Abstract

Previous research has found that a speaker’s native phonological system has a great influence on perception of another language. In three experiments, we tested the perception and representation of Mandarin phonological contrasts by Guangzhou Cantonese speakers, and compared their performance to that of native Mandarin speakers. Despite their rich experience using Mandarin Chinese, the Cantonese speakers had problems distinguishing specific Mandarin segmental and tonal contrasts that do not exist in Guangzhou Cantonese. However, we found evidence that the subtle differences between two members of a contrast were nonetheless represented in the lexicon. We also found different processing patterns for non-native segmental versus non-native tonal contrasts. The results provide substantial new information about the representation and processing of segmental and prosodic information by individuals listening to a closely-related, very well-learned, but still non-native language.

Keywords: sibling languages, non-native language processing, segmental versus tonal perception, lexical representation of L2 contrasts

Infants are born with an ability to discriminate phonological contrasts in all languages (Streeter, 1976). However, over the course of the first year of life, perception of native speech (L1) greatly improves while that of non-native speech significantly declines (Kuhl et al., 2006, Werker & Tees, 1984). This perceptual specialization for native sounds continues to develop into adolescence (Iverson et al. 2003). Related research has focused on the perception of contrasts in a second language (L2) or in a non-native dialect, at both segmental and prosodic levels. Several theoretical models have been proposed to explain why adults experience difficulties in perception and learning of non-native segments, including Flege’s Speech Learning Model (Flege, 1995, 1999, 2003) and Best’s Perceptual Assimilation Model (Best, McRoberts, & Goodell, 2001; Best & Tyler, 2007).

Flege’s Speech Learning Model (SLM) suggests that first and second language sounds exist in a common phonological space and interact with each other. According to SLM, L2 learners can establish new L2 phonetic categories if they detect phonetic differences between an L2 sound and the nearest L1 sound. Thus, the more similar a new L2 category is to the nearest L1 category, the more difficult it is for an L2 learner to establish a new L2 category. For instance, Japanese speakers are well known to have difficulties in learning English /ɹ/ and /l/ (Goto, 1971; Guion et al., 2000; Hattori & Iverson, 2009; Miyawaki et al., 1975). However, Japanese speakers acquire the English phoneme /ɹ/ more successfully than they acquire English /l/ (Aoyama et al., 2004), because English /l/ is more similar than English /ɹ/ to the closest Japanese phoneme (Guion et al., 2000).

Best’s Perceptual Assimilation Model (PAM) also assumes that listeners have a strong tendency to assimilate a non-native speech category to the most similar native category. In this model, there are three ways that a given non-native sound could be perceptually assimilated to the native phonological system. It can be perceived as an exemplar of a native category, as an uncategorized segment that is similar to two or more native categories, or as a nonspeech sound that cannot be assimilated. According to PAM, if the two sounds of a non-native contrast can be assimilated to two different native categories, or if one sound of a non-native contrast is categorized while the other is not, discrimination should be fairly good. If the two sounds of a non-native contrast are assimilated to the same native category or fall in between the same native categories, discrimination will generally be poor. If the two sounds are assimilated to a single native category with different goodness of fit, discrimination will be moderate. In support of this view, Japanese speakers were better at distinguishing English /ɹ/-/w/ than English /ɹ/-/l/ (Best & Strange, 1992; Guion et al., 2000) because the former contrast is a goodness difference case, while the latter is a single category case. Although Japanese speakers are inclined to rate English /l/ as being somewhat more similar to the closest Japanese phoneme than English /ɹ/ (Aoyama et al., 2004), they are both poor exemplars of the same Japanese category (Best and Strange, 1992; Hattori & Iverson, 2009). Therefore, even highly experienced Japanese (L1)-English (L2) bilinguals still have difficulty in discriminating this contrast (Guion et al., 2000).

In the current study, we examine the perception of L2 Mandarin contrasts by native speakers of Guangzhou Cantonese. Cantonese and Mandarin have overlapping but different sets of vowels, consonants, and lexical tones, providing a natural setting to compare segmental contrasts to tonal contrasts. In addition, Cantonese speakers get intensive education in Mandarin beginning at the early age of six, which allows an investigation of highly experienced L2 listeners. Our study includes both phonological and lexical level tests. To foreshadow, there are interesting similarities and differences between segmental and tonal processes, and between phonological and lexical levels of representation.

In tone languages, the same syllable with different lexical tones will have diverse meanings. For instance, despite having the same segmental components, the Mandarin words /mⱭ(1)/(“

”, meaning mother), /mⱭ(2)/ (“

”, meaning mother), /mⱭ(2)/ (“

”, meaning flax), /mⱭ(3)/ (“

”, meaning flax), /mⱭ(3)/ (“

”, meaning horse) and /mⱭ(4)/ (“

”, meaning horse) and /mⱭ(4)/ (“

”, meaning scold) have totally different meanings (the number after each syllable indicates the syllable’s lexical tone).

”, meaning scold) have totally different meanings (the number after each syllable indicates the syllable’s lexical tone).

Our experiments took advantage of differences in the segmental and lexical tone inventories of Cantonese and Mandarin. At the segmental level, one of the biggest differences involves fricatives and affricates. Cantonese has only two affricates and one fricative: /ts/, /ts′/ and /s/, while Mandarin consonants include /ts/, /ts′/, /s/, /tʂ/, /tʂ′/ /ʂ/, /tɕ/, /tɕ′/, and /ɕ/. At the prosodic level, the Cantonese tone system is more complex than the Mandarin system: Guangzhou Cantonese has six tone patterns plus shortened versions of three of these (Zhan et al., 2004), while Mandarin has only four tones (Hallé, Chang & Best, 2004; So, 2005a, 2005b). Using a standard 5-level pitch scale (in which 5 represents a high pitch, and 1 a low pitch, so that a 51 tone would start high and end low), Cantonese tones have pitches of 55/53 (there is variability in the ending pitch across speakers), 21/11, 35, 13, 33, 22 and short versions of 55, 33 and 22. Mandarin tones have pitches of 55, 35, 214 and 51, which are usually referred to as Tones 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Due to these differences, there are contrasts in Mandarin that do not exist in Cantonese, at both the segmental and prosodic levels. We will be testing how native Cantonese speakers deal with such contrasts.

In the literature there are very different views on whether Cantonese and Mandarin are two different dialects of Chinese, or are two different languages. Some researchers have argued that they are two different languages (Cai, Pickering, Yan, & Branigan, 2011; Chen et al., 2004; Francis, Ciocca, Ma, & Fenn, 2008) because they are largely (but not entirely) mutually unintelligible. However, others consider them to be two dialects of Chinese because of lexical, syntactic, and orthographic similarities (Lee, Vakoch, & Wurm, 1996; Tang & van Heuven, 2009; Zhan, Li, Huang, & Xu, 2004; Zhang, 1998). In a lecture given in 1945, the Yiddish linguist Max Weinrich said (translated to English) that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy. This description nicely captures the differing opinions with regard to Cantonese and Mandarin, with Mandarin and Cantonese officially considered as two dialects of Chinese by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Xing, 1991).

For our purposes, it is sufficient to note that if they are different languages, as the difficulties in mutual intelligibility would suggest, they are certainly closely related ones. We believe that it is useful to look at studies of L2 processing in terms of whether the native and non-native cases are, like Cantonese and Mandarin, sibling languages. In this spirit, we will refer to closely related languages, including these two, as “siblangs” (sibling languages), to make it clear that the results pertain to pairs that include significant overlap at the lexical and syntactic levels. Results for siblangs may or may not turn out to match those for distant pairs, such as English and Japanese.

Given that we will be testing native Cantonese listeners on non-native (Mandarin) segmental and tonal contrasts, and examining the impact of these factors on lexical processing, we will briefly review prior findings in these domains:

The perception of non-native segmental contrasts

Many researchers have examined the perception of non-native consonantal and vocalic contrasts, with the most widely studied case being the one we have already mentioned: the poor performance of Japanese speakers in discriminating English /ɹ/ and /l/ (Goto, 1971; Guion et al., 2000; Hattori & Iverson, 2009; Miyawaki et al., 1975). Even after several weeks of perceptual training, Japanese speakers typically show only a small (though significant) improvement in distinguishing this contrast (Bradlow et al., 1997; Lively, Logan, & Pisoni, 1993; Lively et al., 1994; Logan, Lively, & Pisoni, 1991). Similarly difficult cases include Italians trying to distinguish some vocalic contrasts (e.g., /e/-/ε/, /i/-/ɪ/) in Canadian English (Flege & MacKay, 2004) and American English speakers trying to discriminate French /y/-/ø/ (Gottfried, 1984).

