Abstract

Genes functioning in folate-mediated 1-carbon metabolism are hypothesized to play a role in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk beyond the current narrow focus on the MTHFR 677 C→T (rs1801133) polymorphism. Using a cohort study design, we investigated whether sequence variants in the network of folate-related genes, particularly in genes encoding proteins related to SHMT1, predict CVD risk in 1131 men from the Normative Aging Study. A total of 330 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 52 genes, selected for function and gene coverage, were assayed on the Illumina GoldenGate platform. Age- and smoking-adjusted genotype-phenotype associations were estimated in regression models. Using a nominal P ≤ 5.00 × 10−3 significance threshold, 8 SNPs were associated with CVD risk in single locus analyses. Using a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold (P-adjusted ≤1.00 × 10−1), a SNP in the GGH gene remained associated with reduced CVD risk, with a stronger association in early onset CVD cases (<55 y). A gene × folate interaction (MAT2B) and 2 gene × vitamin B-12 interactions (BHMT, SLC25A32) reached the FDR P-adjusted ≤2.00 × 10−1 threshold. Three biological hypotheses related to SHMT1 were explored and significant gene × gene interactions were identified for TYMS by UBE2N, FTH1 by CELF1, and TYMS by MTHFR. Variations in genes other than MTHFR and those directly involved in homocysteine metabolism are associated with CVD risk in non-Hispanic white males. This work supports a role for SHMT1-related genes and nuclear folate metabolism, including the thymidylate biosynthesis pathway, in mediating CVD risk.

Introduction

Heart disease and stroke were responsible for about one-third of U.S. deaths in 2004 (1). There is extensive evidence for the contribution of dietary and lifestyle factors to risk; however, the origins of cardiovascular disease (CVD)13 are complex and the interactive effects of genetic and environmental factors, including nutrition, play an important role.

Folate and other B vitamins contribute to biological processes important to health, including DNA synthesis and repair, and the generation of cellular methylation potential for a variety of methylation reactions. Folate status is influenced by dietary intake and variation in the genes encoding folate-related enzymes; altered folate status is associated with adverse outcomes, including birth defects, CVD, and cancer (2). Elevated plasma homocysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, is a marker of disturbed folate-mediated 1-carbon metabolism, and is associated with an increased risk of CVD (3–6). Homocysteine concentrations are modulated by nutrition, particularly folate and vitamin B-12 (7), and by genetic variants, including a well-studied single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene (MTHFR 677 C→T; rs1801133) (8). Thus, the association of sequence variation in the 1-carbon network with CVD may be mediated through altered homocysteine metabolism, cellular methylation potential, and/or DNA synthesis.

Although several candidate genes contributing to folate-mediated, 1-carbon metabolism have been extensively studied in relation to CVD risk, most notably the MTHFR rs1801133 SNP, other genes less proximal to homocysteine metabolism are understudied. A recent publication examined the association of genetic variation in the 1-carbon network and related nutritional factors with biological markers of CVD risk [plasma homocysteine and global genomic DNA methylation (9)], and a similar evaluation of CVD is needed. A more complete understanding of the role of the 1-carbon network in mediating CVD risk would support the development of novel prevention strategies. This study investigated 330 SNPs in 52 genes that play a role in folate-mediated, 1-carbon metabolism. The set of genes, SNPs, and biomarkers examined in this study was purposefully selected to represent the full functional variation of the folate-mediated, 1-carbon metabolic network and prospectively evaluated for association with CVD in a U.S. population studied prior to the initiation of mandatory folate fortification.

Participants and Methods

Study population.

The longitudinal Normative Aging Study (NAS) was established by the Veterans Administration in 1961 and men were followed-up at 3- to 5-y intervals through 1998 (end date for this study); 2280 men aged 21–81 y (mean age 42 y at study entry) were enrolled based on health criteria (10).

DNA extraction, SNP selection, and genotyping.

DNA extraction, SNP selection, and genotyping were carried out as described elsewhere (9). Fifty-two genes contributing to folate-mediated, 1-carbon metabolism were identified (Supplemental Table 1). SNP selection encompassed 2 kb on either side of the gene to include promoter and/or regulatory region variants. SNPs within a gene were selected to minimize redundancy (9). No assumptions were made about a given SNP representing gain or loss of function and SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥5% in European-ancestry populations were selected where possible, although exceptions were made for SNPs with prior evidence of putative function or when no SNPs with a MAF ≥5% were available [details presented elsewhere (9)]. A total of 384 SNPs were submitted to the Center for Inherited Disease Research at Johns Hopkins University for genotyping via an Illumina GoldenGate custom panel; 54 SNPs were ultimately excluded (reasons included assay failure, monomorphic genotype data, MAF <1%, and genotype frequencies out of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium), leaving 330 SNPs for analysis (Supplemental Table 2). SNP selection was completed in January 2008. A total of 1304 participant samples were submitted for genotyping: 54.4% were genomic and 45.5% were whole-genome amplified. This study included the 1131 successfully genotyped, non-Hispanic, white males.

Covariates.

Extensive previously collected data on NAS participants included physical measurements, lifestyle factors, and blood biomarkers; the methods for covariate measurement were previously described (11–14). Since enrollment, participants have had clinical examinations at 3- to 5-y intervals, with a response rate of >90% for mailed questionnaires. Plasma biomarkers were assayed in an unselected subset of stored blood samples; CV were excellent [folate, 4.3%; vitamin B-6 (pyridoxal-5′-phosphate), 5.0%; vitamin B-12, 4.7%; total homocysteine, 4.0%] (11).

Up to 3 measurements of homocysteine, folate, vitamin B-6, and vitamin B-12 were available prior to December 31, 1998, the end of follow-up, which coincided approximately with the start of mandatory folate fortification in the US. The intraclass correlation coefficients for log-transformed homocysteine, folate, vitamin B-6, and vitamin B-12 confirmed that a high proportion of the total variance was between- (vs. within-) person; thus, the first available biomarker measurement was used to best represent nutrient status in the pre-fortification era and to maximize case number, because only cases with nutrients measured prior to disease onset were included. The biomarkers were frequently measured together and the date range corresponding to the first available measure of each biomarker was April 1993 to December 1998. All biomarkers were log-transformed to adjust for skewness and centered for best performance in regression models.

