Abstract

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a life-threatening infection caused by Leishmania species. In addition to typical clinical findings as fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cachexia, VL is associated with autoimmune phenomena. To date, VL mimicking or exacerbating various autoimmune diseases have been described, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). Herein, we presented a patient with VL who had overlapping clinical features with SLE, AIH, as well as antimitochondrial antibody (AMA-M2) positive primary biliary cirrhosis.

Keywords: Leishmania, visceral leishmaniasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania species and has visceral, cutaneous, and mucocutaneous forms in humans. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar, a disseminated and potentially fatal form, is endemic in areas of the tropics, subtropics, and Southern Europe [1,2]. The disease can be observed sporadically at countries bordering Mediterranean basin, including Turkey [3].

Classic clinical features of VL include high fever, anorexia, hepatomegaly, marked splenomegaly, and pancytopenia due to severe involvement of reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs, particularly the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Laboratory tests usually show elevated inflammatory markers, marked eosinopenia, a relative lympho-monocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia with hypoalbuminemia, and occasionally evidence of liver damage with raised liver enzymes [1,2].

Diagnosis of leishmaniasis is based on demographic, clinical, and laboratory findings. Definite diagnosis requires demonstration of the parasite either histologically in relevant tissues or with Leishmania-specific immunologic tests [1]. However, diagnosis could be challenging in sporadic cases and often delayed, as the main clinical presentation is often identical to other infectious and non-infectious diseases. Furthermore, some of VL manifestations are associated with immune responses of the host to Leishmania that mimic autoimmune diseases like serum sickness [4].

Autoimmune phenomena are common in leishmaniasis which could be related to polyclonal B-cell activation, molecular mimicry between microbial and host antigens, and altered-reduced regulatory and suppressor T cell functions [4,5]. As a consequence of these disturbances, several autoantibodies appear in the sera of patients with VL, albeit, in most cases accompanying clinical manifestations are lacking [5]. On the other hand, there are several reports on concurrent or masquerading presentations with autoimmune diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and cryoglobulinemia in the literature [6-8]. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is also reported [9]. However, VL resembling AIH and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) overlap hepatitis has not been described before. Herein, we report a case of VL with clinical and laboratory features mimicking AIH, PBC overlap hepatitis, and SLE.