There have been a number of studies of Spanish-Catalan bilinguals that provide a particularly useful context for our study because Catalan and Spanish are also siblangs. Moreover, as with our Guangzhou listeners, the second language is learned early and used widely. A somewhat surprising finding is that even fluent non-native language speakers may have difficulty perceiving segmental contrasts in their L2. Proficient Spanish (L1) – Catalan (L2) bilinguals fail to distinguish certain Catalan phonemes that do not exist in Spanish, such as /e/-/ε/ and /s/-/z/ (Pallier, Bosch, & Sebastián-Gallés, 1997; Pallier, Colome, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2001; Sebastián-Gallés & Soto-Faraco, 1999; Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverria, & Bosch, 2005; Sebastián-Gallés, Rodríguez-Fornells, de Diego-Balaguer, & Díaz, 2006). Even simultaneous bilinguals, who had been exposed to both Spanish and Catalan from birth, have problems in perceiving segmental contrasts that do not exist in their dominant language (Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverria and Bosch, 2005). Flege and MacKay (2004) have suggested that an early age of L2 acquisition may not guarantee native-like perception of L2 phonemes – only those who learn L2 at an early age and also use their native language less frequently may reach similar perceptual levels as native speakers.

The perception of non-native tonal contrasts

An important difference between the Catalan-Spanish case and ours is the role of lexical tones in Mandarin and Cantonese; Romance languages such as Catalan and Spanish do not use lexical tones. Prior work has shown that speakers whose native language is non-tonal have difficulty perceiving the tones of a tonal language. Some cases that have been examined include the perception of Mandarin words by English speakers (Bent et al., 2006; Gottfried & Suiter, 1997), by Uigur speakers (Gao, 2005), or by French speakers (Hallé et al., 2004), and the perception of Thai words by English speakers (Burnham et al., 1996).

More germane to the current study is the finding that if a speaker’s native language is tonal, this can influence the perception of non-native tones. For instance, both Cantonese speakers (Burnham et al., 1996) and Mandarin speakers (Wayland & Guion, 2004) were better at distinguishing Thai tones than English speakers, and training significantly helped the Mandarin speakers but not the English speakers. However, there have been some conflicting findings, suggesting that prior experience with a tonal language may not necessarily aid the acquisition of tones in another language. For example, Hmong speakers, whose native language has seven tones, performed worse than Japanese speakers and English speakers in identifying the four tones in Mandarin (Wang, 2006).

There is a small existing literature on tone perception in siblangs – Mandarin and Hong Kong Cantonese (which has six tones -- 55/53, 35, 33, 21, 22, and 23; Zhan et al., 2004). Francis et al. (2008) examined Mandarin speakers’ identification of Hong Kong Cantonese tones and compared it with English speakers. The two groups showed similar performance on identification before training, and English participants actually made greater progress on some of the Cantonese tones after training. So (2005a, 2006a, 2006b) tested Hong Kong Cantonese participants’ discrimination of Mandarin tones and found that they were poor at identifying some of the Mandarin tones, despite their native familiarity with lexical tones.

The representation of minimal pairs of words

Compared to the large literature on the perceptual difficulties associated with non-native phonetic contrasts, there has been much less research focused on how these perceptual problems affect word recognition. There have been three approaches to this issue. One approach is to obtain lexical decision judgments for “near words” – tokens in which a phoneme that does not exist in the listener’s native language is replaced by a similar one that does exist. For example, for native Dutch speakers listening to English, a word like “task” (which includes the vowel /æ/ that is not in the Dutch inventory) could be presented as “tesk” (with the closest Dutch vowel, /ε/). Under such conditions, Dutch speakers are much more likely to misidentify English nonwords as words than English speakers (Broersma, 2002). Similarly, Spanish (L1) – Catalan (L2) bilinguals were much more likely than native Catalan participants to erroneously identify (as words) Catalan nonwords that had been produced by substituting the Catalan phoneme /e/ (present in Spanish) for Catalan /ε/ (not a Spanish vowel) (Sebastián-Gallés et al., 2005).

The second approach used to study non-native lexical processing employs a priming methodology, and tests whether minimal pairs of words containing ambiguous contrasts are represented as homophones for non-native speakers. For example, Spanish (L1) – Catalan (L2) subjects showed repetition priming for minimal pairs of Catalan words (e.g. /netə/-/nεtə/) differing in contrasts that do not exist in Spanish (e.g. /e/-/ε/), whereas Catalan L1 participants showed repetition priming only when the same word was repeated (Pallier et al., 2001). Because there were no comparable priming effects for nonword stimuli, Pallier et al. demonstrated that the repetition priming paradigm specifically targets lexical effects. The repetition priming for Spanish-dominant bilinguals suggests that the non-native sound (/ε/) is represented in the lexicon as the native sound (/e/), making minimal pairs homophonous.

However, evidence from the third approach -- eye-tracking -- suggests that there may be differences in the lexical representations for words containing native versus non-native sounds. For example, Japanese participants were more likely to look at a picture of a locker when they were asked to click on the picture of a rocket than the reverse (Cutler, Weber, & Otake, 2006). Similarly, Weber and Cutler (2004) found competition from words with the native Dutch sound /ε/ for targets with the non-native /æ/, but not vice-versa. Due to these asymmetries, the eye-tracking results are difficult to accommodate with the notion of lexical representations that are identical for words with native versus non-native segments. In the current study, we will use a version of the priming methodology that allows us to look for such asymmetries, a test that has not generally been available in priming studies.

The present study

In the current study, three experiments were conducted to test how Guangzhou Cantonese speakers, who learn Mandarin beginning in primary school, perceive and represent consonantal and tonal contrasts that are present in Mandarin Chinese but not in their native Cantonese. We examine how early learners of a siblang perceive and represent segmental and prosodic contrasts that do not exist in their native language, and what ramifications these differences have for word recognition. Experiment 1 uses a discrimination task to measure how well the Cantonese listeners can discern differences between non-native Mandarin contrasts. Using segmental and tonal contrasts that have been established as difficult, Experiment 2 uses an implicit perceptual processing task to determine whether the members of the non-native contrasts are treated as equivalent sounds when they are not the focus of the task. Finally, in Experiment 3, we use a priming task similar to that of Pallier et al. (2001), but with additional procedures that allow us to look for the kinds of perceptual asymmetries that have been seen using eye-tracking approaches. This addition is the key to examine whether the perceptually difficult non-native contrasts are nonetheless represented differentially in the lexicon. In all three experiments, we test both segmental contrasts and prosodic (tonal) ones.

Experiment 1

The goal of Experiment 1 was to identify specific Mandarin consonants and tones that are difficult for Cantonese native speakers to discriminate, to provide a basis for stimulus selection in the following experiments. Thus we chose 12 pairs of consonantal contrasts formed by 9 Mandarin consonants (i.e., /ts/-/tʂ/, /ts′/-/tʂ ′/, /s/-/ ʂ/, /ts/-/tɕ/, /ts/-/tɕ′/, /ts/-/ɕ/, /ts′/-/tɕ/, /ts′/-/tɕ′/, /ts′/-/ɕ/, /s/-/tɕ/, /s/-/tɕ′/, and /s/-/ɕ/) and 6 pairs of tonal contrasts formed by the four Mandarin tones (i.e., T1–T2, T1–T3, T1–T4, T2–T3, T2–T4 and T3–T4). The frequency of each of these Mandarin consonants and tones is provided in Appendix A. We used an oddity discrimination paradigm developed by Flege and MacKay (2004) to determine the most difficult Mandarin consonant and tone contrasts for native speakers of Cantonese.

Method

Participants

Thirteen Guangzhou native Cantonese speakers (mean age of 22 years, ranging from 21 to 25 years) and 13 native Mandarin speakers (mean age of 24 years, ranging from 22 to 26 years) participated in this experiment. The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers were born and raised in Guangzhou and began learning Mandarin in primary school (about six or seven years old). Their average experience using Mandarin was 16 years, ranging from 14 to 19 years. They usually communicate with their teachers and classmates in Mandarin in class, but speak Cantonese outside class. The Mandarin speakers were born and raised in areas where Mandarin is the native dialect (e.g. Beijing and Chengde). During subject recruitment, participants were informed that we were testing native Cantonese or native Mandarin speakers. All participants were tested in the Cognitive Language Lab in Huazhong Normal University in China. No participant reported any hearing problem, and all received small gifts for their participation.

Stimuli

The stimuli for consonant perception were monosyllabic words created by combining the tested consonants with the vowel [▪] and Mandarin Tone 1. This procedure yielded 12 minimal pairs of words differing only in their consonants (although the vowel after /tɕ/, /tɕ′/, and /ɕ/ is pronounced slightly differently from that after the other tested consonants). The stimuli for tone perception were monosyllabic words created by combining the syllable /pⱭ/ with four Mandarin tones, yielding six minimal pairs of words differing only in tones. Words were recorded by three female Mandarin native speakers. All stimuli were digitized (44.1kHz) and edited with GoldWave 5.22 sound editing software. Appendix B lists the words used in this study.

