Abstract

Purpose.

Achieving good vision in infants born with a unilateral cataract is believed to require early surgery and consistent occlusion of the fellow eye. This article examines the relationship between adherence to patching and grating acuity.

Methods.

Data came from the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study, a randomized clinical trial of treatment for unilateral congenital cataract. Infants were either left aphakic (n = 53) or had an intraocular lens implanted (n = 55). Patching was prescribed 1 hour per day per month of age until 8 months of age and 50% of waking hours thereafter. Adherence was measured as the mean percentage of prescribed patching reported in a 7-day diary completed 2 months after surgery, and 48-hour recall interviews conducted 3 and 6 months after surgery. Grating visual acuity was measured within 1 month of the infant's first birthday (n = 108) using Teller Acuity Cards by a tester masked to treatment. Nonparametric correlations were used to examine the relationship with grating acuity.

Results.

On average, caregivers reported patching 84.3% (SD = 31.2%) of prescribed time and adherence did not differ by treatment (t = −1.40, df = 106, p = 0.16). Adherence was associated with grating acuity (rSpearman = −0.27, p < 0.01), but more so among pseudophakic (rSpearman = −0.41, p < 0.01) than aphakic infants (rSpearman = −0.10, p = 0.49).

Conclusions.

This study empirically has shown that adherence to patching during the first 6 months after surgery is associated with better grating visual acuity at 12 months of age after treatment for unilateral cataract and that implanting an intraocular lens is not associated with adherence. (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00212134.)

This article evaluates the relationship between adherence to patching within 6 months of cataract extraction and grating visual acuity at 12 months of age in infants born with a unilateral cataract.

Introduction

Infants born with visually significant unilateral congenital cataracts often have poor vision outcomes. Previous reports suggest that achieving a good vision outcome requires early surgical removal of the cataract, consistent optical correction of the aphakia or residual refractive errors, and good adherence to a regimen of occlusion of the fellow eye.1–5

Chak and colleagues report that poor adherence to occlusion is the factor most strongly associated with poor visual acuity in children following treatment for unilateral cataract.6 However, others note that good visual acuity is achievable among infants with good adherence to patching in the first year of life, but lower levels of adherence thereafter.7 It is likely that good visual acuity depends on adherence to occlusion therapy, but that adherence also depends on visual acuity because patching becomes more difficult in children with poorer visual acuity.5 The impact of good adherence to occlusion therapy on vision outcome is, therefore, likely to be somewhat difficult to disentangle from the impact of visual acuity on adherence to occlusion.

The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) is a multi-center, randomized, controlled clinical trial of treatment for unilateral congenital cataract in infants between 1 and 7 months of age sponsored by the National Eye Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The objective of the study is to compare the vision outcome in children with a unilateral congenital cataract if an intraocular lens (IOL) is implanted at the time of cataract extraction with the vision outcome in children who were left aphakic.8 Earlier reports from the IATS suggest that at 12 months of age there is wide variation in the vision outcome of children treated for unilateral congenital cataract, but that the treatment choice is not significantly associated with visual acuity.9 Further, the authors of this article have shown that caregivers generally report good adherence to patching 3 months after surgery, and that adherence to occlusion therapy varies with sociodemographic factors and parenting stress. These authors also noted that adherence to occlusion is not significantly related to treatment modality 3 months after surgery.10

It is important to understand the role of occlusion therapy in the development of visual acuity in this population. The purpose of this article is to examine the inter-relationships between treatment, adherence to patching within the first 6 months after surgery, and grating visual acuity measured at 12 months of age. The focus was on adherence to occlusion therapy within 6 months of surgery as this was prior to the first objective assessment of visual acuity for nearly all participants and was within the period during which it was anticipated that adherence to patching was least likely to be affected by differences in visual acuity.

Methods

The IATS is a multi-center, randomized controlled clinical trial comparing IOL to contact lens treatment after cataract surgery performed at 1 to 6 months of age in infants with a unilateral congenital cataract. None of the participants were lost to follow-up during the first 12 months after surgery and all participants had their vision measured at approximately 12 months of age by a tester masked to treatment assignment. The details of the study methodology, the baseline clinical characteristics of the participants, and visual acuity at 12 months of age have been previously published.8,9 Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all participants after they had been told about the study's requirements and possible risks and benefits. All subjects were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Follow-Up Examinations and Grating Visual Acuity Assessment

Follow-up examinations were performed by an IATS certified investigator at 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months after cataract surgery. Subsequent follow-up examinations were obtained at 3-month intervals (± 2 weeks). The investigator performed a standard clinical examination, checking the appropriateness of the optical correction and monitoring for adverse events. All of the participants underwent an examination-under-anesthesia (EUA) 2 to 4 weeks prior to the grating visual acuity assessment. The participants' optical correction was updated between the EUA and the grating acuity assessment.

