Abstract

Consistent with Western cultural values, the traditional liberal theory of autonomy, which places emphasis on self-determination, liberty of choice, and freedom from interference by others, has been a leading principle in health care discourse for several decades. In context to aging, chronic illness, disability, and long-term care, increasingly there has been a call for a relational conception of autonomy that acknowledges issues of dependency, interdependence, and care relationships. Although autonomy is a core philosophy of assisted living (AL) and a growing number of studies focus on this issue, theory development in this area is lagging and little research has considered race, class, or cultural differences, despite the growing diversity of AL. We present a conceptual model of autonomy in AL based on over a decade of research conducted in diverse facility settings. This relational model provides an important conceptual lens for understanding the dynamic linkages between varieties of factors at multiple levels of social structure that shape residents' ability to maintain a sense of autonomy in this often socially challenging care environment. Social and institutional change, which is ongoing, as well as the multiple and ever-changing cultural contexts within which residents are embedded, are important factors that shape residents' experiences over time and impact resident-facility fit and residents' ability to age in place.

Introduction

Autonomy is a complex construct that has varying meaning and definitions in the literature. The liberal conception of autonomy, which has its roots in the liberal, moral, and political philosophies of the European Enlightenment, has been a fundamental principle in biomedical ethics and an ideal for care delivery in general for several decades. This mainstream view of autonomy, with its emphasis on independence, self-determination, and freedom from interference by others, also reflects central values in U.S. culture and is fundamental to ethical, social, and political discourse in many spheres of Western society (Atkins, 2006; Holstein, Parks, & Waymack, 2011). In context to aging, chronic illness, and disability, long-term care scholars have challenged this perspective for being too abstract and creating unrealistic expectations regarding individual independence (Agich, 2003; Holstein et al., 2011). Increasingly there has been a call for a relational conception of autonomy that acknowledges issues of dependency, interdependence, and care relationships (see for example Atkins, 2006; Agich, 2003; Holstein et al., 2011; Mackenzie & Stoljar, 2000; Small, Froggatt, & Downs, 2007).

In our earlier work (cf. Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review, 2005), we defined autonomy according to Hofland's (1990) conceptualization as encompassing two dimensions: (1) the psychological, referring to control over one's environment and choice of options and (2) the spiritual, relating to continuity in one's sense of personal identity over time and decision-making consistent with an individual's long-term values. We distinguished the concept of “autonomy” from “independence,” which we defined in terms of physical function and capacity for self-care. Consistent with our grounded theory synthesis approach (Wuest, 2000), an important goal of the current analysis was to build from previous work and construct theory with broader explanatory power. Our current relational approach expands on these earlier definitions while preserving the integrity, including the philosophical and epistemological underpinnings, of the primary studies.

The term “relational autonomy” does not represent a single unified theory, but instead denotes a grouping of related theoretical approaches that generally view personal autonomy in relation to the web of social and cultural contexts within which individuals are embedded (Mackenzie & Stoljar, 2000). Often described as having roots in feminist philosophy, scholarship in this area continues to grow and reflects insights from a wide range of academic fields and disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, nursing, bioethics, law, and public health. Consistent with a growing trend in modern healthcare and practice and the nature of gerontology itself, we adopt a multidisciplinary approach and draw inspiration for our study of relational autonomy in assisted living (AL) from these diverse but complementary perspectives.

A shared core concept in this expanding literature is the notion of the relational self. Prevailing views of the self in contemporary Western culture are of an independent and separate self-made individual. In contrast, a relational self is both individuated and interdependent and viewed as emerging out of relationships with other individuals, social groups, and institutions, which may either support or oppress one's opportunities for self-direction, self-discovery, and self-definition (Downie & Llewellyn, 2011; Meyers, 2000). Rather than conceiving of autonomy as freedom from constraint, a relational perspective views it in terms of identification, a process whereby individuals' sense of self is developed and (re)confirmed in context to daily interactions and experiences (Agich, 2003; Holstein et al., 2011). This perspective promotes a critical analysis of and response to conditions at the micro-, meso-, and macro levels that may diminish autonomy (Ellis, 2001; MacKenzie & Stoljar, 2001). It shines a light on particular societal conditions (social, economic, political and cultural), such as cultural prejudices and stereotypes about old age that threaten social justice and contribute to limitations imposed by disability (Kenny, Sherwin, & Baylis, 2010). Along these theoretical lines, autonomy is a product of structural relationships and social relations and occurs in context to unalterable social determinants, like race and socioeconomic status, and other conditions that may change over time, such as functional ability (Holstein et al., 2011; MacKenzie & Stoljar, 2001). A relational perspective attunes us to the possibility that, given the right social supports, individuals with significant physical or mental impairments may still exercise and maintain some degree of autonomy and, thus, retain selfhood (Small, Froggatt, & Downs, 2007).

Resident autonomy is a core philosophy of AL and research shows that residents place high value on this ideal (Ball et al. 2000; 2005; Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009; Morgan et al., 2006; Roth & Eckert, 2011) and the related concepts of independence (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell et al., 2004; Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Hollingsworth, et al, 2004) and privacy (Hawes, Phillips, & Rose, 2000). Despite a growing body of literature on autonomy in AL, we know of no known attempts to synthesize the knowledge that exists, limiting theoretical development in this area. In addition, few studies have considered race, class, or cultural differences, in spite of the growing diversity of AL (see Ball et al., 2005; Hernandez & Newcomer, 2007; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Combs, 2004 for exceptions).

The aim of the current study, which synthesizes and extends our earlier findings from over a decade of AL research, is to address current knowledge gaps and develop a theoretically-and empirically-grounded model of relational autonomy that is applicable across a range of AL settings (and potentially other care environments). We also contribute to the advancement of an innovative and underutilized analytical approach that integrates substantive findings from completed qualitative research to generate a more comprehensive understanding of health-related phenomena that may better inform policy and practice.

Assisted Living in the United States

Assisted living (AL) remains among the fastest-growing type of senior housing in the U.S. (Stevenson & Grabowski, 2010), with an estimated 39,500 facilities nationwide (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2009). AL facilities vary in size, structure, and levels and combinations of services and accommodations and typically do not provide skilled nursing care. State definitions of these non-medical residential care facilities vary and often reflect differences in regulations. Some state statutes differentiate between smaller mom and pop type facilities, often referred to as board and care homes or adult foster care facilities, and newer purpose-built facilities typically labeled AL (Mollica & Johnson-Lamarche, 2005). Although legislation recently passed in Georgia to create separate labels and licensing categories for these facilities, the Georgia statute currently uses the term “personal care home” broadly to include the full range of facility size and type. Here we use the term AL facility to be more consistent with common practice.

