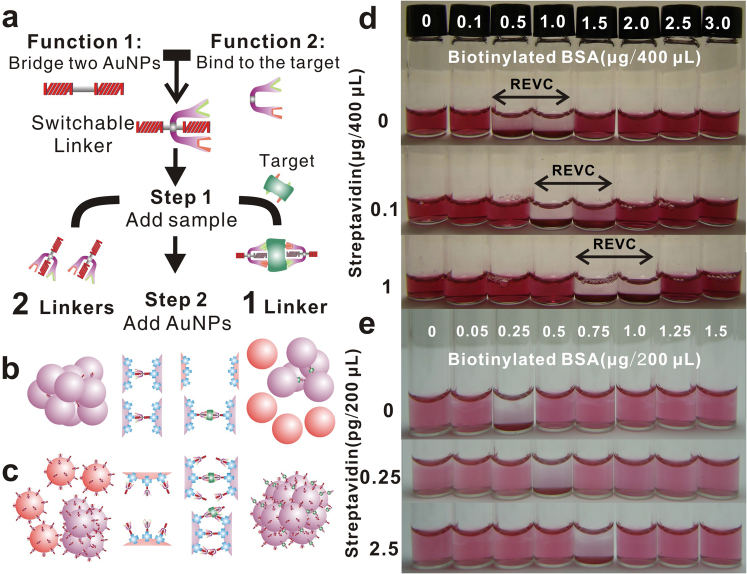

We demonstrated the effectiveness of SLs-based assay by designing a system for sensing a model target streptavidin, which is a protein with multiple binding sites. The applicability of the assay in achieving exceptional sensitivity was also evaluated in colorimetric detection of the bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli). A molecule that can selectively bind the target can play the role of SL, when it is functionalized to bridge two f-NPs. This SL design is effective for detecting the target with multiple binding sites by performing two functions: 1. bridging two f-NPs and 2. binding to the target selectively forming a complex with other SLs, which decreases nLK (Fig. 2a). The formation of such linker complex fulfills the condition for switching SLs off, if the number of f-NPs that a complex can bridge is less than that those SLs should bridge individually. If so, the presence of targets in the sample can effectively cause the change in the extent of aggregation, when the assay is performed in two steps. First, mixing SLs with the sample and then adding f-NPs for SLs to mediate the aggregation of NPs. By promptly introducing the sample to the SLs (Step 1), targets crosslink with SLs to form a linker complex, which reduces nLK (from 2 to 1, as shown here for illustration) for crosslinking with the f-NPs (Step 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Scheme of the two-step assay using an SL designed in “conjugate” fashion for detecting a target with multiple binding sites. (b) Effect of switching SLs off on decreasing the extent of aggregation of NPs, when nLK determines the aggregation. (c) Effect of switching SLs off on increasing the extent of aggregation of NPs, when the number of unoccupied binding sites determines the aggregation. (d) Color of the test system with different amounts of bBSA at 2 h after performing the assay for detecting streptavidin using a known concentration of stAuNPs (absorption: 0.43 @ 531 nm for 1/10 diluted sample) (e) Test system scaled-down (one-half of d) with one-half concentration of stAuNPs (absorption: 0.21 @ 531 nm for 1/10 diluted sample), which enhances the detection sensitivity down to 2×10-14 M.

Detection of streptavidin was achieved by employing biotinylated bovine serum albumin (bBSA) molecule labeled with 8–16 biotin molecules, as the SL for aggregating gold NPs (average diameter ~13 nm) functionalized with multiple streptavidin molecules (stAuNPs). Thus, as required, bBSA can both specifically conjugate the target streptavidin and bridge two stAuNPs. And a streptavidin molecule can conjugate with at least two bBSA molecules, because streptavidin is a tetramer. Consequently, the target streptavidin molecules in the sample will crosslink with some bBSAs to form a complex (Fig. 2a). Since the size of the bBSA is vastly different from that of the stAuNPs, the condition for switching off SLs is readily achieved. Though target mediated linker complex still can bridge stAuNPs, one unit of linker complex cannot bind a third stAuNP unless it grew very large, which requires large amounts of bBSA and streptavidin. Therefore, the presence of target streptavidin disables some bBSA molecules both from conjugating stAuNPs at the low end of REVC (Fig. 2b) or occupying the binding sites on stAuNPs at the high end of REVC (Fig. 2c).

