Abstract

Myocardial fat accumulation could occur in diseased hearts. The degree of heterogeneity is unknown because accurate assessment is difficult using conventional 1H-MRS techniques in a beating heart. The purpose of this study was to characterize the distribution of intramyocellular lipid content and to determine its association with disease characteristics. 1H-MRS was performed on formalin-fixed slices of human hearts at various circumferential locations (N=55). 29% of the hearts had the highest fat content measured in the septum, followed by posterior (27%), lateral (26%), and anterior (18%) wall. Age was significantly correlated with the mean fat percentages (r2=0.12, p=0.007). Those who died from cardiovascular disease demonstrated significantly higher and more heterogeneous fat distribution than those who did not (1.62±1.1% vs 0.59±0.4%, p=0.002). In summary, septal fat content is representative of mean fat percentage. Fat content increases with age; fat distribution may be heterogeneous when associated with cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: cardiac steatosis, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, heterogeneity, ex-vivo

Introduction

Steatosis of organs such as pancreas, liver, and heart is associated with end-organ dysfunction (insulin resistance/diabetes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, cardiomyopathy/left ventricular dysfunction respectively) (1–5). Normally, most triglyceride (TG) is stored in adipocytes. Only a very small amount is stored in nonadipocyte tissue and this amount is normally closely regulated (4). Myocardial TG accumulation, “myocardial lipotoxicity”, is the net result of excessive plasma nonesterified fatty acid uptake in relation to oxidative fatty acid requirements (6,7). Excessive lipolysis and lipotoxic injury to cardiomyocytes are associated with abnormal diastolic and systolic function in animal models (8). The accumulation of neutral lipids, known as myocardial steatosis, produces lipotoxic substances that result in oxidative stress and can cause apoptosis.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) has proven to be a valuable noninvasive tool to measure myocardial TG content in humans (9–12). 1H-MRS has allowed investigators to detect the accumulation of triglycerides in the hearts of patients with impaired glucose tolerance, as well as those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (9) and obesity. 1H-MRS allows detection of a number of metabolites, including creatine, lactate, choline, and various TG fatty acids. Compared to other nuclei such as 23Na (sodium), 13C (carbon), and 31P (phosphorus), proton (1H) holds the greatest potential of clinical applications for the assessment of cardiac disease because of its high concentration as well as MR sensitivity. Most of the reported 1H-MRS studies were performed with electrocardiograph (ECG) gating with breath-holding or synchronized with respiratory cycle at end-exhalation. Current technical limitations restrict 1H-MRS to the interventricular septum where cardiac motion is moderate and voxel placement is more precise. For the classical expectations of physiological myocardial TG accumulation, not the encapsulated fatty mass such as cardiac lipoma or fibro-fatty replacement in healed myocardial infarction, it is generally assumed that the distribution will be homogeneous throughout the heart tissue. However, little is known of the degree of heterogeneity of intracellular fat within the heart, mainly because of the lack of spatial precision of the methods for reliable measurements.

Accurate characterization of myocardial TG distribution is difficult to achieve using conventional 1H-MRS techniques in a beating heart. In practice, only septal fat is measured and it is unknown if septal fat is representative of overall myocardial fat. In the current study, we explored the extent, and distribution of myocardial neutral lipid in fixed human heart slices. The ex-vivo assessments circumvent the putative methodological pitfalls of 1H-MRS in in-vivo experiments. We evaluated data collected using 1H-MRS at various positions of each specimen and correlated these features with the patients’ demographics and the presence of cardiovascular disease.