AL is largely a private pay industry with an estimated average annual private-pay rate of $37,572 (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2009). Smaller mom and pop type homes have much lower annual rates ($5,076–$18,000) (Ball et al., 2005; 2009). Forty-one states have some Medicaid financing for AL, but most public payments are low and serve a relatively small number of residents (Mollica, 2009). Most low-income disabled individuals only have access to smaller homes, which tend to be located in inner-city and rural areas and have lower trained staff and less family support (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2004).

Although AL serves a predominately-white clientele, recent research shows that the AL population is growing more diverse (Ball et al., 2005; 2009; Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, 2010). Demographic trends affecting all racial and ethnic groups, including smaller and geographically dispersed families, increased childlessness, and longer lives, are contributing to increased use of AL, including by African American and rural families, who have traditionally “cared for their own.” In addition to growing more diverse, AL is serving residents with greater physical and cognitive impairments more like those found in nursing homes (Golant, 2008; Ball et al., 2010). Dementia is prevalent with estimates ranging from 47% (Ball et al., 2010) to as high as 67.7% (Leroi et al., 2006). Recent data from a statewide study shows that the AL population in Georgia, the site of this study, resembles the national profile (Ball et al., 2010).

Methods

Research approach

This study involves a synthesis of substantive findings from both published and unpublished reports from three externally-funded qualitative projects conducted in Georgia between 1996 and 2002. All three projects used a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2008) and addressed aspects of autonomy in AL. Pre-existing analyses from published reports, outlined in Table 1, include five peer-reviewed journal articles and a peer-reviewed monograph. Other pre-existing analyses include two doctoral dissertations, key findings of which are published (Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review, 2005).

Table 1.

Reports included in the sample in order by year

| Author, Year | Facility Sample | Participant Sample | Data Source | Topical Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded for review et al., 2000 | 17 (2–75 bed) ALFs | 55 residents 17 providers | Project 1 | Residents' perceptions of quality of life in AL |

| Blinded for review et al., 2004 | 17 (2–75 bed) ALFs | 55 residents 17 providers | Project 1 | Meanings residents attach to independence |

| Blinded for review et al., 2004 | 1 small (13-beds) ALF | 18 residents 14 providers 3 family members | Project 2 | Risk-managing strategies low-income providers and residents use to maintain subsistence in AL |

| Blinded for review et al., 2004 | 5 (6–100 bed) ALFs | 39 residents 39 providers 28 family members/friends | Project 3 | Factors that shape residents' ability to age in place in AL |

| Blinded for review et al., 2005 | 6 (6–75 bed) ALFs | 104 residents 73 providers 24 family members/friends 8 community day program personnel | Projects 2 & 3 | In-depth exploration of the lived experience of African Americans in AL |

| Blinded for review et al., 2009 | 10 (6–100 bed) ALFs | 201 residents 73 providers 43 family members/friends 2 social workers | Projects 2 & 3 | How race and class influence decisions to move to AL and residents' ability to achieve resident-facility fit |

The initial grounded theory projects

Project 1 (1996–1997), conducted in 17 facilities, ranging in size from 2 to 75 beds, in three suburban Atlanta counties had a primary focus on how residents defined quality of life in AL (cf. Blinded for review, 2000). Most residents were white (99%), female (79%), and age 65 or older (93%). Monthly fees ranged from $750 to $2,953.

Projects 2 and 3, conducted between 1999 and 2002, focused on autonomy and independence with similar aims and research questions. Each had a sample of five homes. Compared to Project 1, homes and participants were markedly more diverse (see Table 2). Residents were almost evenly divided between blacks and whites. A higher-than-usually-reported percentage was under age 64 (15%) and male (30%), reflecting inclusion of small, low-income homes that served residents with mental illness. Four small (6–9 bed) homes participated in a Medicaid Waiver program.

Table 2.

Characteristics of sample ALFs in Projects 2 & 3

| Location | Race of Residents | Licensing Capacity | Years of Operation | Fee Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project 2 Homes | ||||

| Urban | All Black | 6 | 12 | $500–$800a |

| Urban | All Black | 6 | 20 | $500–$1,500 |

| Urban | 63% Black | 6 | 1 | $850–$l,000a |

| Urban | 55% Black | 13 | 16 | $430–$1,050 |

| Urban | All Black | 13 | 13 | $500-? |

| Project 3 Homes | ||||

| Rural Mountain | All White | 6 | 2 | $870–$l,500a |

| Small Town | All White | 9 | 12 | $870–$l,500a |

| Small Town | 98% White | 48 | 17 | $1,200–$2,000 |

| Urban | All Black | 53b (75)c | 1 | $2,095–$3,645 |

| Exurban | 94% White | 68b (100)c | 3 | $2,300–$5,650 |

Participant in Medicaid-waiver program.

Capacity of AL section.

Capacity including dementia unit.

Data collection methods across projects included in-depth interviews with residents and administrators and review of resident and facility records. Additionally, we conducted an inventory of the AL physical environment in Project 1 and informal interviews and participant observation in Projects 2 and 3. Consistent with a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2008), we used a constant comparative method to simultaneously collect, code, and analyze data. Additional information regarding sampling and study procedures, including adherence to university Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols are published elsewhere (see Table1).

Data analysis and synthesis

The current analysis is an extension of a qualitative synthesis approach we have used in previous research to integrate and synthesize findings across studies and develop substantive theory that has wider applicability (cf. Blinded for review, 2005; Blinded for review 2010). In addition to extending and refining earlier concepts, we continued to explore and develop new categories and subcategories using coding and memoing procedures consistent with grounded theory methods. In line with a “constant targeted comparison” method proposed by Sandelowski and Barroso (2007), analysis included making side-by-side comparisons of core categories, key processes and subprocesses, and conditions that emerged in our earlier studies (see Table 3). Analytical memos included diagrams, matrices, and charts to guide theory construction. We integrated findings and achieved consensus regarding emerging themes through weekly team discussion and periodic group coding sessions.

Table 3.

