Abstract

Eight new ruthenium complexes of clotrimazole (CTZ) with high antiparasitic activity have been synthesized, cis,fac-[RuIICl2(DMSO)3(CTZ)] (1), cis,cis,trans-[RuIICl2(DMSO)2(CTZ)2] (2), Na[RuIIICl4(DMSO)(CTZ)] (3) and Na[trans-RuIIICl4(CTZ)2] (4), [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CTZ)] (5), [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(bipy)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (6), [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(en)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (7) and [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(acac)(CTZ)][BF4] (8) (bipy = bipyridine; en = ethlylenediamine; acac = acetylacetonate). The crystal structures of compounds 4-8 are described. Complexes 1-8 are active against promastigotes of Leishmania major and epimastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Most notably complex 5 increases the activity of CTZ by factors of 110 and 58 against L. major and T. cruzi, with no appreciable toxicity to human osteoblasts, resulting in nanomolar and low micromolar lethal doses and therapeutic indexes of 500 and 75, respectively. In a high-content imaging assay on L. major infected intraperitoneal mice macrophages, complex 5 showed significant inhibition on the proliferation of intracellular amastigotes (IC70 = 29 nM), while complex 8 displayed some effect at a higher concentration (IC40 = 1 μM).

INTRODUCTION

Parasitic trypanosomatids are the origin of human ailments such as leishmaniasis and Chagas’ disease, caused by the Leishmania genus and Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi), respectively. Leishmaniasis is encountered in tropical and subtropical regions of the world and transmitted by certain species of the sand fly (subfamily Phlebotominae). Over 20 species and subspecies of Leishmania infect humans, causing three varieties of the disease: visceral (VL), cutaneous (CL) and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL). About 350 million people are at risk in 88 countries; an estimated 12 million people are currently infected and around 2 million new infections occur each year, with a third of the global cases being attributable to cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The American trypanosome, on the other hand, causes Chagas’ disease, which afflicts up to 20 million people with different forms of the pathology in Central and South America. About 5 million are expected to develop severe cardiomyopathy and/or digestive disorders and up to 50,000 people die annually from these complications.2 The human infection begins when the metacyclic trypomastigote form of the parasite, present in the Triatominae insect vector's feces, invades the host blood through the insect bite wound or nearby mucosa.2c Other major routes of transmission are blood transfusion and organ transplant from infected donors, as well as congenital transmission, which is making Chagas’ disease emerge as a serious problem in blood and tissue banks in the U.S., Canada and Europe, due to immigration from endemic countries.3

Most of the available treatments for both diseases are 20 or more years old and they are characterized by high toxicity and limited efficacy:4,5 Antimonials (meglumine or antimoniate), amphotericin B or pentamidine for leishmaniasis, and azole or nitro derivatives (benznidazole or nifurtimox) in the case of Chagas’ disease. In addition, the vast majority of people afflicted by such diseases do not have the resources to cover the cost of full therapies and therefore pharmaceutical companies find little incentives to develop new drugs. To make matters worse, the emergence of resistant strains to current treatments6,7 clearly states the urgent need for new and effective drugs to treat trypanosomatid infections.

Azole-type molecules have been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of trypanosomes thanks to their ability to act as sterol biosynthesis inhibitors (SBIs), which block the proliferation of parasites by inhibiting the cytochrome P-450 dependent C-14-α-demethylation of lanosterol to ergosterol;4, 8 some of them, e.g. posaconazole and ravuconazole, are expected to enter clinical trials in the short term. Clotrimazole (CTZ) and ketoconazole (KTZ), well known as antifungal agents, also display some anti-T.cruzi activity. The sterol biosynthetic pathways of Trypanosoma and Leishmania are similar to those of pathogenic fungi and therefore their growth is susceptible to sterol biosynthesis inhibitors (SBIs), providing the rationale for the success of these compounds as potent new antiparasitic agents.9

An attractive concept that some of us have proposed is the metal-drug synergism, achieved through the combination of a molecule of known biological activity with a metal- containing fragment;10 such combinations can translate into an enhanced activity of the parental drug, together with a decrease of its toxicity. In addition, the use of metal-based drugs allows the design of chemical entities capable of reaching a variety of specific targets.11,12,13,14 In early work we reported metal complexes of CTZ and KTZ with Ru, Rh, Pt, Au and Cu, some of which displayed high activity against T. cruzi.15 The most efficacious compound was RuCl2(CTZ)2, which produced a 10-fold increase in activity when compared to free CTZ, accompanied by a notable 10-fold decrease in toxicity against normal mammalian (Vero) cells. A synergistic mechanism of action, involving the liberation of CTZ at the site of action to exert its regular SBI function, coupled with a covalent interaction of the remaining metal-containing fragment to the parasite's DNA to produce nuclear damage, is responsible for the behavior of RuCl2(CTZ)215b. Nevertheless, the low solubility of these compounds in aqueous media translated into poor activities in vivo. We also extended the success of the metal-drug synergism to the case of malaria, through a number of metal-chloroquine complexes that are able to overcome resistance to chloroquine in a variety of strains of Plasmodium falciparum.10, 16

Using a similar approach, other potential metal-based drugs for Chagas’ disease have been described; parasitic cysteine proteases like cruzain and cathepsin B,12 as well as trypanothione reductase13 have been mentioned as possible additional targets for metal-based antiparasitic drugs. Pd, Pt, and Ru complexes with bioactive nitrofuran-containing thiosemicarbazone or pentamidine ligands displayed higher in vitro activity than the corresponding ligands or the first line treatment nifurtimox against T. cruzi and T. brucei.17 These complexes may act through multiple-target mechanisms probably involving free radicals and/or binding to cruzipain or trypanothione reductase, but not to DNA. Other recently reported metal complexes with anti T. cruzi activity include Pt and Pd derivatives of pyridine-2-thiol-N-oxide,18 a vanadyl complex and a series of Ru nitrothiosemicarbazones containing DNA intercalating ligands,19 Ru-aryl-4-oxothiazolylhydrazones,20 Pt- and Pd-dithiocarbazates,21 Mn-, Co-, Ni- and Cu-risedronates,22 Co and Cu complexes with the triazole ligand 5-methyl-1,2,4- triazolo[1,5-a] pyrimidin-7(4H)-one (HmtpO),23 and fluoroquinolones coordinated to Mn, Co and Cu.24

In contrast, the search for new more effective and less toxic metal-based therapies for leishmaniasis has received much less attention. Complexes of Rh, Ir or Cu with pentamidine or dppz (dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine), and of Pt with terpyridine and other DNA-intercalating ligands,10,11,25 have shown interesting activity. Silver polypyridyl derivatives targeting DNA also showed leishmanicidal effects26 and Ag nanoparticles encapsulated in ferritin molecules produced an antripoliferative effect on Leishmania infantum by inhibiting trypanothione reductase.27 Cu and Zn derivatives of N-quinolin-8-yl-arylsulfonamides also displayed activity against L. brasiliensis and L. chagasi.28 Clearly, the discovery of new metal-based drugs for the chemotherapy of leishmaniasis is highly desirable.

In this paper we report the synthesis of a new series of compounds that combine CTZ with ruthenium, along with their activity against Leishmania major (L. major) and Trypanosoma cruzi, and the evaluation of their toxicity against normal human osteoblasts. Ruthenium is an attractive alternative for medicinal applications, due to the low toxicity displayed by compounds of this metal, as a result of the ability of Ru to mimic the binding of iron to biomolecules such as transferrin and albumin.14 Two molecular designs were envisaged, aiming for a dual target mechanism (SBI action plus selective DNA binding): (i) Octahedral RuII and RuIII coordination complexes [RuIICl2(DMSO)3(CTZ)] (1), [RuIICl2(DMSO)2(CTZ)2] (2), Na[RuIIICl4(DMSO)(CTZ)] (3) and Na[RuIIICl4(CTZ)2] (4); and (ii) Organometallic “piano-stool” arene-RuII-CTZ compounds [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CTZ)] (5), [RuII(η6-p- cymene)(bipy)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (6), [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(en)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (7) and [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(acac)(CTZ)][BF4] (8) (bipy = bipyridine; en = ethlylenediamine; acac = acetylacetonate). The ancillary ligands provide the desired stability and modulate the physicochemical properties of the drugs in order to optimize the biological properties.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry

