Abstract

Signal transduction and endocytosis are intertwined processes. The internalization of ligand-activated receptors by endocytosis has classically been thought to attenuate signals by targeting receptors for degradation in lysosomes, but it can also maintain signals in early signalling endosomes. In both cases, localization to multivesicular endosomes en route to lysosomes is thought to terminate signalling. However, during WNT signal transduction, sequestration of the enzyme glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) inside multivesicular endosomes results in the stabilization of many cytosolic proteins. Thus, the role of endocytosis during signal transduction may be more diverse than anticipated, and multivesicular endosomes may constitute a crucial signalling organelle.

The role of endocytosis in signal transduction has been known and debated for many years. After endocytosis, signalling receptors and their factors are targeted to endosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and eventually fuse to lysosomes to be degraded. Thus, the established view has been that the internalization of most growth factor receptors bound to their ligands constitutes a way to downregulate activated receptors and attenuate the signal1,2.

In this model, internalized vesicles mature into MVBs, which then fuse with lysosomes to allow degradation of their content. This was first shown in early work by Cohen3, who observed that epidermal growth factor (EGF) coupled to ferritin was rapidly internalized upon binding to EGF receptor (EGFR) and found inside MVBs after only 15 minutes exposure of cells to ligand. MVBs form as endosomes mature, through invagination of small intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of about 50 nm in diameter (BOX 1), which then pinch off. This requires the help of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery2,4, the components of which were first identified in budding yeast as Vps (vacuolar protein sorting) mutants1 and regulate membrane scission during ILV formation.

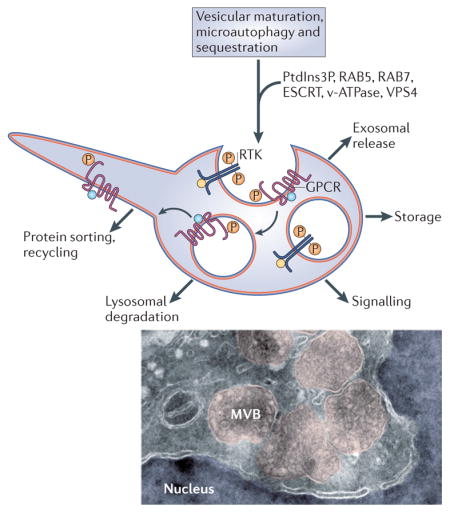

Box 1. Biogenesis and functions of multivesicular endosomes.

Multivesicular endosomes are characterized by the internalization of small intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of about 50 nm in diameter. This requires the orderly recruitment of components of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery4,70. In addition, ILV formation requires the endosome-specific lipid phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P), and the AAA-ATPase vacuolar protein sorting-associated 4 (VPS4) to pinch-off the vesicles71,72. The matrix of endosomes is gradually acidified by vacuolar ATPases (v-ATPases) as they undergo maturation, enlarge and convert the early RAB5-positive compartments into RAB7-positive late endosomes73,74. The lumen of early recycling endosomes has a pH of 6.5–6.4 (compared with pH 7.2 in the cytosol), that of late multivesicular endosomes has a pH of 6.0–5.0 and, after fusing with lysosomes, a pH of 5.0–4.5 is reached75,76. Lysosomal hydrolases degrade proteins and lipids at acid pH.

The diverse functions of multivesicular endosomes are indicated in the figure. In addition to serving as precursors for lysosomal degradation77,78, ILVs can be released into the extracellular space as exosomes when the entire organelle fuses to the plasma membrane79–81. The sequestered proteins can also be transiently stored and recycled back to the cytoplasm or the plasma membrane via ‘back-fusion’ of ILVs to the peripheral endosomal membrane82 and membrane recycling through tubular structures23. Membrane proteins are sorted into ILVs after becoming monoubiquitylated6. Cytosolic material can be engulfed into multivesicular endosomes by microautophagy, which involves invagination of larger vesicles containing cytoplasmic components, such as ribosomes83. The electron micrograph illustrates the morphology of multivesicular bodies (MVBs; shadowed in pink). These MVBs were induced by a constitutively active form of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related 6 (LRP6) receptor that generates a very strong WNT signal by sequestering glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) inside these structures12. RTK, receptor Tyr kinase; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor. The cryoelectron microscopy image is courtesy of D. D. Sabatini, New York University, USA.

Today, we realize that membrane trafficking has additional functions in cell signalling beyond signal attenuation. The recent demonstration that WNT signalling triggers glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) sequestration into MVBs, allowing the activation of cytosolic proteins, raises the possibility that MVBs may have unanticipated roles in signal regulation. Here, we suggest that this mechanism may be physiologically relevant during axis differentiation in vertebrate embryos. Moreover, we propose that this may reflect a more general regulatory role of MVBs in other signalling pathways, in which activated cell surface receptors may entrap inhibitory enzymes and/or adaptor proteins bound to their cytoplasmic domains inside the ILVs of multivesicular endosomes. In each case, the identity of the co-sequestered protein will depend on the type of growth factor and receptor bound to it. We discuss the evidence that supports this model from studies of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), JAK–STAT (Janus-activated kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription) and Notch signalling pathways, and suggest that cytosolic proteins other than GSK3 could potentially also be depleted through sequestration in MVBs in a growth factor-dependent manner. We propose that multi-vesicular endosomes are not mere lysosomal precursors but signalling organelles.

