Abstract

Purpose

A 3-dose human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is recommended for adolescents to protect against HPV-related cervical and other cancers. The purpose of this study was to provide an update on HPV vaccine uptake among 11-17 year old girls residing in the US.

Methods

Data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were obtained to assess HPV vaccination status and its correlates. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine HPV vaccine uptake of ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses among all girls, and completion of the 3-dose series among those who initiated (received ≥1 dose) the vaccine.

Results

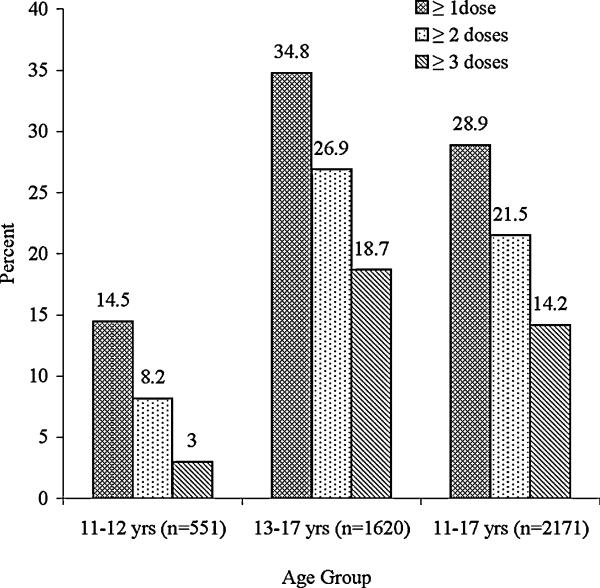

Overall, 28.9% and 14.2% received ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses of vaccine: 14.5% and 3.0% among 11-12 year old girls, and 34.8% and 18.7% among 13-17 year olds, respectively. Hispanics had higher uptake of ≥1 dose (odds ratio (OR) 1.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22-2.17) than whites. Having received an influenza shot in the past year and parents’ awareness of the vaccine were significantly associated with receiving ≥1 dose (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.51 -2.33 and OR 16.57, 95% CI 10.95 -25.06) and ≥3 doses (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.13 -1.92 and OR 10.60, 95% CI 5.95 -18.88). A separate multivariate model based on girls who initiated the vaccine did not identify any significant correlates of 3-dose series completion. Among parents of unvaccinated girls, 60% were not interested in vaccinating their daughters and mentioned three main reasons: “does not need vaccine” (25.5%), “worried about safety” (19.3%) and “does not know enough about vaccine” (16.6%). Of those who were interested, 53.7% would pay $360-$500 for the vaccination, while 41.7% preferred to receive it at a much lower cost or free.

Conclusions

Only 1 out of 3 girls (11-17 years) have received ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine and much less have completed all 3 doses. Strategies should be taken to improve this vaccine uptake among girls, especially those 11-12 year olds, and to educate parents about the importance of vaccination.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, HPV vaccine, Vaccine uptake, Vaccination, Adolescent, National Health Interview Survey

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 & 18 is responsible for 70% of cervical cancer, while most cases of genital warts are due to HPV 6 & 11 [1, 2]. Furthermore, persistent HPV infection has been identified as the primary cause of anogenital cancer [3]. In 2006, The United States Food and Drug administration (FDA) approved a quadrivalent HPV vaccine against types 6, 11, 16, and 18 [4] as a primary preventive strategy to reduce HPV infections and HPV-related cervical cancers. A bivalent HPV vaccine was also licensed in 2009, which provides protection against HPV types 16 and 18 [5]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended routine vaccination of either quadrivalent or bivalent HPV vaccine in girls aged 11 to 12 years and “catch-up” vaccination for girls and women aged 13 to 26 years in a 3-dose series which is administered over 6 months [4, 5]. These vaccines are highly effective in preventing HPV infections among HPV-naïve adolescent girls [4-7]. In 2011, ACIP extended their recommendations to include routine use of quadrivalent HPV vaccine for 11-12 year old males and “catch-up” vaccination for those 13 -21 years old [8].

Studies based on small sample sizes [9-17] and national surveys [18-22] have reported HPV vaccine uptake among US adolescent girls based on data collected after the vaccine was first introduced. All studies have shown low HPV vaccine uptake with notable differences in a variety of settings. Based on 2008 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)-child sample data, Wong et al [21] observed low uptake of ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses of HPV vaccine among 11-17 year old girls (23% and 9%, respectively) while 41% of those who initiated the vaccine completed the 3-dose series. In this study, we aimed to update estimates of HPV vaccine uptake of ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses among 11-17 year old girls, and completion of the 3-dose series among those who initiated the vaccine using 2010 NHIS-child sample data and to compare it with 2008 NHIS data [21]. In addition, we aimed to examine the correlates of uptake of ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses among all girls as well as the 3-dose series completion among those who initiated the vaccine.

