Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that aging is associated with prolonged pulmonary inflammation in a murine model of thermal injury. To further investigate these observations, we examined lung congestion, markers of neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion, and lung endothelia responses in young and aged mice following burn injury. Analysis of lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid 24 hours after injury revealed that more neutrophils accumulated in the lungs of aged mice (p<0.05), but did not migrate into the alveoli. We then sought to determine if accumulation of neutrophils in the lungs of aged mice was due to differences in the peripheral neutrophil pool or local changes within the lung. Following burn injury, aged mice developed a pronounced peripheral blood neutrophilia (p<0.05) in comparison to their younger counterparts. In aged animals, there was a reduced frequency and mean fluorescent intensity of neutrophil CXCR2 expression (p<0.05). Interestingly, in uninjured aged mice, peripheral blood neutrophils demonstrated elevated chemokinesis, or hyperchemokinesis, (p<0.05), but showed a minimal chemotatic response to KC. To determine if age impacts neutrophil adhesion molecules, we assessed CD62L and CD11b expression on peripheral blood neutrophils. No age-dependent difference in the frequency or mean fluorescent intensity of CD62L or CD11b was observed post-burn trauma. Examination of pulmonary vasculature adhesion molecules which interact with neutrophil selectins and integrins revealed that intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) was elevated in aged mice at 24 hours after burn as compared to young mice (p<0.05). Overall, our data suggests that age-associated pulmonary congestion observed following burn injury may be due to differences in lung endothelial adhesion responses that are compounded by elevated numbers of hyperchemokinetic circulating neutrophils in aged mice.

Keywords: Adhesion, Aging, Chemotaxis, Neutrophils, Lung, Burn injury

While the mortality of burn patients over the age of 65 has improved over the last few decades, clinical outcomes are still very poor [1, 2]. As the proportion of elderly individuals continues to rise, this issue will translate into a greater socioeconomic burden. It is therefore important that new treatment strategies are developed to minimize the effects of age on the response to burn and other forms of traumatic injury.

Similar to other insults which lead to systemic inflammation, the development of pulmonary complications, such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome, are often the most serious threat to the burn patient and are especially detrimental to the elderly [3–5]. In contrast to most other organs in the body, the lung has two potential routes for an inflammatory insult: through the airway and through the bloodstream. Interestingly, the pathogenesis of pulmonary inflammation is dependent on where the stimulus is located. When an inflammatory source is located in the airway, a rapid neutrophil recruitment to the alveolar space is observed [6–12]. However, when the source originates elsewhere in the body and disseminates through the blood, neutrophil accumulation within the pulmonary vasculature occurs, but cells do not migrate into the alveoli; here, the neutrophils are said to be “sequestered” in alveolar capillaries [13–15] The difference between these two host responses are established by multiple factors including chemokine gradients and expression of adhesion molecules [7, 16, 17].

Regardless of the mechanism of pulmonary inflammation, neutrophil chemokines are important in neutrophil recruitment in response to local or systemic injury. In mice, the main chemokines involved in the process are macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2, or CXCL2) and KC (or CXCL1), analogues of human growth-related oncogene α and β, respectively [18, 19]. These chemokines both bind to the receptor, CXCR2, on neutrophils [20, 21]. Not only do these chemokines act to stimulate neutrophil chemotaxis towards an inflammatory stimulus, but also to induce firm adhesion to the endothelium and to mediate diapedesis [19, 21, 22]. These studies also imply that there is a sequential order of signaling required for neutrophil diapedesis involving both selectins (CD62L) and integrins (CD11/CD18) [19, 23]. Following ligation of the neutrophil chemotatic receptor CXCR2, activation of the small GTPase: Ras-related protein-1 (Rap1) and phospholipase C (PLC) promotes upregulation of neutrophil selectins and integrins [24–26]. Subsequent interaction and cross-linking of CD62L, further upregulates integrin activity and allows neutrophils to roll and loosely adhere to the vascular endothelium [27, 28]. Together, this results in clustering of CD11/CD18, as well as other adhesion molecules, and promotes firm adhesion of the neutrophils to the endothelium via intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) [17]. Neutrophils can then interact with chemokines immobilized on the apical side of endothelial cells and begin the process of diapedesis [21, 29, 30].

Previously, our laboratory was the first to show that aged mice have prolonged pulmonary inflammation after burn injury compared to young mice with a comparable insult, marked by neutrophil accumulation and increased KC levels [31]. Herein we demonstrate that following burn trauma, aged mice have an elevated number of neutrophils in both the peripheral blood and lung that is unrelated to differences in neutrophil chemotatic or adhesion markers. Moreover, our data suggest that an age-associated elevation in lung endothelial ICAM-1 may promote the observed pulmonary congestion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Young (2–6 months) and aged (18–22 months) female BALB/c mice were obtained from the National Institute of Aging colony at Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with standard laboratory rodent chow and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were performed according to the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Institutes of Health, and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Loyola University Medical Center.

Induction of Burn Injury

As previously described, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg i.p.), shaved and placed into a plastic template designed to give a 15% total body surface area, full-thickness dorsal scald injury when immersed in a boiling water bath for 8 seconds [31, 72, 73]. As a control, separate groups of young and aged mice received a sham injury, in which they were administered anesthesia and shaved, but immersed in a room temperature water bath. Immediately following injury, the mice received warm saline resuscitation and their cages were placed on heating pads until fully recovered from anesthesia. Mice were sacrificed using CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation. In addition, all mice—including those which died before the time of sacrifice—were examined for visible tumors and, if found, were removed from the study.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

To determine the cell populations in the alveolar space, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed on young and aged mice 24 hours after receiving either a burn or a sham injury [6][2]. Immediately following sacrifice, the trachea was exposed and a small incision was made just below the cricothyroid cartilage. The trachea was then cannulated using 22 gauge needles and 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline was repeatedly injected until 5 ml of fluid was recovered for each animal. BAL cells were immunostained for flow cytometry analysis, as described below.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Neutrophils

Blood was taken via cardiac puncture of the left ventricle. For chemotaxis assays, samples were diluted 1:1 in Hank’s Buffered Saline Solution (HBSS), layered on Histopaque 1083 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and centrifuged at 400 g for 30 minutes at 20°C without the brake applied. The monocyte and plasma layers were aspirated, leaving granulocytes and erythrocytes. Samples were resuspended in HBSS and 3% dextran was added to sediment the erythrocytes. After 45 minutes at room temperature, the top layer containing granulocytes was removed and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes. Any remaining erythrocytes were lysed using ACK buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Chemotaxis Assay

