Abstract

The time tradeoff (TTO) method is often used to derive Quality-Adjusted Life Year health state valuations. An important problem with this method is that results have been found to be responsive to the procedure used to elicit preferences. In particular, fixing the duration in the health state to be valued and inferring the duration in full health that renders an individual indifferent, causes valuations to be higher than when the duration in full health is fixed and the duration in the health state to be valued is elicited. This paper presents a new test of procedural invariance for a broad range of time horizons, while using a choice-based design and adjusting for discounting. As one of the known problems with the conventional procedure is the violation of constant proportional tradeoffs (CPTO), we also investigate CPTO for the alternative TTO procedure. Our findings concerning procedural invariance are rather supportive for the TTO procedure. We find no violations of procedural invariance except for the shortest gauge duration. The results for CPTO are more troublesome: TTO scores depend on gauge duration, reinforcing the evidence reported when using the conventional procedure.

Keywords: Procedural invariance, Constant proportional tradeoffs, Discounting, Time tradeoff method

Introduction

Health economic evaluations to a large extent rely on the time tradeoff (TTO) method to measure health state utilities. This method measures utilities by letting individuals trade off lifetime against health status. A major problem in employing the TTO method for health state valuations is the finding of violations of procedural invariance, that is, the scores attached to a health state depend heavily on the procedure used to obtain that score [1–3]. In general terms, the TTO method elicits the point of indifference between two streams of health, typically a shorter time span in full health and a longer period in an impaired health state. When a respondent is indifferent between n years in full health and x years in health state β, the value of β is obtained by dividing n by x. Obviously, for health states better than death, one may obtain the value of β either through fixing the period in β (conventional procedure) or that in full health (alternative procedure). In theory, both should yield the same valuation, but several studies found the conventional procedure to result in significantly higher scores than the alternative procedure [1, 2]. Since it is unclear which of these procedures, if any, captures underlying preferences, these findings are problematic.

One potential determinant of violations of procedural invariance is the elicitation design. In particular, one can use a matching design or a choice-based design. Many TTO elicitations employ a matching design to determine indifferences, in which a respondent has to indicate the number of years in full health that renders him indifferent to a given number of years in an impaired health state [4–8]. Choice-based designs [9], though, are better embedded in economic theory [10] and may lead to fewer inconsistencies [11]. Furthermore, choice-based designs naturally provide a more neutral situation, suggesting a smaller impact of loss aversion and other biases [2] and, hence, procedural invariance may be more likely to hold in that case.

This paper addresses the problem of procedural invariance by performing a more rigorous test than previous studies using a fully choice-based, computerized, design and a broad range of time horizons (denoted “gauge durations” henceforth). The advantage of a computerized questionnaire is the facilitation of chaining of the answers, enabling fast elicitation of choice-based indifferences and efficient testing of procedural invariance. The advantage of using a broad range of gauge durations is that we can test whether the earlier observed behavioral discrepancies between short and long-time horizons [4, 12, 13] can be extended to the domain of procedural invariance. In addition, we investigate the role of discounting when the results are not in accordance with theory, i.e., when both procedures do not result in similar TTO scores.

Another interesting question concerns the validity of the constant proportional tradeoffs (CPTO) property using the alternative elicitation procedure. There is a considerable amount of evidence about CPTO for the conventional procedure [14, 15], but not so much for the alternative procedure. The two studies on this topic rejected CPTO [2, 14], but both used a more limited range of gauge durations than the current study. Using a broad range of gauge durations is especially important in this context, since the available evidence seems to indicate that findings of violations of CPTO may be related to the gauge durations used [14]. The use of multiple durations allows us to perform a new and more elaborate test of CPTO for the alternative procedure in this paper, covering gauge durations between 3 and 46 years. Furthermore, we investigate the role of discounting by adjusting for utility of life duration curvature.

Terminology

Let us start by introducing the terminology used throughout this paper. h = (h j,…,h n) denotes a health profile where ht is the health state in period t = j,…,n, with n denoting the final period under consideration. A constant health profile h = (h j = α,…,h n = α) is indicated as (α, n). Further, v(h t) is a value function that represents the individual’s preferences over health quality and δ(t) denotes the corresponding weight attached to the value in this period.

The Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) model is a widely used model in health economic evaluations. A general version of this model can be written as:

|

1 |

The TTO method infers health state utilities by asking subjects to consider two constant health profiles (β, n β) and (γ, n γ), with, in general, γ a better health state than β and n β > n γ. When an individual is indifferent between these two profiles, according to (1), we obtain the following equality:

|

2 |

Often no discounting is assumed so that Eq. 2 can be simplified to n β * v(β) = n γ * v(γ), which means, after normalizing v(γ) to 1, that the utility of the health state is simply v(β) = n γ/n β. In this case, it does not matter whether preferences are elicited by fixing the duration in β and asking for n γ, or by fixing the duration in γ and asking for n β, as the ratio in theory will be the same for both. Although most TTO studies perform the conventional procedure to measure health state utilities [9, 16], the alternative procedure should, in principle, give the same results according to this model.

Unfortunately, the QALY model may not be a good descriptive model, caused by phenomena such as loss aversion, scale compatibility, and maximum endurable time [17–19]. If these or other distorting factors would differ between the two procedures, resulting in differences between them, discounting may become relevant in explaining the differences [1]. Therefore, we first have to measure δ(t), since a test of these differences depends on the real size of the utility differences, which is only available if one adjusts for discounting.

Background

All studies that thus far have tested procedural invariance between the conventional and alternative TTO procedures indeed rejected it or found mixed evidence. In particular, they found systematically higher values for the alternative procedure for at least some of the included comparisons [1–3]. Discounting was not found to explain this dichotomy [1, 2], pointing toward other biases that should be taken into account. Adjusting for discounting did, however, reduce the differences between the elicited utilities.

Three published papers have studied procedural invariance so far. First, Bleichrodt et al. [2] asked five conventional TTO questions, with a gauge duration ranging between 13 and 38 years, and back pain as the impaired health state. The answers (i.e., number of years in full health that made respondents indifferent to the specified number of years with back pain) were used as gauge duration in the alternative procedure 2 weeks later, when the subjects had to come back. For example, if a subject in the first session had expressed indifference between 13 years with back pain and 10 years in full health, in the second session he had to indicate how many years with back pain was of equal value as 10 years in full health. Procedural invariance would then require the subject to elicit 13 years again here. Bleichrodt et al. [2] showed that discounting should not distort the results in this case, since the involved periods in case of procedural invariance are identical.

Bleichrodt et al. [2] used a choice-based design to elicit TTO scores. They used a questionnaire, in which the respondents were confronted with a list of choices between a number of years with back pain and a number of years in full health (see Appendix 1). The subjects indicated in this test per choice whether they preferred the number of years with back pain or the number of years in full health. The conventional procedure resulted in higher TTO scores for the three shortest gauge durations, whereas no significant differences were present for the two longest gauge durations. Bleichrodt et al. [2] attributed the difference for the shorter durations to loss aversion, which tends to be more influential for shorter durations [20]. This finding is consistent with lexicographic preferences (or short-term indifferent subjects) for short durations that were found in earlier studies [12, 21].

Secondly, Spencer [3] used four conventional and two alternative questions. The questions for the conventional procedure all had a gauge duration of 10 years, but in different health states, which were described in terms of the five EuroQol dimensions. The questions for the alternative procedure had a gauge duration of 2 years in two different imperfect health states. Indifferences were reached by letting subjects choose and varying the response mode until the subject was indifferent between the two alternatives. Spencer did not use answers to one procedure as input in the other procedure, however, and, hence, the results were distorted by discounting, but not adjusted for. She found mixed results. For one health state, the conventional procedure yielded a higher TTO score than the alternative procedure, but for the other, there was no significant difference. Maximum endurable time may, however, have played a role in the latter finding, as this question used a very poor health state.

Third, Attema and Brouwer [1] performed two conventional and two alternative TTO exercises, with back pain and full health as the health states. They used fixed gauge durations for all questions, but they did adjust for discounting by means of a discounting elicitation method [22]. The gauge durations for the conventional procedure were 14 and 27 years, and 10 and 22 years for the alternative procedure. An open ended matching design was used to elicit indifferences. Higher TTO scores for the conventional procedure were found for both questions, also after adjusting for discounting.

The present study was designed to address the issue of procedural invariance, attempting to combine the best elements of previous studies and to add an improved elicitation method. That is, we used multiple gauge durations and a choice-based design, and our experiment was in principle designed in such a way that the equality of both procedures was not distorted by discounting. In that sense, it was comparable to the study by Bleichrodt et al. [2] in a number of respects, but also attempted to further refine this. In accordance with their study, we took the answers of the subjects to the questions in the conventional procedure and used them as gauge durations in the alternative procedure. Their study also used a choice-based design to elicit TTO scores, although it differed from ours in the following way. In contrast to [2], our design gave choices one by one on a computer screen, so that subjects faced only one choice at a time and could not see the other choices during the making of one particular choice. Another difference with the preceding studies is that we considered a broader range of time horizons, between 3 and 46 years, allowing us to test procedural invariance for short, intermediate, and long durations.