Broad effects of endocytosis on signalling

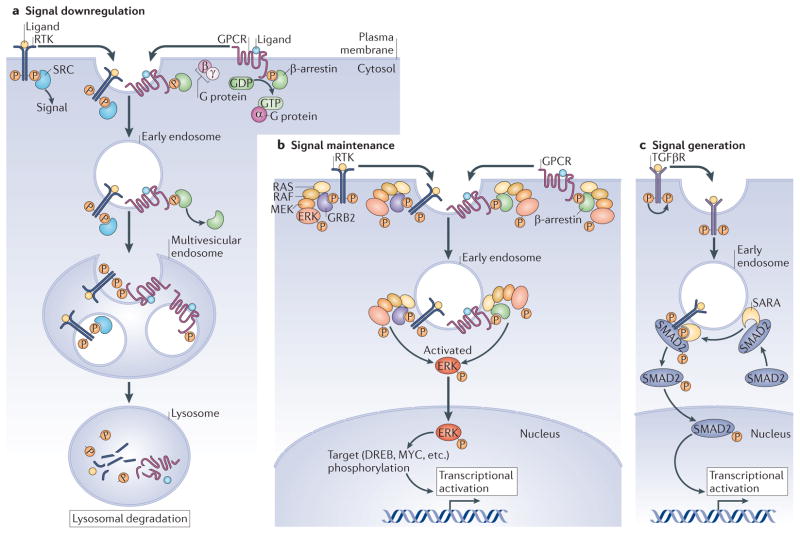

Although endocytosis was for many years considered as only a means of limiting signal transduction, it has since emerged that endocytosis has additional roles in maintaining and even generating specific signals (FIG. 1). It has become clear that some receptors continue to signal on internal membranes, such as endosomes, providing a further possibility for the spatial control of signalling events.

Figure 1. Current models for the intersection between endocytosis and signalling pathways.

There are three major models for the crosstalk between endocytosis and cell signalling. a | Downregulation of signals through the degradation of receptor complexes. Receptor Tyr kinases (RTKs) and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) signal at the plasma membrane through their effectors, such as SRC (for RTKs) and β-arrestin or activated G proteins (for GPCRs), which are then released as the receptors become internalized into early endosomes that undergo acidification. After trafficking of receptors into the intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of multivesicular endosomes, these organelles fuse with lysosomes and the receptors are degraded. b | The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway provides an example in which signalling downstream of RTKs or GPCRs can be maintained by early endosomes. The signal is generated at the plasma membrane and continues signalling in early endosomes through formation of RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK (RAS–RAF–MAPK/ERK kinase (also known as MAPKK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase) complexes bound to the growth factor receptor-bound 2 (GRB2) adaptor for RTKs or β-arrestin for GPCRs. Activated ERK is released from the endosome and translocates to the nucleus to phosphorylate its targets. c | For signalling downstream of transforming growth factor-β receptor (TGFβR), as well as other receptors, the signal is actually generated on signalling endosomes. The ligand-bound TGFβR is internalized into endosomes upon phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic tail. SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA) is an FYVE domain (phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate-binding) protein that recognizes this activated receptor and recruits the SMAD2 transcription factor to signalling endosomes. Phosphorylated SMAD2 is then released, entering the nucleus to promote transcriptional activation.

Signal downregulation

A well-characterized example of receptor down-regulation through endocytosis occurs during signalling through receptor Tyr kinases (RTKs) or GPCRs. The signal is initiated at the plasma membrane through the binding of an effector protein (for example, SRC or GRB (growth factor receptor-bound) to an RTK or a G protein to a GPCR). In order to attenuate the signal, the receptors must be internalized into the ILVs of MVBs (REF. 2) before they can be degraded in lysosomes (FIG. 1a). Through this well-studied mechanism, endocytosis attenuates the activation of signal effectors by removing active receptors from the membrane5,6.

Signal maintenance

Some receptors can signal away from the plasma membrane, with endosomal membranes acting as signalling platforms. In the case of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling, the binding of RTK to GRB2, or of GPCR to β-arrestin, triggers the assembly of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-activating complexes (FIG. 1b). ERK is phosphorylated while the receptors are still on the plasma membrane but remains active on the surface of internalized early endosomes, also called signalling endosomes or signalosomes (FIG. 1b). Phosphorylated ERK is then released from the endocytic surface and enters the nucleus to activate its targets, inducing transcriptional activation7–9 (FIG. 1b). Continued activation of ERK at the endosomal membrane allows maintenance of MAPK signalling during endocytosis. Thus, endocytosis of the receptor complexes does not always result in signal attenuation but can cause sustained signalling. Endosome-specific signalling events can also start at the plasma membrane6.

Generation of signals

In some cases, specific signalling events require factors to be brought together by endocytosis. For example, during transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signalling, ligand-bound receptors become phosphorylated at Ser residues and are internalized by endocytosis. Once localized into endosomes, TGFβ receptor (TGFβR) can bind to SMAD anchor for receptor activation (SARA), and BMP receptor (BMPR) can bind to the related protein endofin. These complexes present the transcription factors SMAD1 or SMAD2 to be phosphorylated by their Ser/Thr kinase receptors10,11 (FIG. 1c). Upon phosphorylation, SMADs are released into the cytoplasm, bind a cofactor (SMAD4), enter the nucleus and promote gene transcription (FIG. 1c). This type of endosome-specific signalling may also apply to a wide range of other pathways, including signalling through GPCRs, RTKs, Notch and tumour necrosis factor6.