Methods

Study population

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a cross-sectional, annual, in-person household survey conducted throughout the year [from January to December] by the National Center for Health Statistics/Center for Disease Control and Prevention (NCHS/CDC). This survey includes a nationally representative sample of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population selected through a complex, stratified, multistage probability sampling design. Hispanics, blacks and Asians were oversampled to ensure adequate representation and stable estimates for these racial and ethnic groups. Detailed methods of this survey have been published elsewhere [23]. The in-person interviews yielded demographic, socioeconomic and health status data for all members of each participating family. From each family, a child <18 years of age (the “sample child”) and an adult (the “sample adult”) were randomly selected for additional questions. In the 2010 NHIS-Sample Child Module, a total of 11,277 children <18 years of age were surveyed with an overall response rate of 70.7%. A parent (91% cases) or parent proxy (9% cases) answered questions on behalf of the “sample child”.

In the 2010 NHIS-Sample Child Module, the HPV vaccine related questions were administered to all families with adolescents who were age-eligible for HPV vaccination at the time of the survey [21]. We obtained data of girls aged 11-17 years (n=2205) from this module. Although this study used de-identified publicly available data, we required approval from the University of Texas Medical Branch institutional review board.

Data collection

This study focused on survey questions pertaining to HPV vaccination of adolescent girls aged 11-17 years. Parents’ awareness about HPV vaccine was assessed from the question, “Two vaccines/shots to prevent HPV infection are available in the US. Both vaccines prevent cervical cancer and one also prevents genital warts. The two HPV vaccines are sometimes called CERVARIX or GARDASIL. Before this survey, have you ever heard of HPV vaccines or shots?” The responses were “yes” or “no”. The receipt of the vaccine and number of vaccine doses were assessed from the parental responses to following two questions, “Did your child ever receive an HPV shot?” and “How many HPV shots did your child receive?” We measured receipt of ≥ 1 dose and ≥ 3 doses of vaccine from the number of shots received. Parents reported receipt of unknown number of vaccine doses for 28 girls and more than 3 doses for 10 girls (4 doses for 9, and 6 doses for 1) were included in the ≥ 1 dose and ≥ 3 doses categories, respectively. The denominator for receipt of ≥ 1 dose and ≥ 3 doses analyses included all girls, while the denominator for 3-dose vaccine series completion analysis included only those who had initiated the vaccine.

Whether parents of the unvaccinated girls would be interested in future vaccination of their daughters was assessed from the question, “If your child’s doctor recommended the HPV vaccine, would you have her get it?” The responses were “yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”. Among parents who responded “no” or “don’t know”, the main reason for not vaccinating their daughters were evaluated. The responses for the main reason included “does not need vaccine”, “worried about vaccine safety”, “do not know enough about vaccine”, “not sexually active”, “too young for vaccine”, “doctor did not recommend it”, “too expensive”, “don’t know about the place to get vaccine”, “spouse/family member against it”, “already has HPV”, “others”, and “donot know”. All the responses were mutually exclusive. Among parents who responded “yes” to the above question (who were interested in vaccination) were asked whether or not they would pay all vaccination costs ranging from $360 to $500 for 3 doses of the vaccine, administrative cost, and the clinic visit. Responses included “yes” or “no”. Furthermore, those who responded “no” to this question (who were interested in vaccination but would not pay $360 to $500 for vaccination) or those who cited expense as the main reason for not vaccinating were further asked whether or not they would vaccinate their daughters if the vaccines cost much less or free. Responses included “yes” or “no”.

Demographic, socioeconomic, and preventive health behaviors covariates were also examined. Girls were categorized by their race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic, and others), region (northeast, Midwest, south, and west), highest education completed by a parent (<high school, high school graduate/general equivalency diploma, some college/college degree), family income according to percentage of the federal poverty line (<100%, 100% to <200%, ≥200%), and type of health insurance coverage (uninsured, public, and private). Preventive health behaviors such as a well-child check-up, dental examination, or influenza vaccine in the past 12 months were assessed by “yes or no” responses.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA 10 svy commands (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX) by taking into account survey weighting for the NHIS complex survey design, which consisted of multistage, stratified, and clustered samples. Probability sampling weights were used in conjunction with strata and primary sampling units (psu) to generalize the results to the population of 11-17 year old girls. Percentages and 95% confidence interval for HPV vaccine uptake of ≥ 1 dose and ≥ 3 doses were estimated by the age groups (11-12 years and 13-17 years), socio-demographic characteristics, preventive health behaviors, and the parental awareness about HPV vaccine. Estimation of vaccine series completion among those who initiated the vaccine was also stratified similarly. All estimates were weighted to girls aged 11-17 years.