Materials and Methods

Proton MR Spectroscopy

Heart specimens from 55 human subjects were scanned on a 3.0T MR scanner (Verio, Siemens). The institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins University approved all protocols and experimental procedures for using decedent’s protected health information in this research. Eleven specimens were from native transplant hearts and 44 specimens were obtained postmortem. Specimens were fixed for at least one week in neutral buffered formalin, and then were removed from the formalin, rinsed with tap water, and immersed in tap water for 24 hours before scanning. The tissue specimens consisted of cross-sectional slices of the heart, ranging from 4 to 10 cm in diameter, with a thickness of 1–2 cm. Seven to nine slices were tightly stacked centrally in a plastic jar that was filled with tap water. The jar was then positioned centrally in a commercially available RF headcoil. Scout imaging and gradient echo sequences were used to locate the position of each slice, and the location of the scanned regions in each slice. Two to four positions (septum, lateral wall, posterior wall, and anterior wall, depending on tissue availability), within each slice were scanned with 1H-MRS. We avoided those regions with apparent scars (gross examination by a pathologist, confirmed by histology) to assess the amount of neutral lipid in the myocardium. We were also careful to avoid epicardial fat when we adjusted the boundaries of the regions that we scanned. Myocardial fat MRS were collected in 197 regions from 55 human subjects, of which 55 regions were from septum, 44 from lateral wall, 51 from posterior wall, and 47 from anterior wall. 49 slices had at least three regions scanned and 6 slices had only two regions scanned.

Myocardial 1H-MRS spectra were obtained using a single voxel point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS), TR/TE =3000ms/35ms, voxel size 6–8cc. For reliable measurement of the low fat signals with adequate receiver gain and also to prevent the distorted spectrum due to digitization noise, one spectrum (24 averages) was recorded with WET water suppression with 1,024 data points collected over a 1,000 Hz spectral width. Another spectrum (24 averages) was recorded with the water suppression RF pulse power set to zero. Outer volume suppression using saturation bands was applied to exclude the lipids from epicardial fat.

Histology

After scanning cross-sectional slices of the hearts that had been fixed in 10% buffered formalin, sections from the center of the regions that had been scanned with MRS and found to have heterogeneous fat distributions were submitted for routine histology in 10% buffered formalin. The criteria for histologic exanimation were: the heart slice 1) had all four regions evaluated by MRS; 2) three of four regions were generally in good agreement with less than 1% fat and one region had 2% or higher fat percentage, or more than twice the average of the other three regions. There was a possibility that the exceptionally high measured fat was due to perivascular or interstitial fat in one region but not in others. To exclude regions that contained large amounts of interstitial or perivascular fat from the analysis of heterogeneous fat distribution, high fat regions of the heart slices that met the above criteria would be cut into approximately 25×20×3 mm sections and evaluated by histology. The sections were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin using standard histologic processing. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined by light microscopy.

Analysis

Spectral analysis was done offline using Java-based MR user interface (jMRUI v.3.0 software; developed by A. van den Boogaart, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) (13). Water and fat signals were fitted by the Advanced Method for Accurate Robust and Efficient Spectral fitting (AMARES) (14) with the assumption of Gaussian distribution Resonance frequency estimates of lipids at 0.9, 1.3 and 2.1 ppm were fitted, but only amplitudes at 0.9 and 1.3 ppm were summed to quantify intramyocardial fat content and related to AMARES estimated water at 4.7 ppm in unsuppressed spectra (15,16). 2.1 ppm peak is a mixture of polyolefinic/monolefinic CH2 groups and is not intramyocardial fat. Myocardial fat percentage was calculated as the ratio of myocardial lipids to water content and reported as a percentage. Mean fat percentage was averaged from all available scanning locations on each heart slice. The mean fat percentage of all scanning positions (septum, lateral, posterior, and anterior wall) on each slice was calculated. To characterize the heterogeneity of myocardial fat distribution, we reported the percentage of the region that demonstrated the highest as well as the lowest fat content. We also calculated the variability of fat percentage based on the standard deviation of the mean fat measurement in each specimen. The higher the standard deviation (i.e. fat percent variability), the greater the heterogeneity of the fat distribution. Paired student t-test was used to compare the difference among the various fat percentages (i.e. septum, highest, mean and lowest) measured on each slice.

