Abstract

Unfolded protein response (UPR) is a key cellular defense mechanism associated with many human “conformational” diseases, including heart diseases, neurodegeneration and metabolic syndrome. One of the major obstacles that have hindered our further understanding of physiological UPR and its future therapeutic potential is our inability to detect and quantitate ER stress and UPR activation under physiological and pathological conditions, where ER stress is perceivably very mild. Here we describe a Phos-tag-based Western blot approach that allows for direct visualization and quantitative assessment of mild ER stress and UPR signaling, directly at the levels of UPR sensors, in various in vivo conditions. This method will likely pave the foundation for future studies on physiological UPR, aid in the diagnosis of ER-associated diseases and facilitate therapeutic strategies targeting UPR in vivo.

Keywords: IRE1α, PERK, quantitation, ER stress, Phos-tag

1. Introduction

ER homeostasis is tightly monitored by ER-to-nucleus signaling cascades termed UPR (Ron and Walter, 2007). Recent studies have linked ER stress and UPR activation to many human diseases including heart complications, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndrome (Ron and Walter, 2007; Kim et al., 2008; He et al., 2010). Indeed, chemical chaperones and antioxidants aiming to reduce ER stress and UPR activation have been shown to be effective in mouse models of obesity and type-1 diabetes (Malhotra et al., 2008; Back et al., 2009; Basseri et al., 2009). Despite recent advances, our understanding of UPR activation under physiological conditions is still at its infancy, largely due to the lack of sensitive experimental systems that can detect mild UPR sensor activation.

The underlying mechanisms of UPR signaling and activation induced by chemical drugs such as thapsigargin (Tg), tunicamycin and dithiothreitol (DTT) are becoming increasingly well-characterized (Ron and Walter, 2007). Upon ER stress, two key ER-resident transmembrane sensors, inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α) and PKR-like ER-kinase (PERK) undergo dimerization or oligomerization and trans-autophosphorylation via their C-terminal kinase domains, leading to their activation (Ron and Walter, 2007; Kim et al., 2008). Phosphorylation of IRE1α and PERK has been challenging, if not impossible, to detect under physiological conditions. The mobility-shift of IRE1α shown in many studies is very subtle on regular SDS-PAGE gels and difficult to assess. In addition, commercially-available phospho-specific antibodies against P-Ser724A IRE1α and P-Thr980 PERK do not reflect the overall phosphorylation status of the proteins. Importantly, it remains unclear whether Ser724 of IRE1α or Thr980 of PERK is indeed phosphorylated under various physiological and disease conditions.

Alternatively, many studies have used downstream events such as splicing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2a (eIF2α), induction of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and various genes involved in protein folding and ER-associated degradation (ERAD) as surrogate markers for UPR activation. This method, albeit convenient, may be confounded by the possibility of integrating signals not directly related to stress in the ER. For example, the PERK pathway of the UPR is part of the integrated stress response that consists of three other eIF2α kinases (Ron and Walter, 2007). Activation of any of these kinases leads to eIF2α phosphorylation and induction of ATF4 and CHOP. A recent study also showed that ATF4 and CHOP can be regulated translationally in a PERK-independent manner via the TLR signaling pathways (Woo et al., 2009). Furthermore, UPR target genes such as CHOP and ER chaperones can be induced by other signaling cascades such as hormones, insulin and cytokines/growth factors (Brewer et al., 1997; Miyata et al., 2008). Thus, downstream UPR targets alone are not best suited for accurate assessment and evaluation of UPR status, especially under physiological and disease settings.

As hyperphosphorylation of UPR sensors IRE1α and PERK is believed to constitute an early initiating event in UPR (Shamu and Walter, 1996; Welihinda and Kaufman, 1996), we have optimized SDS-PAGE gels incorporated with phos-tag and Mn2+, termed Phos-tag gels (Kinoshita et al., 2006), to increase the separation between the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of two UPR sensors IRE1α and PERK (Sha et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010). This powerful tool allows us to “visualize” and for the first time, quantitate ER stress in cells or tissues under physiological and pathological conditions. In this chapter, we describe detailed methods used to detect IRE1α and PERK activation and to quantitate the levels of ER stress.