Bivariate comparisons were assessed using chi square tests. We used multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine the association of race/ethnicity, highest education level of a parent, family income (% of federal poverty line), insurance coverage, preventive health behaviors and parental awareness about HPV vaccine with HPV vaccine receipt of ≥ 1 dose and ≥ 3 doses, and 3-dose vaccine series completion among girls who initiated the vaccine. Variables were screened for inclusion in the multivariate model. Candidate variables with P≤.20 with any dependent variable (uptake of ≥ 1 dose; uptake of ≥ 3 doses; and 3-dose series completion among girls who initiated vaccine) were included in the multivariate model.

Results

A total of 98.5% (2171/2205) of parents of 11-17 year old girls responded to the questions on HPV vaccination. Therefore, we restricted our analysis to these 2171 girls. Almost 29% and 14.2% of girls received ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses of the vaccine, respectively (Figure 1). About 49% of girls who initiated the vaccine (received ≥1 dose) completed the 3-dose vaccine series. Girls aged 16-17 years had the highest uptake of ≥1 dose (37.3%), ≥3 doses (20.2%), and 3-dose series completion among those who initiated the vaccine (54.1%). Girls aged 11-12 years were less likely than those 13-17 years to receive ≥1 dose (14.5% vs. 34.8%, P <.001) and ≥3 doses (3.0% vs. 18.7%, P <.001) of HPV vaccine. In addition, the 3-dose series completion among those who initiated the vaccine was significantly lower among the 11-12 years old age group than those13-17 years old (20.7% vs. 53.7%, P <.001).

Figure 1.

Estimated human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake of ≥1 dose, ≥2 doses and ≥ 3 doses among 11-17 year old girls (percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11-17 years).

Bivariate analyses of socio-demographic factors and HPV vaccine uptake showed that non-Hispanic Asian girls were significantly less likely than all other racial/ethnic groups to receive ≥1 dose of vaccine (Table 1). On the other hand, non-Hispanic whites were more likely than non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic girls to receive ≥3 doses of vaccine. No significant association between parental education levels and uptake of ≥1 dose of vaccine was observed, while parents with high school or some college/college degree were more likely than parents with less than a high school education to receive ≥3 doses of the vaccine. HPV vaccine uptake of ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses were significantly lower among uninsured than insured (public or private) adolescents and significantly higher among those with preventive health behaviors (well-child checkup, dental examination, and influenza vaccination in the past 12 months) as well as those with parents who were aware of the HPV vaccine. However, region and family income were not associated with uptake ≥1 dose or ≥3 doses. A separate bivariate analysis among girls who initiated the vaccine showed that non-Hispanic whites (P=.012), girls with private insurance (P<.001), girls with a family income >200% (P=.012), and girls who had a dental examination in the past 12 months (P=.029) were more likely to complete the 3-dose vaccine series compared to their counterparts (data not shown).

Table 1.

HPV vaccine uptake by characteristics among girls aged 11-17 years

| Factors | Total | Received ≥1 dose b | Received ≥3 doses b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=2171a | % (95% CI) | Pc | % (95% CI) | Pc | |

| Race/ethnicity | .047* | .004* | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 940 | 29.6 (26.2-32.9) | 16.1 (13.5-18.5) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 384 | 26.9 (21.6-32.3) | 10.9 (7.3-14.4) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 127 | 13.4 (7.6-19.2) | 6.2 (2.2-10.3) | ||

