Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the usefulness of PCR for diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among male patients with chronic recurrent prostatitis and urethritis. Between June 2001 and December 2003, a total of 33 patients visited the Department of Urology, Hanyang University Guri Hospital and were examined for T. vaginalis infection by PCR and culture in TYM medium. For the PCR, we used primers based on a repetitive sequence cloned from T. vaginalis (TV-E650). Voided bladder urine (VB1 and VB3) was sampled from 33 men with symptoms of lower urinary tract infection (urethral charge, residual urine sensation, and frequency). Culture failed to detect any T. vaginalis infection whereas PCR identified 7 cases of trichomoniasis (21.2%). Five of the 7 cases had been diagnosed with prostatitis and 2 with urethritis. PCR for the 5 prostatitis cases yielded a positive 330 bp band from bothVB1 and VB3, whereas positive results were only obtained from VB1 for the 2 urethritis patients. We showed that the PCR method could detect T. vaginalis when there was only 1 T. vaginalis cell per PCR mixture. Our results strongly support the usefulness of PCR on urine samples for detecting T. vaginalis in chronic prostatitis and urethritis patients.

Keywords: Trichomonas vaginalis, PCR, prostatitis, urethritis, urine

Trichomonas vaginalis causes an estimated 174 million sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide annually [1]. In men, trichomoniasis can be associated with urethritis and prostatitis. In addition, infection by T. vaginalis may increase the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The estimated prevalence of trichomoniasis in men ranges from 0% in asymptomatic men to 58% in high-risk adolescents. Generally, however, the prevalence of trichomoniasis in men is estimated to be low [2].

Prostatitis is the most common urological diagnosis in men below 50 years of age, accounting for 8% of all office visits to urologists [3]. It has been noted that about 50% of men of fertile age have clinical signs of chronic prostatitis at least once in their lifetimes. The most common form of prostatitis is chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). However, despite its prevalence, prostatitis remains a poorly understood disease, with the majority of diagnosed cases in humans being of unknown etiology. No reference standard exists for diagnostic testing for CP/CPPS, and the condition is mostly recurrent, with relapses lasting for varying periods [4]. Studies of men with chronic prostatitis found that the cause was an infection in 71.0-74.2%, with trichomoniasis as the specific infection in 10.5-19.0% of cases [5,6]. Urethritis is a common, global problem with important health consequences that include pain, epididymitis, and infertility. T. vaginalis has been reported in 13% of patients with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) [7].

Various methods have been used to diagnose trichomoniasis, such as wet mount, the Papanicolaou test and culture. Wet mount examination is straightforward and rapid, but more than 103/ml of live protozoa are required for detection, and cultures require inocula of 300-500 trichomonads/ml and specialized medium, as well as 2-5 days to make a diagnosis [8]. During recent years, molecular biological techniques have provided new approaches to the diagnosis of T. vaginalis infection [2,9]. In our previous study [10], a highly sensitive and specific PCR method was developed using primers based on the repetitive sequence of T. vaginalis (TV-E650); originally cloned by Paces et al. [11]. This PCR-based method had a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, and was able to detect T. vaginalis in vaginal discharge fluid at a concentration as low as 1 cell per PCR mixture.

In Korea, PCR has not been used for diagnosis of T. vaginalis infection in male patients with low urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) except for the application of multiplex PCR in the case of 11 patients with category III chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome [12]. In the present study, we used PCR to diagnose T. vaginalis infection in 33 patients with chronic recurrent prostatitis or urethritis.

Thirty-three Korean men (average age 36.7±9.1 years) who visited Hanyang University Guri Hospital from June 2001 through December 2003 were selected for this study. Most of the patients complained of LUTS such as urethral charge, residual urine sensation, and frequency. We used specimens from pre-prostatic massage, expressed prostatic secretion (EPS), and post-prostatic massage (2-glass test). We examined midstream pre-prostatic massage urine samples (Pre-M and VB1), EPS, and urine specimens after prostatic massage (Post-M and VB3). The men were diagnosed as chronic prostatitis or urethritis by Pre-M and Post-M specimens. Urethritis was defined as a urethral swab Gram stain with≥5 polymorphonuclear cells per oil immersion field. We identified chronic prostatitis (CP/CPPS Category IIIA by the National Institutes of Health classification) as greater than 10 white blood cells per high power field in expressed prostatic secretions obtained by prostatic massage.

