Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether caffeine intake is associated with urinary incontinence (UI) among Japanese adults.

Methods

A total of 683 men and 298 women aged 40 to 75 years were recruited from the community in middle and southern Japan. A validated food frequency questionnaire was administered face-to-face to obtain information on dietary intake and habitual beverage consumption. Urinary incontinence status was ascertained using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form.

Results

Mean daily caffeine intake was found to be similar between incontinent subjects (men 120 mg, women 94 mg) and others without the condition (men 106 mg, women 103 mg), p=0.33 for men and p=0.44 for women. The slight increases in risk of UI at the highest level of caffeine intake were not significant after adjusting for confounding factors. The adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) were 1.36 (0.65 to 2.88) and 1.12 (0.57 to 2.22) for men and women, respectively.

Conclusions

No association was evident between caffeine intake and UI in middle-aged and older Japanese adults. Further studies are required to confirm the effect of caffeine in the prevention of UI.

Keywords: Caffeine, Case-control studies, Risk factors, Urinary incontinence, Urinary tract symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common and costly problem affecting middle-aged and older people. The International Continence Society has defined UI as "a condition where involuntary loss of urine is a social or hygienic problem and is objectively demonstrable" [1]. The prevalence of UI is known to be higher for women and increases with age, obesity and smoking [1]. Diet also plays an important role, with potatoes and carbonated drinks being linked to urinary problems [2,3], and higher meat consumption can increase the risk of lower urinary tract symptoms [4]. Dietary nutrients, such as total fat, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, zinc, and vitamin B12 are all positively associated with UI [5].

The development of UI symptoms can also be affected by caffeine intake. A recent cohort study of 65 176 women in the USA reported that the incidence of UI was positively associated with caffeine ingestion, and a high level of intake increased the risk of urge but not stress or mixed incontinence [6]. A case-control study of 259 women found an elevated risk of urge incontinence for those having 400 mg of caffeine per day when compared to minimal intake of less than 100 mg per day [7]. An intervention trial involving 135 American women showed that decreased caffeine intake by the treatment group led to a reduction in frequency of UI [8].

In the literature, focus has been directed to female UI whereas investigation on incontinent males is scant. The aim of this study was to ascertain the hypothesis of positive association between UI and caffeine intake among middle-aged and older Japanese adults. The finding may have important implications for the prevention and treatment of UI.

METHODS

I. Subjects

Seven hundred men and three hundred women aged 40 to 75 years were recruited from the community in middle and southern Japan. This convenience sample of subjects was interviewed by the first author at shopping malls, community centres or when they undertook health checks at hospital outpatient clinics. A quota sampling scheme was adopted and data collection was conducted over 18 months. Subjects were excluded if they were non-residents or outside the desired age range. A total of 683 eligible men and 298 women were available for analysis after excluding consented participants with missing personal details. No statistically significant differences were found between the included and the excluded subjects in terms of main demographic variables. The purpose and procedure were explained to each participant before obtaining their written consent. Confidentiality and the right to withdraw without prejudice were ensured and maintained throughout the interview. Approval of the project protocol was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the researchers' institution in conformity to the Helsinki Declaration.

II. Instruments

A structured questionnaire incorporating the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) [9] was administered face-to-face to assess UI status. The ICIQ-SF is a robust measure for evaluating the severity of urinary loss and condition-specific quality of life. The reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the instrument have been established [9,10]. It consisted of three components to determine frequency, quantity, and impact of urine leakage. Frequency was categorized into 0 (never), 1 (about once a week or less often), 2 (two or three times a week), 3 (about once a day), 4 (several times a day), and 5 (all the time). UI was considered present for those subjects within categories 1 to 5. Quantity was measured from 0 (none), 2 (a small amount), 4 (a moderate amount) to 6 (a large amount). The impact of leakage on daily life was scored on an incremental scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (a great deal). The circumstances of incontinence were recorded via a separate self-diagnostic item, with urge incontinence defined as 'leaks before you can get to the toilet', stress incontinence defined as either 'leaks when you cough or sneeze' or 'leaks when you are physically active or exercising', whereas the combinations of these symptoms were regarded as mixed incontinence. Other incontinence referred to 'leaks when you are asleep', 'when you have finished urinating and are dressed', 'for no obvious reason', and 'all the time'.

Physical activity in daily life was measured in terms of metabolic equivalent tasks (MET) using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form [11]. The questionnaire comprised nine items about time spent during the last seven days: in walking (frequency, duration and pace), in vigorous activity (frequency and duration), in moderate activity (frequency and duration) and in sitting (duration on weekday and weekend) [11,12].

