Abstract

Cardiac toxicity is a major limitation in the use of doxorubicin (and related anthracyclins). ON 1910.Na (Estybon, Rogersitib, or 1910), a substituted benzyl styryl sulfone, is equally active as doxorubicin against MCF-7 human mammary carcinoma xenografted into nude mice. 1910 augments the antitumor activity of doxorubicin when given simultaneously. Furthermore, when given in combination, 1910 protects against cardiac weight loss and against morphological damage to cardiac tissues. Doxorubicin induces inactivation of glucose response protein 78 (GRP78), a principal chaperone that serves as the master regulator of the unfolded protein response (UPR). Inactivated GRP78 leads to an increase in misfolded proteins, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, activation of UPR sensors, and increased CHOP expression. 1910 prevents the inactivation of GRP78 by doxorubicin, and the combination, while more active against the tumor, protects against cardiac weight loss.

Keywords: cardiotoxicity, protein folding, chemotherapy, glucose responsive protein, doxorubicin

Introduction

Doxorubicin is an antibiotic with broad anticancer activity, widely used alone and in combination in the treatment of breast cancer, lymphomas, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Although it has hematopoietic and mucosal toxicity, cardiac arrhythmias, and alopecia as short-term toxicities, its principal long-term toxicity is cardiac. Disruption of mitochondria and fragmentation of cardiac myocytes lead to congestive heart failure in patients with increasing frequency at cumulative doses in excess of 500 mg/m2.1 Late cardiopathy has been recognized in adults treated during childhood for leukemia and other neoplasms at even lower doses.2 Cardiac toxicity has also occurred at lower doses during or after radiotherapy to the chest,3 paclitaxel,4 and trastuzumab.5 Chemical phenomena putatively related to cardiotoxicity are multiple: activation of NFκB, apoptosis with mitochondrial release of cytochrome C, liberation of iron from intracellular ferritin, generation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, inhibition of nucleic acid and its derivative protein synthesis, and intracellular metabolism of the drug to doxorubicinol, more potent than doxorubicin in gene suppression and in the inhibition of adenosine triphosphatases.6

Previous efforts to attenuate the cardiac toxicity by slow infusion of doxorubicin or with vitamins C or E, glutathione, N-acetylcysteine, and other reducing agents failed or achieved modest results only.7 Liposomal encapsulation has allowed delivery of greater dosage before cardiac toxicity appears.8 Dexrazoxane (ICRF 187, ADR529), an iron chelator, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of doxorubicin cardiac toxicity. Although dexrazoxane has been shown effective in several studies,9,10 it has not been widely adopted in clinical practice.

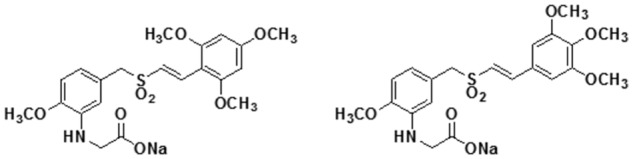

ON 01910.Na (Rogersitib, Estybon, Onconova Therapeutics, Newtown, PA), hereinafter as 1910, is a benzyl styryl sulfone (Fig. 1). This small molecule multikinase inhibitor has broad scale activity alone and in combination with other drugs against a number of human tumors in vitro and when xenografted in nude athymic mice.11,12 Normal cells are blocked at the G1-S checkpoint by 1910, but cancer cells proceed through this checkpoint and are arrested in G2-M. 1910 does not exert its anticancer effect by direct DNA damage or by binding tubulin. Recent data suggest that 1910 inhibits one or more phosphatases that ordinarily allow the unphosphorylated mitotic organizer RanGAP1-Sumo1 to catalyze cellular passage through the G2 phase and mitosis.13 Early RanGAP1-Sumo1 phosphorylation, presumably caused by inhibition of phosphatase activity by 1910, blocks cancer cells in G2. Abnormally prolonged persistence of G2 initiates cell death by apoptosis with nuclear membrane dissolution.13

Figure 1.

Structures of ON 01910.Na (Estybon, or 1910) and ON 01911.Na (1911), an inactive isomer.

ON 01911 (hereinafter as 1911) is an isomer of 1910, inactive in inhibiting tumor growth in vitro or in vivo (unpublished results) (Fig. 1).