Monocular grating acuity was measured at approximately 12 months of age (median = 255 days with inter-quartile range = 345 to 366 days) using a pediatric visual acuity test (Teller Acuity Cards; Stereo Optical, Chicago, IL) administered by a traveling examiner who was masked to treatment. Three participants had visual acuity measurements obtained more than 30 days after the first birthday (at days 413, 535, and 568) and none had the visual acuity assessment completed more than 30 days before the first birthday. Vision in the aphakic/pseudophakic eye was tested first. The standard testing distance was 55 cm measured from the screen to the participants' eyes. Those with poor visual acuity were tested at progressively nearer distances (e.g., 38, 19, 9.5 cm) or using the low vision card to determine the presence or absence of some pattern vision. Evaluations of Light Perception (LP) only or No Light Perception (NLP) vision abilities were performed following standard clinical protocols.

In addition to an ordinal measure of grating acuity, visual acuity was categorized as within normal limits (WNL) or poor. Visual acuity WNL was defined as a measured grating acuity that was within 95% of predictive limits for 12-month-old infants as described by Mayer.11

Prescribed Patching

Patching was prescribed for all participants throughout the first year of life. Starting the second week after cataract surgery, caregivers were instructed to have the infant wear an adhesive occlusive patch over the fellow eye 1 hour per day per month of age until the infant was 8 months old. Thereafter, patching was prescribed for half of waking hours either by patching full time every other day or by daily patching one half of the time the infant was awake.

Assessment of Adherence to Patching Regimen

Adherence to the patching regimen was assessed by staff from the centralized Data Coordinating Center (DCC). Two months after surgery, caregivers were mailed a 7-day prospective patching diary. Instructions for completing this diary were provided to the caregiver by staff at a clinic visit 1 month after surgery, and additional written instructions were mailed with the diary. The diary requested specific information about the times the infant was asleep, the times spectacles or contact lenses were worn, and the times that the fellow eye was occluded. Starting 3 months after surgery, a staff member from the DCC completed a 48-hour recall interview every 3 months. This semistructured interview collected the same information as the diary. The interviews were conducted by one of three trained interviewers (one English-speaking, one Spanish-speaking, and one Portuguese-speaking) with the caregiver interviewed by the same person on each occasion. More than 95% of the interviews were conducted in English by a single interviewer.

The current analyses focused on adherence during the first 6 months after surgery. Data collected 9 months after surgery was not included because more than 40% of IATS participants had undergone the visual acuity assessment prior to the 9-month adherence interview. For purposes of these analyses, adherence to prescribed occlusion therapy was defined as the mean percentage of prescribed patching that was reported at the first three adherence assessments: the 7-day diary completed 2 months after surgery, and the telephone interviews completed 3 and 6 months after surgery. Per discussions with the study's Data Safety Monitoring Board, good adherence was defined as reporting at least 75% of prescribed patching. This was summarized over the first 6 months by documenting the frequency of assessments (none, some, or all) at which the caregiver reported achieving good adherence.

Covariates

The impact of a variety of covariates on the observed associations was considered. These covariates were age at surgery (28 to 48 days, 49 days to 3 months or fewer plus 0 days, and 3 months or greater plus 1 day) and the presence of adverse events such as glaucoma, pupillary membrane extending into the visual axis, lens reproliferation, or requirement of additional surgery.12 These were considered as possible confounders because of the likely associations with both visual acuity and adherence. An additional consideration was the possibility that the availability of private insurance and parenting stress measured at 3 months post-surgery using the Parenting Stress Index13 might modify the association between adherence and visual acuity because earlier analyses indicated that they were associated with adherence.10

Analytic Methods

All analyses were conducted using statistical packages (SAS 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) (SPSS 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) . The analyses focused on three questions. The first question was whether or not the type of surgery (absence or presence of IOL implantation) was associated with adherence to patching. Student's t-tests and repeated measures analyses of variance were used to assess whether type of surgery was related to the mean amount of patching, and chi-square tests of independence were used to consider whether the type of surgery was related to the number of assessments on which good patching was reported.

The second question was whether or not the percentage of prescribed patching was associated with grating visual acuity measured at 12 months of age . These analyses were performed using nonparametric tests (Spearman rank correlation coefficients, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Kruskall-Wallis and Jonckheere-Terpstra tests for ordered alternatives) since the markedly skewed distribution of grating visual acuities for IATS participants precluded parametric analyses. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test was used to examine the hypothesis that infants whose caregivers reported achieving at least 75% of the prescribed patching at all adherence assessments would have better visual acuity than those whose caregivers reported achieving such patching on some of these assessments, and the latter group would have better visual acuity than those whose caregivers never reported achieving this level of adherence. Fischer's z transformation under the null hypothesis was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals for the Spearman's correlation coefficients Logistic regression was used to determine if the number of times a caregiver reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching was associated with achieving a visual acuity that was within normal limits after controlling for potentially important confounders (i.e., treatment, age at surgery, and complications).

The third question was whether or not treatment group was associated with visual acuity within groups defined by adherence to prescribed patching and after controlling for adherence and other potential confounders.

