Abstract

We report small angle X-ray and neutron scattering measurements that reveal that mixtures of the redox-active lipid bis(11-ferrocenylundecyl)dimethylammonium bromide (BFDMA) and dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) spontaneously form lipoplexes with DNA that exhibit inverse hexagonal nanostructure (HIIc). In contrast to lipoplexes of DNA and BFDMA only, which exhibit a multilamellar nanostructure (Lαc) and limited ability to transfect cells in the presence of serum proteins, we measured lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE with the HIIc nanostructure to survive incubation in serum and to expand significantly the range of media compositions (e.g., up to 80% serum) over which BFDMA can be used to transfect cells with high efficiency. Importantly, we also measured the oxidation state of the ferrocene within the BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes to have a substantial influence on the transfection efficiency of the lipoplexes in media containing serum. Specifically, whereas lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and DOPE transfect cells with high efficiency, lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA and DNA lead to low levels of transfection. Complementary measurements using SAXS reveal that the low transfection efficiency of the lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA and DOPE correlates with the presence of weak Bragg peaks and thus low levels of HIIc nanostructure in solution. Overall, these results provide support for our hypothesis that DOPE-induced formation of the HIIc nanostructure of the BFDMA-containing lipoplexes underlies the high cell transfection efficiency measured in the presence of serum, and that the oxidation state of BFDMA within lipoplexes with DOPE substantially regulates the formation of the HIIc nanostructure and thus the ability of the lipoplexes to transfect cells with DNA. More generally, the results presented in this paper suggest that lipoplexes formed from BFDMA and DOPE may offer the basis of approaches that permit active and external control of transfection of cells in the presence of high (physiologically relevant) levels of serum.

Introduction

The ability to design soft materials that deliver DNA to specific populations of cells at desired times, or to sub-populations of cells within a larger colony or tissue, would be broadly useful in a variety of in vitro (e.g., basic biological and biomedical research1–10 or tissue engineering11–18) and in vivo contexts (e.g., development of new gene-based therapies19–33). Although a range of nanoscopic assemblies, including those formed from cationic lipids and polymers,34–38 have been reported to form complexes with DNA and enable the delivery of DNA to cells, the majority of these complexes are, by design, able to transfect cells from the time of their formation (and, thus, they do not readily permit control over ‘activation’ or ‘inactivation’ in ways that provide methods for spatial and temporal control over delivery and/or internalization). Several recent studies have reported on nanoscale assemblies formed from “functional” lipids that are redox-active,39–48 pH-responsive,39, 49, 50 light-sensitive51 or chemically or enzymatically cleavable.39, 52–54 These functional lipids respond to changes in chemical environments inside cells in ways that can help promote more efficient intracellular trafficking of DNA (e.g., endosomal escape, etc.), but these past approaches do not, in general, provide methods for control over the activation or inactivation of lipid/DNA assemblies in extracellular environments. In this paper, we report the design of complexes comprised of DNA, a ferrocene-containing lipid, and a zwitterionic lipid that are stable in physiologically-relevant concentrations of serum and permit control over cell transfection via a change in the redox state of the ferrocene groups of the ferrocene-containing lipid (e.g., whether they are present in the reduced or oxidized redox state).

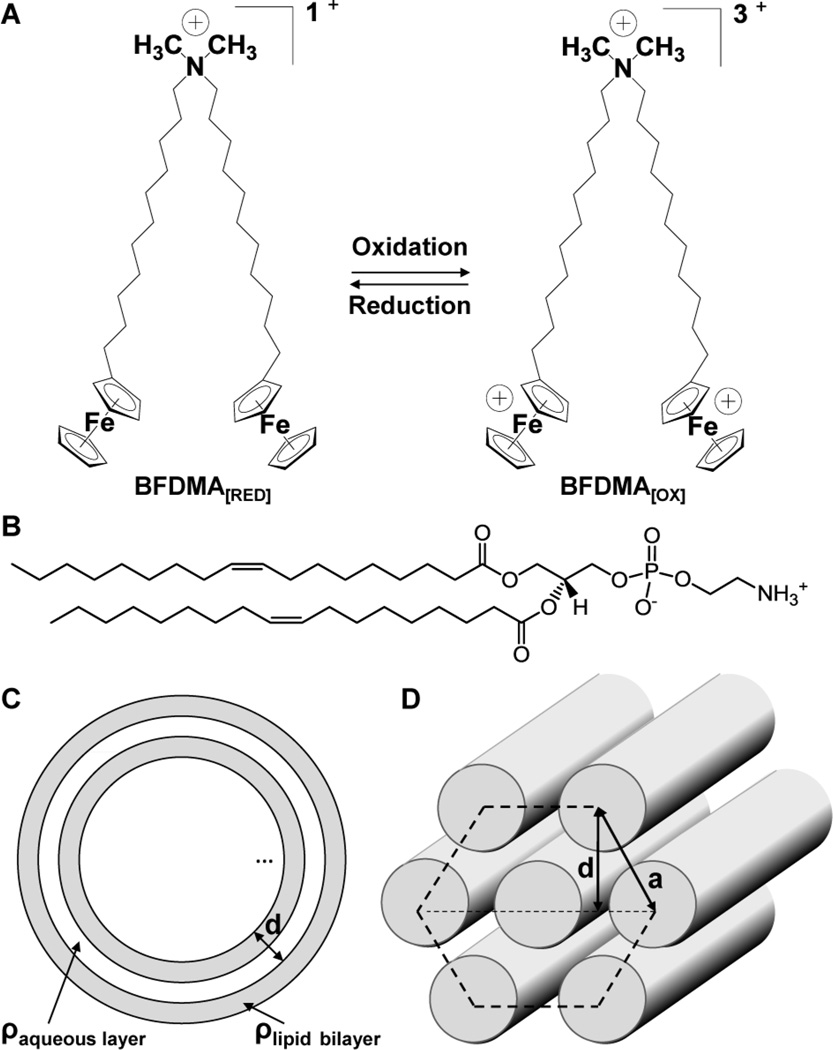

The study reported in this paper builds upon past reports from our group on the characterization of lipid/DNA complexes (“lipoplexes”) formed using the ferrocene-containing cationic lipid, bis(11-ferrocenylundecyl)dimethylammonium bromide (BFDMA, Fig. 1A).55–61 These studies demonstrated that lipoplexes formed using plasmid DNA and reduced BFDMA promote high levels of cell transfection in vitro when administered to mammalian cells in serum-free media.55 In contrast, oxidation of the ferrocene groups of BFDMA to ferrocenium (using either chemical57, 61 or electrochemical55 methods) leads to lipoplexes that mediate low levels of transfection under otherwise identical conditions. We have also demonstrated that changes in the oxidation state of ferrocene can lead to changes in a range of different structural and physical properties of BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes that are relevant to transfection.55–59, 61, 62 For example, both cryo-TEM images and small angle neutron scattering (SANS)58, 61 spectra reveal that lipoplexes formed using reduced BFDMA and DNA possess a multilamellar, Lαc nanostructure (Fig. 1C) with a lamellar periodicity of 5.2 nm and an overall aggregate size of 50 to 150 nm. In contrast, the nanostructure of complexes formed from oxidized BFDMA and DNA have no such lamellar periodicity, i.e., there is no Bragg peak in the SANS spectra and cryo-TEM images indicate the formation of loose and disordered aggregates.58 These past results, when combined, hint at materials and methods that could ultimately enable active and external control of the transfection of cells via manipulation (either electrochemically or chemically) of the oxidation state of lipoplexes containing BFDMA.

Fig. 1.

(A) Structure of BFDMA, a redox-active cationic lipid. The charge of BFDMA can be cycled between +1 (reduced) and +3 (oxidized) by oxidation or reduction of the ferrocenyl groups at the end of each hydrophobic tail; (B) Structure of DOPE; (C) Schematic illustration of a multilamellar vesicle nanostructure; (D) Schematic illustration of a hexagonal nanostructure.

Whereas our past studies were performed with lipoplexes formed from BFDMA and DNA, the study reported in this paper moves to investigate the properties and nanostructures of lipoplexes formed when BFDMA is mixed with a second lipid (DOPE; Fig. 1B). Our investigation of BFDMA in lipoplexes formulated with DOPE was motivated by the observation that the use of mixtures of lipids, in general, provides a versatile approach for tuning a range of properties of lipoplexes that can influence transfection efficiency.63 In the context of this current study, we investigated mixtures of BFDMA and DOPE because (i) incorporation of DOPE into lipoplexes has been shown in some past studies to lead to the formation of mixed-lipid lipoplexes that promote high levels of cell transfection in media containing high levels of serum,64–68 and (ii) recent observations have revealed that serum has a deleterious influence on both the structure60 and the transfection activity56 of lipoplexes formed using reduced BFDMA. We hypothesized that incorporation of DOPE into lipoplexes containing BFDMA might help overcome a significant and unresolved barrier to the potential use of BFDMA in a variety of biological contexts where serum will be present. We also note here that past studies of DOPE-containing lipoplexes have reported that DOPE promotes formation of lipoplexes with an inverse hexagonal nanostructure (Fig. 1D),63, 68–73 and causes fusion of lipoplexes with cell membranes,63, 69, 72, 74–76 observations that hint at fundamental underlying mechanisms by which DOPE, when mixed with cationic lipids, can promote high levels of transfection in the presence of serum.