CASE RECORD

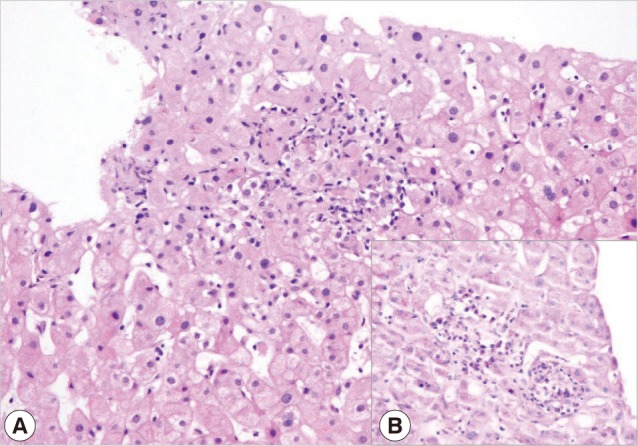

A 26-year-old female patient referred to the rheumatology department with complaints of anorexia, malaise, weight loss, joint swelling, and low grade fever. She was living in a Mediterranean region of Turkey. Her past history was notable for photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and possible thalassemia trait. On admission, her physical examination was significant for erythema and symmetrical arthritis at ankles, wrists, and hand joints. The spleen was palpated 10 cm below the costal margin, and the liver had a longitudinal size of 15 cm. Erythrocyst sedimentation rate (ESR) and C- reactive protein was 65 and 19.9 mg/L, respectively. Complete blood count revealed hemoglobin 10.2 gr/dl, mean corpuscular volume 69 fl, leukocyte 4,000/mm3, and platelet 157,000/mm3. Other pertinent laboratory data was as follows: creatinine 0.7 mg/dl (Normal=0.5-1.2), alanine aminotransferase 46 U/L (ALT, Normal<40), aspartate aminotransferase 51 U/L (AST, Normal<40), alkaline phosphatase 67 U/L (ALP, N=53-141), gama-glutamyl transferase 17 U/L (GGT, N=0-50), albumin 3.2 g/dl, globulin 6.9 g/dl, and lactate dehydrogenase 236 U/L (N=125-243). Her laboratory investigation was positive for anti-nuclear antibody immunofluorescence (ANA-IFA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), and Coombs tests on previous referral center. Repeated ANA was strongly positive as well as antimitochondrial (AMA-M2) antibodies and Coombs tests. Rheumatoid factor (RF) was 123 IU/ml (N<20). Liver kidney microsomal (anti-LKM), anti-cytosolic liver (LC-1), antisoluble liver/liver-pancreas (SLA/LP), ASMA, anti-ENA, ds-DNA tests were negative. Serum C3 and C4 were within normal limits. IgG was 5,810 mg/dl (N=751-1,560) with a polyclonal pattern. A liver biopsy was performed to rule out autoimmune hepatitis. Histological examination of the liver biopsy revealed robust plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltrations in the sinusoidal areas, and periductal and portal small granuloma formation. Histochemically, plasma cells, which were stained for Methyl Grün Pyronine (MGP), were found to act as a dominant feature among the inflammatory infiltrates in the liver. This finding also supported and raised the suspicion of autoimmune hepatitis-PBC overlap (Fig. 1A, B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Indirect cholestatic features with lobular confluent necrosis (H&E stain, ×200). (B) Plasma cells as a dominant component of inflammation in the liver (MGP, ×400)

Prednisone was started at a dose of 1 mg/kg under a presumptive diagnosis of SLE/AIH with a rapid clinical improvement on arthritis, fever, malaise and general condition, liver function tests, acute phase response, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Therefore, azathioprine 50 mg b.i.d. was added to the therapy with tapering steroid dose. A few weeks after the immunosuppression, her leukocyte and platelet counts began to fall gradually, reaching 1,000/mm3 and 14,000/mm3, respectively. Azathiopurine was discontinued. The patient was transferred to the infectious diseases department with the diagnosis of neutropenic fever. An empirical therapy with cefoperazone sulbactam was started. After 4 days, teicoplanin and fluconazole were added to the treatment because of urinary infection caused by enterococci and Candida albicans. Although, against this appropriate treatment, her condition got worse, fever continued, and neutropenia and thrombocytopenia persisted. A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed to rule out possible bone marrow pathology.

