Abstract

Triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone, 3-AP) is currently the most promising chemotherapeutic compound among the class of α-N-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones. Here we report further insights into the mechanism(s) of anticancer drug activity and inhibition of mouse ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) by Triapine. In addition to the metal-free ligand, its iron(III), gallium(III), zinc(II) and copper (II) complexes were studied, aiming to correlate their cytotoxic activities with their effects on the diferric/tyrosyl radical center of the RNR enzyme in vitro. In this study we propose for the first time a potential specific binding pocket for Triapine on the surface of the mouse R2 RNR protein. In our mechanistic model, interaction with Triapine results in the labilization of the diferric center in the R2 protein. Subsequently the Triapine molecules act as iron chelators. In the absence of external reductants, and in presence of the mouse R2 RNR protein, catalytic amounts of the iron(III)–Triapine are reduced to the iron(II)–Triapine complex. In the presence of an external reductant (dithiothreitol), stoichiometric amounts of the potently reactive iron (II)–Triapine complex are formed. Formation of the iron(II)–Triapine complex, as the essential part of the reaction outcome, promotes further reactions with molecular oxygen, which give rise to reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thereby damage the RNR enzyme. Triapine affects the diferric center of the mouse R2 protein and, unlike hydroxyurea, is not a potent reductant, not likely to act directly on the tyrosyl radical.

Keywords: Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), Triapine, Tyrosyl radical, Metal complex, Cytotoxicity, EPR

1. Introduction

The enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) catalyzes the reduction of all four ribonucleotides to their corresponding deoxyribonucleotides, and thereby provides the precursors needed for both synthesis and repair of DNA [1]. Eukaryotic RNRs belong to class Ia RNR. They are oxygen-dependent tetrameric enzymes, composed of two subunits, R1 (α2 homodimer) and R2 (β2 homodimer). The active site is located in each α2 polypeptide in the large R1 subunit. Each β2 polypeptide in the smaller subunit R2 contains a dinuclear prosthetic group composed of two iron ions and a free stable tyrosyl radical essential for enzymatic activity.

α-(N)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones are a class of highly potent inhibitors of RNR activity [2-5]. These compounds are excellent chelators of metal ions (e.g. iron, copper, zinc) [6,7]. Currently, the most promising therapeutic compound among the thiosemicarbazones is Triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone, 3-AP). It is by a factor of 1000 more potent inhibitor of R2 RNR activity, as compared to hydroxyurea (HU), a clinically used RNR inhibitor [8]. Triapine has entered several phase II clinical trials as a chemotherapeutic agent [9-11]. The cytotoxic activity of Triapine is suggested to involve the chelation of iron and subsequent formation of the redox active iron(II)-Triapine complex [4,12,13]. The latter is able to activate molecular oxygen, resulting in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which cause damage to the cells [12].

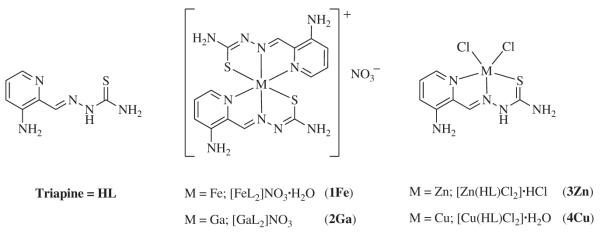

Recently, the antitumor potencies of iron(III), gallium(III) [14] and zinc(II) [15] complexes of Triapine were studied in two human cancer cell lines (41M and SK-BR-3). It was shown that the cytotoxic activity in the case of gallium(III) and zinc(II) is similar to that of the metal-free Triapine, whereas the activity of the iron(III) complex is reduced. In order to explain these observations, we have investigated the effect of Triapine and its complexes with Zn(II), Ga(III) and Fe(III), on the destruction of the tyrosyl radical in mouse R2 RNR protein by EPR spectroscopy, and on the metal chelation by UV/visible (UV/Vis) absorption spectroscopy. In addition, we have also studied the effect of the copper(II)-Triapine mono-ligand complex on the tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 protein, since copper is (along with iron and zinc) essential for growth and proliferation of vital cells. The chemical structures of the complexes investigated in this study are shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures of Triapine and the metal complexes investigated in this study.

Despite many studies on thiosemicarbazones, several questions still remain open about the mechanisms responsible for their antitumor and cytotoxic activities. The aim of the present work is to give further insights into the mechanism(s) of inhibition of RNR by Triapine and its metal complexes under different conditions.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Compounds

Triapine and its iron(III), gallium(III) and zinc(II) complexes were prepared according to previously published procedures [14,15]. The synthesis of 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazonato-N,N,S-dichloridocopper(II) monohydrate, [Cu(HL)Cl2]·H2O 4(Cu) was performed as follows: Triapine (HL) (50 mg, 0.26 mmol) dissolved in hot methanol (12 ml) was slowly added to a mixture of copper(II) chloride dihydrate (44 mg, 0.26 mmol) and conc. HCl (43 μl) in methanol (5 ml) at room temperature. Subsequently, the mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The green precipitate was filtered off, washed with methanol, diethyl ether and dried in vacuo. Yield: 59 mg (66%). Anal. Calcd for C7H9Cl2CuN5S·H2O (Mr=347.71 g/mol): C, 24.18; H, 3.19; N, 20.14; S, 9.22. Found: C,24.40; H, 3.15; N, 19.89; S, 9.29.

2.2. Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammograms were measured in a three-electrode cell using a 2.0 mm-diameter glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum auxiliary electrode, and an Ag|Ag+ reference electrode containing0.10 M AgNO3 in CH3CN. Measurements were performed at room temperature using an EG & G PARC 273A potentiostat/galvanostat. Deaeration of solutions was accomplished by passing a stream of argon through the solution for 5 min prior to the measurement and then maintaining a blanket atmosphere of argon over the solution during the measurement. The potentials were measured in 0.20 M [n-Bu4N][BF4]/DMF at ~0.002 M concentration of the metal complexes at room temperature, using [Fe(η5–C5H5)2] (E½=+0.72 V vs. NHE) [16] as internal standard, and are quoted relative to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE).