The study reported in this paper explores the influence of DOPE on the nanostructure of lipoplexes containing BFDMA by using small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and SANS,71, 77 and investigates whether changes in the nanostructure of the lipoplexes induced by DOPE lead to changes in transfection efficiencies in the presence of serum at concentrations typical of several different laboratory and physiological contexts (e.g., at levels commonly used in in vitro laboratory experiments or at levels encountered in physiological media, i.e., in blood or extracellular matrices).78, 79 A second key goal of the study reported in this paper was to determine if changes in the oxidation state of BFDMA within lipoplexes formed from mixtures of BFDMA and DOPE would lead to substantial changes in the transfection efficiencies of the lipoplexes (e.g., as observed in our past studies of BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes in serum-free media).55–59, 61 To aid in the interpretation of these transfection experiments, we report also the physical properties of the lipoplexes investigated in terms of their surface charge and apparent size in solution using zeta potential analysis and dynamic light scattering (DLS), respectively.

Experimental section

Materials

Bis-(11-ferrocenylundecyl)dimethylammonium bromide (BFDMA) was synthesized according to methods published elsewhere.80–82 Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) was purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, Alabama) in powdered form. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ) was used to prepare all buffers and salt solutions with the exception of samples for small angle neutron scattering (SANS), where deuterium oxide (D2O) was used. Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), OptiMEM cell culture medium, phosphate-buffered saline, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and bovine serum (BS) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Plasmid DNA encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-N1 (4.7 kbps, >95% supercoiled) and firefly luciferase (pCMV-Luc, >95% supercoiled) were purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals (San Francisco, CA). Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kits were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Glo Lysis Buffer and Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay kits were purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI). All commercial materials were used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted.

Experimental methods

Preparation of reduced and oxidized BFDMA and BFDMA-DOPE solutions

Solutions of reduced BFDMA were prepared by dissolving a desired mass of reduced BFDMA in chloroform at 10 mg/ml. Nitrogen gas was used to evaporate most of the chloroform from a clean glass tube containing the lipid. This partially dried sample was placed under vacuum in a desiccator overnight. Aqueous Li2SO4 (1 mM) was added and tip sonication was used to provide a homogeneous solution of 1 mM BFDMA. Solutions of BFDMA-DOPE were prepared in a similar way by dissolving a desired mass of DOPE into chloroform at 10 mg/ml. Chloroform-based solutions of BFDMA and DOPE at 10 mg/ml were then mixed to the desired molar ratio prior to drying with N2, desiccating overnight and reconstituting in Li2SO4, as described above. Solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA or oxidized BFDMA-DOPE were subsequently prepared by electrochemical oxidation of 1.0 mM reduced BFDMA solution at 75 °C, in the presence or absence of DOPE, using a bipotentiostat (Pine Instruments, Grove City, PA) and a three electrode cell to maintain a constant potential of 600 mV between the working electrode and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode, as described previously.55 Platinum mesh (4.0 cm2) was used as the working and counter electrodes. The extent of oxidation of BFDMA was followed by monitoring the current passed at the working electrode and by using UV/visible spectrophotometry.55–58

Preparation of lipoplexes for transfection assays

Lipoplexes of reduced or oxidized BFDMA or BFDMA-DOPE were prepared in the following manner. A solution of plasmid DNA (24 µg/mL in water) was added to a vortexing solution of aqueous Li2SO4 containing an amount of reduced or oxidized BFDMA or BFDMA-DOPE sufficient to give the final lipid concentration of 8 µM BFDMA for cell transfection experiments. This procedure resulted in the desired charge ratio of either BFDMA or BFDMA-DOPE and DNA in solution (where the charge ratio (CR) is defined as the mole ratio of the positive charges in the cationic lipid to negative charges of the DNA phosphate groups). The CRs investigated in this study were limited to 1.1:1 for BFDMARED-containing samples and 3.3:1 for BFDMAOX-containing samples, selected for relevance to our past transfection experiments.55–57 We note that complexes formed from reduced BFDMA and DNA at a CR of 1.1:1 contain the same molar concentrations of BFDMA and DNA as complexes formed by oxidized BFDMA and DNA at a CR of 3.3:1,58 and that DOPE is zwitterionic and therefore does not affect the final CR. The sample volume used for cell transfection experiments was 50 µL. Lipoplexes were allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min before use.

Protocols for transfection and analysis of gene expression

COS-7 cells used in transfection experiments were grown in clear or opaque polystyrene 96-well culture plates (for experiments using pEGFP-N1 and pCMV-Luc, respectively) at initial seeding densities of 15 000 cells/well in 200 µL of growth medium (90% DMEM, 10% FBS, penicillin 100 units/mL, streptomycin 100 µg/mL). After plating, all cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. At approximately 80% confluence, the culture medium was aspirated and replaced with either 200 µL of serum-free medium (OptiMEM), or a mixture of bovine serum (BS) and OptiMEM at different volume-based ratios up to 100% BS, followed by addition of 50 µL of the lipoplex sample to achieve a final concentration of 8 µM BFDMA in the presence of cells. We note that the addition of the 50 µL sample of lipoplexes introduces a 20% dilution [50 µL/(50 µL +200 µL)*100%] of the concentration of BS in the final solutions in which cells were bathed. Lipoplexes prepared as described above were added to assigned wells via pipette in replicates of three, and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, at which point the lipoplex-containing medium was aspirated from all wells and replaced with 200 µL of growth medium (composition given above). Samples were incubated for an additional 48 h prior to characterization of transgene expression. For experiments conducted using lipoplexes formed from pEGFP-N1, cell morphology and relative levels of EGFP expression were characterized using phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Luciferase protein expression was determined using a commercially available luminescence-based luciferease assay kit using the manufacturer’s specified protocol. Samples were compared with signals from control wells and/or normalized against total cell protein in each respective well using a commercially available BCA assay kit (Pierce). Luciferase protein expression data was analyzed for statistical significance using the Student’s t-test with α = 0.05. In the text below, when we refer to “significant differences” between our data, we are referring to the results of this test.

Preparation of lipoplexes for characterization by SAXS and SANS

All samples characterized by SAXS and SANS were formulated using reduced or oxidized BFDMA, DOPE and plasmid DNA encoding EGFP (pEGFP-N1). Samples were prepared using 1 mM Li2SO4 in either D2O for SANS or deionized water for SAXS. A stock solution of BFDMA and DOPE (1 mM BFDMA and relevant φDOPE) was diluted with a small volume of DNA stock solution (2.0 mg/ml in H2O for SAXS and 2.9 mg/ml in D2O for SANS resulting in a 10% and 13% dilution, respectively) and vortexed for 5 s. The CR used in all scattering experiments was 1.1:1, the same CR as used in the transfection experiments, as noted above. For SAXS analysis, samples of reduced BFDMA-containing lipoplexes, diluted in OptiMEM medium and 50% (v/v) BS, in the presence of and in the absence of DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71 and 0, respectively), were also characterized. We note that the absolute concentrations of BFDMA used in the SANS and SAXS experiments (0.3 to 0.9 mM) were substantially higher than those of the transfection experiments (8 µM). These higher concentrations were necessary to obtain a sufficient intensity of scattered neutrons or X-rays in SANS or SAXS experiments, respectively. All samples were also observed between crossed polars for evidence of optical birefringence.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

SAXS was performed using a 4m Rigaku small angle X-ray system with 2-d multi-wire detector. The energy of the incident beam was 40 W. As detailed elsewhere,83 the samples characterized by SAXS were centrifuged using a Sorvall Biofuge Primo centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) at 2000 g for 10 minutes inside 1 mm diameter, 0.01 mm thick quartz capillary tubes (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA) to obtain a precipitate of lipoplexes. The detector was mounted at a distance of 0.55 m from the sample, allowing access to a q range of 0.066 – 4.0 nm−1. To ensure statistically significant data, at least 106 counts were collected for each sample, resulting in an analysis time of between 4 and 12 h. The spectra were calibrated with silver behenate, which has a lamellar periodicity of 5.84 nm84 and angularly integrated by using the software SAXGUI (v2.02.09).

Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS)

SANS measurements were performed using the CG-3 Bio-SANS instrument at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN. The incident neutron wavelength was 0.6 nm, with a spread in wavelength, Δλ/λ, of 15 %. Data were recorded at a range of sample-to-detector distances to provide a q range from 0.03 – 3.2 nm−1. To ensure statistically significant data, at least 106 counts were collected for each sample at each detector distance. The samples were contained in quartz cells with a 2 mm path length and placed in a sample chamber held at 25.0 ± 0.1 °C. The data were corrected for detector efficiency, background radiation, empty cell scattering, and incoherent scattering to determine the intensity on an absolute scale.58 The background scattering from the solvent was subtracted. Samples of reduced BFDMA in 1 mM Li2SO4 with increasing levels of DOPE (φDOPE = 0 to 1) were characterized. The processing of data was performed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) with additional Igor Pro user procedures provided by ORNL. Guinier analysis and comparisons to previously published results58 were used to interpret the scattering data.

Results and discussion

Influence of DOPE on the transfection efficiency of lipoplexes containing reduced BFDMA (BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA)

In the text below we use the abbreviations, BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA and BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA to describe the mixed-lipid-containing lipoplexes. The subscript “RED” refers to the reduced state of BFDMA and “OX” refers to the oxidized state of BFDMA. In addition, we define φDOPE to be the mole fraction of DOPE in lipoplexes formed from DOPE and BFDMA [φDOPE = moles of DOPE/(moles of DOPE + moles of BFDMA)]. Because we used measurements of the transfection of cells to identify lipid compositions (values of φDOPE) for detailed characterization by SAXS and SANS, below we present first the results of our transfection studies, and follow those results by descriptions of nanostructural characterization of the lipoplexes of highest interest.

