Abstract

Human leukocyte antigen B (HLA-B) is responsible for presenting peptides to immune cells and plays a critical role in normal immune recognition of pathogens. A variant allele, HLA-B★57:01, is associated with increased risk of a hypersensitivity reaction to the anti-HIV drug abacavir. In the absence of genetic prescreening, hypersensitivity affects ∼6% of patients and can be life-threatening with repeated dosing. We provide recommendations (updated periodically at http://www.pharmkgb.org) for the use of abacavir based on HLA-B genotype.

The purpose of this guideline is to provide information that will allow the interpretation of clinical HLA-B genotype tests so that the results can be used to guide the use of abacavir for the treatment of HIV. Detailed guidelines regarding selection of appropriate antiretroviral therapy based on patient demographics and clinical measurements, viral resistance testing, and cost-effectiveness analyses, are beyond the scope of this article but are available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines are published and updated periodically on http://www.pharmgkb.org to reflect new developments in the field.

FOCUSED LITERATURE REVIEW

A systematic search of the literature focused on HLA-B genotype and abacavir use (see Supplementary Data online); reviews1–4 were relied on to summarize much of the earlier literature.

GENE: HLA-B

Background

HLA-B is a member of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene family located on chromosome 6, which consists of class I, II, and III subgroups. The HLA-B gene product is a class I HLA molecule that must heterodimerize with β-2 microglobulin to form a functional complex at the cell surface.5 HLA class I molecules are expressed on almost all cells and are responsible for presenting peptides to immune cells. Cells in the body are constantly producing new proteins, breaking down old proteins, and recycling the breakdown products into new proteins. However, some of these peptides are attached to MHC molecules instead, and are trafficked to the cell surface. In a typical cell, the peptides presented are the breakdown products of normal proteins and are recognized by immune cells as such (i.e., “self ”). However, if a cell becomes infected by a pathogen, some of the peptides presented will have resulted from the breakdown of foreign proteins and will be recognized as “non-self,” triggering an immune response against the antigen. MHC molecules are also critical in the field of transplant immunology, where careful HLA matching between donor and recipient minimizes transplant rejection.6 In addition, in rare cases, some pharmaceuticals are capable of producing immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions through interactions with MHC molecules, although the exact mechanism of these interactions remains unclear. Some suggest that these drugs may function as haptens that irreversibly bind to the peptides presented to immune cells, causing them to attack the peptide-hapten conjugate.7 Another theory suggests that these compounds might interact directly with MHC molecules or T-cell receptors, leading to T-cell activation.8

Because of the need to present a wide variety of peptides for immune recognition, HLA genes are both numerous and highly polymorphic.9 Other than in identical twins, the probability is extremely small that two individuals will be an exact HLA match across all loci. More than 1,500 HLA-B alleles have been identified, but the guidelines we present here specifically discuss only the HLA-B★57:01 allele as it relates to abacavir hypersensitivity reaction (HSR).

Genetic test interpretation

Clinical genotyping tests are available to identify HLA-B alleles. It is preferable to perform only specific tests for HLA-B★57:01 because more extensive HLA genotyping does not add clinically useful information with regard to abacavir treatment. Unlike many other pharmacogenetic associations, HLA-B allele status has no effect on abacavir pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetics; it only influences the likelihood that an HSR will occur. Furthermore, given the codominant expression of HLA-B, genotyping results are either “positive” (HLA-B★57:01 being present in one or both copies of the HLA-B gene) or “negative” (no copies of HLA-B★57:01 are present), with no intermediate phenotype. The assignment of the likely HLA-B phenotype, based on allele diplotypes, is summarized in Table 1. The prevalence pattern of HLA-B alleles varies significantly by population, and it has been extensively studied in geographically, racially, and ethnically diverse groups (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online). The frequency of the HLA-B★57:01 allele is lowest in African and Asian populations and is totally absent in some African populations as well as in the Japanese. In European populations, this allele is relatively common, with a frequency of 6–7%. The highest frequency of HLA-B★57:01 is reported in Southwest Asian populations, where up to 20% of the population are carriers.