We report here that 1910 decreases the lethal toxicity of doxorubicin while at the same time augmenting its antitumor effect against human breast cancer xenografted in nude athymic mice. Doxorubicin causes weight loss (without diarrhea), cardiac weight loss, and mitochondrial, myofibrillar, and chemical changes indicative of cardiopathy. These changes are prevented or attenuated by co-administration of 1910. Furthermore, biochemical changes in cardiac muscle correlate directly with morphological changes recognized by electron microscopy.

Results

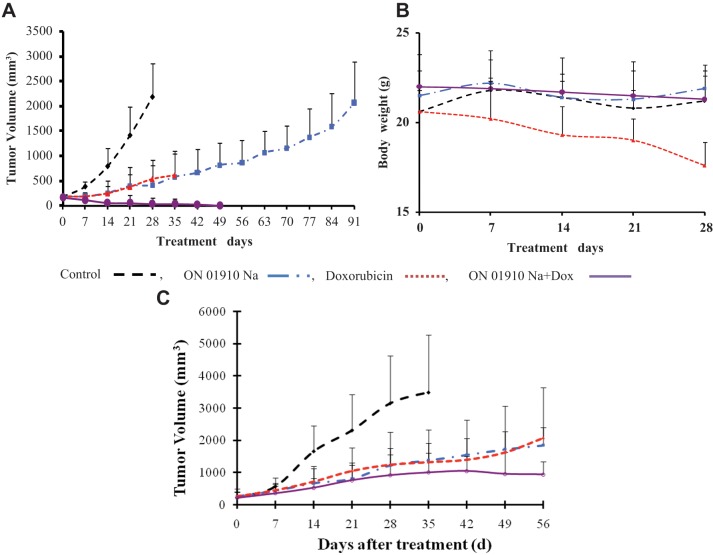

MCF-7 grew rapidly after subcutaneous transplantation in female nude mice (Fig. 2A). Chemotherapy was not administered until tumor growth of the group reached a mean of 200 mm3. Doxorubicin at 2.75 mg/kg/q2d intraperitoneally (i.p.) inhibited tumor growth when compared to control. Doxorubicin-treated animals survived for 35 days but were losing weight without diarrhea (Fig. 2B). Animals treated with 1910 at 200 mg/kg/q2d i.p. had growth inhibition identical to doxorubicin without toxicity; the treatment continued more than twice as long until the animals were euthanized because of excessive tumor size. When doxorubicin and 1910 were administered simultaneously, tumors disappeared, and the animals survived 2 weeks longer than doxorubicin alone (Fig. 2A). They did not lose weight (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Treatment of MCF-7 in estrogenized female nude mice. (A) Tumor inhibition by doxorubicin 2.75 mg/kg/q2d intraperitoneally (i.p.) (red) and by 1910 200 mg/kg/q2d i.p. (blue) is equivalent. Greater inhibition of mean tumor volume occurred for doxorubicin plus 1910 both at full doses (purple). All treatment groups are significantly less than saline-treated controls (black) (P < 0.05) at every point. The mean tumor volume of the combination treatment is significantly less than for the single drugs (P < 0.05) at day 35. At days 42 and 49, 5 mice survived with no measurable tumor. (B) Body weight of mice in experiment 2A. At day 28, mean weight of doxorubicin-treated mice is significantly less (P < 0.05) than the mean weight of the other 3 groups. (C) Equivalent tumor inhibition of doxorubicin 1.75 mg/kg/q2d i.p. and 1910 200 mg/kg/q2d i.p. Mean tumor volume of the combination at this lower dose is less than for individual drugs (not significant). All tumor volumes are significantly less than for saline controls (P < 0.05) at every time point after the first week.

A second experiment with doxorubicin at 1.75 mg/kg/q2d but the same dose of 1910 avoided lethal toxicity but again demonstrated benefit from the combination of the 2 drugs (Fig. 2C).