Information on habitual beverage consumption was obtained using a food frequency questionnaire developed by the Japan Epidemiological Association [13], with validity and reproducibility being established for Japanese adults [14]. For each beverage type, participants were asked to report the average quantity consumed and frequency of intake in nine levels ranging from 'almost never' to 'ten or more cups per day'. Daily fluid intake (mL) was calculated by summing the amounts from all beverages including water and alcoholic drinks (sake, shochu, beer, whisky and wine). The reference recall for beverage consumption variables was set at five years before interview because estimation beyond five years would be difficult.

The final part of the structured questionnaire collected information on demographic and lifestyle characteristics including age, weight, height, marital status, education level, location of residence, retirement status, smoking, as well as health conditions (hypertension, ischemic stroke, diabetes mellitus, depression and cancer). On average each interview took about 45 minutes to complete.

III. Statistical Analysis

For each subject, total caffeine intake (mg/d) was obtained by adding the corresponding quantities from coffee, black tea, green tea, oolong tea, soda and chocolate consumption. The caffeine contents of these items were taken from the Japanese standard tables of food composition: 0.4 mg/mL (coffee), 0.08 mg/mL (black tea), 0.03 mg/mL (green tea), 0.03 mg/mL (oolong tea), 0.1 mg/mL (soda), and 0.4 mg/g (chocolate) [15].

Subjects with UI were first identified on the basis of positive outcomes to the ICIQ-SF questions. After applying descriptive statistics to summarise sample characteristics by UI status, comparisons between the two groups were made using chi-square and t tests. Men and women were analysed separately in view of their differences in pathophysioloical mechanisms for UI. Unconditional logistic regression analyses were then performed to determine the association between caffeine intake and the prevalence of UI. Each regression model accounted for the effects of age, body mass index (BMI), physical activity (MET), daily total fluid intake, smoking status (never smoker, ex-smoker or current smoker), alcohol drinking (non-drinker, drinker) and presence of co-morbidity. These variables were considered potential confounders from the literature. All statistical analyses were undertaken using the SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

The prevalence of UI was 7.2% (n=49) for men and 27.5% (n=82) for women based on the ICIQ-SF criterion. Urine leakage among the incontinent subjects was typically "a small amount" and occurred once a week or less often. The distribution of UI type was: stress (men, 14.3%; women, 70.7%), urge (men, 53.1%; women, 14.6%), mixed (men, 4.1%; women, 11%) and other (men, 28.6%; women, 3.7%). Only a few of the incontinent subjects considered the condition to have great interference on their daily life.

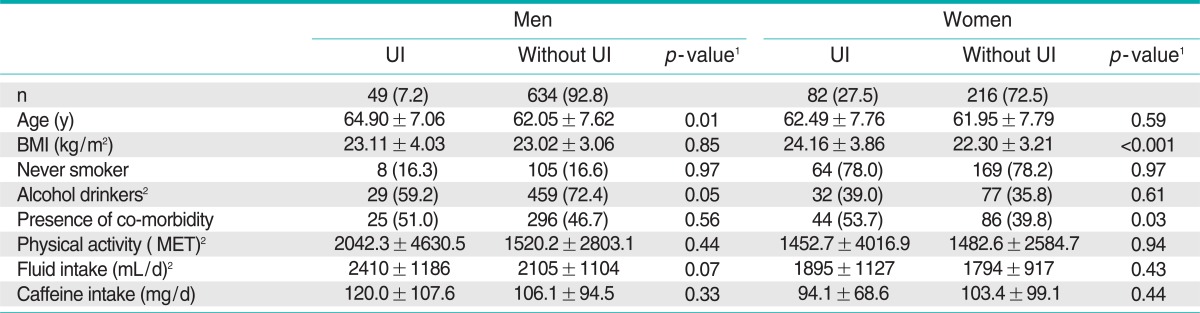

Table 1 compares the characteristics of Japanese adults with and without UI by gender. Men with UI were about three years older on average and less likely to drink alcohol than others without the condition, while the incontinent women had significantly higher BMI (p<0.001) and prevalence of co-morbidity (p=0.031) than their symptom-free counterparts. Coffee drinking contributed to 83% of the total caffeine intake by the participants, whereas other sources contributed relatively little to caffeine intake (black tea 1%, green tea 9%, oolong tea 4%, soda 2%, and chocolate 1%). However, the amount of caffeine intake was not significantly different between subjects with and without UI for both genders (p=0.33 for men and p=0.44 for women).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Japanese adults by gender and urinary incontinence status

Data are presented as mean±SD or n (%).

UI, urinary incontinence; BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent tasks.

1Based on chi-square or t-test.

2Missing data present.