Demographic data were extracted from the medical records. Baseline characteristics of the study population are reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for discrete variables. Unadjusted comparisons across gender, race, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (defined as body mass index, BMI≥30, and BMI≤25 as lean) were done by unpaired t-tests assuming unequal variance (Welch correction) for continuous variables and with χ2-tests for dichotomous variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient and linear regression analysis were used to examine the association between the highest as well as mean fat percentages with those measured in the septum, and with age. Studies were also stratified by the disease characteristics for the comparison of fat percent and distribution analysis. Statistical significance was defined at the p<0.05 level. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Chicago, Illinois).

Results

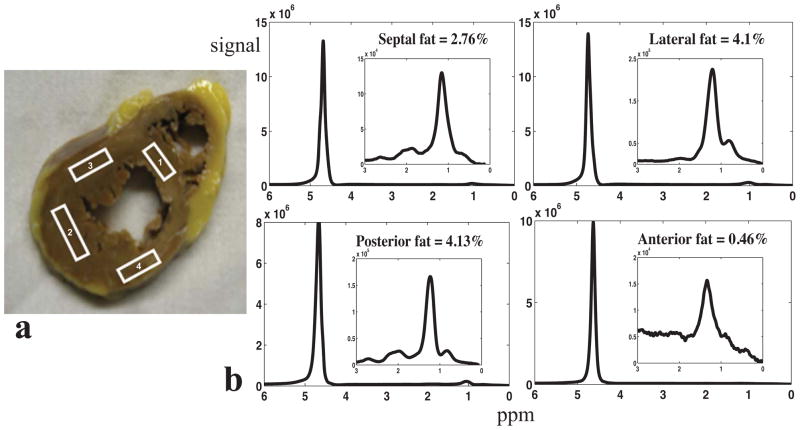

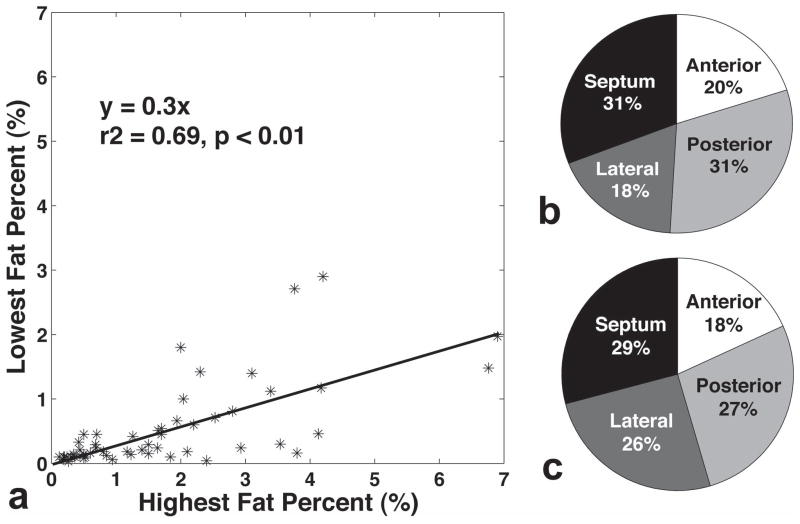

All data from 197 regions were analyzed and included in the following statistical analysis. No data were excluded because of large amounts of interstitial or perivascular fat, following histology analysis. 1H-MRS voxel placement is illustrated in Figure 1a, as well as representative spectra of four regions shown in Figure 1b. Scatter plots of the highest and the lowest fat measured on each slice is depicted in Figure 2a. These two values were strongly correlated. In a few instances, the highest and lowest values were similar indicating relatively homogeneous fat distribution, but in hearts with the highest fat percentages, the highest fat percentage was threefold higher than the lowest fat percentage. Figure 2b and 2c show the percentage of the regions with the lowest and highest fat content in each specimen, respectively. 31% of the slices have the lowest fat exhibited in the septum as well as the posterior wall, followed by anterior (20%), and lateral wall (18%). Meanwhile, 29% of the slices have the highest fat content measured in the septum, followed by posterior wall (27%), lateral wall (26%), and anterior wall (18%).