Neutrophils were isolated as described above. Chemotaxis assays were then performed as described by others [52, 74]. Neutrophils were centrifuged and resuspended in 40 μM of Cell Tracker Green (Invitrogen) in chemotaxis media containing HBSS, 25 mM HEPES and 1% BSA at 106 cells/ml. The cells were then incubated in the dark for 45 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. After washing, the cells were resuspended in chemotaxis media at 106 cells/ml. The bottom wells of a chemotaxis chamber (NeuroProbe, Gaithersburg, MD) were filled with various concentrations of recombinant mouse KC (R&D Systems). A separate set of wells were filled with media alone as a negative control or 10−7 M fMLP (Sigma) as a positive control. Another set of wells were filled with sample inputs to determine the fluorescence of the starting cell suspension. A filter membrane containing 8 μm pores (NeuroProbe) was then placed over the wells and cell suspensions were added to the upper side of the membrane at 106/ml. Samples were incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell suspensions were then aspirated off the top membrane and 20 μM EDTA was added to the upper side of the membrane for 15 minutes to allow any cells adhering to the membrane to detach. The membrane was then removed and the fluorescence of the bottom wells was measured in a fluorescence spectrophotometer. The percent of cells migrating was determined by comparing the fluorescence of the cells in the sample wells to that of the input wells.

Flow Cytometry

Analyses utilizing flow cytometry were performed as previously described [75, 76]. Cells were washed with HBSS and blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then stained for 30 min at 4°C using anti-mouse antibodies at saturating concentrations, washed twice and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (FACSCanto, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Anti-mouse antibodies were used at the following concentrations: 2 μg/ml of PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse Gr-1 (Invitrogen), 20 μg/ml of APC-conjugated rat anti-mouse F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) 10 μg/ml of FITC-conjugated rat-anti mouse Gr-1 (eBioscience), 12.5 μg/ml of PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CXCR2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 10 μg/ml of PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b (eBioscience). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Immunofluorescence

The lungs were removed at the time of sacrifice, inflated with 25% O.C.T. freezing medium, and embedded for frozen sectioning as previously described [31]. Tissue sections were fixed in acetone and blocked with normal goat serum. To determine neutrophil content in lungs, sections were first incubated with 1 μg/mL of rat anti-Gr-1 antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by 4 μg/ml of goat anti-rat IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Since Gr-1 can also be found on certain macrophage populations [3, 4], the sections were dual-stained with 0.2 μg/mL of biotinylated anti-MOMA-2 antibody (BMA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), a pan-macrophage marker, and detected with 2 μg/ml of Cy3 Streptavidin (Invitrogen). Using fluorescent microscopy, the total number of neutrophils (designated as Gr-1+ MOMA-2− cells) were counted across 10 high power fields for each animal [5]. Data are expressed as mean number of neutrophils counted in ten 400x fields ± SEM. The total tissue area across which cells were counted was quantified and determined to be consistent between animals in all treatment groups (data not shown).

To determine the expression of endothelial ICAM-1 in the lungs after burn or sham injury, sections were incubated with 0.25 μg/ml of Armenian hamster anti-mouse ICAM-1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), followed by 3 μg/ml of goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Since ICAM-1 is also expressed on lung epithelium, sections were dual stained with 0.16 μg/ml of rat anti-mouse platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, BD Biosciences), and subsequently by 4 μg/ml of goat anti-rat IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Expression of ICAM-1 on lung endothelium was determined by quantifying the total area of ICAM-1 and PECAM-1 colocalization across ten 400x fields per animal. Colocalization is expressed as the area of ICAM-1+PECAM-1+ (μm2) staining. All fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) and are expressed as mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc was used to determine statistical differences between all groups. For comparisons of two groups, an unpaired Student’s t-test was used. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Localization of neutrophils in the lungs of aged mice after burn

We previously reported that neutrophils are cleared from the lungs of young mice at 24 hours after burn while these cells are persistently elevated in the lungs of aged mice receiving the same injury [31]. Multiple methods were employed to determine the pulmonary compartment in which the neutrophils are located in the lungs of young versus aged mice at 24 hours after burn. Lung sections were co-immunostained with anti-Gr-1 and anti-MOMA-2 antibodies, and Gr-1+MOMA-2− cells were considered neutrophils [32, 33]. Quantification of the number of neutrophils in lung sections from each group is shown in Table 1. At 24 hours after burn injury, there was a 4-fold increase in neutrophil numbers in aged mice subjected to burn injury compared to sham and young burn groups (p<0.05). These data further corroborate our previous study in which neutrophils in aged mice were sequestered in the lung interstitium or vasculature at 24 hours after burn injury [31]. Consistent with our previously published studies [31], lung neutrophil numbers did not differ between young sham and young burn mice 24 hours post injury (Table 1). These observations were confirmed by flow cytometry of whole lung cell suspensions. However, instead of using anti-MOMA-2 antibody for alveolar macrophages, anti-F4/80 antibody was used, since it detects circulating monocytes as well [33–35]. As shown in Table 1, while neutrophils (Gr-1hi F4/80− cells) in the lungs of young, burn-injured mice were similar to sham-injured animals, those from aged, burn-injured mice were 6 times greater than sham controls and young burn animals (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Neutrophil localization in lungs at 24 hours after burn

| Young | Aged | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Sham | Burn | Sham | Burn |

| Total # Gr-1+ MOMA-2−a cells in10 fields by immunofluorescence | 16.0 ± 2.4 | 16.1 ± 2.4 | 12.8 ± 2.5 | 63.3 ± 11.5* |

| % Gr-1+ F4/80− cellsb in lung homogenates by flow cytometry | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 11.8 ± 3.0‡ |

| % Gr-1+ F4/80− cellsc in BAL by flow cytometry | 4.1 ± 3.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 2.7 | 0.5 ± 0.2§ |

Total numbers of Gr-1+ MOMA-2− cells in lungs of young and aged animals at 24 hours after sham or burn injury were counted in sections of lung tissue. Data are shown as the average number of cells counted in ten 400x fields for each group ± SEM. N = 8-14 mice per group;

p<0.05 compared to all other groups.