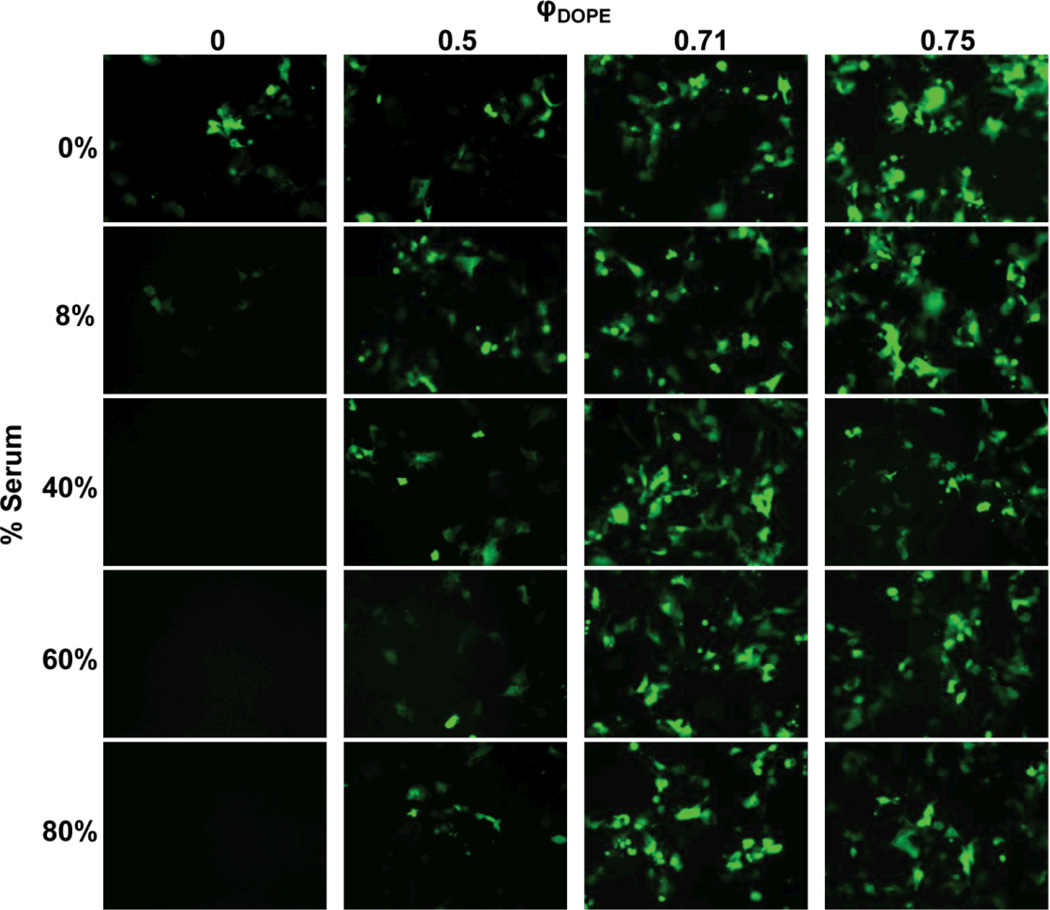

To determine the ability of lipoplexes formed from mixtures of reduced BFDMA and DOPE to transfect cells in both serum-free and serum-containing cell culture media, we designed a series of qualitative gene expression experiments using the COS-7 mammalian cell line and a plasmid DNA reporter gene construct (pEGFP-N1) encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). For these experiments, lipoplexes prepared at four different molar ratios of BFDMA to DOPE (φDOPE = 0, 0.5, 0.71 and 0.75; as described below, these compositions were selected to provide ratios above and below a maximum in cell transfection efficiency that was observed in initial experiments) were added to cells cultured in media containing a broad range of different concentrations (from 0 to 80%) of bovine serum (BS). For all φDOPE and BS levels tested, the final concentration of BFDMA in each well was 8 µM and the final concentration of DNA was 2.4 µg/ml. These concentrations of BFDMA and DNA were selected to enable comparison to our past studies on the characterization of BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes.55–58, 61 The cells were incubated with lipoplexes in media containing various concentrations of BS for 4 h, followed by incubation in fresh growth medium containing 10% BS (see “Materials and Methods” for a detailed description of this assay) for an additional 44 h.

Fig. 2 shows representative fluorescence micrographs of cells 48 h after exposure to the lipoplexes. These data demonstrate that lipoplexes containing BFDMA/DNA only were able to transfect cells growing in serum-free culture media (Fig. 2, φDOPE = 0; 0% BS), as indicated by the presence of cells expressing EGFP. Further inspection of these data, however, reveals that these BFDMA/DNA-only lipoplexes (φDOPE = 0) mediated qualitatively lower levels of transgene expression in media containing 8% serum, and that at higher levels of serum (e.g., from 40% to 80% BS) no visible indication of transgene expression was observed (e.g., absence of cells expressing visible levels of EGFP expression in the lower left column of Fig. 2). These results confirm those of our past studies,55–57, 60 indicating that serum proteins have a deleterious effect on transfection of cells with BFDMA.

Fig. 2.

Influence of serum on EGFP expression in COS-7 cells treated with lipoplexes formed from pEGFP-N1 and mixtures of reduced BFDMA and DOPE for 4 h. The media used was pure OptiMEM or a mixture of OptiMEM and BS. All experiments were performed by adding 50 µL of lipid/DNA mixture in 1 mM Li2SO4 solution to 200 µL of media in the presence of cells. Final BS concentrations are given down the left hand side of the figure. The overall concentrations of BFDMA and DNA in each lipoplex solution were 8 µM and 2.4 µg/ml, respectively, providing a charge ratio of 1.1:1 (+/−) for all samples as DOPE has a net charge of zero. Mole fractions of DOPE, φDOPE = DOPE/(BFDMA+DOPE), are given across the top of the figure. Fluorescence micrographs (1194 µm by 895 µm) were acquired 48 h after exposure of cells to lipoplexes.

Further inspection of Fig. 2, however, reveals that incorporation of DOPE into lipoplexes with BFDMA leads to qualitatively large increases in the extent of cell transfection when serum is present (φDOPE > 0; columns 2, 3 and 4). In particular, we note that lipoplexes with φDOPE = 0.71 and 0.75 mediated significant levels of transfection in cells growing in media containing up to 80% BS (see images in the lower right section of Fig. 2). Overall, these results demonstrate that the addition of DOPE to BFDMA results in lipoplexes that promote high levels of cell transfection in the presence of serum.

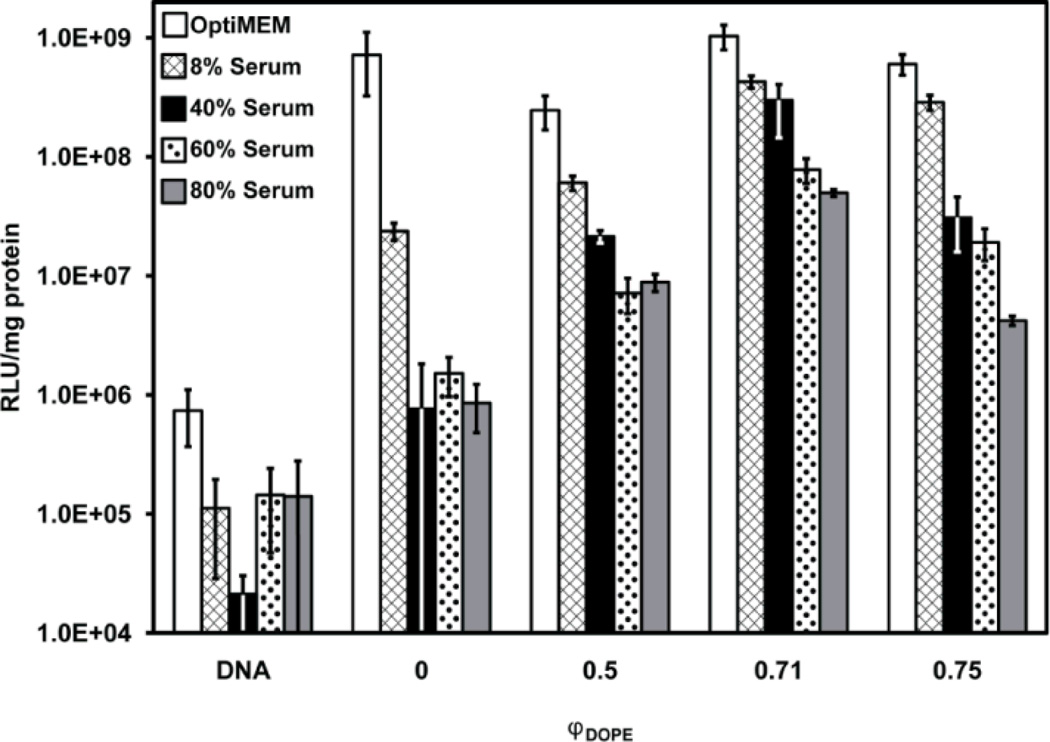

To quantify the differences in gene expression observed in Fig. 2 using lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE, we conducted transfection experiments using lipoplexes formed using a plasmid DNA construct (pCMV-Luc) encoding firefly luciferase (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Influence of serum on normalized luciferase expression in COS-7 cells treated with lipoplexes formed from pCMV-Luc and mixtures of reduced BFDMA and DOPE for 4 h. The final concentration of BS is given in the legend. DNA was present at a concentration of 2.4 µg/ml for all samples. “DNA” denotes a control with DNA only (no lipid). Molar fractions of DOPE, φDOPE = DOPE/(BFDMA+DOPE), are given on the x-axis for each sample. The concentration of BFDMA in each sample was 8 µM. Luciferase expression was measured 48 h after exposure to lipoplexes. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