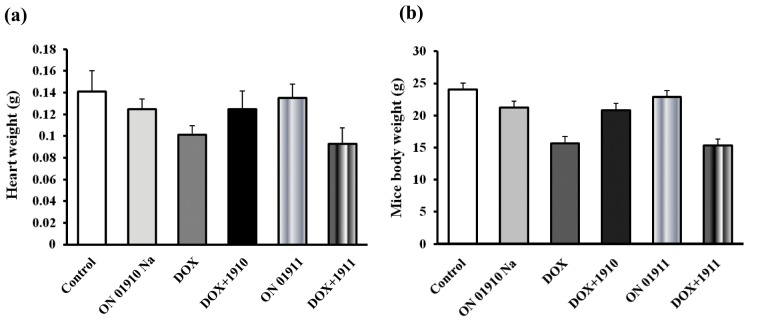

In a cardiotoxicity experiment, 36 female mice were ranked according to weight. Each successive cohort of 6 was then randomly allocated to control, 1911, doxorubicin, doxorubicin plus 1911, 1910, and doxorubicin plus 1910. Two mice from each group were euthanized on day 14 and the remaining 4 on day 28. Individual body and cardiac weights were measured (Fig. 3), and morphological specimens and biochemical determinations were made on combined hearts from each cohort. The mean cardiac and body weights of mice treated with doxorubicin or doxorubicin plus 1911 were less (P < 0.05) than the other 4 groups, which were not significantly different from one another.

Figure 3.

Cardiac and body weights on day 28 of non–tumor-bearing mice treated as in Figure 2A. 1911 dosing identical to 1910. (A) Mean cardiac weights of doxorubicin and doxorubicin plus 1911 are significantly less (P < 0.05) than the other 4 groups. (B) The mean body weights of the doxorubicin and doxorubicin plus 1911 groups are significantly less (P < 0.05) than the other 4 groups.

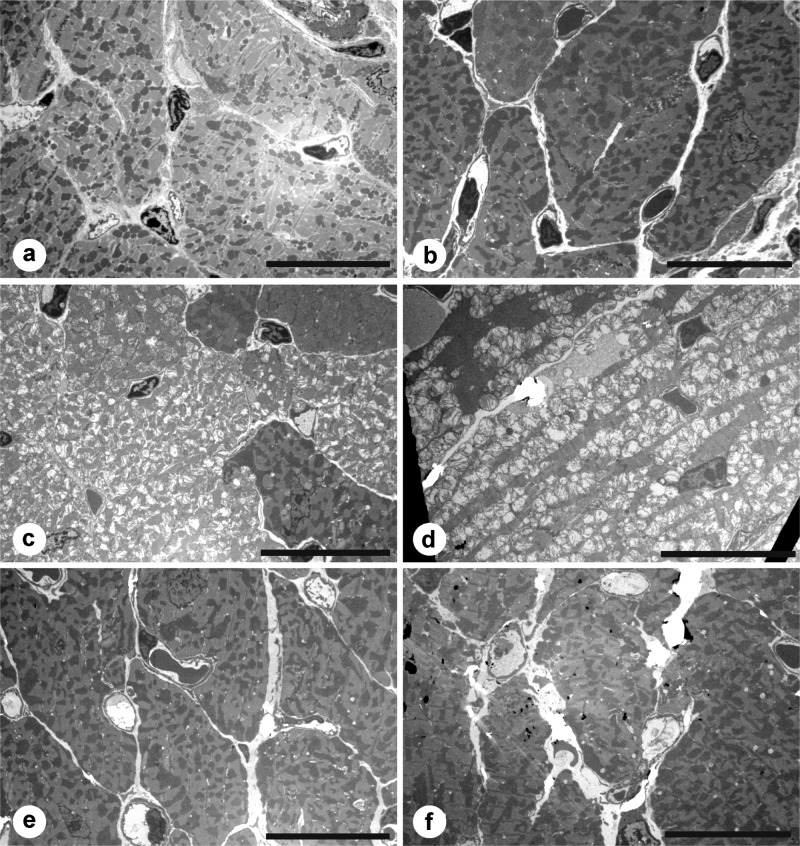

No morphological differences were appreciated when 6-µm specimens were stained with H&E, nor when 1-µm sections were stained with toluidine blue on either day 14 or day 28. On electron microscopy, however, fenestration of mitochondria and fragmentation of myofibrils were seen in specimens from day 28 treated with doxorubicin or doxorubicin plus 1911, the inactive isomer. Hearts exposed to 1910 alone, to 1911 alone, or to doxorubicin plus 1910 were nearly indistinguishable from hearts of the control animals (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Electron micrographs of representative cardiac tissues at 28 days of treatment. (A) Saline. (B) 1911. (C) Doxorubicin. (D) Doxorubicin plus 1911. (E) 1910. (F) Doxorubicin plus 1910. The vacuolated mitochondria and myofibrillar disruption in C and D are characteristic of severe cardiac damage from doxorubicin. Space bars equal 7 µm.