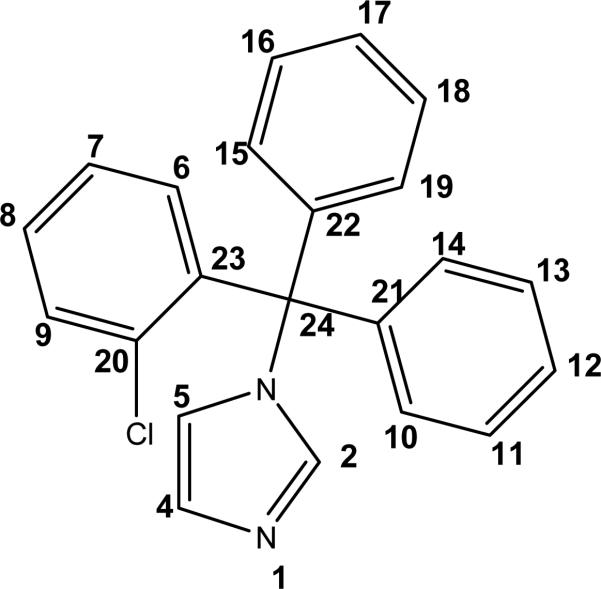

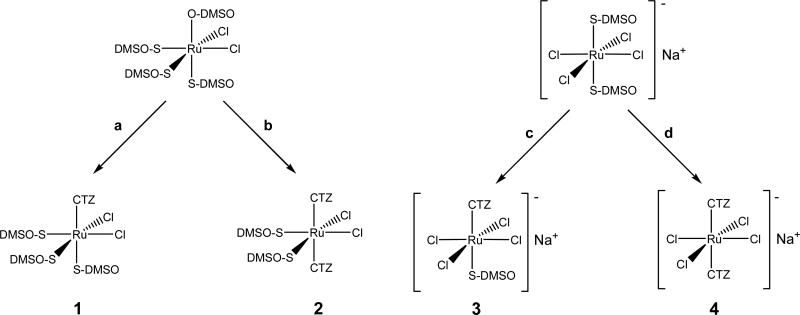

CTZ is a classic imidazole ligand with a single coordination site (N1) capable of binding a metal atom (Figure 1). The new RuII and RuIII octahedral complexes 1-4 were prepared as depicted in Scheme 1. cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)4] reacts smoothly with 1 or 2 eq. of CTZ in methanol to yield the neutral complexes [RuIICl2(DMSO)3(CTZ)] (1) and [RuIICl2(DMSO)2(CTZ)2] (2), respectively,as air-stable yellow powders. The cis,fac- geometry for 1 and cis,cis,trans- for 2 were confirmed by NMR and FT-IR spectroscopies: The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 shows signals typical of N-coordinated CTZ, i.e. H2, H4 and H5 shifted 1.04, 0.76 and 0.07 ppm, with respect to the free ligand.15 The presence of three singlets in the DMSO region of the 1H NMR, each one integrating for one DMSO molecule, indicates that CTZ has replaced one DMSO molecule in cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)4], most likely the O-bonded one (Scheme 1, a).29 This is confirmed by elemental analysis and by the presence of IR bands assigned to ν(Ru-S) at 421 cm-1 and ν(S-O) at 1091 cm-1, typical of S-coordinated DMSO, and the absence of ν(Ru-O).29 Other known reactions of cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)4] with imidazoles30 and the extreme conditions required for a potential cis3trans isomerization31 allow us to assign the cis conformation of the chlorides in 1. Finally, the observation of NOE effects between the methyl groups of all three DMSO molecules in the 1H-1H NOESY experiments (data not shown) confirms their fac arrangement.

Figure 1.

Clotrimazole (CTZ) with atom labeling.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of complexes 1-4: (a) 1 CTZ, MeOH, r.t.; (b) 2 CTZ, MeOH, r.t.; (c) 1 CTZ, MeOH, r.t.; (d) 3 CTZ, MeOH, r.t.

The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 shows a very similar pattern to that of 1. The N1 coordination of the imidazole ring of CTZ induces a shift of 0.86 and 0.56 ppm for H2 and H4, respectively. There is a single set of signals for the two CTZ ligands and one for the four methyl groups of the DMSO molecules, suggesting a cis configuration for the two chlorides, cis for the two DMSO molecules, and trans for the two CTZ molecules. In this spatial arrangement two planes of symmetry and a C2 axis make the two DMSO and the two CTZ molecules chemically and magnetically equivalent, in agreement with the NMR observations. This stereochemistry is in contrast with the cis,cis,cis one proposed for analogous complexes of 1,2-dimethyl imidazole32 and 1,5,6-trimethylimidazole.33 It is reasonable to assume that the trans conformation is preferred for 2 in order to minimize steric repulsions between the two bulky CTZ ligands. The FT-IR spectrum shows ν(S-O) at 1090 cm-1 and ν(Ru-S) at 421 cm-1, indicating a coordination of both DMSO molecules through the S atom.

Complexes 3 and 4 were prepared by reacting Na[trans-RuIIICl4(DMSO)2] with the appropriate amounts of CTZ in methanol at room temperature. Since Ru(III) is paramagnetic, the characterization of these compounds relies on elemental analysis and FT-IR spectroscopy. The results agree with the proposed structures. As seen in similar reactions,34 CTZ replaces one of the DMSO molecules in complex 3 to yield a CTZ analogue of the anti-metastatic agent NAMI. The coordination of the DMSO remains through S as in the starting material, as shown by the presence of ν(Ru-S) at 421 cm-1 and ν(S-O) at 1090 cm-1 plus the absence of ν(Ru-O). A similar analysis can be made for complex 4. The elemental analysis confirms the presence of four chlorides and two molecules of CTZ. The trans geometry is proposed in view of the steric bulk of the CTZ ligands, in parallel to the antitumor agent KP1019 and related derivatives.35

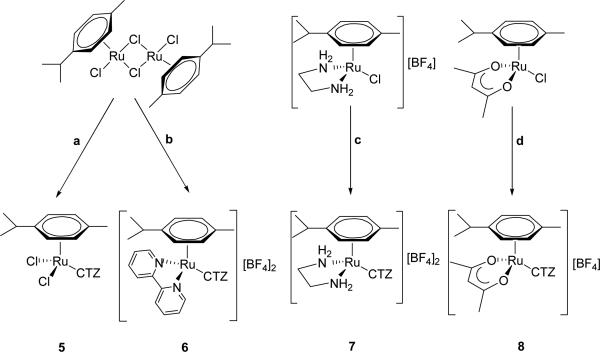

The set of organoruthenium-CTZ complexes 5-8 on the other hand, was synthesized by reaction of CTZ with adequate starting materials (see Scheme 2). The presence of the arene ligand provides stability, together with tunable physicochemical features through the combination with other relevant ligands in the coordination sphere of the metal atom. The molecular structures of these four new complexes were determined by X-ray diffraction and are shown in Fig. 2. Crystallographic details are contained in Table 3 (Experimental Section).

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of complexes 5-8. (a) 2 CTZ, Me2CO, rt; (b) i. 4 AgBF4, Me2CO, rt, ii. 2 bipy, Me2CO, rt, iii. 2 CTZ, rt; (c) i. AgBF4, Me2CO, rt, ii. CTZ, CH2Cl2/Me2CO 1:1, rt; (d) i. AgBF4, Me2CO, rt, ii. CTZ, CH2Cl2, rt. For details, see Experimental Section.

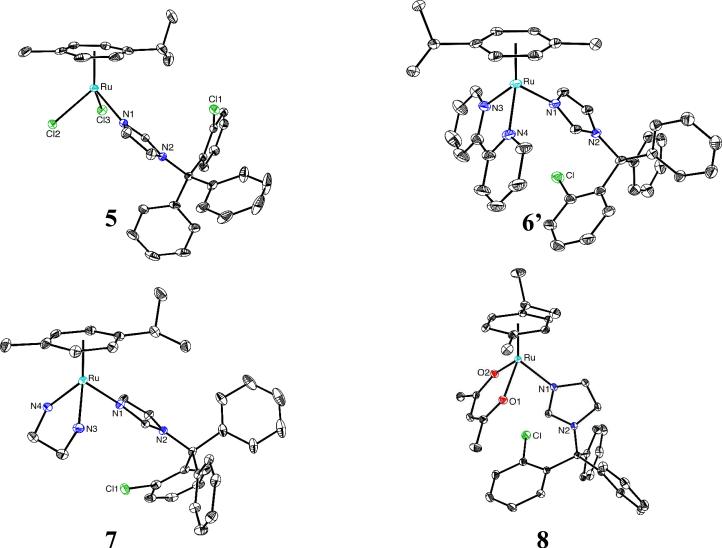

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of complex 5 and the cations of complexes 6’-8 (hydrogen atoms, counterions and solvent molecules omitted for clarity).

Table 3.