2.3. Cell lines and culture conditions

Human 41M (ovarian carcinoma) cells were kindly provided by Lloyd R. Kelland (CRC Centre for Cancer Therapeutics, Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton, UK) and Evelyn Dittrich (Department of Medicine I, Medical University of Vienna, Austria), respectively. Cells were grown in 75 cm2 culture flasks (Iwaki/Asahi Technoglass, Gyouda, Japan) as adherent monolayer cultures in Minimal Essential Medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4 mM l-glutamine and 1% non-essential amino acids (100×) (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were maintained at 310 K in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.4. Cytotoxicity tests in cancer cell lines

Antiproliferative effects of 4(Cu) were determined by means of a colorimetric microculture 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay and evaluation is based on means from three independent experiments, each comprising at least three microcultures per concentration level. Experimental details were previously reported [14].

2.5. EPR spectroscopy

The kinetics of tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by Triapine (HL) and its complexes with Fe(III), Ga(III), Zn(II) and Cu(II), was monitored by EPR spectroscopy. Mouse R2 RNR protein was expressed in Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS bacteria, essentially as described previously [17]. The R2 protein was reconstituted with an anaerobic solution of (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 at a ratio of 10 iron(II) ions per R2 monomer (polypeptide chain). Excess iron was removed by gel filtration. The R2 protein contained 2 iron ions and 0.38 tyrosyl radicals per polypeptide. EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ESP300 X-band (9.5 GHz) spectrometer with an Oxford Instruments ESR9 helium cryostat at 40 K, 3.2 mW microwave power and 5 G modulation amplitude. The concentration of the tyrosyl radical was determined by double integration of EPR spectra recorded at non-saturating microwave power levels, and compared with a standard solution of 1 mM CuSO4 in 50 mM EDTA. The calculated radical concentration was normalized and expressed in percent of the untreated sample.

The samples used for kinetic monitoring of the relative concentration of the tyrosyl radical in mouse R2 RNR protein were incubated for indicated times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The same sample was used for repeated incubations at room temperature and was refrozen before each EPR measurement. The corresponding R2 sample without drug was treated as a control and its radical concentration was subtracted at each time point (control radical concentration decreased by not more than 10% in 30 min, Supplementary Data). The experiments were repeated 3 (or 5) times starting with freshly prepared protein R2 solutions, which gave an estimate of the uncertainty of each measurement of about 5–10%.

2.6. UV/Vis spectrophotometry

Optical absorption spectra were recorded at room temperature using a V-560 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Jasco Essex, UK). All spectra were baseline corrected.

2.7. Sample preparation for EPR and UV/Vis measurements

Samples contained 30 μM mouse R2 RNR protein (concentration given as polypeptide) dissolved in tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) buffer, pH 7.60 and 30 (or 6) μM compound HL, 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) or 4(Cu) in 1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O. Some samples contained 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Control samples contained 30 μM mouse R2 RNR protein dissolved in Tris buffer, pH 7.60 (with and without DTT). For EPR measurements, the samples were incubated at 295 K for selected times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. For UV/Vis spectroscopy the samples were incubated for 15 (or 5) min at 295 K before spectra were recorded.

2.8. Molecular docking methodology

Computer docking was performed using Autodock 4.0 [18]. The three-dimensional structure of mouse R2 RNR protein was available from the Protein data bank (PDB ID: 1W68). Polar hydrogens were added to the protein using DS ViewerPro 5.0 from Accelrys (www.accelrys.com). The Mol2 structure of the ligand was constructed from http://rcmd-server.frm.uniroma1.it/rcmd-portal/. AutoDockTools was implemented to check Gasteiger charges and set maximum number of active torsions in the ligand. The two iron ions were included in the radical site. The empirical free energy function and Lamarckian genetic algorithm were applied for Autodock simulation [19]. The grid box was created involving the whole protein structure (x, y, z directions) with 0.375 Å spacing. The running number was 100, and 2,500,000 energy evaluations for each run were applied. Other parameters were selected for docking as follows: an initial population of 150 randomly placed individuals, a maximum number of 27,000 generations, a mutation rate of 0.02 and a crossover rate of 0.80. The docked compounds were clustered into same group with less than 2.0 Å in positional root mean-square deviation. Based on the cluster distribution and binding energy, we selected the best docking conformation for analysis [20].

2.9. Quantum chemical calculations

All calculations were performed using the B3LYP hybrid density functional [21] as implemented in the Gaussian03 program package [22]. Geometries were optimized employing the 6–31G(d,p) basis set for all atoms except Fe, for which the Stuttgart-Dresden pseudopotential (SDD) was used. In order to obtain more accurate energies, the geometry optimizations were followed by single-point calculations employing the larger 6–311+G(2d,2p) basis set for all atoms except for Fe, for which the SDD was used again. All reported energies include the zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections obtained from frequency calculations at the same level of theory as the geometry optimization. Solvation effects were taken into account using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) [22] with molecular cavities derived with the United Atoms Kohn-Sham (UAKS) procedure. The dielectric constant for water (ε=78.4) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Complex stability