Phenotype assessment.

In this longitudinal cohort study, follow-up time for study participants was estimated as time from study baseline to first occurrence of a CVD event (angina; fatal and nonfatal MI or other coronary heart disease; fatal and nonfatal stroke) or death from a competing cause. For all other men, follow-up time was time from baseline to December 31, 1998, the end of follow-up for all study analyses.

The ascertainment of CVD events within the NAS is described elsewhere (13, 15). Briefly, the possible occurrence of nonfatal MI and angina was ascertained by participant report and confirmed by a cardiologist. Similarly, the occurrence of a nonfatal stroke was ascertained by participant report and confirmed by a neurologist. Fatal myocardial infarction and fatal stroke in men with no prior history of CVD were ascertained through death certificates, which were reviewed by a cardiologist who assigned cause of death using International Classification of Disease codes. CVD events comprised the following diagnosis codes (International Classification of Disease, version 8): 410–414.9 (heart disease including angina and myocardial infarction), and 436.9, 430, 431 (stroke). Ascertainment of fatal CVD events was nearly 100% (13, 16). In all instances, the confirming physician was unaware of the participant’s exposure status (genotype). From 1964 to 1998, 381 cases of fatal or nonfatal CVD occurred among the 1131 men with successful Illumina genotyping (31,871 person-years of follow-up).

Statistical analyses.

Time-to-event analysis evaluated the relation of SNP markers to CVD risk by using a Cox proportional hazards model. Genetic models of inheritance (additive, dominant, recessive, and overdominant) were tested for each SNP and the model most significantly associated with CVD risk in the unadjusted single SNP analysis was chosen as the best model going forward. SNP main effects were captured in a single term; significance of the SNP was assessed by the P value for the SNP regression coefficient. Although the first selection step affects the P value distribution going forward, no additional multiple testing corrections were applied beyond the false discovery rate (FDR) given that the P values from the various models were not independent (e.g., between additive and dominant models) and because the work was hypothesis oriented and seeking to nominate candidate genes for further investigation. For the MTHFR rs1801133 SNP, a dummy-coded scheme was used for consistency to past work, which almost universally evaluates the CT and TT genotypes separately against the CC reference category (6, 15, 17), and the likelihood ratio test (LRT) P value was used to assess significance of the set of dummy variables. The potentially confounding factors considered included age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, alcohol consumption, and education; however, only age, smoking, diabetes, and hypertension were associated with CVD and thus these variables were considered in further models. All regression models were adjusted for age and smoking status (baseline smoking status and change in smoking status over follow-up) and sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the SNP-CVD association adjusted for diabetes and hypertension comorbidities. Extended models adjusted for biomarker residuals (i.e., variation in nutrient biomarker not predicted by SNP) and the MTHFR rs1801133 variant (using recessive coding to account for the pattern of association using the fewest model terms). Previous work in this cohort demonstrated no population substructure (18); thus, no adjustments were made.

To investigate whether nutrient status modified the genotype-phenotype association, gene × nutrient interactions were evaluated. Product terms representing the interaction of each genotype with nutrient residuals (continuous variable) were included in models; significance was assessed by the P value for the interaction term. Where specific genetic models of inheritance led to sparse data for gene × nutrient interaction models, additive coding was used as the default. For the purposes of illustration, SNP-nutrient interactions are presented at 3 values of the centered, log-transformed nutrients: the 10th percentile (low), the 50th percentile (median), and the 90th percentile (high). To assess the joint role of multiple genetic variants, gene × gene interactions were tested using model-free dummy variable coding; significance was assessed using the LRT P value for models with vs. models without interaction terms; sparse data prevented the evaluation of some interactions. Interactions affected by sparse data [<5 individuals in ≥1 cell of the SNP by SNP frequency table or improbably large regression estimates (likely indicates sparse data)] are presented in the online supplement only.

To account for multiple comparisons, the FDR multiple testing correction of Benjamini and Hochberg (19) was implemented (SAS, PROC MULTTEST with the FDR option) and can be considered a conditional FDR given the prior step identifying the best genetic model. For SNP main effects, regression coefficients with a nominal P ≤ 5.00 × 10−3 were reported and a conditional FDR-adjusted significance threshold of P-adjusted ≤0.1 was used, indicating that we expected <10% of tests flagged by this criterion to be false positives, conditioned on the genetic model selection step. In assessing interactions, a less stringent significance threshold was used: regression coefficients with a nominal P ≤2.00 × 10−2 were reported. However, for the network-wide gene × gene interaction analysis, a nominal P ≤1.00 × 10−3 threshold was used to limit the number of results reported.

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS v. 9.2 unless otherwise specified. The study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Human Subjects committee, the Veterans Administration Research and Development Committee, and the Cornell University Committee on Human Subjects.

Results

Among 1131 men with genotype data, 381 CVD cases occurred: 14% myocardial infarction only, 17% angina only, 4% other coronary heart disease only, and 8% stroke only. The remainder had multiple diagnoses. A subset of 735 men had measurements for plasma nutrient biomarkers (folate, vitamins B-6 and B-12, and homocysteine). Among the study participants, the MTHFR rs1801133 TT genotype frequency was 12.8%, representing >2200 chromosomes (Table 1); this frequency is higher than a sample of 120 chromosomes from the HapMap CEPH population (6.7% TT) but similar to a sample of 5064 chromosomes from North American coronary heart disease controls in a meta-analysis (12.2% TT) (8). In exploratory regression models, prior to assessing the genotype-phenotype associations, baseline age was associated with CVD risk (P ≤1.00 × 10−4), as were baseline smoking status and change in smoking status over follow-up (P ≤ 2.00 × 10−3 for each term). When modeled individually, plasma folate (P = 9.00 × 10−1) and vitamin B-12 (P = 7.00 × 10−1) had little or no association with CVD, although vitamin B-6 (P = 7.70 × 10−2) and homocysteine (P = 5.40 × 10−2) had some association in unadjusted models; the associations were attenuated in age- and smoking- adjusted models.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of NAS participants at study baseline1