Results

Study Population

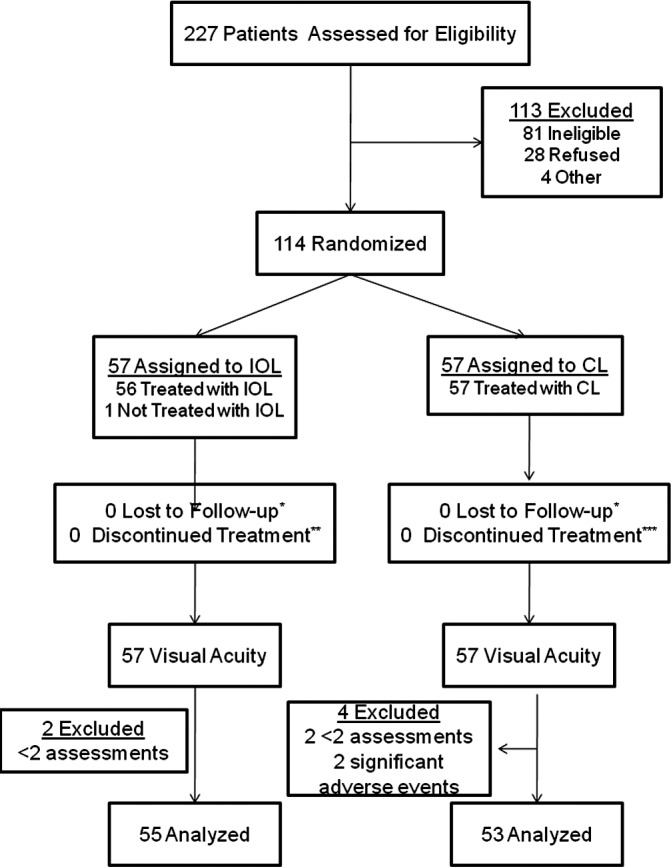

One-hundred fourteen participants were enrolled in IATS with 57 randomized to each treatment group. As noted in previous publications, one of the 57 participants randomized to receive an IOL was left aphakic because of clinical concerns about implanting an IOL. However, this participant was analyzed as part of the IOL arm. Two participants were excluded who had significant adverse events including retinal detachment that resulted in poor vision outcomes that would be unrelated to patching. One of these participants developed ocular inflammation, total hyphema, glaucoma, retinal detachment, and phthisis; the other participant had retinal detachment following retained cortex, inflammation, and endophthalmitis. Both of these participants had been randomized to receive contact lens treatment. Other participants with adverse events and/or complications were left in the sample because the extent to which these events directly impacted visual acuity was not clear. Four additional participants were excluded who had fewer than two measures of adherence (two randomized to IOL and two to CL) obtained prior to the assessment of grating visual acuity at 12 months of age. Thus, for this analysis, the sample included 108 children: 55 randomized to receive an IOL and 53 randomized to remain aphakic (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. .

Flow diagram depicting inclusion of subjects in the IATS and the current analysis.

Assessment of Adherence

Greater than 80% of participants provided data at each time point (Table 1). Ninety-eight (90.7%) caregivers returned the 7-day diary that was mailed 2 months after surgery. The proportion of caregivers who completed 48-hour interviews at 3 and 6 months after surgery was even higher (n = 106, 98.1% at both 3 and 6 months). However, data were not included from the 6-month adherence interview from 14 caregivers for whom the 6-month adherence interview was conducted after the visual acuity assessment visit at 12 months of age. The proportion completing each assessment did not differ by treatment group.

Table 1. .

Completion of Adherence Assessments among IATS Participants by Time Since Surgery

|

Time Since Surgery (Months) |

Method |

Randomized to Receive IOL N = 55 |

Randomized to Contact Lens N = 53 |

||||

|

Completed before Visual Acuity |

Completed after Visual Acuity |

Not Completed |

Completed before Visual Acuity |

Completed after Visual Acuity |

Not Completed |

||

| 2 | Diary | 49 (89.1%) | 0 | 6 | 49 (92.5%) | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | Interview | 54 (98.2%) | 0 | 1 | 52 (96.3%) | 0 | 2 |

| 6 | Interview | 46 (83.6%) | 8 | 1 | 45 (86.5%) | 6 | 1 |

Overall, caregivers reported achieving the majority of patching that was prescribed by clinicians. On average, caregivers reported patching the infants 84.3% (SD = 31.2%) of prescribed time, but the amount of patching varied widely from a low of 6% to a high of 174% . More than one third of caregivers reported patching the infants at least 75% of the prescribed time on each adherence assessment; while fewer than one in five reported achieving less than 75% of prescribed time on each assessment.

Three quarters of caregivers provided three assessments of adherence within 6 months of cataract extraction. Treatment was not associated with the number of assessments (two or three) available for analysis (χ2 = 0.58, df = 1, p = 0.37), or the frequency (none, some, or all) of assessments on which a caregiver reported patching at least 75% of the prescribed time (χ2 = 1.57 df = 2, p = 0.46. The 27 participants with two assessments had poorer vision than those who completed all three (p = 0.04).