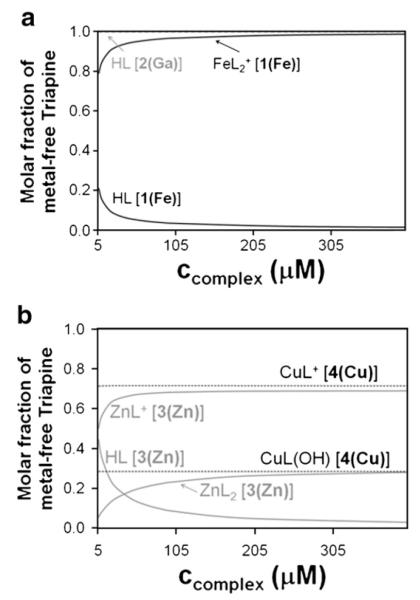

The prepared complexes of Triapine [FeL2]NO3·H2O and [GaL2]NO3 with metal-to-ligand ratio of 1:2 and the mono-ligand complexes [Zn(HL)Cl2]·HCl and [Cu(HL)Cl2]·H2O, were used for the cytotoxicity tests and tyrosyl radical destruction assays. Since all these studies were performed in aqueous solutions with 1% (w/w) DMSO, the actual forms of the dissolved complexes are crucial for understanding their biological effects. The thermodynamic equilibrium state is determined by the stability constants and the speciation is strongly dependent on the concentration of the metal complexes, the solvent, as well as the pH. Comparison of the stabilities of the Triapine complexes shows the following general order: Zn(II)<Cu(II)<Ga(III)<Fe(III), although strong tendency for hydrolysis was observed, especially in the case of Ga(III), which increases in diluted solutions and under basic conditions [23,24]. In order to predict the most plausible forms of the metal complexes at physiological pH, concentration distribution curves were calculated (Fig. 1) at different metal complex concentrations. It can be seen that all complexes tend to hydrolyze in the relevant concentration range (<50 μM), resulting in the release of the metal-free ligand (HL). 1(Fe) remains almost intact due to its high stability, but 2(Ga) is completely dissociated upon dissolution forming different gallium(III) hydroxides. In the solution of 3(Zn), [ZnL]+ is the major species with small amounts of [ZnL2] and HL (and Zn2+). In the case of the mono-ligand complex 4(Cu), formation of complexes with 1:1 stoichiometry ([CuL]+, [CuL(OH)]) is calculated, because the formation of Jahn–Teller distorted octahedral bis-ligand complexes is less favored. It should be noted, however, that calculations are based on the stability constants determined in 30% (w/w) DMSO/H2O [23,24].

Fig. 1.

Concentration distribution curves of (a) 1(Fe) and 2(Ga) (the gallium complex is completely dissociated in the whole concentration range) and (b) 3(Zn) and 4(Cu) in relation to the concentration of complex at pH 7.60. Calculations are based on data reported in [23,24].

3.2. Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxic potency of Triapine (HL) and its metal complexes was measured in the human tumor cell line 41M (ovarian carcinoma) by means of the colorimetric MTT assay (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of Triapine (HL) and its metal complexes in 41 M cells.

The metal-free Triapine ligand and its gallium(III) and zinc(II) complexes show very similar cytotoxicity, mainly due to partial, or complete, dissociation of the complexes upon dissolution in accordance with the stability data [23,24]. In contrast, coordination of Triapine to copper(II) and iron(III) results in decreased cytotoxic potency by a factor of ~3 and ~6, respectively.

3.3. Cyclic voltammetry

Zinc(II) and gallium(III) complexes of Triapine, are electrochemically silent in the biologically relevant redox potential window (−0.4 V up to +0.8 V vs. NHE [25]). In contrast, the corresponding iron(III) and copper(II) complexes exhibit redox activity. The iron(III) complex displays a reversible redox couple [Fe(III)L2]+/[Fe(II)L2] at E1/2=+0.01 V vs. NHE in DMF solution (Ea–Ec=68 mV at 200 mV/s scan rate; ia/ic=1), while in contrast the copper(II) complex of Triapine shows an irreversible reduction at Ep=+0.07 V vs. NHE at 200 mV scan rate.

3.4. Spectroscopic studies of complexes

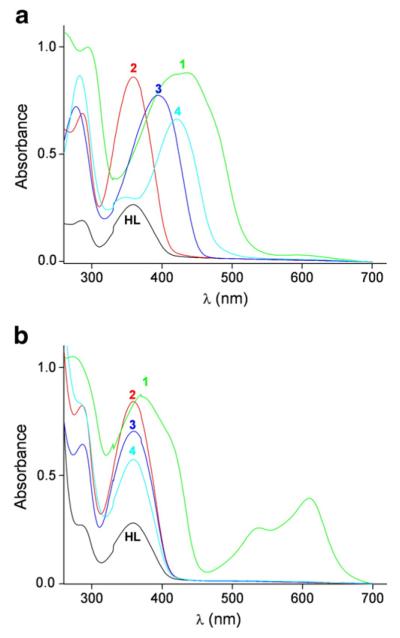

UV/Vis spectra of Triapine (HL) and its metal complexes 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu) at pH 7.60, are shown in Fig. 2a. HL and 2(Ga) show very similar UV/Vis spectra with two absorption peaks at 286 and 359 nm (Table 2). These spectra remain unchanged upon incubation with DTT (Fig. 2b). Unlike the spectrum of the other redox-inert metal complex, 3(Zn) is changed (Fig. 2b), presumably due to replacement of the Triapine ligand by DTT [26]. Compounds 1(Fe) and 4(Cu) undergo reduction after incubation with DTT, as seen from the change of the absorption maxima in Fig. 2. Compound 1(Fe) is reduced completely to [Fe(II)L2], which is clearly shown by the appearance of the characteristic charge transfer bands at 534 and 605 nm, as reported previously for the bis-Triapine complex of iron(II) [12,23]. The spectrum of the reduced form of 4(Cu) is similar to that of the metal-free ligand HL, indicating the dissociation of the metal complex under these conditions.

Fig. 2.

UV/Vis absorption spectra of HL and its metal complexes 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), under a) non-reducing, and b) reducing conditions. Samples contained 25 μM HL or 50 μM complex in 1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O, Tris buffer, pH 7.60, at 295 K and 2 mM DTT (only b).

Table 2.

Absorption maxima of Triapine (HL) and its metal complexes at pH 7.60 (in 1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O).

| Compound | HL | HL+DTT | 1(Fe) | 1+DTT | 2(Ga) | 2+DTT | 3(Zn) | 3+DTT | 4(Cu) | 4+DTT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax (nm) | 286 | 286 | 294 | 275 | 286 | 286 | 277 | 286 | 282 | 286 |

| 359 | 359 | 430 | 369 534, 605 |

359 | 359 | 394 | 359 | 421 | 359 |

Of the five compounds investigated here, only 1(Fe) and 4(Cu) are EPR active, due to the presence of paramagnetic d5 (Fe(III)) and d9 (Cu(II)) metal ions. EPR spectra obtained at 30 K are shown in Supplementary Data Fig. S3.