| Variable | n | |

| Age, y | 40.2 ± 7.8 | 1131 |

| Education, % college graduate or higher | 28.1 | 1086 |

| White, % | 100 | 1131 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 2.9 | 1113 |

| Obese, % BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 8.5 | 1113 |

| Cigarette smoking, % | 1117 | |

| Current | 30.1 | |

| Former | 37.5 | |

| Never | 32.4 | |

| Alcohol intake, % ≥2 drinks/d | 13.4 | 1131 |

| Serum fasting glucose, mmol/L | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 1121 |

| Diabetes diagnosis, % | 0.18 | 1121 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 123 ± 12.7 | 1127 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 76.6 ± 8.6 | 1127 |

| Hypertension diagnosis, % | 2.5 | 1131 |

| Serum total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 1129 |

| MTHFR 677 C→T (rs1801133) TT genotype, % | 12.8 | 1129 |

| Plasma folate,2 nmol/L | 23.6 ± 12.9 | 745 |

| Plasma vitamin B-6, nmol/L | 84.8 ± 85.0 | 760 |

| Plasma vitamin B-12, pmol/L | 338 ± 140 | 752 |

| Plasma homocysteine, μmol/L | 10.6 ± 3.7 | 760 |

| Mean follow-up time, y | 28.2 ± 6.7 | 1131 |

Values are percent or mean ± SD. NAS, Normative Aging Study.

Plasma measures of folate, vitamin B-6, vitamin B-12, and homocysteine were collected prior to the initiation of folate fortification.

Single locus marker associations.

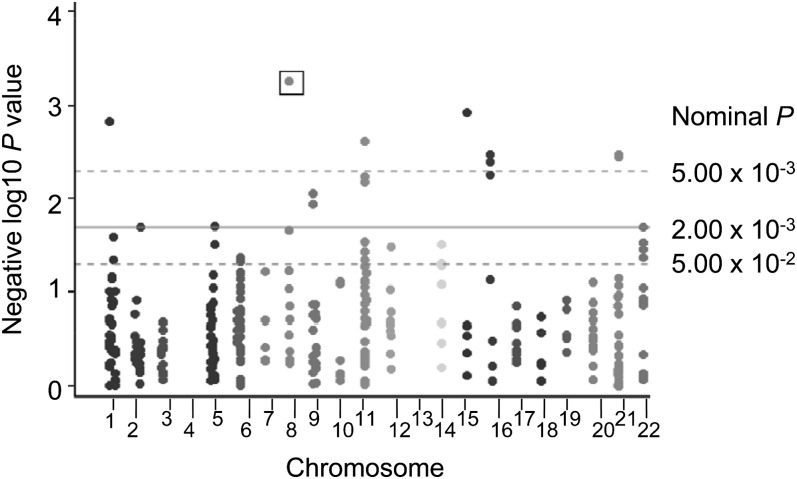

The 8 SNPs with nominal P ≤ 5.00 × 10−3 for the CVD phenotype (Fig. 1) were generally common variants with a MAF ≥13% (Table 2). γ-Glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) rs12544045, a 5′ region marker, had a nominal P = 5.50 × 10−4, P-adjusted = 9.10 × 10−2. Compared with the AA/GG genotype group, the AG genotype was associated with a 32% reduction in CVD risk [OR = 0.68 (95% CI: 0.5, 0.8)]. A SNP in 5, 10-methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase (MTHFS), rs7177659, was associated with reduced CVD risk; men in the AC genotype group had a 29% lower risk compared with the AA/CC genotype group [OR = 0.71 (95% CI: 0.6, 0.9)]. The well-known MTHFR rs1801133 SNP was associated with risk: CT (vs. CC) was associated with a 6% increase in CVD risk [OR = 1.06 (95% CI: 0.8, 1.3)], and TT (vs. CC) was associated with a 71% increase in CVD risk [OR = 1.71 (95% CI: 1.3, 2.3)]. Further adjusting for diabetes or hypertension (baseline status and change over follow-up) made little difference overall and identified the same set of SNPs, although regression coefficients and P values showed minor changes. When analyses were restricted to the subset of men with biomarker data (n = 735), the set of most significant SNPs, and the coefficient estimates and SE, were nearly identical in age- and smoking-adjusted models. Further adjusting models for the MTHFR rs1801133 variant made little or no difference to the set of most significant findings.

FIGURE 1.

Manhattan plot: folate-related SNPs as predictors of CVD risk in men from the NAS. Models adjusted for age and smoking status. The box indicates SNP that reached the FDR significance threshold. Eight SNPs are shown above the P = 5.00 × 10−3 dotted line, including 2 SNPs on chromosomes 16 and 21. No SNPs were located on chromosomes 4 or 13 or the sex chromosomes. CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDR, false discovery rate; NAS, Normative Aging Study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

TABLE 2.

SNPs associated with CVD risk in men from the NAS at nominal P ≤ 5.00 × 10−3,1ndash3

| Gene | rs number | β | SE | OR (95% CI) | Nominal P4 | Chr | Coded allele | Coded allele frequency % | Genetic model (number)5 | SNP type |

| GGH | rs12544045 | −0.38 | 0.11 | 0.68 (0.6, 0.9) | 5.51 x 10−4* | 8 | A | 29 | O (AG : 464, AA + GG : 660) | 5′ |

| MTHFS | rs7177659 | −0.34 | 0.11 | 0.71 (0.6, 0.9) | 1.18 x 10−3 | 15 | A | 47 | O (AC : 572, AA + CC : 558) | I |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 CT | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1.06 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.48 x 10−3 | 1 | T | 35 | (CC : 482, CT : 502, TT : 145) | N |

| rs1801133 TT | 0.54 | 0.15 | 1.71 (1.3, 2.3) | |||||||

| TCN1 | rs17154234 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 1.62 (1.2, 2.2) | 2.40 x 10−3 | 11 | C | 5 | O (CT : 103, CC + TT : 1027) | 3′ |

| UBE2I | rs11248868 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 1.40 (1.1, 1.8) | 3.33 x 10−3 | 16 | G | 13 | O (GT : 270, GG + TT : 858) | I |

| CBS | rs6586282 | −0.32 | 0.11 | 0.73 (0.6, 0.9) | 3.35 x 10−3 | 21 | T | 18 | A (CC : 759, CT : 335, TT : 31) | I |

| CBS | rs6586281 | −0.35 | 0.12 | 0.71 (0.6, 0.9) | 3.55 x 10−3 | 21 | A | 18 | DOM (AA + G : 365, GG : 756) | I |

| UBE2I | rs909915 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 1.39 (1.1, 1.7) | 4.02 x 10−3 | 16 | T | 13 | O (TC : 268, TT + CC : 860) | I |