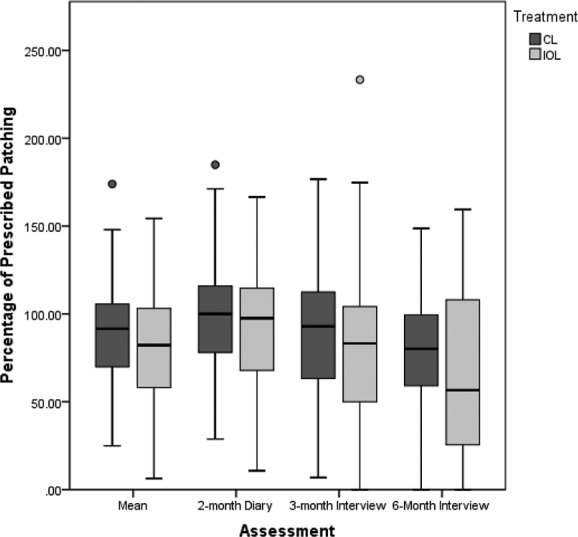

Relationship between Treatment and Adherence

The average percentage of prescribed patching reported by caregivers of participants receiving an IOL was somewhat lower than that reported by caregivers of aphakic infants. However, these differences were not statistically significant using either t-tests (t = −1.410, df = 106, p = 0.16 for the overall mean; t = −0.895, df = 96, p = 0.556 two months after surgery; t = −0.856, df = 104, p = 0.699 three months after surgery; t = −1.701, df = 105, p = 0.76 six months after surgery) or repeated measures ANOVA (F = 2.017, p = 0.159) (Fig. 2). The proportion of caregivers who reported patching at least 75% of prescribed time on all, some, or none of the assessments was also similar in the two treatment groups (χ2 = 2.67, df = 2, p = 0.26).

Figure 2. .

Percentage of prescribed patching by months after surgery and treatment among IATS participants.

Association between Adherence and logMAR Grating Visual Acuity

Infants whose caregivers reported better adherence to patching within the first year of life tended to have better logMAR grating visual acuity than infants whose caregivers reported less patching. The mean percentage of prescribed patching 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery was significantly correlated with logMAR grating acuity (rSpearman = −0.26, p < 0.01) (Table 2), as was adherence reported 2 (rSpearman = −0.23, p = 0.02) and 6 (rSpearman = −0.27, p < 0.01) months after surgery. The association between adherence reported 3 months after surgery and grating visual acuity was not statistically significant (rSpearman = −0.13, p = 0.19) but was in the same direction. The overall association between grating visual acuity and reported adherence within subgroups defined by covariates rarely achieved statistical significance, with the exceptions noted below. In addition, these correlations within subgroups were in the same direction and tended to be similar in magnitude to the overall association between grating visual acuity and reported adherence (Table 2). The association was statistically significant among participants with an adverse event (rSpearman = −0.35) but was not observed among participants who did not experience an adverse event (rSpearman = −0.10). The association varied systematically by age. No association was observed among participants in whom the cataract was removed at the earliest age (rSpearman = −0.03), but there was an association among those who were between 3 and 7 months of age at surgery (rSpearman = −0.26).

Table 2. .

Spearman's Correlation Coefficient (and 95% CI) between Reported Adherence to Prescribed Occlusion Therapy at 2, 3, and 6 Months after Surgery and Visual Acuity

|

Overall |

|||

|

N |

rSpearman |

95% CI |

|

| Overall | 108 | −0.26 | (−0.43,−0.08) |

| Treatment | |||

| IOL | 55 | −0.41 | (−0.61,−0.16) |

| CL | 53 | −0.03 | (−0.30,0.24) |

| Age at surgery | |||

| 28–48 days | 47 | −0.09 | (−0.37,0.20) |

| 49 days–3.0 months | 30 | −0.21 | (−0.52,0.17) |

| >3.1 months | 31 | −0.37 | (−0.64,−0.01) |

| Private insurance | |||

| Yes | 65 | −0.13 | (−0.36,0.31) |

| No | 38 | −0.34 | (−0.59,−0.02) |

| Parenting stress reported 3 months after surgery | |||

| Lowest third | 36 | −0.06 | (−0.38,0.27) |

| Middle third | 33 | −0.37 | (−0.61,0.01) |

| Highest third | 33 | −0.30 | (−0.58,0.05) |

| Adverse event | |||

| Yes | 54 | −0.35 | (−0.56,−0.09) |

| No | 54 | −0.10 | (−0.36,0.18) |

| Additional surgeries | |||

| Yes | 40 | −0.35 | (−0.59,−0.03) |

| No | 68 | −0.20 | (−0.42,0.04) |

Participants whose caregivers had a greater number of reports of patching at least 75% of prescribed time were more likely to have a better grating visual acuity than those with fewer such reports (p = 0.08 for Kruskall-Wallis test and p = 0.03 for Jonckheere-Terpstra test) (Table 3). Additionally the odds of achieving a grating acuity within normal limits decreased with decreasing numbers of reports of achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching (Table 4). Adjustment for IOL implantation, age at surgery, and presence of adverse events or additional surgeries did not substantially change the observed association between adherence and visual acuity.