2. Detecting UPR at the level of UPR sensors

2a. Preparation of the Phos-tag gels

Dissolve Phos-tag in H2O to a final concentration of 5 mM as instructed by the supplier (Phos-tag acrylamide AAL-107, Wako Pure Chemical Industries #304–93521). Add Phos-tag directly to the solution mix for the resolving gels to make standard 5% SDS-PAGE minigels (Table 1) using the Bio-Rad minigel casting systems. Final concentrations of Phos-tag in the resolving gels are 25 and 3.5 μM for IRE1α and PERK proteins, respectively. Note that no Phos-tag in the stacking gels. For optimal results, freshly prepare gels prior to the experiments. Regular gels without Phos-tag are prepared simultaneously using the same recipe minus Phos-tag and MnCl2 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Recipe for 5% Phos-tag gels.

| Components | Resolving gels (15 ml, for 2 gels) | Stacking gels (5 ml, for 2 gels) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRE1α | PERK | ||

| mQ H2O (ml) | 8.30 | 8.45 | 3.71 |

| 30% 29:1 acrylamide (ml) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.667 |

| 1.5M Tris pH8.8 (ml) | 3.75 | 3.75 | - |

| 1M Tris pH6.8 (μl) | - | - | 625 |

| 10% SDS (μl) | 150 | 150 | 50 |

| 10% ammonia persulfate (μl) | 150 | 150 | 50 |

| 5mM Phos-tag (μl) | 75 | 10.5 | - |

| 10mM MnCl2 (μl) | 75 | 10.5 | - |

| Mix gently and well | |||

| TEMED (μl) | 15 | 15 | 8 |

2b. Preparation of whole cell lysates

Lyse cells or frozen tissues in cold Tris-based lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM EDTA with protease inhibitors) for 15 min on ice and followed by sonication for 15 sec on ice. Spin lysates at top speed for 10 min at 4°C. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube and measure protein concentrations using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Adjust concentrations to 0.5~2 μg/μl using lysis buffer, H2O and 5x SDS sample buffer, boil for 5 min and spin briefly. Load 15–30 μg lysates per lane. We have noted that it is preferred to prepare lysats at relatively high concentrations and dilute them down similarly prior to the loading to ensure comparable salt concentration (See Important Tips below).

2c. Gel running and transfer

Fill the Bio-Rad mini-gel running tank with running buffer (14.4 g glycine, 3 g Tris and 1 g SDS per liter). Running conditions are 100 V for ~3 h for IRE1α and 15 mA for 15 min followed by 5 mA for 9.5 h for PERK. Then carefully place the phos-tag gel in 1 mM EDTA in transfer buffer (14.4 g glycine and 3 g Tris with 10% methanol per liter) for 10 min followed by 10 min incubation in transfer buffer. Transfer at 90–100 V for 1.5 h in the wet transfer system, where the gel and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane are held within a gel hold cassette (Bio-Rad) and soaked under transfer buffer. Upon the completion of the transfer, carefully mark the PVDF membrane to indicate the protein side and then place protein-side up in a container with Tris-based buffer (TBS) containing Tween-20 (TBST, 5.68 g NaCl, 2.4 g Tris pH7.5 and 0.1% Tween 20).

2d. Western blot

Incubate the PVDF membrane with the primary antibody diluted in 5% milk/TBST or 2% BSA/TBST (Table 2) overnight at 4°C or 1 h at room temperature followed by the secondary antibody. Wash extensively with TBST in-between. After final wash in TBST, add ECL (Pierce or Amersham) or ECL+ (Amersham) Western blot detecting reagents to the membrane for 5 or 1 min, respectively. Then place PVDF membranes in a plastic sheet cover and expose to either film or Bio-Rad ChemiDoc. Both IRE1α and PERK antibodies are very specific, even for tissues (Fig. 1) (Yang et al., 2010). Of note, endogenous IRE1α and PERK proteins in most cell types (e.g. HEK293T cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, macrophages, pancreatic acinar and β cells, hepatocytes and adipocytes) and tissues, except skeletal muscles, are readily detectable ((Yang et al., 2010) and not shown).

TABLE 2.