Consequently, REVC shifts to a higher concentration of bBSA in proportion to the reduction in nLK. Thus, as we increased the content of target streptavidin in the sample, the REVC spanned over higher bBSA concentrations (Fig. 2d) because of increased extent of conjugation between the target streptavidin and bBSA, which is also a function of time (see supplementary information). In the target-free control system, REVC was from 0.5 to 1.0 μg of bBSA for ~3×1012 particles of stAuNPs in 400 mL (see supplementary information). When the target streptavidin was present, decreased extent of aggregation at the low end of REVC (containing 0.5 μg of bBSA) caused the system color to remain red. While, increased extent of aggregation at the high end of REVC (containing 1.5 μg of bBSA) produced visually distinguishable color change. As the result, REVCs of each test performed with samples containing 0.1 and 1.0 μg of target streptavidin were from 1.0 to 1.5 and from 1.5 to 2.0 μg of bBSA, respectively. Further, because the quantitative relationship between the target, SLs and f-NPs, determines the shift in REVC to higher SL concentration against a certain amount of target (see supplementary information), the system with smaller amount of f-NPs should allow more sensitive detection. Indeed, the test system with amount of stAuNPs reduced by 1/4 produced a visible signal when detecting even ~1.25 pg/mL (20 fM) of streptavidin (Fig. 2e).

The SL design just described to compose the linker complex is highly effective to facilitate the change in the extent of aggregation in the presence of target, when the size of target is much smaller than that of NPs. While, for targets that are as large as the bacteria, the key feature for designing SL should be that a target has thousands of receptor molecules. In fact, immunogenic attachment of NPs on the cell surface using functionalized antibody (f-Ab) has been reported to produce an optical signal for selective detection of bacteria16,18,19,20,21. However, if only those f-NPs attached on the cell surface produce the optical signal, it would be too faint to be visible, especially at low cell loads (see supplementary information).

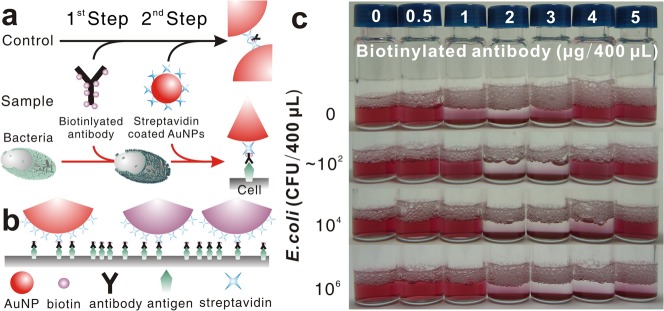

Our strategy to control the extent of aggregation via the SLs provides exceptional sensitivity to NPs-based visible detection of bacteria using immunoreaction. If f-Abs can bridge two f-NPs, they can play the role of SLs. Since the size of f-Abs is too small relative to those of the bacteria and f-NPs, the ability of an f-Ab to bridge two f-NPs is switched off, when an f-Ab binds to an antigen on the cell surface (Fig. 3a). Thus, the presence of bacteria should reduce nLK by promptly binding some f-Abs to possible antigens on the cell surface. Moreover, since the f-NPs are much larger than the inter-antigen spacing, the f-NPs that attach to the cell may occlude some f-Abs bound to antigens making those f-Abs unavailable to occupy any binding sites on the f-NPs (Fig. 3b). When biotinylated anti-E.coli polyclonal antibody (b-Ab), labeled with 7–10 biotin molecules, was used as SL to facilitate the aggregation of stAuNPs, the presence of E. coli in PBS shifted the REVC to higher concentrations, as expected, providing exceptional sensitivity (Fig. 3c). However, the REVC became wider with the increasing cell load, experiencing a larger shift at the high end than at the low end.