The sequestration model

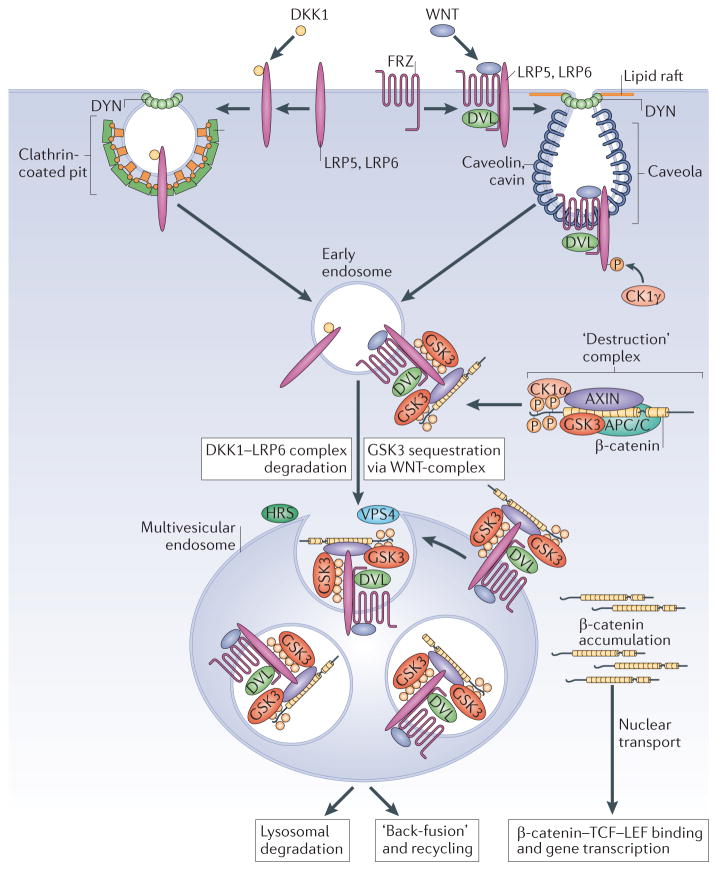

A common feature of the three models described above for how endosomes can affect signalling is that signal transduction is terminated when the signalling complexes are engulfed in the ILVs of MVBs: they are subsequently degraded in lysosomes (BOX 1). In contrast to this, we have recently reported a new mechanism by which the sequestration of an enzyme from the cytosol inside the ILVs of MVBs actually generates the signal12 (FIG. 2).

Figure 2. Endocytosis is required for canonical WNT signalling.

Two WNT co-receptors, Frizzled (FRZ) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related 6 (LRP6), are required in the plasma membrane for canonical WNT signalling. When cells are exposed to the antagonist Dickkopf homologue 1 (DKK1), LRP6 is directed to endocytosis by clathrin-coated vesicles, becoming inactive and subsequently degraded through multivesicular body (MVB)-mediated delivery to lysosomes27. Conversely, when the cell receives a WNT signal, WNT binds to both LRP6 and FRZ. This recruits Dishevelled (DVL), which is required for polymerization of the co-receptors in lipid rafts and endocytosis through caveolin-containing vesicles13. This internalization also requires the endocytosis effector Dynamin (DYN) and vacuolar ATPase (v-ATPase)21,84. The cytoplasmic tail of LRP6 is phosphorylated by casein kinase 1γ (CK1γ) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), activating endocytosis85 and binding components of the β-catenin ‘destruction’ complex (axis inhibition protein (AXIN) and GSK3). Early endosomal vesicles mature into multivesicular endosomes (in a process that requires hepatocyte growth factor-regulated Tyr kinase substrate (HRS) and vacuolar protein sorting-associated 4 (VPS4)) and WNT receptor complexes are internalized, sequestering GSK3 inside intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). Sequestration of the GSK3 enzyme in multivesicular endosomes is an essential step and is required for sustained WNT signalling. The decrease in active GSK3 causes newly synthesized β-catenin to accumulate and then be transported to the nucleus, where it activates gene transcription by TCF–LEF. APC/C, anaphase-promoting complex, also known as the cyclosome.

During WNT signalling, WNT ligands bind two co-receptors, Frizzled and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related 5 (LRP5) or LRP6, and this directs the localization of LRP6 into caveolin-containing vesicles for endocytosis. The cytoplasmic tail of LRP6 is phosphorylated by two enzymes, casein kinase 1 (CK1) and later GSK3, which are recruited together with axis inhibition protein (AXIN) from a cytosolic ‘destruction’ complex (consisting of APC/C (anaphase-promoting complex, also known as the cyclosome), AXIN, CK1 and GSK3), which normally degrades β-catenin. This triggers the polymerization of Dishevelled (DVL) and LRP6 on the plasma membrane and endocytosis of the WNT receptor complex13– 15. DVL, AXIN and β-catenin are required for this endocytosis12,13 and are all also GSK3 substrates; GSK3 localizes to these WNT-specific early endosomes, or ‘LRP6-signalosomes’, and this is important for regulating the phosphorylation of DVL, AXIN and β-catenin13.

The initial phosphorylation of LRP6 by GSK3 is required for the later sequestration of this enzyme in MVBs (FIG. 2). The phosphorylated LRP6 intracellular domain can also bind and inhibit GSK3 (REFS 16–19), and this interaction (which has an inhibition constant in the 10−5 M range) probably explains the transient decrease in GSK3 activity observed during the first 10 minutes of WNT addition20. However, the stabilization of β-catenin and the transcriptional activation of WNT target genes require persistent inhibition of GSK3 for several hours21. Sustained inhibition is achieved only when the ESCRT machinery sequesters sufficient amounts of GSK3 inside ILVs, protecting its many cytosolic substrates from phosphorylation12,22. Newly translated β-catenin protein is not phosphorylated by GSK3, so becomes stabilized and translocates into the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of WNT target genes.

Sequestration of GSK3 (or other inhibitory factors, such as AXIN) into MVBs must be very efficient. Catalytically inactive GSK3 is not localized inside MVBs upon WNT signalling, suggesting that this enzyme has to bind to its protein substrates in the cytosol in order to be sequestered into these specialized endosomes12. The signalosome consists of polymers of multiple proteins containing GSK3 phosphorylation sites, such as LRP6, Frizzled, AXIN, DVL and β-catenin13,14. Sustained WNT signalling cannot take place until these components are sequestered inside ILVs12. Once in ILVs, WNT receptor complexes may progress into lysosomes for degradation or fuse back to the endosomal membrane23 (FIG. 2), recycling GSK3 to the cytoplasm when the WNT signal is terminated (BOX 1). Thus, internalization, early signalosome formation and MVB sequestration are all essential steps in the endosomal trafficking of receptor complexes and canonical WNT signalling (FIG. 2).

WNT signalling regulates protein stability

GSK3 recognizes pre-phosphorylated residues in its many substrates, and it phosphorylates upstream clusters of Ser or Thr residues spaced four amino acids away24. Such highly phosphorylated stretches in proteins (called phosphodegrons) can become targets for recognition by E3 polyubiquitin ligases and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. So, when GSK3 is sequestered into MVBs in the presence of WNT, many cellular proteins that are protected from GSK3-mediated phosphorylation become stabilized12. However, the effects of the WNT signal on gene transcription are transduced specifically through the stabilization of β-catenin, which translocates into the nucleus, binds its cofactor T cell factor (TCF) and activates WNT–TCF target genes25,26.

