Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to test a new problem-based learning (PBL) method to see if it reinvigorated the learning experience.

Method

A new PBL format called PBL 2.0, which met for 90 min two times per week, was introduced in 2009 into an 11-week integrated neuroscience course. One hundred second-year medical students, divided into 10 groups of 10, who had completed their first year of medical school using a traditional PBL format, participated in PBL 2.0. Students were prohibited from using computers during the first session. Learning objectives were distributed at the end of the first day to the small groups, and students were assigned to pairs/trios responsible for leading an interactive discussion on specific learning objectives the following day. Student-led ‘lectures’ were prohibited. All students were responsible for learning all of the learning objectives so that they could participate in their discussions.

Results

One hundred and six students were surveyed and 98 submitted answers (92% response). The majority of groups adhered to the new PBL method. Students invested more time preparing the learning objectives. Students indicated that the level of interaction among students increased. The majority of students preferred the new PBL format.

Conclusions

PBL 2.0 was effective in increasing student interaction and promoting increased learning.

Keywords: problem-based learning, learning strategies, medical education, problem solving, critical thinking, problem-based curriculum

In many US medical schools in the last several decades, problem-based learning (PBL) has changed the way basic science and clinical education are provided (1). PBL is an instructional method that uses clinical problems as a context for students to learn problem-solving skills and to acquire biomedical knowledge. Instead of rote memorization and short-term learning strategies more common to lecture formats, PBL provides a student-centered learning environment, encourages curiosity (2), and involves a multistep process. First, students encounter a problem and try to solve it with their current fund of knowledge and clinical reasoning. Second, they identify learning objectives and research the objectives individually. Finally, the students apply their newly gained knowledge to solve the problem and summarize what has been learned (1, 3).

Studies evaluating the efficacy of PBL have been inconclusive. Some have demonstrated that PBL enhances students’ intrinsic interest in the subject matter, strengthens students’ self-directed learning skills (4), and is more nurturing and enjoyable (3). Students who use PBL as a major pedagogic method in their curriculum rated their medical education programs higher than students from traditional curricula (5). PBL ‘graduates’ have performed as well on clinical and written examinations (3) and on miscellaneous tests of factual knowledge (5), but recent reviews of PBL have not been able to show that PBL improves test scores or student performance on clinical rotations (6). Studies have demonstrated that PBL does not improve knowledge acquisition, but that PBL may increase the long-term retention of knowledge (4, 7, 8). Recent reviews of PBL have identified that group-based problem solving encourages the activation of prior knowledge and facilitates the comprehension of new information and improves the critical thinking of students (9, 10).

Many institutions have found the PBL method that has been used over the years to become stale. At our institution, in the pre-intervention format, students and faculty voiced concern that students fall into a habit of focusing on the research and delivery of their individual presentations on a particular learning objective, while becoming disengaged from the overall ‘big picture’ concepts and interactive problem solving that make PBL beneficial to the learning process. Students had come to believe that PBL faculty facilitators were evaluating them on the quality of their individual 5–10 min presentations, and therefore devoted the bulk of their preparation time to learning their particular objective in detail. In this way, PBL had become ritualized as students delivered overly detailed presentations, and ‘tuned out’ when their peers were presenting. Interactive broad-based learning was sacrificed, as students may be experts on their own individual topics. However, students lacked the knowledge to participate in discussion of their peer's presentations.

In order to return to the team-oriented problem-solving origins of PBL, students and faculty designed and implemented key changes in PBL to the WCMC curriculum termed PBL 2.0. These changes were evaluated by administering an eight-question survey to assess four domains: to what extent PBL groups adhered to the new format, how much additional time students invested in outside preparation/studying, students’ self-assessment of their learning with the new format, and how they felt about the new learning environment.

Methods

Setting

Students and faculty identified an 11-week course called Brain and Mind which has a PBL component. Brain and Mind is an integrated course that covers neuroscience, neuroanatomy, pharmacology, clinical neurology, and psychiatry. The course uses a variety of learning modalities, including lectures, patient presentations, small-group tutorials, journal club sessions, patients in clinical settings, and laboratory sessions on neuroanatomy. The problem-based learning component of the course covers common neurological and psychiatric disorders, many of which are not covered in course lectures.

The structure of PBL in this course involves 10 groups of 10 second-year students and one or two neurology or psychiatry faculty facilitators per group. Each PBL group meets for two 90-min sessions per week. On the first day, a clinical case is distributed and discussed in sequential parts of an unfolding case history. Learning objectives are assigned to each of the 10 students at the end of the first session. In the past, on the second day, each student would deliver a presentation on his or her assigned learning objective, occasionally giving powerpoint presentations or distributing handouts. At the conclusion of each two-session PBL, a faculty member conducts a 30-min expert session emphasizing the key learning objectives of the case to the entire class.

Intervention

To improve the learning climate, foster greater engagement by students, increase collegiality within the group, improve the learning of key concepts, and incentivize positive learning behaviors, several changes were made to Brain and Mind PBL.