All five lung lobes were homogenized in HBSS as described above. Cells were stained for Gr-1 and F4/80 as described and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are shown as the average percent of Gr-1+ F4/80− cells in the whole cell suspension ± SEM. N = 6–8 mice per group;

p<0.05 compared to all other groups.

Lungs were lavaged with 1 ml of saline until 5 ml of sample was collected. Cells were spun down and stained with Gr-1 and F4/80 as described and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are shown as the average percent of Gr-1+ F4/80− cells in BAL ± SEM,

p<0.05 compared to age-matched control.

We then sought to determine if neutrophils from either young or aged mice transmigrated and persisted in the alveolar space following burn trauma. Lungs were lavaged and BAL fluid was analyzed by flow cytometry (Table 1). As expected, BAL cells of both young and aged sham-injured mice were predominantly macrophages (F4/80+ Gr-1− cells) and did not differ between treatment groups (data not shown). Neutrophils (Gr-1hi F4/80− cells) comprised approximately 4% in the young and 7% in the aged of cells recovered from BAL as determined by flow cytometry. Interestingly, the proportion of neutrophils in the BAL decreased in both young and aged mice after burn, although this was only statistically significant in the aged burn-injured mice compared to age-matched controls (p<0.05). Together, these data indicate that the neutrophils are sequestered in the lung interstitial and/or vascular space of aged mice 24 hours after injury, but are absent in the alveolar space.

Circulating neutrophil numbers and CXCR2 expression

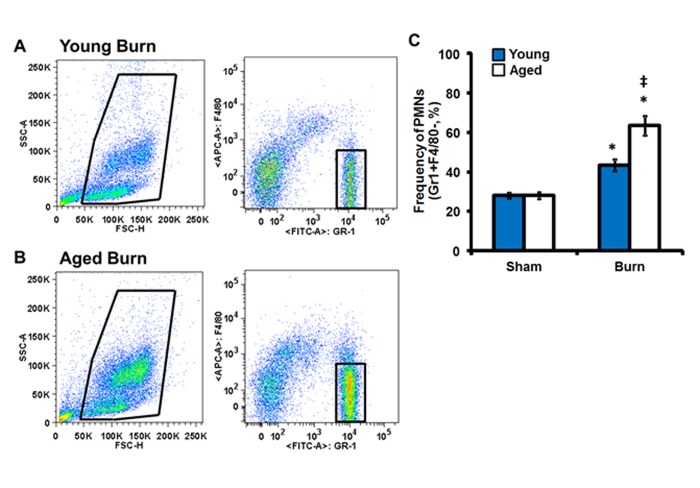

Considering the heightened accumulation of neutrophils in the lungs of aged mice, we sought to examine the peripheral blood neutrophil population as circulating numbers of neutrophils or altered expression of the chemotatic receptor, CXCR2, on neutrophils may contribute to these observations (Figure 1). Following burn injury, both young and aged mice exhibit elevated percentages of circulating neutrophils in relation to sham controls (Figure 1A–C, p<0.05). However, aged mice demonstrate a ∼20% increase in peripheral blood neutrophils as compared to young burn mice (Figure 1A–C, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood neutrophil profile. Peripheral blood cells were stained with anti-Gr-1 and anti F4/80 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative live and neutrophil (Gr-1+F4/80−) for young (A) and aged (B) mice. (C) Total neutrophil frequency in whole blood. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. N = 8–15 mice per group; *p<0.05 compared to sham controls; ‡p<0.05 compared to young burn by one-way ANOVA.

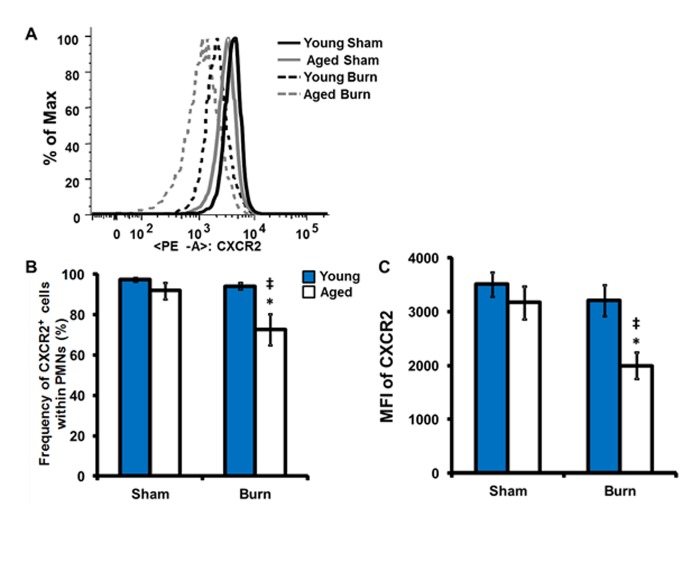

As CXCR2 mediates the neutrophil chemotatic response to KC, previously shown to be significantly elevated in lungs of aged mice 24 hours post injury [31], we sought to determine the frequency and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of CXCR2 expression in peripheral blood neutrophils (Figure 2). Interestingly, following burn injury there is a reduction in both the percentage of neutrophils expressing CXCR2 and the magnitude of CXCR2 expression in aged mice (Figure 2A–C, p<0.05). These data suggest that aging may alter the CXCR2 axis in the setting of trauma. Moreover, the prolonged elevation of KC in the lungs of aged mice at 24 hours post burn [31] may contribute to the observed downregulation of CXCR2 and alter neutrophil migration.

Figure 2.

Peripheral blood neutrophil CXCR2 expression. Peripheral blood cells were stained with anti-Gr-1, anti F4/80 antibodies and anti-CXCR2 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative histogram of CXCR2 neutrophil population with young sham- thick black, aged sham- thick gray, young burn- dotted black and aged burn- dotted gray. (B) Frequency of CXCR2+ cells within the neutrophil population; young- dark gray bars and aged- white bars. (C) Mean fluorescent intensity of CXCR2 within CXCR2+ neutrophils. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. N = 8–15 mice per group; *p<0.05 compared to sham controls; ‡p<0.05 compared to young burn by one-way ANOVA.