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a sound-attenuated booth. On each trial, three words produced by different speakers were presented sequentially. Three-fourths of the trials were change trials, containing an odd item that differed in either consonant, such as /ts ▪ (1)/-/tʂ ▪ (1)/-/ts ▪ (1)/, or tone, such as /pɕ(1)/-/pɕ(1)/-/pɕ(2)/. The odd item occurred with equal frequency in all three possible positions in the series, and each contrast was tested in 12 change trials. The remaining 1/4 of the trials were no-change trials, containing three identical words that had been produced by different speakers, such as /ts ▪ (1)/-/ts ▪ (1)/-/ts ▪ (1)/ and /pɕ(1)/-/pɕ(1)/-/pɕ(1)/. Change trials were used to investigate participants’ sensitivity to different phonological categories, while no-change trials were used to make sure that variation within a single category (speaker-based variation) was ignored by participants.

The experiment was controlled by a Lenovo computer running Windows XP. Stimuli were presented via headphones at a comfortable listening level using E-prime 1.1 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.) software. On each trial, three items were presented sequentially with an ISI (inter stimulus interval) of 1s. Participants were told to decide which was the odd item and to press the key labeled “1”, “2,” or “3” corresponding to the position of the odd item in the series. If all items were the same, they were told to press the fourth key, labeled “4”. They were asked to make decisions as quickly and as accurately as possible. A subsequent trial began 750ms after the participant had responded. If a participant failed to respond within 3000ms, a new trial would start.

The experimental phase was divided into two blocks. In one block, participants were instructed to focus on consonant changes and only the minimal pairs differing in the consonant were presented. In the other block, participants were instructed to focus on tone changes and only the minimal pairs differing in the tone were presented. Each block was preceded by a practice. Twelve trials were included in the practice before the consonant block started and ten trials were included in the practice before the tone block started. All of the critical contrasts in the experiment were tested in the practice and no feedback was given. The order of the two blocks was counter-balanced across participants, and the order of trials within each block was random.

Results and Discussion

Data from trials in which participants failed to respond within 3000ms were discarded (2.4% of all responses).

Accuracy analysis

An A′ score was calculated for each contrast as a measure of how discriminable the two members of the contrast were. The A′ score is based on the proportion of hits and false alarms. A hit was defined as the correct selection of the odd item on a change trial, and a false alarm was defined as the report of an odd item on a no-change trial; Appendix C shows the hit and false alarm rates used to compute A′. An A′ score of 1.0 reflects perfect discrimination of a contrast, while an A′ score of 0.5 corresponds to a chance level of performance (see Flege & MacKay, 2004; Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverria & Bosch, 2005; Sebastian-Gallés et al., 2006; Sebastián-Gallés et al., 2009; Snodgrass, Levy-Berger, & Haydon, 1985).

Consonant discrimination accuracy

Figure 1 shows the two groups’ A′ scores for each consonantal contrast. A 2 (Group: Guangzhou Cantonese vs. Mandarin) × 12 (Consonant Type: 12 consonantal contrasts) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on A′ scores for the consonantal contrasts. The main effect of Group was significant, F(1,24)=5.52, p=.027, η2=.19, with the mean A′ of Guangzhou Cantonese speakers significantly lower than that of Mandarin speakers (.90 vs. .96). The main effect of Consonant Type was also significant (F(11,264)=3.67, p<.001, η2=.13), ranging from an average score for the two groups of .90 for the /ts/-/ɕ/ contrast to an average of .96 for the /s/-/tɕ′/ contrast, p<.001. The interaction between Group and Consonant Type also reached significance, F (11,264)=1.94, p=.035, η2=.08, indicating that some contrasts were more difficult for the Cantonese speakers (compared to the Mandarin speakers) than others. Simple effect tests demonstrated that the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers’ scores were lower than the Mandarin speakers’ for six consonantal contrasts: /ts/-/tʂ/ [F(1,24)=6.11, p=.021], /ts′/-/tʂ′/ [F(1,24)=9.41, p=.005], /s/-/ʂ/ [F(1,24)=8.54, p=.007], /ts′/-/tɕ/[F(1,24)=5.53, p=.027], /ts′/-/tɕ′/ [F(1,24)=6.33, p=.019], and /ts′/-/ɕ/ [F(1,24)=7.92, p=.010]. Of these, the /ts/-/tʂ/ contrast produced the largest average difference in absolute A′ scores, and the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast produced the most reliable difference in performance between the Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, making these two contrasts the best candidates for further study.

Figure 1.

Mean A′ scores (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for 12 Mandarin consonantal contrasts by the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in Experiment 1.

Tone discrimination accuracy

Figure 2 shows the two groups’ A′ scores for each tonal contrast. A 2 (Group: Guangzhou Cantonese vs. Mandarin) × 6 (Tone Type: 6 tonal contrasts) mixed analysis of variance was conducted on the A′ scores for tonal contrasts. The main effect of Group was not significant, F(1,24)=1.05, p=.316, η2=.04. The main effect of Tone was significant, F(5,120)=2.93, p=.016, η2=.11. The average score for the T1–T2 contrast was significantly lower than that for the T1–T3 (.94 vs. 96) and T2–T4 (.94 vs. 96) contrasts, p<.05. The average score for the T2–T3 contrast was significantly lower than that for T2–T4 contrast (.94 vs. .96), p<.05. The interaction between Group and Tone Type did not reach significance, F (5,120)=1.88, p=.103, η2=.07, though the T2–T3 contrast clearly showed the largest separation between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Mean A′ scores (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the six Mandarin tonal contrasts by the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in Experiment 1.

Reaction time analysis

Consonant discrimination reaction times

Table 1 shows the reaction times for each of the consonant contrast cases. A 2 (Group: Guangzhou Cantonese vs. Mandarin) × 12 (Consonant Type: 12 consonantal contrasts) mixed analysis of variance was conducted on reaction time for the consonantal contrasts. The main effect of neither Group nor Consonant Type was significant, F(1,24)=2.36, p=.138, η2=.09; F(11,264)=1.18, p=.305, η2=.05. The two-way interaction was also not significant, F(11,264)=1.37, p=.190, η2=.05..

Table 1.

Mean reaction time (ms) for 12 Mandarin consonantal contrasts for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in Experiment 1 (with standard deviations in parenthesis)

| Cantonese speakers | Mandarin speakers | |

|---|---|---|

| /ts/-/tʂ/ | 1108 (60) | 1021 (60) |

| /ts′/-/tʂ′/ | 1157 (56) | 1029 (56) |

| /s/-/ʂ/ | 1132 (60) | 1068 (60) |

| /ts/-/tɕ/ | 1080 (59) | 1052 (60) |

| /ts/-/tɕ′/ | 1061 (67) | 991 (67) |

| /ts/-/ɕ/ | 1006 (65) | 968 (65) |

| /ts′/-/tɕ/ | 1086 (71) | 936 (71) |

| /ts′/-/tɕ′/ | 1215 (57) | 945 (57) |

| /ts′/-/ɕ/ | 1029 (59) | 1017 (59) |

| /s/-/tɕ/ | 1055 (62) | 1000 (62) |

| /s/-/tɕ′/ | 1200 (68) | 994 (68) |

| /s/-/ɕ/ | 1050 (74) | 1036 (74) |

Tone discrimination reaction times

Table 2 shows the mean reaction time for each of the tone contrast cases. A 2 (Group: Cantonese vs. Mandarin) × 6 (Tone Type: 6 tonal contrasts) mixed analysis of variance on reaction time for tonal contrasts revealed that the main effect of Group was significant, F(1,24)=4.83, p=.038, η2=.17. The response time of the Cantonese speakers was longer than that of the Mandarin speakers (1261ms vs. 1061ms). The main effect of Tone Type also was significant, F(5,120)=4.36, p<.001, η2=.15; the discrimination time for the T2–T3 contrast was significantly longer than that for the T2–T4 contrast (1277ms vs. 1114ms), p=.001. No interaction between Group and Tone Type was observed, F<1. However, a comparison between the two groups for each tonal contrast revealed that the Cantonese speakers took significantly longer to discriminate the T2-T3 contrast than the Mandarin speakers did, F(1,24)=5.0, p=.035. Recall that this was the same contrast that produced the largest accuracy difference as well.

Table 2.

Mean reaction time (ms) for six Mandarin tonal contrasts for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in Experiment 1 (with standard deviations in parenthesis)

| Cantonese speakers | Mandarin speakers | |

|---|---|---|

| T1–T2 | 1307 (317) | 1096 (210) |

| T1–T3 | 1261 (280) | 1086 (258) |

| T1–T4 | 1231 (340) | 1025 (184) |

| T2–T3* | 1411 (359) | 1143 (243) |

| T2–T4 | 1190 (207) | 1038 (273) |

| T3–T4 | 1232 (257) | 1030 (287) |

p<.05

Discussion

Although individuals who began learning Mandarin at a young age generally showed good performance on consonantal contrasts, these native Cantonese speakers were significantly poorer than the Mandarin speakers at distinguishing six of the tested consonantal contrasts: /ts/-/tʂ/, /ts′/-/tʂ′/, /s/-/ʂ/, /ts′/-/tɕ/, /ts′/-/tɕ′/, and /ts′/-/ɕ/ For two of these contrasts (/ts/-/tʂ/ and /ts′/-/tʂ′/) the difference in performance for the two groups was quite substantial, and the effects primarily affected accuracy.