| Hispanic | 645 | 31.1 (26.5-35.6) | 12.3 (9.2-15.5) | ||

| Other d | 75 | 31.3 (19.5-43.0) | 15.4 (6.4-24.3) | ||

| Region | .972 | .458 | |||

| Northeast | 325 | 30.2 (24.2-36.2) | 17.4 (12.3-22.5) | ||

| Midwest | 434 | 28.0 (23.0-32.9) | 12.1 (8.6-15.7) | ||

| South | 797 | 30.4 (26.4-34.4) | 13.3 (10.6-16.1) | ||

| West | 615 | 26.7 (22.5-30.8) | 15.0 (11.7-18.3) | ||

| Parental highest education level | .112 | .013* | |||

| < HS | 350 | 25.4 (20.8-30.0) | 10.0 (6.8-13.2) | ||

| HS graduate/GED | 474 | 31.0 (26.8-35.2) | 14.8 (11.6-18.0) | ||

| Some college/college degree | 1154 | 31.1 (28.4-33.8) | 16.4 (14.2-18.5) | ||

| Family income (% of federal poverty line) |

.385 | .091 | |||

| <100% | 390 | 28.1 (22.7-33.5) | 9.0 (5.9-12.1) | ||

| 100% to <200% | 459 | 27.8 (22.9-32.7) | 12.0 (8.6-15.4) | ||

| ≥200% | 1127 | 30.1 (26.9-33.4) | 16.6 (14.0-19.2) | ||

| Unknown | 195 | 24.9 (17.3-32.5) | 14.1 (8.2-20.1) | ||

| Girl’s insurance coverage | <.001* | <.001* | |||

| None | 239 | 18.5 (12.3-24.7) | 6.0 (2.6-9.3) | ||

| Public | 731 | 31.6 (27.4-35.7) | 12.4 (9.6-15.2) | ||

| Private | 1197 | 29.1 (26.0-32.2) | 16.3 (13.9-18.8) | ||

| Well-child checkup in the past 12 months |

<.001* | .001* | |||

| Yes | 1561 | 31.5 (28.7-34.3) | 15.4 (13.3-17.5) | ||

| No | 594 | 21.6 (17.4-25.8) | 10.7 (7.7-13.7) | ||

| Dental examination in the past 12 months |

<.001* | <.001* | |||

| Yes | 1809 | 29.9 (27.4-32.5) | 15.3 (13.3-17.2) | ||

| No | 352 | 23.1 (17.4-28.8) | 7.6 (4.4-10.9) | ||

| Influenza vaccine in the past 12 months e |

<.001* | <.001* | |||

| Yes | 887 | 36.6 (32.7-40.6) | 17.8 (14.8-20.9) | ||

| No | 1279 | 22.8 (20.1-25.5) | 11.2 (9.3-13.2) | ||

| Parental awareness about HPV vaccine |

<.001* | <.001* | |||

| Yes | 1485 | 39.1 (36.1-42.1) | 19.1 (16.8-21.5) | ||

| No | 669 | 4.5 (2.6-6.4) | 2.1 (0.9-3.3) | ||

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11-17 years

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus; CI, confidence interval; HS, high school; GED, graduate equivalency diploma

Numbers do not add up to 2171 due to missing data

All values are based on row-percentage

Chi-square test was used (* P <.05 considered statistically significant)

Includes non-Hispanic American Indian Alaska Native, not releasable, and multiracial

Includes H1N1 and/or seasonal flu shot and/or nasal spray

Adjusted multivariate logistic regression models showed that Hispanic girls (P=.002), girls who received a well-child checkup (P=.028) or influenza vaccination (P<.001) in the past 12 months, and those with parents who were aware of the HPV vaccine (P<.001) were more likely to initiate ≥1 dose of the vaccine (Table 2). Characteristics positively associated with receiving ≥3 doses of vaccine were: having a dental examination (P= .040) or the influenza vaccine (P=.004) in the past 12 months, and parental awareness about HPV vaccine (P<.001). A separate multivariate analysis among those who initiated the vaccine did not identify any significant correlates of 3-dose series completion (data not shown), although race/ethnicity, insurance, income, and preventive dental exam showed a significant bivariate association.

Table 2.

Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake among girls aged 11-17 years

| Received ≥1 dose | Received ≥3 doses | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) a | OR (95% CI) a | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.92 (0.67-1.26) | 0.76 (0.51-1.13) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.78 (0.46-1.31) | 0.52 (0.25-1.07) |

| Hispanic | 1.59 (1.19-2.12)* | 1.11 (0.78-1.57) |

| Other b | 1.34 (0.74-2.43) | 1.32 (0.68-2.57) |

| Parental highest education level | ||

| Some college/college degree | Ref | Ref |

| HS graduate/GED | 1.04 (0.71-1.53) | 1.03 (0.64-1.68) |

| < HS | 0.92 (0.64-1.34) | 0.96 (0.60-1.54) |

| Family income (% of federal poverty line) | ||

| <100% | Ref | Ref |

| 100% to <200% | 1.06 (0.74-1.52) | 1.33 (0.84-2.10) |

| ≥200% | 0.78 (0.54-1.12) | 1.02 (0.63-1.64) |

| Unknown | 0.79 (0.48-1.29) | 1.21 (0.66-2.22) |

| Girl’s insurance coverage | ||

| None | Ref | Ref |

| Public | 1.38 (0.88-2.17) | 1.47 (0.78-2.77) |

| Private | 1.25 (0.79-1.96) | 1.81 (0.96-3.41) |

| Well-child checkup in the past 12 months | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.35 (1.03-1.75)* | 1.07 (0.78-1.48) |

| Dental examination in the past 12 months | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.20 (0.86-1.68) | 1.61 (1.02-1.54)* |

| Influenza vaccine in the past 12 months c | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.88 (1.51-2.33)* | 1.48 (1.13-1.92)* |

| Parental awareness about HPV vaccine | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 16.57 (10.95-25.06)* | 10.60 (5.95-18.88)* |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence interval; HS, high school; GED, graduate equivalency diploma