As discounting should theoretically not matter in our design, we could have simply compared the unadjusted TTO scores for the two procedures. However, we also investigated the results for the adjusted TTO scores, since discounting does influence the results when procedural invariance does not hold, for example, due to loss aversion [1]. Any difference between the two methods is then influenced by discounting, so that adjusting for this provides a better insight into the differences in utility terms. We elicited the utility function for life duration by means of a risk-free method [22] for this purpose, and employed the adjustment procedure of Attema and Brouwer [8] to adjust the TTO results for the elicited discounting results.

Finally, the QALY model without discounting implies the presence of CPTO, i.e., the ratio n

γ/n

β is constant and independent of the gauge duration. Similarly, for the generalized QALY model, the ratio  is constant. There is, however, some empirical evidence rejecting CPTO for the conventional procedure [14, 15]. The broad range of durations in this study allowed us to test whether the same findings occur for the alternative procedure, both in its traditional form and in a more generalized form (i.e., adjusted for discounting).

is constant. There is, however, some empirical evidence rejecting CPTO for the conventional procedure [14, 15]. The broad range of durations in this study allowed us to test whether the same findings occur for the alternative procedure, both in its traditional form and in a more generalized form (i.e., adjusted for discounting).

Experiment

Subjects

The subject pool consisted of 83 Business Administration undergraduate students who participated for course credits. They were recruited by means of a research participation system, i.e., an electronic device that allows students to choose one or more experiments out of a variety of different experiments. These experiments contained short descriptions and the students could enroll for the experiment they preferred. Except for the course credits, no additional incentives were provided.

Procedure

The experiment was administered on computers in the laboratory at Erasmus University Rotterdam. The experimental sessions were run by one of the authors with four subjects at a time, and the subjects were separated by partitions. The sessions lasted 30 min on average and covered more questions than relevant for the current study. Both the two TTO procedures and the discounting part used a bisection procedure, which let subject make a series of choices, while “zooming in” to an indifference value. Practice questions and repeat choices were included to test understanding of the subjects. The repeat questions consisted of a repetition of the first question of a sequence at the end of that sequence. In case the choice in the repeat question disagreed with the choice in the original question, the sequence was elicited anew and the indifference of the second sequence was used in the analysis.

Stimuli TTO elicitation

We chose the health states “regular back pain” (β) and “full health” (γ) throughout the experiment. The health state “regular back pain” is a common health state and subjects were likely to know people suffering from it [1]. We described the health state using the domains contained in the EuroQol 5D questionnaire. We therefore indicated what regular back pain meant for daily functioning in terms of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). The descriptions were printed on cards and handed to the participants (see Appendix 2). It was made clear to the subjects that full health meant they were able to function perfectly on all five dimensions, irrespective of their age.

We used five different time horizons in the TTO elicitation process: 3, 10, 15, 31, and 46 years. These numbers were chosen so as to minimize the potential influence of a proportional heuristic [23]. We used short, intermediate, and long time horizons, enabling a more complete test of procedural invariance. The different time horizons were asked in a randomized order. Although the results for both the conventional and the alternative procedure were elicited during the same experimental session, it was unlikely that subjects used their memory in the alternative procedure to give the answers consistent with the gauge durations in the conventional procedure. First, the test discussed in this paper was combined with several other tests, so that subjects had to perform a number of tasks in-between the conventional and alternative procedures, distracting their attention from the questions and answers in the first (conventional) procedure. Second, since the design was choice-based, the subjects never the saw the exact indifference value, which was used as gauge duration in the alternative procedure.