3.5. Mouse RNR inhibition in vitro

3.5.1. Non-reducing conditions

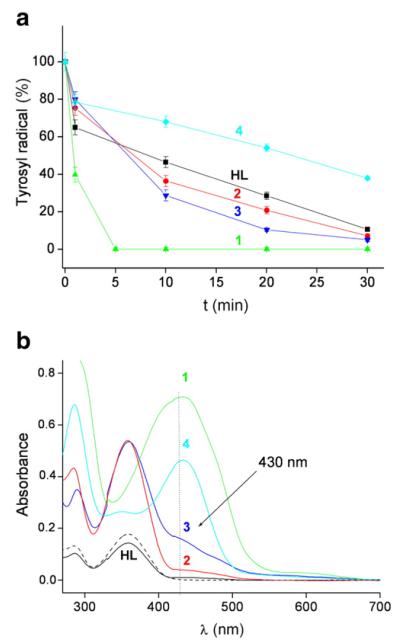

The time-dependent tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by compounds HL, 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu) was monitored by EPR spectroscopy in the absence or presence of the reducing agent DTT. The results (Figs. 3 and 4) show that the studied compounds are very efficient in tyrosyl radical destruction, particularly in the presence of DTT.

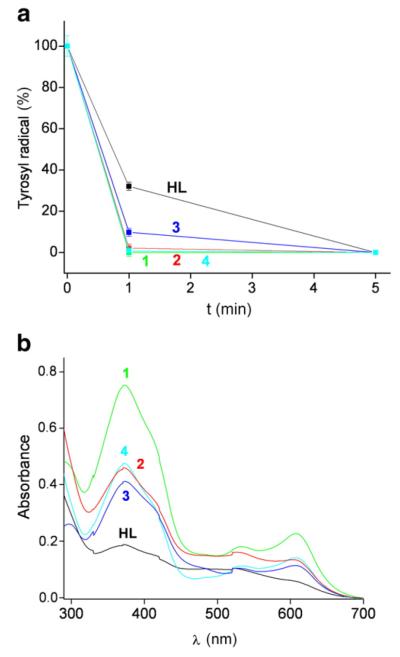

Fig. 3.

a) Tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by HL and its metal complexes, 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), in absence of DTT. Samples containing 30 μM mouse R2 protein and 30 μM compound (1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60, were incubated for indicated times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The natural decay of tyrosyl radical in the R2 protein was subtracted for each point (see Supplementary Data). b) UV/Vis spectra of the same samples as in (a) taken after 15 min reaction time at 295 K. The spectrum of 30 μM HL without R2 RNR protein (– – –) is shown for comparison.

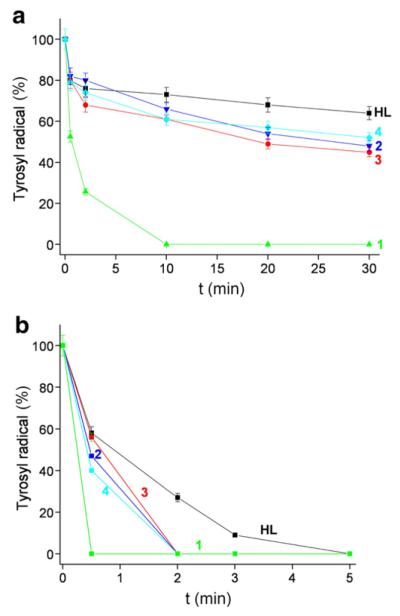

Fig. 4.

a) Tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by HL and its metal complexes, 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), in the presence of DTT. Samples containing 30 μM mouse R2 protein, 2 mM DTT, and 30 μM compound (1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60, were incubated for indicated times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The decay of the tyrosyl radical in the R2 protein in the presence of 2 mM DTT was subtracted for each point (see Supplementary Data). b) UV/Vis spectra of the same samples as in (a) taken after 5 min reaction time at 295 K.

Fig. 3a shows tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 protein by the five compounds under non-reducing conditions (in the absence of DTT). The protein (30 μM) was incubated with an equimolar amount of Triapine or its metal complexes [1% (w/w) (DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60]. Fig. 3b shows the UV/Vis spectra of the formed product(s) after 15 min reaction. We observe that all compounds show an increased absorption shoulder at ~430 nm (arrow in Fig. 3b). This shoulder can be attributed to the formation of [Fe(III)L ]+ 2 complex, indicating some degree of chelation of iron(III) from the R2 protein. Although mouse R2 protein, upon storage at room temperature, spontaneously releases iron(III) to some extent [27], there simultaneously may be a more substantial release of iron(III) in the presence of HL or its complexes, which will be further addressed in the Discussion section. As expected, the amount of compound 1(Fe) is unchanged after reaction with the protein, since there are no free Triapine molecules to chelate Fe from the protein. The concentrations of [Fe(III)L ]+ 2 formed in the reaction of the other metal complexes with mouse R2 protein could not be determined for 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), as their spectra are significantly overlapping (at 430 nm) with those of the unaltered complexes (Fig. 2a). For HL and 2(Ga), the amount of the formed [Fe(III)L ]+ 2 complex, estimated from Fig. 3b, was 1 and 2.5 μM, respectively.

3.5.2. Reducing conditions

In presence of an external reductant (here DTT), the tyrosyl radical is destroyed very efficiently (100% after 5 min) by all five compounds. Incubation of mouse R2 protein with DTT alone does not lead to tyrosyl radical destruction, but rather results in a slight increase in tyrosyl radical content (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data) [28]. Fig. 4a shows tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 protein by the compounds in the presence of DTT, when the R2 protein was incubated with an equimolar amount of Triapine or its metal complexes. Fig. 4b shows the UV/Vis spectra of the formed products after 5 min reaction of 30 μM mouse R2 protein and an equimolar amount of the investigated compounds (1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60, and 2 mM DTT. It can be seen that these reactions result in the formation of the [Fe(II)L2] complex. To quantify the amount of the formed [Fe(II)L2] compound, UV/Vis absorbance of the charge transfer band at 605 nm was measured. This absorption was compared to that of [Fe(II)L2] at known concentrations. We found that in the presence of DTT the reaction of 30 μM of 1(Fe) with 30 μM mR2 resulted in quantitative reduction of [Fe(III)L2]+ to [Fe(II)L2], whereas other compounds formed less than 30 μM [Fe(II)L2] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Concentration of [Fe(II)L2] formed in the reaction of 30 μM mR2 with 30 μM of HL and 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn), 4(Cu) in the presence of 2 mM DTT.

| Compound | c[Fe(II)L2] (μM) |

|---|---|

| HL (Triapine) | 7.9±0.5 |

| 1(Fe) | 30.0±1.5 |

| 2(Ga) | 17.6±0.8 |

| 3(Zn) | 15.2±0.7 |

| 4(Cu) | 18.7±0.9 |

3.5.3. Lower concentration of the metal complexes

The destruction of the tyrosyl radical in protein R2 was further investigated using lower concentration of the compounds (6 μM drug and 30 μM R2 RNR protein) (Fig. 5). These results show that even substoichiometric concentrations of the compounds HL, 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), are able to destroy about 50% of tyrosyl radical after 30 min reaction, and that compound 1(Fe) is able to destroy 100% tyrosyl radical after 10 min reaction in the absence of DTT (Fig. 5a). In the presence of DTT, all compounds are able to destroy the radical within a few minutes (Fig. 5b). Very low concentrations of the complexes(0.125 μM, 250 times less than the concentration of the protein) showed essentially no effect on the tyrosyl radical (data not shown), except for compound 1(Fe) (Fig. 6b) which in the presence of DTT could destroy the radical completely in 2 min.