CXCR2-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis

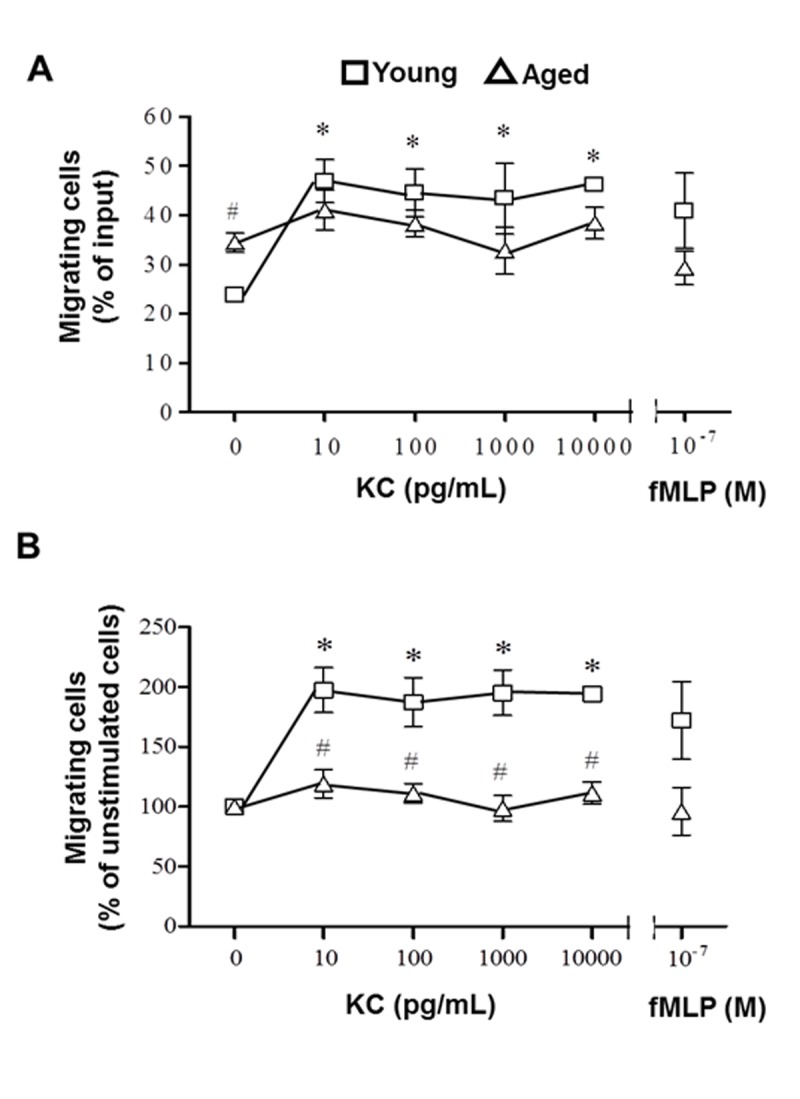

Others have shown that pretreatment of neutrophils with various inflammatory stimuli can inhibit migration through activated endothelium in vitro as a result of CXCR2 desensitization [6]. Coinciding with these studies, a basal pro-inflammatory state has been observed in the setting of advanced age and these mediators can remain elevated in aged mice in trauma models [14, 31, 36, 37]. Given the results of the previous study, we hypothesized that a migratory defect in neutrophils from aged mice may play a role in neutrophil accumulation in the lungs of aged mice after acute burn injury. Chemotaxis of isolated peripheral blood neutrophils from uninjured young and aged mice was observed in a transwell system in response to KC. This particular chemokine was chosen because our previous data indicated that there was an age-related increase between levels of KC lung homogenates and numbers of neutrophils in lung sections after burn injury [31][1]. Since pulmonary levels of MIP-2 in previous studies did not show age differences, this chemokine was not assessed. In the absence of any stimulant, migration of neutrophils from aged mice was significantly higher compared to young mice (Figure 3, p<0.05). In the presence of physiologic doses of KC, neutrophils from young mice had a robust response compared to unstimulated controls (p<0.05). However, no chemotatic response was generated in neutrophils from aged mice in response to the same increasing doses of KC. Figure 3B shows the same data re-expressed as percent control to obviate the differences in trends between the two age groups. These data suggest that neutrophils from uninjured aged mice exhibit hyperchemokinesis, but impaired directional migration in response to a stimulus. The lack of stimulus-mediated motility may be due to defects in migratory mediators downstream of CXCR2 [17, 30, 38, 38].

Figure 3.

In vitro neutrophil chemotaxis assays. Peripheral blood neutrophils isolated from young (squares) and aged (triangles) mice were tagged with CellTracker Green and incubated with varying concentrations of KC in a transwell plate for 1 hour at 37°C. fMLP was used as a positive control. Migrating cells are expressed as (A) % of input (fluorescence of migrated cells/fluorescence of input x 100) or (B) % of unstimulated cells (% input / % input of unstimulated cells x 100). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. N = 3-6 mice per group; *p<0.05 compared to young unstimulated control; #p<0.05 compared to young at the same chemokine dose by Student’s t-test.

CD62L and CD11b expression on peripheral blood neutrophils

Activation of CXCR2 helps facilitate upregulation of selectins and integrins that mediate loose and firm endothelial adherence and transmigration. Elevation of neutrophil selectins or integrins may translate into increased neutrophil adherence to the vasculature, while the observed downregulation of CXCR2 and lack of neutrophil chemotaxis may prevent transmigration in response to apical KC levels. Thus, we sought to examine neutrophil levels of CD62L and CD11b expression by flow cytometry (Table II). Despite the heightened pulmonary neutrophil congestion and impaired directional motility observed in aged mice, no difference in the frequency of CD62L and CD11b positive neutrophils was seen (data not shown). While the MFI of CD62L was reduced in both young and aged mice subjected to burn injury compared to young sham, no significant difference was noted in CD62L and CD11b expression in aged, burn-injured mice as compared young, burn-injured mice. These data suggest that alterations CD62L and CD11b expression does not contribute to the exacerbated pulmonary inflammatory response or impaired chemotaxis found with advanced age.

Table 2.

Peripheral blood neutrophil adhesion molecule expression after burn a

| CD62L | CD11b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | Burn | Sham | Burn | |

| Young | 702 ± 44 | 501± 12 * | 3404 ± 232 | 3328 ± 206 |

| Aged | 670 ± 56 | 525 ± 13 * | 3427 ± 259 | 3511 ± 398 |

CD62L and CD11b expression on peripheral blood neutrophils (F4/80− Gr-1+ cells) from young and aged mice at 24 hours after sham or burn injury was determined by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean fluorescent intensity ± SEM. N = 6-13 mice per group;

p<0.05 verse young sham by one-way ANOVA. Other data are not significant.