Figure 3.

Scheme of (a) the two-step assay for visible detection of bacteria using biotinylated antibody (b-Ab) as SLs to control the extent of aggregation of stAuNPs. (b) Relative difference between the size of the cell and that of NPs on switching b-Abs off when they attach on the cell surface. (c) Shift of REVC in response to the presence of E. coli, when tests performed using biotinylated antibody (b-Ab) as SL in 400 μL total sample volume with a fixed stAuNPs concentration (absorption: 0.43 @ 531 nm for 1/10 diluted sample) and. E.coli cell loads are typical of several tests, which yielded similar results.

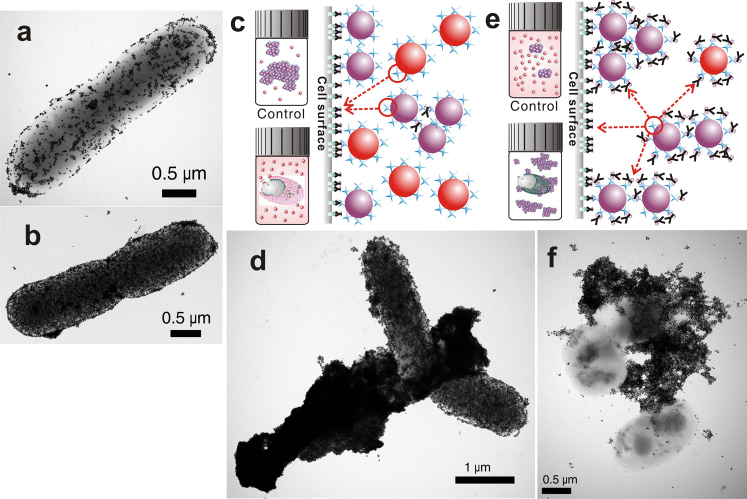

By binding the surface antigens of bacteria, switched-off f-Abs can mediate the attachment of f-NPs on the cell surface, which also gathers f-NPs as if they were aggregating. However, immunogenic attachment cannot gather f-NPs as densely as interparticle aggregation, because it is unlikely that the f-NPs attach to the cell uniformly and in close proximity, especially when NPs are small and spherical (Fig. 4a)16,22. Moreover, even the monolayer attachment (Fig. 4b), the best possible means of gathering f-NPs via immunogenic attachment, cannot induce the surface plasmon resonance coupling effect as intensely as three-dimensional aggregation could23,24. Therefore, the effect of switching SLs off by the presence of bacteria on the change in the extent of aggregation is to both facilitate the attachment of f-NPs on cell surface and reduce the number of f-Abs available for interparticle conjugation.

Figure 4.

TEM image of (a) sparsely attached stAuNPs on an E. coli cell due to lack of sufficient b-Abs, which would also occur when the antigens are not uniformly distributed, and (b) monolayer immunogenic attachment of stAuNPs on an E. coli cell surface. (c) Effect of switching f-Abs off when the bacteria are present in the system on the extent of aggregation at the low end REVC. Red arrow indicates possible conjugation. d) TEM image of stAuNPs aggregation in the presence of E.coli (107 CFU) at 2 μg/400 μL of b-Ab, where the immunogenic attachment is favoured. (e) The role of bacteria switching b-Abs off to increase the extent of aggregation at the high end REVC. (f) TEM image of stAuNPs aggregation in the presence of E.coli (107 CFU) at 5 μg/400 μL of b-Ab, where the aggregation of stAuNPs is favoured.