Side-by-side comparison of select study findings

| Blinded for review 2004 | Blinded for review 2004 | Blinded for review 2004 | Blinded for review 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic social problem | |||

| Preserving independent identity | Surviving economic and social marginality | Maintaining resident- facility fit | Negotiating ongoing change |

| Core Processes | |||

| Redefining independence | Negotiating risks | Managing decline | Maintaining sense of continuity while integrating change |

| Intervening Conditions (high ↔ low) | |||

| Sense of self-efficacy | Level of perceived risk | Aging-in-place capacity | Level of resiliency |

| Strategies/Subprocesses | |||

| Concealing impairment | Concealing impairment | Masking decline | Masking decline |

| Distancing through self-care | Enduring some deprivations | Preventing decline | Social distancing |

| Maintaining continuity of identity through self- care | Reframing stigmatizing situations | Responding to decline | Maintaining independent identity |

| Reciprocating for help | Negotiating for care and material needs | Relying on significant others for help with care | Maintaining sense of community and place |

| Lowering expectations | Defining current situation as best of available options | Defining current situation as better than the alternative | Miniaturization of autonomy |

As we refined our categories, we used theoretical sampling to link these with relevant concepts in the literature. These procedures are consistent with an iterative process used to elaborate existing theory known as “emergent fit” (Glaser, 1992; Wuest, 2000), which also serves to increase one's theoretical sensitivity as analysis continues. In selective coding, we reached the point of theoretical saturation and identified a central organizing process related to a core process, “balancing continuity with change,” identified in our earlier work (Blinded for review, 2003; Blinded for review 2005), which we labeled “maintaining the self in context to change.”

Findings

Maintaining the self in context to change: A theory of relational autonomy in AL

As Morse and Field (1995) note, a grounded theory generally serves to explain the basic social process through which individuals manage or resolve a basic social problem. In this study, coping with loss and managing associated threats to one's self concept emerged as the fundamental problem. Across studies, analysis shows that maintaining an authentic sense of self in the everyday world of AL is a constant struggle. Loss is a recurring theme in residents' accounts of their transition into AL and their ensuing lives. In addition to functional decline, residents cope with a multitude of social losses, including changes in social roles and status and the loss of loved ones through death, decline, and geographic separation. Additional threats to residents' self-concept include lack of privacy and adherence to both formal and informal rules. Similar to other group settings, the AL social environment often is competitive and characterized by cliques, gossip, and conflict. In small low-income homes, residents face additional challenges related to social and economic disadvantage. We also find that change in facility culture is inevitable and ongoing and over time can lead to a lack of resident-facility fit, which can compromise residents' quality of life and jeopardize their ability to age in place (cf. Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review 2005). Examples of social and institutional changes that affect facility culture and residents' aging- in-place capacity include staff and administrator turnover and residents' functional decline.

We find that residents' ability to cope with loss and associated threats to their self-concept is dependent on the quality of their relationships with others, as well as their ability to maintain a sense of continuity while also being open to and accepting change (Blinded for review, 2003; Blinded for review 2005). Based on our findings, we conceive of the self as continually evolving and including residents' current self-concept as well as past and future-oriented self-images. Residents construct and (re)confirm their sense of self in context to surrounding social life and changing circumstances based on their changing social situations and the meanings that they attach to the various situations that they encounter. How residents as a group react to and define their situations contributes to a shared sense of reality and in turn shapes facility culture. In many cases, we find that fear of decline or being labeled impaired, a situation which is both stigmatized and risky as it may lead to placement in a nursing home or dementia unit, contributes to certain negative aspects of the AL social environment that we (cf. Blinded for review, 2005) and others (see for example Dobbs, et al., 2008) have identified inside AL.

Intersecting factors that shape autonomy in AL at multiple levels

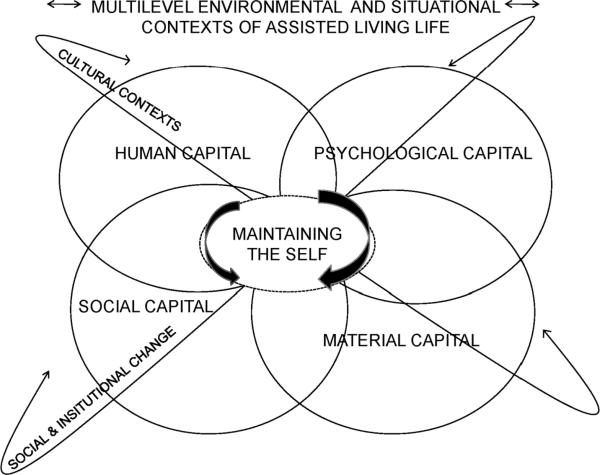

Through the process of emergent fit described above, we have extended earlier theory to incorporate four intersecting human conditions that we identify as key determinants of residents' ability to achieve autonomy, a reflection of the self, in AL. Drawing on Bourdieu's (1984;1986) notion of “capital,” we label these conditions in terms of four types of symbolic capital that have both objective and subjective properties: (1) material capital; (2) human capital; (3) social capital; and (4) psychological capital. According to Bourdieu's theory, the production of capital is socially constructed and relates to individual and shared meanings regarding what is valued within a culture or society. A central thesis of this relational approach is that all forms of capital, both material and nonmaterial, can have similar value and may be accumulated and converted from one form to another. Bourdieu posits that this process plays an important role in power relations, and the conversion of material capital to other nonmaterial forms largely hides sources of inequality. Within this conceptual framework, material capital is the most fundamental form of power. We acknowledge criticisms that conventional definitions applied to various forms of symbolic capital often judge individuals against a white, middle class norm (see Yosso, 2005) and include in our conceptual scheme cultural strengths and resources often overlooked in context to at-risk populations. Our conceptual model, shown in Figure 1, illustrates that, in the everyday world of AL, residents negotiate the self and strive for autonomy in context to a number of cultural features and in relation to ongoing social and institutional change. Consistent with a relational perspective, we conceptualize micro (individual residents and small groups), meso (individual facilities, local communities, and social networks), and macro (large-scale social systems and institutions, including aspects of the AL industry and regulatory system) levels of social organization as inherently connected and continually shaping one another through patterns of social interaction. Based on our findings, we describe the different components of our model below, including environmental and situational contexts that shape AL residents' experiences over time.

Figure 1.

Model of relational autonomy in assisted living

Environmental and situational contexts of AL life

We characterize the environment in terms of observable features that are potentially rateable or measurable, such as geographic location, use of space, and characteristics of the resident population. We distinguish between this domain and that of culture, which we conceive of as a process that emerges out of group norms, values, and behaviors. Situational contexts include both the situated (objective) contexts of residents' lives as well as the ways in which they defined the various situations that they encountered. Both as a group living within a particular facility culture and as individuals, residents attached different meanings to their situations based on factors, such as race, class, culture, life history, and functional ability (cf. Blinded for review, 2003; Blinded for review, 2005).