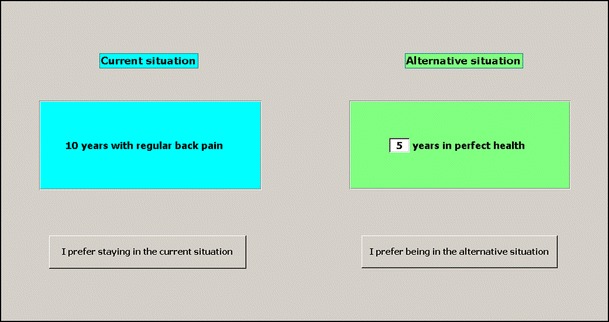

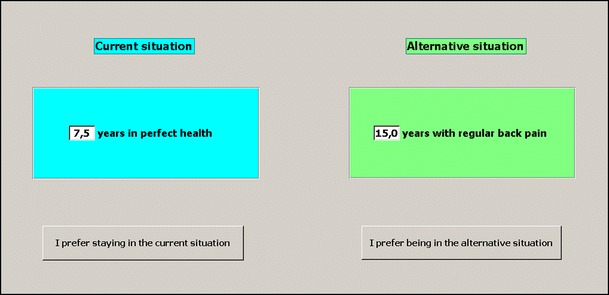

The two TTO procedures were designed to differ only on those elements necessary to perform our test. Appendix 3 graphically illustrates this by presenting screen shots of two questions that a subject may have faced during the experiment, one for the conventional procedure (Fig. 4) and one for the alternative procedure (Fig. 5). Table 1 further clarifies these procedures by presenting the stimuli, an imaginary subject would face for a particular choice pattern in case of the gauge duration n β = 10 years. The table shows that an indifference value of n γ = 7.5 was stored for this subject. Hence, this value was subsequently used as the gauge duration in the alternative procedure. Procedural invariance would then require the resulting elicited indifference value of nβ to be (approximately) 10 again. Our imaginary subject violates procedural invariance to a small extent, however, resulting in an estimated indifference value of 10.75.

Fig. 4.

Screen shot of a question in the conventional TTO procedure

Fig. 5.

Screen shot of a question in the alternative TTO procedure

Table 1.

Illustration of the choice procedures

| Conventional procedure | Alternative procedure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of years with back pain (current situation, option A) | Number of years in full health (alternative situation, option B) | Option chosen | Number of years in full health (current situation, option A) | Number of years with back pain (alternative situation, option B) | Option chosen |

| 10 | 10 | B | 7.5 | 7.5 | A |

| 10 | 5 | A | 7.5 | 15 | B |

| 10 | 8 | B | 7.5 | 11.2 | B |

| 10 | 6 | A | 7.5 | 9.4 | A |

| 10 | 7 | A | 7.5 | 10.3 | A |

| 7.5 | 10.75 | ||||

Stimuli discounting elicitation

The considered time horizon was set equal to 50 years, because this was a plausible amount for our sample of students. Then, the discounting task [22] basically first elicited the point where the respondent attached equal weight to the first x years as to the following 50-x years; in other words, the point where the total utility of the first x years was equal to the total utility of the following 50-x years. We elicited this point presenting two health scenarios to the subjects. In one scenario, he or she was in a good health state at first, but, after some time x, would move to a worse health state for 50-x years. In the other scenario, the subject was in the worse health state at first and at time x moved to the better health state for 50-x years. The elicited value of x was the value that made the subject indifferent between the two scenarios. For instance, if due to discounting a person attached as much weight to the first 10 years as he did to the remaining 40 years, this defined x 0.5.

Subsequently, using this first estimate, it was possible to derive x 0.125, x 0.25, x 0.75, and x 0.875 as well (i.e., the points where the first number of years received 12.5, 25 etc. percent of the weight and the other years the remaining weight). More details about the discounting elicitation task can be found in [24].

Analyses

We computed the unadjusted TTO scores for the conventional procedure in the usual way by dividing the elicited indifference value by the fixed number of years with back pain. For the alternative procedure the fixed number of years in full health was divided by the elicited number of years with back pain. The results for the two procedures were compared in several ways. One comparison involved a set of t tests comparing the mean responses in the alternative procedure to the gauge durations in the conventional procedure. According to procedural invariance, these responses should equal the gauge durations used in the conventional procedure. In addition, we compared the TTO scores for the two procedures by the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed ranks test.1

Results

The data of 7 subjects were removed because they did not indicate preferring more life years to fewer life years.2 As a result, the data of 76 subjects were included in the analysis (mean age 20.5 (SD = 2.8), 42 (55%) men).