When the extent of aggregation is determined by the nLK, especially at the low end of REVC, antecedently conjugated f-Abs on cell surface leads some f-NPs, which should have been aggregated in the absence of bacteria, to attach on the cell surface (Fig. 4c). Accordingly, f-NPs are more prone to cover the bacteria, even though some unbound f-Abs are left to induce the aggregation of f-NPs (Fig. 4d). Therefore, the effect of immunogenic attachment is significant on the change in the extent of aggregation, but may vitiate the effect of switching b-Abs off to decrease the extent of aggregation.

On the other hand, the presence of bacteria effectively increases the extent of aggregation at the high end of REVC, because the vacating effect of switching f-Abs off dictates the change in the extent of aggregation. When excessive amount of f-Abs prevents interparticle conjugation, as it happens at the high end of REVC, the bacteria take some f-Abs to vacate some binding sites on the f-NPs, which become available to bind f-Abs either attached to the cell surface or to other f-NPs (Fig. 4e). However, since the amount of f-Abs attached to the f-NPs far exceeds those attached on the cell surface, there is a greater probability for the f-NPs to conjugate with other f-NPs than to attach on the cell surface. Thus, even though all antigens on the cell surface should be conjugated with f-Abs promptly, the effect of switching off f-Abs encourages aggregation of f-NPs to a large extent in preference to immunogenic attachment of the f-NPs on the cell surface (Fig. 4f).

Discussion

The extraordinary sensitivity for visible detection of bacteria cell we achieved is attributed to accessing all antigens on the cell surface to produce the indication signal, rather than only those antigens that mediate the attachment of f-NPs. By the use of f-Abs as SLs, even a few target cells can alter the chance of conjugating NPs, which eventually changes the extent of SL-mediated aggregation of NPs. Since visible signal produced corresponds to the change in the function of SL, rather than the amount of target present in the sample, the concept of SL allows designing sensitive detection systems to overcome any limiting target characteristics. Moreover, the use of SLs affords an opportunity to amplify the signal, because the mechanism for producing indication signal is independent from that for target recognition, as is the basis of signal amplification strategies25,26.

Since the change in REVC is the indication signal, colorimetric detection can be useful both for detecting the presence of target based on a pre-set threshold in single batch test and for quantifying the target present by performing a series of tests. However, the response characteristics of SL-based detection system, which we did not discuss in this manuscript, can be varied according to the mechanism to switch SLs off and the quantitative relationship between the target and the switched off SLs. And the reproducibility in controlling the extent of NPs aggregation should be attributed to the uniformity in the number and the distribution of binding sites on each NP14. Further, our system can be tailored to detect different targets at any desired level by carefully optimizing the assay and by creatively designing the SL. Thus, if the advances in nano/biotechnologies employing other specific interactions (e.g., transcyclooctene–tetrazine27, oligonucleotides17 and so on) can help design novel SLs and strategies, adapting our concept can further enhance visible biosensing of targets that are difficult using conventional methods.

Methods

Preparation of streptavidin-coated gold nanoparticles

Spherical gold nanoparticles (AuNPs, average diameter = 13 nm) showing a peak UV-Vis spectra at 520 (± 0.5) nm of wavelength were prepared by reducing 1 mM tetrachloroaurate (Sigma Aldrich) by 1% (w/v) tri-sodium citrate. The AuNPs were functionalized with excessive streptavidin (Sigma Aldrich) to cover entire AuNPs and repeatedly washed to remove unbound streptavidin (see supplementary information). Streptavidin-coated AuNPs (stAuNPs), which exhibit an absorption peak at 531 (± 0.5) nm measured with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, were stored in 0.5% (w/v) of bovine serum albumin (BSA) dissolved phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at three concentrations giving peak absorbance values of 0.21, 0.43 and 0.86 (± 0.05) on the UV-Vis spectra for 1/10 dilution samples.