For the tone contrasts, this pattern reversed -- the accuracy measure did not show robust differences as a function of native language, but there were clear differences in processing speed. The two groups’ A′ scores did not differ significantly in any of the tested tonal contrasts and were all above .90, which means both the Cantonese and the Mandarin speakers can consistently distinguish Mandarin tonal contrasts. However, we found that the Guangzhou Cantonese group took longer to make tone discrimination judgments than the Mandarin group, particularly for the T2–T3 contrast.

Recall that the primary goal of Experiment 1 was to provide an empirical basis for stimulus selection for the following experiments. For the tonal contrast, T2–T3 is the obvious choice. For the consonantal contrast, both /ts/-/tʂ/ and /ts′/-/tʂ′/ are possible choices. We selected the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ case for three reasons: The statistical reliability of this difference was slightly higher than the /ts/-/tʂ/ case, the reaction time difference was higher, and most importantly, the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast offers a better selection of words to be used as stimuli in Experiment 3.

Experiment 2

The discrimination task in Experiment 1 revealed that Guangzhou Cantonese speakers were poorer than Mandarin speakers at discriminating the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ consonantal contrast and the T2–T3 tonal contrast. However, poor performance on an explicit task does not necessarily mean that an ability does not exist. For example, people may show quite good performance on an implicit memory task while completely failing on an explicit task (e.g., Warrington & Weiskrantz, 1968, 1970). Thus, we used the Garner speeded classification paradigm (e.g., Tong, Francis, & Gandour, 2008) to obtain an implicit measure of the listeners’ sensitivity to non-native contrasts. This paradigm includes two tasks: On a baseline task, participants classify stimuli on a target dimension (e.g., consonant) with non-target properties remaining constant on other dimensions (e.g., vowel or tone). On a filtering task, participants make the same judgments, but with variation on the non-target dimension (e.g., changed vowels or tones). Any differences in performance between the baseline and the filter tasks are assumed to be due the listeners’ sensitivity to the variation of the non-target dimension.

Using this methodology, Navarra et al. (2005) asked Spanish-dominant Spanish(L1)-Catalan bilinguals and Catalan-dominant Catalan(L1)-Spanish bilinguals to classify the first syllable of disyllabic words. In the baseline condition, the stimuli consisted of two homogeneous lists (in which all of the words contained only /e/, or only /ε/, in the second syllable). Two orthogonal lists (in which half the words contained /e/ in the second syllable and half contained /ε/ in the second syllable) were used for the filtering task. Although participants were instructed to ignore the second syllable, Catalan-dominant bilinguals responded more slowly in orthogonal lists than in homogeneous lists, indicating that variation of the vowel in the second syllable interfered with processing of the first syllable. In contrast, Spanish-dominant bilinguals did not suffer from this interference. These results suggest that only Catalan-dominant bilinguals were sensitive to the difference between /e/-/ε/, with the difference influencing their decisions on supposedly irrelevant syllables. Here we use a similar method to compare the differences between Guangzhou Cantonese native speakers and Mandarin native speakers in processing Mandarin /ts′/-/tʂ′/ and T2–T3 contrasts. We test whether task-irrelevant variation of either consonantal or tonal properties will affect classification performance, with any such effect indicating perceptual sensitivity to the varied information.

Method

Participants

Fourteen native Guangzhou Cantonese speakers (mean age of 22 years, ranging from 18 to 25 years) and 14 native Mandarin speakers (mean age of 21 years, ranging from 18 to 25 years) participated in Experiment 2. All of the participants were selected from the same two populations as in the first experiment, but none of them had participated in the previous study. The Guangzhou Cantonese native speakers had been using Mandarin Chinese for an average of 16 years, ranging from 11 to 20 years. No participant reported any hearing problem, and all received small gifts for their participation.

Stimuli

All stimuli were recorded by a native Mandarin speaker. For consonant processing, ten different instances of /ts′Ɑ(1)/, ten instances of /tʂ′Ɑ(1)/, ten instances of /ts′ (1)/ and ten instances of /tʂ′ (1)/ were recorded by the speaker. The stimuli were used to construct two homogeneous lists and two orthogonal lists. Each homogeneous list consisted of 20 instances which contained the same consonant [List 1: 10 instances of /ts′▪ (1)/ and 10 instances of /ts′Ɑ(1)/; List 2: 10 instances of /tʂ′ (1)/ and 10 instances of /tʂ′(1)/]. Each orthogonal list consisted of five different instances of each word [five instances of /ts′ (1)/, five instances of /tʂ′ (1)/, five instances of /ts′Ɑ(1)/ and five instances of /tʂ′Ɑ(1)/; the two lists only differed in the particular tokens assigned to each list].

For tone perception, ten different instances of /pi(2)/, /pi(3)/, /pⱭ(2)/, and /pⱭ(3)/ were recorded by the same speaker. Four lists were created as follows: Each homogeneous list consisted of 20 instances which contained the same tone [List 1: 10 instances of /pi(2)/ and 10 instances of /pⱭ(2)/; List 2: 10 instances of /pi(3)/ and 10 instances of /pⱭ(3)/]. Each orthogonal list consisted of five different instances of each word [five instances of /pi(2)/, five instances of /pi(3)/, five instances of /pⱭ(2)/ and five instances of /pⱭ(3)/; the two lists only differed in the particular tokens assigned to each list]. All stimuli were digitized (44.1kHz) and edited with GoldWave 5.22 sound editing software.

Procedure

Participants were tested in the same lab, with the same equipment, as in Experiment 1. The experiment consisted of two blocks, one for consonant processing and the other for tone processing. Each block contained two homogeneous lists and two orthogonal lists. Each list included 20 tokens (consonants or tones) and every token in each list was repeated twice. Thus, the participants received 160 words in each block (4 lists × 20 tokens × 2 repetitions).

The participants were instructed to indicate whether the vowel of each word was /Ɑ/ or /▪/ by pressing two corresponding keys. They were given written instructions and the two critical phonemes were specified in Pinyin (a and i), which is the official system to transcribe Chinese characters into the Roman alphabet in China. They were told to ignore the consonants and tones, and to make their decisions as quickly and accurately as possible. Each trial began 750ms after the participant had responded. If a participant failed to respond within 3000ms, a new trial would be presented.

The experiment was preceded by a practice. Eight practice trials were included, and all of the critical contrasts in the experiment were tested in the practice. No feedback was given to the participants. The order of the two blocks and the four lists was counter-balanced across participants. The order of tokens within each list was random.

Results and Discussion

Reaction times were measured from the onset of each word. Reaction times lower than 200 ms or greater than three standard deviations from the mean were discarded (1.0% of all responses).

/ts′/-/tʂ′/ analysis

The overall accuracy rate of vowel identification was quite high, .97 for Guangzhou Cantonese speakers and .99 for Mandarin speakers. Thus, we focus on the reaction times. The average reaction time for each type of list was calculated for the two groups of participants (Cantonese vs. Mandarin) separately. Figure 3 shows the average reaction times for the consonant contrast. We conducted a 2 (Group: Guangzhou Cantonese vs. Mandarin) ×2 (List: homogeneous vs. orthogonal) mixed analysis of variance on the reaction times for the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast. The main effect of Group was not significant, F<1. The main effect of List was significant, F(1,26)=32.22, p<.001, η2=.55, reflecting the faster reaction times for homogeneous lists than for orthogonal lists (574ms vs. 629ms). Critically, we observed a significant interaction between Group and List, F(1,26)=16.85, p<.001, η2=.39.

Figure 3.

Mean reaction times (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for /ts′/ words and /tʂ′/ words by the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in homogeneous lists and orthogonal lists in Experiment 2.

In order to clarify the nature of the critical interaction, we analyzed the simple effect of List for each group. The simple effect of List for the Cantonese speakers was not significant, F(1,26)=1.24, p=.277. In contrast, there was a robust effect for the Mandarin speakers, F(1,26)=47.83, p<.001, with slower responses in orthogonal lists than homogeneous lists (665ms vs. 569ms). This pattern clearly shows that Mandarin speakers suffered interference from the consonantal variation, while the Cantonese speakers did not.