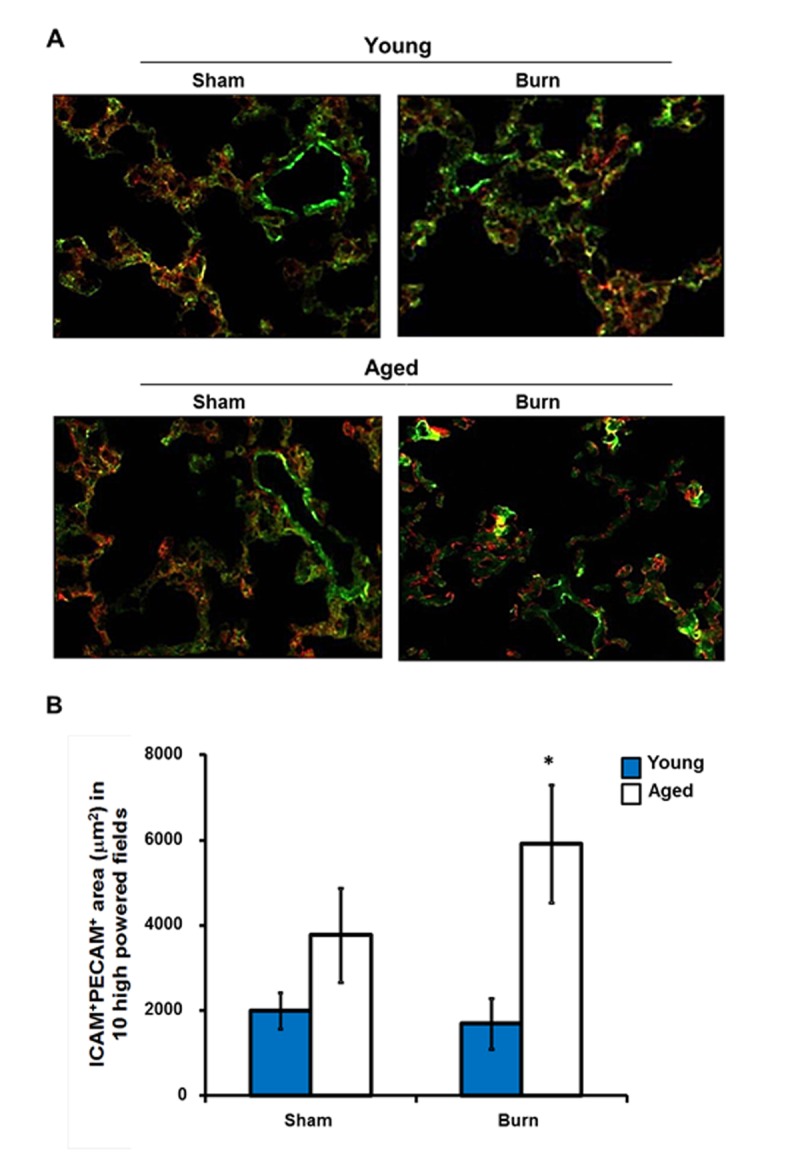

Pulmonary vascular ICAM-1 expression in response to burn injury

While no differences in CD62L and CD11b were detected, others have shown that endothelial ICAM-1 is important in neutrophil recruitment to the lungs after injury [12, 39–42]. To further investigate this in our model, lung sections were stained for ICAM-1, expressed by both pulmonary endothelial and epithelial cells, and PECAM-1, a constitutively expressed endothelial marker [43]. Colocalization of ICAM-1 and PECAM-1 was considered to be endothelial ICAM-1 expression (Figure 4A). ICAM-1 expression on the pulmonary vasculature in aged, burn-injured mice was increased greater than 3-fold compared to sham controls (p<0.05), while no differences were detected in the lungs of young, burn injured mice (Figure 4B). This suggests that pulmonary vasculature in aged mice may more readily bind activated neutrophils that are passing through the lung, subsequently leading to their retention.

Figure 4.

Pulmonary endothelial ICAM-1 expression after burn. Lung sections immunostained with anti-ICAM-1 (red) and anti-PECAM-1 (green) antibodies. (A) Representative images are shown from young and aged mice at 24 hours after sham or burn injury at 200x magnification. (B) Total ICAM-1+PECAM-1+ area (μm2) in ten high powered fields (400x). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. N=8-13 mice per group; *p<0.05 compared to young burn by one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

In summary, the data presented in this study show for the first time that neutrophils are retained in the lung vasculature and/or interstitial space of aged mice after acute burn injury and do not transmigrate into the alveolar space. This process is related, in part, to an altered pulmonary endothelial adhesion molecule profile and decreased capacity for neutrophil chemotaxis in aged mice compared to young mice at 24 hours after burn. Similar features have been shown in young animals within a few hours of injury; however, this response is transient and return to sham levels by 24 hours [42, 44, 45]. The present findings are compounded by the elevated numbers of neutrophils in the peripheral blood, which may promote enhanced congestion in the absence of adequate clearance in aged mice. The difference in pulmonary endothelial adhesion, as well as neutrophil number and function, in aged mice may contribute to the delayed resolution of the pulmonary inflammatory response as seen in our previous study [31] and might contribute to worse outcomes for this group. Taken together, these observations are important in understanding the pathogenesis of burn injury in aged individuals and suggest that prolonged inflammation may be responsible for the various complications seen in this population.