Procedural invariance

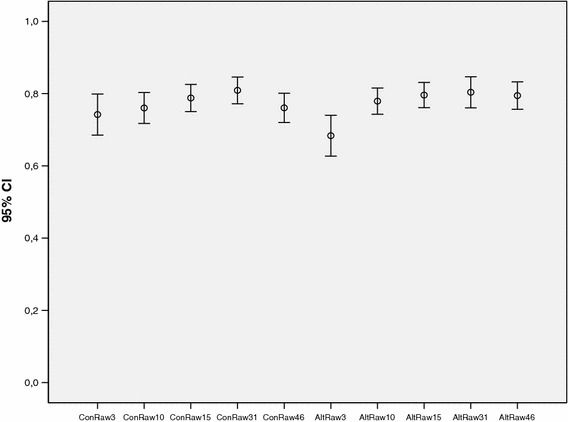

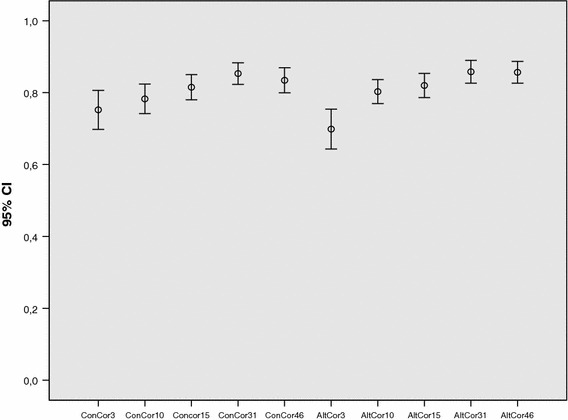

Figures 1 and 2 show the means and 95% confidence intervals of the unadjusted and adjusted TTO scores, respectively, for all gauge durations and for both the conventional and the alternative procedure. These results indicate, first, that TTO scores are similar for both procedures and, second, that there is a positive correlation between gauge duration and TTO scores.

Fig. 1.

Mean unadjusted TTO scores (including 95% confidence intervals). Results generated by the conventional procedure are abbreviated by “Con”; those from the alternative procedure by “Alt”. The numbers indicate the corresponding gauge durations

Fig. 2.

Mean adjusted TTO scores (including 95% confidence intervals)

Tables 2 and 3 present summary statistics for the raw answers and the corresponding TTO scores, as well as the results of the hypothesis tests related to procedural invariance. Interestingly, except for the 3-year time horizon, we could not fully reject the hypothesis of procedural invariance when using the t test. The Wilcoxon signed ranks test gave similar results, except that the difference for the gauge duration of 46 years became significant as well.3 When we adjusted for discounting and compared the adjusted TTO scores, the conclusions did not change. The high and significant Pearson correlation coefficients between the estimates for the conventional and the alternative procedures confirmed the findings in the previous paragraph that the two procedures generated similar results.

Table 2.

Summary statistics unadjusted answers and TTO scores

| Gauge duration in conventional procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 10 | 15 | 31 | 46 | |

| TTO score conventional procedure | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.25) | 0.76 (0.19) | 0.79 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.16) | 0.76 (0.18) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 0.83 (0.62–0.97) | 0.75 (0.65–0.89) | 0.83 (0.68–0.90) | 0.87 (0.74–0.94) | 0.84 (0.64–0.90) |

| TTO score alternative procedure | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.68 (0.25) | 0.78 (0.16) | 0.80 (0.15) | 0.80 (0.19) | 0.79 (0.17) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 0.76 (0.45–0.85) | 0.83 (0.64–0.94) | 0.84 (0.70–0.94) | 0.86 (0.72–0.94) | 0.85 (0.73–0.92) |

| Pearson ρ of conventional and alternative proc. (all P < 0.01) | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.65 |

| Wilcoxon test of conventional TTO = alternative TTO (P) | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.02 |

| Answer in alternative procedure | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.61 (2.13) | 9.93 (2.52) | 14.93 (2.06) | 32.57 (9.80) | 45.00 (10.52) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 3.05 (2.85–3.80) | 9.85 (8.9–10.6) | 14.80 (14.4–15.8) | 30.55 (28.7–32.1) | 44.90 (41.6–47.8) |

| T test of Mean answer alt. proc. = X (P values) | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 0.41 |

Table 3.