From the results shown in Fig. 3, we make the following three observations. First, in serum-free cell culture medium (white bars), lipoplexes prepared with φDOPE ranging from 0.5 to 0.75 do not seem to differ significantly from lipoplexes of BFDMA/DNA only (φDOPE =0) in their ability to efficiently transfect cells (all DOPE-containing transgene expression measurements have a mean within one standard deviation of lipoplexes of BFDMA/DNA). Second, in serum-containing cell culture media (all non-white bars in Fig. 3), the efficiency of cell transfection does depend widely on the ratio of BFDMA to DOPE and on the concentration of BS present during transfection. For example, comparing changes in φDOPE, when the cell culture medium was supplemented with 80% BS (gray bars in Fig. 3), cell transfection was measured to be significantly lower when DOPE is absent from the lipoplexes than when DOPE was present in the lipoplexes (e.g. protein expression was 8.6 ± 3.7 × 105 RLU/mg protein at φDOPE = 0 and 5.0 ± 0.4 × 107 RLU/mg protein at φDOPE = 0.71). Thus, we conclude that incorporation of DOPE into lipoplexes of BFDMA can increase levels of transgene expression by almost two orders of magnitude in serum-containing media.

The third and final observation regarding the results in Fig. 3 is that the level of transgene expression goes through an apparent maximum as a function of φDOPE for all levels of serum present during cell transfection. This maximum occurs around a ratio of φDOPE = 0.71. We also note here that when cells are treated with DOPE/DNA in the absence of BFDMA, low levels of transfection result (Fig. S1† and S2†) and, thus, the decrease in transfection efficiency observed at the highest values of φDOPE could reflect the dominating influence of DOPE in these DOPE-rich complexes. Overall, from the results shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, we conclude that inclusion of DOPE in BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes leads to compositions that are able to promote significant levels of transgene expression in the presence of high and physiologically relevant concentrations of serum.

Influence of DOPE on the physical properties and nanostructure of lipoplexes containing reduced BFDMA (BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA)

Past studies have demonstrated that, amongst a large number of factors that influence the ability of lipoplexes formed from cationic lipids to transfect cells, the size, zeta potential and nanostructure of the lipoplexes can be important.64, 85 Fig. S3†–S6† (see ESI) show measurements of the sizes of BFDMA-containing lipoplexes under a range of conditions (obtained using DLS). With reference to the summary of key data presented in Fig. S3†, we make two observations. First, inspection of Fig. S3A† and S3B† reveals that incorporation of DOPE into BFDMA lipoplexes in the absence of serum causes the intensity-weighted size distributions of the lipoplexes to increase from ~680 ± 280 nm to ~2900 ± 2000 nm (the corresponding number-weighted size distributions are ~420 ± 120 nm to ~750 ± 300 nm, respectively). These broad size distributions are typical of lipoplexes formed by cationic lipids and DNA, and they include a range of sizes of lipoplexes that are taken up by cells. Second, as evidenced by results shown in Fig. S3C†, interpretation of DLS data obtained in the presence of serum is complicated because serum (without lipoplexes) contains a range of aggregates with sizes of ~80 nm ± 20 nm (intensity-weighted). A comparison of Fig. S3C† with either Fig. S3D† or S3E†, however, reveals that, in the presence of serum, the size distributions of BFDMA lipoplexes with and without DOPE exhibit a broad peak around ~1 µm that is absent in the sample of serum only. In addition, comparison of DLS data measured after 20 minutes and 4 hours of incubation of the lipoplexes revealed no significant change in size, suggesting that DOPE does not lead to a change in colloidal stability (see ESI Fig. S4†–S6†). We also measured zeta potentials of BFDMA lipoplexes containing DOPE (see ESI Fig. S3† and S7†). Although we measured the presence of DOPE to change the zeta potentials of lipoplexes of BFDMA in the absence of serum, when serum was present, the zeta potentials of the lipoplexes were not measured to change significantly with addition of DOPE. Overall, our results obtained using DLS and zeta potential measurements indicate that, in the presence of serum, addition of DOPE to the lipoplexes of BFDMA causes a small increase in average size within a broad size distribution and no significant change in surface charge. We conclude, therefore, that the effect of DOPE on the size and charge of the lipopexes is unlikely to be the origin of the influence of DOPE on transfection efficiency.

To determine how the presence of DOPE influences the nanostructure of lipoplexes formed by BFDMARED and DNA, and to determine whether the presence of serum impacts any nanostructures that do form, we next performed a series of SAXS and SANS experiments. In these experiments, pGFP-N1 DNA was used at a CR of 1.1:1 with BFDMARED, similar to the lipoplexes used in the cell transfection experiments described above.

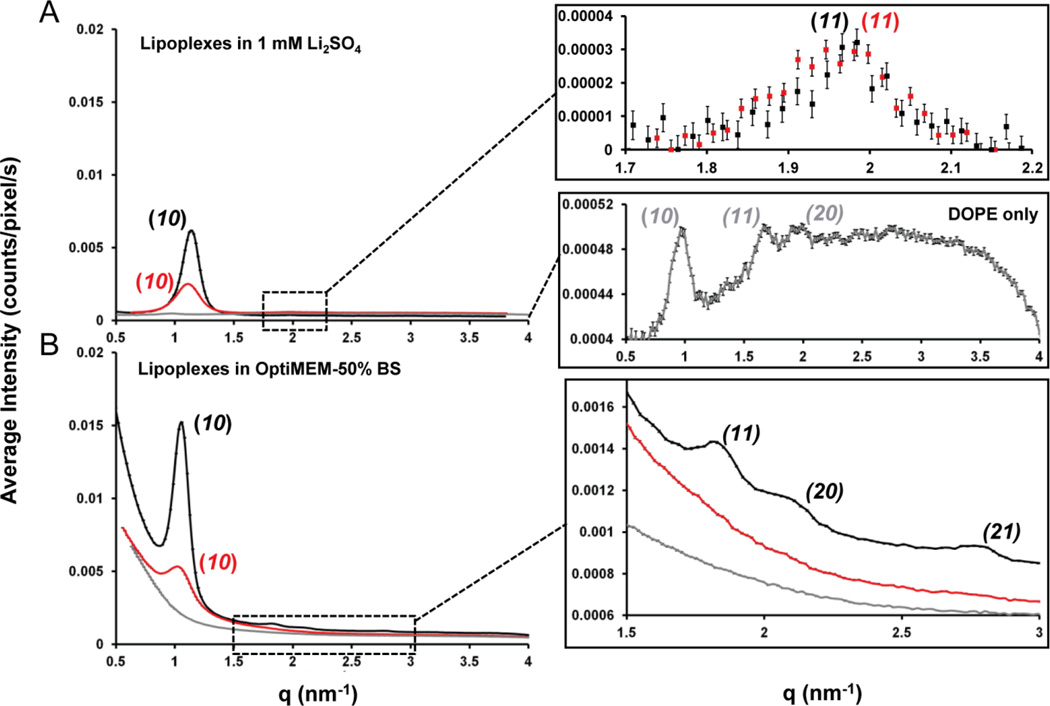

The goal of our first scattering experiment was to use SAXS to characterize the impact of DOPE on the nanostructures of lipoplexes containing BFDMARED in a simple electrolyte solution (1 mM Li2SO4). For BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA lipoplexes at φDOPE = 0.71 (Fig. 4A, black data), Bragg peaks at q10 = 1.12 nm−1 and q11 = 1.97 nm−1 are observed, corresponding to a ratio q10/q11 = √3 and thus a HIIc nanostructure (hexagonal structures are characterized by a qx/q10 spacing ratio of 1:√3:√4:√7).86 As shown in Fig. 1D, the periodicities of the 2D hexagonal structure are characterized by the unit cell spacing, a = 4π/[(√3)q10] = 6.48 ± 0.13 nm in addition to the same d-spacing parameter described above, d = 2π/q10 or (√3/2)a = 5.61 ± 0.11 nm.71 We note here that, although one recent study has shown lipid-DNA mixtures can form cubic nanostructures,87 we conclude that the nanostructures formed by DOPE, BFDMARED and DNA are not cubic because (i) all samples observed between crossed-polars are birefringent whereas cubic phases are optically isotropic (Fig. S8†), and (ii) the Bragg peak spacings for cubic phases are inconsistent with our SAXS data (see ESI for additional discussion). In contrast to lipoplexes formed by DOPE, BFDMARED and DNA, the scattering spectra of BFDMARED based lipoplexes without DOPE (as shown in ESI Fig. S9A†, black data) exhibited Bragg peaks at q001 = 1.27 nm−1 and q002 = 2.54 nm−1, corresponding to a ratio q002/q001 = 2 and, therefore, a Lαc nanostructure (lamellar structures are characterized by a qx/q001 spacing ratio of 1:2:3:4).86 The d-spacing periodicity (Fig. 1C) was calculated as d = 2π/q001 = 4.95 ± 0.1 nm.58