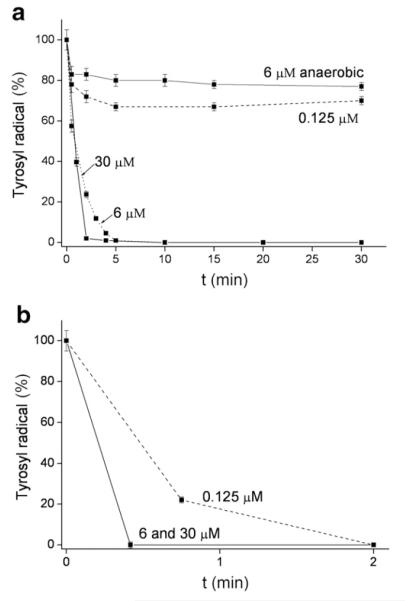

Fig. 5.

Tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by HL and its metal complexes, 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu) in a) absence and b) presence of DTT. Samples containing 30 μM mouse R2 protein and 6 μM compound (1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60, and 2 mM DTT (b only) were incubated for indicated times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The natural decay of tyrosyl radical in mouse R2 protein without DTT (a) or in the presence of DTT (b) was subtracted for each point.

Fig. 6.

Tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 RNR protein by compound 1(Fe) ina) absence and b) presence of DTT. Samples containing 30 μM mouse R2 protein and 30, 6 or 0.125 μM compound 1(Fe) (1% (w/w) DMSO/H2O) in Tris buffer, pH 7.60, and 2 mM DTT (b only) were incubated for indicated times and quickly frozen in cold isopentane. The top curve in a) was obtained in anaerobic conditions (oxygen was removed from the protein by gentle evacuation and refilling with argon over a period of 20 min). The natural decay of tyrosyl radical in mouse R2 protein in the absence (a) or in the presence of DTT (b) was subtracted for each point.

The requirement for oxygen for complete destruction of tyrosyl radical by 1(Fe) is shown in Fig. 6a (top curve). It is observed that 1(Fe) at concentration of 6 μM under aerobic conditions destroys 100% tyrosyl radical after 5 min, whereas the same concentration of the compound, under anaerobic conditions, destroys only about 20% radical after 30 min. This indicates that ROS formed in the reaction of [Fe(II)L2] and O2 [12], are needed for complete RNR inactivation.

3.6. Molecular docking

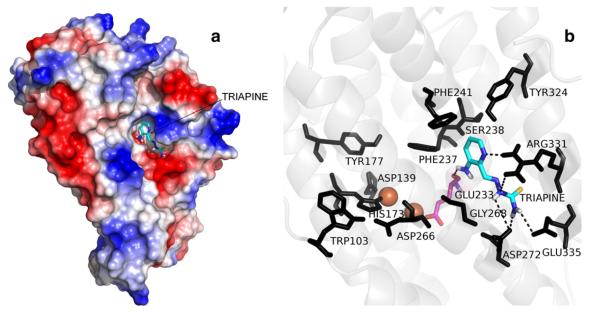

To investigate a possible binding site of Triapine on the mouse R2 RNR protein, molecular docking was performed on the whole protein. The most favorable binding conformations were extracted from the cluster with the lowest calculated energies and the highest average number of conformers. The calculated binding site for Triapine (Fig. 7) is located on the interface of positive and negative charged surfaces, and is composed of two binding pockets. A number of conformers appear in the same position with the same orientation (Supplementary Data), which provides a reasonable docking model. Within this model, the pyridine ring of Triapine is located in the pocket formed by four amino acids, Phe237, Phe241, Ser238 and Tyr324. Furthermore, the interaction of Triapine with mouse R2 RNR protein involves hydrogen bonding with four amino acids, Glu233, Glu335, Asp272 and Arg331. Glu233 in mouse R2 is a monodentate terminal ligand to one of the ferric ions.

Fig. 7.

The calculated binding pocket for Triapine on the surface of the mouse R2 RNR protein. a) Structure of mouse R2 RNR protein with bound Triapine. The red and blue areas represent positive and negative charge, respectively, in the surface potential map. Triapine is shown in stick representation (cyan). b) Binding site showing hydrogen bonding between Triapine (cyan) and Glu233, Glu335, Asp272 and Arg331; and interactions with Phe237, Phe241, Ser238 and Tyr324. All residues are shown in black, only Glu233 in magenta, for clarity. The diferric center is represented as two orange spheres.

3.7. Quantum chemical calculations

To shed more light on the energies involved in the process of tyrosyl radical reduction, we have used density functional theory (DFT) to calculate the bond dissociation energies X–H→X•+H• (BDEs; X==N, O) of hydroxyurea, Triapine and its 1:2 iron(III) and iron(II) complexes and compared these to the O–H BDE of tyrosine (here modeled as a p-methylphenol). The results are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Calculated bond dissociation energies (kcal/mol) in gas phase and aqueous solution (ε=78.4).

| BDE (kcal/mol) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | Gas phase | In solution |

| p-methylphenol | 80.4 | 80.0 |

| Hydroxyureaa | 68.7 | 71.5 |

| Triapine (HL)a | 82.0 | 85.9 |

| [Fe(III)L2]+a | 88.8 | 88.9 |

| [Fe(II)L2]a | 83.4 | 85.1 |

For these compounds, several radical sites are possible. Only the lowest energy ones are reported here. For details on the other possibilities, see Supplementary Data.