Table 1.

Assignment of likely HLA-B phenotypes based on genotypes

| Likely phenotype | Genotypes | Examples of diplotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Very low risk of hypersensitivity (constitutes ∼94%a of patients) | Absence of *57:01 alleles (reported as “negative” on a genotyping test) | *X/*Xb |

| High risk of hypersensitivity (∼6% of patients) | Presence of at least one *57:01 allele (reported as “positive” on a genotyping test) | *57:01/*Xb *57:01/*57:01 |

HLA-B, human leukocyte antigen B.

See Supplementary Data online for estimates of genotype frequencies among different ethnic/geographic groups.

*X = any HLA-B genotype other than *57:01.

Available genetic test options

Several methods of HLA-B genotyping are commercially available. The Supplementary Data online and the Pharmacogenetic Tests section of PharmGKB (http://pharmgkb.org/resources/forScientificUsers/pharmacogenomic_tests.jsp) contain more information on available clinical testing options.

Incidental findings

Variations in HLA-B have been associated with several autoimmune conditions. For example, the presence of the HLA-B27 type is associated with development of ankylosing spondylitis,10 which commonly occurs alongside other inflammatory conditions, including uveitis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Despite decades of research, the causative mechanism for this is still unclear.

Several variants in HLA-B have been associated with other adverse drug reaction phenotypes. Patients with the HLA-B★15:02 genotype are at increased risk of developing Stevens–Johnson syndrome from treatment with carbamazepine,11 whereas HLA-B★58:01 is associated with an increased risk of severe cutaneous adverse reactions in response to allopurinol.12

In addition to abacavir HSR, HLA-B★57:01 has previously been linked to flucloxacillin-induced liver injury.13 Although the relative risk of liver injury was more than 40 times greater in HLA-B★57:01-positive patients than in HLA-B★57:01-negative ones, the incidence of flucloxacillin hepatotoxicity is rare (<1 in 5,000), significantly less than that of abacavir HSR; therefore routine screening for HLA-B★57:01 is not done to assess susceptibility to flucloxacillin-induced liver injury.

HLA-B★57:01 has also been shown to be overrepresented in HIV long-term nonprogressors,14,15 the small group of HIV-positive patients in whom, despite the absence of antiretroviral therapy, the condition does not progress to AIDS. This suggests that HLA-B★57:01 in some way confers a host immune response that is better able to control the virus. In addition, HLA-B★57:01 has been associated with a lower viral load set point (i.e., the amount of viral RNA detectable in blood during the asymptomatic period of HIV) in Caucasians;16 similar associations, with lower viral loads, have been observed in African Americans with the closely related allele HLA-B★57:03.17

DRUG: ABACAVIR

Background

Abacavir is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor indicated for the treatment of HIV infection, in combination with other medications, as part of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Abacavir competitively inhibits viral reverse transcriptase, suppressing HIV’s ability to convert its RNA genome into DNA before insertion into a host cell’s genome. It is commercially available as a single agent (Ziagen) or coformulated as a fixed-dose combination with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, lamivudine (Epzicom/Kivexa) and lamivudine/zidovudine (Trizivir). As compared with a tenofovir-based highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen, an abacavir-based one showed a significantly shorter time to virologic failure and also a shorter time to first adverse event in patients with baseline viral loads >100,000 copies/ml18 but showed no differences in virologic failure rates in patients with lower baseline viral loads. Abacavir received significant attention after the report of an association of the drug with an increased risk of myocardial infarction19 as compared with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; however, subsequent analyses,20 including a meta-analysis conducted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have failed to show any such association.

Although abacavir is generally well tolerated, ∼5–8% of patients experience HSR during the first 6 weeks of treatment if genetic prescreening is not performed. Symptoms of HSR increase in severity over time if the drug is continued despite the progressive symptoms. Symptoms of an HSR include at least two of the following: fever, rash, gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain), fatigue, cough, and dyspnea. Suspicion of an HSR warrants immediate discontinuation of abacavir. If the symptoms of clinically diagnosed HSR resolve after discontinuation of abacavir, drug rechallenge is contraindicated because immediate and life-threatening reactions, including anaphylaxis and even fatalities, can occur.21 In addition, an allergy to abacavir should be noted in the patient’s medical record. Previous data have shown that peripheral blood mononuclear cells from hypersensitive patients have a detectable immune response when cultured with abacavir in vitro,22,23 including increased expression of interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and other inflammatory cytokines, showing a clear role of the immune system in mediating abacavir HSR.