Model adjusted for age and smoking; forward strand allele shown. A, additive; N, coding nonsynonomous; Chr, chromosome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DOM, dominant; FDR, false discovery rate; I, intron; LRT, likelihood ratio test; NAS, Normative Aging Study; O, overdominant; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

No SNPs map to more than one gene.

No lower quality SNPs.

The significance threshold for inclusion in table was ≤ 5.00 × 10−3. P value represents P value for SNP main effect regression coefficient; for the MTHFR rs1801133 SNP the LRT P value is shown (λ2 = 13.033, 2 df). *Adjusted P value reached FDR significance threshold of P-adjusted ≤ 1.00 × 10−1.

Numbers shown are numbers of men in the indicated genotype groups.

Of the 8 SNPs with nominal P ≤ 5.00 × 10−3, 2 SNP-CVD associations (rs6586282 and rs6586281, both in the cystathionine-beta-synthase gene, CBS) were substantially mediated by nutritional status. Regression coefficients were reduced by ~36% when adjusted for plasma folate; further adjustment for vitamins B-6 and B-12 and homocysteine had no effect (Supplemental Table 3). For some SNPs, associations were strengthened after adding nutrient terms to the model. After adjusting for plasma folate, vitamin B-6, vitamin B-12, and homocysteine, the MTHFS rs7177659-CVD association increased 60%, the TCN1 rs17154234-CVD association increased 18%, the MTHFR rs1801133 CT-CVD association increased 163%, and the MTHFR rs1801133 TT-CVD association increased 21%.

Sensitivity analyses considered only those men with complete follow-up data (i.e., never missed a scheduled NAS follow-up visit by >1 y), and regression coefficients and SE were similar to models including all participants. When the outcome was limited to early-onset CVD (onset age <55 y), associations for some of the SNPs were strengthened, whereas other associations were attenuated (Supplemental Table 4). The GGH rs12544045 SNP association with CVD increased by 215% in the analysis limited to early-onset cases (nominal P = 2.90 × 10−4, P-adjusted = 9.50 × 10−2). Compared with the AA/GG genotype group, the AG genotype was associated with a 70% reduction in CVD risk for early onset cases [OR = 0.3 (95% CI: 0.2, 0.6)]. MTHFR rs1801133 associations were consistent in direction of effect for early onset (P = 3.40 × 10−1) and all CVD (P = 1.50 × 10−3). Effect sizes for markers in the UBE2I gene, which encodes a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-conjugating enzyme (rs11248868, rs909915, and rs9926094), were approximately doubled in the early onset CVD analysis.

Gene-nutrient interactions.

Plasma folate and vitamins B-6 and B-12 are cofactors for enzymes in the 1-carbon metabolic network and may modify the SNP-phenotype association. In further analyses assessing SNP by nutrient interactions, one folate interaction term, with the rs6882306 variant in the methionine adenosyltransferase II, beta (MAT2B) gene, reached FDR significance levels (P-adjusted ≤2.00 × 10−1) (Supplemental Table 5). Compared with the CT/TT genotype group, men with the CC genotype had 91% lower, 42% lower, and 7-fold greater CVD risk at high (39.1 nmol/L), median (21.8 nmol/L), and low (9.9 nmol/L) plasma folate concentrations, respectively. Two vitamin B-12 interaction terms were significant at FDR thresholds: for the rs585800 SNP in betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT), compared with the AA/TT genotype group, men with the TA genotype had 36% lower, 19% higher, and 2.2-fold higher CVD risk at high (501 pmol/L), median (309 pmol/L), and low (191 pmol/L) plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations, respectively. For the rs1061196 SNP in solute carrier family 25, member 32 (SLC25A32), compared with the AA/GG genotype group, men with the AG genotype had 1.6-fold higher, 17% lower, and 55% lower CVD risk at high, median, and low plasma B-12 concentrations, respectively. No vitamin B-6 interaction terms reached the FDR significance level of P-adjusted ≤2.00 × 10−1.

Gene-gene interactions.

In models investigating interactions between MTHFR rs1801133 and each SNP marker, 6 interactions reached the nominal level of P ≤ 2.00 × 10−2; no interactions were significant at the a priori FDR significance threshold of P-adjusted ≤ 2.00 × 10−1 (Supplemental Table 6).

Given the interconnectedness of folate-mediated, 1-carbon metabolism, gene-gene interactions within the network were hypothesized to predict CVD risk. Thus, an analysis of all pairwise gene-gene interactions within the network was conducted. Of 52,832 unique pairwise interactions tested, 55 were associated with CVD risk at P ≤ 1.00 × 10−3; no interactions were significant at an FDR P-adjusted ≤ 2.00 × 10−1 (Supplemental Table 7). The interaction between CELF1 (formerly CUGBP1) rs7933019 and MTR rs16834388 reached nominal P = 1.20 × 10−4. In men with the CELF1 rs7933019 GG genotype, MTR rs16834388 GT and TT genotypes were associated with an increased risk of CVD (by 30 and 73%, respectively, vs. MTR rs16834388 GG genotype), whereas in men with the CELF1 rs7933019 CC genotype, the MTR GT and TT genotypes were inversely associated with CVD risk (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Association of CELF1 rs7933019 and MTR rs16834388 with CVD risk in men from the NAS1ndash3

| Gene | Genotype | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | LRT P4 |

| CELF1 rs7933019 : | GG | CG | CC | 1.20 x 10−4, 5 | ||||

| MTR rs16834388 | GT vs. GG | 1.30 (0.9, 1.8) | 258 | 1.03 (0.7, 1.4) | 220 | 0.39 (0.2, 0.8) | 52 | |

| TT vs. GG | 1.73 (1.1, 2.7) | 80 | 1.00 (0.6, 1.7) | 60 | 0.13 (0.0, 0.4) | 22 | ||

Model adjusted for age and smoking; forward strand allele shown. CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDR, false discovery rate; LRT, likelihood ratio test; NAS, Normative Aging Study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

No SNPs map to more than one gene.