Table 3. .

Treatment, Grating Visual Acuity Measured at 12 Months of Age (Median) and Reported Adherence to Prescribed Occlusion Therapy at 2, 3, and 6 Months after Surgery in IATS Participants

|

Overall |

IOL |

CL |

p† |

||||||||

|

n |

% |

Median Grating Acuity |

p* |

n |

% |

Median Grating Acuity |

n |

% |

Median Grating Acuity |

||

| Proportion of assessments in which the caregiver reported patching >75% of prescribed time | 0.08‡ | ||||||||||

| None | 21 | 19.4 | 0.97 | 14 | 25.5 | 1.10 | 7 | 13.2 | 0.80 | 0.14 | |

| Some | 46 | 42.6 | 0.80 | 21 | 38.2 | 0.97 | 25 | 47.2 | 0.80 | 0.38 | |

| All | 41 | 37.9 | 0.80 | 20 | 36.4 | 0.80 | 21 | 39.6 | 0.80 | 0.90 | |

Kruskall-Wallis test comparing visual acuity by reported adherence.

Kruskall-Wallis test comparing visual outcome by treatment given reported adherence.

p = 0.03 for Jonckheere-Terpstra test.

Table 4. .

Reported Adherence to Prescribed Occlusion Therapy at 2, 3, and 6 Months after Surgery and Odds of Achieving Grating Visual Acuity within Normal Limits 12 Months after Surgery in IATS Participants

|

Vision WNL |

Poorer Vision |

Crude |

Adjusted* |

||||

|

OR |

95% CI |

OR |

95% CI |

||||

| Overall | None | 8 (38.1%) | 13 | 0.36 | (0.12,1.05) | 0.45 | (0.15,1.38) |

| Some | 25 (54.3%) | 21 | 0.69 | (0.29,1.62) | 0.83 | (0.33,2.06) | |

| All | 26 (63.4%) | 15 | 1.0 | Ref | 1.0 | Ref | |

| IOL | None | 4 (28.5%) | 10 | 0.22 | (0.05,0.95) | 0.23 | (0.05,1.03) |

| Some | 10 (47.6%) | 11 | 0.49 | (0.14,1.72) | 0.65 | (0.18,2.37) | |

| All | 13 (65.0%) | 7 | 1.0 | Ref | 1.0 | Ref | |

| CL | None | 4 (57.1%) | 3 | 0.82 | (0.14,4.66) | 1.91 | (0.26,14.02) |

| Some | 15 (60.0%) | 10 | 0.92 | (0.28,3.03) | 1.37 | (0.36,5.21) | |

| All | 13 (61.9%) | 8 | 1.0 | Ref | 1.0 | Ref | |

Adjusted for type of surgery, age at surgery, and having had a complication or additional surgery for overall. For treatment-specific analyses, adjusted for age at surgery and having had a complication or additional surgery.

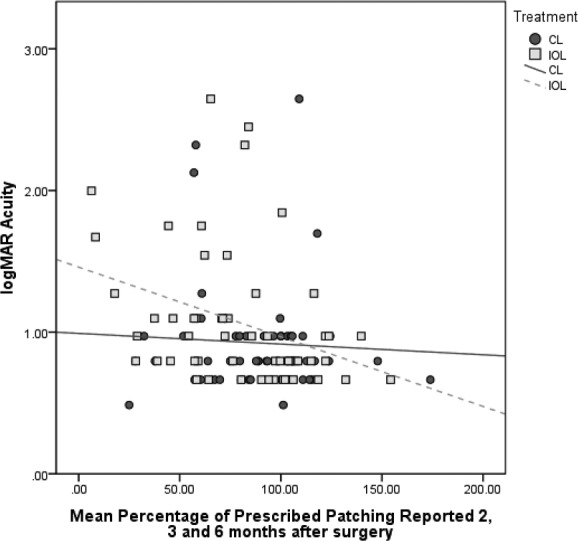

Of interest was the observation that the association between adherence and logMAR grating visual acuity was stronger among infants randomized to receive an IOL than among aphakic infants (Fig. 3). The mean percentage of prescribed patching reported by caregivers of pseudophakic children at 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery was significantly correlated with better grating visual acuity (rSpearman = −0.41, p < 0.01) as was the percentage of prescribed patching reported at each of the three time points (rSpearman = −0.41, p < 0.01; rSpearman = −0.31, p = 0.03; and rSpearman = −0.31, p = 0.03 at 2, 3, and 6 months post-surgery, respectively). None of the correlations between reported adherence and visual acuity were statistically significant among participants randomized to receive a contact lens (rSpearman = −0.03, p = 0.83; rSpearman = 0.01, p = 0.96; rSpearman = 0.12, p = 0.42; and rSpearman = −0.10, p = 0.49 for the mean and at 2, 3, and 6 months postsurgery, respectively). Similarly, among participants who received an IOL, those whose caregiver never reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching were 25% as likely to have vision WNL as those whose caregiver always reported achieving this level of adherence; among participants left aphakic, those whose caregivers never reported achieving 75% of prescribed patching were actually somewhat more likely to have a visual acuity WNL than those whose caregivers always achieved this level of patching after controlling for age at surgery, adverse event, and additional surgery. However, this association was not statistically significant.