Crystal, intensity collection and refinement data

| [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CTZ)] (5) | [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(bipy) (CTZ)] [picrate]2 (6’) | [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(en)(CTZ)] [BF4]2 (7) | [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(acac)(CTZ)] [BF4] (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Triclinic | Monoclinic |

| Formula | C32H3lCl3N2Ru | C54H44.31C1N10O14.64Ru | C35H4lB2Cl3F8N4Ru | C37H38BClF4N2O2Ru |

| Formula weight | 651.01 | 1204.04 | 898.76 | 766.02 |

| Space group | P21/n | C2/c | P21/n | |

| a / Å | 10.6482(9) | 24.128(6) | 8.9364(10) | 11.6986(7) |

| b / Å | 13.9927(11) | 16.765(4) | 11.7146(13) | 18.9176(12) |

| c / Å | 19.5109(15) | 28.339(9) | 19.341(2) | 15.1412(10) |

| α / ° | 90 | 90 | 101.146(2) | 90 |

| β / ° | 102.5130(10) | 112.796(3) | 100.106(2) | 90.1030(10) |

| γ / ° | 90 | 90 | 97.961(2) | 90 |

| V / Å3 | 2838.0(4) | 10568(5) | 1924.3(4) | 3350.9(4) |

| Z | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| Temperature (K) | 150(2) | 150(2) | 150(2) | 150(2) |

| Radiation (λ, Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| ρ (cald.) Mg/m3 | 1.524 | 1.513 | 1.551 | 1.518 |

| Absn. Coeff. / mm-1 | 0.860 | 0.427 | 0.687 | 0.607 |

| F(000) | 1328 | 4931 | 912 | 1568 |

| Crystal size / mm | 0.13 × 0.10 × 0.05 | 0.32 × 0.17 × 0.17 | 0.30 × 0.25 × 0.25 | 0.24 × 0.20 × 0.20 |

| θ range, deg. | 1.81 to 31.75° | 1.53 to 30.51° | 1.81 to 31.00° | 1.72 to 32.74° |

| Reflections collected | 48314 | 82342 | 32050 | 57659 |

| Indep. reflections | 9604 (Rint = 0.0922) | 16106 (Rint = 0.1365) | 12180 (Rint = 0.0358) | 11842 (Rint = 0.0400) |

| R1 [I>2σ(I)] | 0.0496 | 0.0735 | 0.0416 | 0.0390 |

| wR2 | 0.0979 | 0.1866 | 0.0985 | 0.0965 |

| R1 (all data) | 0.0955 | 0.1506 | 0.0525 | 0.0533 |

| wR2 (all data) | 0.1148 | 0.2282 | 0.1032 | 0.1040 |

| GOF | 1.026 | 1.062 | 1.011 | 1.045 |

All complexes display similar “piano-stool” configurations with the p-cymene ligand occupying three coordination sites; the N1 atom of CTZ plus two other donor atoms from the remaining ligands complete the pseudo-octahedral coordination around the ruthenium atom. The main structural features as well as the values of relevant bond lengths and angles, listed in Table 1, are within the normal range for similar known complexes, e.g. [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(en)][PF6]36, [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(NO2)(bipy)][PF6]37 and [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(acac)].38 The structures of other (p-cymene)RuII(imidazole) complexes39 are also comparable, including Ru-N distances ranging between 2.10 and 2.14 Å. Moreover, the Ru-N bond distances observed for 5-8 compare well with those of closely related complexes previously described by us, namely 2.03 Å in RuCl2(BTZ)2 (BTZ being the bromo analogue of CTZ)15b and about 2.0 Å in [Cu(CTZ)4]Cl215d. 1D and 2D 1H and 13C NMR studies in solution, as well as elemental analyses and FT-IR spectra (see Experimental Section) agree with the crystal structures in all cases.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (in Å) and angles (in deg) for complexes 5-8.

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru-N1 | 2.098(2) | 2.083(4) | 2.097(2) | 2.112(2) |

| Ru-X | 2.4118(8) 2.3991(9) |

2.091(3) 2.079(4) |

2.156(6) 2.110(5) |

2.070(1) 2.074(1) |

| Arcen-Ru | 1.664 | 1.690 | 1.674 | 1.662 |

| X-Ru-N1 | 84.14(6) 85.23(7) |

82.0(1) 87.5(1) |

87.0(2) 85.9(2) |

83.83(6) 84.39(6) |

| X-Ru-X | 88.65(3) | 77.8(1) | 79.0(2) | 88.02(5) |

| Arcen-Ru-X | 127.55 128.44 |

132.94 131.82 |

127.95 132.56 |

127.26 125.85 |

| Arcen-Ru-N1 | 128.05 | 126.67 | 127.68 | 132.30 |

X = Cl, N(bipy), N(en), O(acac)

In vitro antiparasitic activity and cytoxicity

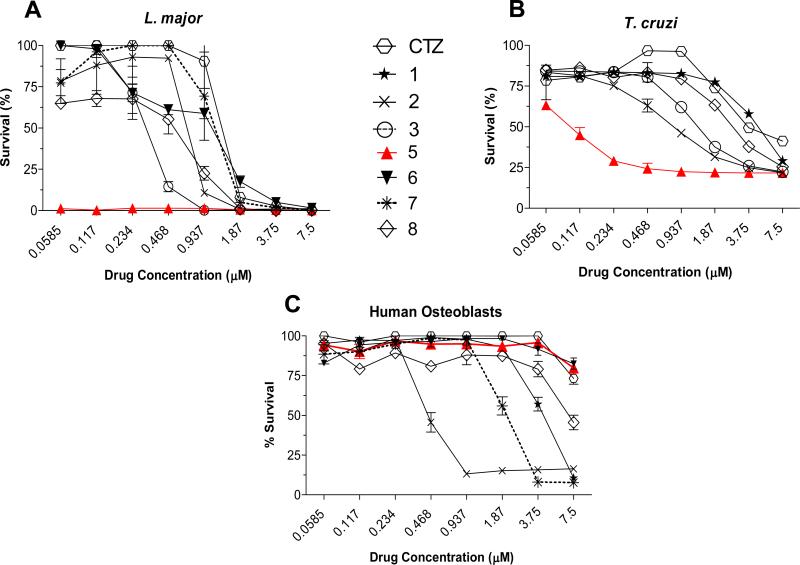

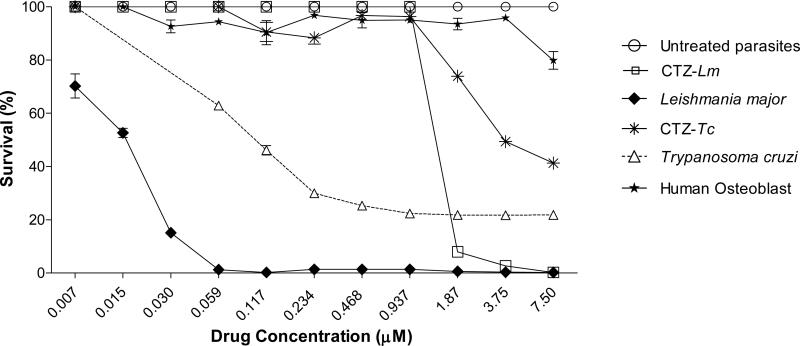

The effect of the new metal complexes 1-8 on the proliferation of in vitro cultures of promastigotes of L. major and epimastigotes of T. cruzi, was tested in comparison with CTZ and with Ru compounds of similar structure not containing CTZ, namely Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)2] (C1), cis-[RuCl2(DMSO)4] (C2) and [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (C3) (for details, see Experimental Section). The results are collected in Table 2 and Figure 3. The cytotoxic impact on human osteoblasts was also monitored in order to establish the potential toxicity of the compounds against normal cells (Table 2 and Figures 3C and 4). Complex 5 in particular displays a remarkably high activity against both parasites with LD50 values in the sub-micromolar range against L. major and T. cruzi, respectively, that is, 110 and 58 times more active than free CTZ in each case; also importantly, compound 5 does not display any appreciable toxicity to human osteoblasts when assayed up to 7.5 μM, which represents excellent therapeutic indexes greater than 500 and 75 for L. major and for T. cruzi, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Table 2.

In vitro antiparasitic activity of controls and complexes 1-8 against promastigotes of L. major and epimastigotes of T. cruzi, and cytotoxic impact on human osteoblasts (p-value < 0.0001). See Experimental Section for details.

| Compound | LD50 L. major (μM)1 [Rel. Act.]2 / (T.I.)3 | LD50 T. cruzi (μM)1 (Rel. Act.)2 | IC50 Mammalian cells (μM)4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promastigotes | Epimastigotes | Human osteoblast | |

| C1 | 15.36± 3.68 [0.10] / (> 0.5) | > 30 [< 0.2] | > 7.5 |

| C2 | 13.23 ± 4.48 [0.12] / (> 0.6) | > 30 [< 0.2] | > 7.5 |

| C3 | 12.52 ± 3.34 [0.13] /(> 0.6) | > 30 [< 0.2] | > 7.5 |

| CTZ | 1.6 ± 0.5 [1.0] / (>4.7) | 5.8 ± 1.7 [1.0] / (> 1.3) | > 7.5 |

| 1 | > 7.5 [< 0.2] / (< 0.5) | 4.8 ± 1.9 [1.2] / (0.81) | 3.9 ± 1.2 |

| 2 | 0.7 ± 0.3 [2.3] / (0.7) | 1.1 ± 0.5 [5.3] / (0.5) | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 [5.3] / (2.0) | 1.6 ± 0.5 [3.6] / (0.4) | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 2.76 ± 0.45 [0.58] / (2.1) | 5.43 ± 0.36 [1.1] / (1.1) | 5.9 ± 1.0 |

| 5 | 0.015 ± 0.004 [110] / (>500) | 0.1 ± 0.4 [58] / (>75) | > 7.5 |

| 6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 [1.1] / (>5.4) | >> 7.5 [< 0.8] / (<1) | > 7.5 |

| 7 | 1.32 ± 0.69 [1.2] / (1.7) | 7.7 ± 0.1 [0.75] / (0.3) | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| 8 | 0.45 ± 0.15 [3.6] / (15) | 2.9 ± 0.4 [2.0] / (2.3) | 6.55 ± 1.69 |

LD50: Median lethal dose calculated with 95% Confidence Interval; ± values are the estimated LD50 interval.

[Rel. Act.]: Realative Activity (LD50 of CTZ)/(LD50 of Ru-CTZ complex)

T.I.: Therapeutic index (IC50 in mammalian cells)/(LD50 in parasites)

IC50: Median inhibitory concentration

Figure 3.