The calculations show that all BDEs for Triapine and its metal complexes are within a relatively small range and close to the BDE for the model tyrosyl radical, suggesting that it could in principle be possible to transfer electrons between the different partners. The BDE in aqueous solution of Triapine alone, 85.9 kcal/mol, is changed to 85.1 kcal/mol and 88.9 kcal/mol for complexes with iron(II) and iron(III), respectively (Table 4). Comparison with the calculation for hydroxyurea (HU) shows that HU has a significantly lower BDE, implying that it is a highly efficient direct reductant of the tyrosyl radical. Indeed, HU is known to selectively reduce the tyrosyl radical, leaving the iron center intact in E. coli R2 protein [29]. In contrast, HU can reduce both the tyrosyl radical and the iron center in mammalian R2 protein [30,31]. For Triapine and its metal complexes, although direct reduction of the tyrosyl radical cannot be ruled out by the present calculations, we suggest that their potent ability to inhibit RNR should be linked to other mechanisms, involving chelation of iron. The direct tyrosyl radical reduction, although possibly present to some extent, will not be further discussed here. It should also be mentioned that for each of the investigated compounds, all possible radicals were considered, and for the metal complexes, all possible spin states were calculated. In Table 4 only the lowest energy ones are reported. In the case of the Triapine complex with iron(II), the calculations indicate that it is equally feasible to remove the electron from either the Triapine ligand or from iron(II), while for the Triapine complex with iron(III) the electron is taken from the ligand. The complete list of results, along with the optimized geometries can be found in Supplementary Data.

4. Discussion

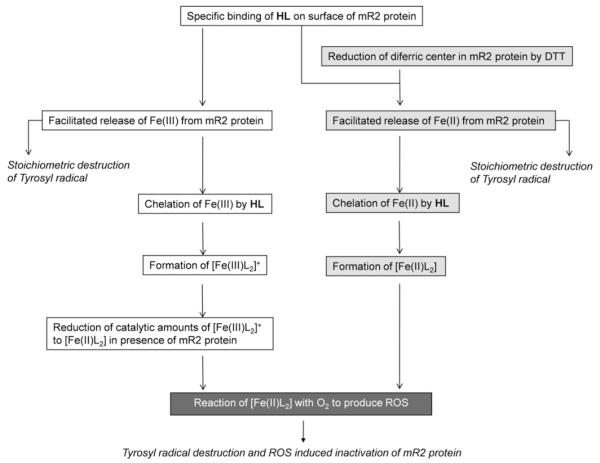

This study shows that Triapine (HL) and its metal complexes 1(Fe), 2(Ga), 3(Zn) and 4(Cu), inhibit mouse R2 RNR protein in vitro, in both absence and presence of external reductants. Under non-reducing conditions, HL and complexes 2(Ga) and 3(Zn), show similar kinetics of the tyrosyl radical destruction. Their similar inhibition kinetics are due to the fact that compounds 2(Ga) and 3(Zn) can easily dissociate in aqueous solution at pH 7.60, to give free metal ions and Triapine (in the case of 3(Zn) this occurs only at concentrations <150 μM, see Fig. 1). Below we will summarize the likely steps involved in the RNR inhibition mechanism by HL and its metal complexes (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Summary of possible mechanism steps of mouse RNR inhibition by Triapine under non-reducing and reducing conditions. Less efficient inhibition, observed in non-reducing conditions, involves binding of Triapine to mouse R2 RNR protein which leads to facillitated release of iron(III) from the protein. Subsequently, Triapine chelates iron(III) to form [Fe(III)L2]+. In the presence of mouse R2 protein the iron complex is reduced to [Fe(II)L2], which then in presence of molecular oxygen leads to ROS induced inactivation of the R2 protein. More efficient inhibition, observed under reducing conditions, involves the reduction of the diferric center in mouse R2 protein by the external reductant DTT, followed by chelation of released iron(II) by HL. The formed [Fe(II)L2] complex activates molecular oxygen and results in ROS induced inactivation of the R2 protein. Reaction steps that take place in the absence or presence of external reductant are shown in white and light gray, respectively; Reaction step that requires the presence of oxygen is shown in dark gray.

During the reaction of mouse R2 protein with equimolar amounts of HL, 2(Ga) and 3(Zn), tyrosyl radical destruction and formation of [Fe(III) L2]+ are observed (Fig. 3). The formation of [Fe(III)L2]+ indicates that iron is released from the protein as iron(III). Since mouse R2 protein tends to spontaneously release iron at room temperature [27], it is quite possible that this iron is chelated by HL molecules. The extent of spontaneously released iron from mouse R2 protein can be estimated from the amount of destroyed tyrosyl radical caused by storage of the protein at room temperature (and in the absence of HL and its metal complexes). The slow (spontaneous) decay of the radical in the control sample is shown to be not more than 10% in 30 min (Supplementary Data, Fig. S2). However, tyrosyl radical destruction caused by HL, 2(Ga) and 3(Zn) is significantly faster (approximately 90% in 30 min) (Fig. 3a).3

Since the quantum chemical calculations show that neither Triapine nor its metal complexes should be very efficient to directly reduce the tyrosyl radical, we suggest that HL promotes protein bound iron to be released as iron(III). This suggestion may be supported by the fact that a specific binding site for HL on the surface of mouse R2 protein was indicated by molecular docking (Fig. 7). In this proposed binding site, the pyridine ring of HL is located in the pocket formed by Phe237, Phe241, Ser238 and Tyr324. Furthermore HL is involved in hydrogen bonding with Glu233, Glu335, Asp272 and Arg331. Possibly hydrogen bonding between HL and Glu233, which is a monodentate terminal ligand to one of the ferric ions in mouse R2 protein, may facilitate iron(III) release from the protein. Obviously, loss of iron(III) directly leads to stoichiometric destruction of tyrosyl radical. At the same time, labilized iron(III) is chelated by HL and the [Fe(III)L2]+ complex is formed. Our results show that the [Fe(III)L2]+ complex is an efficient inhibitor of mouse R2 RNR protein (Figs. 3a and 5a). Since it has been previously shown that this complex cannot activate O2 and produce ROS in a Fenton-like reaction [12], nor is it capable of reducing the tyrosyl radical (Table 4), we suggest that its efficient enzyme inhibition is caused by at least a minor presence of the reduced form of the complex, [Fe(II)L2], since we show that only catalytic amounts are needed for complete destruction of the tyrosyl radical (Fig. 6b). The exact mechanism of reduction of [Fe(III)L2]+ to [Fe(II)L2] in the presence of mouse R2 protein in vitro, remains unexplained here. However, recent findings show that protein bound cysteines can efficiently reduce [Fe(III)L2]+ to [Fe(II)L2] [32]. We suggest that in our experiments, the reducing equivalents needed for the reduction of [Fe(III)L2]+ to [Fe(II)L2] may be provided by the mouse R2 protein itself.