Figure 3. .

logMAR acuity in the treated eye by the mean percentage of prescribed patching reported at 2, 3, and 6 months after surgery.

Relationship between Treatment and logMAR Grating Visual Acuity among Groups Defined by Adherence to Prescribed Patching

The final consideration was whether, given a particular amount of patching, treatment was associated with grating visual acuity (Table 3). Among groups defined by the number of assessments at which caregivers reported at least 75% of prescribed patching, the choice of treatment was not associated with logMAR grating visual acuity at 12 months of age. After adjustment for adherence, age at surgery, adverse events, and additional surgery, receiving an IOL was not associated with having a visual acuity WNL (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.39,2.63). Similarly, after adjusting for age at surgery, adverse events, and additional surgeries, receiving an IOL was not associated with achieving a visual acuity WNL among participants whose caregivers never reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.05,3.13), among those whose caregivers sometimes reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.23,5.20), and among those whose caregivers always reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.25,7.86).

Discussion

Adherence to occlusion therapy in the first 6 months following cataract extraction was found to be associated with visual acuity in infants treated between 1 and 7 months of age for unilateral congenital cataracts. This was particularly true in pseudophakic participants. These findings are consistent with most5,6,14 but not all previous assessments of the importance of occlusion therapy to vision rehabilitation in children born with congenital cataracts. The data reported here also suggest that the earlier observation of a lack of difference in visual acuity between aphakic and pseudophakic children11 at 1 year of age was unlikely to be related to an effect of treatment on adherence to patching, even though the treatment burden associated with contact lenses for aphakic children and spectacles for pseudophakic children is likely to differ.

However, the data reported here suggested that the observed association between grating visual acuity and adherence to patching soon after cataract extraction in infants may not be as strong as those reported in analyses of older children.1 This may be due in part to the age differences between the sample in this study and the samples assessed in other studies. Caregivers of older children may have an easier time adhering to prescribed patching if the child has better visual acuity or if the inter-ocular difference in visual acuity is minimal. It has yet to be determined whether or not the association between patching and visual acuity in the sample in this study becomes stronger as the IATS children age. Such an observation may support the concept that the relationship between visual acuity and patching is bidirectional.

Adherence to patching is likely also a proxy for adherence to other aspects of treatment, particularly use of refractive correction. In IATS, the two types of treatment represent different treatment burdens for caregivers. This difference in treatment burden is observed empirically since at each of the three time points, most (approximately 50%) of the caregivers of aphakic infants reported that the infant wore contact lenses at least 95% of waking hours and many of the infants wore contact lenses on an extended wear basis. In contrast, among pseudophakic participants, the median percentage of waking hours in which spectacles were worn was near 50%. Further, some pseudophakic infants (n = 10 six-months after surgery) did not require spectacles during the first year of life as their refractive error without spectacles was within the targeted range. Even so, 3 and 6 months after cataract extraction, adherence to patching was associated with spectacle use among pseudophakic participants (r = 0.26, p = 0.06 at 3 months and r = 0.25, p = 0.06 at 6 months of age) and contact lens use among aphakic participants (r = 0.27, p = 0.05 at 3 months and r = 0.40, p < 0.01 at 6 months). Thus, the findings regarding the association between adherence to patching may represent the impact of a combination of adherence both to occlusion and refractive correction rather than adherence to occlusion only.

There are a number of limitations to these analyses that must be considered. First, the IATS was powered to identify an overall difference in grating visual acuity between groups. Thus, there may not have been adequate power to identify, as statistically significant, small differences in adherence between treatment groups or in the impact of adherence on grating visual acuity. This is especially true in some of the subgroup analyses where the sample sizes were small. For example, there was only 40% power to detect, as statistically significant, a difference of 0.2 logMAR in visual acuity between aphakic and pseudophakic children with 20 per group. This was approximately the sample size for the subgroup for whom caregivers always reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching. The impact of small sample sizes also affects the size of correlations that we were able to identify. For the overall correlation between adherence and grating acuity, there was adequate power (i.e., >80%) to detect correlations of 0.26. However, within the group randomized to receive an IOL, there was adequate power to detect correlations of only 0.36 or higher. Small sample sizes in subgroup analyses likely explain the variation in observed correlation coefficients by some treatment and demographic factors, as well as the fact that most of these analyses failed to achieve statistical significance within groups defined by characteristics such as age at surgery and adverse events.