Figure 1.

(a) Representative 1H-MRS voxel placement: 1. Septum, 2. Lateral wall, 3. Posterior wall, and 4. Anterior wall.(b)Water spectra of different regions with the corresponding water-suppressed fat spectra in the inset.

Figure 2.

The highest fat percentage was significantly higher than the lowest fat percentage measured in each slice while strong association was also observed (a). The percentages of the regions with the lowest (b) and the highest (c) fat contents in each specimen (pie charts).

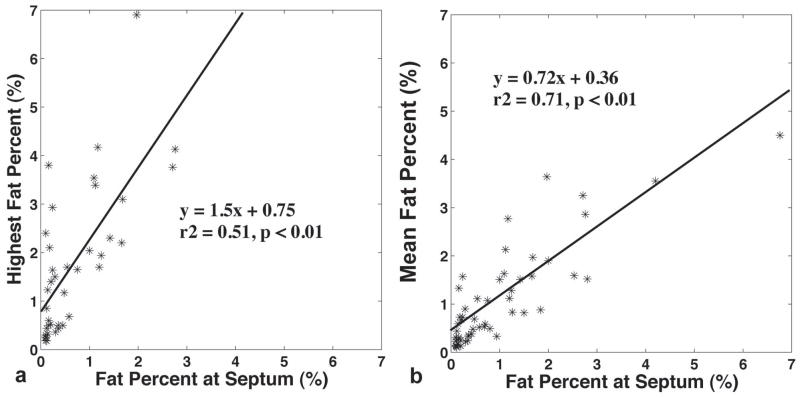

The correlations of the highest and the mean fat percentages with those measured from the septum in each specimen are demonstrated in Figure 3. To prevent bias, sixteen specimens in which the highest fat content coincided with septal fat were excluded from the comparison in Figure 3a. The mean fat calculation in Figure 3b took all measurements into consideration. Both the highest and averaged fat percentages exhibited significant associations with those percentages estimated from the septum. However, the septal fat was significantly lower than the highest fat (0.96±0.95% vs. 1.72±1.56%, p<0.01), but was comparable to the mean fat percentage (1.05±1.02%, p=0.32) measured on the same slice.

Figure 3.

The correlations of the highest (a) and the mean fat (b) percents with those measured from the septum in each slice. Both assessments exhibited significant associations with those estimated from the septum.

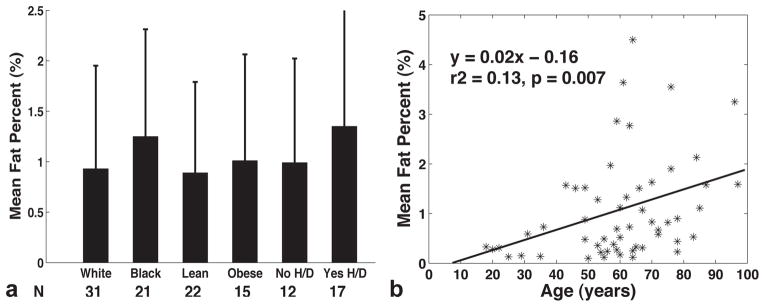

The main patient demographics stratified by gender are summarized in Table 1. The mean age overall was 60 ± 18 years (18 to 97 years). No significant demographic differences were present between men and women. Figure 4a compares the mean fat percentages between races (White versus Black), BMI (lean versus obese), with both hypertension and diabetes or without both. In summary, black, obese, and those with both hypertension and diabetes displayed higher fat contents than their corresponding control groups. Mean fat content was 1.25±1.2% for diabetic hearts (N=14) and 0.98±0.96% for nondiabetic hearts (N=41, p=0.46). The same trend was found either using highest fat percent or fat measured just from the septum for comparison. Age was significantly correlated with the mean fat percent (Figure 4b, r2=0.13, p=0.007). Such correlation remained significant when the septal fat was used in the regression model (r2=0.1, p=0.02), but not with the highest fat percent (p=0.07). The variability of fat percent was not associated with age (p=0.6).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Men (N=27) | Women (N=28) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61±19 | 58±17 |