Under reducing conditions (in presence of DTT), RNR inhibition by HL is much more efficient than in the absence of a reducing agent (Figs. 4a and 5b). Under these conditions, 100% tyrosyl radical is destroyed after 5 min by HL and all metal complexes investigated in this study. In these reactions we observe the formation of the reduced iron complex [Fe(II)L2] (Fig. 4b). The mechanism of inhibition by HL in the presence of an external reductant should be slightly different. In this case, beside specific binding of HL on the surface of mouse R2 protein, there is efficient reduction of the diferric center by DTT [28], which causes release of protein bound iron as iron(II). Iron(II) is much more labile than in its native diferric oxo-bridged form [31], so it is easily chelated by HL, resulting in the formation of the potently redox active [Fe(II)L2] complex. Finally, as described previously, ROS formed in the reaction of [Fe(II)L2] and O2, lead to complete enzyme inactivation.

At least two mechanisms, as shown in Scheme 2, which cause destruction of the tyrosyl radical in mouse R2 protein in vitro, are indicated here. The first mechanism involves stoichiometric loss of tyrosyl radical, which is caused by the release of protein bound iron as the result of specific binding of Triapine (and reduction of the diferric center if external reductant is present). The second mechanism is tyrosyl radical destruction due to enzyme inactivation caused by ROS. The former is observed under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, whereas the latter requires the presence of molecular oxygen (Fig. 6a).

Compound 4(Cu) shows the least efficient tyrosyl radical destruction in mouse R2 protein. Copper(II) forms a highly stable mono-ligand complex compared with the mono-ligand complexes of Triapine formed with other metal ions (log{K([CuL]+)/K([CuL2])} value is quite high) [23]. This agrees with EPR spectroscopy and cyclic voltammetry studies of bis-ligand copper(II) complexes [CuL2] of e.g. di-2-pyridylketon-4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone which show dissociation of the 1:2 complex to give significant amounts of the 1:1 metal-to-ligand complex [33]. We propose that the reason for slow tyrosyl radical destruction by 4(Cu) is its high conditional stability constant at physiological pH. Once it is added in vitro to mouse R2 RNR protein in non-reducing conditions, it dissociates more slowly than the other investigated compounds to give free Triapine ligands. This observation is supported by the fact that 4(Cu) shows similar inhibition kinetics at two different concentrations of the complex (6 and 30 μM, Figs. 3a and 5a, respectively). The results from the experiments performed under reducing conditions with external DTT present, show that even compound 4(Cu) is quite efficient, probably because the reduced form of this compound (with copper(I)) easily dissociates to give free Triapine (Fig. 2b).

RNR inhibition by HL in vivo, most probably involves all steps presented in Scheme 2 to varying degrees. The reducing environment inside a living cell [34] may be potent enough to make the pathway observed in reducing conditions in vitro the major one for the cytotoxic activity of the drugs. However, as cells have developed a variety of defense mechanisms against the harmful effects of ROS (i.e. catalase and superoxide dismutase activity), RNR inhibition is not as effective as under in vitro reducing conditions. Here, we also point out that iron chelation is a necessary step for efficient RNR inhibition in vivo, as we have shown that compound 1(Fe) shows decreased cytotoxicity compared to HL (Table 1). This complex is highly stable and remains intact at pH 7.60 [24]. Due to its high stability, dissociation is negligible, therefore, metal-free Triapine, which could sequester iron from protein R2 is not present. In the cell, the reduced 1(Fe) complex inactivates the enzyme, but obviously retains the R2 diiron cofactor intact, which under appropriate conditions, could be reactivated with molecular oxygen. This, together with lower uptake kinetics of the positively charged iron(III) complex may be a possible reason of reduced cytotoxicity compared to metal-free Triapine.

4(Cu) also shows decreased cytotoxicity compared to metal-free Triapine. In contrast, previously published studies on copper thiosemicarbazonate complexes show higher cytotoxic activities compared to the metal-free ligands, in several different cancer cell lines [35]. Their increased cytotoxicity is possibly due to the reaction with intracellular thiols, which reduce them to copper(I) complexes, which dissociate with liberation of the thiosemicarbazone ligands [36,37]. In the case of 4(Cu), the decreased cytotoxicity may be attributed to both high complex stability and its redox properties.

5. Conclusion

Triapine inhibits mouse RNR by affecting the diiron center of the R2 protein and unlike hydroxyurea, its major effect here is not to directly reduce the tyrosyl radical. in vitro inhibition of mammalian RNR by Triapine may involve specific binding of the drug to the surface of the R2 protein, resulting in facilitated labilization of the iron center in the protein. In the absence of external reductant (DTT), iron(III) is chelated by Triapine and the iron(III)-Triapine complex is formed. In the presence of reductant, the protein bound iron(III) may be reduced to iron(II) already before chelation by Triapine. Loss of iron from protein R2 leads immediately to destruction of the tyrosyl radical in the protein. Depending on the presence or absence of external reductants, variable amounts (stoichiometric or catalytic) of the potently reactive iron(II)–Triapine complex are formed. The iron(II)–Triapine complex, may react further with molecular oxygen, which gives rise to ROS and thereby damages the enzyme. These observations, which are valid for all compounds studied here to varying degrees, are in agreement with previous proposals [5,12,13] about the inhibitory role of thiosemicarbazones for RNR. However, the exact contributions and the molecular details of the various mechanisms that may be involved in RNR inhibition (direct tyrosyl radical reduction, iron chelation, attack by ROS) seem to depend strongly on the environmental conditions.