Summary statistics adjusted TTO scores

| Gauge duration in conventional procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 10 | 15 | 31 | 46 | |

| TTO score conventional procedure | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.75 (0.24) | 0.78 (0.18) | 0.82 (0.15) | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.83 (0.15) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 0.83 (0.62–0.97) | 0.81 (0.72–0.90) | 0.87 (0.74–0.92) | 0.90 (0.78–0.94) | 0.90 (0.76–0.94) |

| TTO score alternative procedure | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.70 (0.24) | 0.80 (0.15) | 0.82 (0.15) | 0.86 (0.14) | 0.86 (0.13) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | 0.77 (0.50–0.92) | 0.83 (0.71–0.93) | 0.85 (0.76–0.94) | 0.93 (0.79–0.95) | 0.91 (0.80–0.95) |

| Pearson correlation coefficient (all P < 0.01) | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.69 |

| Wilcoxon test of conventional TTO = alternative TTO (P) | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.04 |

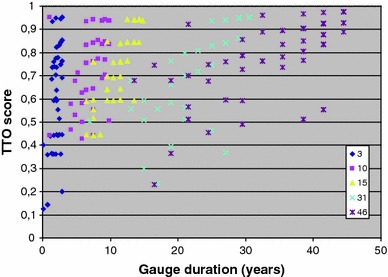

CPTO for the alternative procedure

Next, we investigated CPTO for the alternative procedure. Figures 1 and 2 already indicated that TTO scores were not independent from gauge duration. The Friedman test of equal TTO scores for all five durations in the alternative procedure confirmed this; it was rejected for both unadjusted and adjusted TTO scores (P < 0.01). The unadjusted TTO scores increased (at a decreasing rate) with duration until 31 years and decreased slightly between 31 and 46 years, i.e., we found a predominantly positive correlation, as shown in more detail in Fig. 3. The same finding held for adjusted scores, although the gap between unadjusted and adjusted scores increased with duration, and the variance was reduced throughout when we adjusted for discounting. Notice the considerable amount of heterogeneity between subjects. This is hard to explain, considering the homogeneity of the sample. One possibility is that young people, having little or no experience with the presented health state, have different interpretations of the seriousness of this scenario. Another possibility is that subjects have difficulty imagining small life expectancies, especially when faced with the shortest gauge durations.

Fig. 3.

Relation between gauge duration and unadjusted TTO scores (alternative procedure). The gauge duration was the answer given by the subject to the corresponding question in the conventional procedure. Because these answers obviously differed between subjects, we use a scatter plot here

Discussion

Procedural invariance is an important topic in the area of TTO measurements. There are essentially two procedures that can be used to determine indifferences, i.e., varying the duration in full health or varying the duration in an impaired health state. It is unclear which of these two procedures is better, in the sense of better describing preferences of the respondents, and often relatively large differences are found between the two procedures. Therefore, research explaining these differences and inferring which procedure gives better estimates of true preferences seems warranted.

In this study, we found relatively modest differences between the two different procedures, which, to some extent, is a different result than the previous studies in this area. A logical explanation of this result would be that it is correlated with the use of longer gauge durations and a choice-based design. In particular, replacing a matching design by a choice-based design tends to decrease the impact of loss aversion considerably [2], only leaving a significant impact for short durations. This tendency was confirmed in another study, which, for the same subjects as in this study, found a significant difference between the conventional and alternative procedure while using a matching design [25]. We conjecture that a choice-based design introduces a more neutral scenario, causing subjects to focus more on tradeoffs; in matching designs, they may tend to give more attention to the amount of years given up (conventional procedure) or the deterioration in health (alternative procedure). However, the use of different samples and health states may also be a determinant of the different results.

While our findings are encouraging when considering procedural invariance, the property of CPTO was rejected in our study. This finding adds to the evidence against the QALY model, as our results are in line with previous results [2, 14]. Those studies also reported a positive correlation between gauge duration and TTO scores for the alternative procedure.

In our study, we were able to adjust for discounting to see whether this would reduce the observed violations. It is clear that adjusting for discounting does not reduce the problem, but instead results in even stronger violations of CPTO. This implies that when differences occur in terms of proportions traded off, these are not mainly driven by discounting, but rather by utility differences. An explanation for the upward trend in TTO scores in the alternative procedure is that, for longer durations, subjects do not require relatively as many extra life years to compensate for the decreased health status as for shorter durations. It may be that the subjective life expectancy (SLE) plays an important role here. Recent studies found evidence for an impact of SLE on TTO valuations [26, 27]. In particular, people tend to take their SLE as their reference point and relate the time frame of the TTO questions to that reference point. Most of the subjects in our study had an SLE that exceeded the time frames in the TTO questions and, hence, all these situations involved losses as seen from this reference point. However, these losses were smaller for the longer gauge durations, causing subjects to demand fewer extra life years in return for a worse health status.