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used A bivariate predictor with a P value >.200 (region) was excluded from the multivariate model (* P <.05 considered statistically significant)

Includes non-Hispanic American Indian Alaska Native, not releasable, and multiracial

Includes H1N1 and/or seasonal flu shot and/or nasal spray

Nearly 71% of parents of 11-17 year old girls responded that their daughters were not vaccinated. About 60% of them were not interested in vaccinating their daughters or were unsure about it, if it was recommended. Common reasons were that they felt their daughters did not need the vaccine (25.5%), they had concerns about vaccine safety (19.3%), they had insufficient knowledge about the vaccine (16.6%), their daughters were not sexually active (11.2%) or were too young for the vaccine (6.4%), and that the vaccine was not recommended by their physician (5.5%). Only 1.2% reported expense as a barrier (Table 3). Parents without insurance were more likely to believe that their daughter did not need vaccination than parents with public/private insurance (P=.048). On the other hand, those parents with private insurance and a family income ≥200% were more likely to worry about vaccine safety than their counterparts (P=.048 and P <.001, respectively).

Table 3.

The main reason for not vaccinating among parents of unvaccinated girls (11-17 years) by insurance coverage and family income

| Insurance coverage c | Family income (% of federal poverty line) c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental main reason a | Total b | None | Public | Private | Pd | <100% | 100%-<200% | ≥200% | Unknown | Pd |

| n=910 | n=119 | n=271 | n=517 | n=160 | n=187 | n=458 | n=105 | |||

| Does not need vaccine, % |

25.6 | 37.4 | 26.4 | 23.3 | .048* | 29.7 | 30.0 | 21.6 | 28.8 | .157 |

| Worried about vaccine safety, % |

19.3 | 11.3 | 15.9 | 22.3 | .048* | 11.7 | 18.4 | 23.7 | 12.8 | <.001* |

| Do not know enough about vaccine, % |

16.6 | 15.5 | 19.5 | 15.4 | .159 | 22.0 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 18.8 | .122 |

| Not sexually active, % | 11.2 | 12.5 | 11.3 | 10.9 | .984 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 12.2 | 11.5 | .605 |

| Too young for vaccine, % |

6.5 | 0.7 | 6.1 | 7.4 | .033* | 5.0 | 2.7 | 8.3 | 7.8 | .362 |

| Doctor did not recommend, % |

5.5 | 5.2 | 7.0 | 4.8 | .758 | 9.7 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 6.1 | .032* |

| Too expensive, % | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | .100 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | .805 |

| Others,% e | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.5 | .441 | 8.7 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 2.7 | .246 |

| Do not know, % | 3.7 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 4.1 | .924 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 10.5 | .066 |

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11-17 years

All responses of the main reason were mutually exclusive

Includes unvaccinated girls whose parents were not interested in vaccination or responded “don’t know” to this information

All values are based on column-percentage and percentages do not add up to 100%

Chi-square test was used (* P <.05 considered statistically significant)

Includes don’t know about the place to get vaccine, spouse/family member against it, already has HPV, and other

About 39% of parents of unvaccinated girls would be interested in vaccinating their daughters in the future if it was recommended. Nearly 54% would agree to pay all costs for vaccination ($360-$500) while 42% preferred to receive the vaccine at a much lower cost or free, and 4% still would not receive the vaccine even if it was offered at a much lower cost or free. Parents with private insurance and a family income ≥200% of the poverty line were more likely to show their willingness to pay all costs for the vaccination ($360-$500) than their counterparts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Influence of insurance coverage and family income on vaccine cost among unvaccinated girls (11-17 years) whose parents were interested in vaccination

| Insurance coverage d | Family income (% of federal poverty line) d | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interested in vaccination | Total a | None | Public | Private | Pe | <100% | 100%- <200% |

≥200% | Unknown | Pe |

| n=576 | n=74 | n=211 | n=290 | n=109 | n=129 | n=303 | n=35 | |||

| Would pay if vaccination costs about $360-$500, b % |

53.7 | 41.2 | 41.0 | 63.9 | <.001* | 35.0 | 35.2 | 68.6 | 38.2 | <.001* |

| Would vaccinate if vaccine costs much less or free c , % |

41.7 | 50.1 | 56.0 | 31.6 | <.001* | 61.4 | 57.1 | 27.4 | 60.6 | <.001* |

| Would not vaccinate if vaccine costs much less or free c , % |

4.6 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 4.5 | <.001* | 3.6 | 7.7 | 4.0 | 1.2 | <.001* |

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11-17 years

Included unvaccinated girls (11-17 years) whose parents were interested in vaccination if recommended by a doctor

Included those parents of unvaccinated girls who were interested in vaccination and asked whether or not they would pay the vaccine cost about $360-$500