For urine sediment cultures, first-void urine (VB1) and post-prostate massage urine (VB3) samples (30 ml each) were centrifuged at room temperature for 10 min at 1,500 g. Each supernatant was aspirated, and 50 µl of sediment was put into a tube containing 5 ml of TYM media for culture [10]. The inoculum in TYM medium was grown in a 37℃ incubator for 2-5 days and the presence of the parasite was confirmed by light microscopy. For the PCR, 5 µl of urine sediment was mixed with 20 µl of Gene Releaser® (BioVentures Inc., Murfreesboro, Tennessee, USA), and the mixture was boiled for 5 min using a microwave oven. Then, it was centrifuged, and 3 µl of supernatant was added to the PCR reaction mixture. The primers were based on the T. vaginalis-specific repetitive DNA sequence in clone TV-E650-1 [11]. The sequences of the PCR primers were as follows: the primer 1: 5' gagttagggtataatgtttgatgtg 3'; the primer 2: 5' agaatgtgatagcgaaatggg 3'. The PCR reaction mixture contained primer 1 (10 pmol/µl) 1.5 µl, primer 2 (10 pmol/µl) 1.5 µl, dNTPs (2.5 mM each) 2 µl, Taq polymerase (5 U/µl) 0.1 µl, pre-treated vaginal discharge 3 µl, 10×PCR buffer 2 µl, and distilled water 9.9 µl. The DNA was denatured for 5 min at 95℃, followed by cycles of 30 sec denaturation at 94℃, 10 sec annealing at 50℃, and 30 sec extension at 72℃. Total 35 reaction cycles were run. To avoid product carryover, PCR reactions were set up in an area physically separate from all activities involving amplified target sequences, thermocycling and the running of gels.

To assess the sensitivity of PCR, T. vaginalis was counted with a hemocytometer, and the number of trophozoites was adjusted with PBS to 1, 3, 10, 50, 100, and 10,000 cells (T. vaginalis) per PCR mixture. We tested the specificity of the PCR with DNA extracted from Candida albicans, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Escherichia coli.

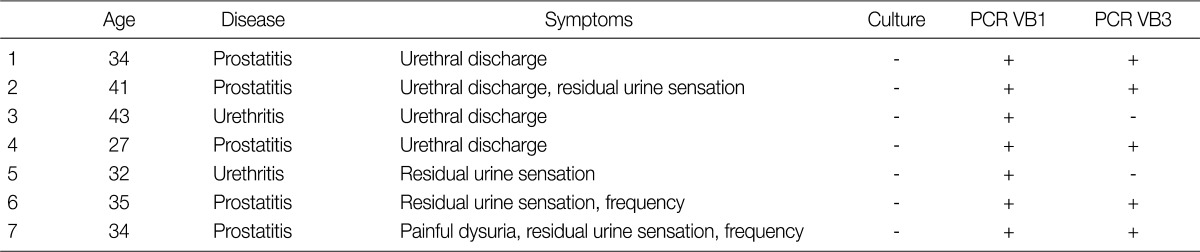

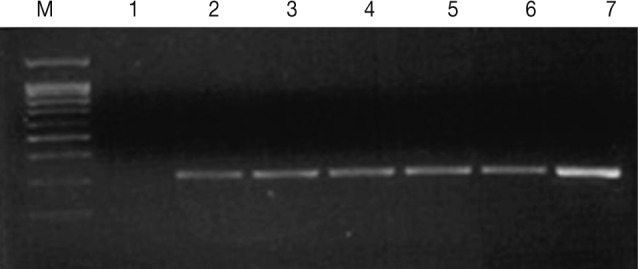

By culture, we failed to detect any T. vaginalis whereas PCR identified 7 cases of trichomoniasis among the 33 men (21.2%). PCR for the 5 prostatitis cases yielded a positive 330 bp band from both VB1 and VB3 whereas positive results were only obtained using VB1 for the 2 urethritis patients (Table 1). Thus, since the VB1 samples gave positive results in both the prostatitis and urethritis patients, VB1 (first voided urine) specimens, which are collected easily, are suitable for PCR diagnosis of T. vaginalis infection in men. The PCR method was sensitive enough to detect T. vaginalis at a concentration as low as 1 cell per PCR mixture (Fig. 1). Also, when DNAs from pathogens causing STI such as C. albicans, C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhea, and E. coli were examined to test the specificity of the PCR, no amplification was obtained. In addition, we tested 84 male outpatients (average age 42.7±10.8 years) without lower urinary tract symptoms who visited Hanyang University Health Promotion Center for routine checkups, and they also gave no positive outcomes for T. vaginalis by PCR or by culture (data not shown). To estimate the prevalence of T. vaginalis infection it will be necessary to test many more patients with recurrent lower urinary tract infections.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients giving positive results in PCR for Trichomonas vaginalis

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products (330 bp) from increasing numbers of T. vaginalis. Lane 1: distilled water (negative control), Lanes 2-7: 1, 3, 10, 50, 100, and 10,000 cells (T. vaginalis).