Linking genetic variability to variability in drug-related phenotypes

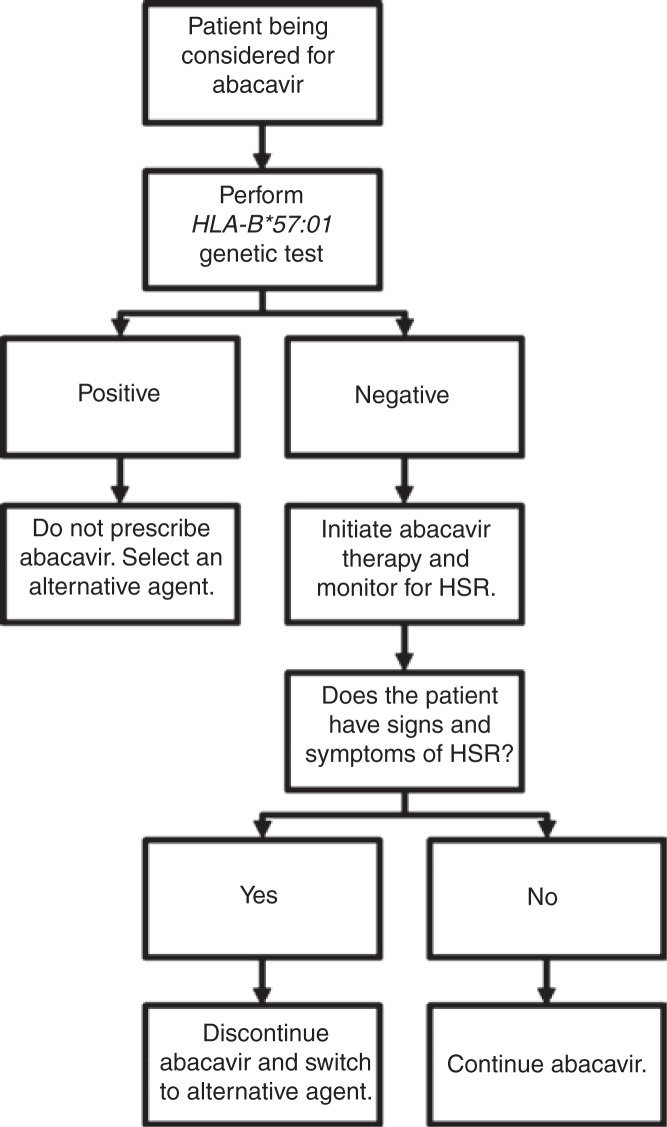

There is substantial evidence linking the presence of the HLA-B★57:01 genotype with phenotypic variability (see Supplementary Table S3 online). The application of a grading system to the evidence linking genotypic variability to phenotypic variability indicates a high quality of evidence in the majority of cases (see Supplementary Table S3). The evidence described below and in Supplementary Table S3 provides the basis for the recommendations in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for clinical use of abacavir based on HLA-B*57:01 genotype. HLA-B, human leukocyte antigen B; HSR, abacavir hypersensitivity reaction.

Table 2.

Recommended therapeutic use of abacavir in relation to HLA-B genotype

| Genotype | Implications for phenotypic measures | Recommendations for abacavir | Classification of recommendationsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noncarrier of HLA-B*57:01 | Low or reduced risk of abacavir hypersensitivity | Use abacavir per standard dosing guidelines | Strong |

| Carrier of HLA-B*57:01 | Significantly increased risk of abacavir hypersensitivity | Abacavir is not recommended | Strong |

HLA-B, human leukocyte antigen B.

Rating scheme described in Supplementary Data online.