Included those parents of unvaccinated girls who were interested in vaccination but would not pay the vaccine cost about $360-$500 or for whom the main reason for not vaccinating was the expense and asked whether or not they would get the vaccine at a much lower cost or free

All values are based on column-percentage and percentages do not add up to 100%

Chi-square test was used to examine differences (* P <.05 considered statistically significant)

Discussion

Our analysis based on data from the 2010 NHIS showed that the overall rate of HPV vaccine uptake substantially increased among adolescent girls aged 11-17 years when compared with the 2008 NHIS report [21]. However, rates of receiving ≥1 dose showed little change among those 11-12 years old (14.5% vs.14.7%) and were a bit lower for ≥3 doses (3% vs. 5.5%). In contrast, those in the 13-17 year old group showed a higher uptake of both ≥1 dose (35% vs. 25%) and ≥3 doses (19% vs.11%). Therefore, higher uptake among 11-17 years old girls was attributed to the higher uptake among 13-17 year old group. This is in agreement with findings from the recent 2010 National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen data, which also reported higher HPV vaccine uptake among 13-17 year old girls [24]. The NIS reported that HPV vaccine uptake among girls aged 13-17 years has been increasing slowly since 2008 [22, 24, 25]: 37% and 18% of girls received ≥1 dose and ≥3 doses of the vaccine in 2008, respectively [22]. The respective numbers increased to 44% and 27 % in 2009 [25], and 49% and 32% in 2010 [24]. In fact, the vaccine uptake in the 2010 NIS study was higher than that observed in our study based on 2010 NHIS data. The discrepancies between these two nationally representative surveys could be due to differences in sampling methods, survey administration, or the accuracy of vaccine reporting [23, 26, 27]. NHIS-sample child module is an in-person household survey that represents households with or without landlines. This survey is possibly more representative sample of the general population, but it collects immunization information from parents on children ≤17 years of age based on their recall about the immunization [23]. In contrast, since 2006, NIS-Teen is a two phase survey: (1) random-digit-dialing telephone survey to identify household (with landlines) with eligible adolescent aged 13 to 17 years, and (2) a provider record check (PRC) for vaccination histories. Random-digit-dialed survey obtains vaccination receipt information and consent from parents to contact immunization provider(s) to verify immunization records. Thus, its reporting of immunization is more accurate [26].

Our finding that HPV vaccine uptake among 11-12 year old girls (recommended for routine vaccination) is lower than those13-17 years old is consistent with the NHIS 2008 report [21] and other studies conducted during 2007-08 [11, 13-15, 20, 28]. This scenario implies that vaccine uptake in the target age group has not been improving over the last few years. Many studies identified knowledge, attitude and practice of parents and providers as reasons for the differences in vaccination rates between 11-12 and 13-17 year old girls. For example, Kahn et al [29] showed that parents were more likely to vaccinate their older daughters than their younger ones. Providers also recommended the vaccine more frequently to older adolescents as they noted higher refusal rates among parents of 10-12 year olds [30, 31]. Thus, 11-12 year old adolescents experience more missed opportunities for vaccine administration than their older counterparts [15, 31]. This demonstrates the importance of educating parents about the benefit of administrating HPV vaccine before sexual initiation occurs when the vaccine is most effective [4-7].

Furthermore, the vaccine series completion rate among 11-17 year old girls who initiated the vaccine was higher [49%] in the 2010 NHIS study than that observed in 2008 (41%). This higher series completion rate was due to a higher rate among 13-17 year old initiators as the series completion rate among 11-12 year old initiators actually decreased from 37% to 21%. The reports based on NIS data also showed rapidly increasing vaccine series completion rates among those 13-17 years old girls who initiated the vaccine since 2008 [22, 24, 25]. In the 2008 NIS report, 48.6% of initiators completed 3-dose vaccine series. This number increased to 61.4% in 2009 and 65.3% in 2010. However, the persistence of low rates of 3-dose vaccine series completion among those 11-12 years old initiators is a matter of concern. Completion of all 3 doses has been labeled as essential for long term protection against HPV infections [32]. However, a recent study reported that 2 doses of bivalent HPV vaccine may produce a protective immune response similar to that of 3 doses [33]. The first dose may be administered at a routine preventive visit or a visit for another reason. After that, additional efforts from both providers and parents are needed to ensure that adolescents return for subsequent doses. Parents’ motivation, a positive attitude toward HPV vaccination, and financial resources are required for 3-dose series completion [34, 35]. Techniques which have been found to increase rates of vaccine series completion include reminding parents about its importance; using telephone, mail, or electronic reminders [32]; using a tracking system for scheduling the second and third doses [34]; and scheduling “immunization-only” appointments for the second and third doses [15].