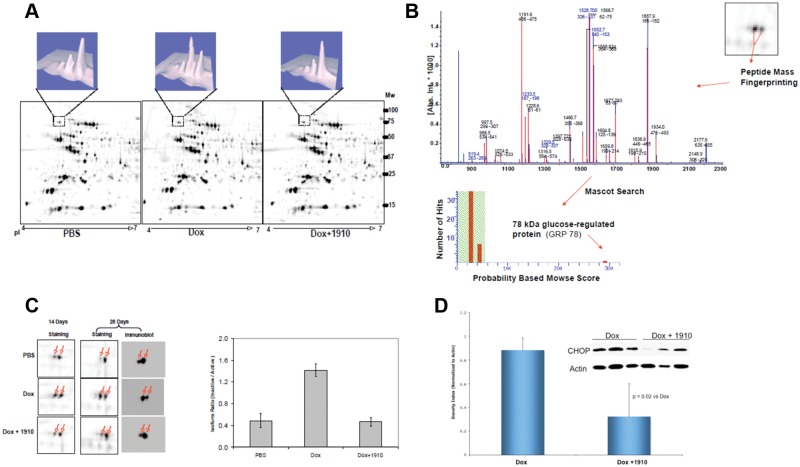

Decrease in cardiac protein synthesis by doxorubicin appears to be related to a new finding in the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), a member of the heat-shock protein 70 family that is a major regulator of the unfolded protein response pathway.14,15 Total GRP protein levels were not affected by doxorubicin, or doxorubicin plus 1910, when compared to controls as shown in 2-dimensional (2-D) electrophoresis (Fig. 5A). Peptide mass fingerprinting (Fig. 5B) identified GRP78 isoforms, however, and their identities were confirmed by 2-D Western blotting and immunoblotting (Fig. 5C). Compared to control, the GRP78 nonfunctional isoform was increased by doxorubicin treatment. This effect was reversed when 1910 was given with the doxorubicin. To assess the activity of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-regulated apoptosis pathways, we examined the expression of CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein) in the hearts of mice treated with doxorubicin, 1910, or the combination of doxorubicin plus 1910. 1910 alone did not show any CHOP expression (data not shown). The CHOP expression in the heart was increased with doxorubicin treatment and was reduced by 1910 treatment (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

(A) Typical 2-dimensional (2-D) images of heart tissues from mice treated with saline, doxorubicin, or doxorubicin plus 1910 for 28 days. Protein extracts were resolved with pH 4 to 7 immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips and then by 10% to 14% gradient SDS-PAGE. PDQuest image analysis revealed a major isoform switch for a protein identified as GRP78 via peptide mass fingerprinting. (B) Identification of GRP78 via MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy analysis. Peptide mass fingerprinting was internally calibrated by autotryptic peaks, resulting in high mass accuracy and a highly significant Mowse score (345). Mascot search results showed 27 measured mass peaks matched to the theoretical values of GRP78 tryptic peptides. (C) GRP78 isoform expression in response to doxorubicin or doxorubicin combined with 1910 treatment. Zoom view of 2-D images (left panel) showing the inactivated form increased significantly at 14 days and more prominently at 28 days in mice treated with doxorubicin alone. This effect was blocked by the simultaneous administration of 1910. The isoform expression at 28 days was also confirmed by 2-D immunoblot. The ratio of inactive to active GRP78 isoform calculated by PDQuest software (right panel) shows a significant increase after 28 days of doxorubicin treatment. Such an effect is reversed by the simultaneous administration of 1910. (D) Effect of doxorubicin and doxorubicin plus 1910 on endoplasmic reticulum stress apoptotic signaling in the heart. Western blots of the heart homogenate after 28 days of treatment. Proapoptotic signal induced by CHOP was elevated with doxorubicin treatment. This effect was reversed by 1910.

Discussion

The benzyl styryl sulfone ON 01910.Na (1910, Rogersitib or Estybon) was equiactive with doxorubicin in inhibiting MCF-7 human breast cancer xenograft growth in nude athymic mice. The combination of 1910 and doxorubicin was significantly more active in tumor inhibition. Doxorubicin at the dose we chose, however, produced lethal toxicity in nude mice (Fig. 2A). Absence of diarrhea and normal small intestinal mucosa on light microscopy suggested other mechanisms of lethality. The decrease in cardiac weight observed in doxorubicin-treated animals was largely prevented by co-administration of 1910 but not by its inactive isomer 1911 (Fig. 3). Doxorubicin alone or doxorubicin with the inactive isomer 1911 caused classic morphological changes in cardiac muscle by electron microscopy. These changes were largely prevented when 1910 was given with doxorubicin (Fig. 4). The exact pharmacological mechanisms for this abrogation of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity with improvement in anticancer effects are unknown, but changes in the unfolded protein response appear to be contributive. The observation emphasizes, however, that the effect on cardiac myomytes and on tumor cells may be fundamentally different.