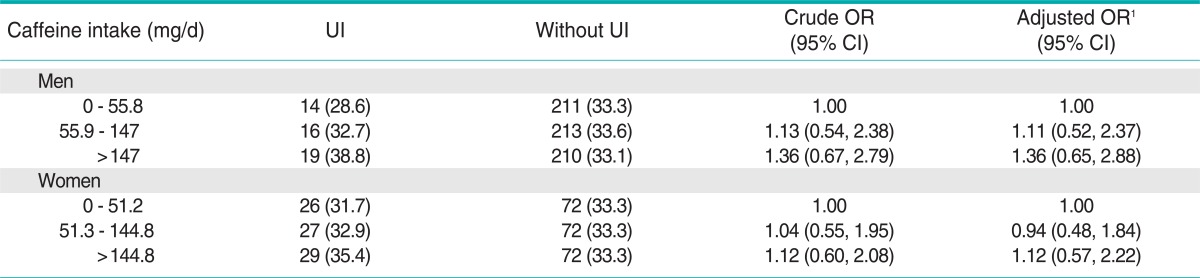

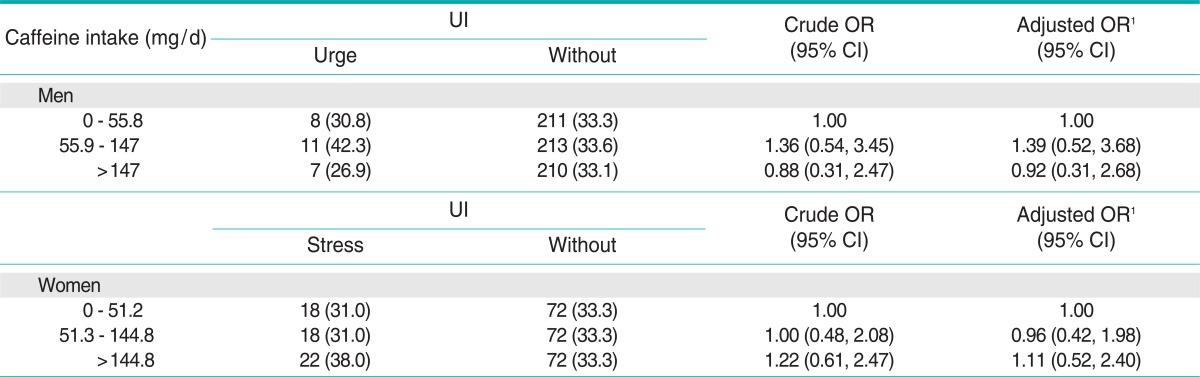

Table 2 presents the logistic regression results. Caffeine intake was positively associated with the prevalence of UI, though the small increases in risk at the highest level of intake did not reach statistical significance. To assess the sensitivity of the analyses, separate investigations were conducted for incontinence subtypes (stress for women and urge for men). Again little adverse effect due to caffeine intake was evident and the corresponding results are given in Table 3.

Table 2.

Association between caffeine intake and urinary incontinence in Japanese adults

Data are presented as n (%).

UI, urinary incontinence; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

1Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol drinking, physical activity level, total fluid intake and presence of co-morbidity.

Table 3.

Association between caffeine intake and urge incontinence in Japanese men and stress incontinence in Japanese women

Data are presented as n (%).

UI, urinary incontinence; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

1Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol drinking, physical activity level, total fluid intake and presence of co-morbidity.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides the first report investigating the association between caffeine intake and UI for Japanese adults using validated instruments. The UI prevalence estimates were comparable with previous reports for the Japanese population [16-18]. The observed slight increases in UI risk at the highest level of caffeine intake may be partially explained by the diuretic effect of beverages such as coffee and tea. Research has shown that caffeine intake can lead to a rise in detrusor pressure upon bladder filling [19]. This detrusor instability may produce a diuretic effect especially when the amount of caffeine ingested exceeds 300 mg [20]. A recent cohort study in the USA reported high caffeine intake of 450 mg or more per day significantly increased the risk of female urge incontinence [6]. Another cross-sectional study found women who experienced detrusor instability had mean caffeine intake of 484 mg/d, whereas those without at 194 mg/d [7]. Therefore, the lack of significant association in our study could be attributed to the low caffeine intake by the Japanese adults, as the mean caffeine intake was only 107 mg/d for the male and 100 mg/d for the female participants.

Reducing caffeine intake can improve urinary symptoms [21]. The Japanese Food Safety Commission has recommended an upper limit at 400 mg/d for healthy adults [22]. As such, subjects with developing symptoms may restrict their caffeine intake to reduce leaks. To avoid reverse causation, the reference period for dietary exposure was set at five years before interview. Indeed, similar levels of caffeine and total fluid intake were observed between subjects with and without UI, and none of the participants reported any change in dietary and drinking habits within the past five years.