How residents defined their initial move into AL, including the role they had in the decision to move, often shaped adjustment to subsequent change (cf. Blinded for review, 2005; 2009. Residents' reactions to this transition ranged along a continuum from embracing change to denying or resisting it (Blinded for review, 2003). After a period of adjustment, many residents accepted the transition as a necessary, albeit often not welcome, change. Some viewed AL residence as temporary, an illusion sometimes fostered by family members, a deceptive strategy that sometimes backfired and harmed family relationships. One resident said, “If I can get well, I can go home.” Others developed a more fatalistic outlook, as conveyed in the following statement, “I don't look forward to anything. I think very little about the future. I live day-to-day and expect it to end up very shortly. In fact, I hope it does.” Such residents often viewed their lives as meaningless, regardless of opportunities for control and choice in daily life. Perceptions of staff and others in the AL environment often contributed to residents' fatalistic outlook. One staff member's view of her caregiving role, although well intentioned, is instructive: “This is their last cycle. They are [close to] death and dying. I can make a difference when they are getting ready to step over that line.”

For many residents, having an environment consistent with their personal history and identity was a key factor in their ability to adapt to AL life and maintain a positive sense of self. A resident of a rural mountain home said, “I can see the woods. I grow'd up in the mountains, so I love it here.” Although he viewed himself as intellectually superior to his fellow “inmates,” whom he actively avoided, another resident said that he valued his “all-African American” facility where the décor, meals, and activities reflected African American culture and residents had class backgrounds similar to his. This upscale urban setting provided him with a sense of belonging that he would not have felt living in “a mixed place.” Diverse populations, including residents from different age groups, race and cultural backgrounds, and functional abilities, however, characterized several low-income homes. Two homes that served frail older adults also included several younger residents with serious mental illness

Finding a facility located in their former communities was important to multiple residents. Often most meaningful was having access to activities in the community, including in churches, senior centers, and day programs, as well as connections with former friends and neighbors (cf. Blinded for review, 2005). In several cases, close relationships that developed inside AL grew out of past community connections, such as having lived in the same neighborhood or attending the same church or mental health program.

Several homes in this study were located in low-income and racially segregated communities. Municipal services in these areas often were substandard and crime rates tended to be high. In addition to crime and other safety risks, such as abandoned dogs running loose, physical features of these low-income areas, including cracked and broken sidewalks, heavy traffic, and a lack of streetlights and pedestrian signage, which limited the ability of some frail residents to get out into the community. When we asked a 60-year-old resident who had relocated from an unlicensed home in a heavier crime-ridden area of town what mattered most at this stage of his life, he said, “Being able to walk down the street in my neighborhood without a fear of getting knocked in the head when I step off my doorstep.”

Some residents created meaningful environments within their individual rooms with furnishings and personal effects from their former homes. A resident in a large suburban home indicated that his personal belongings helped eased his transition into AL and provided him with a feeling of continuity and a sense of place. He said, “I was leery at first [about the move], but after I got to bring my furniture I felt much better about it 'cause I feel at home with my things.” As noted by others (Rubenstein, 1987; 1989; Rubenstein & de Medeiros, 2005), such personal objects, often imbued with meaningful ties to the past, can be important vehicles through which vulnerable older adults hold onto and express valued aspects of their self following environmental transition.

Because of lack of private space, residents living in small low-income homes typically lacked the option of bringing personal furniture. Although modest, some low-income homes were quite homelike. Others had few personal touches or amenities, such as the communal clothes closet and black and white television with rabbit ears that characterized one. For residents of these homes safety and security often was most important. A resident of a small urban facility who relocated from public housing described her newfound sense of security, “It's a safe place here. You don't hear nobody cussing and drunk at night.”

When describing AL, many residents used descriptors such as “institution” or “care home,” but few defined this setting as “home,” even though many indicated some level of “at-homeness.” Within our culture, the construct of “home” is an important symbol of the self, which often carries emotional meaning and represents intimate ties and significant life events (Rubenstein & de Medeiros, 2005; Blinded for review, 2005). Although most residents indicated a desire to age in place in AL, consistent with Frank (2002), we found that many key aspects residents associated with “home” were missing. We also found that the unwillingness of some to equate the AL environment with “home” was one of many strategies residents used to distance themselves from the stigma they associated with being an AL resident.

Maintaining the self

Throughout this paper, we identify a number of other strategies residents used to maintain a positive sense of self. One way some residents coped was to reframe certain negative aspects of their situation. A new resident stated, “[The facility] is like a college dorm. I have to sign out when I leave. You have to adjust to the idea. It is not a bad idea. It is a good idea that somebody is watching out for you.” Similar to other AL research (Roth & Eckert, 2011), we found that many expressions of autonomy in AL, while important to residents' identity, often were subtle and not immediately obvious. One resident who distanced himself from other more “helpless” residents through self-care, boasted, “Downstairs they give out the pills, but I'm handling my own.” Drawing on Rubenstein and his colleague's (1992) concept of “minituarization of satisfaction,” we refer to this form of autonomy work in terms of “redefining independence” and “minituarization of autonomy” (Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review, 2005), processes whereby residents scale down their expectations and assign greater value to what little control and remaining functional ability they do have. Another common strategy residents used to maintain the self was managing decline, which included concealing decline. Tactics residents used to conceal decline included social isolation, shunning needed assistance and assistive devices, and using memory aids, for example, a newspaper with handwritten cues jotted across the front page that one resident used as a prop.

In some cases, certain forms of identity maintenance, such as social distancing and gossiping, posed threats to residents' self-concept. Residents' ability to respond to such threats and cope with adversity depended largely on their stock of personal resources, which we describe here in terms of four interacting and overlapping forms of capital.

Material capital

In all sizes and types of homes, to some extent, material capital, which includes financial assets and material possessions, shaped residents' autonomy, including access to meaningful relationships and activities in and out of the home. Material capital, often symbolized by factors, such as the way residents dressed and type of suite they could afford, also provided a basis for social comparison and acceptance in several facilities. The influence of material capital on residents' autonomy was most evident in the low-income homes, where race and socioeconomic status limited residents' initial choice of where to live, amenities, access to recreational activities, and opportunities for privacy (cf. Blinded for review, 2005). One resident who shared a room with tw0 other men described his inability for “alone time”: “When I don't feel like being bothered with somebody, I still be bothered with 'em.”

Despite many shortcomings, several residents living in low income homes defined their current situation as the best of available options or better than the alternative. One resident said, “I don't believe I can live no better.” Another described his facility as “better than being out on the street or in a homeless shelter.” In many cases, we found that a history of disadvantage mitigated residents' difficulty adapting to vagaries of these environments, a coping response Goffman (1961) referred to as “immunization.”