The ER is a major site for protein as well as for lipid and sterol synthesis.16-18 Ribosomes attached to the ER membranes release newly synthesized peptides into the ER lumen, where protein chaperones and foldases assist in the proper posttranslational modification and folding of these peptides.17,19 The properly folded proteins are then released to the Golgi complex for final modification and are transported to their final destination. If the influx of misfolded or unfolded peptides exceeds the ER folding and/or processing capacity, ER stress ensues. Three proximal ER stress sensors have been identified.17,18,20-22 They are the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE 1), the protein kinase RNA (PKR)–like ER protein kinase (PERK), and the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF-6). These sensors trigger activation of pathways, termed the unfolded protein response (UPR), which acts to alleviate ER stress. The UPR can achieve this by slowing down protein synthesis and/or by turning up the production of protein chaperones needed for proper protein folding, or if unsuccessful, by degrading the unfolded proteins.16,17

GRP78 (also known as immunoglobulin binding protein [BiP]), a member of the heat-shock protein 70 family, is of particular importance in the maintenance of ER homeostasis and as a regulator of the UPR.16-18 GRP78 is the major ER resident chaperone involved in the transport of essential proteins into the ER, their proper folding, and the transport of terminally misfolded proteins into the proteosome for degradation. There is increasing evidence that the UPR is activated in various solid tumors, including breast cancer and prostate cancer.23,24

GRP78 also serves as the master regulator of the UPR by binding and inactivating the stress sensors at their ER luminal surface.25 Indeed, GRP78 knockdown by siRNA technology induces an unfolded protein response in the cultured cells.26

Doxorubicin induces ER stress by activating ATF4, a downstream effector of ER kinase-signaling pathways.27 The total expression of GRP78 is not altered by doxorubicin,28 a result confirmed by the present data. However, our 2-D mass spectroscopy and Western blot analysis from the hearts of animals treated with and without doxorubicin for up to 28 days show the expression of the 2 GRP78 isoforms in the heart. Interestingly, one isoform of GRP78 is increased in the doxorubicin-treated heart as compared to the untreated, and this effect is reversed by the treatment with 1910 (Fig. 5C). Previous studies have shown that this GRP78 isoform is modified and becomes inactive; that is, it cannot bind to misfolded proteins, but it can be converted to the unmodified, active form.29-31 In addition, the posttranslational formation of modified GRP78 depends on the rate of protein influx into the cell in relation to the amount of available UPR proteins.29 Such posttranslational modification has been shown to be caused by the changes in ADP ribosylation and can also be induced by nutrient starvation, low temperature, and treatments with cycloheximide or amino acid analogs,32,33 conditions suitable for UPR-induced apoptosis. On the contrary, isoform switch by 1910 from inactive to active GPR78 is indicative of protective UPR. Therefore, doxorubicin-induced inactivation of GRP78 in the heart tissue is likely a mechanistic pathway of the inhibitory action of doxorubicin on the UPR and protein synthesis and may represent the basis for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity.

Over a range of cell stress, the UPR is protective. However, when ER stress is sufficiently intense or prolonged, the UPR activates cell death pathways.21,34 ER stress-mediated cell death pathways involve PERK activation with enhanced translation of the transcription factor, CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein), also known as growth arrest– and DNA damage–inducible gene 153 (GADD153).21,34,35 CHOP, in turn, inhibits expression of the antiapoptotic factor, BCL-2, and may activate ER resident caspases.21,34 It is of interest in this regard that our data and that of others suggest that CHOP activity is increased in response to doxorubicin treatment,36 and this effect is ameliorated by 1910. Our results suggest that 1910 enhances the protective UPR by increasing the levels of active GRP78, which in turn protects the cells by reducing the PERK-induced CHOP activation. At present, the mechanisms that determine the balance between cell compensation and induction of apoptosis are poorly understood but may relate in part to differences in the time course of PERK and IRE1 activity and/or the half-life of CHOP and ATF4 mRNA.22,35,37

1910 (Estybon) is currently undergoing clinical trial alone and in combination with chemotherapeutic agents of established clinical usefulness. Potentiation of the antineoplastic effect of doxorubicin together with reduction of its cardiac toxicity supports clinical investigation of this combination.