No lower quality SNPs.

value represents LRT for models with vs. without interaction terms.

Interaction did not reach FDR significance threshold of adjusted ≤2.00 × 10−1.

Several hypotheses arising from animal and cell studies and prior population-level studies were investigated. Prior studies (15, 20) reported a gene × gene interaction for MTHFR by SHMT1; the interaction was replicated here and mediation by folate, vitamins B-6 and B-12, and homocysteine was explored. Adjusting for homocysteine strengthened the interaction (LRT P = 1.00 × 10−2). Thus, in men with the SHMT1 rs1979277 TT genotype, the MTHFR rs1801133 CT genotype was associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk of CVD (vs. the rs1801133 CC genotype) and the MTHFR rs1801133 CT genotype was associated with a 10.4-fold increased risk of CVD (vs. the rs1801133 CC genotype) in models adjusted for homocysteine. Similarly, in men with the SHMT1 rs1979277 TT genotype, the MTHFR rs1801133 TT genotype (vs. rs1801133 CC genotype) was associated with a 3-fold increased risk of CVD without adjusting for homocysteine and a 15-fold increased risk of CVD with adjustment for homocysteine. There was little or no association of the MTHFR genotype with CVD risk in the subgroup of men with the SHMT1 rs1979277 CT/CC genotype either with or without adjusting for homocysteine.

The SHMT1 enzyme governs the competing flow of 1-carbon units to thymidylate biosynthesis or remethylation reactions (21); thus, modifications in protein expression or subcellular location may affect CVD risk by influencing the distribution of 1-carbon units to competing reactions. Three hypotheses related to SHMT1 were investigated. First, a nuclear 1-carbon metabolism hypothesis was evaluated by considering all pairwise interactions among SNPs in the SHMT1, TYMS, DHFR, UBE2I, and UBE2N genes in relation to CVD risk. Of 451 unique pairwise interactions tested, 8 reached nominal (P ≤ 2.00 × 10−2) (Supplemental Table 8). The most significant finding was the interaction of UBE2N rs7300607 and TYMS rs502396 (Table 4); among men with the TYMS rs502396 CC genotype, the UBE2N rs7300607 CC genotype increased CVD risk 3-fold (vs. rs7300607 TT reference group). Second, an SHMT1 expression hypothesis (22) was explored and all pairwise interactions among SNPs in the FTH1, CELF1, and SHMT1 genes were investigated in relation to CVD risk. Of 92 unique pairwise interactions tested, 12 reached nominal (P ≤ 2.00 × 10−2) (Supplemental Table 9). The interaction of FTH1 rs17156609 and CELF1 rs7933019 (Table 4) was significant; among men with the FTH1 rs17156609 GA genotype, the CELF1 rs7933019 CC genotype increased CVD risk 3-fold (vs. rs7933019 GG reference group). One category, FTH1 rs17156609 AA / CELF1 rs7933019 CC, could not be evaluated due to sparse data. Finally, because mitochondrial folate metabolism produces formate, a major source of cytoplasmic 1-carbon units (2), interactions may exist among MTHFD1L, SHMT1 [influences 1-carbon unit distribution among the remethylation and thymidylate synthesis pathways (21)], and 2 downstream enzymes in each pathway, MTHFR and TYMS (the mitochondrial 1-carbon metabolism hypothesis). Of 377 unique pairwise interactions tested, 2 reached the nominal P ≤ 2.00 × 10−2 threshold (Supplemental Table 10). The interaction of TYMS rs502396 and MTHFR rs12121543 (Table 4) exemplifies the finding that in men with the TYMS rs502396 CC genotype, the MTHFR rs12121543 AA genotype increased CVD risk 2-fold (vs. rs12121543 CC reference group).

TABLE 4.

| Hypothesis | Gene | Genotype | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | LRT P3 |

| Nuclear 1-carbon metabolism | TYMS rs502396 : | TT | TC | CC | 3.40 x 10−3 | ||||

| UBE2N rs7300607 | TC vs. TT | 0.77 (0.5, 1.2) | 165 | 1.20 (0.8, 1.7) | 292 | 3.60 (1.7, 7.6) | 136 | ||

| CC vs. TT | 1.29 (0.8, 2.1) | 74 | 1.21 (0.8, 1.9) | 109 | 3.13 (1.4, 7.0) | 63 | |||

| SHMT1 expression | FTH1 rs17156609 :4 | GG | GA | AA | 7.40 x 10−3 | ||||

| CELF1 rs7933019 | CG vs. GG | 1.08 (0.9, 1.3) | 459 | 0.35 (0.1, 1.5) | 19 | 05 | |||

| CC vs. GG | 0.92 (0.6, 1.4) | 100 | 3.27 (1.2, 8.7) | 10 | 05 | ||||

| Mitochondrial 1-carbon metabolism | TYMS rs502396 : | TT | CT | CC | 1.00 x 10−2 | ||||

| MTHFR rs12121543 | AC vs. CC | 0.93 (0.6, 1.4) | 115 | 1.22 (0.9, 1.7) | 182 | 0.88 (0.5, 1.4) | 97 | ||

| AA vs. CC | 0.21 (0.1, 0.7) | 25 | 0.67 (0.3, 1.4) | 30 | 1.83 (0.9, 3.9) | 15 |

Model adjusted for age and smoking; forward strand allele shown. CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDR, false discovery rate; LRT, likelihood ratio test; NAS, Normative Aging Study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

No lower quality SNPs.

value represents LRT for models with vs. without interaction terms. Presented P values were not FDR-adjusted in this hypothesis-driven analysis.