In contrast to the 2008 NHIS study [21], we observed a higher uptake of ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine (initiation) among Hispanics than non-Hispanic whites. This is consistent with the recent report based on data from the 2010 NIS-Teen report and several other studies [13, 14, 22, 24]. Assistance from federally funded vaccine programs for those living below the poverty level could be responsible for this higher rate as the poverty level is higher among Hispanics than whites [22, 36]. On the other hand, several studies have observed a lower likelihood of vaccine series completion among Hispanic or black girls who initiated HPV vaccination than among whites in both bivariate [24, 25] and multivariate analyses [13, 32, 34, 37, 38]. We also observed similar findings based on our bivariate analysis. However, after adjusting for covariates, this racial difference disappeared. These findings are somewhat encouraging given the higher incidence of cervical cancer and mortality among black and Hispanic women than among whites [39, 40].

Several studies have observed that the Vaccine for Children [VFC] program eliminates socioeconomic disparities in vaccine initiation and labeled it as a major success for improving vaccine initiation among those living below poverty level [22, 24, 25, 35, 36]. This is in agreement with our study as well as studies based on 2008 NHIS [21] and 2010 NIS [24] data showed that vaccine uptake of ≥1 dose (initiation) did not differ by poverty status. On the other hand, the recent 2010 NIS [24] data showed that girls who initiated the vaccine living below the poverty level were less likely to complete the 3-dose vaccine series although this was not observed in the 2009 NIS study [25] or in our study. Thus, the benefit of the VFC program to eliminate socioeconomic disparities with regard to 3-dose series completion among initiators may not have been as consistent as it was for HPV vaccine initiation. Additional strategies for this purpose need to be examined because socioeconomically disadvantaged women are at high risk of cervical cancer [41].

Several population based national studies have reported a higher likelihood of vaccine initiation among insured girls than among uninsured [20, 21], which is consistent with our study [based on bivariate analysis]. However, only one study based on multivariate analysis observed a similar disparity [19]. In contrast, Dempsy et al [15] observed higher vaccine initiation among girls with public insurance than private or no insurance. In our study, the disparity between insured and uninsured girls disappeared after adjusting for covariates, which was expected since the federal VFC program covers uninsured and underinsured adolescents for this vaccine at no cost [36]. Also, we did not find any association between insurance status and 3-dose vaccine series completion among those who initiated the vaccine similar to a study based on 2008-2009 NIS data [35].

Our finding that preventive health behaviors (well-child check up or influenza vaccine in the past 12 month) are significantly associated with initiation (receiving ≥1 dose) of the HPV vaccine is consistent with the published literature [14, 15, 21, 28]. In addition, we found a significant association between these behaviors [dental examination or influenza vaccine in the past 12 month] and uptake of ≥3 doses of HPV vaccine among all girls. This association may be due to the parents’ overall attitude regarding preventive health services. Therefore, visits for other preventive healthcare may have a role in the increased uptake of the HPV vaccine.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, self-reported NHIS data from interviews may be subjected to recall bias. The data on vaccination status and number of vaccine doses were based on parental report and not confirmed by provider immunization records. Second, this survey did not collect data on the time periods between receipt of the first dose and subsequent doses, which limited our ability to evaluate whether the 3-dose vaccine series had been completed within the ACIP recommended time. Finally, cross-sectional survey data prevents our ability to infer causality from our analysis. Despite these limitations, this study serves the important purpose of examining recent uptake of HPV vaccine in young adolescents using a large nationally representative sample.

Nearly two-thirds of our study population remains unvaccinated. Furthermore, over half of the parents of unvaccinated girls do not intend to vaccinate their daughters. There is a concern because they will not be eligible to receive the vaccine for free through the VFC program after the age 18. Thus, additional educational programs are needed to increase parental awareness of HPV infection and its cancer risks, reduce negative attitudes toward vaccination, and provide much needed information about vaccination. In addition, providers should be encouraged to recommend the vaccine to their adolescent patients.

Acknowledgments

Federal support for this study was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) with two awards. Dr. Berenson is supported by a mid-career investigator award in patient-oriented research (K24HD043659, PI: Berenson). Dr. Tabassum Haque Laz is supported as an NRSA postdoctoral fellow under an institutional training grant (T32HD055163, PI: Berenson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- THL

Analysis and interpretation of data, Conception and design of the study, drafting the manuscript and approval of the final version.

- MR

Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript and approval of the final version.