Effect of CTZ and selected Ru-CTZ complexes on the proliferation of (A) promastigotes of L. major, (B) epimastigotes of T. cruzi and (C) human osteoblasts. Activity data for metal controls and all Ru-CTZ complexes can be found in Table 2.

Figure 4.

In vitro antiparasitic activity of complex 5 against promastigotes of L. major and epimastigotes of T. cruzi. Effect of the effective range concentrations on human osteoblasts. CTZ-Lm, promastigotes of L. major treated with clotrimazole; CTZ-Tc, epimastigotes of T. cruzi treated with clotrimazole. Human osteoblasts were treated with the standard therapeutic concentration of benznidazol (reference drug to treat T. cruzi infection). See Experimental Section for details.

Other interesting observations can be made from the results in Figure 3 and Table 2. None of the reference metal compounds not containing CTZ (C1-C3) show any appreciable antiparasitic effect within the concentration range tested, while most Ru-CTZ complexes significantly enhance the activity of the parental drug CTZ. This evidences that it is the combination of CTZ and the metal3containing moiety in a single molecule that results in a synergistic effect that notably enhances the antiproliferative activity. The incorporation of the metal center results in critical modifications of the physicochemical properties of the drug, thus providing adequate transport properties to the target. It is also likely to open a second or alternative mechanism not available for CTZ itself, possibly selective DNA binding.

Although with the data at hand no clear structure-activity trends can be established, the pattern of efficacy follows the order 5 >> 8 > 7 > 6 in the case of the organometallic compounds for both L. major and T. cruzi. However, no specific tendencies are observed for the octahedral coordination complexes 1-4.

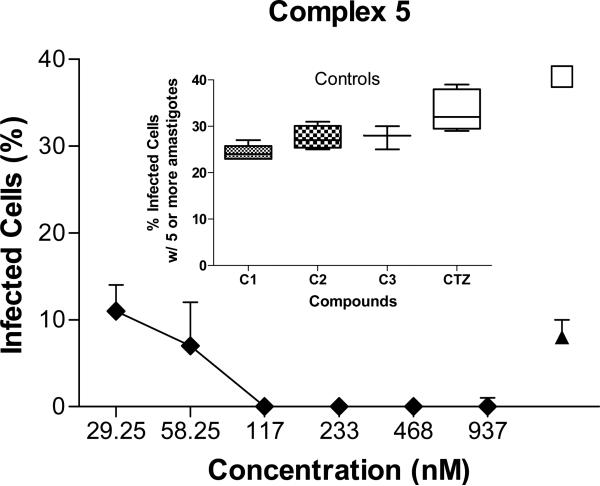

In view of these results, the activity of complexes 5 and 8 was further tested against amastigotes of L. major, the infectious intracellular form of the parasite, which is of more therapeutic relevance. A high-content imaging assay (HCIA) was performed on L. major infected intraperitoneal mice macrophages, following the method described in the Experimental Section. As shown in Fig. 5, complex 5 showed significant inhibition on the proliferation of intracellular amastigotes (IC70 = 29 nM). Complex 8 also displayed some effect using a higher concentration (IC40 = 1 μM, data not shown); for comparison, the standard drug amphotericin B causes a similar effect only at concentrations of 5 μM (Fig. 5), while neither free CTZ, nor the metal controls C1-C3 displayed any significant activity at concentrations as high as 1 μM.

Figure 5.

Effect of complex 5 on the proliferation of L. major amastigotes infecting mice intraperitoneal macrophages. The percentage of infected macrophages with five or more amastigotes was determined using a BD Pathway 855 high resolution fluorescence bioimager system. The Z-factor is 0.69 indicates that the quality of the assay is excellent. CTZ, clotrimazol; C1, C2, C3, metal controls (1.0 μM); ◆, infected cells treated with complex 5; □, infected untreated cells; ▲, infected cells treated with 5μM amphotericin B.

At this point, a comparison with previously reported metal complexes is significant: RuCl2(CTZ)2, first described by us in 1993, is perhaps the most efficacious metal complex known against T. cruzi in vitro, displaying a 10-fold enhancement of the activity of free CTZ and no toxicity toward normal Vero cells;15a, b unfortunately, this high in vitro activity did not translate to in vivo studies, mainly due to the low water solubility of the drug. Now we have disclosed a new family of Ru-CTZ compounds specifically designed to improve the biological properties, through a modulation of the solubility and other physicochemical features, from which 5 emerges as the most outstanding representative. As noted above, under the conditions of our experiments, this non-toxic complex 5 enhances the activity of CTZ by a factor of 58 against T. cruzi, which represents almost a 6-fold increase with reference to RuCl2(CTZ)215a, b. The molecular environments envisaged for the new complexes herein described indeed convey a higher water solubility with respect to the 4-coordinate species RuCl2(CTZ)2, which is highly insoluble.15a, b Nevertheless, the data for compounds 1-8 (Table 4, Experimental Section) indicate that although water solubility is an important parameter to consider in order to reach high biological activity, other factors must also be playing significant roles, as no clear correlations emerge between anti-T. cruzi activity and solubility alone.

Table 4.

Solubility of complexes 1-8 in water.

| Compound | mg/ml | μM |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.24 | 143 |

| 2 | Insoluble | Insoluble |

| 3 | 0.06 | 90 |

| 4 | Insoluble | Insoluble |

| 5 | 0.05 | 75 |

| 6 | 0.98 | 909 |

| 7 | 1.63 | 2000 |

| 8 | 0.33 | 435 |

A direct comparison with metal-based drugs reported for the treatment of L. major10-13 is not evident because of the differences in the formulations and structures of the compounds, as well as in the experimental conditions used to perform the biological tests. Nevertheless, complex 5 is, to our knowledge, the only reported metal complex displaying low nanomolar lethal doses (LD50 = 15 nM) against the promastigote form and high inhibition activity on the proliferation of intracellular amastigotes (IC70 = 29 nM) of L. major, the causative agent of leishmaniasis. Due to the highly promising results obtained for this novel family of Ru-CTZ compounds in our in vitro studies, they appear as excellent candidates for further drug development; to that end, relevant mechanistic studies and in vivo tests in experimental animals are currently in progress.

CONCLUSION

We have synthesized eight new complexes (1-8) combining clotrimazole with different ruthenium-containing fragments, and characterized them by a variety of physical methods including the crystal structures of the four organometallic RuII-CTZ compounds 5-8. The activity of all the new compounds has been evaluated against promastigotes of L. major and epimastigotes of T. cruzi, and compared to that of CTZ, a well known anti fungal agent with moderate antiparasitic activity. In most cases, the synergy caused by the complexation of CTZ to the metal results in an enhancement of the activity, with [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CTZ)] (5) as the most significant case. Complex 5 increases the activity of CTZ by factors of 110 and 58 against L. major and T. cruzi, respectively, without any signs of toxicity to normal human cells. In a high-content imaging assay (HCIA) on L. major infected intraperitoneal mice macrophages, complex 5 showed significant inhibition on the proliferation of intracellular amastigotes (IC70 = 29 nM), while Complex 8 displayed some effect at a higher concentration (IC40 = 1 μM). Therefore, these new compounds represent excellent leads for further development of possible effective treatments for leishmaniasis and Chagas’ disease.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis

All manipulations were performed under dry nitrogen using Schlenk techniques. Solvents (analytical grade, Aldrich) were dried and degassed prior to use by means of an Innovative Technology solvent purification unit; ruthenium trichloride hydrate (Pressure Chemicals Inc.), clotrimazole and other reagents (Aldrich) were used as received. [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2]240, [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(en)][BF4]41, [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(acac)]42, cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)429a, and Na[trans-RuIIICl4(DMSO)2]29b were prepared according to published procedures. FT-IR spectra were measured on a Thermoelectron NICOLET 380 FT-IR spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained using an AVANCE Bruker 400 instrument; chemical shifts are relative to residual proton or carbon signals in the deuterated solvents. The purity of the samples used for biological studies (≥ 95%) was determined by elemental analysis, performed by Atlantic Microlab, Norcross, Georgia.

cis,fac-[RuIICl2(DMSO)3(CTZ)] (1)

A solution of cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)4] (289 mg, 0.60 mmol) in dry methanol (10 ml) was stirred at 50 °C until complete dissolution. CTZ (205 mg, 0.60 mmol) was then added and the resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The pale yellow solid that precipitated was filtered off, washed with water, ethanol and ether and dried under vacuum. 75% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) 8.51 (s, H2 from CTZ), 7.83 (s, H4 from CTZ), 7.45 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, H9 from CTZ), 7.36 (m, H8, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.30 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.6 Hz, H7 from CTZ), 7.15 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 7.08 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, H6 from CTZ), 6.83 (s, H5 from CTZ), 3.50 (s, 6H from DMSO), 3.40 (s, 6H from DMSO), 3.21 (s, 6H from DMSO). IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3149 (m–w), 3006 (m–w) ν(C–H from Ar), 2919 (m–w) ν(C–H), 1629 (w), 1491(m□w), 1430 (m–s), 1399 (m) ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar), 1091 (s) ν(S-O), 421 (m) ν(Ru-S) . Anal. calcd for C28H35N2Cl3S3O3Ru: C 43.16, H 4.70, N 3.73. Found: C 43.50, H 4.64, N 3.68.

cis,cis,trans-[RuIICl2(DMSO)2(CTZ)2](2)

A solution of cis-[RuIICl2(DMSO)4] (289 mg, 0.60 mmol) in dry methanol (10 ml) was stirred at 50 °C until complete dissolution. CTZ (410 mg, 1.20 mmol) was then added and the resulting mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature. The solution was filtered, concentrated to half volume and left to crystallize. Yellow-orange crystals were formed after 4 days, filtered off and washed with ether. 70% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) 8.34 (s, H2 from CTZ), 7.64 (s, H4 from CTZ), 7.38 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, H9 from CTZ), 7.33 (m, H8, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.20 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, H7 from CTZ), 7.08 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, H6 from CTZ), 6.77 (s, H5 from CTZ), 3.14 (s, 12H from DMSO). IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3133 (m–w), 3063 (m– w), 3016 (m-w), ν(C–H from Ar); 2919 (m–w) ν(C–H); 1629 (w), 1492(m□w), 1445 (m–s), ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar); 1090 (s), ν(S-O); 421 (m) ν(Ru-S) Anal. calcd for C48H46N4Cl4S2O2Ru: C 56.04, H 4.81, N 5.33. Found: C 55.70, H 4.59, N 5.39.