| Weight (kg) | 89±18 | 80±20 |

| BMI | 27±4 | 29±7 |

| Caucasian/Africa/Other | 18/7/2 | 13/14/1 |

| Hypertension | 17 (63%) | 19 (68%) |

| Diabetes | 6(22%) | 8(29%) |

| Mean fat percent | 1.02±0.95 | 1.08±1.09 |

Figure 4.

(a) Comparison of the mean fat percentages between races (White: 0.93±1.0; Black: 1.25±1.0), BMI (Lean: 0.89±0.9; Obese: 1.01±1.0), with both hypertension and diabetes (0.99±1.0) or with neither (1.35±1.2). None of the difference was statistically significant between groups. (b) Mean myocardial fat percent correlated significantly with age (p=0.007).

Table 2 lists the disease categories, their corresponding ages, the averaged fat percentage from all specimens, and the fat percent variability (i.e the averaged standard deviation of the mean fat percentage) in each group. Transplant hearts (G1) had the youngest age as well as the lowest fat percentage. Dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were two major indications for heart transplant. In contrast, those who died from cardiovascular disease (G2), including acute myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, and stroke, were significantly older in age (p=0.002) and had a higher fat content (p=0.0004) than those of G1. Groups 3 and 4 represent two explicit disease populations, myeloid leukemia and human immune-deficiency virus infection (HIV). These two groups were distinct because of their exceptionally high fat contents compared to those of other groups, and it is worth noting that none of these subjects died from cardiovascular disease. Since the sample size in both groups was small (N=3 in each), we did not compare to other groups for statistical difference. The last group (G5, other) was for those who died from non-cardiovascular related disease, mainly lung disease, cancer, and renal failure. G5 had significantly lower fat compared to that of G2 (p=0.002). There was no age difference between these two groups. The fat percentage in G2 remained significantly higher than in G1 or G5 for the highest fat percentages. The heterogeneous distribution of myocardial fat was greater in the disease groups with the highest amount of fat (Table 2, Fat distribution Variability). G2 (cardiovascular disease group) demonstrated higher variability than G1 and G5 (p=0.03 and 0.02, respectively).

Table 2.

Myocardial fat percentages stratified by disease category.

| Group | N/Women | Age (years) | Mean fat percent (%) | Fat distribution Variability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transplant | 11/5 | 43±21 | 0.39±0.4 | 0.34±0.3 |

| 2. Cardiovascular disease | 17/8 | 69±14 | 1.62±1.1 | 0.78±0.6 |

| 3. Leukemia | 3/1 | 56±12 | 1.83±0.9 | 1.15±0.6 |

| 4. Human immune-deficiency virus (HIV) | 3/0 | 57±7 | 2.67±1.5 | 1.42±1.0 |

| 5. Other: Lung disease, cancer, renal failure. | 21/11 | 61±16 | 0.59±0.4 | 0.36±0.3 |