Human capital

The literature typically defines human capital as a combination of individual attributes, such as knowledge, training, education, personality, talent, and skills, which enable one to achieve status and material wealth. We include in this definition residents' physical and mental functional capacity, as well as their physical appearance, socially valued assets that, similar to material wealth, provided a basis for social comparison and acceptance in many facilities. A history of discrimination and poverty contributed to a higher rate of chronic disease, including mental illness, among residents in low-income homes and limited their access to human capital (Blinded for review, 2004; Blinded for review, rate 2005). Some residents had creative talents or skills, such as quilting or poetry writing, that were self-affirming and helped a few gain facility recognition and status. In some cases, residents had personal attributes, such as physical attractiveness or sense of humor that helped compensate for deficits in other areas, including cognitive decline.

Social capital

Similar to autonomy, definitions of social capital vary by academic discipline, level of investigation (i.e., individual versus community), and how the construct is operationalized. Generally, social capital refers to personal resources and status defined by group membership and social and interpersonal ties.

Within AL, we find that access to social capital often hinges on prior connections residents or their families had with residents or providers and on aspects of material or human capital, such as social class or physical attractiveness. Maintaining function frequently is essential to sustaining social status or capital. A staff member in an upscale home described a common scenario, “Here you have to [continue to] prove that you are still independent and socially acceptable.” In the same home, where blacks were in the minority and many white residents still harbored ingrained racist attitudes, one 102-year-old African American was able overtime to overcome racial stigma and even achieved a level of celebrity status. In addition to being the first and only centenarian in the facility, she was well-dressed, college-educated, and as one resident said, “[did not] have a wrinkle on her face.”

Most residents valued family relationships above all others and those with supportive family relationships often were best equipped to cope with challenges of AL life. Many residents living in low-income homes had little or no access to family and drew strength from family-like ties they had with significant others in the community or fictive kin (CF. Blinded for review, 2005). Residents lacking meaningful ties to people from their past often had the most difficult time maintaining a sense of continuity and adapting to inevitable changes in facility culture.

Psychological Capital

Similar to previous work by two of the current authors focusing on home care (Blinded for review, 1995:42), we found that in the absence of material resources and other types of assets, psychological resources, which we conceptualize here in terms of “capital,” enabled some residents to maximize what few resources they did have and “pull through.” This form of capital, which includes religious faith and spirituality, hope, optimism, resilience, and a sense of self efficacy, arises out of inner strengths within the self that allow residents to persevere.

Often, we found that residents who were most resilient to loss and other threats to identity were those who over their life course had developed strengths and coping skills to deal with adversities, such as homelessness, poverty, discrimination, and long-term disability or illness. For example, several residents who attended community mental health programs reframed these activities as “work” or “school” to be consistent with mainstream values. A 65-year-old long-term participant in the mental health system spoke of one day “retiring.” Religiosity and spirituality also contributed to the ability of many residents to maintain a sense of self efficacy and hope. Important cultural strengths we identified among resident subgroups, including minority group members and rural residents, included racial/ethnic pride and a sense of collective history, tradition, and community. This sense of group identity (a form of social capital) included bonds developed among residents who were more marginal, such as ties developed “on the street” or through involvement in the mental health system (cf. Blinded for review, 2005).

The differing experiences of two residents exemplify the complex interplay between psychological capital and other forms of capital and help illustrate how their combined effects shape residents' ability to maintain an authentic sense of self in AL. One resident with a large private suite in an upscale facility described her future as “a matter of waiting to die,” despite having relatively good physical health and cognitive ability. She relocated from the northeast to be near family and described her status as that of “a foreigner” and “dirty Yankee.” In contrast, a resident who shared a room with three other women had significant physical impairment and was poor and without family expressed optimism about the future: “I'll just live a happy life until I leave it.” Cultural strengths of this resident, who grew up African American in the rural South, included a strong religious faith and a valued identity as a survivor. She said, “Don't many people live to get 92.” In the challenging AL environment, we found that residents' ability to maintain ties with significant others, which could include God, and to draw upon personal talents and strengths often was essential to maintaining a viable sense of self, regardless of the social capital they held inside a facility.

Cultural Contexts

Global, national, state, and regional culture shape AL culture at the macro level. At the global level, increasing globalization and outsourcing of jobs has had a negative influence on local economic conditions in some communities where AL facilities are located, particularly in the rural south, and continues to contribute to the growing diversity of the AL workforce (Ball et al., 2010; Browne & Braun, 2008; Redfoot & Houser, 2005). At the national level, AL facilities are embedded in U.S. culture, which emphasizes personal autonomy, independence, and self-determination, cultural values often at odds with residents' reality. (Carder, 2002; Carder & Hernandez, 2004; Eckert et al., 2009). The AL industry's emphasis on consumer choice and control is another example of this “paradoxical conjunction” (Agich, 2003:1), where residents as “consumers” typically move to AL based on need or a crisis and often have little choice or control in the decision to move, the selection of a facility, and daily routines, which are subject to regulatory constraints and rules designed to manage and negotiate risks associated with functional impairment (Ball et al., 2005; 2009; Carder; 2002; Carder & Hernandez, 2004; Eckert et al., 2009). Although many aspects of AL culture such as these are similar across states, AL culture varies somewhat at the state level based on differences in how facilities are financed, labeled, and regulated. Regional and geographic differences further contribute to cultural differences found inside facilities.

In the studies we present here, the unique facility culture of each home formed the primary backdrop against which residents strived to maintain a coherent sense of self. The culture of the wider community, including the distinct culture of surrounding neighborhoods, also shaped facility culture, as did community-level social capital, which included facilities' reputation in the community and support, or lack of, from neighbors, community groups, and local organizations. In one gentrifying community, neighborhood groups actively worked to close small low-income homes, contributing to the marginal status of residents and providers. A provider describes experience:

Within the last two years when the area start to develop for the better, [the neighborhood association] was questionable about my being here and sent peoples out to do the inspection of my home, you know, the zoning department men, because {the neighbors} wanted me to leave.

Subgroups and cliques also were an important aspect of facility culture. Characteristics of these groups included shared backgrounds, status, abilities, and even conflicts. In an upscale facility, where having dementia carried marked stigma, a clique formed among a small group of cognitively impaired female residents who passed time poking fun at passersby in the lobby, including other residents, staff, and even family members. In some facilities, cliques based on former occupations or social class often mirrored previous community positions, for example, members of Atlanta's black elite. Examples of subgroups in low-income homes included younger mentally ill residents and those with a history of homelessness and involvement in mental health programs whose networks encompassed members of the surrounding street culture, including local prostitutes and panhandlers.