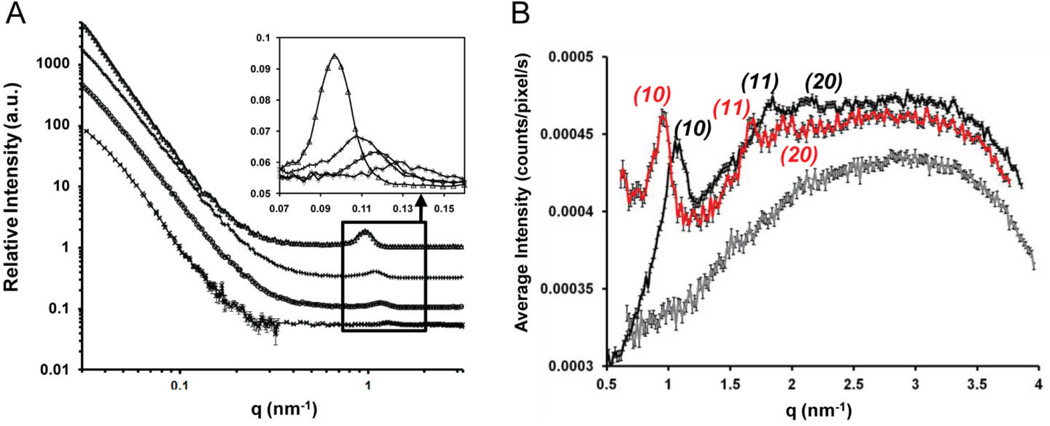

Fig. 4.

SAXS spectra obtained using BFDMARED−DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71) (black), BFDMAOX-DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71) (red) or DOPE only (grey) containing lipoplexes in; (A) 1 mM Li2SO4, using lipid concentrations of 0.87 mM BFDMA and/or 2.17 mM DOPE; (B) OptiMEM with 50% (v/v) BS, using diluted lipid concentrations of 0.32 mM BFDMA and/or 0.8 mM DOPE; all in the presence of pEGFP-N1 (2.0 mg/ml) at a charge ratio of 1.1:1 or 3.3:1 (+/−) for reduced or oxidized BFDMA containing solutions respectively. Inserts for both graphs are given on the right hand side. Bragg peaks are indicated on the graphs and color coded to their respective lipoplex.

We conclude, therefore, that the inclusion of DOPE in lipoplexes of BFDMARED (at φDOPE = 0.71) causes the nanostructure of the lipoplexes to change from Lαc to HIIc (see Table 1 for a summary of these scattering results). We note here that lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE with φDOPE = 0.71 possess a total lipid:DNA molar ratio of 3.9:1. In our past studies,58 we observed lipoplexes of BFDMARED only, with lipid:DNA molar ratios as high as 4:1, to possess a multilamellar nanostructure. The 2D hexagonal nanostructure reported above in the presence of DOPE is not, therefore, simply a result of a high total lipid:DNA molar ratio within the lipoplex, but rather, it reflects the tendency of DOPE to promote formation of inverse hexagonal nanostructure. The observation that DOPE induces formation of the HIIc nanostructure with BFDMA is consistent with several past studies that have reported on the influence of DOPE on some (non-redox-active) cationic lipid formulations.63, 68–73 Furthermore, in light of the above-described transfection results, indicating that lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE lead to high levels of transfection in the presence of serum, the formation of the HIIc phase in solution in the presence of DNA is potentially significant as the HIIc nanostructure is thought to facilitate fusion of lipoplexes and cell membranes.72, 74–76

Table 1.

SAXS results; Bragg peak qhkl positions (using Miller Indices), d-spacing and Bragg peak ratios, nanostructure, and unit cell spacing (a) for HIIc phases, for lipoplexes of reduced or oxidized BFDMA/pGFP (φDOPE = 0) and reduced or oxidized BFDMA-DOPE/pGFP (φDOPE=0.71) with and without the presence of OptiMEM and 50% BS (v/v), and lipids of reduced BFDMA, reduced BFDMA-DOPE and DOPE. Errors are based on equipment calibration of 2% using a silver behenate standard.

| Lipoplex | Bragg peak qhkl position (nm−1) | Bragg peak ratios | Nano- structure |

d or aa (nm) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st peak | 2nd peak | 3rd peak | 4th peak | 2nd/1st | 3rd/1st | 4th/1st | |||

| Lipoplexes in 1 mM Li2SO4 | |||||||||

| BFDMARED/pGFP | q001 = 1.27 | q002 = 2.53 | - | - | 1.99 | - | - | Lαc | 4.95 ± 0.10 |

| BFDMARED-DOPE/pGFP | q10 = 1.12 | q11 = 1.97 | - | - | 1.76 | - | - | HIIc | 6.48 ± 0.13 |

| BFDMAOX/pGFP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| BFDMAOX DOPE/pGFP | q10 = 1.12 | q11 = 1.97 | - | - | 1.76 | - | - | HIIc | 6.48 ± 0.13 |

| DOPE/pGFP | q10 = 0.95 | q11 = 1.67 | q20 = 1.92 | - | 1.75 | 2.00 | - | HIIc | 7.63 ± 0.15 |

| Lipoplexes in OptiMEM and 50% v/v BS | |||||||||

| BFDMARED/pGFP | q001= 1.13 | q002 = 2.25 | - | - | 1.99 | - | - | Lαc | 5.56 ± 0.11 |

| BFDMARED-DOPE/pGFP | q10 = 1.04 | q11 = 1.79 | q20 = 2.08 | q21 = 2.77 | 1.72 | 2.00 | 2.66 | HIIc | 6.97 ± 0.14 |

| BFDMAOX/pGFP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| BFDMAOX-DOPE/pGFP | q10 = 1.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.04 ± 0.12 |

| DOPE/pGFP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lipids only in 1 mM Li2SO4 | |||||||||

| BFDMARED | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| BFDMARED-DOPE | q10 = 1.05 | q11 = 1.81 | q20 = 2.12 | - | 1.72 | 2.02 | - | HII | 6.91 ± 0.14 |

| DOPE | q10 = 0.95 | q11 = 1.69 | q20 = 1.91 | - | 1.78 | 2.01 | - | HII | 7.63 ± 0.15 |

d-spacing, d given for lamellar Lα structure, a=2/√3d given for hexagonal HII structure (See Fig. 1C and 1D).

To provide further insight into the nanostructure of the lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and DOPE, including the influence of serum on the nanostructure, we performed several additional experiments. First, we investigated the extent of mixing of the DOPE and BFDMA within the lipoplex formulations. To this end, we determined the periodicity of the nanostructures formed by mixtures of BFDMA and DOPE with compositions of φDOPE = 0, 0.28, 0.5 and 1.0 to assess if a single periodicity corresponding to well-mixed lipoplexes was present (demixing of BFDMA and DOPE would be evidenced by multiple periodicities). SANS was used for these measurements to enable direct comparison to our past SANS studies of lipoplexes formed using BFDMA/DNA only (φDOPE = 0).58 All samples were prepared in 1 mM Li2SO4 using 100% D2O. The results are shown in Fig. 5A. Inspection of Fig. 5A shows that only one Bragg peak is observed in each SANS spectrum, and that the location of each Bragg peak, and thus the corresponding periodicity, is dependent on the amount of DOPE in the sample. The measured periodicity ranges from d = 4.95 ± 0.10 nm for lipoplexes of BFDMARED only (in agreement with SAXS analysis in Fig. 4A and Table 1, as well as the results of past SANS studies),58, 61 increases with the incorporation of DOPE into the lipoplexes, and reaches d = 6.50 ± 0.13 nm or a = (2/√3)d = 7.51 ± 0.15 nm (both values are in close agreement with past SAXS studies)71, 88 for solutions of DOPE/DNA only (in agreement with the SAXS result above, Fig. 4A grey data). We note that past studies have reported that DOPE forms a HII phase in the absence of DNA, and that in the presence of DNA there is little measurable association of the DNA and lipid.71 This general result is consistent with our SANS measurements and transfection results shown in Fig. S1† and Fig. S2† in which levels of transfection mediated by mixtures of DOPE and DNA are comparable to those mediated by naked DNA (see also Fig. 5B below). The key conclusion extracted from the appearance of a single Bragg peak in each of the scattering spectra is that DOPE is intimately mixed with BFDMA within the lipoplexes, and that increasing the relative amount of DOPE present in the lipoplex progressively increases the periodicity of the lipid-DNA complex. Thus we conclude that the transfection results obtained with mixtures of BFDMA and DOPE are likely the result of the activity of lipoplexes comprised of both BFDMA and DOPE (and not, for example, lipoplexes comprised predominantly of only one of the lipids in the formulation).

Fig. 5.

Evidence of association of BFDMA and DOPE in solution in the presence and absence of DNA; (A) SANS spectra measured using solutions of; (Δ) 1 mM DOPE (φDOPE = 1); (+) 1 mM BFDMA and 1 mM DOPE (φDOPE = 0.5); (o) 1 mM BFDMA and 0.4 mM DOPE (φDOPE = 0.28), (x) 1 mM BFDMA (φDOPE = 0), all in the presence of DNA (2.9 mg/ml) and, when BFDMA is present, at a charge ratio of 1.1:1 (+/−). The data are offset for clarity. The insert shows an expanded view of the Bragg peaks and has no offset in intensity between samples. (B) SAXS spectra obtained using lipid only solutions of; 1 mM BFDMA (grey); 2.5 mM DOPE (red); 1 mM BFDMA, 2.5 mM DOPE (black); all in 1 mM Li2SO4 (grey).