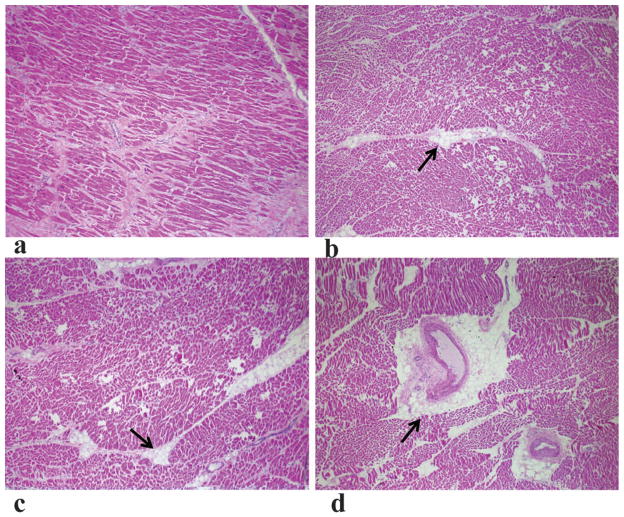

Four heart slices were cut into a total of ten tissue sections and examined by histology (1–3 sections from each slice). Figure 5 shows representative tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Most of sections have virtually no interstitial lipid droplets (Figure 5a) or minimal lipid accumulation around small arteries and arterioles (Figure 5b, c). Figure 5d shows extracellular lipid around a penetrating coronary artery branch, which could contribute to the higher fat percentages in some regions.

Figure 5.

Representative tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Arrows denote extracellular lipid droplets. (a) Virtually no lipid droplets were seen anywhere in the section. (b, c) Lipid deposition around small arteries. (d) Lipid deposition around a penetrating coronary artery branch.

Discussion

The findings of the current study suggest that myocardial fat deposition could be heterogeneous and the variability greatly depends on the genre of disease. The interventricular septum appeared to be the leanest muscle, because 31% of the samples had the lowest fat content measured in this region. The results from the septum might underestimate the severity of cardiolipotoxicity; since only 29% of the highest fat was exhibited in the septum (Figure 2c). However, when considering the strong association between septal and highest fat measurements, our studies did not totally rule out the applicability of using septal fat as an index for the existence of myocardial steatosis. Assessment of the septum is quite representative of fat content overall (Figure 3b, strong association and comparable fat percents between septum and mean fat).

The average fat percent from all regions in all samples was 1.05% which was comparable to those measured in type 2 diabetes mellitus (1.06%) reported by McGavock et al (9). Our study cohort consisted of various disease groups and cannot be considered as normal. The heterogeneity of lipid accumulation appears to be more pronounced in some diseases than in others. In addition to the high fat percentage measured in the cardiovascular disease group (G2, Table 2), there was also exceptionally heterogeneous fat distribution. Impaired cardiac function, both systolic and diastolic (8,11,12,17,18), has been shown to be correlated with increased intramyocellular lipid accumulation. It can be postulated that cardiovascular disease might lead to weakening of the muscle, resulting in fibro-fatty hearts. Such accumulation could be a multi-year process before it becomes manifest. This is suggested by the correlation between age and mean fat percentage in our study. Interestingly, we have also observed evidence of prominent fat accumulation in the hearts from those with leukemia and HIV. Nevertheless, with only three cases in each group, further research is required to validate and elucidate such relationships.

The storing of excess lipids in human cardiac myocytes is an early manifestation in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (9,17). Myocardial fat content has also been reported to be elevated within the myocardium with obesity, both in animals (19) and humans (9,20). Our results parallel these findings, that myocardial steatosis was increased in the diabetic and obese hearts, but the statistical significance was diminished, presumably by confounding variables in our study population.

The localized proton spectroscopy was used in the study because the technique is commercially available and has proven to be accurate as well as highly reproducible (11,16). 1H-MRS is the current non-invasive method of choice for in-vivo myocardial fat measurements and is considered as a reference for imaging methods such as chemical-shift imaging (21,22). While the sensitivity and specificity of 2D (in-phase/out-of-phase) imaging for the detection of hepatic steatosis is very high (23,24), its application to cardiac steatosis requires more elaboration of the imaging acquisition and bias correction due to its low fat content (25). The emerging chemical-shift based methods (26–28) hold the greatest promise for non-invasive quantification of fatty infiltration with high spatial resolution and volumetric coverage of the heart. With an accurate non-invasive imaging method, the need for MRS or even biopsy to evaluate steatosis will be reduced or perhaps eliminated, and replaced with a more comprehensive measure of steatosis.