Although we put substantial effort into decreasing the impact of remembrance on the results in the alternative procedure, it cannot be ruled out that this has influenced our findings. Also, the fact that for the gauge duration of 3 years, we found a violation of procedural invariance in the direction predicted by loss aversion indicates differently. Another limitation of the present study is that we always started with the conventional procedure. This may have created an ordering effect. Therefore, future research is needed to replicate this test without the possible influence of remembrance, while randomizing the order of the procedures to control for ordering. Nevertheless, the findings regarding procedural invariance are promising and suggest that a choice-based design is less susceptible to the option that is varied (i.e., the number of years in the impaired health state or the number of years in full health). Moreover, the reduction in variance after adjusting for discounting, which was also found in another study [24] for the conventional procedure, emphasizes the usefulness of this adjustment, especially when keeping in mind the large variation found in TTO studies [28]. Moreover, our sample only included university students and considered only one disease state (back pain), which may hamper generalization of our findings. For example, Dolan and Roberts [29] reported age and education to be correlated with health states values. On the other hand, de Wit et al. [30] did not find systematic differences between student samples and general population samples. Therefore, we recommend future research on this topic to investigate a sample representative of the general population and to include more than one health state.

Contrary to most previous findings, this paper has provided some evidence in favor of procedural invariance. When using a choice-based design and intermediate and long-gauge durations, the conventional and alternative procedure did not produce significantly different results. These findings are to some extent in agreement with those of Bleichrodt and Pinto [20], who found less evidence of an influence of loss aversion for longer gauge durations than for shorter gauge durations, although they considered relatively long durations (between 13 and 38 years). The role of choice-based designs in reducing deviations from procedural invariance deserves more investigation. The findings regarding CPTO, on the other hand, highlight the poor empirical validity of the QALY model in its current form. We conclude therefore that, especially given the popularity of the TTO and the QALY model (also in relation to health care decision-making), more research is warranted. In particular, more research is needed that develops and tests criteria to assist determining the preferable procedure for the performance of TTOs. In addition, the relation between proportions traded off and gauge durations deserves further attention. This includes qualifying and quantifying the several influential factors, such as discounting, loss aversion, and SLE, and how they change for different time horizons.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix 1

See Table 4.

Table 4.

Answer sheet of Bleichrodt et al. [2]

| Your current situation is 1 | You can change to situation 2 | Decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Years with back pain | Years in full health | I remain in 1 | I am indifferent between 1 and 2 | I change to 2 |

| 1 | 13 | 13 | |||

| 2 | 13 | 0 | |||

| 3 | 13 | 11 | |||

| 4 | 13 | 2 | |||

| 5 | 13 | 9 | |||

| 6 | 13 | 4 | |||

| 7 | 13 | 7 | |||

| 8 | 13 | 5 | |||

Appendix 2: Health state descriptions (translated)

Card 1: regular back pain

You have regular back pain. This has the following consequences for your functioning in daily life:

You have no problems in walking about.

You have no problems to wash or dress yourself.

You have some problems with your usual activities.

You have moderate pain or other discomfort.

You are not anxious or depressed.

Card 2: full health

You have no complaints and are in full health. This has the following consequences for your functioning in daily life:

You have no problems in walking about.

You have no problems to wash or dress yourself.

You have no problems with your usual activities.

You have no pain or other discomfort.

You are not anxious or depressed.

Appendix 3: Screen shots of questions in the conventional and alternative TTO procedures (translated)

Footnotes

The TTO scores were skewed to the left for all time horizons, rejecting a normal distribution, so we do not report paired t tests.

This number is comparable to that of Bleichrodt et al. [2].

The latter finding may be related to the fact that there was less precision possible in eliciting preferences for the longer gauge durations, since the number of iterations was fixed, while the number of years between the subsequent steps was obviously larger. As a result, it was not always possible to return a value of exactly 46, causing many subjects to elicit a value somewhat below 46.