T2–T3 analysis

Again, the overall accuracy rate of vowel identification was quite high, .97 for Guangzhou Cantonese speakers and .98 for Mandarin speakers. Thus, as with the consonants, we focus on the reaction times. Figure 4 shows the means for the two groups in the two conditions. A 2 (Group: Guangzhou Cantonese vs. Mandarin) × 2 (List: homogeneous vs. orthogonal) mixed analysis of variance on reaction times showed that there was no main effect of Group, F<1. The main effect of List was significant, F(1,26)=67.10, p<.001, η2=.72, due to faster reaction times for homogeneous lists than for orthogonal lists (469ms vs. 504ms). For our central theoretical question, the critical result is the interaction between Group and List, and this was significant, F(1,26)=5.33, p=.029, η2=.17.

Figure 4.

Mean reaction times (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for T2 words and T3 words by the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers in homogeneous lists and orthogonal lists in Experiment 2.

Simple effect analysis revealed that both the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F(1,26)=17.30, p<.001] and the Mandarin speakers [F (1,26)=55.13, p<.001] took longer to respond in orthogonal lists than in homogeneous lists .This indicates that both Cantonese and Mandarin speakers suffered interference from the tonal variation when judging the vowels, but the Mandarin speakers (472ms vs. 517ms) were more affected than the Cantonese speakers were (466ms vs. 490ms).

Discussion

Experiment 2 investigated the perception of non-native consonantal and tonal contrasts using an implicit method, and the results nicely complement those obtained in the explicit discrimination task of Experiment 1. When the Mandarin /ts′/-/tʂ′/ consonant contrast varied in a task-irrelevant way, Cantonese speakers were unaffected, whereas the Mandarin speakers were significantly slower than when the consonant was kept constant. The fact that the Cantonese speakers were not influenced by the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ variation suggests that they are not sensitive to the difference between Mandarin /ts′/ and /tʂ′/. In Experiment 1, this contrast was difficult for them to discriminate, and the reasonably good accuracy that they showed there may have been based on attending to subtle (acoustic) differences that are not usable outside of the simple comparison situation of an explicit discrimination task.

As in Experiment 1, the difference between the two groups was smaller for the tonal contrast than for the consonantal contrast. Both the Guangzhou Cantonese and the Mandarin speakers were slower on the orthogonal lists than on the homogeneous lists. Still, the expected difference was found: Variation of tone was more disruptive for the Mandarin subjects than for the native Cantonese speakers.

Both the explicit task in Experiment 1 and the implicit task in Experiment 2 provide evidence that Guangzhou Cantonese speakers cannot easily distinguish the Mandarin consonant /ts′/ from the Mandarin consonant /tʂ′/; both experiments suggest somewhat better but still relatively poor abilities to perceive the Mandarin T2–T3 contrast. Experiment 3 was designed to investigate how the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers lexically represent minimal pairs of words differing only in each of these contrasts.

Experiment 3

The first two experiments focused on the perceptual processing of Mandarin consonantal and tonal contrasts by native Cantonese speakers who had learned Mandarin at an early age. Experiment 3 is designed to examine the lexical representation of these phonological contrasts. Specifically, we wish to determine whether minimal pairs of words containing consonants or tones that are very poorly discriminated by the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers are stored as homophones in their lexical representations.

We use a medium-term auditory repetition priming paradigm (Dufour et al., 2007; Pallier et al., 2001; also see Sumner & Samuel, 2009) to address this question. In this paradigm, participants make lexical decision judgments on a series of words and non-words. Critically, in some cases a word is later followed by either a true repetition, or by an item that only differs by one critical feature. The medium-term repetition priming effect is defined as a reaction time decrease between the first and second occurrences of a repeated item. For the current purposes, this definition also includes the occurrence of an item and its counterpart in a minimal pair. Pallier et al. and Dufour et al. both found a significant priming effect in the minimal pair condition when the difference between the two items was a non-native segmental distinction (and, Pallier et al. showed that this effect only occurred for words, indicating that the task taps lexical effects). Based on this effect, these authors concluded that minimal pairs of words were stored as homophones in the lexical representations of non-native participants.

In contrast, as discussed in the Introduction, researchers using the eye-tracking methodology (Cutler & Weber, 2004; Cutler, Weber, Otake, 2006; Escudero, Hayes-Harb, Mitterer, 2008) have concluded that in these cases lexical representations include different representations for the two sounds. This conflicting conclusion is based on the presence of asymmetric competition effects: Words with native sounds compete with those having non-native segments more than vice versa. In the Pallier et al. (2001) and Dufour et al. (2007) priming studies, the researchers did not analyze the two opposite priming directions in the minimal pair conditions separately. As such, whether the two members of a minimal pair produce symmetric priming remains uncertain.

Sumner and Samuel (2009) tested speakers of the New York City/Long Island dialect of American English to determine whether their lexical representations included dialectal variants or the forms found in General American English. Using a priming methodology similar to that of Pallier et al. (2001) and Dufour et al. (2007), they found symmetric priming for individuals who overtly produced the local dialect, but found asymmetric priming for individuals in the same linguistic community whose speech did not include the local phonetic variation. These results indicate that the priming technique can reveal differences in the details of lexical representations. Thus, in Experiment 3 we tested and analyzed both orders of presenting the two members of a minimal pair, to see whether there would be an asymmetric pattern of priming. As research using the eye-tracking approach has shown, asymmetries indicate that two forms are not homophonous.

The critical contrasts in Experiment 3 were those that we have shown to be relatively difficult for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers to discern: /ts′/-/tʂ′/ and T2–T3. The results of Experiments 1 and 2 indicate that the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast is extremely difficult for the Cantonese speakers, and the T2–T3 contrast is moderately difficult. For comparison purposes, we also tested a consonantal contrast that exists in both Cantonese and Mandarin (/t/-/t′/) and a tonal contrast (T2–T4) that was easily distinguished by both groups in Experiment 1. Both groups of participants should be able to distinguish these phonetic and prosodic contrasts easily, providing a baseline with which we can interpret the two critical cases.

Method

Participants

Thirty-six native Guangzhou Cantonese speakers (mean age of 22 years, ranging from 16 to 29 years) and 36 native Mandarin speakers (mean age of 23 years, ranging from 18 to 26 years) participated in Experiment 3. All were tested in the same lab, with the same equipment, as in the previous experiments. Six Cantonese speakers and four Mandarin speakers had participated in Experiment 1; none had participated in Experiment 2. Participants were recruited in the same way as in the previous experiments. The Guangzhou Cantonese native speakers had been using Mandarin Chinese for an average of 15 years, ranging from 8 to 22 years. No participants reported any hearing problem, and all received small gifts for their participation.

Stimuli

Twenty minimal pairs of disyllabic words based on each difficult contrast (/ts′/-/tʂ′/ and T2–T3), and 20 minimal pairs of words based on each control contrast (/t/-/t′/ and T2–T4) were initially selected as possible experimental stimuli. For example, the words /ts′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ (2)/ [“

”, meaning temple] and /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′ɕŋ(2)/ [“

”, meaning temple] and /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′ɕŋ(2)/ [“

”, meaning pond] comprise a minimal pair that differs only in the critical consonantal contrast. There was no semantic relationship between the two members in any pair of words. To make sure that participants would accept the experimental stimuli as real words, 22 students who did not take part in the present experiment were asked to make lexical decisions on the 80 words. Only words that were rated as real words by more than 80% of the students were kept. Based on this pilot testing, 16 pairs of words for each contrast were selected as critical stimuli; the tested consonants and tones were present in either the first or second syllable in approximately equal frequency. The median frequencies for the /ts′ɨ/ and /tʂ′ɨ/ words were 195 and 210, respectively. The median frequencies for the /t/ and /t′/ words were 400 and 327, respectively. The median frequencies for the T2 and T3 words were 596 and 552, respectively. The median frequencies for the T2 and T4 words were 511 and 407, respectively (per million, retrieved from CCL corpus: http://ccl.pku.edu.cn:8080/ccl_corpus/index.jsp?dir=xiandai). Appendix D presents the critical stimuli used in Experiment 3.

”, meaning pond] comprise a minimal pair that differs only in the critical consonantal contrast. There was no semantic relationship between the two members in any pair of words. To make sure that participants would accept the experimental stimuli as real words, 22 students who did not take part in the present experiment were asked to make lexical decisions on the 80 words. Only words that were rated as real words by more than 80% of the students were kept. Based on this pilot testing, 16 pairs of words for each contrast were selected as critical stimuli; the tested consonants and tones were present in either the first or second syllable in approximately equal frequency. The median frequencies for the /ts′ɨ/ and /tʂ′ɨ/ words were 195 and 210, respectively. The median frequencies for the /t/ and /t′/ words were 400 and 327, respectively. The median frequencies for the T2 and T3 words were 596 and 552, respectively. The median frequencies for the T2 and T4 words were 511 and 407, respectively (per million, retrieved from CCL corpus: http://ccl.pku.edu.cn:8080/ccl_corpus/index.jsp?dir=xiandai). Appendix D presents the critical stimuli used in Experiment 3.