Specific agglomeration of AuNPs upon biotin-streptavidin interaction

The function of interaction between biotin-streptavidin to agglomerate AuNPs was examined by mixing multi biotin molecules are labeled substances (i.e., biotinlyated BSA (bBSA, Sigma Aldrich) or biotinylated anti-E.coli polyclonal antibody (b-Ab, GTX40640, Genetex) and streptavidin-coated AuNPs (stAuNPs). The specificity of observed agglomeration was verified by blocking the binding sites on stAuNPs with unbound biotin previously. 100 μL of biotin at 10 μg/mL was added to 200 μL of stAuNPs, by which the addition of b-Ab (10 μg/mL) did not produce visible color change at any concentration.

Two-step detection assay

The assay was designed using 400 μL overall volume: 200 μL of stAuNPs solution at fixed concentration, 100 μL of switchable linker (SL) and 100 μL of test sample. For the first step, 100 μL of the sample was mixed with 100 μL of SL promptly. After the elapse of reaction time (typically one hour for entire experiment) without stirring, 200 μL of prepared stAuNPs was added to the mixture and stirred vigorously. The reactions of mixed sample were allowed to progress without shaking and the color change was monitored as a function of elapsed time (supplementary information). The above tests were performed after scaling down the system by one-half to 200 μL overall volume. Note: actual weights instead of concentrations of reagents are used throughout, because it is possible to prepare stAuNPs and SLs in dehydrated form allowing the volume of sample up to overall test volume (see supplementary information).

Preparation of bacteria samples and verification of detected concentration of bacteria

The relationship between UV-Vis absorption spectra at 660 nm of wavelength and increasing population of bacteria, cultured in LB broth, was monitored and verified by conventional plate culture method using PetrifilmTM selective count plate (3M). A sample with 1×1011 CFU/mL of bacteria at exponential phase was picked and diluted in PBS to fit expected concentration of bacteria. The concentrations of bacteria sample both before and after performing the detection were also verified by plate culture.

Verification of the attachment and the effect on color of colloidal system

Bacteria samples pre-treated with b-Abs for attachment of AuNPs on cell surface were prepared as follows: 1010 CFU of bacteria in 1 mL of PBS was promptly reacted with 2 μg and 1 mg of b-Ab for sparse and monolayer attachment, respectively. After 2 h of incubation followed by several washing process with PBS to remove excessive b-Ab, b-Ab conjugated bacteria sample restored in 200 μL of PBS was mixed with 200 μL of stAuNPs in biotin dissolved PBS (0.5 % w/v) for specific attachment of AuNPs.

Transmission electron microscopy

To take transmission electron microscopic pictures (TEM, JEM1010, JEOL, Japan) at 80 kV, tests with E.coli at 107 CFU/mL were performed. Tested systems were centrifuged and washed with PBS to remove unbound stAuNPs. Washed samples were restored in 20 mM HEPES buffer to remove salt in PBS and sampled on grid for taking TEM pictures.

Author Contributions

S.L. originated the proposed strategy while working with S.G. (at UW-Madison). S.L. performed all the experiments with the help of Y.S.Y. Both Y.J.C (at SNU) and S.G. (at UW-Madison) supervised and managed the project. O.K.K. suggested verifying the attachment of AuNPs on the cell surface. J.H.Y. (at UW-Madison) and Y.E.L. (at SNU) prepared bacteria samples and performed verification, and D.H.K. advised on how to handle them. M.S.K. helped to verify the specificity of bindings. S.L. drafted the manuscript and D.H.K. P.S.C., Y.J.C. and S.G. revised and edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Enhancing Nanoparticle-Based Visible Detection by Controlling the Extent of Aggregation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2007-357-F00037). S.L. thanks S. Lee for his comments and suggestions.