Several limitations should be taken into consideration. The retrospective cross-sectional study design posed a major limitation so that any cause-effect relationship could not be established. Classification of UI status was based on self report via the ICIQ-SF rather than objective measures of urine loss, and seasonal alterations were not accounted for [23]. Nevertheless, it is now recognized that the use of psychometrically robust self completion questionnaires is a valid approach for assessing UI. The ICIQ-SF has good measurement properties and encompasses all aspects of incontinence [9,10]. Although information bias on the potential association was unlikely and recall error could not be eliminated, face-to-face interviews were conducted to help the recall of beverage consumption and to avoid misinterpretation of the questions. Moreover, the first author conducted all data collection thus eliminating the possibility of inter-interviewer bias. But selection bias still existed because our convenience sample comprised voluntary participants from the community. Residual confounding was another issue, even though the inclusion of more confounding factors would further bias the observed association towards the null hypothesis. The small number of incontinent cases, especially for men, might have compromised the study power and limited further detailed analysis. Therefore, the results could not be generalized to the population of Japanese adults.

In conclusion, the present study suggested little association between UI and caffeine intake in middle-aged and older Japanese adults. However, the evidence should be regarded as preliminary and further replications in other countries are needed. Population-based prospective cohort studies and experimental research are recommended to confirm the role of caffeine in the prevention of UI.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the material presented in this paper.

This article is available at http://jpmph.org/.

References

- 1.Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Diokno AC, Herzog AC, Hjälmaás K, Lapitan MC. Epidemiology and natural history of urinary incontinence. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: 2nd International Consultation on Incontinence; 2001 July 1-3; Paris, France. 2nd ed. Plymouth: Health Publication Ltd.; 2002. pp. 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallosso HM, Matthews RJ, McGrother CW, Donaldson MM, Shaw C Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Group. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with the onset of overactive bladder: a longitudinal study in men. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(7):885–891. doi: 10.1079/phn2004627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallosso HM, McGrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MM Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Group. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. BJU Int. 2003;92(1):69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koskimaki J, Hakama M, Huhtala H, Tammela TL. Association of dietary elements and lower urinary tract symptoms. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2000;34(1):46–50. doi: 10.1080/003655900750016887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallosso H, Matthews R, McGrother C, Donaldson M. Diet as a risk factor for the development of stress urinary incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(6):920–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jura YH, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Caffeine intake, and the risk of stress, urgency and mixed urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2011;185(5):1775–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(1):85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomlinson BU, Dougherty MC, Pendergast JF, Boyington AR, Coffman MA, Pickens SM. Dietary caffeine, fluid intake and urinary incontinence in older rural women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10(1):22–28. doi: 10.1007/pl00004009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(4):322–330. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karantanis E, Fynes M, Moore KH, Stanton SL. Comparison of the ICIQ-SF and 24-hour pad test with other measures for evaluating the severity of urodynamic stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(2):111–116. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murase N, Katsumura T, Ueda C, Inoue S, Teruichi S. Reliability and validity for international physical activity questionnaire in Japanese version. J Health Welf Stat. 2002;49(11):1–9. (Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishihara J, Sobue T, Yamamoto S, Sasaki S, Tsugane S JPHC Study Group. Demographics, lifestyles, health characteristics, and dietary intake among dietary supplement users in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(4):546–553. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihara J, Sobue T, Yamamoto S, Yoshimi I, Sasaki S, Kobayashi M, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC Study Cohort II: study design, participant profile and results in comparison with Cohort I. J Epidemiol. 2003;13(1 Suppl):S134–S147. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1sup_134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standard tables of food composition in Japan. 5th revised and enlarged edition, 2005. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technology-Japan. [cited 2009 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/gijyutu/gijyutu3/toushin/05031802.htm (Japanese)

- 16.Honjo H, Nakao M, Sugimoto Y, Tomita K, Kitakoji H, Miki T. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and seeking acupuncture treatment in men and women aged 40 years or older: a community-based epidemiological study in Japan. JAM. 2005;1:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto M, Inoue K. Predictors of institutionalization in elderly people living at home: the impact of incontinence and commode use in rural Japan. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2007;22(4):421–432. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homma Y, Yamaguchi O, Hayashi K Neurogenic Bladder Society Committee. Epidemiologic survey of lower urinary tract symptoms in Japan. Urology. 2006;68(3):560–564. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol. 1990;66(6):613–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1990.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maughan RJ, Griffin J. Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2003;16(6):411–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2003.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryant CM, Dowell CJ, Fairbrother G. Caffeine reduction education to improve urinary symptoms. Br J Nurs. 2002;11(8):560–565. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2002.11.8.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caffeine content in foods. Food Safety Commission. [cited 2011 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.fsc.go.jp/sonota/factsheets/caffeine.pdf (Japanese)

- 23.Yoshimura K, Kamoto T, Tsukamoto T, Oshiro K, Kinukawa N, Ogawa O. Seasonal alterations in nocturia and other storage symptoms in three Japanese communities. Urology. 2007;69(5):864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]