On the first day, the case was distributed in its usual manner. One student would serve as a reader and another would act as a scribe who organized details on the classroom whiteboard. In PBL 2.0, students were prohibited from using computers on the first day, as it was found that students would search keywords to solve the case, bypassing the problem solving and reasoning exercise of PBL. At the end of the first day, learning objectives, reduced to 4–6, were distributed to the group, and students were assigned or self-assigned to pairs/trios to serve as a sub-group responsible for leading a discussion on specific learning objectives the following session. The learning objectives are topics that cover very specific concepts related to a case such as the diagnostic process, common symptomology, treatment methods and patient's prognosis, and most learning objectives that students derived before the official list was distributed fell into these categories.

Each pair or trio was expected to prepare their learning objective into a collective problem-solving exercise and to take an active role in participating in the second session by researching all of the remaining learning objectives. To make this expectation more realistic, the number of learning objectives was reduced through deletion and consolidation (from 10 to between 4 and 6).

On the second day, the student pairs/trios formulated 4 or 5 key talking points about their assigned learning objective that were posed to the group. Presenters were responsible for formulating important points to facilitate a discussion that was to be illuminating and thought provoking. The pair/trio was not supposed to lecture, use powerpoint or give out extensive written information. Instead, discussion points were to be conveyed verbally or through the use of white boards. The pair/trio was encouraged to ask questions of their fellow students to stimulate an interactive discussion. As each student had prepared all of the learning objectives, each was able to participate in each of the others pair/trio's discussion. The facilitator's role was to correct factual errors, elucidate some important areas that may not have been fully discussed and manage time spent on the presentations.

Students were assessed based on their preparation for class, participation in both the analysis of the case and discussion of learning objectives, their ability to work with colleagues, and to formulate important points for a discussion. Facilitators were instructed to note students who failed to prepare each learning objective and remained silent, as well as students who gave ‘lectures’ instead of fostering a discussion. Facilitators were also instructed not to dominate the session, nor to give lectures. The amount of classroom time was kept the same.

Implementation of intervention

Since students and faculty were already experienced with the pre-intervention format of PBL, it was important to explicitly state the goals of the new PBL format. Both faculty and students received orientations on the new format and the amended system. A faculty meeting was held in which faculty facilitators were instructed to evaluate students on the basis of their contributions to group problem solving and their ability to stimulate group discussion on learning objectives. It was made clear that students were not supposed to lecture the group. Likewise, a student orientation was held in which the new format was explained and the same instructions were provided to students. To underscore how different the expectations were for both faculty and students, PBL was called PBL 2.0.

Survey

At the conclusion of the course, students were asked to complete a survey to evaluate their satisfaction with PBL 2.0. Students were asked eight questions regarding PBL, and were asked to compare the new version of PBL to their past experiences. The questions assessed four domains: the degree to which they thought their PBL group adhered to the new format, their assessment of time investment researching learning objectives and preparing presentations in the new format, their self-assessment of their learning with the new format, and how they felt about the learning environment in PBL 2.0.

Statistical analysis

A three-point Likert scale was used for question 1, and a five-point Likert scale was used for questions 2–8. For the purposes of data analysis and presentation, the responses were grouped into ‘Agree,’ ‘Neutral,’ and ‘Disagree.’

Results

The survey was distributed to 106 students, and 98 submitted answers (92% response). Group compliance with the new PBL format was significant, as 81% of students answered that their groups either adhered somewhat to or strongly to the new format. Our survey method did not allow separate analysis within individual PBL groups, so the intra-group variability is unknown.

Regarding student time invested in preparing for learning objectives, 62% of students spent more time preparing all of the learning objectives compared to their previous PBL experiences. There was little change in how much time student leaders spent preparing their own learning objectives compared to ‘traditional’ PBL, as 47% of students spent the same amount of time preparing their assigned objective as compared to last year, 30% spent ‘less’ or ‘much less’ time on their own objectives, whereas 22% spent ‘more’ or ‘much more.’ Students indicated that the level of interaction was increased, as 43% answered that the majority of the presentation time was interactive, and 59% found that the group worked better through the case.