Subgroup analyses may also be problematic because although IATS participants were randomized to treatment, there may have been confounding when the population was subdivided. An attempt was made to control for important sources of confounding, such as age at surgery and adverse events, through stratified analyses and use of logistic regression of the bivariate outcome of visual acuity within normal limits, but the numbers were small and the resulting associations imprecise. Techniques to adjust for possible confounders in a continuous fashion, such as multiple linear regression, were unable to be used because of the inability to transform the visual acuity data into a normal distribution. It will be important to continue to evaluate whether the relationship between adherence to patching and visual acuity differs by treatment, age at surgery, or adverse events as the IATS sample gets older.

It would be ideal to have the ability to monitor adherence to occlusion from the time of surgery through the assessment of grating acuity. Therefore, another limitation of these analyses was the maximum of three assessments of adherence, and the variation in number of assessments because of differences in age at surgery and because caregivers did not complete all scheduled assessments. The analyses were limited to participants with at least two adherence assessments and to the first three assessments because grating visual acuity had been assessed for the majority of participants by 9 months after surgery. An additional concern was related to the summary definitions of adherence that were chosen. The primary measure of adherence was the mean percentage of prescribed patching reported by caregivers at the three time points. This measure was weighted towards the early months after surgery since two of the time points were obtained in the first 3 months after surgery. The proportion of caregivers patching at least 75% of the prescribed time decreased from 67% at 2 months after surgery to 43% at 6 months. To the extent that adherence changes systematically over time, a summary measure could have been misleading. However, the use of an average had the advantage of being weighted towards the early period when there was less likelihood of reverse causality in which visual acuity influences adherence instead of the other way around. Additionally, there was support for the validity of the methodology used because of a strong association between the average amount of prescribed patching over the three time points and the number (i.e., all, some, never) of adherence assessments at which the caregiver reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching (rSpearman = 0.85, p < 0.01). Further, the average amount of prescribed patching was highest among those who reported achieving at least 75% of prescribed patching on all assessments (X = 112% ± 18.4%); intermediate among those who reported this level of adherence on some assessments (X = 80% ± 16.2%); and lowest among those whose caregivers never reported achieving this level of adherence (X = 40.1% ± 17.2%). The amount of patching reported by caregivers may have overestimated the true amount of patching.15,16 An attempt was made to minimize concerns that parents would report what they thought clinicians wanted to hear; this was done by having the assessments completed centrally rather than within the clinical context and by asking caregivers to provide the specific times that the patch was worn. These methods are used successfully to assess dietary intakes17–19 and adherence to patching in other studies.20,21 Thus, the results discussed in this article have shown that caregivers, particularly of pseudophakic infants, who adhered better to clinicians' advice about patching during infancy, had children with a better vision outcome at 12 months of age compared with those who had relatively poorer adherence. However, the absolute amount of patching achieved by caregivers may not be valid.

In summary, the results suggested that adherence to occlusion therapy in the first 6 months after cataract surgery was associated with visual acuity at 12 months of age. Further, the data suggested that implanting an IOL in infants with unilateral congenital cataracts did not substantially affect the amount of time that infants are patched in the first 6 months following surgery, and that differences in patching were not likely contributors to the observed similarity between treatment groups in grating visual acuity at 12 months of age.9 Continued following of these children will be important to see whether or not there are changes in the relationship between treatment and patching during the second year of life when patching often becomes more difficult.

Appendix

The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group

Administrative Units and Participating Clinical Centers

Clinical Coordinating Center (Emory University): Scott R. Lambert MD (Study Chair), Lindreth DuBois MEd, MMSc (National Coordinator)

Data Coordinating Center (Emory University): Michael Lynn MS (Director), Betsy Bridgman, Marianne Celano PhD, Julia Cleveland MSPH, George Cotsonis MS, Carolyn Drews-Botsch PhD, Nana Freret MSN, Lu Lu MS, Azhar Nizam MS, Seegar Swanson, Thandeka Tutu-Gxashe MPH

Visual Acuity Testing Center (University of Alabama, Birmingham): E. Eugenie Hartmann PhD (Director), Clara Edwards, Claudio Busettini PhD, Samuel Hayley

Steering Committee: Scott R. Lambert MD, Edward G. Buckley MD, David A. Plager MD, M. Edward Wilson MD, Michael Lynn MS, Lindreth DuBois MEd, MMSc, Carolyn Drews-Botsch PhD, E. Eugenie Hartmann PhD, Donald F. Everett MA

Contact Lens Committee: Buddy Russell COMT, Michael Ward MMSc

Participating Clinical Centers (In order by the number of patients enrolled):

Medical University of South Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina (14): M. Edward Wilson MD, Margaret Bozic CCRC, COA

Harvard University; Boston, Massachusetts (14): Deborah K. VanderVeen MD, Theresa A. Mansfield RN, Kathryn Bisceglia Miller OD

University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, Minnesota (13): Stephen P. Christiansen MD, Erick D. Bothun MD, Ann Holleschau, Jason Jedlicka OD, Patricia Winters OD