SNP maps to more than one gene: rs17156609 also maps to bestrophin 1 (BEST1).

The rs17156609 AA genotype did not exist in this dataset and therefore the associated OR are not estimated.

A landmark GWAS, the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, previously identified an intronic SNP (rs6922269) in MTHFD1L, a mitochondrial folate metabolism gene, which was associated with coronary artery disease risk (23). Based on HapMap linkage plots, this SNP is located in a tightly linked 14-kb block in the MTHFD1L gene. Although the intronic rs6922269 SNP, along with the nearby nonsynonymous rs9767752 SNP, were not assayed (both failed in the genotyping), 6 other tag SNPs successfully cover this region. Joint genotypes involving 2 SNPs within the 14-kb region (rs1474787 and rs803447) best captured the association with CVD risk. In the rs1474787 GA genotype group, men with the rs803447 TT genotype had a 3.6-fold increased CVD risk compared with the rs803447 CC reference group (P-interaction = 0.077). One category, the rs1474787 AA / rs803447 TT genotype group, could not be evaluated due to sparse data. In models adjusted for homocysteine, the interaction was strengthened; thus, in the rs1474787 GA genotype group, men with the rs803447 TT genotype had a 6-fold increased risk of CVD compared with the rs803447 CC reference group (P-interaction = 0.077) (data not shown).

Discussion

We investigated sequence variation in a network of candidate genes involved in 1-carbon metabolism in relation to CVD risk and several specific hypotheses based on animal and cell studies were confirmed in this population-level study. Overall, there was little evidence that plasma nutrients or homocysteine mediated the SNP-CVD risk associations. Among the genes considered, an FDR-significant association was identified for a GGH 5′ region SNP; the rs12544045 AG genotype was associated with a 32% reduction in CVD risk. The GGH enzyme facilitates cellular folate export and previous work identified polymorphisms in the GGH 5′ region that were associated with increased promoter activity (24) and DNA uracil content (25). After plasma folate adjustment, the GGH-CVD association decreased only slightly, suggesting that plasma folate does not fully mediate the association of GGH rs12544045 with CVD or that our understanding of the role of GGH in contributing to CVD risk is incomplete. When restricted to early onset cases (onset age <55 y), main effects for GGH rs12544045 were stronger, consistent with a true effect on risk. In the MTHFS gene, the rs7177659 AC genotype was associated with a 29% reduction in CVD risk, although the functional significance of the variant allele is not known. MTHFS is an essential enzyme in mice that regulates de novo purine biosynthesis and catalyzes the conversion of 5-formyltetrahydrofolate to methenyltetrahydrofolate (26). Increased expression of MTHFS enhances purine biosynthesis (27, 28), potentially by delivering the substrate 10-formyltetrahydrofolate to the purinosome, a multienzyme complex (29).

Focusing on the SHMT1 intersection in the folate network, several specific hypotheses based on animal and cell studies were confirmed in this population-level study. In vitro studies demonstrated protein interactions between SHMT1 and UBC9 (yeast homolog of human UBE2I), resulting in the SUMOylation and nuclear localization of SHMT1, along with the other 2 components of thymidylate synthesis, TYMS and DHFR (30–32). UBC13 (yeast homolog of human UBE2N) is also a SHMT1 binding partner, suggesting that SHMT1 may be a target for ubiquitination (30). We could not directly assess SHMT1 by UBE2I interactions due to sparse data. However, the UBE2N by TYMS interaction was nominally significant; the protein products of these 2 genes physically interact during the sumoylation of TYMS. Other studies suggest that CELF1 (formerly CUGBP1) and FTH1 interact with the 3′-untranslated region and 5′-untranslated region of SHMT1 mRNA to upregulate translation (22). CELF1 and FTH1 were shown to physically interact, consistent with our findings demonstrating significant interactions for the gene pair FTH1-CELF1. Dysregulation of SHMT1 expression may be fundamental to folate-associated pathologies; a 50% reduction in expression sensitizes mice to intestinal carcinogenesis (33) and neural tube defects (34).

Gene-nutrient interactions.

The association of genetic variants with CVD risk may be modified by nutrient status. The previously identified MTHFR rs1801133-folate interaction (8, 35) was not significant in these data (P = 9.00 × 10−1); the relatively high folate status in this cohort, compared with NHANES data (36), may explain the lack of interaction. In analyses restricted to men with folate concentrations below the 25th percentile (<14.0 nmol/L; 187 men, 59 CVD events), the interaction was evident, marginally significant, and effect sizes were consistent with previous studies (5, 6, 8, 37, 38).

Considering vitamin B-6, no interactions between studied SNPs and vitamin B-6 reached the FDR threshold for significance. However, FDR-significant interactions were identified for plasma folate (MAT2B rs6882306) and vitamin B-12 (BHMT rs585800 and SLC25A32 rs1061196). The few gene-nutrient interactions identified may reflect limited power or the lack of men with low B vitamin status, even within this pre–folate fortification cohort.

The MAT2B gene product regulates S-adenosylmethionine synthesis. rs6882306 is an intronic SNP, but HapMap plots, although incomplete, suggest high linkage across the gene. Although MAT2B polymorphisms are not known to interact with folate, a recent study identified variants in a closely related gene, methionine adenosyltransferase I, alpha (MAT1A), that decreased risk of hypertension and DNA damage and increased risk of stroke independently of the MTHFR rs1801133 polymorphism (39). MAT1A interactions with folate predicted homocysteine and were consistent with the direction of effect reported here for the MAT2B-folate interaction and CVD risk.