The results presented above indicate that the nanostructure of lipoplexes formed by BFDMA and DOPE is HIIc. To determine if the presence of DNA is required to form the HIIc phase, we used SAXS to characterize the nanostructure of DNA-free complexes containing BFDMA and DOPE (and also those free of DOPE). Inspection of Fig. 5B reveals that complexes formed from BFDMARED-DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71, black data) and DOPE only (red data) both show Bragg peaks with 1:√3:√4 spacing, consistent with HII nanostructure, with a positive shift in q10 of 0.13 nm−1 on incorporation of BFDMARED. In contrast, BFDMARED shows no Bragg peaks in the scattering (grey data). Together, these results indicate that formation of the inverse hexagonal structure, which we observe to correlate with the presence of high levels of transfection in the presence of serum proteins, is driven by the presence of the DOPE. Specifically, we observe DOPE and BFDMA to mix in the absence of DNA to form the inverse hexagonal nanostructure.

The scattering results described above were obtained using simple electrolyte solutions. In a final set of scattering experiments, we investigated the influence of cell culture media and the presence of serum on the nanostructures of lipoplexes containing BFDMARED (φDOPE = 0), BFDMARED with DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71) and DOPE only (φDOPE = 1). Lipoplexes of BFDMA only (φDOPE = 0, see ESI Fig. S9B†, red data) were prepared in Li2SO4, and then diluted by the addition of OptiMEM and then 50% (v/v) BS. This dilution resulted in a 2.7-fold reduction of the concentration of lipid and DNA in solution. Our past studies58 and the studies of others71 have revealed, however, that such dilution does not typically affect the type of nanostructure observed in solution. For these samples, we observed Bragg peaks at q001 = 1.13 nm−1 and q002 = 2.25 nm−1, corresponding to a Lαc nanostructure (see Table 1 for periodicities). In contrast, as shown in Fig. 4B (black data), the SAXS spectrum obtained using lipoplexes with φDOPE = 0.71 (in 50% BS) exhibit four Bragg peaks: q10 = 1.04 nm−1, q11 = 1.79 nm−1, q20 = 2.08 nm−1, and q21 = 2.77 nm−1. The ratios of qhk/q10 correspond to √3, √4 and √7, thus demonstrating that incorporation of DOPE into lipoplexes formed from DNA in the presence of 50% BS also causes the nanostructure of the lipoplexes to change from Lαc (without DOPE) to HIIc (with DOPE).

A comparison of Fig. S9A† and S9B† with Fig. 5A and 5B provides additional insight into the influence of cell culture media and serum proteins on the nanostructures of these lipoplexes. Addition of serum to either BFDMARED only or BFDMARED-DOPE lipoplexes caused the Bragg peaks to move to lower q, corresponding to an increase in periodicity of 0.5–0.7 nm (shown for q001 in Fig. S9A† and S9B† by a vertical dotted line at q001, Fig. S9B†). This result indicates that the presence of serum causes the periodicity of the nanostructures (Fig. 1C and 1D) to increase by 8–12%. This increase in periodicity has been seen in at least one other study (i.e., on lipoplexes of DC-Cholesterol, DOPE and DNA),64 where it was hypothesized that cationic lipids within lipoplexes containing DOPE associate with proteins89 leading to the increased periodicity.66, 67 Here we note that the key conclusion extracted from our SAXS measurements is that the hexagonal nanostructure of the lipoplexes of DOPE and BFDMA survives exposure to high concentrations of serum proteins. This result is consistent with our measurement of high levels of transfection of cells in the presence of serum when using lipoplexes formed from mixtures of DOPE and BFDMA.

Here we also note that a number of past studies have reported that serum proteins can promote the disassembly of lipoplexes comprised of DNA and cationic lipids.60, 66, 90 These studies have also suggested that the destruction of the lipoplexes by serum proteins underlies the low levels of cell transfection measured in the presence of serum. In particular, in a study reported recently, cryo-TEM was used to characterize the nanostructures of BFDMA-containing lipoplexes (no DOPE) in the presence of serum and revealed that serum can promote dissociation of lipoplexes containing BFDMA.60 Our SAXS-based characterization of the nanostructures of lipoplexes of BFDMARED performed in the presence of serum (Fig. S9B†) suggests that addition of serum does not cause complete loss of the Lαc nanostructure of the BFDMARED lipoplex. This result appears consistent with these prior cryo-TEM results,60 which indicated that some intact multilamellar, Lαc nanostructures also appeared to survive addition of serum under certain conditions. The results shown in Fig. S9B† which reveal that the periodicity of the multilamellar nanostructure changes upon addition of serum, also suggests an alteration of the physicochemical properties of the lipoplexes induced by association of proteins, rather than wholesale destruction and unraveling of the lipoplexes, which could also contribute to the lower levels of transfection promoted by lipoplexes formed using BFDMA/DNA only in the presence of serum.

Influence of oxidation state of BFDMA on the transfection efficiency, physical properties, and nanostructure of lipoplexes containing BFDMA and DOPE

The key issue that we addressed next is whether the oxidation state of BFDMA influences the transfection efficiency of lipoplexes containing DOPE. Although our past studies using lipoplexes of BFDMA alone have revealed that the oxidation state of the BFDMA has a pronounced effect on transfection, because the nanostructures of lipoplexes formed by BFDMA only (multilamellar) and mixtures of DOPE and BFDMA (inverse hexagonal, see above) are different, we emphasize that it is not possible to anticipate the effects of changes in the oxidation state of BFDMA on the transfection efficiency of lipoplexes containing BFDMA and DOPE on the basis of our past results using lipoplexes containing BFDMA only.

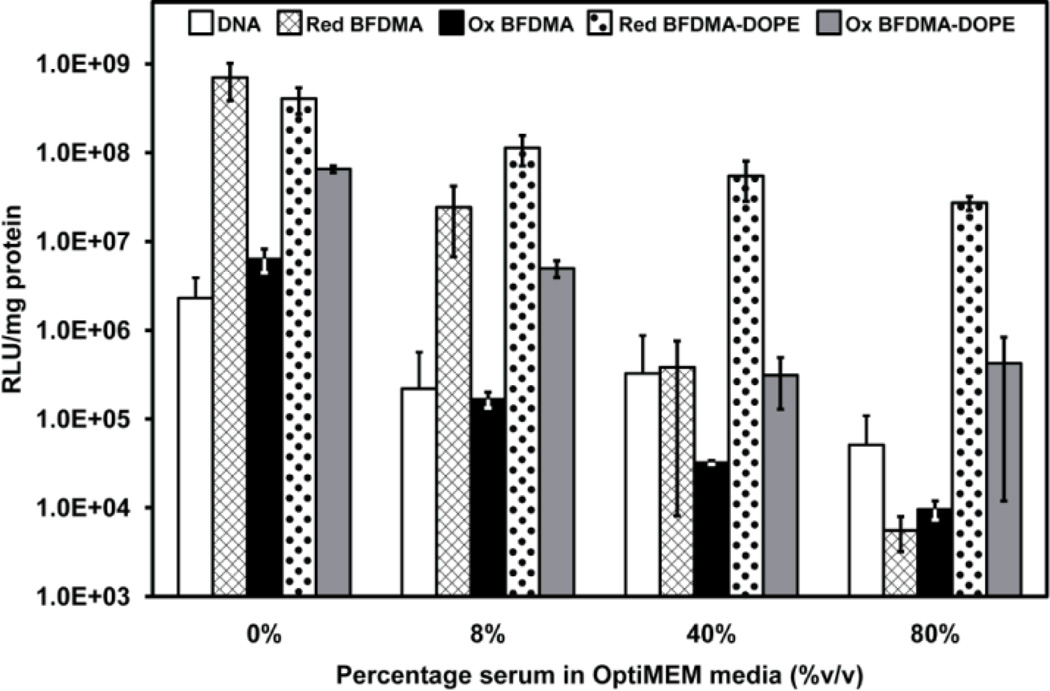

To enable studies of the effect of the oxidation state of BFDMA on the transfection efficiency and nanostructure of lipoplexes containing mixtures of BFDMA and DOPE, we first demonstrated that it was possible to oxidize BFDMA in the presence of DOPE (as shown in ESI, Fig. S10†). Fig. 6 presents the results of a quantitative gene expression assay, again using lipoplexes formed using the pCMV-Luc plasmid DNA construct, and shows the effects of oxidized BFDMA on cell transfection (both in the absence and presence of DOPE and as a function of the concentration of serum). Guided by the results presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, the lipoplexes used in these experiments were prepared with φDOPE = 0.71 (dotted and grey bars in Fig. 6). Inspection of Fig. 6 leads to two key observations. First, in the absence of serum (0% column), the levels of transgene expression mediated by lipoplexes formed using BFDMAOX/DNA were approximately two orders of magnitude lower than levels mediated by lipoplexes formed using BFDMARED/DNA (e.g., compare hashed bar to black bar). These differences were maintained, but were smaller (by approximately one order of magnitude), for DOPE-containing lipoplexes formed using reduced or oxidized BFDMA (compare dotted bar to grey bar). Second, when the cell culture medium contained 40% or 80% BS (Fig. 6), relative to the high levels of cell transfection achieved using lipoplexes containing DOPE and reduced BFDMA (dotted bars, consistent with results in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3), the levels of transgene expression decreased by at least two orders of magnitude when using lipoplexes formed from oxidized BFDMA and DOPE (compare dotted bars to grey bars). In particular, when we compare these two observations, we conclude that control of the oxidation state of BFDMA in lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE leads to larger changes in transfection efficiency in the presence of high concentrations of serum than in the absence of serum. Furthermore, inspection of Fig. 6 reveals that transfection mediated by BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA in the presence of 80% BS is more than two orders of magnitude lower than levels mediated by BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA in the absence of serum. This result suggests that the presence of serum proteins may lead to substantial changes the structure and/or properties of lipoplexes of DOPE and oxidized BFDMA in ways that influence their activities, a point that we return to below.60

Fig. 6.