Cleveland Clinic; Cleveland, Ohio (10): Elias I. Traboulsi MD, Susan Crowe BS, COT, Heather Hasley Cimino OD

Baylor College of Medicine; Houston, Texas (10): Kimberly G. Yen MD, Maria Castanes MPH, Alma Sanchez COA, Shirley York

Oregon Health and Science University; Portland, Oregon (9): David T. Wheeler MD, Ann U. Stout MD, Paula Rauch OT, CRC, Kimberly Beaudet CO, COMT, Pam Berg CO, COMT

Emory University; Atlanta, Georgia (9): Scott R. Lambert MD, Amy K. Hutchinson MD, Lindreth DuBois MEd, MMSc, Rachel Robb MMSc, Marla J. Shainberg CO

Duke University; Durham, North Carolina (8): Edward G. Buckley MD, Sharon F. Freedman MD, Lois Duncan, B.W. Phillips, FCLSA, John T. Petrowski, OD

Vanderbilt University: Nashville, Tennessee (8): David Morrison MD, Sandy Owings COA, CCRP, Ron Biernacki CO, COMT, Christine Franklin COT

Indiana University (7): David A. Plager MD, Daniel E. Neely MD, Michele Whitaker COT, Donna Bates COA, Dana Donaldson OD

Miami Children's Hospital (6): Stacey Kruger MD, Charlotte Tibi CO, Susan Vega

University of Texas Southwestern; Dallas, Texas (6): David R. Weakley MD, David R. Stager, Jr., Joost Felius PhD, Clare Dias CO, Debra L. Sager, Todd Brantley OD

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Robert Hardy PhD (Chair), Eileen Birch PhD, Ken Cheng MD, Richard Hertle MD, Craig Kollman PhD, Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp MD, (resigned), Cyd McDowell, Donald F. Everett MA

Medical Safety Monitor: Allen Beck MD

Footnotes

Supported by National Eye Institute Grants 5U10EY013272 and 5U10EY013287.

Disclosure: C.D. Drews-Botsch, None; M. Celano, None; S. Kruger, None; E.E. Hartmann, None

References

- 1. Lloyd IC, Dowler JG, Kriss A, et al. Modulation of amblyopia therapy following early surgery for unilateral congenital cataracts. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:802–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lundvall A, Kugelberg U. Outcome after treatment of congenital unilateral cataract. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:588–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruth AL, Lambert SR. Amblyopia in the phakic eye after unilateral congenital cataract extraction. J AAPOS. 2006;10:587–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis TL, Maurer D, Brent HP. Development of grating acuity in children treated for unilateral or bilateral congenital cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:2080–2095 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen RJ, Speedwell L, Russell-Eggitt I. Long-term visual outcome after extraction of unilateral congenital cataracts. Eye (Lond). 2010;24:1263–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chak M, Wade A, Rahi JS. British Congenital Cataract Interest Group. Long-term visual acuity and its predictors after surgery for congenital cataract: findings of the British Congenital Cataract Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4262–4269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lambert SR, Plager DA, Lynn MJ, et al. Visual outcome following the reduction or cessation of patching therapy after early unilateral cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1071–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. SR Lambert, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch CD, et al. Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group The infant aphakia treatment study: design and clinical measures at enrollment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mayer DL, Beiser AS, Warner AF, et al. Monocular acuity norms for the Teller Acuity Cards between ages one month and four years. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:671–685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drews-Botsch CD, Hartmann EE, Celano M. Predictors of adherence to occlusion therapy 3 months after cataract extraction in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. J APPOS. 2012;16:150–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Plager DA, Lynn MS, Buckley EG, et al. Complications, adverse events, and additional intraocular surgery 1 year after cataract surgery in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2330–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lambert SR, Lynn M, Drews-Botsch CD, et al. A comparison of grating visual acuity, strabismus, and reoperation outcomes among children with aphakia and pseudophakia after unilateral cataract surgery during the first six months of life. J AAPOS. 2001;5; 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index: Manual, Administration Booklet and Research Update. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; ; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lorenz B, Wörle J. Visual results in congenital cataract with the use of contact lenses. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1991;229:123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Awan M, Proudlock FA, Gottlob I. A randomized controlled trial of unilateral strabismic and mixed amblyopia using occlusion dose monitors to record compliance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1435–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simonsz HJ, Polling JR, Voorn R, et al. Electronic monitoring of treatment compliance in patching for amblyopia. Strabismus. 1999;7:113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baranowski T, Dworkin R, Henske JC, et al. The accuracy of children's self-reports of diet: Family Health Project. J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:1381–1385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Briefel RR, Kalb LM, Condon E, et al. The Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study 2008: study design and methods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:S16–S26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Livingstone MB, Robson PJ. Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:279–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newsham D. Parental non-concordance with occlusion therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:957–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newsham D. A randomised controlled trial of written information: the effect on parental non-concordance with occlusion therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:787–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]