Although cliques and subgroups provide some residents with social capital, they contributed to the exclusion and marginalization of others. Despite the efforts of providers in some small homes to select residents who fit well with the culture of their homes, all homes included residents viewed by the larger collective as outsiders, misfits, or troublemakers. Often, residents formed bonds along lines of commonality and those in the minority were marginalized. Examples included the one white female living in a predominately African American inner-city home and the only African American in a facility located in the small town where she had been a longtime resident, who complained of overt racial discrimination and lamented, “There's nothing like being with your own [race].” Often, lack of connection to the local community or to southern culture contributed to marginalization. Residents with dementia gained acceptance as valued members of the collective in some small family-like homes, compared with larger facilities where having this condition typically carried a stigma.

As we have noted, disability and decline, especially related to mental impairment, were key factors that contributed to stigma and social exclusion, findings consistent with a previous classic study of nursing home life (Gubrium, 1975) and research conducted in other types of older adult congregate housing, including AL (Dobbs et al., 2008; Fisher, 1990). Across studies, we observed that many residents commonly distanced themselves from others perceived as socially unacceptable to avoid being stigmatized by association. This protective strategy often included gossiping and engaging with other residents in critical evaluation of prior friends or tablemates who had experienced decline. In some cases, residents distanced themselves by becoming “loners” or developed relationships with staff. One resident said, “I don't have many friends, [but] I do very well.” Sometimes, this distancing behavior included promoting conflict or engaging in other behaviors that fellow residents found offensive, such as the deliberate act of one resident to extinguish his cigarette wherever he sat.

Helping behavior was a more positive characteristic of facility culture and a strategy residents used to “minimize the stigma of disability and [maintain] feelings of normalcy” (Blinded for review, 2004: 473). In the absence of other recreational activities perceived as worthwhile, helping was a meaningful way residents found to pass the time and have valued roles and social interactions. In several small, low-income homes, residents' involvement in facility chores was common and a meaningful activity. Chores included growing vegetables, caring for facility pets, and helping with meals. In all homes, residents helped co-residents, including pushing wheelchairs and reminding about meals. Such helping was another way higher functioning residents distinguished themselves from those perceived as less fortunate. In some cases, resident support masked need for additional staff help (cf. Blinded for review, 2004).

Social and institutional change

Ironically, we found that residents who were most committed to their lives in AL often had the greatest difficulty preserving meaning owing to inevitable change in facility culture. Residents' functional decline, changes in family support, loss of outside friends, and altered dynamics within facility social circles contributed to facility culture change. Findings from Projects 2 and 3, where we conducted observations over time, showed that other key factors that lead to culture change include facilities' economic difficulties, changes in staffing or the resident population, and providers' personal problems. Increased AL competition and economic fluctuations were important community factors linked with these facility changes, findings consistent with other recent AL research (see for example Eckert et al., 2009).

Changes we observed over 12-to-18 months included the corporate merger of two facilities, renovations and expansions in two others, conversion of private rooms to shared space, and changes to admission and discharge policies. Such transitions altered facilities' social and, in several cases, physical environments. To fill empty beds, one small home provider, whose previous residents were elderly females, began admitting younger mentally ill male residents. An upscale home's admission of residents with increased impairments, to counteract a census drop, led to a nursing-home-like environment at odds with the values of current residents. In an all-African American upscale home, pressure to fill beds prompted consideration of marketing to whites, a move that stood to adversely affect residents who valued its African American culture. A corporate representative stated: “We have promised investors a specific return on their investment. It is an all-African American home today. It might not be tomorrow.” Similarly, owners of a small rural home, who had a side business sanding floors to make ends meet, described expansion plans that stood to disrupt the family-like environment that residents valued: “The people here [in this community] don't have any money, especially the old people. There is a lot of competition too now. We need to get bigger to make a living.”

We found that to survive economically, providers, the primary agents responsible for social and cultural change inside AL, continually weighed facility needs and constraints against the needs of residents and their family members, staff, and, in the small homes, providers' own families. Level of perceived risk was an important intervening condition that shaped their business actions and strategies. Difficult decisions include deciding whether to terminate dedicated staff to accommodate census drops or to discharge a beloved resident in decline. Providers' personal values regarding caregiving helped shape these decisions, as did their commitments to supporting their own families. In contrast to most providers who emphasized economic success, one elderly operator “called” to caregiving by God, often placed her residents' needs above her own, a strategy that ultimately led to the closing of her home. Elsewhere, we have described such decision-making as “a process of negotiating risks” (Blinded for review, 2005; Blinded for review, 2004; 2010).

Discussion

The model of relational autonomy in AL we propose (Figure 1) provides an important conceptual lens for understanding the dynamic linkages between a variety of factors at multiple levels of social structure that shape residents' self-concept. This model views autonomy, an expression of the self, as a process that individual residents experience and define differently against a broad backdrop of environmental and situational contexts that may either promote or hinder self-realization. Important components of this model include its dynamic conceptualization of the self, which acknowledges the influence that one's past and future selves has on one's current self-concept, as well as our expanded notion of symbolic capital, which recognize cultural strengths and resources possessed by members of minority groups and other at-risk populations that conventional definitions overlook. Also key is our attention to mechanisms of social and institutional change, as well as the multiple and ever-changing cultural aspects within which residents are embedded, important factors which shape their experiences over time and impact their ability to age in place. How residents react to and define their ever-changing situations in turn contributes to the nature of facility culture. Thus, in addition to its focus on resident autonomy, this model illuminates mechanisms through which both positive and negative aspects of AL life may develop.

Our relational model is informed by a synthesis of more than ten years of qualitative research in diverse AL settings. These findings show that adapting to life in AL is an ongoing process marked by change, loss, and difficult life transitions related to the debilitating effects of chronic illness and loss of independence. Consistent with earlier research (Charmaz, 1983; 1997), our research shows that coping with such threats to one's self concept may result in a diminished sense of control over life and negative expectations regarding the future, attitudes found to pose serious health risks (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Schnittker & McLeod, 2005). Thomas and Thomas's (1928) classic concept of “definition of the situation” posits that what individuals define as real is real in its consequences, a position our findings support. Residents with more fatalistic views often indicated that their lives held little meaning, regardless of opportunities some had for choice and control, and some had lost the will to live. Our findings show that hope is a key factor in residents' ability to maintain a sense of autonomy in context to loss and other negative changes that threaten their self-concept. Identity theorists maintain that significant and generalized others have an important influence on these future expectations (Markus & Nurius, 1986; Rosenberg, 1981), another theoretical supposition supported by our findings.