For the lexical decision task, 64 minimal pairs of nonwords were created in the same way as the critical stimuli, 16 for each contrast. An additional 64 words and 64 nonwords were used as fillers. No critical consonants were included in the fillers. Since there are only four tones in Mandarin and three were tested in the critical stimuli, all Mandarin tones were used in the fillers.

All stimuli were recorded by a native Mandarin speaker. All items were digitized (44.1kHz) and edited with GoldWave 5.22 sound editing software.

Procedure

The participants were tested individually in a sound-attenuated booth. The stimuli were presented via headphones at a comfortable listening level. Four counterbalanced lists of the 384 items ([16 pairs of words × four contrasts] +[16 pairs of nonwords × four contrasts] + 64 filler words + 64 filler nonwords) were created and each participant was assigned to one list. In each list, one member of the minimal pair was followed, 8 to 20 items further down in the list, either by itself or by the other member in the pair. The members of a given minimal pair appeared in the same positions in the four lists, but were counterbalanced across the lists. The participants were required to make a lexical decision for each item by pressing corresponding keys. They were told to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. The following trial began 750ms after the participant had responded. If a participant failed to respond within 3500ms, a new trial would be presented. The experiment was preceded by a practice. Five words and five non-words that were not tested in the experiment were used, with no feedback given to the participants.

Each participant was tested in four prime conditions. An example of the four conditions for the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast is provided in Table 3. As the table shows, the four prime conditions represent the crossing of /ts′/ and /tʂ′/ as the first member of a pair with /ts′/ and /tʂ′/ as the second member of the pair.

Table 3.

Examples of the four conditions for the /ts′/-/t ʂ′/contrast

| Prime condition | First occurrence | Second occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| /ts′/-/ts′/ | /ts′ɨ (2)t′ Ɑŋ (2)/ | /ts′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ |

| /tʂ′/-/tʂ′/ | /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′ Ɑŋ(2)/ | /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ |

| /ts′/-/tʂ′/ | /ts ′ (2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ | /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ |

| /tʂ′/-/ts′/ | /tʂ′ ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ | /ts′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/ |

Here, /ts′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/[“

”] means temple and /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/[“

”] means temple and /tʂ′ɨ(2)t′Ɑŋ(2)/[“

”] means pond.

”] means pond.

Results and Discussion

Responses to fillers were not included in the analyses. The data of four participants (two Mandarin speakers and two Guangzhou Cantonese speakers) were excluded because of very high error rates (more than 25%). The average error rate for the remaining 68 participants was less than 9%. Reaction times lower than 200 ms or greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean were discarded (3.0% of all responses). The present experiment was a 2 (Group: Mandarin vs. Cantonese) × 4 (Prime Condition: 2 identity conditions vs. 2 minimal pair conditions) × 2 (Occurrence: first vs. second) mixed design. For each contrast, the difference between the first and second occurrence (the priming effect) was assessed within four prime conditions for each group. Accuracy was consistently very high. In all cases no significant accuracy effects were observed for either words or nonwords, and no significant reaction time effects were observed for nonwords. Thus, we focus here on the reaction times for the critical words, as is typically the case in lexical decision studies. F values are reported by participants (F1) and by items (F2). We report analyses of the priming effects here; in Appendix E, we report analyses of the overall reaction times.

Consonant contrasts: /ts′/-/tʂ′/ analysis

Priming effects in each condition are shown in Figure 5. We first consider identity priming -- cases in which the same token occurred twice. Previous studies using medium- and long-term priming indicate that such repetition should lead to faster responses for the second occurrence. As the left side of Figure 5 shows, such repetition priming was robust. A strong priming effect was observed when /ts′/ words were repeated (/ts′/-/ts′/ condition) for both the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=11.46, p=.001; F2(1,30)=5.39, p=.027] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=10.75, p=.002; F2(1,30)=7.64, p=.010]. There was also a priming effect when /tʂ′/ words were repeated (/tʂ′/-/tʂ′/ condition) for both the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=5.21, p=.026; F2(1,30)=14.53, p=.001] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=4.93, p=.030; F2(1,30)=3.49, p=.071].

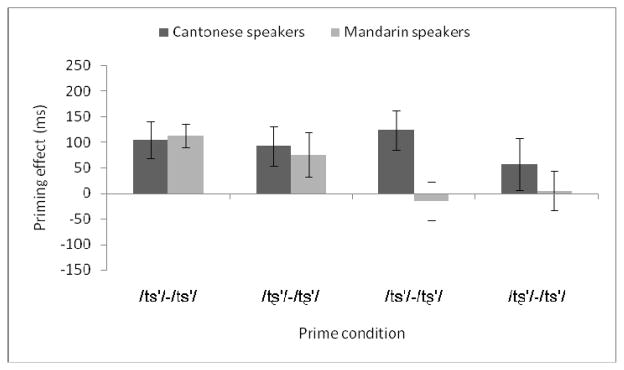

Figure 5.

Priming effects (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers across the four prime conditions for the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast in Experiment 3.

Having established that our testing conditions are sensitive to item repetition, we can see whether minimal pairs were treated as cases of repetition. For the Mandarin speakers, there should not be repetition priming because the first and second members in a pair are different lexical items in Mandarin. The results are consistent with this expectation: No priming effect was found for the minimal pairs when /tʂ′/ words preceded their /ts′/ counterparts for the Mandarin speakers [F1<1; F2<1]; the same null effect obtained when a /ts′/ word preceded its /tʂ′/ minimal pair [F1<1; F2(1,30)=1.87, p=.181].

As Figure 5 shows, the results for the native Cantonese speakers were quite different. There was a very large priming effect when /tʂ′/ words preceded their /ts′/ counterparts [F1(1,66)=9.94, p=.002; F2(1,30)=5.703, p=.023]. This large priming effect indicates that for the Cantonese listeners, the minimal pairs were not distinct. However, if the pairs were stored as homophones (as the large /tʂ′/-/ts′/ priming effect might suggest), then we should see a similarly large priming effect when /ts′/ words preceded their /t ′/ minimal pairs, and the results are not consistent with this symmetric hypothesis: There was a priming effect of approximately 60 ms, but this trend did not approach significance [F1(1,66)=1.63, p=.21; F2<1]. Thus, numerically there is a clear asymmetry. However, the 60 ms trend requires caution in our interpretation.

Given the importance of this comparison for our inferences regarding lexical representation of this difficult non-native contrast, and the indeterminate result, we brought in a new group of 24 native Guangzhou participants and had them do the same task as the original group. These participants were drawn from the same population, and were tested on the same equipment in the same lab. Two of these new participants exceeded our cutoff of 25% errors, leaving 22 usable data sets.

The new group showed no hint of priming in the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ condition, actually producing a 13 ms reversal of the priming pattern. We conducted an ANOVA of the priming effects in the four conditions, with Replication (the original group of Cantonese participants vs. the new group of Cantonese participants) as a factor. Figure 6 presents the average priming effects for the four conditions, combining the results of the original and the new Cantonese group. Again, the two identity priming conditions exhibited large priming effects (for the /ts′/-/ts′/ condition, F1(1, 55)=14.13, p<.001; F2(1, 31)=8.91, p=.005; for the /tʂ′/-/tʂ′/ condition, F1 (1, 55)=19.81, p<.001); F2(1, 31)=53.81, p<.001. As the figure makes clear, the /tʂ′/-/ts′/ condition also produced a large priming effect, F1 (1,55) = 11.81, p=.001; F2 (1,31)=2.81, p=.10. This priming effect was indistinguishable from both the /ts′/-/ts′/ identity condition (F1<1; F2<1) and the /tʂ′/-/tʂ′/ identity condition (F1<1; F2<1). In contrast, the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ condition produced a negligible effect (F1<1, F2<1), which was reliably different from the average priming effect of the other three conditions, F1 (1,54) = 5.20, p=.027, F2(1, 30)=6.30, p=.018.

Figure 6.

Priming effects (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the Cantonese speakers (collapsed across the two testing groups) across the four prime conditions for the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast in Experiment 3.

Thus, using the larger sample, we see clear evidence for asymmetric priming effects, a pattern that is inconsistent with the members of the minimal pairs being stored as homophones. Just as the results of eye-tracking studies have suggested (Cutler & Weber, 2004; Cutler, Weber, Otake, 2006; Escudero, Hayes-Harb, Mitterer, 2008), contrasts that are very difficult to distinguish at the phonetic level are nonetheless represented differentially at the lexical level.