Na[RuIIICl4(DMSO)(CTZ)] (3)

A solution of Na[trans-RuIIICl4(DMSO)2] (107.4 mg, 0.25 mmol) in methanol (10 ml) was stirred at 50 °C to complete dissolution. CTZ (88 mg, 0.25 mmol) was then added and the resulting mixture was stirred for 13 h at r.t. The solvent was removed under vacuum and distilled water was added to the dried residue and stirred for 15 min. The product was extracted with 3×10 ml of dichloromethane, dried over NaSO4 and the solvent was then evaporated to dryness to yield the final compound. 80% yield. IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3145 (m–w), 3053 (m–w), 3016 (m-w), ν(C–H from Ar); 2964 (m–w), ν(C–H); 1445 (m–s), ν(C=N from Ar); 1492 (m□w), ν(C=C from Ar); 1090 (s), ν(S-O); 425 (m), ν(Ru-S). Anal. calcd for C24H23N2Cl5SONaRu•2MeOH: C 41.5, H 4.16, N 3.7. Found: C 42.2, H 3.98, N 3.91.

Na[trans-RuIIICl4(CTZ)2] (4)

A solution of Na[trans-Ru Cl4(DMSO)2] (100.0 mg, 0.24 mmol) in dry methanol (6 ml) was stirred at 50°C until complete dissolution. CTZ (245 mg, 0.71 mmol) was then added and the resulting mixture was stirred for 13 h at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum and a yellow solid appeared that was redissolved in warm methanol, filtered, washed with diethyl ether and evaporated to dryness. 80% yield. IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3148 (m–w), 3057 (m–w), 3028 (m-w), ν(C–H from Ar); 2921 (m–w) ν(C–H); 1445 (m–s), ν(C=N from Ar); 1490(m□w) (C=C from Ar); 1078 (s), ν(S-O). Anal. calcd for C44H34N4Cl6NaRu•2MeOH: C 54.18, H 4.16, N 5.49. Found: C 54.50, H 4.29, N 5.52.

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CTZ)] (5)

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2]2 (201 mg, 0.3 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (30 ml). CTZ (228 mg, 0.7 mmol) was then added and the resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. An orange precipitate starts appearing after 1 h. The solvent was reduced to 4 ml under vacuum and precipitation was completed by addition of diethyl ether (30 ml). The orange solid was filtered, washed with diethyl ether and dried under vacuum. 83 % yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.86 (s, H2 from CTZ), 7.47 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, H9 from CTZ), 7.40 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.5 Hz, H8 from CTZ), 7.37 (m, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.31 (dd, J =7.8, 1.2 Hz, H7 from CTZ), 7.28 (s, H4 from CTZ), 7.13 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 7.03 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, H6 from CTZ), 6.83 (s, H5 from CTZ), 5.32 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H from p-cy), 5.14 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H from p-cy), 2.87 (hept, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H from p-cy), 2.11 (s, 3H from pcy), 1.21 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H from p-cy). IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3144 (m–w), 3060 (m–w) ν(C–H from Ar); 2968 (m–w), ν(C–H); 1530 (w), 1492(m□w), 1447 (m–s), 1432 (m) ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar). Anal. calcd for C32H31N2Cl3Ru: C 59.04, H 4.80, N 4.30. Found: C 58.75, H 4.87, N 4.28. Crystals of 1 suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained by slow evaporation of a hexane□dichloromethane solution.

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)(bipy)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (6)

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl2]2 (208.5 mg, 0.341 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (30 ml). A solution of AgBF4 (265.8 mg, 1.365 mmol) also in acetone (3 ml) was added, and the mixture was stirred protected from light at room temperature for 4 h. The orange solution was filtered to remove solid AgCl, left for 48 h at □20 °C and filtered again. 2,2’-bipyridine (106.4 mg, 0.681 mmol) was added and the reaction was left to proceed for 4 h at room temperature. CTZ (235.4 mg, 0.683 mmol) was then added and the resulting reddish-brown solution was vigorously stirred for 7 h at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, the resulting brownish solid was washed twice with hexane (2 × 30 ml), filtered and dried under vacuum. 75% yield. 1H NMR (Me2CO-d6) δ (ppm) 9.87 (d, J=5.7 Hz, 2H from bipy), 8.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H from bipy), 8.40 (td, J = 7.9, 1.4 Hz, 2H from bipy), 7.85 (m, 2H from bipy), 7.50 (m, H7, H9 from CTZ), 7.38 (m, H8, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.31 (m, H4 from CTZ), 7.25 (m, H2 from CTZ), 7.16 (m, H5 from CTZ), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, H6 from CTZ), 6.89 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 6.67 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H from p-cy), 6.34 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H from p-cy), 2.70 (hept, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H from p-cy), 2.19 (s, 3H from p-cy), 1.02 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H from p-cy). IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3128 (m–w), 3090 (m), ν(C–H from Ar); 2970 (m), 2877 (m–w), ν(C–H); 1606 (m), 1495(m), 1447 (m□s), 1431 (m), ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar). %. Anal. calcd for C42H39N4ClB2F8Ru•2H2O: C 53.33, H 4.58, N 5.92. Found: C 53.72, H 4.35, N 5.97.

A metathetical reaction of [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(bipy)(CTZ)][BF4]2 with a two-fold excess of picric acid in methanol solution at room temperature resulted in the formation of yellow-greenish crystals of [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(bipy)(CTZ)][C6H2N3O7]2 (6’) suitable for X-ray crystallography.

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)(en)(CTZ)][BF4]2 (7)

AgBF4 (118.4 mg, 0.608 mmol) was added to a solution of [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(en)][BF4] (226.7 mg, 0.543 mmol) in acetone (30 ml), and the mixture protected from light was stirred for 6 h at room temperature. The resulting solution was double filtered, evaporated to dryness and the product was extracted with a dichloromethane- acetone solvent mixture (5/1 v/v). CTZ (188.8 mg, 0.548 mmol) was then added and the resulting pale yellow solution was vigorously stirred for 4 h at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum and a pale yellow solid was obtained. The product was washed with hexane, filtered and dried under vacuum.

A solution of this product in dichloromethane (30 ml) was washed with distilled water (2 × 5 ml) to remove unreacted [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(en)][BF4], then dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness to yield a pale yellow solid that was washed with diethyl ether and dried under vacuum. 40% yield. 1H NMR (Me2CO-d6) δ (ppm) 8.368 (s, H2 from CTZ), 7.557 (m, H4, H8, H9 from CTZ), 7.444 (m, H7, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.326 (m, H5 from CTZ), 7.226 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 7.165 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.1 Hz, H6 from CTZ), 6.078 (s, br, 2H), 5.92 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 5.87 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 4.307 (s, br, 2H), 2.703 (m, 2H), 2.63 (hept, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.319 (m, 2H), 2.239 (s, 3H), 1.21 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H). 40%. IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3320 (m), 3279 (m), ν(N–H); 3172 (m–w), 3075 (m–w), ν(C–H from Ar); 2967 (m–w), 2869 (m–w), ν(C–H); 1599 (m), 1493(m), 1447 (m–s), ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar). Anal. calcd for C34H39N4ClB2F8Ru•Et2O: C 51.40, H 5.56, N 6.31. Found: C 51.26, H 5.22, N 6.69. Crystals of 7 suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained by slow evaporation of an acetone-d6 solution.