A prominent theory known as “inflamm-aging” suggests age-associated problems are related to elevations in circulating pro-inflammatory mediators in the absence of clinically detectable disease [46–48]. These findings have been corroborated by others in BAL from aged humans, in which interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 were elevated in the absence of injury or disease [49–51]. Previously, we have established that relative to young, traumatic injury in aged mice exacerbates this basal pro-inflammatory state at early time points [14, 31, 36]. Of note, a study by Luu et al. demonstrated that preincubation of neutrophils with various chemokines inhibits transmigration through an activated endothelial monolayer in vitro [21][6], suggesting that a persistent pro-inflammatory stimulus can lead to neutrophil dysregulation. Moreover, these neutrophils were able to undergo firm adhesion, but were not able to transmigrate across the endothelial layer. Interestingly, this finding was related to desensitization of the neutrophil chemotatic receptor CXCR2. Currently, our study found that following burn trauma, neutrophils from aged mice exhibit decreased expression of CXCR2. These findings recapitulate observations from human studies in which CXCR2 was downregulated in trauma patients [52, 53]. This reduction may be due to the elevated levels of circulating cytokines and chemokines [31], either through receptor desensitization or receptor ligation and uptake [38, 54, 55]. Regardless, once these neutrophils reach the pulmonary circulation, diminished CXCR2 activity may impair their ability to respond to apical chemokines to mediate transmigration through the endothelium [21, 29].

One interesting finding from this study is that peripheral blood neutrophils from aged mice have an increased ability for random migration, or chemokinesis, compared to those from young mice, as shown by others [48, 56]. Our results indicate that neutrophils from aged mice have a heightened basal level of random migration; however, their ability to respond directionally to a specific stimulus, such as KC, is impaired. While there is some contention in the literature, this idea of heightened basal neutrophil activation in aged mice parallels observations in human studies [57–59]. Advanced age has been associated with increased intracellular Ca2+ and G-protein coupled receptor kinase activation [58, 60, 61], both of which modulate neutrophil chemotatic pathways [38, 62–64][7–9]. Similar to the current study, others have shown that neutrophils from aged mice are incapable of generating a peak response once they are exposed to a secondary stimulus, such as direct KC stimulation, live bacteria, or burn injury [58, 61]. Further studies characterizing the direct role of CXCR2 in our model will potentially elucidate this mechanism.

In addition to the chemotatic role of CXCR2, reports indicate that the ability of neutrophils to signal through CXCR2 is important for adherence to and migration through endothelial layers [19, 21, 65, 66]. Activation of CXCR2 leads to upregulation and clustering of selectins, like CD62L, and integrins such as Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), lymphocyte-function associated antigen-1 (LFA-1: CD11a/CD18) and very late antigen-4 (VLA-4: CD49a/CD29) [24–26]. Specifically, signaling via CXCR2 and other chemokine pathways induce a conformational change in CD11b, allowing it to form a stronger interaction with ICAM-1 on endothelium and undergo adhesion [42, 66, 67]. Due to the differences in CXCR2 expression, we hypothesized that age may be associated with differences in adhesion molecules CD62L and CD11b. However, levels of CD62L and CD11b were found to be comparable between young and aged mice, pre- and post-burn. Additional studies are required to examine the role of CD11b clustering in this model, as well as other neutrophil integrins such as CD11a/CD18 and CD49a/CD29, to determine whether aging alters neutrophil adhesion molecules that promote firm adhesion to the pulmonary endothelium.

Another component critical to neutrophil adhesion and subsequent transmigration is the expression of various adhesion molecules by the pulmonary vasculature. Here, we demonstrate that aged mice have increased expression of pulmonary endothelial ICAM-1 and this correlates with elevated neutrophil numbers within lung tissue. Previous studies in combined trauma models have shown that loss of ICAM-1 decreases neutrophil recruitment into the lung [68], suggesting that targeting ICAM-1 may ameliorate the neutrophil congestion seen in our study. Moreover, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators can activate endothelial cells, resulting in upregulation of ICAM-1 and other adhesion molecules and a pro-adherent endothelium [17, 69, 70]. We have previously demonstrated that following burn, aged animals have elevated circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines which likely promotes upregulation of ICAM-1. Moreover, human studies have revealed the cross-linking of ICAM-1 stimulates production of IL-8, a human neutrophil chemokine [71]. This upregulation in IL-8 may be to further enhance neutrophil chemoattraction, but may also aid in the neutrophil transmigratory response to apical chemokines. Additional investigation into vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)signaling, as well as other adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, will further elucidate the impact of age and trauma on lung endothelium.

Taken together, our data suggest that a combined defect in CXCR2 signaling and elevated ICAM-1 promotes neutrophil congestion in the lungs of aged mice following burn trauma. The elevated ICAM-1 may immobilize these neutrophils within the vasculature, but their inability to adequately respond to local chemokines may prevent their eventual diapedesis and clearance. We propose that the inflammatory environment of the aged animal primes neutrophils and renders them incapable of responding appropriately to an inflammatory insult, such as burn injury. Moreover, the exacerbated pro-inflammatory environment in aged mice following burn trauma may promote an adherent phenotype within the pulmonary vasculature, further compounding the observed neutrophil defects. Understanding the mechanism involved in this process is important for identifying potential targets of therapy with the ultimate goal of improving outcomes for aged patients sustaining a burn or other traumatic injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anita Zahs, Luis Ramirez, Cory Deburghgraeve, John Karavitis and Patricia Simms for their technical assistance and Pamela Witte, PhD as head of the Immunology and Aging Program at Loyola University Medical Center for thoughtful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NIA R01 AG018859 (EJK), F30 AG029724 (VN), T32 AG031780 (PLW), the Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (EJK) and the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine MD/PhD Program.