References

- 1.Attema AE, Brouwer WBF. Can we fix it? Yes we can! But what? A new test of procedural invariance in TTO-measurement. Health Econ. 2008;17:877–885. doi: 10.1002/hec.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleichrodt H, Pinto JL, Abellán-Perpinán JM. A consistency test of the time trade-off. J. Health Econ. 2003;22:1037–1052. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer A. The TTO method and procedural invariance. Health Econ. 2003;12:655–668. doi: 10.1002/hec.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stiggelbout AM, Kiebert GM, Kievit J, Leer JW, Habbema JD, De Haes JC. The “utility” of the time trade-off method in cancer patients: feasibility and proportional Trade-Off. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995;48:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00011-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleichrodt H, Johannesson M. Standard gamble, time trade-off and rating scale: experimental results on the ranking properties of QALYs. J. Health Econ. 1997;16:155–175. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(96)00509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleichrodt H, Johannesson M. The validity of QALYs: an empirical test of constant proportional tradeoff and utility independence. Med. Decis. Mak. 1997;17:21–32. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9701700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin AJ, Glasziou PP, Simes RJ, Lumley T. A comparison of standard gamble, time trade-off, and adjusted time trade-off scores. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2000;16:137–147. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300161124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attema AE, Brouwer WBF. The correction of TTO-scores for utility curvature using a risk-free utility elicitation method. J. Health Econ. 2009;28:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ. 1996;5:141–154. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199603)5:2<141::AID-HEC189>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolan P. The measurement of health-related quality of life for use in resource allocation decisions in health care. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. North Holland: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 1723–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bostic R, Herrnstein RJ, Luce RD. The effect on the preference-reversal phenomenon of using choice indifferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1990;13:193–212. doi: 10.1016/0167-2681(90)90086-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto JM, Eraker SA. A multiplicative model of the utility of survival duration and health quality. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1988;117:3–20. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.117.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeil BJ, Weichselbaum R, Pauker SG. Speech and survival: tradeoffs between quality and quantity of life in laryngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981;305:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198110223051704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attema AE, Brouwer WBF. On the (not so) constant proportional tradeoff in TTO. Qual. Life Res. 2010;19:489–497. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchiya A, Dolan P. The QALY model and individual preferences for health states and health profiles over time: a systematic review of the literature. Med. Decis. Mak. 2005;25:460–467. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudex C, Dolan P, Kind P, Thomas R, Williams A. Valuing health states: interviews with the general public. Eur. J. Public Health. 1997;7:441–448. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/7.4.441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleichrodt H. A new explanation for the difference between time trade-off utilities and standard gamble utilities. Health Econ. 2002;11:447–456. doi: 10.1002/hec.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stalmeier PFM, Chapman GB, de Boer AGEM, van Lanschot JJB. A fallacy of the multiplicative QALY model for low-quality weights in students and patients judging hypothetical health states. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2001;17:488–496. doi: 10.1017/S026646230110704X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland HJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Boyd NF, Till JE. Attitudes toward quality of survival. Med. Decis. Mak. 1982;2:299–309. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8200200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleichrodt H, Pinto JL. Loss aversion and scale compatibility in two-attribute trade-offs. J. Math. Psychol. 2002;46:315–337. doi: 10.1006/jmps.2001.1390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pliskin JS, Shepard D, Weinstein MC. Utility functions for life years and health status. Oper. Res. 1980;28:206–224. doi: 10.1287/opre.28.1.206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attema, A.E., Bleichrodt, H., Wakker, P.P.: Measuring discounting and QALYs more easily and reliably. Erasmus University Rotterdam. http://www.bmg.eur.nl/personal/attema/U_life_no_risk_2011.pdf (2011). Accessed 4 Mar 2011

- 23.Stalmeier PF, Bezembinder TG, Unic IJ. Proportional heuristics in time tradeoff and conjoint measurement. Med. Decis. Mak. 1996;16:36–44. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attema, A.E., Brouwer, W.B.F.: Constantly proving the opposite? A test of CPTO using a broad time horizon and correcting for discounting. Qual. Life Res. (2011). doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9917-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Attema, A.E., Brouwer, W.B.F.: In search of a preferred preference elicitation method: a test of the internal consistency of choice and matching procedures. Erasmus University Rotterdam. http://www.bmg.eur.nl/personal/attema/PrefRev_2010.pdf (2010). Accessed 5 July 2010

- 26.van Nooten FE, Koolman X, Brouwer WBF. The influence of subjective life expectancy on health state valuations using a 10 year TTO. Health Econ. 2009;18:549–558. doi: 10.1002/hec.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Nooten FE, Brouwer WBF. The influence of subjective expectations about length and quality of life on time trade-off answers. Health Econ. 2004;13:819–823. doi: 10.1002/hec.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnesen T, Trommald M. Are QALYs based on time trade-off comparable?–a systematic review of TTO methodologies. Health Econ. 2005;14:39–53. doi: 10.1002/hec.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolan P, Roberts J. To what extent can we explain time trade-off values from other information about respondents? Soc. Sci. Med. 2002;54:919–929. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Wit GA, Busschbach JJ, De Charro FT. Sensitivity and perspective in the valuation of health status: whose values count? Health Econ. 2000;9:109–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200003)9:2<109::AID-HEC503>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]