Certain limitations to the present study should be acknowledged. Biochemical assays were not performed for the evaluation of myocardial fat accumulation in our specimens. Validation by quantitative assay would have further substantiated the current observations. However, the correlation between 1H-MRS and biochemical measurements has been high in previous work (29,30). Both 1H-MRS measured water and fat signals are affected by T2. The fat percentage will be overestimated because the fat T2 value is longer than that of water and the overestimation is increased with higher fat content. An accurate T2 correction requires both T2s of water and fat to be measured in each specimen which were not performed in our study. Nevertheless, we have simulated T2 bias using T2s reported by Szczepaniak et al (29) and found only a 15% increase when the true fat percent is as high as 5%. Considering the low fat content in cardiac steatosis, T2 bias might not be a major concern and should not alter the conclusions. The clinical characteristics could be stratified by chronic versus acute disease, which represents different metabolic states. For example, a person with leukemia or lung cancer dies often due to overwhelming infection and may be cachectic, in contrast to those with acute myocardial infarction or stroke. The difficulty of assessing the complete medical records hindered the authors to evaluate the status. We have properly accounted for the heart tissue fixation by removing the specimens from formalin and maintaining them in tap water for 24 hours before scanning. However, whether the exposure either to formalin or the rinsing would affect the deposition of myocardial fat in the heart is not clear. Our results showing measureable fat and reasonable amount of fat contents might indicate that the myocardial lipid is relatively well preserved. Furthermore, fixation is uniform and would not contribute to the heterogeneity we observed.

Despite these limitations, the present study has exposed an important issue of myocardial steatosis. The supportive evidence in our ex-vivo studies demonstrated that the myocardial fat distribution could be heterogeneous. The heterogeneity is increased with the presence of cardiovascular disease in the aging hearts.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIH grant R21HL098827.