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)(acac)(CTZ)][BF4] (8)

[RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(acac)] (180 mg, 0.243 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (20 ml) and a solution of AgBF4 (129 mg 0.26 mmol) in acetone (3 ml) was added. The mixture was stirred protected from light at room temperature for 3 h. Then, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum and dichloromethane (30 mL) was added. AgCl and the slight excess of AgBF4 were filtered off to give a clear dark orange solution. CTZ (84.1 mg, 0.244 mmol) was then added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The yellow solution formed was concentrated and the product was precipitated as a yellow powder by addition of hexane (30 ml). Unreacted [RuII(η6-p-cymene)Cl(acac)] was removed by re-dissolving the product in dichloromethane and washing with distilled water (2 × 5 ml). The dichloromethane fraction was dried over Na2SO4 and the solvent was evaporated to dryness to yield [RuII(η6-p-cymene)(acac)(CTZ)][BF4] as a yellow solid. 70 % yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ (ppm) 7.43 (m, H8, H9 from CTZ), 7.36 (m, H2, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, H18 from CTZ), 7.31 (m, H7 from CTZ), 7.24 (m, H4 from CTZ), 7.04 (m, H10, H14, H15, H19 from CTZ), 6.94 (m, H6, H5 from CTZ), 5.64 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H from pcy), 5.48 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H from p-cy), 4.99 (s, 1H from acac), 2.71 (hept, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H from p-cy), 2.11 (s, 3H from p-cy), 1.77 (s, 6H from acac), 1.25 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H from p-cy). IR (selected bands, cm–1): 3178 (w), 3158 (m–w), 3060 (w), ν(C–H from Ar); 2967 (m–w), 2872 (m–w), ν(C–H); 1705 (m□s), ν(C=O); 1566 (s), 1516 (m), 1491 (m–s), 1432 (m), ν(C=N and/or C=C from Ar). Anal. calcd for C37H38N2ClO2BF4Ru•½H2O: C 57.34, H 5.07, N 3.61. Found: C 57.45, H 5.08, N 3.60. Crystals of 8 suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained by slow evaporation of a hexane□dichloromethane solution.

X-ray structure determinations

X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker Apex II diffractometer. Crystal data, data collection and refinement parameters are summarized in Table 3. CIF files have been deposited with Cambridge Crsytallographic Data Centre (CCDC). CCDC 861976 - 861979 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The structures were solved using direct methods and standard difference map techniques, and were refined by full-matrix least-squares procedures on F2 with SHELXTL (Version 6.10).43,44

Trypanosomatid cultures

Trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi Y strain were obtained from infected BALB/c mice by cardiac puncture 4 days following the intraperitoneal infection with 105 parasites. The procedure was performed minimizing the distress and pain for the animals, following the NIH guidance and animal protocol approved by UTEP's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Cell-derived trypomastigotes were initially obtained by infecting human osteoblast cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) as previously described.45,46 To maintain the trypomastigote virulence, a maximum of nine in vitro passages (infections) were performed. The epimastigote forms of T. cruzi (Y strain) were grown in liver infusion-tryptose (LIT) medium.47 Mammalian cell-derived trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi (Y strain) were obtained from infected LLC-MK2 cell (American Type Culture Collection-ATCC, Manassas, Virginia) monolayers as described.45 Promastigote forms of L. major strain Friedlin clone V1 were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI) supplemented with hemin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) inactivated at 56°C for 30 min.48

Culture of mammalian cells

Human osteoblast (ATCC # HTB-99) (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% inactivated FBS, along with 1% of 10,000 units/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin, in 0.9% sodium chloride. Cell cultures were regularly tested for Mycoplasma by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).49

Evaluation of the toxicity on mammalian cell lines and anti-trypanosomal activity — Alamar Blue assay

The toxicity to human osteoblasts and epimastigotes of T. cruzi Y strain was determined using Alamar Blue; the assay was performed as described before.45

Luciferase assay - Leishmania major

The anti-parasitic activity of the Ru-CTZ derivatives was determined using L. major strain Friedlin clone V1 expressing firefly luciferase. The drugs (stock solutions in DMSO) were tested in a concentration range from 7.5 μM to 58.5 nM, and 1 μl per well was added (1% DMSO final concentration) to 96-well microplates using an Eppendorf epMotion 5070 automated pipetting system. Promastigotes (106/well) were added, and parasite survival was assessed by luciferase activity with the substrate 5′-fluoroluciferin (ONE-Glo Luciferase Assay System, Promega) after 96-h incubation at 28°C, using a luminometer (Luminoskan, Thermo). The bioluminescent intensity was a direct measure of the survival of parasites. The assay was performed in triplicate in three independent experiments; lethal doses (LD50) were determined for each drug.

In vitro evaluation of complexes 5 and 8 by high-content imaging assay (HCIA) - infectivity experiments

To mimic the in vivo infection, mice intraperitoneal macrophages were placed in a microplate and infected with amastigotes of L. major strain Friedlin clone V1, followed by treatment with the compounds. Previous to infecting the macrophages, L. major promastigotes were washed and re-suspended at a density of 1-5 × 107 cells per 0.5 ml in 4% C5- mouse serum in macrophage media and incubated for 30 min at RT (without agitation). At a density of 1 × 106, the macrophages were seeded in a 96-well flat-bottom microplate for 30 min prior to infection. The infection of the macrophage cells was performed for 24 h at 36°C 5% CO2, at a ratio of 10 parasites per macrophage, in triplicate. The cells were subsequently washed twice with DMEM (with antibiotic without FBS) and incubated with the drugs. Several drug concentrations (937 nM to 29.25 nM) were assayed. The cells were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde) and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (1.25:100) and DAPI (1:1000), the number of infected cells and amastigotes were determined by HCIA using a BD Pathway 855 high resolution fluorescence bioimager system (BD biosciences).50 Filter sets appropriate for the excitation and emission spectra of Alexa Fluor 488 and DAPI (Sigma Aldrich) were selected. Images from nine contiguous image fields (3×3 montage) were acquired per well with a 20× (0.75 numerical aperture, NA) objective. For optimal segmentation and counting of parasites associated with host cells, the BDAttoVision™v1.6.2 Sub Object analysis was applied. Subsequently, the infection index was calculated based on the mean of these triplicate values, by multiplying the percentage of infected cells by the constraint used in the HCIA assay, which was of 5 parasites per macrophage. The infection index is thus directly proportional to the % of infected cells reported in Fig. 5. The constraints employed of 5 or more parasites per macrophage were used to calculate a z-factor (statistical effect size) of 0.69, which indicates that we have an excellent and reliable assay.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance (p-value) of the cytotoxicity of the compounds to the promastigote and epimastigote forms of the parasites and human cells, as well as in the proliferation of the intracellular amastigotes (HCIA assay) was calculated using the General Linear Mixed Model Analysis. This analysis was used to test the linear effect of the logarithm of dose on the logit transformation of the Percent Survival. Each IC50 value was obtained as the exponent of the negative ratio of the y-intercept and the slope of the fitted regression line (SAS Software, Version 9.2). To directly calculate the SE the Non-Linear Mixed Model was used. This method requires the raw data as the number of parasites that survive (r) and the total number (n) of parasites. In our HCIA and Luciferase assays we measured the fluorescence or relative luminescence, respectively, from where the percentage of survival and/or amastigotes per macrophages (not the specific number of parasites) was calculated. The graphs for display were attained using Graph Pad Prism 5 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, California).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the NIH through Grant # 5SC1GM089558-02 (to R.A. S.-D.) is gratefully acknowledged. R.A.M.'s laboratory was supported by grant # 2S06GM00812-37 from the NIH/MBRS/NIGMS/SCORE Program and Border Biomedical Research Center (BBRC) pilot research grant #5G12RR008124. The Biomolecule Analysis Core Facility (BACF), High- throughput Core Facility (HTSCF) and Statistical Consulting Laboratory (SCL) at the BBRC, UTEP, are supported by NIH/NCRR grant # 5G12RR008124. The National Science Foundation (CHE-0619638) is thanked for the acquisition of an X ray diffractometer for Columbia University. T.C. was supported by the RISE Undergraduate Research Program Grant #5R25GM069621-06. A. A. thanks the Venezuelan Academy of Sciences for a Graduate Fellowship. We thank Professor Stephen Beverley of Washington University School of Medicine for kindly providing the L. major strain Friedlin clone V1 expressing luciferase. We thank Ms. V. Medialdea (Brooklyn College) for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- acac

acetylacetonate

- bipy

bipyridine

- CL

cutaneous leishmaniasis

- CTZ

clotrimazole

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- en

ethylenediamine

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HCIA

high-content imaging assay

- Hmtpo

5-methyl-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a] pyrimidin-7(4H)-one