Across our studies, race, class, and cultural background influenced the degree of control residents had, including their choice of AL setting, and were salient aspects of residents' identity that, for some, also served as protective factors in their ability to adapt. Although evidence of this type of psychological capital was prevalent across studies, it did not characterize all residents with a history of disadvantage. Our findings indicate that other forms of capital (material, human, and social) and certain aspects of the social and physical environment, such as a facilty's resident profile and location, may either promote or hinder certain individuals' ability to draw upon these cultural strengths, findings that call for further study. We also found that some environments lacking in material resources had other positive elements associated with them, such as cultural or biographical significance or community-level social capital that seemed to mitigate deficits in other areas.

Increasingly, place has shown to have an important impact on health and identity (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2000; Kawachi & Berkman, 2003; Leith 2006; Rowles & Ravdal, 2002; Rubenstein & de Medeiros, 2005). Related research has focused on the meaning of place within AL (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell et al, 2004; Cutchin, 2003; Cutchin et al., 2003; Frank, 2002). Some findings indicate that the salience of place and its influence on health and identity increases with age, particularly as life's challenges increase (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2000; Rowles & Ravdal, 2002; Rubenstein & Medeiros, 2005). Within the AL environment, the risk of nursing home placement is a key challenge that residents and their families face (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell et al., 2004). Across studies, we found that fear of decline or of being labeled impaired, especially cognitively, often motivated residents to engage in a form of impression management (Goffman, 1959) whereby they disassociated themselves from others who threatened their identity. Researchers have identified this form of identity work among other individuals in marginal circumstance, such as the homeless (Farrington & Robinson, 1999; Snow & Anderson, 1987). Ironically, we found that this protective strategy contributed to the marginalization and stigmatization of others, resulting in a circular process that reinforced the stigma associated with impairment and decline and continued to promote fear among residents. Other negative outcomes included residents' development of strategies to hide impairment, such as self-isolation and shunning needed assistance and assistive devices. As also noted by others (see for example Dobbs et al., 2008) and implicit in our relational model, the stigma within AL is linked with societal attitudes toward disease, old age, and dependence. Completely eradicating such stigma and its associated fear will require social and institutional change, including challenging current stereotypes and promoting more positive images of older people and other marginalized populations. These results also suggest the need for interventions that give residents something to forward to and anticipate, such as meaningful recreational activities. Consistently we find that facilities gear activities toward lower functioning residents, a practice that contributes to their stigma and limits the options of higher functioning residents for meaningful encounters. Also important is keeping residents better integrated into the outside community, either assisting them to get out or encouraging others to come in. Because of some homes' marginal community status and residents' general lack of access to community programs, community support poses a challenge for many facilities that will require outreach and education.

Our research also shows many positive outcomes associated with the AL environment. Consistent with past research (Golant 2011; Rowles & Ravdal, 2002), our findings show that residents' ability to maintain a connection, either physically or vicariously, with past places in their lives was an important source of biographical continuity, a core dimension of the self-concept. In several cases, close relationships that developed inside AL grew out of past community connections, such as having lived in the same neighborhood or attending the same church or mental health program. Another important basis of continuity, which included having access to meaningful activities and relationships both inside and outside the facility, was having an AL environment consistent with one's past and identity. In many cases, residents gained a sense of place and maintained a feeling of continuity by engaging in “place-making,” (McHugh & Mings, 1996; Rowles & Ravdal, 2002), which included transporting personal belongings from home and carrying out a process we have referred to as “community-building” (cf., Blinded for review 2005). Drawing on various forms of capital accumulated over time, we found that many residents actively sought, and often found, a sense of place and of autonomy in the AL setting. “They … adapted to life there not as some isolated incident but as part of their ongoing life story” (Blinded for review 2005:57).

Conclusion

Gaining theoretical understanding of residents' behaviors and subjective experiences within the sociocultural context of AL is important to creating services and designing interventions that are effective and accepted by stakeholders. Our proposed model, which is grounded in findings from our own studies and supported by insights from others' research, is an important step toward building theory regarding autonomy in AL, an area where theoretical development is lagging. This research also contributes to the advancement of qualitative research synthesis, an analytical technique that has important potential for expanding the scope of knowledge gained from individual qualitative studies, which can better inform policy and policy but to date has been underutilized. Our qualitative synthesis and model of relational autonomy in AL provides a conceptual roadmap that can help us begin to deconstruct factors at multiple levels of social structure that interfere with resident autonomy and raise consciousness among policy makers, providers, and family members regarding ways various social determinants shape residents' everyday lives.

In several states, including Georgia, efforts are underway to change existing AL regulations to address the growing impairment level of residents, including increasing numbers of residents with dementia. Proposed regulatory changes in Georgia include language that many aging advocates fear will further contribute to the marginalization of small facilities and affect providers' ability to survive economically (Aging Services of Georgia, 2011), contributing to health disparities noted to exist among this resident population (Ball et al., 2005; Hernandez & Newcomer, 2007; Perkins et al., 2004). Our model and findings provide a critical framework that can inform important policy debates in Georgia and other states, including the need for additional public financing for AL.

Our model and qualitative synthesis also inform a growing body of literature promoting a relational view of the self in context to people with dementia (for a review see Small et al., 2007). Consistent with a relational approach, Small and his colleagues note that selfhood of people with dementia, like all other people, is constructed and shaped through interactions with others, including how situations, such as dementia, are defined. A relational perspective makes us alert to the possibility that individuals with dementia and other significant functional limitations may still exercise some degree of choice consistent with their personal values and remaining capacities and abilities, given the right social supports, including those at individual, facility, community, and societal levels.

Our proposed conceptual model has several strengths, but it is not without limitation. Although it expands the scope of insights gained from qualitative studies carried out in diverse AL setting over more than a decade, this theory emerges from data collected in one southern state in the United States. Therefore, it may not reflect regional differences that exist. Nonetheless, a strong suit of this analytical approach is that we can continue to build on and confirm or discount these findings as we synthesize them with new data, including studies by other researchers. As such, this research is an important first step in a theory-building process that to date has been limited.

Highlights

In context to aging, chronic illness, disability, and long-term care, we contribute to a relational view of autonomy.

Our relational model informs policy, practice, and research in an area of health where theoretical development is lagging.

We address race, class, and cultural differences among residents in assisted living, an increasingly diverse care setting.

Our conceptual model is applicable to a diverse range of residential care settings for older adults.