Information for UPR antibodies that work for endogenous proteins.

| Name (Species) | Company | Catalog/clone # | Dilutions | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRE1α | Cell Signaling | 3294/14C10 | 1:1,000 | 110kDa |

| PERK | Cell Signaling | 3192/C33E10 | 1:1,000 | 150kDa |

| P-Thr980 PERK | Cell Signaling | 3179/16F8 | 1:1,000 | 150–170kDa |

| CHOP (mousea) | Santa Cruz | sc7351/B3 | 1:500 | 30kDa |

| XBP1 | Santa Cruz | sc7160/M-186 | 1:1,000 | 54, 30kDa |

| p-eIF2α | Cell Signaling | 9721 | 1:1,000 | 38kDa |

| eIF2α | Cell Signaling | 9722 | 1:1,000 | 38kDa |

| GRP78 (goat) | Santa Cruz | sc1051/C-20 | 1:1,000 | 78kDa |

| HSP90 | Santa Cruz | sc7947/H-114 | 1:5,000 | 90kDa |

Antibody species are rabbit unless otherwise indicated.

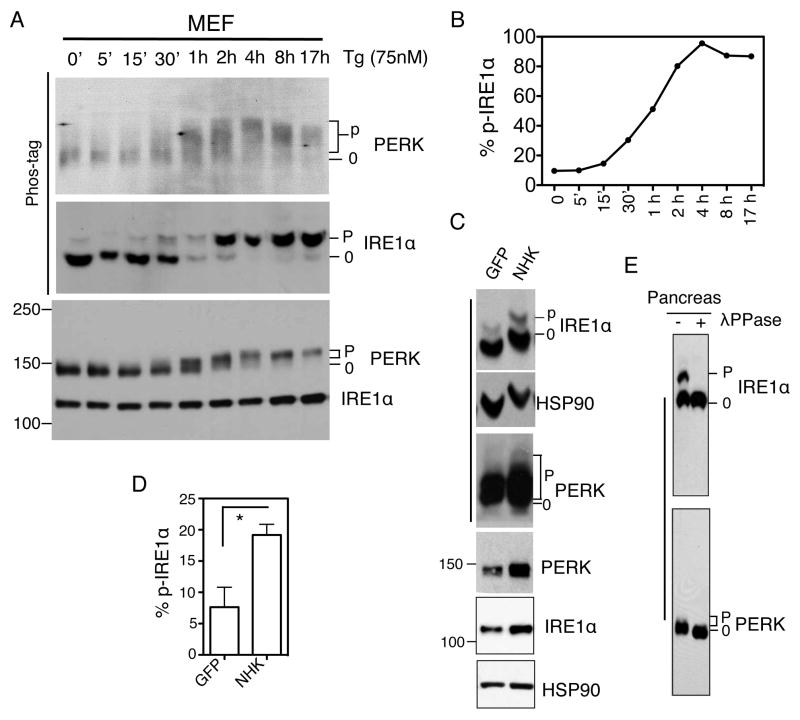

Figure 1. Visualization and quantitation of ER stress and UPR activation.

(A) Immunoblots of IRE1α and PERK proteins in Tg-treated MEFs. (B) Quantitation of percent of phosphorylated IRE1α in total IRE1α protein in Phos-tag gels shown in A. (C) Immunoblots of IRE1α and PERK in HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. NHK, the unfolded form of α1-antitrypsin; GFP, negative control plasmids. (D) Quantitation of percent of phosphorylated IRE1α in total IRE1α protein in Phos-tag gels shown in C. (E) Immunoblots of IRE1α and PERK in pancreatic lysates treated with λPPase. Phos-tag gels are indicated with a bar at the left-hand side. HSP90, a loading control. “0” refers to the non- or hypophosphorylated forms of the protein whereas “p” refers to the hyperphosphorylated forms of the protein. *, P<0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. This data is taken or modified from (Yang et al., 2010).

Strip-reprobe the IRE1α blot for HSP90 as a loading and position control. To strip, place the PVDF membrane twice in pre-warmed stripping solution (100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS and 62.5 mM Tris pH 6.8) at 50–55°C for 15 minutes with gentle shake. Rinse once in ddH2O and twice in TBST with gentle shake for 10 min each. The membrane is ready for reprobe.

3. Quantitating ER stress at the level of UPR sensors

Notably, the unique pattern of IRE1α phosphorylation in the Phos-tag gel allows for a quantitative assessment of ER stress (Fig. 1). The percent of IRE1α being phosphorylated, as % p-IRE1α in total IRE1α, can be quantitated by the Image J or Image Lab software in the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc system as described by the manufactures.

4. Detecting levels of other common UPR targets

Several of downstream UPR targets can be detected using Western blot (Sha et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010), including PERK downstream targets eIF2α, CHOP and IRE1α downstream target XBP1s. Antibody information is listed in Table 2. It is important to note that, based on our experience, these downstream markers can’t be used alone to assess UPR activation under physiological and disease settings for the reasons stated in the Introduction section, while it is fine for the conditions using pharmacological stressors.