The BHMT gene encodes a cytosolic enzyme that remethylates betaine to homocysteine. The rs585800 SNP is a 3′ region polymorphism and thus may have a regulatory function. Although BHMT is not known to bind vitamin B-12, previous work has identified regions homologous to bacterial vitamin B-12–dependent methionine synthases (40). In rats, hepatic BHMT activity was not sensitive to vitamin B-12 deficiency (41); however, epidemiologic work in humans suggests that enhancing methionine-synthase–dependent remethylation downregulates BHMT reactions (42), suggesting a mechanism for B-12 sensitivity.

The SLC25A32 gene encodes a folate transporter that shuttles folate into the mitochondria. The rs1061196 polymorphism is a 3′ region variant and thus may have a regulatory function. No prior reports link SLC25A32 to biochemical or disease phenotypes and a biological basis for the interaction of this gene with vitamin B-12 metabolism could not be identified.

The MTHFR rs1801133 TT-CVD association identified here [OR = 1.71 (95% CI: 1.3, 2.3)] is somewhat larger than previously reported despite the relatively folate-replete status of this population. Prior reports identified variability in the effect of the TT genotype (8), which may be due in part to differences in folate status between populations, but gene-gene interactions involving MTHFR rs1801133 (15, 20) may also play a role (Supplemental Table 6). Thus, interpretation of a MTHFR “main effect” association with CVD is complex, because differences in the interacting genotype frequency are expected to affect the risk estimates for the MTHFR genotype. Furthermore, the association of the MTHFR rs1801133 genotype with CVD risk was not entirely mediated through homocysteine, because the risks associated with MTHFR rs1801133 considered alone and in an interaction with SHMT1 rs1979277 both increased after adjusting for plasma nutrients and/or homocysteine.

Gene-gene interactions.

Considering the studied SNPs and MTHFR rs1801133, no interactions were significant at the FDR threshold. Similarly, of all network pairwise interactions evaluated, none exceeded the FDR significance threshold (P-adjusted ≤ 2.00 × 10−1).

Pleiotropic effects were examined across outcomes. Previously, SNPs associated with plasma homocysteine and global genomic DNA methylation were identified (9). Of 8 nominally significant SNPs identified in the CVD analysis, one pleiotropic SNP, CBS rs6586282, was strongly associated with the homocysteine phenotype (nominal P-CVD = 3.30 × 10−3, nominal P-homocysteine = 4.06 × 10−3); this SNP was also identified in a GWAS of the homocysteine phenotype (43). The CBS rs6586282 CT (vs. combined CC/TT) genotype was associated with a 5.8% reduction in plasma homocysteine; under an additive model, the T allele was associated with a 29% reduction in CVD risk. The CBS rs6586282 SNP was the only polymorphism in the CVD analysis mediated by nutrition, consistent with the association of this SNP with both homocysteine and CVD. Similarly, GGH was nominally significant for homocysteine and FDR significant for CVD; MTHFR was nominally significant for CVD and LINE-1 methylation.

The strengths of this study include a pathway-wide investigation of folate network genetic variation, use of a large cohort with CVD outcomes collected prior to the introduction of mandatory folate fortification, and a systematic approach to data analysis. The findings were corrected for multiple comparisons and hypotheses derived from animal and cell studies were explored. Despite restricting data to the pre–folate fortification period, the folate status of the population was relatively high, which may have attenuated some associations, and the study represents data from men only. Therefore, associations may differ in females.

In conclusion, variation in genes other than MTHFR and those directly involved in homocysteine metabolism are associated with CVD risk in 1131 non-Hispanic white males from the NAS. The epidemiologic findings presented herein replicated molecular biology studies of interactions among SHMT1-related proteins, supporting the importance of the SHMT1 intersection in folate metabolism in relation to CVD risk. These findings may help explain the limited success of randomized controlled trials focused on CVD risk reduction through homocysteine lowering (44, 45). A thorough understanding of the role of folate network genetic and nutritional variation in relation to CVD is important, particularly in the context of the numerous unfortified populations around the world.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

P.A.C. and S.M.W. designed the research; S.M.W., P.A.C., A.G.C., A.A.L., S.T.W., J.M.G., P.S.V., and K.L.T. conducted the research; S.M.W. and P.A.C. analyzed the data; S.M.W., P.A.C., P.J.S., A.G.C., and M.T.W. wrote the paper; and P.A.C. had primary responsibility for all work and final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Center for Vertebrate Genomics (P.A.C.), the Presidents Council for Cornell Women (P.A.C.), and the Bronfenbrenner Life Course Center (P.A.C.), all at Cornell University; by USDA (Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, CSREES) grant 2003-34324-13135 (subproject to P.A.C.); and by T32DK007158 (S.M.W.), National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Genotyping services were provided (to P.A.C.) by the Johns Hopkins University under federal contract no. N01-HV-48195 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The VA Normative Aging Study is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program/Epidemiology Researach and Information Center and is a research component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, or the NIH.

Supplemental Tables 1–10 are available from the “Online Supporting Material” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at http://jn.nutrition.org.

Abbreviations used: CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDR, false discovery rate; LRT, likelihood ratio test; MAF, minor allele frequency; NAS, Normative Aging Study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier.