We contribute to the advancement of qualitative synthesis, an innovative, but underutilized, analytical technique.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [R01AG16787-01A1]; the AARP Andrus Foundation; and the Gwinnett, Rockdale, Newton Counties Regional Board of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse. We gratefully acknowledge the residents, staff, and family members who participated in the research. Additionally, we extend thanks to Drs. Elisabeth O. Burgess and Malcolm P. Cutchin for their valuable comments on prior drafts of the manuscript. Our acknowledgements would not be complete without thanking the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback which informed the final draft of the conceptual model and contributed to the overall quality of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agich GJ. Dependence and autonomy in old age: An ethical framework for long-term care. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aging Services of Georgia SB 178: Creation of assisted living communities and use of the term “assisted living”. 2011 [White paper]. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins K. Autonomy and autonomy competencies: A practical and relational approach. Nursing Philosophy. 2006;7:205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Whittington FJ, King SV. Pathways to assisted living: The influence of race and class. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28:81–108. doi: 10.1177/0733464808323451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Connell BR, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Elrod CL, Combs BL. Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S202–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.s202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004;18:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted Living for African American Elders. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ. Surviving dependence: Voices of African American elders. Baywood Publishers; Amityville, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson VL, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of judgment of taste. Routledge; London: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press; Westport, CT: 1986. pp. 242–258. [Google Scholar]

- Browne CV, Braun KL. Globalization, women's migration, and the long-term care workforce. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:16–24. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC. The social world of assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2002;16:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, Hernandez M. Consumer discourse in assisted living. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S58–S67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Loss of self: A fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1983;5:168–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz KC. Good days, bad days: the self in chronic illness in time. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, New Jersey: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz KC. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide to qualitative analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cutchin MP. The process of mediated aging-in-place: A theoretically and empirically based model. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutchin MP, Owen SV, Chang PJ. Becoming at home in assisted living residences: Exploring place integration processes. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S234–S243. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Eckert JK, Rubenstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski AC, Zimmerman S. An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:517–526. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie J, Llewellyn J. Being relational: Reflections on relational theory and health law and policy. University of British Columbia Press; Toronto, Ontario: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C. Lessons about autonomy from the experience of disability. Social Theory and Practice. 2001;27:599–615. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington A, Robinson WP. Homelessness and strategies of identity maintenance: A participant observation study. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 1999;9:175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BJ. The stigma of relocation to a retirement facility. Journal of Aging Studies. 1990;4:47–59. + [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick K, LaGory M. The ecology of risk in the urban landscape: Unhealthy places. Routledge; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frank JB. The paradox of aging in place in assisted living. Bergin & Garvey; Westport, CT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence Vs. Forcing. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients. Doubleday Anchor; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. The future status of assisted living residences: A response to uncertainty? In: Golant S, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future (3–45) Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. The quest for residential normalcy by older adults: Relocation but one pathway. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium JF. Living and dying at Murray Manor. St. Martin's Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Phillips CD, Rose M. High service or high privacy assisted living facilities, their residents and staff: Results from a national survey. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Newcomer R. Assisted living and special populations: What do we know about differences in use and potential access barriers? The Gerontologist. 2007;47:110–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.supplement_1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofland B. Why a special focus on autonomy? Generations. 1990;14(Supplement):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein MB, Parks JA, Waymack MH. Ethics, aging, and society. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhood and Health. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny NP, Sherwin SB, Baylis FE. Re-visioning public health ethics: A relational perspective. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2010;101:9–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03405552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leath KH. “Home is where the heart is… or is it?”: A phenomenological exploration of the meaning of home for older women in congregate housing. Journal of Aging Studies. 2005;20:317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi I, Samus Q, Rosenblatt A, Onyike C, Brandt J, Baker A, Rabins P, Lyketsoset C. A comparison of small and large assisted living facilities for the diagnosis and care of dementia: The Maryland Assisted Living Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;22:224–232. doi: 10.1002/gps.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, editors. Relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Nurius PS. Possible selves. American Psychologist. 1986;41:954–969. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh KE, Mings RC. The circle of migration: Attachment to place in aging. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1996;86:530–550. [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute . The 2009 Metlife market survey of nursing home, assisted living, adult day services, and home care costs. Westport, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DT. Intersectional identity and the authentic self. In: Mackenzie C, Stoljar N, editors. Relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R. State Medicaid reimbursement policies and practices in assisted living. National Center for Assisted Living (NCLA) and American Health Care Association; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R, Johnson-Lamarche H. State residential care and assisted living policy: 2004. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LA, Eckert JK, Piggee T, Frankowski AC. Two lives in transition: Agency and context for assisted living residents. Journal of Aging Studies. 2006;20:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Combs Finding meaning in assisted living: Maintaining continuity while integrating change. The Gerontologist. 43(Special Issue 1):36. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Combs BL. Managing the needs of low-income board and care residents: A process of negotiating risks. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:478–495. doi: 10.1177/1049732303262619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Sweatman WM, Hollingsworth C. Co-worker relationships in assisted living: The influence of social network ties. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2010. pp. 124–146. [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot D, Houser A. We shall travel on: Quality of care, economic development, and the international migration of long-term care workers. AARP Public Policy Report; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. The self-concept: Social product and social force. In: Rosenberg M, Turner RH, editors. Social psychology: Sociological perspectives. Basic Books; New York: 1981. pp. 593–624. [Google Scholar]

- Roth EG, Eckert j. K. The vernacular landscape of assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.005. doi 10.16/j.jaging.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles GD, Ravdal H. Aging, place, and meaning in the face of changing circumstances. In: Weiss R, Bass S, editors. Challenges of the third age: Meaning and purpose in later life. Oxford University Press; New York: 202. pp. 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein RL. The significance of personal objects to older people. Journal of Aging Studies. 1987;1:225–238. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(87)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein RL. The home environments of older people: a description of the psychosocial processes linking person to place. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1989;14:S45–S53. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.2.s45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein RL, Kilbride JC, Nagy S. Elders living alone: Frailty and the perceptions of choice. Aldine De Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein RL, de Medeiros K. Home, self, and identity. In: Rowles GD, Chaudhury H, editors. Home and identity in late life. Springer Publishing Company, Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Company, Inc.; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, McLeod JD. The social psychology of health disparities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Small N, Froggatt K, Downs M. Living and dying with dementia: Dialogues about palliative care. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DA, Anderson L. Identity work among the homeless: The verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92:1336–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Sizing up the market for assisted living. Health Affairs. 2010;29:35–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas W, Thomas S. The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. Knopf; New York: 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J. Negotiating with helping systems: An example of grounded theory evolving through emergent fit. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10:51–70. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosso T. “Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity, and Education. 2005;8:69–91. [Google Scholar]