- KTZ

ketoconazole

- L

Leishmania

- LIT

liver infusion-tryptose

- Lm

Leishmania major

- MCL

mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

- NAMI

new anti-tumour metastasis inhibitor

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SBI

sterol biosynthesis inhibitor

- T

Trypanosoma

- VL

visceral leishmaniasis

References

- 1.a den Boer M, Argaw D, Jannin J, Alvar J. Leishmaniasis impact and treatment access. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2011;17(10):1471–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b WHO Control of leishmaniases. Report of a WHO expert committee. WHO Tech. Rep. Ser. 2010;949:1–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a WHO Control of Chagas disease. World Health Organization Technical Reports Series. 2002;905:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Barrett MP, Burchmore RJS, Stich A, Lazzari JO, Frasch AC, Cazzulo JJ, Krishna S. The trypanosomiases. The Lancet. 2003;362(9394):1469–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14694-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dias JC, Silveira AC, Schofield CJ. The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97(5):603–612. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Franco-Paredes C, Ault SK, Periago MR. The Neglected Tropical Diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: A Review of Disease Burden and Distribution and a Roadmap for Control and Elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(9):e300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kirchhoff LV. Epidemiology of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). Adv Parasitol. 2011;75:1–18. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385863-4.00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ Disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(4):655–681. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schmunis GA. Epidemiology of Chagas disease in non-endemic countries: the role of international migration. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(Suppl 1):75–85. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Diaz JH. Chagas disease in the United States: a cause for concern in Louisiana? J. La. State. Med. Soc. 2007;159(1):21–3. 25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft SL, Barrett MP, Urbina JA. Chemotherapy of trypanosomiases and leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21(11):508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selzer PM. Antiparasitic and Antibacterial Drug Discovery. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponte-Sucre A, Diaz E, Padron-Nieves M. Drug Resistance in Leishmania Parasites: Consequences, Molecular Mechanisms and Possible Treatments. Springer; Vienna: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polonio T, Efferth T. Leishmaniasis: drug resistance and natural products (review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2008;22(3):277–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Urbina JA. Specific chemotherapy of Chagas disease: Relevance, current limitations and new approaches. Acta Tropica. 2010;115(1-2):55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Urbina JA. New Insights in Chagas’ Disease Treatment. Drugs of the Future. 2010;5(35):409–419. [Google Scholar]; c Urbina JA. Ergosterol biosynthesis and drug development for Chagas disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(Suppl. 1):311–318. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000900041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urbina JA, Payares G, Molina J, Sanoja C, Liendo A, Lazardi K, Piras MM, Piras R, Perez N, Wincker P, Ryley JF. Cure of Short- and Long-Term Experimental Chagas’ Disease Using D0870. Science. 1996;273(5277):969–971. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Sánchez-Delgado RA, Anzellotti A, Suárez L. Metal complexes as chemotherapeutic agents against tropical diseases: malaria, trypanosiomiasis and leishmaniasis. In: Siegel H, Siegel A, editors. Met. Ions Biol. Syst. Vol. 41. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 2004. pp. 379–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sánchez-Delgado RA, Anzellotti A. Metal Complexes as Chemotherapeutic Agents Against Tropical Diseases: Trypanosomiasis, Malaria and Leishmaniasis. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2004;4(1):23–30. doi: 10.2174/1389557043487493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarro M, Gabbiani C, Messori L, Gambino D. Metal-based drugs for malaria, trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis: recent achievements and perspectives. Drug Discovery Today. 2010;15(23-24):1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fricker SP, Mosi RM, Cameron BR, Baird I, Zhu Y, Anastassov V, Cox J, Doyle PS, Hansell E, Lau G, Langille J, Olsen M, Qin L, Skerlj R, Wong RSY, Santucci Z, McKerrow JH. Metal compounds for the treatment of parasitic diseases. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:1839–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Sullivan MC. The battle against trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis: Metal-based and natural product inhibitors of trypanothione reductase. Curr. Med. Chem.: Anti-Infect. Agents. 2005;4:355–378. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alessio E. Bioinorganic Medicinal Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Sánchez-Delgado RA, Lazardi K, Rincon L, Urbina JA, Hubert AJ, Noels AN. Toward a novel metal-based chemotherapy against tropical diseases. 1. Enhancement of the efficacy of clotrimazole against Trypanosoma cruzi by complexation to ruthenium in RuCl2(clotrimazole)2. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36(14):2041–2043. doi: 10.1021/jm00066a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sánchez-Delgado RA, Navarro M, Lazardi K, Atencio R, Capparelli M, Vargas F, Urbina JA, Bouillez A, Noels AF, Masi D. Toward a novel metal based chemotherapy against tropical diseases 4. Synthesis and characterization of new metal-clotrimazole complexes and evaluation of their activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1998;275-276:528–540. [Google Scholar]; c Navarro M, Lehmann T, Cisneros-Fajardo EJ, Fuentes A, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Silva P, Urbina JA. Toward a novel metal-based chemotherapy against tropical diseases.: Part 5. Synthesis and characterization of new Ru(II) and Ru(III) clotrimazole and ketoconazole complexes and evaluation of their activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Polyhedron. 2000;19(22-23):2319–2325. doi: 10.1021/ic0103087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Navarro M, Cisneros-Fajardo EJ, Lehmann T, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Atencio R, Silva P, Lira R, Urbina JA. Toward a Novel Metal-Based Chemotherapy against Tropical Diseases. 6. Synthesis and Characterization of New Copper(II) and Gold(I) Clotrimazole and Ketoconazole Complexes and Evaluation of Their Activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40(27):6879–6884. doi: 10.1021/ic0103087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a Martínez A, Rajapakse C, Naoulou B, Kopkalli Y, Davenport L, Sánchez-Delgado R. The mechanism of antimalarial action of the ruthenium(II)-chloroquine complex [RuCl2(CQ)]2. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13(5):703–712. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rajapakse CSK, Martínez A, Naoulou B, Jarzecki AA, Suárez L, Deregnaucourt C, Sinou V, Schrével J, Musi E, Ambrosini G, Schwartz GK, Sánchez-Delgado RA. Synthesis, Characterization, and in vitro Antimalarial and Antitumor Activity of New Ruthenium(II) Complexes of Chloroquine. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48(3):1122–1131. doi: 10.1021/ic802220w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Martínez A, Rajapakse C, Jalloh D, Dautriche C, Sánchez-Delgado RA. The antimalarial activity of Ru-chloroquine complexes against resistant Plasmodium falciparum is related to lipophilicity, basicity, and heme aggregation inhibition ability near water-octanol interfaces. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009;14(6):863–871. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Otero L, Vieites M, Boiani L, Denicola A, Rigol C, Opazo L, Olea-Azar C, Maya JD, Morello A, Krauth-Siegel RL, Piro OE, Castellano E, González M, Gambino D, Cerecetto H. Novel Antitrypanosomal Agents Based on Palladium Nitrofurylthiosemicarbazone Complexes: DNA and Redox Metabolism as Potential Therapeutic Targets‚. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49(11):3322–3331. doi: 10.1021/jm0512241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vieites M, Otero L, Santos D, Olea-Azar C, Norambuena E, Aguirre G, Cerecetto H, González M, Kemmerling U, Morello A, Diego Maya J, Gambino D. Platinum-based complexes of bioactive 3-(5-nitrofuryl)acroleine thiosemicarbazones showing anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vieites M, Otero L, Santos D, Toloza J, Figueroa R, Norambuena E, Olea-Azar C, Aguirre G, Cerecetto H, González M, Morello A, Maya JD, Garat B, Gambino D. Platinum(II) metal complexes as potential anti-Trypanosoma cruzi agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102(5-6):1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Demoro B, Sarniguet C, Sánchez-Delgado R, Rossi M, Liebowitz D, Caruso F, Olea-Azar C, Moreno V, Medeiros A, Comini MA, Otero L, Gambino D. New organoruthenium complexes with bioactive thiosemicarbazones as co-ligands: potential anti-trypanosomal agents. Dalton Transactions. 2012;41:1534–1543. doi: 10.1039/c1dt11519g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Merlino A, Otero L, Gambino D, Laura CE. 2011;46:2639–2651. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vieites M, Smircich P, Parajon-Costa B, Rodriguez J, Galaz V, Olea-Azar C, Otero L, Aguirre G, Cerecetto H, Gonzalez M, Gomez-Barrio A, Garat B, Gambino D. Potent in vitro anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of pyridine-2-thiol N-oxide metal complexes having an inhibitory effect on parasite-specific fumarate reductase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:723–735. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Benitez J, Guggeri L, Tomaz I, Pessoa JC, Moreno V, Lorenzo J, Aviles FX, Garat B, Gambino D. A novel vanadyl complex with a polypyridyl DNA intercalator as ligand: A potential anti-protozoa and anti-tumor agent. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:1386–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rodrigues C, Batista AA, Ellena J, Castellano EE, Benitez D, Cerecetto H, Gonzalez M, Teixeira LR, Beraldo H. Coordination of nitro-thiosemicarbazones to ruthenium(II) as a strategy for anti-trypanosomal activity improvement. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;45:2847–2853. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnici CL, Araujo MH, Oliveira HS, Moreira DRM, Pereira VRA, Souza M. d. A., Brelaz d. C. M. C. A., Leite ACL. Ruthenium complexes endowed with potent anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity: Synthesis, biological characterization and structure-activity relationships. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5038–5043. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maia P. I. d. S., Fernandes A. G. d. A., Silva JJN, Andricopulo AD, Lemos SS, Lang ES, Abram U, Deflon VM. Dithiocarbazate complexes with the [M(PPh3)]2+ (M = Pd or Pt) moiety Synthesis, Characterization and anti-Tripanosoma Cruzi activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demoro B, Caruso F, Rossi M, Benitez D, Gonzalez M, Cerecetto H, Parajon-Costa B, Castiglioni J, Galizzi M, Docampo R, Otero L, Gambino D. Risedronate metal complexes potentially active against Chagas disease. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:1252–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caballero AB, Marin C, Rodriguez-Dieguez A, Ramirez-Macias I, Barea E, Sanchez-Moreno M, Salas JM. In vitro and in vivo antiparasital activity against Trypanosoma cruzi of three novel 5-methyl-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7(4H)-one-based complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batista D. d. G. J., da SPB, Stivanin L, Lachter DR, Silva RS, Felcman J, Louro SRW, Teixeira LR, Soeiro M. d. N. C. Co(II), Mn(II) and Cu(II) complexes of fluoroquinolones: Synthesis, spectroscopical studies and biological evaluation against Trypanosoma cruzi. Polyhedron. 2011;30:1718–1725. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro M, Hernandez C, Colmenares I, Hernandez P, Fernandez M, Sierraalta A, Marchan E. Synthesis and characterization of [Au(dppz)2]Cl3. DNA interaction studies and biological activity against Leishmania (L) mexicana. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101(1):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarro M, Cisneros-Fajardo EJ, Marchan E. New silver polypyridyl complexes: synthesis, characterization, and biological activity on Leishmania mexicana. Arzneim. Forsch. 2006;56:600–604. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baiocco P, Ilari A, Ceci P, Orsini S, Gramiccia M, Di MT, Colotti G. Inhibitory Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Trypanothione Reductase Activity and Leishmania infantum Proliferation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:230–233. doi: 10.1021/ml1002629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everson d. S. L., Teixeira d. S. P., Jr., Maciel EN, Nunes RK, Eger I, Steindel M, Rebelo RA. In vitro antiprotozoal evaluation of zinc and copper complexes based on sulfonamides containing 8-aminoquinoline ligands. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2010;7:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 29.a Evans IP, Spencer A, Wilkinson G. Dichlorotetrakis(dimethyl sulphoxide)ruthenium(II) and its use as a source material for some new ruthenium(II) complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1973;(2):204–209. [Google Scholar]; b Alessio E, Balducci G, Calligaris M, Costa G, Attia WM, Mestroni G. Synthesis, molecular structure, and chemical behavior of hydrogen trans-bis(dimethyl sulfoxide)tetrachlororuthenate(III) and mer-trichlorotris(dimethyl sulfoxide)ruthenium(III): the first fully characterized chloride-dimethyl sulfoxide-ruthenium(III) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30(4):609–618. [Google Scholar]