For many cell types and tissues, nuclear extraction is required to detect CHOP and XBP1 proteins. To this end, resuspend cells in a 6-cm dish in 200 μl ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitors) followed by incubation on ice for 15 min. Add 12 μl of 10% of NP-40 to a final concentration of 0.6%. Vortex vigorously for 15 sec prior to centrifugation at top speed for 1 min. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube as the cytosolic fraction. It is recommended to wash the pellet once with 1 ml hypotonic buffer. Resuspend the pellet in 50 μl ice-cold high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM DTT) and vortex vigorously for 15 sec every 5 min for a total of 20 min. Spin at 4°C for 5 min and the supernatant is the nuclear fraction. For tissues, homogenize a pea-sized frozen tissue 20 times in 600 μl hypotonic buffer using dounce homogenizer with a loose pestle until no visible clear chunks. The rest of the procedure is the same as above for the cells. Quality of nuclear extraction can be checked using Western blot for nuclear proteins such as Lamin or CREB.

5. Important Tips

Phos-tag gel for IRE1α blot, not the PERK, is sensitive to salt concentrations with different salt concentrations leading to gel curvature (Fig. 1C). Therefore it is important to ensure that salt concentrations are comparable among samples. Additionally, the IRE1α blot in the Phos-tag gel is routinely reprobed with HSP90 (90kDa vs. 110kDa IRE1α) as a position control. For samples that are known to have very different salt concentrations, place an empty lane between them. Of note, this only affects the artistic presentation of the results, not the quantitation of percent of p-IRE1α.

For PERK, it is less important under drug-treated conditions to use Phos-tag gels as regular gels may be suffice to separate phosphorylated PERK (Fig. 1A). Nonetheless, addition of Phos-tag further increases the separation (Fig. 1A), which may be necessary under certain physiological conditions (Fig. 1C). Using this method, we recently showed that mild ER stress, with 10% IRE1α being phosphorylated, is detected during overnight fasting in pancreas, and is further increased by 3-fold upon 2 hr refeeding (Yang et al., 2010). Hence, it is important to use the method described here to detect and quantitate endogenous PERK and IRE1α activation under physiological conditions.

Inclusion of positive and phosphatase-treated controls is critical to assess the extent of ER stress. Cells treated with chemical drugs (e.g., 60–300 nM Tg, 1–5 μg/ml tunicamycin or 1 mM DTT for 2 hr) should be included as positive controls. To ensure that phosphorylation accounts for the band-shift and set the baseline for non-phosphorylated PERK, cell lysates should be treated with phosphatases (Fig. 1E). To this end, incubate ~100 μg lysates with 0.5 μl lambda phosphatase (λPPase, New England BioLabs, NEB) in 1x PMP buffer (NEB) and 1x MnCl2 at 30°C for 30 min. Stop the reaction by the addition of 5x SDS sample buffer and boil for 5min.

6. Concluding remarks

The Phos-tag-based system to quantitatively assess ER stress and UPR activation has the following major advantages (Yang et al., 2010): First, dynamic ranges of PERK and IRE1α phosphorylation can be more sensitively visualized compared to regular SDS-PAGE gels; this is particularly important for physiological UPR where ER stress can be so mild that traditional methods may no longer be accurate or reliable. Second, the major breakthrough of our method lies in the unique pattern of IRE1α phosphorylation in the Phos-tag gel which allows for a quantitative assessment of ER stress. Finally, in comparison to using commercially-available phospho-specific antibodies (e.g. P-Ser724A IRE1α and P-Thr980 PERK), our method not only provides a complete view of the overall phosphorylation status of IRE1α and PERK proteins, but also circumvents the issue of whether these specific residues are indeed phosphorylated under certain physiological conditions.

Interestingly, using this method our data revealed that many mouse tissues and cell types display constitutive basal UPR activity, presumably to counter misfolded proteins passing through the ER (Yang et al., 2010). This observation is in line with an early report demonstrating that under physiological conditions removal of these misfolded proteins in yeast requires coordinated action of UPR and ERAD (Travers et al., 2000). Taking it one step further, our data show that a fraction of mammalian IRE1α and PERK is constitutively active, with ~10% IRE1α being phosphorylated and activated (Yang et al., 2010). This low level of IRE1α activation may provide a plausible explanation for the inability of an earlier study to detect basal UPR in the XBP1s-GFP reporter mice (Iwawaki et al., 2004). We believe that the basal UPR activity is critical in providing quality control and maintaining ER homeostasis as illustrated in various UPR-deficient mouse models (Masaki et al., 1999; Reimold et al., 2000; Harding et al., 2001; Scheuner et al., 2001; Scheuner et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2007).