Several PCR assays have been developed to detect T. vaginalis in urine or vaginal specimens from women. However, detection of T. vaginalis in men by PCR methods has received less attention. Urine-based PCR assays for men have been described; Schwebke and Lawing [13] reported that PCR analysis of urine specimens from men attending an STD clinic was far more sensitive than culture for detecting trichomonas, and its prevalence was high (17%; 52/300). Wendel et al. [14] reported that the prevalence of T. vaginalis in an urban STD clinic, as tested by urine PCR and culture (13%; 47/363) was similar to that of Chlamydia (11%), and Seña et al. [15] detected T. vaginalis infection in 177 (71.7%) of 256 male partners of women with trichomoniasis using urine PCR-ELISAs, whereas urine or urethral cultures were positive in only 40 of the men (15.6%). These reports support our conclusion that the PCR method using urine samples is suitable for detecting T. vaginalis infection.

In conclusion, PCR using urine specimens is far more sensitive than culture for detecting Trichomonas. PCR screening of T. vaginalis among men with recurrent LUTS should be considered a part of any public health initiatives to control trichomoniasis.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaydos-Daniels SC, Miller WC, Hoffman I, Banda T, Dzinyemba W, Martinson F, Cohen MS, Hobbs MM. Validation of a urine-based PCR-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for use in clinical research settings to detect Trichomonas vaginalis in men. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:318–323. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.318-323.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thumbikat P, Shahrara S, Sobkoviak R, Done J, Pope RM, Schaeffer AJ. Prostate secretions from men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome inhibit proinflammatory mediators. J Urol. 2010;184:1536–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lan T, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin W, Zhang J, Wang Z, Zhang W, Zhang X, Yuan J, Wang H. Influence of environmental factors on prevalence, symptoms, and pathologic process of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in northwest China. Urology. 2011;78:1142–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skerk V, Schönwald S, Krhen I, Markovinović L, Beus A, Kuzmanović NS, Kruzić V, Vince A. Aetiology of chronic prostatitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:471–474. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skerk V, Krhen I, Schonwald S, Cajic V, Markovinovic L, Roglic S, Zekan S, Andracevic AT, Kruzic V. The role of unusual pathogens in prostatitis syndrome. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:S53–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwebke JR, Rompalo A, Taylor S, Seña AC, Martin DH, Lopez LM, Lensing S, Lee JY. Re-evaluating the treatment of nongonococcal urethritis: emphasizing emerging pathogens: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:163–170. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garber GE, Sibau L, Ma R, Proctor EM, Shaw CE, Bowie WR. Cell culture compared with broth for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1275–1279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.7.1275-1279.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munson E, Napierala M, Basile J, Miller C, Burtch J, Hryciuk JE, Schell RF. Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification-based analyte-specific reagent and alternative target testing of primary clinical vaginal saline suspensions. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu JS, Chung HL, Min DY, Cho YH, Ro YS, Kim SR. Diagnosis of trichomoniasis by polymerase chain reaction. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40:56–60. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paces J, Urbánková V, Urbánek P. Cloning and characterization of a repetitive DNA sequence specific for Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim TH, Kim HR, Myung SC. Detection of nanobacteria in patients with chronic prostatitis and vaginitis by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:194–199. doi: 10.4111/kju.2011.52.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwebke JR, Lawing LF. Improved detection by DNA amplification of Trichomonas vaginalis in males. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3681–3683. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3681-3683.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendel KA, Erbelding EJ, Gaydos CA, Rompalo AM. Use of urine polymerase chain reaction to define the prevalence and clinical presentation of Trichomonas vaginalis in men attending an STD clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:151–153. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sena AC, Miller WC, Hobbs MM, Schwebke JR, Leone PA, Swygard H, Atashili J, Cohen MS. Trichomonas vaginalis infection in male sexual partners: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:13–22. doi: 10.1086/511144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]