References

- Leuvering J. H. W., Thal P. J. H. M., van der Waart M. & Schuurs A. H. W. M. Sol Particle Immunoassay (SPIA). J. Immunoassay 1, 77-91 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghanian R., Storhoff J. J., Mucic R. C., Letsinger R. L. & Mirkin C. A. Selective colorimetric detection of polynucleotides based on the distance-dependent optical properties of gold nanoparticles. Science 277, 1078-1081 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. W. & Lu Y. A colorimetric lead biosensor using DNAzyme-directed assembly of gold nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6642-6643 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storhoff J. J., Lucas A. D., Garimella V., Bao Y. P. & Muller U. R. Homogeneous detection of unamplified genomic DNA sequences based on colorimetric scatter of gold nanoparticle probes. Nat. Biotech. 22, 883-887 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chah S., Hammond M. R. & Zare R. N. Gold nanoparticles as a colorimetric sensor for protein conformational changes. Chem. Biol. 12, 323-328 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosi N. L. & Mirkin C. A. Nanostructures in Biodiagnostics. Chem. Rev. 105, 1547-1562 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarise C., Pasquato L., De Filippis V. & Scrimin P. Gold nanoparticles-based protease assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 3978-3982 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Chiuman W., Brook M. A. & Li Y. Simple and Rapid Colorimetric Biosensors Based on DNA Aptamer and Noncrosslinking Gold Nanoparticle Aggregation. Chem Bio Chem 8, 727-731 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liu Y., Mernaugh R. L. & Zeng X. Single chain fragment variable recombinant antibody functionalized gold nanoparticles for a highly sensitive colorimetric immunoassay. Biosens. Bioelectron. 24, 2853-2857 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Hosokawa K. & Maeda M. Rapid aggregation of gold nanoparticles induced by non-cross-linking DNA hybridization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 8102-8103 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J. M., Thaxton C. S. & Mirkin C. A. Nanoparticle-based bio-bar codes for the ultrasensitive detection of proteins. Science 301, 1884-1886 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Brook M. A. & Li Y. F. Design of Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Biosensing Assays. Chem Bio Chem 9, 2363-2371 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan K., Luhrs C. C. & Pérez-Luna V. H. Controlled and Reversible Aggregation of Biotinylated Gold Nanoparticles with Streptavidin. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 15631-15639 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Aili D. et al. Polypeptide Folding-Mediated Tuning of the Optical and Structural Properties of Gold Nanoparticle Assemblies. Nano Letters 11, 5564-5573 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. X. & Rothberg L. Colorimetric detection of DNA sequences based on electrostatic interactions with unmodified gold nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 14036-14039 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-C. et al. Selective Binding of Mannose-Encapsulated Gold Nanoparticles to Type 1 Pili in Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 3508-3509 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. & Lu Y. Fast Colorimetric Sensing of Adenosine and Cocaine Based on a General Sensor Design Involving Aptamers and Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 90-94 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. et al. A Rapid Bioassay for Single Bacterial Cell Quantitation Using Bioconjugated Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 15027-15032 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalele S. A. et al. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli by using anti body-conjugated silver nanoshells. Small 2, 335-338 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chungang W. & Joseph I. Gold Nanorod Probes for the Detection of Multiple Pathogens. Small 4, 2204-2208 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K. et al. Gold Nanorod Based Selective Identification of Escherichia coli Bacteria Using Two-Photon Rayleigh Scattering Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 3, 1906-1912 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda O. R. et al. Colorimetric Bacteria Sensing Using a Supramolecular Enzyme–Nanoparticle Biosensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9650-9653 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabar K. C., Freeman R. G., Hommer M. B. & Natan M. J. Preparation and Characterization of Au Colloid Monolayers. Anal. Chem. 67, 735-743 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Nath N. & Chilkoti A. A Colorimetric Gold Nanoparticle Sensor To Interrogate Biomolecular Interactions in Real Time on a Surface. Anal. Chem. 74, 504-509 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giljohann D. A. & Mirkin C. A. Drivers of biodiagnostic development. Nature 462, 461-464 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Ye Y. & Liu S. Gold nanoparticle-based signal amplification for biosensing. Anal. Biochem. 417, 1-16 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun J. B., Devaraj N. K., Hilderbrand S. A., Lee H. & Weissleder R. Bioorthogonal chemistry amplifies nanoparticle binding and enhances the sensitivity of cell detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 660-665 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Enhancing Nanoparticle-Based Visible Detection by Controlling the Extent of Aggregation