WNT signalling requires the ESCRT machinery

Endocytosis is crucial for WNT signalling and can be blocked by inhibiting membrane internalization21,27. The formation of MVBs is also essential for WNT signal transduction: transcriptional WNT signals are blocked when ILV formation is inhibited by interfering with the ESCRT machinery components vacuolar protein sorting-associated 4 (VPS4) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-regulated Tyr kinase substrate (HRS), which promote membrane fission12. ILV invagination begins in early endosomes28 and continues in the late endosomal compartment.

HRS is a critical component of the ESCRT-0 machinery, which functions in the early steps of ILV formation in several contexts. In Drosophila melanogaster, HRS is required for the degradation of many growth factor receptors, such as those of HGF, Decapentaplegic (the D. melanogaster homologue of BMP), EGF and Notch29. HRS is phosphorylated at Tyr residues on activation of HGF receptor (HGFR) or EGFR, and this facilitates their degradation30. However, inhibition of other ESCRT components does not always result in the upregulation of growth factor signalling31–33, indicating that ESCRTs have multiple functions in signalling.

Interestingly, HRS levels are upregulated in many cancers. Moreover, small interfering RNA-mediated depletion of HRS in these tumours decreases malignancy, metastases34 and β-catenin levels, possibly implicating the WNT pathway in these oncogenic effects. This is in agreement with the observation that HRS depletion blocks WNT signal transduction12.

GSK3: degraded or recycled?

As GSK3 translocates into multivesicular endosomes upon WNT signalling, the levels of this enzyme might be expected to decrease after MVBs fuse with lysosomes. However, total cellular GSK3 levels do not change after WNT treatment12,21. So, one possibility is that only the active fraction of GSK3 is translocated into MVBs, and inactive fractions bound to GSK3 substrates remain unchanged. Another possibility is that the WNT-specific translocation of GSK3 into ILVs may be reversed by fusion back to endosomal membranes, returning GSK3 to the cytosol when the WNT signal ends (FIG. 2). Such ‘back-fusion’ would also make it possible for membrane lipid components to recycle back to the plasma membrane (BOX 1) and is supported by studies describing a pH-, lypobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA)- and ATP-dependent process in which ILVs ‘melt’ back into the outer membrane of MVBs and release their content into the cytoplasm23,35,36. In this model, multivesicular endosomes would provide a cellular compartment in which proteins could be held captive for as long as signalling persists and then released back to the cytosol upon signal termination. Whether WNT-containing MVBs are just lysosomal precursors or more-regulated signalling organelles will be important to resolve.

Signalling ‘insulation’ and crosstalk

The subcellular compartmentalization of GSK3 may be important for regulating crosstalk between pathways. GSK3-mediated phosphorylation events participate in multiple signalling pathways, such as those involving WNT, Hedgehog or BMP. In each case, these phosphorylation events lead to the polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of key transcriptional effectors, such as β-catenin, D. melanogaster cubitus interruptus (CI; GLI3 in vertebrates) or SMADs. The activity of GSK3 is also itself regulated by insulin signalling, through inhibitory phosphorylation events at Ser9 and Ser21 in GSK3β and GSK3α, respectively, which are triggered by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)–AKT (also known as PKB) pathway24. Given the wide range of GSK3 targets, mechanisms must exist to ‘insulate’ the multitude of signals received by the cell. The system should also be sufficiently flexible to allow for crosstalk between pathways, as occurs between the BMP and WNT signalling pathways, in which sequestration of GSK3 also prolongs the BMP signal37,38.

The ability of pathways to be insulated from each other could be explained by the existence of at least three different pools of GSK3: insulin–AKT-regulated, AXIN-associated and AXIN-independent39. Consistent with this, AKT regulates GSK3 by Ser phosphorylation upon insulin signalling and does not interfere with WNT-induced accumulation of β-catenin20. In this model, the AXIN-associated pool of GSK3 in the cytosol, which forms the β-catenin destruction complex, would be the only one that can be inhibited by WNT signalling. Free cytoplasmic GSK3 would still be available to phosphorylate the effectors of other signalling pathways. However, GSK3 mutants that are unable to bind AXIN do accumulate inside MVBs in response to WNT signalling, provided they are still catalytically active12. This suggests that GSK3 accumulates in endosomes not because all of it is AXIN-bound, but rather because it binds to its many phosphorylation substrates in the WNT receptor complex (such as LRP6, Frizzled, DVL, AXIN and β-catenin).

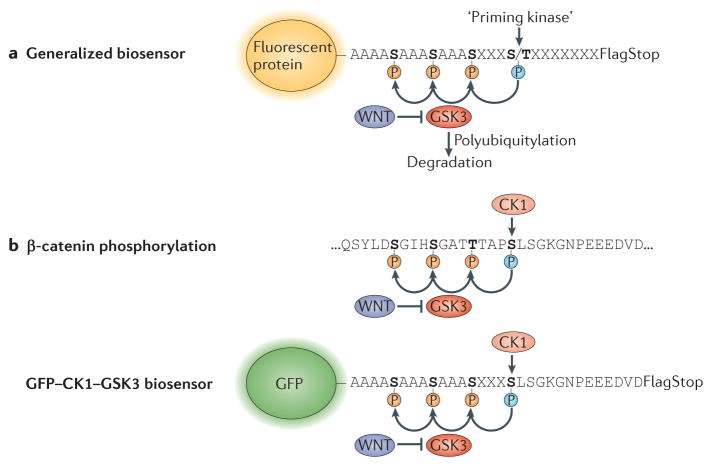

Insulation via ‘priming kinases’?