In 2002, two independent research groups reported the initial association between HLA-B★57:01 and abacavir HSR24,25 using cohort and case–control designs. The association was replicated in a UK population in 2004.26 However, the results were not broadly generalizable because the populations studied were predominantly white males. Nevertheless, given the strength of the observed association, some centers began implementing prospective screening of HLA-B★57:01 in all HIV-positive patients to exclude HLA-B★57:01 positivity before starting abacavir. This approach led to significant reductions in the incidence of HSR.27–29 These studies, along with the retrospective SHAPE study,30 found that HLA-B★57:01 was also predictive of HSR in females and in African Americans.

Moreover, the results of PREDICT-1, the first double-blind, prospective, randomized trial of a genetic test to reduce adverse drug events, showed that genetic prescreening for HLA-B★57:01 resulted in no immunologically confirmed HSR events among HLA-B★57:01-negative patients in the genetic testing arm,31 vs. a 2.7% incidence of immunologically confirmed HSR among 842 unscreened patients in the standard-of-care control arm. The results of PREDICT-1 and the existing body of evidence prompted the FDA to implement a black box warning in 2008 about the high risk of HLA-B★57:01-associated HSR. The FDA recommended that all patients be screened before being treated with abacavir (including those who had previously tolerated the drug and were being restarted on the therapy) and that abacavir not be initiated in carriers of HLA-B★57:01. Abacavir is one of a limited number of drugs for which the FDA has recommended genetic testing prior to use, and it remains one of the best examples to date of pharmacogenetics being integrated into routine medical practice.

Therapeutic recommendations

We agree with others32–36 that HLA-B★57:01 screening should be performed in all abacavir-naive individuals before initiation of abacavir-containing therapy (see Table 2); this is consistent with the recommendations of the FDA, the US Department of Health and Human Services, and the European Medicines Agency. In abacavir-naive individuals who are HLA-B★57:01-positive, abacavir is not recommended and should be considered only under exceptional circumstances when the potential benefit, based on resistance patterns and treatment history, outweighs the risk. HLA-B★57:01 genotyping is widely available in the developed world and is considered the standard of care prior to initiating abacavir. Where HLA-B★57:01 genotyping is not clinically available (such as in resource-limited settings), some have advocated initiating abacavir, provided there is appropriate clinical monitoring and patient counseling about the signs and symptoms of HSR, although this remains at the clinician’s discretion.

There is some debate among clinicians regarding whether HLA-B★57:01 testing is necessary in patients who had previously tolerated abacavir chronically, discontinued its use for reasons other than HSR, and are now planning to resume abacavir. The presence of HLA-B★57:01 has a positive predictive value of ∼50% for immunologically confirmed hypersensitivity,31 indicating that some HLA-B★57:01-positive individuals can be, and have been, safely treated with abacavir. However, we were unable to find any data to show that HLA-B★57:01-positive individuals with previous, safe exposure to abacavir had zero risk of HSR upon re-exposure. Although there are isolated case reports of previously asymptomatic patients developing a hypersensitivity-like reaction after restarting abacavir,37–39 there were confounding circumstances. Many of the patients had complicating concomitant illnesses that could have masked an HSR during initial abacavir therapy, and none were immunologically confirmed, making the case reports difficult to interpret. Furthermore, most of these case reports precede the availability of HLA-B★57:01 genetic testing, making it impossible to determine from the published data whether there could be a risk of HSR upon re-exposure to abacavir in previously asymptomatic HLA-B★57:01-positive patients.

In addition, there may also exist a small group of patients who have been on chronic abacavir therapy since before the introduction of HLA-B★57:01 genotyping. Given that virtually all abacavir HSR events occur within the first several weeks of therapy, and that ∼50% of HLA-B★57:01 carriers can safely take abacavir, we were unable to find any evidence to suggest that HLA-B★57:01-positive individuals on current, long-term, uninterrupted abacavir therapy are at risk of developing HSR. Existing clinical guidelines32–36 have a blanket recommendation that all HLA-B★57:01-positive individuals should avoid abacavir, regardless of patient history. Although HLA-B★57:01 genotyping has proven utility in significantly reducing the incidence of both clinically diagnosed and immunologically confirmed hypersensitivity7,27,28,31,40 in patients being newly considered for abacavir therapy, the connection between HLA-B★57:01 genotype and risk of HSR in patients with previous asymptomatic abacavir use is less clear.