- 30.a Henn M, Alessio E, Mestroni G, Calligaris M, Attia WM. Ruthenium(II)-dimethyl sulfoxide complexes with nitrogen ligands: synthesis, characterization and solution chemistry. The crystal structures of cis,fac-RuCl2(DMSO)3(NH3) and trans,cis,cis-RuCl2(DMSO)2(NH3)2.H2O. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1991;187(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]; b Alessio E, Calligaris M, Iwamoto M, Marzilli LG. Orientation and Restricted Rotation of Lopsided Aromatic Ligands. Octahedral Complexes Derived from cis-RuCl2(Me2SO)4. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35(9):2538–2545. doi: 10.1021/ic9509793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sens C, Rodríguez M, Romero I, Llobet A. Synthesis, Structure, spectroscopy, Photochemical, Redox and Catalytic Properties of New Ru(II) Isomeric Complexes Containing Dimethylsulfoxide, Chloro and the Dinucleating bis-2-pyridylpyrazole ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42(6):2049–2048. doi: 10.1021/ic026114o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwamoto M, Alessio E, Marzilli LG. Observation of an Unusual Molecular Switching Device. The Position of One 1,2-Dimethylimidazole Switched “On” or “Off” the Rotation of the Other 1,2-Dimethylimidazole in cis,cis,cis-RuIICl2(Me2SO)2(1,2-dimethylimidazole)2. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35(8):2384–2389. doi: 10.1021/ic951063z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marzilli LG, Iwamoto M, Alessio E, Hansen L, Calligaris M. The Rare Head-to-Head Conformation of Untethered Lopsided Ligands Discovered in Both Solution and Solid States of 1,5,6-Trimethylbenzimidazole Re(V) and Ru(II) Complexes. JACS. 1994;116(2):815–816. [Google Scholar]

- 34.a Alessio E, Balducci G, Lutman A, Mestroni G, Calligaris M, Attia WM. Synthesis and characterization of two new classes of ruthenium(III)-sulfoxide complexes with nitrogen donor ligands (L): Na[trans-RuCl4(R2SO)(L)] and mer, cis-RuCl3(R2SO)(R2SO)(L). The crystal structure of Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)(NH3)] . 2DMSO, Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)(Im)].H2O, Me2CO (Im = imidazole) and mer, cis-RuCl3(DMSO)(DMSO)(NH3). Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1993;203(2):205–217. [Google Scholar]; b Velders AH, Bergamo A, Alessio E, Zangrando E, Haasnoot JG, Casarsa C, Cocchietto M, Zorzet S, Sava G. Synthesis and Chemical-Pharmacological Characterization of the Antimetastatic NAMI-A-Type Ru(III) Complexes (Hdmtp)[trans-RuCl4(dmso-S)(dmtp)], (Na)[trans-RuCl4(dmso-S)(dmtp)], and [mer-RuCl3(H2O)(dmso-S)(dmtp)] (dmtp = 5,7-Dimethyl[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine). J. Med. Chem. 2004;47(5):1110–1121. doi: 10.1021/jm030984d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Anderson CM, Herman A, Rochon FD. Synthesis and characterization of ionic Ru(III) complexes containing dimethylsulfoxide and dinitrogen heterocyclic ligands. Polyhedron. 2007;26(14):3661–3668. [Google Scholar]

- 35.a Cebrián-Losantos B, Reisner E, Kowol CR, Roller A, Shova S, Arion VB, Keppler BK. Synthesis and Reactivity of the Aquation Product of the Antitumor Complex trans-[RuIIICl4(indazole)2]-. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47(14):6513–6523. doi: 10.1021/ic800506g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peti W, Pieper T, Sommer M, Keppler BK, Giester G. Synthesis of Tumor-Inhibiting Complex Salts Containing the Anion trans-Tetrachlorobis(indazole)ruthenate(III) and Crystal Structure of the Tetraphenylphosphonium Salt. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999;1999(9):1551–1555. [Google Scholar]; c Lipponer KG, Vogel E, Keppler BK. Synthesis, Characterization and Solution Chemistry of trans-Indazoliumtetrachlorobis(Indazole)Ruthenate(III), a New Anticancer Ruthenium Complex. IR, UV, NMR, HPLC Investigations and Antitumor Activity. Crystal Structures of trans-1-Methyl-Indazoliumtetrachlorobis-(1-Methylindazole)Ruthenate(III) and its Hydrolysis Product trans-Monoaquatrichlorobis-(1-Methylindazole)-Ruthenate(III). Met.-Based Drugs. 1996;3(5):243–260. doi: 10.1155/MBD.1996.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris RE, Aird RE, del Socorro Murdoch P, Chen H, Cummings J, Hughes ND, Parsons S, Parkin A, Boyd G, Jodrell DI, Sadler PJ. Inhibition of Cancer Cell Growth by Ruthenium(II) Arene Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44(22):3616–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm010051m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freedman DA, Kruger S, Roosa C, Wymer C. Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity of [Ru(bpy)(CH3CN)3(NO2)]PF6, a Synthon for [Ru(bpy)(L3)NO2] Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45(23):9558–9568. doi: 10.1021/ic061039t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernández R, Melchart M, Habtemariam A, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. Use of Chelating Ligands to Tune the Reactive Site of Half-Sandwich Ruthenium(II)–Arene Anticancer Complexes. Chemistry – A European Journal. 2004;10(20):5173–5179. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vock CA, Scolaro C, Phillips AD, Scopelliti R, Sava G, Dyson PJ. ynthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Ruthenium(II)h6-Arene Imidazole Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49(18):5552–5561. doi: 10.1021/jm060495o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett MA, Huang TN, Matheson TW, Smith AK. Inorg. Synth. 1982;21:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crabtree RH, J. Pearman A. Arene-ruthenium complexes containing nitrogen donor ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;141(3):325–330. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmona D, Ferrer J, Oro LA, Apreda MC, Foces-Foces C, Cano FH, Elguero J, Jimeno ML. Synthesis, X-ray structure, and nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C) studies of ruthenium(II) complexes containing pyrazolyl ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1990;(4):1463–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL, An Integrated System for Solving, Refining and Displaying Crystal Structures from Diffraction Data. University of Göttingen: Göttingen; Federal Republic of Germany: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A. 2008;64(Pt 1):112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lara D, Feng Y, Bader J, Savage PB, Maldonado RA. Anti-trypanosomatid activity of ceraginins. J. Parasitol. 2010;96(3):638–642. doi: 10.1645/GE-2329.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrews NW, Colli W. Adhesion and interiorization of Trypanosoma cruzi in mammalian cells. Journal of Protozoology. 1982;29(2):264–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1982.tb04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camargo EP. Growth And Differentiation In Trypanosoma Cruzi. I. Origin Of Metacyclic Trypanosomes In Liquid Media. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1964;12:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thalhofer CJ, Graff JW, Love-Homan L, Hickerson SM, Craft N, Beverley SM, Wilson ME. In vivo imaging of transgenic Leishmania parasites in a live host. J Vis Exp. 2010;(41):Pii. doi: 10.3791/1980. 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uphoff CC, Drexler HG. Detection of mycoplasma contaminations. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:13–23. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nohara LL, Lema C, Bader JO, Aguilera RJ, Almeida IC. High-content imaging for automated determination of host-cell infection rate by the intracellular parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol Int. 2010;59(4):565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang JH, Chung TDY, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]