Materials and Methods

Mice, tumors, and drugs

Nude female Nu/Nu mice, 17 to 25 g, were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed 5 to a cage with standard chow and water ad libitum. All environmental exposure was limited to autoclaved materials, filtered air, and sterile handling. All manipulations were accomplished in a laminar flow hood. After 1 week of quarantine, they were implanted subcutaneously with a 360-µg estradiol tablet (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). After 24 hours, 2 × 106 MCF-7 breast cancer cells were implanted subcutaneously in the flank of each mouse. Tumor measurements were made weekly by calipers and volume calculated by L × W2 × 0.52. Treatment began when mean tumor size for the group had grown to 200 mm3 or larger. Animals were treated every second day i.p. with doxorubicin dissolved in saline at doses of 2.75 mg/kg/q2d or 1.75 mg/kg/q2d in different experiments. 1910 was given by separate i.p. injection at a dose of 200 mg/kg/q2d. The combined treatments of doxorubicin and 1910 were given within moments of one another. Control animals received an equal volume of saline. Treatments continued every second day until death or until termination of the experiment.

In toxicity experiments, tumors were not implanted. Each cohort contained an animal given doxorubicin, 1910, 1911, doxorubicin plus 1911, doxorubicin plus 1910, and a saline control. All animals were weighed, and successive cohorts by weight were randomized within each cohort. Two cohorts were euthanized by CO2 inhalation on day 14 and the remaining 4 cohorts on day 28.

The heart was excised immediately after death. The aorta and pulmonary arteries were trimmed to 1 mm in length. Blood was drained from the heart; it was washed with phosphate buffered saline, blotted, and weighed on an electronic balance. The heart then was dissected with new razor blades in a dish on ice to produce 1-mm slices through the ventricle, which were immediately placed in 3% glutaraldehyde, 10% formalin, or frozen at −80°C for biochemical study. The time elapsed from death to cardiac excision was approximately 2 minutes and from excision to preparation of specimens another 2 minutes.

Specimens for light and electron microscopy (EM) were further processed; EM specimens were first fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. Both were dehydrated in steps of ethyl alcohol and embedded in either paraffin or epon, respectively. Tissues were sectioned at 6 µm for H&E staining, at 1 µm for toluidine blue staining, and at 50 to 60 nm for EM after staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Doxorubicin in solution was purchased from Bedford Laboratories (Bedford, OH). 1910 and 1911 were kindly provided by Onconova Therapeutics. They were dissolved in a small volume of dimethyl sulfoxide and then diluted in phosphate buffered saline prior to each experiment.

Biochemical methods

Frozen heart tissues were processed for each treatment group by grinding in liquid N2. Powders were thawed, dissolved in lysis buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged. Proteins in the supernatant were precipitated with acetone, resolubilized, and measured.

In the first dimension of 2-D gel electrophoresis, 50 µg was loaded on different IPG strips. Isoelectric focusing within the strips was performed before the second dimension was accomplished with different buffers, positioned against 10% to 14% SDS polyacrylamide gel. The gels were then fixed with 50% acidified methanol and the spots visualized by fluorescent dye. Spot volumes were determined by density/area integration and normalized among gels to total spot volume on each gel. Spots were excised robotically and destained with ammoniated acetonitrile. Overnight trypsinization allowed extraction of tryptic peptides with acidified acetonitrile.

Dissolved peptides from each spot were mixed with matrix solution and applied to wells for MALDI-TOF spectrometric analysis. Proteins were identified by matching peptide mass fingerprints with the Swiss-Prot protein database for Homo sapiens. Experimental details and reagents are given in the online supplementary methods.

Western blot analysis was performed on 20 µg of protein in 10% to 14% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% powdered milk, the membrane was probed with dilute anti-GRP78, anti-P53, anti-lamin A/G, anti-CHOP, and anti–β-actin murine antibodies. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was used.