The present study shows that the choice of the metal ion that is part of a Triapine complex affects the extent of R2 RNR inhibition, as well as the cytotoxicity for cancer cells. Our results suggest likely explanations for the relatively low cytotoxicities exhibited by the stable Triapine complexes formed by iron(III) and copper(II). The iron(III) complex does not chelate the protein bound iron, and allows for the possible reactivation of the RNR enzyme. This protective role of the iron(III) complex for RNR in vivo, confirms that the mechanism of the most efficient inhibition by Triapine should involve iron chelation. The decreased cytotoxicity of the copper(II) complex, however, may be attributed to its high conditional stability at physiological pH and its redox properties. The Triapine complexes of zinc(II) and gallium(III) with lower conditional stability constants at physiological pH result in more potent cytotoxicity, similar to that of free Triapine. The new observations reveal that the choice of the metal ion can strongly modulate the mechanism of action of a given cytotoxic ligand, which suggests the future design of complexes which are selectively activated in the tumor tissue with release of cytotoxic ligands and/or metal ions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

A.P.-B. acknowledges the financial support from the Sven and Lilly Lawski Fund. C.R.K. gratefully acknowledges the Austrian Science Fond (FWF) for financial support (grant P22072). É.A.E. acknowledges the financial support of the Bolyai J. research fellowships. A.G. acknowledges the Swedish Research Council for financial support. We also thank Robert Trondl (University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria) for performing cytotoxicity assays.

Abbreviations

- 1(Fe)

[FeL2]NO3·H2O, Bis(3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazonato)-N,N,S-iron(III) nitrate monohydrate

- 2(Ga)

[GaL2]NO3, Bis(3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazonato)-N,N,S-gallium(III) nitrate

- 3(Zn)

[Zn(HL)Cl2]·HCl, (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazonato)-N,N,S-dichloridozinc(II) hydrochloride

- 4(Cu)

[Cu(HL)Cl2]·H2O, 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazonato-N,N,S-dichloridocopper(II) monohydrate

- HL

Triapine, 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone

- HU

Hydroxyurea

- BDE

Bond dissociation energy

- DFT

Density functional theory

- DMF

Dimethylformamide

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- mR2

R2 subunit of mouse ribonucleotide reductase

- RNR

Ribonucleotide reductase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SDD

Stuttgart-Dresden pseudopotential

- Tris

Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.07.003.

Footnotes

Note that in Fig. 3a, tyrosyl radical destruction in the control sample was subtracted for each time point, hence 90% reduction is caused only by the compounds and not by spontaneous release of iron from the protein.

References

- [1].Thelander L, Reichard P. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1979;48:133–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thelander L, Gräslund A. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:4063–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moore EC, Sartorelli AC. In: Inhibitors of Ribonucleoside Diphosphate Reductase Activity. Cory GJ, Cory AH, editors. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1989. pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chaston TB, Lovejoy DB, Watts RN, Richardson DR. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:402–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yu Y, Kalinowski DS, Kovacevic Z, Siafakas AR, Jansson PJ, Stefani C, Lovejoy DB, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:5271–5294. doi: 10.1021/jm900552r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sartorelli AC, Agrawal KC, Tsiftsoglou AS, Moore AC. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1977;15:117–139. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(77)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Antholine W, Knight J, Whelan H, Petering DH. Mol. Pharmacol. 1977;13:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Finch RA, Liu M-C, Cory AH, Cory JG, Sartorelli AC. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2000;39:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(98)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Knox JJ, Hotte SJ, Kollmannsberger C, Winquist E, Fisher B, Eisenhauer EA. Invest. New Drug. 2007;25:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nutting CM, van Herpen CML, Miah AB, Bhide SA, Machiels J-P, Buter J, Kelly C, de Raucourt D, Harrington KJ. Ann. Oncol. 2009;20:1275–1279. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Traynor AM, Lee JW, Bayer GK, Tate JM, Thomas SP, Mazurczak M, Graham DL, Kolesar JM, Schiller JHA. Invest. New Drug. 2010;28:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shao J, Zhou B, Di Bilio AJ, Zhu L, Wang T, Qi C, Shih J, Yen Y. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:586–592. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yu Y, Wong J, Lovejoy DB, Kalinowski DS, Richardson DR. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:6876–6883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kowol CR, Trondl R, Heffeter P, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Roller A, Galanski M, Berger W, Keppler BK. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:5032–5043. doi: 10.1021/jm900528d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kowol CR, Trondl R, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Lichtscheidl I, Keppler BK. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:704–706. doi: 10.1039/b919119b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Barette WC, Jr., Johnson HW, Jr., Sawyer DT. Anal. Chem. 1984;56:1890–1898. doi: 10.1021/ac00275a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mann GJ, Gräslund A, Ochiai E-O, Ingemarson R, Thelander L. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1939–1947. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. J. Comput, Chem. 2007;28:1145–1152. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr., Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03 Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Barone V, Cossi M. J. Phys, Chem. A. 1998;102:1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Enyedy ÉA, Nagy NC, Zsigo E, Kowol CR, Arion VB, Keppler BK, Kiss T. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010;2010:1717–1728. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Enyedy ÉA, Primik MF, Kowol CR, Arion VB, Kiss T, Keppler BK. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:5895–5905. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01835j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kirlin WG, Cai J, Thompson SA, Diaz D, Kavanagh TJ, Jones DP. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Krezel A, Lesniak W, Jezowska-Bojczuk M, Mlynarz P, Brasun J, Kozlowski H, Bal W. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;84:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nyholm S, Mann GJ, Johansson AG, Bergeron RJ, Gräslund A, Thelander L, Biol J. Chemistry. 2005;268(1993):26200–26226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gräslund A, Ehrenberg A, Thelander L. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:5711–5715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sahlin M, Gräslund A, Petersson L, Ehrenberg A, Sjöberg B-M. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2618–2625. doi: 10.1021/bi00432a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McClarty GA, Chan AK, Choy BK, Wright JA. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:7539–7547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nyholm S, Thelander L, Gräslund A. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11569–11574. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Myers JM, Antholine WE, Zielonka J, Myers CR. Toxicol. Lett. 2011;201:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jansson PJ, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5759–5769. doi: 10.1021/jm100561b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Adsule S, Barve V, Chen D, Ahmed F, Dou QP, Padhye S, Sarkar FH. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7242–7246. doi: 10.1021/jm060712l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].García-Tojal J, García-Orad A, Alvarez Díaz A, Serra JL, Urtiaga MK, Arriortua MI, Rojo T. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;84:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Minkel DT, Petering DH. Cancer Res. 1978;38:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.