GSK3 phosphorylates many proteins24,40,41. Bioinformatic analyses show that 20% of all human proteins contain three or more potential GSK3 phosphorylation sites. Moreover, pulse-chase experiments show that WNT signalling, through GSK3 inhibition, significantly prolongs the half-life of many cellular proteins in addition to β-catenin12. In these putative GSK3 proteomic targets, the priming phosphate can be introduced by various kinases, such as CK1, CK2, MAPK, protein kinase A (PKA) and others. We propose that insulation of signalling pathways can be accomplished in part by regulation of the kinase that is used to prime a target for GSK3-mediated phosphorylation (FIG. 3). Other factors, such as the relative affinity of GSK3 for the various target proteins, will also be important.

Figure 3. Generation of protein half-life biosensors and their potential use in signalling integration studies.

a | A generic biosensor of intracellular glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) activity is shown. It consists of a fluorescent protein (green fluorescent protein (GFP) or red FP (RFP)) with a carboxy-terminal peptide containing phosphorylation sites. Three artificial GSK3 sites are placed in front of a ‘priming kinase’ site (which could correspond to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), casein kinase 1 (CK1), CK2, protein kinase A (PKA) or many others); further downstream, an epitope tag (flag; which is useful for biochemical analyses) and a stop codon complete the biosensor. The presence of GSK3 phosphorylation sites in the protein destabilizes it, forming a short phosphodegron that promotes polyubiquitylation by endogenous E3 ligases and its proteasomal degradation. b | Phosphorylation sites that promote degradation in human β-catenin and in the artificial GFP biosensor GFP–CK1–GSK3, derived from their sequences12. CK1 primes three phosphorylation events by GSK3, and the presence of such priming kinase phosphorylation sites may promote specificity in signalling responses, helping to ‘insulate’ different signalling pathways from one another.

This ‘priming kinase’ hypothesis can be tested experimentally by using fluorescent biosensors that are regulated by GSK3. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) biosensors have been used to test the requirements of GSK3 target regulation, and they have shown that targets are regulated by a priming phosphate and three GSK3 target sites. They also indicate that the levels of active GSK3 in cells are in fact decreased by WNT treatment12 (FIG. 3). Mutating the GSK3 target sites prevents the formation of the phosphodegron that is recognized by E3 polyubiquitin ligases, so that the artificial protein is no longer sensitive to WNT. These biosensors can also be used to test the priming kinase hypothesis by assessing the regulation of biosensors that differ only in the initial phosphorylation site (FIG. 3). These novel reagents are expected to be useful for studying how protein degradation triggered by growth factors is regulated.

A broader role for sequestration?

Many activated growth factor receptors traffic through multivesicular endosomes1. This raises the question of whether other signalling pathways might sequester cytosolic proteins as a means of regulating signalling.

One example may be NF-κB signalling, which is a key pathway in innate immunity. HRS is required for NF-κB signalling, reminiscent of its role in WNT signalling. An RNA interference (RNAi) screen also revealed a positive role for MVB formation in D. melanogaster NF-κB (known as Toll) signalling42. RNAi-mediated depletion of Myopic or HRS, two critical components of the ESCRT-0 complex, prevented the degradation of the D. melanogaster Inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) homologue Cactus, which normally inhibits the translocation of Toll into the nucleus. These findings show that endocytic trafficking and MVB formation are required to activate, rather than to downregulate, the Toll signalling pathway, and it is possible that this requires sequestration of Cactus or another negative regulator in MVBs.

Sequestration of SRC may also be relevant for signalling downstream of the β2 adrenergic GPCR. Receptor activation by its ligand triggers the relocalization of SRC Tyr kinase into cytoplasmic vesicle-like structures43. The adaptor protein β-arrestin mediates binding of SRC to the receptor, targeting the complex for endocytosis. In addition, phosphorylation of dynamin Tyr residues mediated by SRC is essential for its endocytosis44. Thus, SRC activity is required for the endocytosis of its associated receptor, which may lead to its sequestration in MVBs and the depletion of its cytoplasmic activity. Similarly to SRC, GSK3 is also required for its own endocytosis, as it must phosphorylate the cytoplasmic tail of the LRP6 receptor for WNT receptor complexes to be assembled and internalized13,14. Intriguingly, the β2 adrenergic receptor requires HRS for its resensitization at the membrane, suggesting that this GPCR is recycled back to the plasma membrane45. Whether SRC does indeed accumulate in MVBs, and what cytosolic targets this may afford protection for, remains to be seen.

The JAK–STAT pathway may also require endosomal trafficking. There have been mixed reports as to whether inhibition of HRS in D. melanogaster blocks46 or promotes47 the nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor STAT. Further studies will be needed to assess the possible role of MVB sequestration in this pathway.

A positive function of MVBs has been documented for Notch signalling48. Endocytosis of Notch upon ligand binding leads to its relocalization to a multivesicular endosomal compartment. Degradation of the Notch extracellular domain by lysosomal enzymes facilitates cleavage by the intra-membrane protease presenilin, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) into the cytoplasm; the NICD then translocates into the nucleus, where it helps to initiate transcription49. Two possibilities have been proposed for Delta–Notch interactions in multivesicular endosomes50. Notch might remain in the outer endosomal membrane bound to Delta located in ILVs; Delta binding would release the NICD into the cytosol for its subsequent translocation into the nucleus. Alternatively, the Notch receptor could be incorporated in ILVs with Delta remaining on the outer endosomal membrane; in this model, after digestion by lysosomal enzymes and presenilins, the still-intact NICD would be delivered to the cytosol by back-fusion of ILVs to the outer endosomal membrane50.

In summary, the ESCRT machinery and MVBs seem to have two principal roles in growth factor signalling. First, as has long been known, endosomal trafficking to lysosomes negatively regulates signalling downstream of many growth factors by degrading their receptors. Second, ESCRT-dependent removal of cytosolic inhibitory components, such as GSK3 in the WNT pathway and IκB in the NF-κB pathway, is starting to emerge as a positive function of multivesicular endosomes in signalling.