As ER stress is being implicated in an increasing number of human diseases, new strategies and approaches enabling a comprehensive understanding of UPR in physiological and disease settings are urgently needed to facilitate drug design targeting UPR in conformational diseases (Kim et al., 2008). The ability to directly visualize and quantitate the early activating events is an important first-step towards gaining a comprehensive view of physiological UPR. Overall, it is our hope that the method described here will aid in the diagnosis of UPR-associated diseases and improve and facilitate therapeutic strategies targeting UPR in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Qi laboratory for helpful discussions. This study was supported in part by Cornell startup fund, American Federation for Aging Research (RAG08061), American Diabetes Association (7-08-JF-47) and NIH R01DK082582 (to L.Q.). A patent has been filed regarding methods to assess physiological UPR.

References

- Back SH, Scheuner D, Han J, Song B, Ribick M, Wang J, Gildersleeve RD, Pennathur S, Kaufman RJ. Translation attenuation through eIF2alpha phosphorylation prevents oxidative stress and maintains the differentiated state in beta cells. Cell Metab. 2009;10:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basseri S, Lhotak S, Sharma AM, Austin RC. The chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyrate inhibits adipogenesis by modulating the unfolded protein response. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2486–2501. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900216-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JW, Cleveland JL, Hendershot LM. A pathway distinct from the mammalian unfolded protein response regulates expression of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones in non-stressed cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:7207–7216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Sun S, Sha H, Liu Z, Yang L, Xue Z, Chen H, Qi L. Emerging roles for XBP1, a sUPeR transcription factor. Gene Expr. 2010;15:13–25. doi: 10.3727/105221610x12819686555051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwawaki T, Akai R, Kohno K, Miura M. A transgenic mouse model for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med. 2004;10:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nm970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Xu W, Reed JC. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1013–1030. doi: 10.1038/nrd2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Miao H, Zhang K, Wolfson A, Pennathur S, Pipe SW, Kaufman RJ. Antioxidants reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and improve protein secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18525–18530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Yoshida M, Noguchi S. Targeted disruption of CRE-binding factor TREB5 gene leads to cellular necrosis in cardiac myocytes at the embryonic stage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:350–356. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata Y, Fukuhara A, Matsuda M, Komuro R, Shimomura I. Insulin induces chaperone and CHOP gene expressions in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold AM, Etkin A, Clauss I, Perkins A, Friend DS, Zhang J, Horton HF, Scott A, Orkin SH, Byrne MC, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH. An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:152–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, Song B, McEwen E, Liu C, Laybutt R, Gillespie P, Saunders T, Bonner-Weir S, Kaufman RJ. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, Vander Mierde D, Song B, Flamez D, Creemers JW, Tsukamoto K, Ribick M, Schuit FC, Kaufman RJ. Control of mRNA translation preserves endoplasmic reticulum function in beta cells and maintains glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2005;11:757–764. doi: 10.1038/nm1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha H, He Y, Chen H, Wang C, Zenno A, Shi H, Yang X, Zhang X, Qi L. The IRE1alpha-XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response is required for adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2009;9:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oligomerization and trans-phosphorylation of Ire1p (Ern1p) are required for kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18181–18187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CW, Cui D, Arellano J, Dorweiler B, Harding H, Fitzgerald KA, Ron D, Tabas I. Adaptive suppression of the ATF4-CHOP branch of the unfolded protein response by toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1473–1480. doi: 10.1038/ncb1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Sato T, Matsui T, Sato M, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A, Mori K. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6alpha and XBP1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Xue Z, He Y, Sun S, Chen H, Qi L. A Phos-tag-based method reveals the extent of physiological endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wong HN, Song B, Miller CN, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response sensor IRE1alpha is required at 2 distinct steps in B cell lymphopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:268–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Feng D, Li Y, Iida K, McGrath B, Cavener DR. PERK EIF2AK3 control of pancreatic beta cell differentiation and proliferation is required for postnatal glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]