Consonant contrasts: /t/-/t′/ analysis

Priming effects in each condition for these consonantal controls are shown in Figure 7. Priming effects were found in the two identity priming conditions for both groups. In the /t/-/t/ condition, the priming effect was significant for both the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=9.02, p=.004; F2(1,30)=16.47, p<.001] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=12.48, p=.001; F2(1,30)=13.93, p=.001]. In the /t′//t′/ condition, the priming effect was also robust for both the Guangzhou Cantonese group [F1(1,66)=19.69, p<.001; F2(1,30)=18.14, p<.001] and the Mandarin group [F1(1,66)=5.86, p=.018; F2(1,30)=4.71, p=.038].

Figure 7.

Priming effects (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers across the four prime conditions for the /t/-/t′/ contrast in Experiment 3.

As the /t/-/t′/ pairs are clearly different words, with no phonetic ambiguity even for the Cantonese speakers, there should not be any priming for these minimal pairs. This expectation was confirmed: No priming effect was found in either the /t/-/t′/ condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1(1,66)=1.66, p=.202; F2(1,30)=1.16, p=.291; for the Mandarin speakers: F1(1,66)=3.15, p=.081, F2<1] or in the /t′/-/t/ condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1(1,66)=2.44, p=.123; F2<1; for the Mandarin speakers: F1<1, F2<1].

Tonal contrasts: T2–T3 analysis

Priming effects in each condition are shown in Figure 8. As expected, priming effects were found in the two identity priming conditions for both groups. In the T2-T2 condition, the priming effect was significant for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=4.96, p=.029; F2(1,30)=29.52, p<.001] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=10.28, p=.002; F2(1,30)=5.26, p=.029]. The same was true in the T3-T3 condition, with a priming effect for both the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=22.82, p<.001; F2(1,30)=8.52, p=.007] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=10.98, p=.001; F2(1,30)=13.63, p=.001].

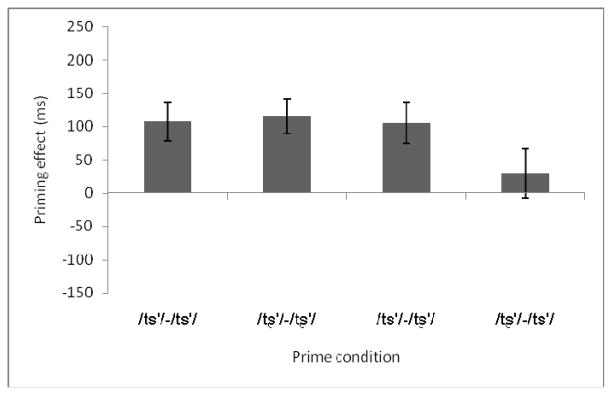

Figure 8.

Priming effects (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers across the four prime conditions for the T2–T3 contrast in Experiment 3.

We saw that with the consonantal minimal pairs there were different results for the native Mandarin speakers (no priming) and the Cantonese speakers (priming, in one direction). The tonal manipulation produced different results: No priming effect was found in either the T2–T3 condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1<1, F2<1; for the Mandarin speakers: F1(1,66)=1.54, p=.219; F2(1,30)=1.35, p=.225] or in the T3-T2 condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1<1, F2<1; for the Mandarin speakers: F1<1, F2<1]. The results for the Mandarin speakers mirror those for the consonantal case, and reflect the different lexical status of the members of each word pair. It is interesting that the same non-priming result is found for the Cantonese speakers. This pattern is consistent with the results of the first two experiments, which suggested better discrimination of the tonal contrast than the consonantal one.

Tonal contrasts: T2–T4 analysis

Priming effects in each condition for the tonal controls are shown in Figure 9. Priming effects were found in the two identity priming conditions for both groups. In the T2-T2 condition, the priming effect was significant for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=11.33, p=.001; F2(1,30)=6.05, p=.001] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=5.96, p=.017; F2(1,30)=9.58, p=.002]. In the T4-T4 condition, a priming effect was obtained for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers [F1(1,66)=6.97, p=.010; F2(1,30)=7.457, p=.020] and the Mandarin speakers [F1(1,66)=4.05, p=.048; F2(1,30)=5.25, p=.029]. As we would expect, given the clear discriminability of T2 and T4 for both groups, no priming effect was found in either the T2–T4 condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1(1,66)=1.90, p=.173; F2(1,30)=2.75, p=.108; for the Mandarin speakers: F1<1, F2<1], or in the T4-T2 condition [for the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers: F1(1,66)=1.06, p=.307; F2(1,30)=3.40, p=.075; for the Mandarin speakers: F1<1, F2<1].

Figure 9.

Priming effects (with error bars representing the standard error of the mean) for the Cantonese speakers and Mandarin speakers across the four prime conditions for the T2–T4 contrast in Experiment 3.

Discussion

The priming effects varied in systematic ways between the two groups of speakers and among the different minimal contrasts. Both the Cantonese and the Mandarin speakers exhibited strong and consistent repetition priming when the same word was repeated. In contrast, the effects were diverse in the minimal pair conditions across different types of contrasts. As expected, the Mandarin speakers showed no repetition priming for an item and its counterpart in a minimal pair, for all contrasts that were tested. This result confirms that Mandarin speakers were capable of distinguishing these contrasts -- the minimal pairs differing in a consonant or tone were different words for them, and hence there was no lexically-mediated medium term priming.

The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers produced a rich pattern of priming effects for the minimal pairs, providing insight into the lexical representations for a siblang learned at an early age. The /t/-/t′/ control condition confirmed that Mandarin minimal pairs that are based on a good phonetic contrast for the Cantonese subjects produce no priming. Thus, any priming effects reflect shared lexical representations between the first and second members of a pair. In this context, the robust priming effect in the minimal pair condition for the /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast indicates that this contrast is not maintained in the lexicon for these early non-native Mandarin learners. However, the lack of priming for the /tʂ′/-/ts′/case shows that these minimal pairs are not homophones – if they were, we would have found robust priming for such “repetition”, and we did not. This pattern of asymmetric priming is reminiscent of the asymmetric eyetracking patterns reported by Cutler et al. (2006) and Weber and Cutler (2004). Recall that those authors suggested that such an asymmetry implies that only one member of the pair appears in the lexical representations, one that is closer to the subject’s native language phoneme (in this case, /ts′/). In the General Discussion, we will consider how the different processing requirements for the eyetracking and priming paradigms constrain the theoretical implications for lexical representation and processing.

The results for the tonal conditions were extremely clear. When the tones were kept constant in a pair, robust repetition priming was consistently observed. When tone was varied between the first and second member of a minimal pair (keeping the segmental information constant), neither the Guangzhou Cantonese nor the Mandarin speakers exhibited repetition priming. This was true for the critical T2–T3 case and for the T2–T4 control contrasts. These results indicate that words differing in tones are represented as different lexical items for both Guangzhou Cantonese and Mandarin speakers.

General Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate how consonantal and tonal contrasts are perceived and represented by experienced non-native speakers who learn a siblang at an early age. Guangzhou Cantonese and Mandarin participants were tested in three experiments. We first used an explicit discrimination methodology to provide a strong empirical basis for stimulus selection for the subsequent experiments. We then combined the Garner methodology with the medium term priming paradigm to explore the phonetic and lexical processing of non-native contrasts. We believe that this kind of interlocking approach provides a richer picture of non-native language processing than earlier studies have provided.

Comparison of non-native segmental and prosodic processing

The results of Experiment 1 revealed that the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers had difficulty distinguishing specific Mandarin consonantal contrasts, particularly the /ts/-/tʂ/ and /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrasts. These results are consistent with the results for another pair of siblangs, Catalan and Spanish (Pallier et al,, 1997; Pallier et al., 2001; Sebastián-Gallés & Soto-Faraco, 1999; Sebastián-Gallés et al., 2005; Sebastián-Gallés et al., 2006): Non-native speakers are poor at distinguishing certain segmental contrasts despite their otherwise high proficiency. The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers who participated in our research have a good command of Mandarin Chinese. They started learning it at an early age -- six or seven -- which is within the age range usually assumed to allow mastering a second language. Nonetheless, their perception of certain Mandarin consonantal contrasts was significantly worse than their native counterparts. These explicit discrimination difficulties were reflected in both the implicit perceptual measure of phonological processing in Experiment 2 and the lexical priming effects in Experiment 3.

Because the same individuals were tested on both segmental and tonal contrasts, the present research provides the first direct comparison of dialect effects for tonal versus segmental contrasts. The three experiments were designed to provide this comparison at increasingly abstract levels of processing: The discrimination test in Experiment 1 can be done on an acoustic basis, the Garner interference of Experiment 2 can be generated at a phonological (or for tones, suprasegmental) level, and the priming effects in Experiment 3 are lexically driven (Pallier et al., 2001).