- ABB

Conception and design of the study, revising the manuscript and approval of the final version.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- [1].Bosch FX, de Sanjose’ SS. Chapter 1: human papillomavirus and cervical cancer – burden and assessment of causality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;31:3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Garland SM, Steben M, Sings HL, James M, Lu S, Railkar R, et al. Natural history of genital warts: Analysis of placebo arm of 2 randomized phase III trials of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:805–14. doi: 10.1086/597071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moscicki A, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, Villa LL. Chapter 5: Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer. Vaccine. 2006;24S3:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR. 2010;59:626–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, Iversen OE, et al. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus like particle vaccine through 5 year of follow-up. Br J cancer. 2006;95:1459–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Romanowski B, de Borba PC, Naud PS, Roteli-Martins CM, De Carbalho NS, Teixeira JC, et al. Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 ASO4-adjuvanted vaccine: Analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial up to 6.4 years. Lancet. 2009;374:1975–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males-Advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR. 2011;60:1705–08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Jin Y, Huang B, Namakydoust A, Zimet GD. Rates of human papillomavirus vaccination, attitudes about vaccination, and human papillomavirus prevalence in young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1103–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817051fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Conroy K, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, Jin Y, Bernstein DI, Glynn S, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination. J Womens Health. 2009;18:1679–86. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT, Sternberg MR, Smith JS, Ziarnowski K, Liddon N, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:430–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, Meza HM, Loza ML, Short MB, et al. Uptake of HPV vaccine: Demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitude. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cook RL, Zhang J, Mullins J, Kauf T, Brumback B, Steingraber H, et al. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in Medicaid. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:596–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for human papillomavirus vaccination of adolescent girls and young women in a managed care organization. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:357–67. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Patient and clinic factors associated with adolescent human papillomavirus vaccine utilization within a university-based health system. Vaccine. 2010;28:989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Reiter PL, McRee A, Liddon N, Markowitz LE, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk geographic area. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:197–204. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f12dbf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Guerry SL, De Rosa CJ, Markowitz LE, Walker S, Liddon N, Kerndt PR, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk communities. Vaccine. 2011;29:2235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Caskey R, Lindau ST, Alexander GC. Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: Results of a national survey. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:525–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tylor LD, Harriri S, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2008. Prev Med. 2011;52:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wong CA, Berkowitz Z, Dorell CG, Price RA, Lee J, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 9- to 17-year-old girls: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Cancer. 2011;117:5612–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years- United States, 2008. MMWR. 2009;58:997–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].National Center for Health Statistics [Retrieved December 17, 2010];National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 2010. Public use data release: NHIS Survey Description. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2010/srvydesc.pdf.

- [24].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 through 17 years- United States, 2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1117–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years- United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59:1018–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jain N, Singleton JA, Montgomery M, Skalland B. Determining accurate vaccination coverage rates for adolescents: the National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:642–51. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Montgomery M, Khare M, Wouhib A, Singleton J, Jain N. Assessment of bias in the National Immunization Survey-Teen: benchmarking to the National Health Interview Survey. Abstract presented at: American Association for public Opinion Research Conference; New Orleans, Luisiana. May 15-18, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reiter PL, Cates JR, McRee AL, Gottlieb SL, Shafer A, Smith JS, et al. Statewide HPV vaccine initiation among adolescent females in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:549–56. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d73bf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kahn JA, Ding L, Huang B, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Frazier AL. Mothers’ intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1439–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, Black SR, Beaty BL, Barrow J, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: A survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126:425–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, Lee J, Quinn GP, Roetzheim R, et al. Missed clinical opportunities: Provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11-12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine. 2010;29:8634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Merck & Co [Retrieved December 17, 2010];A program to help improve patient compliance: 3 is key. 2010 Available at: http://www.merckvaccines.com/vaccines/gardasil/compliance_one.html.

- [33].Kreimer AR, Rodriguez AC, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Porras C, Schiffman M, et al. Proof-of-principle evaluation of the efficacy of fewer than three doses of a bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chou B, Krill LS, Horton BB, Barat CE, Trimble CL. Disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine completion among vaccine initiators. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:14–20. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318220ebf3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Niccolai LM, Mehta NR, Hadler JL. Racial/ethnic and poverty disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination completion. Am J Pev Med. 2011;41:428–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Retrieved December 17, 2010];Vaccines for Children: for parents. 2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/vaccines/programs/vfc/parents/default.html#eligible.

- [37].Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for completion of 3-dose regimen of HPV vaccine in female members of a managed care organization. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:864–70. doi: 10.4065/84.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Neubrand TP, Breitkopf CR, Rupp R, Breitkopf D, Rosenthal SL. Factors associated with completion of the human papillomavirus vaccine series. Clin Pediatr. 2009;19:411–16. doi: 10.1177/0009922809337534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McDougall JA, Madeleine MM, Daling JR, Li CI. Racial and ethnic disparities in cervical cancer incidence rates in the United States, 1992-2003. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:1175–86. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9056-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].National Cancer Institute [Retrieved December 17, 2010];SEER Stat Fact Sheets-Cancer of the Cervix Uteri. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html.

- [41].Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, Coughlin SS, Flowers L, Cokkinides V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008;113:2855–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]