References

- [1].Clayton MC, Solem LD, Ahrenholz DH. Pulmonary failure in geriatric patients with burns: the need for a diagnosis-related group modifier. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16:451–4. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Slater H, Gaisford JC. Burns in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:74–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ely EW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, Steinberg KP, Bernard GR. Recovery rate and prognosis in older persons who develop acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dancey DR, Hayes J, Gomez M, Schouten D, Fish J, Peters W, Slutsky AS, Stewart TE. ARDS in patients with thermal injury. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1231–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00003763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Le HQ, Zamboni W, Eriksson E, Baldwin J. Burns in patients under 2 and over 70 years of age. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;17:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Czermak BJ, Breckwoldt M, Ravage ZB, Huber-Lang M, Schmal H, Bless NM, Friedl HP, Ward PA. Mechanisms of enhanced lung injury during sepsis. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1057–65. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65358-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Czermak BJ, Friedl HP, Ward PA. Role and Regulation of Chemokines in Rodent Models of Lung Inflammation. Ilar J. 1999;40:163–166. doi: 10.1093/ilar.40.4.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sentman ML, Brannstrom T, Marklund SL. EC-SOD and the response to inflammatory reactions and aging in mouse lung. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:975–81. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xing Z, Gauldie J, Cox G, Baumann H, Jordana M, Lei XF, Achong MK. IL-6 is an antiinflammatory cytokine required for controlling local or systemic acute inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:311–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Quinton LJ, Nelson S, Zhang P, Happel KI, Gamble L, Bagby GJ. Effects of systemic and local CXC chemokine administration on the ethanol-induced suppression of pulmonary neutrophil recruitment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1198–205. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171927.66130.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Reutershan J, Basit A, Galkina EV, Ley K. Sequential recruitment of neutrophils into lung and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L807–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Reutershan J, Ley K. Bench-to-bedside review: acute respiratory distress syndrome - how neutrophils migrate into the lung. Crit Care. 2004;8:453–61. doi: 10.1186/cc2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson J, Brigham KL, Jesmok G, Meyrick B. Morphologic changes in lungs of anesthetized sheep following intravenous infusion of recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:179–86. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gomez CR, Hirano S, Cutro BT, Birjandi S, Baila H, Nomellini V, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age exacerbates the pulmonary inflammatory response after lipopolysaccharide exposure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:246–51. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251639.05135.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rojas M, Woods CR, Mora AL, Xu J, Brigham KL. Endotoxin-induced lung injury in mice: structural, functional, and biochemical responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L333–41. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00334.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schmid E, Piccolo MT, Friedl HP, Warner RL, Mulligan MS, Hugli TE, Till GO, Ward PA. Requirement for C5a in lung vascular injury following thermal trauma to rat skin. Shock. 1997;8:119–24. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199708000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Basit A, Reutershan J, Morris MA, Solga M, Rose CE, Jr, Ley K. ICAM- 1 and LFA-1 play critical roles in LPS-induced neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar space. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L200–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00346.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, Miller LH, Oppenheim JJ, Power CA. International union of pharmacology. XXII Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:145–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang XW, Liu Q, Wang Y, Thorlacius H. CXC chemokines, MIP-2 and KC, induce P-selectin-dependent neutrophil rolling and extravascular migration in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:413–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Palmieri TL, Enkhbaatar P, Bayliss R, Traber LD, Cox RA, Hawkins HK, Herndon DN, Greenhalgh DG, Traber DL. Continuous nebulized albuterol attenuates acute lung injury in an ovine model of combined burn and smoke inhalation. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1719–24. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217215.82821.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Luu NT, Rainger GE, Nash GB. Differential ability of exogenous chemotactic agents to disrupt transendothelial migration of flowing neutrophils. J Immunol. 2000;164:5961–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zarbock A, Ley K. Neutrophil adhesion and activation under flow. Microcirculation. 2009;16:31–42. doi: 10.1080/10739680802350104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Simon SI, Green CE. Molecular mechanics and dynamics of leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:151–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].de Bruyn KMT, Rangarajan S, Reedquist KA, Figdor CG, Bos JL. The Small GTPase Rap1 Is Required for Mn2+- and Antibody-induced LFA-1- and VLA-4-mediated Cell Adhesion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:29468–29476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ghandour H, Cullere X, Alvarez A, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Essential role for Rap1 GTPase and its guanine exchange factor CalDAG-GEFI in LFA-1 but not VLA-4 integrin mediated human T-cell adhesion. Blood. 2007;110:3682–3690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shimonaka M, Katagiri K, Nakayama T, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Yoshie O, Kinashi T. Rap1 translates chemokine signals to integrin activation, cell polarization, and motility across vascular endothelium under flow. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:417–427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Simon SI, Hu Y, Vestweber D, Smith CW. Neutrophil tethering on E-selectin activates beta 2 integrin binding to ICAM-1 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Immunol. 2000;164:4348–4358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Simon SI, Cherapanov V, Nadra I, Waddell TK, Seo SM, Wang Q, Doerschuk CM, Downey GP. Signaling functions of L-selectin in neutrophils: alterations in the cytoskeleton and colocalization with CD18. J Immunol. 1999;163:2891–2901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rot A, Hub E, Middleton J, Pons F, Rabeck C, Thierer K, Wintle J, Wolff B, Zsak M, Dukor P. Some aspects of IL-8 pathophysiology. III: Chemokine interaction with endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:39–44. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Molteni R, Crespo CL, Feigelson S, Moser C, Fabbri M, Grabovsky V, Krombach F, Laudanna C, Alon R, Pardi R. {beta}-Arrestin 2 is required for the induction and strengthening of integrin-mediated leukocyte adhesion during CXCR2-driven extravasation. Blood. 2009;114:1073–1082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nomellini V, Faunce DE, Gomez CR, Kovacs EJ. An age-associated increase in pulmonary inflammation after burn injury is abrogated by CXCR2 inhibition. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1493–501. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sugimoto Y, Katayama N, Masuya M, Miyata E, Ueno M, Ohishi K, Nishii K, Takakura N, Shiku H. Differential cell division history between neutrophils and macrophages in their development from granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:725–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Vermaelen K, Pauwels R. Accurate and simple discrimination of mouse pulmonary dendritic cell and macrophage populations by flow cytometry: methodology and new insights. Cytometry A. 2004;61:170–77. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Austyn JM, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11:805–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hirsch S, Austyn JM, Gordon S. Expression of the macrophage-specific antigen F4/80 during differentiation of mouse bone marrow cells in culture. J Exp Med. 1981;154:713–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nomellini V, Gomez CR, Gamelli RL, Kovacs EJ. Aging and animal models of systemic insult: trauma, burn, and sepsis. Shock. 2009;31:11–20. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180f508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gomez CR, Nomellini V, Baila H, Oshima K, Kovacs EJ. Comparison of the effects of aging and IL-6 on the hepatic inflammatory response in two models of systemic injury: scald injury versus I.p. LPS administration. Shock. 2009;31:178–84. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180feb8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nguyen-Jackson H, Panopoulos AD, Zhang H, Li HS, Watowich SS. STAT3 controls the neutrophil migratory response to CXCR2 ligands by direct activation of G-CSF-induced CXCR2 expression and via modulation of CXCR2 signal transduction. Blood. 