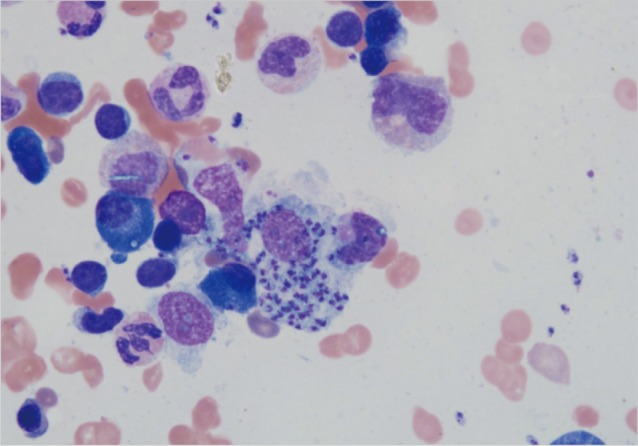

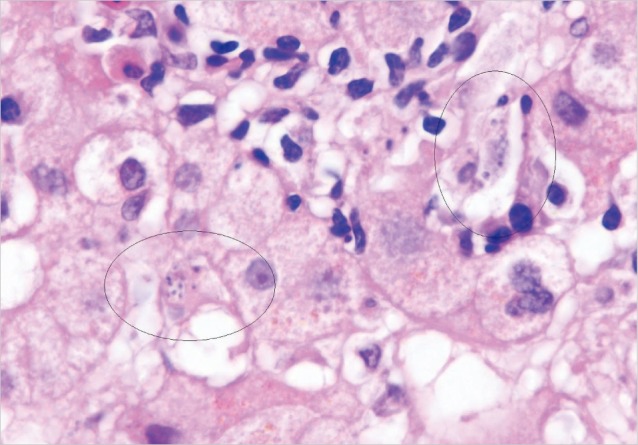

The bone marrow smears revealed macrophages with numerous Leishmania amastigotes (Fig. 2). The bone marrow biopsy also showed Leishmania parasites within macrophages. The amastigote tissue forms were seen when her liver biopsy was re-evaluated (Fig. 3). Leishmania IgG was found positive at a 1/1,280 titer in her serum specimen by indirect immunofluorescent assay. High dose (4 mg/kg/day) intravenous liposomal amphotericin B was given on days 1 to 5 and 10, 17, 24, 31, and 38 days [10]. Then, her fever resolved, and general conditions greatly improved with the exception of neutropenia. After a dose of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, her neutrophil count also reached to a normal level. No other complications were observed in the duration of the treatment.

Fig. 2.

A bone marrow smear showing macrophages containing numerous Leishmania amastigotes (May-Grunwald/Giemsa stain, ×100).

Fig. 3.

Clusters of leishmanias within the cytoplasm of Kupffer cells in the liver (H&E stain, ×1,000)

On her follow-up examination at 6 months after amphotericin therapy, she was in good clinical condition with free of any complaints and had normal blood counts, biochemical analyzes, and normal gammaglobulin levels. ASMA become negative, and ANA and AMA-M3 tests remained weak and strong positives, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease, which is transmitted to humans by sandflies in endemic areas. VL is considered endemic in tropical and subtropical regions (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil) in the world. However, in other countries, it is detected in a few cases. In Turkey, VL is seen mainly in the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Central Anatolia regions, and Leishmania infantum is the most responsible agent for the human diasese. Children were at a higher risk of infection, and only a few adult cases of VL were reported from Turkey [9,11-13].

Our patient was living in an endemic region. VL is a disseminated intracellular infection with a fatality rate of as high as 90%, unless treated. Classic clinical features include high fever, severe anorexia, and marked hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory tests frequently show pancytopenia, marked eosinopenia, a relative lympho-monocytosis and hypergammaglobulinemia with hypoalbuminemia, and occasionally evidence of liver damages with raised liver enzymes. The diagnosis is based on a combination of demographic, clinical, laboratory findings, and confirmation of the disease via demonstration of amastigote tissue forms of parasites or Leishmania-specific immunological tests [1,2]. VL remains asymptomatic or subclinical in many cases, or can follow an acute, subacute, or chronic course. Chronic VL results in delays in diagnosis due to subtle or atypical presentations [1].

Autoimmune phenomena are common in Leishmania infections. This might be due to a release of high amounts of self antigens as a result of tissue destruction caused by the parasite. Release of tissue antigens may stimulate the autoreactivity and autoantibody production. Another possible mechanism is altered host immune responses caused by Leishmania parasites. Both T and B cells are affected by VL [14]. VL causes polyclonal B cell activation independent of T cells through mitogen activation or stimulation of cytokines by other immune cells [4,5]. B cell hyperactivation results in severe hypergammaglobulinemia observed in VL. Finally, as demonstrated previously, there are some molecular mimicry between Leishmania antigens and host antigens such as ribosomal phosphoproteins expressed on parasites, causing cross-reactivity [5,14].

Reported autoimmune diseases that were mimicked or exacerbated by leishmaniasis are SLE, AIH, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and Ewan's syndrome [6-9,11,12]. All of them, particularly SLE and AIH have clinical and laboratory features undistinguishable from VL that makes confusion. Moreover, many autoantibodies are formed in VL, even disease specific ones, including RF, anticitrulline, ANA, ds-DNA, ASMA, anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Sm, anti-cardiolipin, and anti-platelet antibodies [4,5,14,15]. Positivity of one or more of these tests with vague clinical presentations may be misinterpreted as autoimmune disorders.