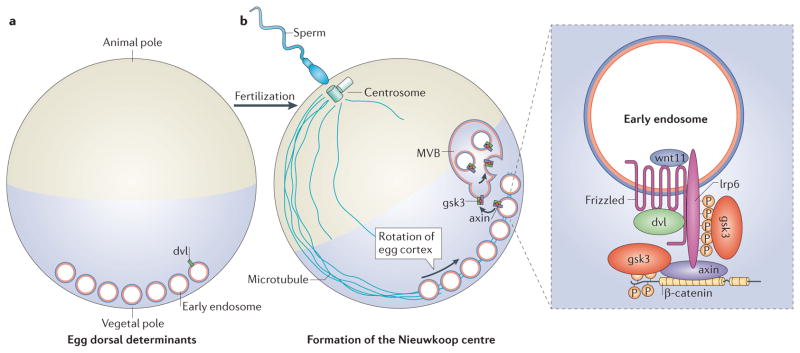

MVBs in embryonic axis formation

It is possible that the regulation of signalling pathways through factor sequestration into MVBs is important in diverse physiological contexts. Here, we propose that gsk3 sequestration during wnt signalling may be important for the formation of the dorsal axis during Xenopus laevis development. The X. laevis egg contains unknown ‘maternal determinants’ at its vegetal pole in its bottom half. After fertilization, these move along cortical microtubules towards the future dorsal side of the embryo51,52 (FIG. 4). The future embryonic axis is then formed where the vegetal cytoplasm comes in contact with the animal cytoplasm of the top half of the egg (FIG. 4). Conjoined twins form when a new such interface is induced experimentally53,54, and twinning can also be induced by microinjection of wnt mRNA into the ventral side of the early embryo55. Use of this micro-injection assay has shown that an endogenous maternal wnt signal acts at the first step of embryonic differentiation and mimics the dorsal determinant, activating the formation of the Nieuwkoop centre in the blastula. This centre in turn induces the Spemann organizer at the gastrula stage, giving rise to the embryonic axis56. The endogenous maternal wnt signal has an intriguing property: it is completely resistant to inhibition by microinjection of mRNA encoding potent extracellular wnt antagonists, such as Dickkopf homologue 1 (dkk1) and secreted Frizzled-related proteins (sfrps)), whereas microinjected wnt mRNA or endogenous wnt8 at the gastrula stage are readily inhibited by these antagonists57.

Figure 4. Hypothesis: the dorsal determinants of the Xenopus laevis egg may be endosomal components.

The vegetal pole of the frog egg contains ‘maternal determinants’ of unknown composition. We propose here that they may correspond to wnt-containing early endosomes that become incorporated into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) on the dorsal side of the zygote. This would sequester glycogen synthase kinase 3 (gsk3) and axis inhibition protein (axin) inside MVBs, triggering the earliest wnt signal in vertebrate embryonic differentiation, which induces the Nieuwkoop signalling centre. a | In the unfertilized egg, membrane vesicles are observed in the vegetal pole61. b | The sperm brings with it the centriole, giving rise to a centrosome that organizes a cortical network of microtubules. Early endosomes from the vegetal pole are transported along microtubules to the dorsal side, which forms opposite the sperm entry point. The new embryonic axis forms where vegetal material and animal cytoplasm mix55. Cortical microtubules cause a rotation of the egg cortex towards the sperm entry point, displacing the superficial pigment of the egg53. This forms a lighter ‘dorsal crescent’ that marks the dorsal side. One possibility is that maternal wnt is secreted by the oocyte and internalized into early endosomes at the vegetal pole. Upon fertilization, the formation of MVBs at the dorsal side might promote gsk3 sequestration and thereby allow persistent wnt signalling to promote axis formation. dvl, dishevelled; lrp6, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related 6.

One possibility, then, is that gsk3 sequestration regulates wnt signalling during dorsal axis determination. Maternal wnt may constitute the dorsal determinant, and it may be secreted by oocytes and then internalized into the lumen of early endosomal vesicles (FIG. 2), attached to wnt receptor complexes. After being transported to the dorsal side of the fertilized egg, these signalosomes would mature into MVBs, facilitated by cytoplasmic components from the animal pole. Once ILVs form, this would cause the sequestration of gsk3, axin and other proteins into MVBs in the dorsal crescent of the egg (FIG. 4). This would then lead to stabilization of β-catenin and the transcription of genes that determine the formation of the Nieuwkoop centre.

Multiple lines of evidence are consistent with this theory. First, oocytes are extremely active in endocytosis, particularly in the vegetal region, as they take up their yolk proteins (which are synthesized in the liver) from the maternal circulation58. Second, ultrastructural studies have shown that a main difference between X. laevis oocytes and somatic cells is the presence of ‘nests’ of uniformly sized vesicles (called Balinsky bodies, after their discoverer) that disperse below the egg cortex after fertilization59; we suggest that these vesicles might correspond to early signalosomes containing internalized wnt. Third, movement of dvl–GFP particles along microtubule tracks has been reported in activated oocytes60. Fourth, X. laevis wnt11 is a good candidate for the maternal wnt signal, as its mRNA is localized vegetally in the oocyte (where it presumably acts in an auto-crine manner) and is required during late oogenesis for axis formation in the embryo61. Interestingly, MVBs were first discovered in electron micrographs of the rat egg, in which they become very abundant after fertilization62. Moreover, this model would also explain why dkk1 or sfrps cannot inhibit the maternal wnt signal in the early embryo: as wnt would already be safely ensconced inside early endosomes at the oocyte stage, it would not be accessible to extracellular inhibitors microinjected after fertilization. Further investigation of whether gsk3 sequestration may be physiologically relevant during egg development, or in other developmental contexts, is certainly warranted.

Conclusions and perspectives

Endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of activated receptors is widely used as a mechanism of signal downregulation. Although, in some cases, early signalling endosomes can maintain the signal until receptors are engulfed in the ILVs of multivesicular endosomes, the localization to MVBs has always been associated with negative control of signalling. Thus, the recently discovered sequestration of inhibitory factors inside MVBs as a trigger for growth factor signalling provides a new perspective on the intersection between endocytosis and cell signalling. So far, this sequestration mechanism has only been demonstrated to function during canonical WNT signalling12. However, there is good evidence that the ILV-forming machinery is also required for NF-κB signalling by the D. melanogaster innate immunity Toll signalling pathway42. Whether other signalling pathways also require cytosolic components to be sequestered into MVBs after growth factor activation remains an open and interesting question. Such a mechanism would allow proteins to be selectively depleted from the cytosol in response to a specific growth factor that the cell receives from the extracellular medium.