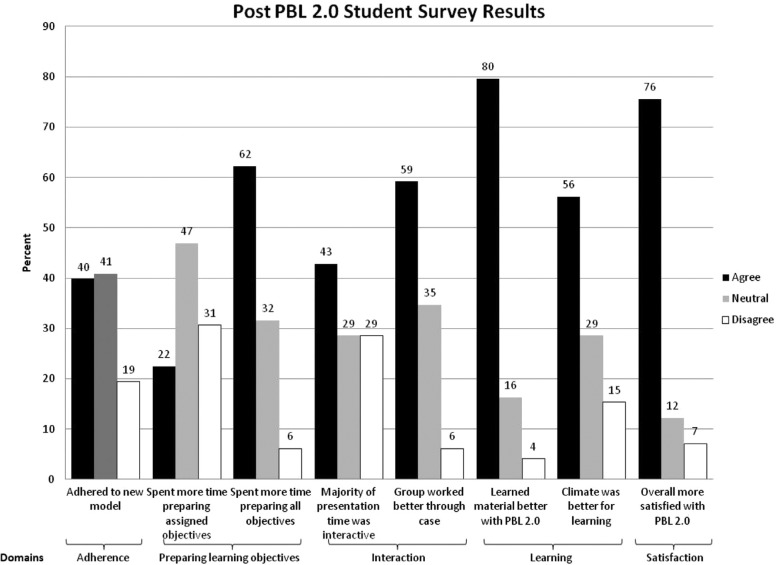

Regarding the student learning experience, over 80% indicated that they learned the material better with PBL 2.0, and 56% indicated that PBL 2.0 provided a better climate for learning. Overall, 75% of students preferred PBL 2.0 to the old format, while 12% were indifferent. Only 7% preferred the old format. The majority of students were satisfied overall with PBL 2.0 (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Post-intervention PBL 2.0 student survey results.

Discussion

In this study, we implemented several changes to the PBL format in an effort to improve upon what had become a stale and ritualized learning environment. The principal findings are that students thought PBL 2.0 was more interactive, students invested more time in learning and preparing the material, the group process worked better, and students and faculty were overall satisfied.

Our experience indicates that the key ingredient is increased participation. Problem-based learning works best when students are engaged in a dynamic way while working through a case. In order for this interaction to occur, all students must be prepared to discuss the learning objectives for the case. While this involves more work outside of the classroom, it improves the PBL climate exponentially and ultimately leads to better understanding and greater retention of the concepts. PBL 2.0 increased the collegiality of students, by encouraging them to prepare their presentations in groups of 2–3 students instead of working individually. The format of PBL 2.0 required students to increase their interaction with their peers rather than to listen to them during their second day review of the learning objectives. In order for students to participate effectively, they realized they must bolster their fund of knowledge prior to their second day discussions.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, fidelity to the PBL 2.0 model was not perfect. Twenty percent of respondents said they did not adhere at all to the new PBL model, and feedback indicates that some faculty members who had been facilitating PBL for several years had difficulty transitioning to the new model.

Second, it was not possible to conduct a randomized trial of the old and new PBL methods, so students were comparing PBL from a first-year course to PBL in a second-year course. This introduces a recall bias based on a past year comparison. That being said, students were asked to specifically compare their PBL experiences rather than their enjoyment of the course overall in order to reduce this source of bias.

Third, it is difficult to objectively assess whether PBL 2.0 improved learning. Perhaps future studies could administer an assessment quiz after PBL sessions in a case–control manner to add objective evidence of achievement to the student's self-assessment of their own learning.

We do not believe that PBL has to be conducted with a strict methodology developed 40 years ago to be effective. Curriculum administrators need to be willing to make PBL flexible and dynamic, as PBL should evolve to meet the needs of the curriculum, especially at a time when information services are rapidly changing. However, from the results of our study, we have identified key characteristics that we believe each PBL curriculum should embrace. First, PBL thrives when students solve problems in an interactive environment. Second, PBL is reliant on the collective knowledge of a group of students who interactively solve problems and learn from each other. To facilitate this, we encourage students to prepare all learning objectives so students can contribute meaningfully to discussions. Third, grading incentives can facilitate good student behavior, as facilitators were instructed to evaluate students on their contributions to the discussion and problem solving rather than their ability to deliver stock lectures.

Problem-based learning is an extraordinarily valuable tool for teaching the basic and clinical sciences. As it is increasingly used in medical schools across the country, it is important that PBL maximizes learning. We believe the changes we made to our PBL curriculum are critical for the success of PBL as a learning modality at WCMC.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the WCMC Brain and Mind faculty for facilitating the PBL sessions.

Conflict of interest and funding

There are no conflicts of interest for this research. No outside sources of funding were accessed for this study.

Ethical approval

Weill Cornell Medical College's Institutional Review Board determined that the research project met exemption requirements under protocol number EXE-2011-031, HHS 45 CFR 46.404(b).

References

- 1.Barrows HS. Problem based learning: an approach to medical education. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1980. p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt HG, Dauphinee WD, Patel VL. Comparing the effects of problem-based and conventional curricula in an international sample. J Med Educ. 1987;62:305–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albanese MA, Mitchell S. Problem-based learning: a review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad Med. 1993;68:52–81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: a review of the evidence. Acad Med. 1992;67:557–65. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernon DT, Blake RL. Does problem-based learning work? A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad Med. 1993;68:550–63. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polyzois I, Claffey N, Mattheos N. Problem-based learning in academic health education. A systematic literature review. Eur J Dent Educ. 2010;14:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkson L. Problem-based learning: have the expectations been met? Acad Med. 1993;68(10 Suppl):S79–88. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199310000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartling L, Spooner C, Tjosvold L, Oswald A. Problem-based learning in pre-clinical medical education: 22 years of outcome research. Med Teach. 2010;32:28–35. doi: 10.3109/01421590903200789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt HG, Rotgans JI, Yew EH. The process of problem-based learning: what works and why. Med Educ. 2011;45:792–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oja KJ. Using problem-based learning in the clinical setting to improve nursing students’ critical thinking: an evidence review. J Nurs Educ. 2011;50:145–51. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20101230-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]