Influence of serum on the normalized luciferase expression in COS-7 cells treated with naked DNA (white bars), and lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA (hashed bars), oxidized BFDMA (black bars), reduced BFDMA and DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71, dotted bars), and oxidized BFDMA and DOPE (φDOPE = 0.71, gray bars) for 4 h. All experiments were performed by adding 50 µL of DNA/lipid mixture in 1 mM Li2SO4 solution to 200 µL media in the presence of cells. The media was pure OptiMEM or a mixture of OptiMEM and BS. The final concentration of BS is indicated along the x-axis. DNA was present at a concentration of 2.4 µg/ml in the presence of cells for all samples. 8 µM BFDMA was present in each BFDMA containing sample. Luciferase expression was measured 48 h after exposure to lipoplexes. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

We note here that we also confirmed the above conclusions regarding the impact of the oxidation state of BFDMA in the presence of DOPE on cell transfection by using qualitative fluorescence micrographs of cells expressing EGFP from experients using lipoplexes formed from pGFP-N1 (as shown in ESI Fig. S11†). The results of additional live/dead cytotoxicity assays revealed that the lipoplex compositions described above do not lead to substantial cytotoxicity under the conditions used in the above experiments. Additional data and details of these cytotoxicity screens are included in ESI, Fig. S12† and Table S1†.

To provide insight into the origin of the above-described influence of the oxidation state of BFDMA on the transfection efficiency of lipoplexes containing BFDMA and DOPE in the presence of serum, we measured the impact of changes in oxidation state of BFDMA on the sizes and zeta potentials of the lipoplexes (see ESI Fig. S3E† and S3F†). Inspection of this data reveals that changes in the oxidation state of the BFDMA leads to no significant change in zeta potential but a decrease in the number of aggregates with sizes of ~1 µm (i.e., sizes of aggregates of reduced BFDMA). We also performed SAXS measurements to determine if the oxidation state of BFDMA within the lipoplexes causes a change in nanostructure. Prior to performing these measurements, we confirmed that the scattering spectra of lipoplexes of BFDMAOX (no DOPE; see ESI Fig. S9A†, red data) did not exhibit Bragg peaks (consistent with prior reports based on use of SANS and cryo-TEM58 which show the absence of ordered lamellar structure within BFDMAOX/DNA aggregates). For lipoplexes of BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA dispersed in Li2SO4 (φDOPE = 0.7, Fig. 4A, red data), Bragg peaks at q10 = 1.12 nm−1 and q11 = 1.98 nm−1 are observed, i.e. Bragg peaks at the same position as the lipoplex containing reduced BFDMA and DOPE (Fig. 4A, black data), again, corresponding to a ratio q10/q11 = √3 and thus a HIIc nanostructure. However, the intensity of the q10 peak for the BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA sample is only 40% of the q10 peak for the BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA sample. This suggests that the fraction of the BFDMA and DOPE in the HIIc nanostructural state is lower for the samples containing oxidized BFDMA and DOPE as compared to lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and DOPE. Here we also note that DOPE/DNA mixtures (no BFDMA) were characterized by SAXS (Fig. 4A, grey data). Even though three Bragg peaks are seen in the scattering at a 1: √3: √4 periodicity indicating HII nanostructure, shown in the insert of Fig. 4A, the overall intensity of scattering from DOPE is significantly lower than BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA. This suggests that the Bragg peaks seen for the BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA data (Fig. 4A, red data) do not arise from the presence of DOPE alone and that BFDMAOX must be integral to the BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA complex. Overall, the results presented above, when combined with our transfection measurements, serve to emphasize the correlation between the presence of HIIc nanostructures in solution and the transfection efficiency of the BFDMA-DOPE lipoplexes.

We also investigated the influence of serum proteins on the nanostructure of the lipoplexes comprised of oxidized BFDMA and DOPE. Similar to the scattering data obtained using lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA and DOPE in Li2SO4 (Fig. 4A), BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA in 50% BS (Fig. 4B, red data) generated a scattering spectrum with a first Bragg Peak at q = 1.04 but with only 18% of the intensity as BFDMARED-DOPE/DNA in 50% BS, (Fig. 4B, black data). DOPE/DNA mixtures in 50% BS were also subjected to SAXS (Fig. 4B, grey data). No Bragg peaks are seen in the scattering. Because the intensity of scattering for serum containing samples at q < 1 nm−1 is an order of magnitude higher than the Bragg peaks seen for DOPE/DNA in Li2SO4 (Fig. 4A, grey data), any Bragg peaks generated by the DOPE lipid in this mixture are likely masked by the presence of serum. The Bragg peaks seen for the BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA data (Fig. 4A, red data) suggests that the lipoplex nanostructure giving rise to the Bragg peaks cannot be attributed to the presence of DOPE alone and that BFDMAOX must be helping the BFDMAOX-DOPE/DNA complex to associate in a similar mechanism as for Li2SO4 based lipoplexes discussed above. Overall, the above result is significant because it reveals that the correlation between the presence of HIIc nanostructures in solution and the transfection efficiency of the BFDMA-DOPE lipoplexes is preserved in the presence of high concentrations of serum proteins.

Conclusions

A key result reported in this paper is that incorporation of DOPE into BFDMA-containing lipoplexes leads to a substantial increase in cell transfection efficiency in the presence of high concentrations of serum (up to 80% BS). This observation appears closely correlated with nanostructural characterization presented in this paper, which clearly shows that the incorporation of DOPE into the lipoplexes induces the formation of a HIIc nanostructure. Although additional studies will be required to elucidate the precise mechanism of transfer of our DOPE-containing lipoplexes into cells, past studies have established that lipoplexes with a HIIc nanostructure exhibit an increased propensity to fuse with cell membranes63, 68, 72, 74–76 (thus leading to a mechanism of uptake that is not generally thought to occur with lipoplexes that possess Lαc nanostructures). It appears likely, therefore, that the high levels of cell transfection that we observe using lipoplexes of DOPE and BFDMARED in the presence of serum is the result of fusion of these lipoplexes with the cell membranes.

A second key result presented in this paper is that a change in the oxidation state of the BFDMA that is used to form the lipoplexes with DOPE substantially alters the efficiency with which lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE transfect cells (over a wide range of serum levels tested). When BFDMA is reduced, lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE are highly efficient in transfecting cells. In contrast, when BFDMA is oxidized, lipoplexes of BFDMA and DOPE lead to levels of transgene expression that are two orders of magnitude lower than for lipoplexes containing reduced BFDMA. Complementary measurements using SAXS reveal that the low transfection efficiency of the lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA and DOPE correlates with the presence of weak Bragg peaks corresponding to the HIIc nanostructure and thus a low amount of this nanostructure in the solution. Our measurements of changes in physical properties of these lipoplexes (sizes, zeta-potentials and colloidal stability), as caused by incorporation of DOPE or oxidation of BFDMA, do not provide an alternative account for the influence of these key variables on the transfection efficiencies that are reported in this paper. We interpret our results to provide support for our hypothesis that DOPE-induced formation of the HIIc nanostructure of the BFDMA-containing lipoplexes underlies the high cell transfection efficiency measured in the presence of serum, and that the oxidation state of BFDMA within lipoplexes with DOPE substantially regulates the formation of the HIIc nanostructure and thus the ability of the lipoplexes to transfect cells with DNA.