Generally speaking, the results for the tonal contrasts in the three experiments could be characterized as an attenuated version of what was found for the consonantal cases, but with important variation as a function of the tested level. On the explicit discrimination test, the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers demonstrated better tone perception than segment perception; in both cases their perceptual ability was worse than that of the native Mandarin speakers, but the difference was smaller for tones than segments. The pattern of Garner interference also showed stronger differences for segmental contrasts than for tonal, in an interesting way. Unlike the native Mandarin speakers, the non-native speakers suffered no interference from variation of /ts′/-/tʂ′/, indicating that during perception they are not sensitive to this phonological contrast. When the variation was based on tone, both native and non-native speakers were impaired by the variation, with native speakers showing significantly more interference than the non-native ones. At the lexical level, we again saw evidence that non-native speakers do not represent the segmental contrast well, leading to significant priming from words (the /tʂ′/-/ts′/ case) that did not produce such priming for the native speakers. Again, for the non-native speakers the tonal contrast was better represented than the segmental one, with the two groups of speakers showing similar patterns of lexical activation for words differing in tones.

The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers might be better at processing Mandarin tones than consonants because of particular aspects of their language experience with Mandarin Chinese. This suggestion is grounded in research indicating that non-native tones seem to be easier to learn than non-native segments. English speakers’ identification accuracies of Mandarin tones increased from 69% to 90% after several weeks of training (Wang, Spence, Jongman & Sereno, 1999), and identification of non-native tones increased from a baseline of 50–59% to at least 81–88% after intensive training of only a matter of hours (So, 2006a). With certain training methods, performance was as high as 91%–97% (So, 2006a). Importantly, these learning effects were found to be long lasting.

These large training effects for tones contrast with the much smaller changes observed in attempts to improve segment perception. As we have discussed, for contrasts such as English /ɹ/-/l/, the effect of training can be impressively weak. Three weeks of training for Japanese speakers trying to identify English /ɹ/ and /l/ only yielded an increase from 78% to 86% (Logan et al., 1991). Other training studies also found only a 12% (Lively et al., 1994) or a 16% (Bradlow et al., 1997) improvement in non-native consonant learning. The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers in the current study received comprehensive education in Mandarin Chinese beginning at an early age. Given the tone training results, we would expect them to be able to process Mandarin tones relatively well, and the results are consistent with this.

In this context, it is worth noting that our Cantonese listeners showed little of the perceptual difficulties experienced by the Cantonese participants in So’s studies (2005a; 2005b; 2006a; 2006b). A critical difference is that So tested Hong Kong Cantonese speakers, whereas our listeners were Guangzhou Cantonese speakers. There are some differences between the Hong Kong Cantonese and Guangzhou Cantonese tone systems, but more importantly, there are differences between the language experiences of the two populations. The Hong Kong Cantonese speakers who participated in So’s studies were naïve listeners of Mandarin Chinese — Hong Kong speakers do not have much education or training in Mandarin. In contrast, our participants were quite proficient in Mandarin, despite its being non-native.

We noted in the Introduction that Best et al.’s PAM model has the potential to be applied to the case we are studying. Overall, the model does seem to be able to offer at least a qualitative account of how our Cantonese listeners perceived the non-native Mandarin contrasts. Cantonese does not have the consonants /tʂ/, /tʂ′/, /ʂ/, /tɕ/, /tɕ′/ and/ɕ/, and although /ts/, /ts′/ and /s/ exist in both Mandarin and Cantonese, they are pronounced somewhat differently in the two siblangs (Bauer & Benedict, 1997). In Experiment 1 the Guangzhou Cantonese speakers were significantly worse than native Mandarin speakers at discerning the /ts/-/tʂ/, /ts′/-/tʂ′/, /s/-/ʂ/, /ts′/-/tɕ/, /ts′/-/tɕ′/, and /ts′/-/ ɕ/ contrasts. They may have assimilated Mandarin /ts/and /tʂ / to Cantonese /ts/, Mandarin /ts′/ and /tʂ′/ to Cantonese /ts′/, and Mandarin /s/ and /ʂ/ to Cantonese /s/. However, the two members of each contrast would likely differ in their goodness of fit to the Cantonese consonants. Mandarin /ts/, /ts′/, and /s/ should be relatively good exemplars of the Cantonese categories, while Mandarin /tʂ/, /tʂ′/ and /ʂ/ should be poorer exemplars. Similarly, Mandarin /tɕ/, /tɕ′/ and /ɕ/ could be assimilated to Cantonese /ts′/, but they are all poor instances of this category. PAM would predict that single category assimilation contrasts would be relatively difficult for the Cantonese speakers to perceive. In contrast, the Cantonese speakers were relatively good at discriminating the other six Mandarin consonantal contrasts in Experiment 1 (/ts/-/tʂ/, /ts′/-/tʂ′/, /s/-/ /, /ts′/-/tɕ/, /ts′/-/tɕ′/, and /ts′/-/ ɕ/). One reason may be that although we used the same syllable-final vowel (i.e., i) with all of the consonants, this vowel sounds slightly different when following /ts/, /ts′/, and /s/ versus /tɕ/, /tɕ′/, and /ɕ/, with the former more like [▪] and the latter more like [i]. This difference might have helped participants distinguish the contrasts, but it is interesting to note that the discrimination between /ts′/ and /tɕ/, /tɕ′/, /ɕ/ was rather poor. PAM provides a better prediction for this result. It is plausible that Mandarin /tɕ/, /tɕ′/ and /ɕ/ would all be assimilated to Cantonese /ts′/ while Mandarin /ts/ and /s/ are assimilated to Cantonese /ts/ and /s/, respectively. According to PAM, if the two members of a contrast can be assimilated to different native categories, they should be well discriminated, consistent with our findings.

PAM can also provide a reasonable explanation for our tone results. The Guangzhou Cantonese speakers experienced less difficulty in discriminating Mandarin tonal contrasts than segmental ones. The largest effect of non-native experience was that the Cantonese speakers took longer to discriminate Mandarin Tones 2 and 3 than the native Mandarin subjects. Thus, the native dialect had some effect, but the constraint is much smaller than that for the consonant system. Guangzhou Cantonese has a similar tone (35) to that of Mandarin Tone 2 (35), but not to Mandarin Tone 3 (214). Therefore, while Mandarin Tone 2 could have been assimilated to Cantonese 35, the situation for Tone 3 is more difficult. So (2006b) has suggested that Mandarin Tone 3 (214) might also be assimilated to Cantonese 35, or to Cantonese 23; others have suggested it might be more similar to Cantonese 33 (Francis et al., 2008). Given this unsettled analysis, in PAM’s taxonomy of possible relationships of the two members of a contrast, Mandarin Tones 2 and 3 might best be considered a “Categorized (Tone 2) – Uncategorized (Tone 3)” contrast because Tone 3 could be assimilated to more than one Cantonese tone category. PAM predicts that contrasts of this type should be distinguished moderately well, which is what we observed.

It is also possible that Cantonese speakers have difficulty distinguishing this tonal contrast because they are more sensitive to the average height of the pitch of a tone than the direction of the pitch, while Mandarin speakers weigh direction more than height (Francis, et al., 2008; Gandour, 1983; Gandour & Harshman, 1978; Guion & Pederson, 2007). Since Mandarin Tone 2 (35) and Tone 3 (214) start and end with similar f0 heights, but differ in the direction of f0 change, it is reasonable to expect that Cantonese speakers will find this contrast difficult.

The lexical representation of non-native contrasts

There is a small existing literature that has examined how non-native contrasts are stored in the lexicon. Experiment 3 was designed to provide new evidence to address this issue, using medium term repetition priming. The task’s sensitivity was confirmed by the robust identity priming effects in every condition, for both native and non-native listeners. In contrast, when a lexical tone was varied between the first and second member of a minimal pair, neither the Guangzhou Cantonese nor the Mandarin speakers displayed a priming effect. These results indicate that words differing in tones are represented as different lexical items for both early learners and native speakers. Given that training studies show relatively good learning of tones compared to learning of non-native segmental contrasts, it makes sense that native Cantonese speakers who have had early and extensive experience with Mandarin would show evidence of incorporating the proper tones in their lexical representations.

For the segmental /ts′/-/tʂ′/ contrast, the native Mandarin speakers produced a pattern of priming that is exactly as one would expect: Because two tokens that differ in this segmental contrast are different Mandarin words, prior presentation of one does not prime later presentation of the other. The question posed in Experiment 3 was whether Guangzhou Cantonese speakers would show priming effects for these minimal pairs, given that Experiments 1 and 2 showed /ts′/-/tʂ′/ to be perceptually almost indistinguishable for them. Previous priming studies of the Catalan-Spanish siblangs (Pallier et al., 2001) and of two dialects of French (Dufour et al., 2007) found such priming for minimal pairs. Here, when the member of the minimal pair with /tʂ′/ preceded the member with /ts′/, we found robust priming, with effects that were comparable to those produced by identity priming (see Figure 6). These results converge with those of the prior priming studies and appear to suggest that even early and highly proficient non-native speakers treat the non-native sound (e.g., /tʂ′/) as though it were their closest-matching native sound (e.g., /ts′/).