Recommendations for incidental findings

Although other variants in HLA-B are associated with autoimmune diseases and drug response phenotypes, they have not been associated with abacavir HSR.

Other considerations

Abacavir skin patch testing may be performed after a case of clinically diagnosed HSR to determine whether it can be immunologically confirmed. At this time, skin patch testing is an investigational procedure, and the results should be interpreted only by an experienced immunologist. More details on skin patch testing can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods online.

Potential benefits and risks for the patient

A clear benefit of HLA-B★57:01 testing is that it leads to a reduction in the incidence of abacavir HSR by identifying patients at significant risk so that alternative antiretroviral therapy can be prescribed for them. Importantly, a number of effective and safe antiretrovirals are available that can be substituted for abacavir in patients carrying this risk-related allele. HLA-B★57:01’s high negative predictive value (>99%)31 shows that it is extremely effective in identifying those at risk of immunologically confirmed hypersensitivity to abacavir. A potential problem would be an error in genotyping or in reporting a genotype. This could result in high-risk patients mistakenly being given abacavir and potentially having an HSR. However, given that patients testing negative for HLA-B★57:01 also have a 3% risk of developing a clinically diagnosed HSR, standard practice would include patient counseling and careful monitoring for signs and symptoms of an HSR. Given the lifelong nature of genotype results, an error in genotyping may also have a broader adverse impact on a patient’s health care if other associations with HLA-B★57:01 are found in the future.

Caveats: appropriate use and/or potential misuse of genetic tests

The positive predictive value of HLA-B★57:01 genotyping is ∼50%, which means that a significant number of patients will be denied abacavir on the basis of their genotyping results even though they would have been able to take abacavir without experiencing an HSR. There is currently no way to know a priori which HLA-B★57:01 carriers are and which are not likely to experience HSRs, although new genetic risk factors may be found in the future. Given the potential seriousness of HSRs, the moderate positive predictive value is greatly outweighed by the very high negative predictive value of HLA-B★57:01 genotyping.

HLA-B★57:01 is not predictive of any other adverse reactions a patient may experience while on abacavir treatment, nor does it predict whether abacavir will be effective in treating a patient’s HIV. In addition, genotyping is not a replacement for appropriate patient education and clinical monitoring for the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity. The development of signs and symptoms of an HSR warrants that serious consideration be given to discontinuing abacavir, regardless of the HLA-B genotyping results.

Disclaimer

CPIC guidelines reflect expert consensus based on clinical evidence and peer-reviewed literature available at the time they are written and are intended only to assist clinicians in decision making and to identify questions for further research. New evidence may have emerged since the time a guideline was submitted for publication. Guidelines are limited in scope and are not applicable to interventions or diseases not specifically identified. Guidelines do not account for all variations among individual patients and cannot be considered inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other treatments. It remains the responsibility of the health-care provider to determine the best course of treatment for the patient. Adherence to any guideline is voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding its application to be made solely by the clinician and the patient. CPIC assumes no responsibility for any injury to persons or damage to property related to any use of CPIC’s guidelines, or for any errors or omissions.