Literature Cited

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox JT, Stover PJ. Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. Vitam Horm. 2008;79:1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selhub J. The many facets of hyperhomocysteinemia: studies from the Framingham cohorts. J Nutr. 2006;136:S1726–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Homocysteine Studies Collaboration Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2015–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis SJ, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. Meta-analysis of MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism and coronary heart disease: does totality of evidence support causal role for homocysteine and preventive potential of folate? BMJ. 2005;331:1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: evidence on causality from a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2002;325:1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homocysteine Lowering Trialists’ Collaboration Dose-dependent effects of folic acid on blood concentrations of homocysteine: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:806–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klerk M, Verhoef P, Clarke R, Blom HJ, Kok FJ, Schouten EG. MTHFR 677C→T polymorphism and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2023–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wernimont SM, Clark AG, Stover PJ, Wells MT, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, Gaziano JM, Tucker KL, Baccarelli A, Schwartz J, et al. Folate network genetic variation, plasma homocysteine, and global genomic methylation content: a genetic association study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell B, Rose CL, Damon A. The Veterans Administration longitudinal study of healthy aging. Gerontologist. 1966;6:179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker KL, Qiao N, Scott T, Rosenberg I, Spiro A III. High homocysteine and low B vitamins predict cognitive decline in aging men: the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:627–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott TE, Mendez MV, LaMorte WW, Cupples LA, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI, Menzoian JO. Are varicose veins a marker for susceptibility to coronary heart disease in men? Results from the Normative Aging Study. Ann Vasc Surg. 2004;18:459–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisskopf MG, Jain N, Nie H, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Schwartz J, Hu H. A prospective study of bone lead concentration and death from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer in the Department of Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. Circulation. 2009;120:1056–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietrich T, Jimenez M, Krall Kaye EA, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI. Age-dependent associations between chronic periodontitis/edentulism and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2008;117:1668–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim U, Peng K, Shane B, Stover PJ, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, Gaziano JM, Strawderman RL, Raiszadeh F, Selhub J, et al. Polymorphisms in cytoplasmic serine hydroxymethyltransferase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase affect the risk of cardiovascular disease in men. J Nutr. 2005;135:1989–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sesso HD, Kawachi I, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:851–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA, van den Heuvel LP, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilker EH, Alexeeff SE, Poon A, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J. Candidate genes for respiratory disease associated with markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in elderly men. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:480–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wernimont SM, Raiszadeh F, Stover PJ, Rimm EB, Hunter DJ, Tang W, Cassano PA. Polymorphisms in serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase interact to increase cardiovascular disease risk in humans. J Nutr. 2011;141:255–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herbig K, Chiang EP, Lee LR, Hills J, Shane B, Stover PJ. Cytoplasmic serine hydroxymethyltransferase mediates competition between folate-dependent deoxyribonucleotide and S-adenosylmethionine biosyntheses. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38381–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woeller CF, Fox JT, Perry C, Stover PJ. A ferritin-responsive internal ribosome entry site regulates folate metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29927–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chave KJ, Ryan TJ, Chmura SE, Galivan J. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human gamma-glutamyl hydrolase gene and characterization of promoter polymorphisms. Gene. 2003;319:167–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVos L, Chanson A, Liu Z, Ciappio ED, Parnell LD, Mason JB, Tucker KL, Crott JW. Associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in folate uptake and metabolizing genes with blood folate, homocysteine, and DNA uracil concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1149–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field MS, Anderson DD, Stover PJ. Mthfs is an essential gene in mice and a component of the purinosome. Front Genet. 2011;2:36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field MS, Anguera MC, Page R, Stover PJ. 5,10-Methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase activity is increased in tumors and modifies the efficacy of antipurine LY309887. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;481:145–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field MS, Szebenyi DM, Stover PJ. Regulation of de novo purine biosynthesis by methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase in neuroblastoma. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4215–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED, Benkovic SJ. Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells. Science. 2008;320:103–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woeller CF, Anderson DD, Szebenyi DM, Stover PJ. Evidence for small ubiquitin-like modifier-dependent nuclear import of the thymidylate biosynthesis pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17623–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson DD, Woeller CF, Stover PJ. Small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of thymidylate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1760–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson DD, Stover PJ. SHMT1 and SHMT2 are functionally redundant in nuclear de novo thymidylate biosynthesis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macfarlane AJ, Perry CA, McEntee MF, Lin DM, Stover PJ. Shmt1 heterozygosity impairs folate-dependent thymidylate synthesis capacity and modifies risk of apc(min)-mediated intestinal cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2098–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaudin AE, Abarinov EV, Noden DM, Perry CA, Chu S, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Stover PJ. Shmt1 and de novo thymidylate biosynthesis underlie folate-responsive neural tube defects in mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:789–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacques PF, Bostom AG, Williams RR, Ellison RC, Eckfeldt JH, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J, Rozen R. Relation between folate status, a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Circulation. 1996;93:7–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeiffer CM, Johnson CL, Jain RB, Yetley EA, Picciano MF, Rader JI, Fisher KD, Mulinare J, Osterloh JD. Trends in blood folate and vitamin B-12 concentrations in the United States, 1988 2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:718–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cronin S, Furie KL, Kelly PJ. Dose-related association of MTHFR 677T allele with risk of ischemic stroke: evidence from a cumulative meta-analysis. Stroke. 2005;36:1581–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Bautista LE, Sharma P. Meta-analysis of genetic studies in ischemic stroke: thirty-two genes involving approximately 18,000 cases and 58,000 controls. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1652–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai CQ, Parnell LD, Troen AM, Shen J, Caouette H, Warodomwichit D, Lee YC, Crott JW, Qiu WQ, Rosenberg IH, et al. MAT1A variants are associated with hypertension, stroke, and markers of DNA damage and are modulated by plasma vitamin B-6 and folate. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1377–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrow TA. Purification, kinetic properties, and cDNA cloning of mammalian betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22831–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doi T, Kawata T, Tadano N, Iijima T, Maekawa A. Effect of vitamin B12-deficiency on the activity of hepatic cystathionine beta-synthase in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1989;35:101–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holm PI, Bleie O, Ueland PM, Lien EA, Refsum H, Nordrehaug JE, Nygard O. Betaine as a determinant of postmethionine load total plasma homocysteine before and after B-vitamin supplementation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:301–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paré G, Chasman DI, Parker AN, Zee RR, Malarstig A, Seedorf U, Collins R, Watkins H, Hamsten A, Miletich JP, et al. Novel associations of CPS1, MUT, NOX4, and DPEP1 with plasma homocysteine in a healthy population: a genome-wide evaluation of 13 974 participants in the Women's Genome Health Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:142–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martí-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Lathyris D, Salanti G. Homocysteine lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD006612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller ER III, Juraschek S, Pastor-Barriuso R, Bazzano LA, Appel LJ, Guallar E. Meta-analysis of folic acid supplementation trials on risk of cardiovascular disease and risk interaction with baseline homocysteine levels. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:517–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.