Overall, the results described herein represent an important step toward the development of redox-active lipid materials that permit spatial and/or temporal control over the transfection of cells (e.g., by the application of externally-applied electrochemical potentials or the spatially controlled delivery of chemical reducing agents). We conclude by noting that a major goal of synthetic DNA delivery vector research is to develop gene delivery materials that function in physiologically relevant environments (e.g., in the presence of high serum concentrations). A second major goal is to be able to achieve facile control over the location and timing of the delivery of DNA. The results reported in this paper represent a significant step toward the realization of gene delivery materials that possesses attributes that are relevant to both of these goals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (1 R21 EB006168 and AI092004), the National Science Foundation (CBET-0754921 and DMR-1121288) and the ARO (W911NF-11-1-0251). We acknowledge the support of Oak Ridge National Laboratory in providing the neutron facilities used in this work. We thank C. Jewell and X. Liu for many helpful discussions, S. Hata and H. Takahashi for assistance with synthesis of BFDMA, and V. Urban and D. Savage for help with the SANS and SAXS measurements, respectively.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Results of additional experiments including cell transfection and toxicity measurements of control samples, size and zeta-potential data, optical micrographs of BFDMA/DNA and BFDMA-DOPE/DNA lipoplexes observed through crossed polars, spectrophotometry of reduced and oxidized BFDMA in the presence and absence of DOPE, and SAXS spectra of BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

References

- 1.Patnaik S, Tripathi SK, Goyal R, Arora A, Mitra K, Villaverde A, Vazquez E, Shukla Y, Kumar P, Gupta KC. Soft Matter. 2011;7:6103–6112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziauddin J, Sabatini DM. Nature. 2001;411:107–110. doi: 10.1038/35075114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey SN, Wu RZ, Sabatini DM. Drug Discovery Today. 2002;7:S113–S118. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang FH, Lee CH, Chen MT, Kuo CC, Chiang YL, Hang CY, Roffler S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delehanty JB, Shaffer KM, Lin BC. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:7323–7328. doi: 10.1021/ac049259g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamauchi F, Kato K, Iwata H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamauchi F, Kato K, Iwata H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2004;1672:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengali Z, Pannier AK, Segura T, Anderson BC, Jang JH, Mustoe TA, Shea LD. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005;90:290–302. doi: 10.1002/bit.20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isalan M, Santori MI, Gonzalez C, Serrano L. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeth732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hook AL, Thissen H, Voelcker NH. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:573–579. doi: 10.1021/bm801217n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green DW, Mann S, Oreffo ROC. Soft Matter. 2006;2:732–737. doi: 10.1039/b604786f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saltzman WM, Olbricht WL. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2002;1:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltzman WM. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17:534–535. doi: 10.1038/9835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea LD, Smiley E, Bonadio J, Mooney DJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:551–554. doi: 10.1038/9853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson TP, Murphy WL, Mooney DJ. Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 2001;11:47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepard JA, Huang A, Shikanov A, Shea LD. J. Controlled Release. 2010;146:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang F, Cho SW, Son SM, Bogatyrev SR, Singh D, Green JJ, Mei Y, Park S, Bhang SH, Kim BS, Langer R, Anderson DG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:3317–3322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandal S, Rosso N, Tiribelli C, Scoles G, Krol S. Soft Matter. 2011;7:9424–9434. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillot-Nieckowski M, Eisler S, Diederich F. New Journal of Chemistry. 2007;31:1111–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, Basile CD, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, Selz F, Hue C, Certain S, Casanova JL, Bousso P, Le Deist F, Fischer A. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, Yates F, de Villartay JP, Le Deist F, Fischer A. J. Gene Med. 2001;3:201–206. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200105/06)3:3<201::AID-JGM195>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Thrasher A, Mavilio F. Nature. 2004;427:779–781. doi: 10.1038/427779a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard WJ. Mol. Med. Today. 2000;6:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01782-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Le Deist F, Carlier F, Bouneaud C, Hue C, De Villartay J, Thrasher AJ, Wulffraat N, Sorensen R, Dupuis-Girod S, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Davies EG, Kuis W, Lundlaan WHK, Leiva L. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:1185–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer A, Hacein-Bey S, Cavazzana-Calvo M. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:615–621. doi: 10.1038/nri859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaspar HB, Howe S, Thrasher AJ. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1999–2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman RJ. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999;10:2091–2107. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohn DB. J. Intern. Med. 2001;249:379–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimichele D, Miller FG, Fins JJ. Haemophilia. 2003;9:145–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain JS. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2355–2362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.20.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregorevic P, Chamberlain JS. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2003;3:803–814. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Deutekom JCT, van Ommen GJB. Nature Rev. Genet. 2003;4:774–783. doi: 10.1038/nrg1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishikawa M, Huang L. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001;12:861–870. doi: 10.1089/104303401750195836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niidome T, Huang L. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1647–1652. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Nature Biotechnol. 2000;18:33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felgner PL, Ringold GM. Nature. 1989;337:387–388. doi: 10.1038/337387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabanov AV FP, Seymour LW. Self-Assembling Complexes for Gene Delivery: From Laboratory to Clinical Trial. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo X, Szoka FC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:335–341. doi: 10.1021/ar9703241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang FX, Hughes JA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:141–145. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang FX, Hughes JA. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:791–796. doi: 10.1021/bc990016i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang FX, Wang W, Hughes JA. J. Liposome Res. 1999;9:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ajmani PS, Tang FX, Krishnaswami S, Meyer EM, Sumners C, Hughes JA. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;277:141–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00856-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balakirev M, Schoehn G, Chroboczek J. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:813–819. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byk G, Wetzer B, Frederic M, Dubertret C, Pitard B, Jaslin G, Scherman D. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:4377–4387. doi: 10.1021/jm000284y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wetzer B, Byk G, Frederic M, Airiau M, Blanche F, Pitard B, Scherman D. Biochem. J. 2001;356:747–756. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar VV, Chaudhuri A. FEBS Lett. 2004;571:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang ZH, Li WJ, MacKay JA, Szoka FC. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Budker V, Gurevich V, Hagstrom JE, Bortzov F, Wolff JA. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:760–764. doi: 10.1038/nbt0696-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerasimov OV, Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Thompson DH. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1999;38:317–338. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shum P, Kim JM, Thompson DH. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;53:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meers P. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;53:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prata CAH, Zhao YX, Barthelemy P, Li YG, Luo D, McIntosh TJ, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12196–12197. doi: 10.1021/ja0474906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang XX, Prata CAH, Berlin JA, McIntosh TJ, Barthelemy P, Grinstaff MW. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:690–699. doi: 10.1021/bc1004526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abbott NL, Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Lynn DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11576–11577. doi: 10.1021/ja054038t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. J. Controlled Release. 2006;112:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:2120–2128. doi: 10.1021/bc8002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pizzey CL, Jewell CM, Hays ME, Lynn DM, Abbott NL, Kondo Y, Golan S, Talmon Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:5849–5857. doi: 10.1021/jp7103903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hays ME, Jewell CM, Kondo Y, Lynn DM, Abbott NL. Biophys. J. 2007;93:4414–4424. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Golan S, Aytar BS, Muller JPE, Kondo Y, Lynn DM, Abbott NL, Talmon Y. Langmuir. 2011;27:6615–6621. doi: 10.1021/la200450x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aytar BS, Muller JPE, Golan S, Hata S, Takahashi H, Kondo Y, Talmon Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hays ME, Jewell CM, Lynn DM, Abbott NL. Langmuir. 2007;23:5609–5614. doi: 10.1021/la0700319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hui SW, Langner M, Zhao YL, Ross P, Hurley E, Chan K. Biophys. J. 1996;71:590–599. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79309-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caracciolo G, Callipo L, De Sanctis SC, Cavaliere C, Pozzi D, Lagana A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2010;1798:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Audouy S, Molema G, de Leij L, Hoekstra D. J. Gene. Med. 2000;2:465–476. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200011/12)2:6<465::AID-JGM141>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zelphati O, Uyechi LS, Barron LG, Szoka FC. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Lipids Lipid Metab. 1998;1390:119–133. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang JP, Huang L. Gene Ther. 1997;4:950–960. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchini C, Montani M, Amici A, Amenitsch H, Marianecci C, Pozzi D, Caracciolo G. Langmuir. 2009;25:3013–3021. doi: 10.1021/la8033726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ewert K, Slack NL, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Lin AJ, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:133–149. doi: 10.2174/0929867043456160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tate MW, Gruner SM. Biochemistry. 1987;26:231–236. doi: 10.1021/bi00375a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koltover I, Salditt T, Radler JO, Safinya CR. Science. 1998;281:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miller AD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:1769–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muñoz-Úbeda M, Rodríguez-Pulido A, Nogales A, Llorca O, Quesada-Pérez M, Martín-Molina A, Aicart E, Junquera E. Soft Matter. 2011;7:5991–6004. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verkleij AJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;779:43–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(84)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chernomordik LV, Zimmerberg J. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1995;5:541–547. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hui SW, Stewart TP, Boni LT, Yeagle PL. Science. 1981;212:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.7233185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rädler JO, Koltover I, Salditt T, Safinya CR. Science. 1997;275:810–814. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shier D, Butler J, Lewis R. Hole's Human Anatomy & Physiology. McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Templeton NS. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1279–1287. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kakizawa Y, Sakai H, Nishiyama K, Abe M, Shoji H, Kondo Y, Yoshino N. Langmuir. 1996;12:921–924. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kakizawa Y, Sakai H, Yamaguchi A, Kondo Y, Yoshino N, Abe M. Langmuir. 2001;17:8044–8048. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yoshino N, Shoji H, Kondo Y, Kakizawa Y, Sakai H, Abe M. J. Jpn. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996;45:769–775. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu XY, Abbott NL. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:15554–15564. doi: 10.1021/jp107936b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang TC, Toraya H, Blanton TN, Wu Y. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koynova R, Tenchov B, Wang L, MacDonald RC. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2009;6:951–958. doi: 10.1021/mp8002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seddon JM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1031:1–69. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(90)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bilalov A, Olsson U, Lindman B. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3827–3830. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Corsi J, Hawtin RW, Ces O, Attard GS, Khalid S. Langmuir. 2010;26:12119–12125. doi: 10.1021/la101448m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li S, Rizzo MA, Bhattacharya S, Huang L. Gene Ther. 1998;5:930–937. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li S, Tseng WC, Stolz DB, Wu SP, Watkins SC, Huang L. Gene Ther. 1999;6:585–594. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.