References

- 1.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Ford DA, Hsu FF, Garcia R, Herrero P, Saffitz JE, Schaffer JE. A novel mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(7):813–822. doi: 10.1172/JCI10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirose H, Lee YH, Inman LR, Nagasawa Y, Johnson JH, Unger RH. Defective fatty acid-mediated beta-cell compensation in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Pathogenic implications for obesity-dependent diabetes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(10):5633–5637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGavock JM, Victor RG, Unger RH, Szczepaniak LS. Adiposity of the heart, revisited. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szczepaniak LS, Victor RG, Orci L, Unger RH. Forgotten but not gone: the rediscovery of fatty heart, the most common unrecognized disease in America. Circ Res. 2007;101(8):759–767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffer JE. Lipotoxicity: when tissues overeat. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14(3):281–287. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unger RH, Orci L. Lipoapoptosis: its mechanism and its diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585(2–3):202–212. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christoffersen C, Bollano E, Lindegaard ML, Bartels ED, Goetze JP, Andersen CB, Nielsen LB. Cardiac lipid accumulation associated with diastolic dysfunction in obese mice. Endocrinology. 2003;144(8):3483–3490. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGavock JM, Lingvay I, Zib I, Tillery T, Salas N, Unger R, Levine BD, Raskin P, Victor RG, Szczepaniak LS. Cardiac steatosis in diabetes mellitus: a 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation. 2007;116(10):1170–1175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.645614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reingold JS, McGavock JM, Kaka S, Tillery T, Victor RG, Szczepaniak LS. Determination of triglyceride in the human myocardium by magnetic resonance spectroscopy: reproducibility and sensitivity of the method. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(5):E935–939. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00095.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins RL, Metzger GJ, Sartoni-D’Ambrosia G, Arbique D, Vongpatanasin W, Unger R, Victor RG. Myocardial triglycerides and systolic function in humans: in vivo evaluation by localized proton spectroscopy and cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):417–423. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Meer RW, Rijzewijk LJ, Diamant M, Hammer S, Schar M, Bax JJ, Smit JW, Romijn JA, de Roos A, Lamb HJ. The ageing male heart: myocardial triglyceride content as independent predictor of diastolic function. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(12):1516–1522. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naressi A, Couturier C, Devos JM, Janssen M, Mangeat C, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D. Java-based graphical user interface for the MRUI quantitation package. Magma. 2001;12(2–3):141–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02668096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanhamme L, van den Boogaart A, Van Huffel S. Improved method for accurate and efficient quantification of MRS data with use of prior knowledge. J Magn Reson. 1997;129(1):35–43. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Meer RW, Hammer S, Smit JW, Frolich M, Bax JJ, Diamant M, Rijzewijk LJ, de Roos A, Romijn JA, Lamb HJ. Short-term caloric restriction induces accumulation of myocardial triglycerides and decreases left ventricular diastolic function in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):2849–2853. doi: 10.2337/db07-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Meer RW, Doornbos J, Kozerke S, Schar M, Bax JJ, Hammer S, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Diamant M, Rijzewijk LJ, de Roos A, Lamb HJ. Metabolic imaging of myocardial triglyceride content: reproducibility of 1H MR spectroscopy with respiratory navigator gating in volunteers. Radiology. 2007;245(1):251–257. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijzewijk LJ, van der Meer RW, Smit JW, Diamant M, Bax JJ, Hammer S, Romijn JA, de Roos A, Lamb HJ. Myocardial steatosis is an independent predictor of diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(22):1793–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindsey JB, Marso SP. Steatosis and diastolic dysfunction: the skinny on myocardial fat. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(22):1800–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Hirose H, Zhou YT, Esser V, McGarry JD, Unger RH. Increased lipogenic capacity of the islets of obese rats: a role in the pathogenesis of NIDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46(3):408–413. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kankaanpaa M, Lehto HR, Parkka JP, Komu M, Viljanen A, Ferrannini E, Knuuti J, Nuutila P, Parkkola R, Iozzo P. Myocardial triglyceride content and epicardial fat mass in human obesity: relationship to left ventricular function and serum free fatty acid levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4689–4695. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard CP, Liney GP, Manton DJ, Turnbull LW, Langton CM. Comparison of fat quantification methods: a phantom study at 3. 0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(1):192–197. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu HH, Kim HW, Nayak KS, Goran MI. Comparison of fat-water MRI and single-voxel MRS in the assessment of hepatic and pancreatic fat fractions in humans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(4):841–847. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin J, Sentis M, Puig J, Rue M, Falco J, Donoso L, Zidan A. Comparison of in-phase and opposed-phase GRE and conventional SE MR pulse sequences in T1-weighted imaging of liver lesions. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20(6):890–897. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegelman ES, Rosen MA. Imaging of hepatic steatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21(1):71–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu CY, Redheuil A, Ouwerkerk R, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Myocardial fat quantification in humans: Evaluation by two-point water-fat imaging and localized proton spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):892–901. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernando D, Haldar JP, Sutton BP, Ma J, Kellman P, Liang ZP. Joint estimation of water/fat images and field inhomogeneity map. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(3):571–580. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellman P, Hernando D, Shah S, Zuehlsdorff S, Jerecic R, Mancini C, Liang ZP, Arai AE. Multiecho dixon fat and water separation method for detecting fibrofatty infiltration in the myocardium. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(1):215–221. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeder SB, Wen Z, Yu H, Pineda AR, Gold GE, Markl M, Pelc NJ. Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szczepaniak LS, Babcock EE, Schick F, Dobbins RL, Garg A, Burns DK, McGarry JD, Stein DT. Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by H spectroscopy: validation in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 1):E977–989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madden MC, Van Winkle WB, Kirk K, Pike MM, Pohost GM, Wolkowicz PE. 1H-NMR spectroscopy can accurately quantitate the lipolysis and oxidation of cardiac triacylglycerols. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1169(2):176–182. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90203-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]