A correct diagnosis of VL was tricky in our patient because of presentation which was very similar to the autoimmune liver disease and SLE. Though the liver enzymes are frequently elevated in leishmaniasis, positive autoimmune laboratory tests and liver biopsy reported as consistent with AIH-PBC overlap led us to consider autoimmune overlap hepatitis and SLE as the cause. Rapid response to prednisone further supported AIH/SLE diagnosis. Hematological manifestations appeared later in the clinical course and that was thought as an azathioprine side-effect. However, discontinuation of this drug and escalating prednisone dose did not improve clinical pictures, and the patient was re-evaluated revealing VL diagnosis.

PBS or its serological marker AMA-M2 positivity has not been reported in patients with VL, to the best of our knowledge. Persistently high titers of AMA-M2 even 6 months after the appropriate treatment could be consistent with true diagnosis of PBS in our patient which might be concurrent with VL. However, re-biopsy was refused by the patient.

Leishmaniasis is characterized by multiple immunological abnormalities and protean clinical manifestations that may be misinterpreted as various autoimmune diseases. Moreover, early responses to immunosuppressives may masquerade clinical pictures of VL. Treatment of autoimmune diseases may worsen the disease and even cause a fatal outcome in VL patients. Therefore, in case of atypical presentations or treatment failure in autoimmune diseases, leishmaniasis should be considered and ruled out.

References

- 1.Magıll AJ. Leishmania species: visceral (kala-azar), cutaneus, and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, USA: Churchill Livingston; 2010. pp. 3463–3480. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ready PD. Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvão-Castro B, Sá Ferreira JA, Marzochi KF, Marzochi MC, Coutinho SG, Lambert PH. Polyclonal B cell activation, circulating immune complexes and autoimmunity in human american visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;56:58–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argov S, Jaffe CL, Krupp M, Slor H, Shoenfeld Y. Autoantibody production by patients infected with Leishmania. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:190–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arlet JB, Capron L, Pouchot J. Visceral leishmaniasis mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16:203–204. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181dfd26f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voulgari PV, Pappas GA, Liberopoulos EN, Elisaf M, Skopouli FN, Drosos AA. Visceral leishmaniasis resembling systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1348–1349. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.014480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casato M, de Rosa FG, Pucillo LP, Ilardi I, di Vico B, Zorzin LR, Sorgi ML, Fiaschetti P, Coviello R, Laganà B, Fiorilli M. Mixed cryoglobulinemia secondary to visceral leishmaniasis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2007–2011. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199909)42:9<2007::AID-ANR30>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalgic B, Dursun I, Akyol G. A case of visceral leishmaniasis misdiagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16:52–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bern C, Adler-Moore J, Berenguer J, Boelaert M, den Boer M, Davidson RN, Figueras C, Gradoni L, Kafetzis DA, Ritmeijer K, Rosenthal E, Royce C, Russo R, Sundar S, Alvar J. Liposomal amphotericin B for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:917–924. doi: 10.1086/507530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alioglu B, Avci Z, Ozyurek E, Ozbek N. Visceral leishmaniasis presented with Evans syndrome: A case report. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:1030–1031. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erduran E, Bahadir A, Gedik Y. Kala-azar associated with coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia in the patients coming from the endemic area of this disease and successful treatment of these patients with liposomal amphotericin B. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;22:349–355. doi: 10.1080/08880010590964110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yazici P, Yeniay L, Aydin U, Taşbakan M, Ozütemiz O, Yilmaz R. Visceral leishmaniasis as a rare cause of granulomatosis hepatitis: A case report. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2008;32:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakkas LI, Boulbou M, Kyriakou D, Makri I, Sinani C, Germenis A, Stathakis N. Immunological features of visceral leishmaniasis may mimic systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atta AM, Carvalho EM, Jerônimo SM, Sousa Atta ML. Serum markers of rheumatoid arthritis in visceral leishmaniasis: Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody. J Autoimmun. 2007;28:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]