2010;115:3354–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mulligan MS, Till GO, Smith CW, Anderson DC, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Todd RF, 3rd, Issekutz TB, Ward PA. Role of leukocyte adhesion molecules in lung and dermal vascular injury after thermal trauma of skin. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1008–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Doerschuk CM, Quinlan WM, Doyle NA, Bullard DC, Vestweber D, Jones ML, Takei F, Ward PA, Beaudet AL. The role of P-selectin and ICAM-1 in acute lung injury as determined using blocking antibodies and mutant mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:4609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lo SK, Everitt J, Gu J, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor mediates experimental pulmonary edema by ICAM-1 and CD18-dependent mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:981–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI115681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jin RB, Zhu PF, Wang ZG, Liu DW, Zhou JH. Changes of pulmonary intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and CD11b/CD18 in peripheral polymorphonuclear neutrophils and their significance at the early stage of burns. Chin J Traumatol. 2003;6:156–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Eppihimer MJ, Russell J, Langley R, Vallien G, Anderson DC, Granger DN. Differential expression of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) in murine tissues. Microcirculation. 1998;5:179–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Baskaran H, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Dynamics of tissue neutrophil sequestration after cutaneous burns in rats. J Surg Res. 2000;93:88–96. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Piccolo MT, Wang Y, Sannomiya P, Piccolo NS, Piccolo MS, Hugli TE, Ward PA, Till GO. Chemotactic mediator requirements in lung injury following skin burns in rats. Exp Mol Pathol. 1999;66:220–6. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1999.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bonafe M, Olivieri F, Cavallone L, Giovagnetti S, Mayegiani F, Cardelli M, Pieri C, Marra M, Antonicelli R, Lisa R, Rizzo MR, Paolisso G, Monti D, Franceschi C. A gender--dependent genetic predisposition to produce high levels of IL-6 is detrimental for longevity. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2357–61. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2357::aid-immu2357>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mahbub S, Brubaker AL, Kovacs EJ. Aging of the Innate Immune System: An Update. Curr Immunol Rev. 2011;7:104–115. doi: 10.2174/157339511794474181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Meyer KC, Soergel P. Variation of bronchoalveolar lymphocyte phenotypes with age in the physiologically normal human lung. Thorax. 1999;54:697–700. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Meyer KC, Rosenthal NS, Soergel P, Peterson K. Neutrophils and low-grade inflammation in the seemingly normal aging human lung. Mech Ageing Dev. 1998;104:169–81. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Meyer KC, Ershler W, Rosenthal NS, Lu XG, Peterson K. Immune dysregulation in the aging human lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1072–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tarlowe MH, Duffy A, Kannan KB, Itagaki K, Lavery RF, Livingston DH, Bankey P, Hauser CJ. Prospective study of neutrophil chemokine responses in trauma patients at risk for pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:753–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-917OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cummings CJ, Martin TR, Frevert CW, Quan JM, Wong VA, Mongovin SM, Hagen TR, Steinberg KP, Goodman RB. Expression and function of the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:2341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nasser MW, Raghuwanshi SK, Malloy KM, Gangavarapu P, Shim JY, Rajarathnam K, Richardson RM. CXCR1 and CXCR2 activation and regulation. Role of aspartate 199 of the second extracellular loop of CXCR2 in CXCL8-mediated rapid receptor internalization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6906–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mueller SG, White JR, Schraw WP, Lam V, Richmond A. Ligand-induced desensitization of the human CXC chemokine receptor-2 is modulated by multiple serine residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8207–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Panda A, Arjona A, Sapey E, Bai F, Fikrig E, Montgomery RR, Lord JM, Shaw AC. Human innate immunosenescence: causes and consequences for immunity in old age. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schroder AK, Rink L. Neutrophil immunity of the elderly. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:419–25. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wenisch C, Patruta S, Daxbock F, Krause R, Horl W. Effect of age on human neutrophil function. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:40–5. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].De Martinis M, Modesti M, Ginaldi L. Phenotypic and functional changes of circulating monocytes and polymorphonuclear leucocytes from elderly persons. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:415–20. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schutzer WE, Reed JF, Bliziotes M, Mader SL. Upregulation of G protein-linked receptor kinases with advancing age in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R897–903. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.3.R897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Fulop T, Larbi A, Douziech N, Fortin C, Guerard KP, Lesur O, Khalil A, Dupuis G. Signal transduction and functional changes in neutrophils with aging. Aging Cell. 2004;3:217–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Vroon A, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. GRKs and arrestins: regulators of migration and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1214–21. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pitcher JA, Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:653–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Adams JM, Hauser CJ, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Fekete Z, Deitch EA. Early trauma polymorphonuclear neutrophil responses to chemokines are associated with development of sepsis, pneumonia, and organ failure. J Trauma. 2001;51:452–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200109000-00005. discussion 456–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Laudanna C, Alon R. Right on the spot. Chemokine triggering of integrin-mediated arrest of rolling leukocytes. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Beck-Schimmer B, Madjdpour C, Kneller S, Ziegler U, Pasch T, Wuthrich RP, Ward PA, Schimmer RC. Role of alveolar epithelial ICAM-1 in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:1142–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00236602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bird MD, Morgan MO, Ramirez L, Yong S, Kovacs EJ. Decreased pulmonary inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury in intercellular adhesion molecule-1 knockout mice. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:652–660. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181e4c58c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Matsutani T, Kang SC, Miyashita M, Sasajima K, Choudhry MA, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Liver cytokine production and ICAM-1 expression following bone fracture, tissue trauma, and hemorrhage in middle-aged mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G268–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Subauste MC, Choi DC, Proud D. Transient exposure of human bronchial epithelial cells to cytokines leads to persistent increased expression of ICAM-1. Inflammation. 2001;25:373–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1012850630351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sano H, Nakagawa N, Chiba R, Kurasawa K, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Cross-linking of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 induces interleukin-8 and RANTES production through the activation of MAP kinases in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:694–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Walker HL, D. MA., Jr A standard animal burn. J Trauma. 1968;8:1049–51. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on cellular immune responses in a murine model of thermal injury. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:733–40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cook VL, Neuder LE, Blikslager AT, Jones SL. The effect of lidocaine on in vitro adhesion and migration of equine neutrophils. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;129:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Boehmer ED, Meehan MJ, Cutro BT, Kovacs EJ. Aging negatively skews macrophage TLR2- and TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory responses without affecting the IL-2-stimulated pathway. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:1305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Mahbub S, Deburghgraeve CR, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age impairs macrophage polarization. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011. [Epub before print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]