Statistical methods

Comparisons of mean tumor volume, mean body weight, and mean heart weight between groups were made for each day by analysis of variance (ANOVA). For variables having nonhomogeneity of variances between groups, a log transformation of the data was first performed before proceeding with ANOVA. The Student-Newman-Keuls procedure was used to test multiple comparisons between treatment groups for a 0.05 level of significance.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Onconova Therapeutics has provided funding for grants to both Dr. James F. Holland and Dr. Salim Merali.

This work was supported by a grant from the T.J. Martell Foundation for leukemia, cancer, and AIDS research to Dr. James F. Holland.

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Genes & Cancer website at http://ganc.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Ibrahim NK, Hortobagyi GN, Ewer M, et al. Doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure in elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer, with long-term follow-up: the M.D. Anderson experience. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43:471-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pein F, Sakiroglu O, Dahan M, et al. Cardiac abnormalities 15 years and more after adriamycin therapy in 229 childhood survivors of a solid tumour at the Institut Gustave Roussy. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:37-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Billingham ME, Bristow MR, Glatstein E, Mason JW, Masek MA, Daniels JR. Adriamycin cardiotoxicity: endomyocardial biopsy evidence of enhancement by irradiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1977;1:17-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gianni L, Salvatorelli E, Minotti G. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients: synergism with trastuzumab and taxanes. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7:67-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Russell SD, Blackwell KL, Lawrence J, et al. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy: a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3416-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G, Gianni L. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:185-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatterjee K, Zhang J, Honbo N, Karliner JS. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology. 2010;115:155-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alberts DS, Muggia FM, Carmichael J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liposomal anthracyclines in phase I/II clinical trials. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:53-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Speyer JL, Green MD, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, et al. ICRF-187 permits longer treatment with doxorubicin in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:117-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Gerber MC, et al. Cardioprotection with dexrazoxane for doxorubicin-containing therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1318-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddy MV, Mallireddigari MR, Cosenza SC, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of (E)-styrylbenzylsulfones as novel anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2008;51:86-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gumireddy K, Reddy MV, Cosenza SC, et al. ON01910, a non-ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor of Plk1, is a potent anticancer agent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:275-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oussenko I, Holland JF, Reddy EP, Ohnuma T. ON 01910.Na, a clinical stage anticancer mitotic inhibitor, produces prolonged hyperphosphorylation of RanGAP1·SUMO1 as a potential mechanism of G2/M arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4968-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merksamer PI, Papa FR. The UPR and cell fate at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1003-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Merksamer PI, Trusina A, Papa FR. Real-time redox measurements during endoplasmic reticulum stress reveal interlinked protein folding functions. Cell. 2008;135:933-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569:29-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:716-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorlach A, Klappa P, Kietzmann T. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling, and redox control. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1391-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marciniak SJ, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1133-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scriven P, Coulson S, Haines R, Balasubramanian S, Cross S, Wyld L. Activation and clinical significance of the unfolded protein response in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1692-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. So AY, de la Fuente E, Walter P, Shuman M, Bernales S. The unfolded protein response during prostate cancer development. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:219-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foufelle F, Ferre P. Unfolded protein response: its role in physiology and physiopathology. Med Sci (Paris). 2007;23:291-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suzuki T, Lu J, Zahed M, Kita K, Suzuki N. Reduction of GRP78 expression with siRNA activates unfolded protein response leading to apoptosis in HeLa cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;468:1-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu S, Ko YS, Teng MS, et al. Adriamycin-induced cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell apoptosis: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1595-607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim SJ, Park KM, Kim N, Yeom YI. Doxorubicin prevents endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:463-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Freiden PJ, Gaut JR, Hendershot LM. Interconversion of three differentially modified and assembled forms of BiP. EMBO J. 1992;11:63-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gething M-J. Role and regulation of the ER chaperone BiP. Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10:465-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Laitusis AL, Brostrom MA, Brostrom CO. The dynamic role of GRP78/BiP in the coordination of mRNA translation with protein processing. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:486-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leno GH, Ledford BE. ADP-ribosylation of the 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein during nutritional stress. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:205-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ledford BE, Leno GH. ADP-ribosylation of the molecular chaperone GRP78/BiP. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;138:141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Faitova J, Krekac D, Hrstka R, Vojtesek B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:488-505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2007;318:944-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lai HC, Yeh YC, Ting CT, et al. Doxycycline suppresses doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and cellular apoptosis in mouse hearts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;644:176-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rutkowski DT, Arnold SM, Miller CN, et al. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]