The role of MVB formation has been difficult to assess, as the existing HRS mutation gives differing results depending on experimental context, and advancing the field may require the characterization of new ESCRT mutants and RNAi reagents in D. melanogaster. In other systems, such as X. laevis and cultured mammalian cells, improved reagents that interfere with the ESCRT machinery will facilitate the use of transcriptional reporter gene assays for various pathways and allow rapid screening for whether multivesicular endosomes are required for signalling. In addition, the finding that GSK3 sequestration in MVBs is an important element in the regulation of global cellular protein turnover12 should lead the field in new directions.

As the endosomal–lysosomal pathway is required for WNT signalling, its role in cancer will need to be re-examined in this light. HRS overexpression causes increased malignancy and metastases in many solid tumours, accompanied by an increase of β-catenin levels34. Other members of the ESCRT machinery can also either suppress or promote tumorigenesis, including tumour susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101; the binding partner of HRS)63–65, VPS25 (REFS 66,67) and VPS24 (REFS 68,69). These opposing effects of ESCRT components in cancer suggest complex interactions that are incompletely understood but which might be approached productively by studying their effects on growth factor signalling. Finally, it will be important to assess the roles that this regulatory mechanism may have during development. For example, GSK3 sequestration in MVBs offers a novel hypothesis for the molecular nature of the elusive dorsal determinants that transduce the earliest wnt signal during X. laevis development. In conclusion, it seems that multivesicular endosomes are key signalling organelles that can promote specificity through subcellular compartmentalization of signalling factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory for comments on the manuscript, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for supporting R.D. and the US National Institutes of Health for support. E.M.D.R. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Edward M. De Robertis’s homepage:

http://www.hhmi.ucla.edu/derobertis/index.html

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;12:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piper RC, Katzmann DJ. Biogenesis and function of multivesicular bodies. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:519–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKanna JA, Haigler HT, Cohen S. Hormone receptor topology and dynamics: morphological analysis using ferritin-labeled epidermal growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5689–5693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurley JH. ESCRT complexes and the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raiborg C, Stenmark H. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;458:445–452. doi: 10.1038/nature07961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Regalado A, et al. G protein-coupled receptor-promoted trafficking of Gβ1γ2 leads to AKT activation at endosomes via a mechanism mediated by Gβ1γ2-Rab11a interaction. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4188–4200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimes ML, et al. Endocytosis of activated TrkA: evidence that nerve growth factor induces formation of signaling endosomes. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7950–7964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07950.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson FL, et al. Neurotrophins use the Erk5 pathway to mediate a retrograde survival response. Nature Neurosci. 2001;4:981–988. doi: 10.1038/nn720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukazaki T, Chiang TA, Davison AF, Attisano L, Wrana JL. SARA, a FYVE domain protein that recruits Smad2 to the TGFβ receptor. Cell. 1998;95:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes S, Chawla A, Corvera S. TGFβ receptor internalization into EEA1-enriched early endosomes: role in signaling to Smad2. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1239–1249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taelman VF, et al. Wnt signaling requires sequestration of glycogen synthase kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell. 2010;143:1136–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilic J, et al. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes Dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2007;316:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1137065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng X, et al. Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via Frizzled, Dishevelled and Axin functions. Development. 2008;135:367–375. doi: 10.1242/dev.013540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalfe C, Mendoza-Topaz C, Mieszczanek J, Bienz M. Stability elements in the LRP6 cytoplasmic tail confer efficient signalling upon DIX-dependent polymerization. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1588–1599. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mi K, Dolan PJ, Johnson GVW. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 interacts with glycogen synthase kinase 3 and attenuates activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4787–4794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cselenyi CS, et al. LRP6 transduces a canonical Wnt signal independently of Axin degradation by inhibiting GSK3’s phosphorylation of β-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8032–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803025105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piao S, et al. Direct inhibition of GSK3β by the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of LRP6 in Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu G, Huang H, Garcia Abreu J, He X. Inhibition of GSK3 phosphorylation of β-catenin via phosphorylated PPPSPXS motifs of Wnt coreceptor LRP6. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding VW, Chen RH, McCormick F. Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β by insulin and Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32475–32481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blitzer JT, Nusse R. A critical role for endocytosis in Wnt signaling. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platta HW, Stenmark H. Endocytosis and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleijmeer M, et al. Reorganization of multivesicular bodies regulates MHC class II antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:53–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–776. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto H, Komekado H, Kikuchi A. Caveolin is necessary for Wnt-3a-dependent internalization of LRP6 and accumulation of β-catenin. Dev Cell. 2006;11:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wegener CS, et al. Ultrastructural characterization of giant endosomes induced by GTPase-deficient Rab5. Histochem Cell Biol. 2010;133:41–55. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jékely G, Rørth P. Hrs mediates downregulation of multiple signalling receptors in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern KA, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor fate is controlled by Hrs tyrosine phosphorylation sites that regulate Hrs degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:888–898. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02356-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malerød L, Stuffers S, Brech A, Stenmark H. Vps22/EAP30 in ESCRT-II mediates endosomal sorting of growth factor and chemokine receptors destined for lysosomal degradation. Traffic. 2007;8:1617–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bache KG, et al. The ESCRT-III subunit hVps24 is required for degradation but not silencing of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2513–2523. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chanut-Delalande H, et al. The Hrs/Stam complex acts as a positive and negative regulator of RTK signaling during Drosophila development. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toyoshima M, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by depletion of vesicular sorting protein Hrs: its regulatory role on E-cadherin and β-catenin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5162–5171. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falguières T, Luyet PP, Gruenberg J. Molecular assemblies and membrane domains in multivesicular endosome dynamics. J Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1567–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Bartheld CS, Altick AL. Multivesicular bodies in neurons: distribution, protein content, and trafficking functions. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:313–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuentealba LC, et al. Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell. 2007;131:980–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eivers E, Demagny H, Choi RH, De Robertis EM. A molecular competition between wingless and BMP signaling controlled by mad phosphorylations. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra68. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jope RS, Johnson GV. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim NG, Xu C, Gumbiner BM. Identification of targets of the Wnt pathway destruction complex in addition to β-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5165–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810185106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang HR, Chen ZJ, Kunes S, Chang GD, Maniatis T. Endocytic pathway is required for Drosophila Toll innate immune signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8322–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luttrell LM, et al. β-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahn S, Maudsley S, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Daaka Y. Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of dynamin is required for β2-adrenergic receptor internalization and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1185–1188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanyaloglu AC, McCullagh E, von Zastrow M. Essential role of Hrs in a recycling mechanism mediating functional resensitization of cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:2265–2283. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devergne O, Ghiglione C, Noselli S. The endocytic control of JAK/STAT signalling in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3457–3464. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vidal OM, Stec W, Bausek N, Smythe E, Zeidler MP. Negative regulation of Drosophila JAK–STAT signalling by endocytic trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3457–3466. doi: 10.1242/jcs.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coumailleau F, Fürthauer M, Knoblich JA, González-Gaitán M. Directional Delta and Notch trafficking in Sara endosomes during asymmetric cell division. Nature. 2009;458:1051–1055. doi: 10.1038/nature07854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilkin M, et al. Drosophila HOPS and AP-3 complex genes are required for a Deltex-regulated activation of notch in the endosomal trafficking pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;15:762–772. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fürthauer M, González-Gaitán M. Endocytic regulation of notch signalling during development. Traffic. 2009;10:792–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rowning BA, et al. Microtubule-mediated transport of organelles and localization of β-catenin to the future dorsal side of Xenopus eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1224–1229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver C, Kimelman D. Move it or lose it: axis specification in Xenopus. Development. 2004;131:3491–3499. doi: 10.1242/dev.01284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nieuwkoop PD. Origin and establishment of embryonic polar axes in amphibian development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1977;11:115–132. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60744-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Black SD, Gerhart JC. High-frequency twinning of Xenopus laevis embryos from eggs centrifuged before first cleavage. Dev Biol. 1986;116:228–240. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMahon AP, Moon RT. Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 in Xenopus embryos leads to duplication of the embryonic axis. Cell. 1989;58:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Robertis EM. Spemann’s organizer and selfregulation in amphibian embryos. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:296–302. doi: 10.1038/nrm1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim SH, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell. 1997;88:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Opresko L, Wiley HS, Wallace RA. Differential postendocytotic compartmentation in Xenopus oocytes is mediated by a specifically bound ligand. Cell. 1980;22:47–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balinsky BI. Changes in the ultrastructure of amphibian eggs following fertilization. Acta Embryol Morphol Exp. 1966;9:132–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller JR, et al. Establishment of the dorsal–ventral axis in Xenopus embryos coincides with the dorsal enrichment of Dishevelled that is dependent on cortical rotation. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:427–437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tao Q, et al. Maternal Wnt11 activates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway required for axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 2005;120:857–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sotelo JR, Porter KR. An electron microscope study of the rat ovum. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1959;5:327–342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.5.2.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young TW, et al. Up-regulation of tumor susceptibility gene 101 conveys poor prognosis through suppression of p21 expression in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3848–3854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oh KB, Stanton MJ, West WW, Todd GL, Wagner KU. Tsg101 is upregulated in a subset of invasive human breast cancers and its targeted overexpression in transgenic mice reveals weak oncogenic properties for mammary cancer initiation. Oncogene. 2007;26:5950–5959. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu RT, et al. Overexpression of tumor susceptibility gene TSG101 in human papillary thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:4830–4837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaccari T, Bilder D. The Drosophila tumor suppressor vps25 prevents nonautonomous overproliferation by regulating notch trafficking. Dev Cell. 2005;9:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thompson BJ, et al. Tumor suppressor properties of the ESCRT-II complex component Vps25 in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J, Belogortseva N, Porter D, Park M. Chmp1A functions as a novel tumor suppressor gene in human embryonic kidney and ductal pancreatic tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2886–2893. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson EM, Oh Y, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG. Interaction of IGF-binding protein-related protein 1 with a novel protein, neuroendocrine differentiation factor, results in neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4504–4511. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Babst M. A protein’s final ESCRT. Traffic. 2005;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babst M, Wendland B, Estepa EJ, Emr SD. The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J. 1998;17:2982–2993. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernandez-Borja, et al. Multivesicular body morphogenesis requires phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase activity. Curr Biol. 1999;9:55–58. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stoorvogel W, Strous GJ, Geuze HJ, Oorschot V, Schwartz AL. Late endosomes derive from early endosomes by maturation. Cell. 1991;65:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90459-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohashi M, Miwako I, Yamamoto A, Nagayama K. Arrested maturing multivesicular endosomes observed in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant, LEX2, isolated by repeated flow-cytometric cell sorting. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2187–2205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Woodman PG, Futter CE. Multivesicular bodies: co-ordinated progression to maturity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raiborg C, Rusten TE, Stenmark H. Protein sorting into multivesicular endosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:446–455. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nrm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:329–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Denzer K, Kleijmeer MJ, Heijnen HF, Stoorvogel W, Geuze HJ. Exosome: from internal vesicle of the multivesicular body to intercellular signaling device. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3365–3374. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Février B, Raposo G. Exosomes: endosomal-derived vesicles shipping extracellular messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murk JL, Stoorvogel W, Kleijmeer MJ, Geuze HJ. The plasticity of multivesicular bodies and the regulation of antigen presentation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sahu R, et al. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell. 2011;20:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cruciat CM, et al. Requirement of prorenin receptor and vacuolar H+-ATPase-mediated acidification for Wnt signaling. Science. 2010;327:459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.1179802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]