Supplemental Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/cpt

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the critical input of members of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was funded by NIH grants GM61390 and GM61374.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chung WH, Hung SI, Chen YT. Human leukocyte antigens and drug hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:317–323. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282370c5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatanaga H, Honda H, Oka S. Pharmacogenetic information derived from analysis of HLA alleles. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:207–214. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes AR, et al. Pharmacogenetics of hypersensitivity to abacavir: from PGx hypothesis to confirmation to clinical utility. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8:365–374. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips EJ, Mallal SA. Pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:973–987. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, Wearsch PA. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurley CK, et al. National Marrow Donor Program HLA-matching guidelines for unrelated marrow transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin AM, et al. Predisposition to abacavir hypersensitivity conferred by HLA-B*5701 and a haplotypic Hsp70-Hom variant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4180–4185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307067101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam J, Pichler WJ, Yerly D. Delayed drug hypersensitivity: models of T-cell stimulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:701–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiina T, Hosomichi K, Inoko H, Kulski JK. The HLA genomic loci map: expression, interaction, diversity and disease. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:15–39. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas GP, Brown MA. Genetics and genomics of ankylosing spondylitis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:162–180. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung WH, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004;428:486. doi: 10.1038/428486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung SI, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly AK, et al. DILIGEN Study. International SAE Consortium HLA-B*5701 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin. Nat Genet. 2009;41:816–819. doi: 10.1038/ng.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein MR, et al. Characterization of HLA-B57-restricted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag- and RT-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Gen Virol. 1998;79(Pt 9):2191–2201. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Migueles SA, et al. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2709–2714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050567397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fellay J, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV-1. Science. 2007;317:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1143767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelak K, et al. Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working Group. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology (CHAVI) Host determinants of HIV-1 control in African Americans. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1141–1149. doi: 10.1086/651382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sax PE, et al. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5202 Team Abacavirlamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine for initial HIV-1 therapy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2230–2240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabin CA, et al. D:A:D Study Group Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008;371:1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60423-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedimo RJ, Westfall AO, Drechsler H, Vidiella G, Tebas P. Abacavir use and risk of acute myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:84–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hetherington S, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions during therapy with the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1603–1614. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin AM, et al. Immune responses to abacavir in antigen-presenting cells from hypersensitive patients. AIDS. 2007;21:1233–1244. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280119579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almeida CA, et al. Cytokine profiling in abacavir hypersensitivity patients. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2008;13:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallal S, et al. Association between presence of HLA-B*5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:727–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hetherington S, et al. Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:1121–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes DA, Vilar FJ, Ward CC, Alfirevic A, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of HLA B*5701 genotyping in preventing abacavir hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:335–342. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauch A, Nolan D, Martin A, McKinnon E, Almeida C, Mallal S. Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:99–102. doi: 10.1086/504874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waters LJ, Mandalia S, Gazzard B, Nelson M. Prospective HLA-B*5701 screening and abacavir hypersensitivity: a single centre experience. AIDS. 2007;21:2533–2534. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328273bc07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zucman D, Truchis P, Majerholc C, Stegman S, Caillat-Zucman S. Prospective screening for human leukocyte antigen-B*5701 avoids abacavir hypersensitivity reaction in the ethnically mixed French HIV population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:1–3. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318046ea31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saag M, et al. Study of Hypersensitivity to Abacavir and Pharmacogenetic Evaluation Study Team High sensitivity of human leukocyte antigen-b*5701 as a marker for immunologically confirmed abacavir hypersensitivity in white and black patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1111–1118. doi: 10.1086/529382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallal S, et al. PREDICT-1 Study Team HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gazzard BG, et al. BHIVA Treatment Guidelines Writing Group British HIV Association Guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-infected adults with antiretroviral therapy 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:563–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aberg JA, et al. HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:651–681. doi: 10.1086/605292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-infected Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. pp. 1–166. < http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becquemont L, et al. Practical recommendations for pharmacogenomics-based prescription: 2010 ESF-UB Conference on Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:113–124. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swen JJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte–an update of guidelines. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:662–673. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loeliger AE, Steel H, McGuirk S, Powell WS, Hetherington SV. The abacavir hypersensitivity reaction and interruptions in therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1325–1326. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frissen PH, de Vries J, Weigel HM, Brinkman K. Severe anaphylactic shock after rechallenge with abacavir without preceding hypersensitivity. AIDS. 2001;15:289. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101260-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahly HME. Development of abacavir hypersensitivity reaction after rechallenge in a previously asymptomatic patient. AIDS. 2004;18:359–360. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young B, et al. First large, multicenter, open-label study utilizing HLA-B*5701 screening for abacavir hypersensitivity in North America. AIDS. 2008;22:1673–1675. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830719aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.