Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

In this study, we examined how often US youths reported having complete parental restrictions on watching R-rated movies. In addition, we assessed the relationship between parental R-rated movie restrictions and adolescents' sensation seeking and how this interplay is related to smoking onset.

METHODS:

Data from a 4-wave longitudinal study of 6522 adolescents (10–14 years of age) who were recruited through a random-digit-dial telephone survey were used. At baseline, subjects were nationally representative of the US population. Subjects were monitored for 2 years and queried about their smoking status, their sensation-seeking propensity, and how often they were allowed to watch R-rated movies. A cross-lagged model combined with survival analysis was used to assess the relationships between parental R-rated movie restrictions, sensation-seeking propensity, and risk for smoking onset.

RESULTS:

Findings demonstrated that 32% of the US adolescents reported being completely restricted from watching R-rated movies by their parents. Model findings revealed that adolescents' sensation seeking was related to greater risk for smoking onset not only directly but also indirectly through their parents becoming more permissive of R-rated movie viewing. Parental R-rated movie restrictions were found to decrease the risk of smoking onset directly and indirectly by changing children's sensation seeking.

CONCLUSIONS:

These findings imply that, beyond direct influences, the relationship between adolescents' sensation seeking and parental R-rated movie restrictions in explaining smoking onset is bidirectional in nature. Finally, these findings highlight the relevance of motivating and supporting parents in limiting access to R-rated movies.

Keywords: media, parenting, R-rated movie restrictions, sensation seeking, smoking onset

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Evidence has shown that sensation seeking is positively related and parental restrictions on R-rated movies are negatively related to smoking onset in adolescence.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

The current study revealed that, beyond direct influences, the relationship between adolescents' sensation seeking and parental R-rated movie restrictions in explaining smoking onset is bidirectional in nature.

Today's youths consume vast amounts of media; children and adolescents in the United States spend an average of nearly 6.5 hours per day using media, with the majority of time spent viewing television and movies.1 When watching popular movies, youths are exposed to many risky behaviors, including smoking,2–5 which rarely is displayed with negative health consequences and most often is portrayed in a positive manner or glamorized to some extent.2,6,7 Empirical studies demonstrated a dose-response relationship between the amount of movie smoking that adolescents view and the likelihood that they will begin smoking, independent of other important risk factors for smoking.8–11 Attributable-fraction estimates suggested that movie smoking exposure accounts for one-third to one-half of adolescent smoking onset.12–14 Given this estimate, reducing movie smoking exposure among youths could be an effective prevention strategy.

Although smoking is portrayed in all movie rating categories, it is most prevalent in R-rated movies,2,5,15–17 which are restricted at the box office to individuals ≥17 years of age unless parental permission is provided. Therefore, parental enforcement of R-rated movie restrictions should limit movie smoking exposure to youths <17 years of age. Several US cross-sectional studies showed that adolescents who reported R-rated movie restrictions had actual lower levels of exposure to R-rated movies and were less likely to have ever tried smoking, compared with those who had no restrictions.18,19 R-rated movie restrictions also were related to lower attitudinal susceptibility to smoking among adolescents who had never tried smoking.20 Furthermore, parental prohibitions on viewing R-rated movies were associated with lower risks for smoking, with controlling for general parental monitoring.21 Similar prospective findings were reported, with children whose parents restricted their R-rated movie exposure seeing less movie smoking and being at lower risk for initiation of smoking within the subsequent 1 or 2 years.22 These findings were replicated in Germany; adolescents who reported parental prohibitions on viewing of FSK-16 movies (no one <16 years of age allowed in theaters) were at lower risk of future smoking. This effect was mediated in part through lower levels of exposure to movie smoking portrayals.23

Holding the line on R-rated movie viewing may not be easy for some parents, however. As early as the 1960s, Bell24 argued that parenting is a bidirectional influence and suggested that children may modulate their own socialization on the basis of their own behavior. Empirical evidence has supported the idea proposed by Bell,24 by demonstrating that parenting changes children's problem behaviors and vice versa.25,26 One parenting challenge involves children with high sensation-seeking propensity, a trait that has been found to be a strong predictor of smoking.27 Sensation seeking describes the tendency to seek novel, complex, and intense sensations and experiences and the willingness to take risks for such experiences.28 It is reasonable to expect that sensation-seeking children may affect parenting behaviors, especially when children grow into adolescence and are more able to select their environments and experiences.29

Although 58% of the total variance in sensation seeking was found to be explained by genetic influences,28 this trait is not as fixed and stable as thought previously. Instead, sensation-seeking levels seem to change slightly across the life span, with an increase during adolescence, which might be explained by social/environmental influences.28,30,31 One of these influences seems to come from the media. A recent study on sensation seeking and R-rated movie viewing indicated a short-term reciprocal relationship between the 2 constructs; sensation-seeking adolescents were more likely to view R-rated movies, and exposure to such movies strengthened sensation-seeking tendencies.32 However, that study also revealed that, over a longer period, R-rated movie exposure was associated primarily with increases in sensation seeking; watching R-rated movies increased sensation seeking more than sensation seeking increased viewing of R-rated movies.32 Given this finding, it seems reasonable to expect that parents who restrict their children from watching R-rated movies may protect them from smoking onset in 2 ways, that is, by limiting movie-induced influences to smoke and by decreasing growth in sensation seeking triggered by movies.

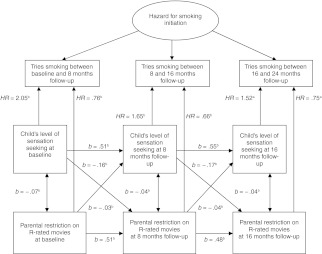

This study builds on previous findings by establishing the prevalence of full restrictions on R-rated movies within a nationally representative US sample of adolescents. Furthermore, we examined the interplay between parental R-rated movie restrictions and adolescents' levels of sensation seeking, to assess mechanisms through which R-rated movie restrictions might affect smoking. To investigate this, we tested a cross-lagged model embedded within a survival model (Fig 1). We hypothesized that higher levels of sensation seeking would be related to smoking onset directly but also indirectly through a loosening of parental R-rated movie restrictions, presumably because sensation-seeking youths sway their parents' rules. R-rated movie restrictions were hypothesized to be related to lower risk of smoking directly and indirectly through lower levels of sensation seeking. The analyses controlled for other potential influences, namely, exposures to other media, social influences to smoke, and parenting style.

FIGURE 1.

Hazard model for smoking initiation explained by parental R-rated movie restrictions and children's sensation seeking. For simplicity, pathways for the covariates, stability pathways between baseline and 24-month follow-up evaluations, and extra lagged paths from the repeated measurements of R-rated movie restrictions and sensation seeking with respect to smoking initiation at later time intervals are not displayed. b is an unstandardized estimate. a P < .01; b P < .001.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

Data from a longitudinal study on media and health that included 6522 US adolescents 10 to 14 years of age were used. In 2003, adolescents were recruited by using random-digit dialing, with 3 follow-up evaluations at 8-month intervals. Telephone surveys were administered by trained interviewers. To protect confidentiality, adolescents could answer sensitive questions by pressing numbers on the telephone. All aspects of this project were approved by the institutional review boards at Dartmouth Medical School and Westat (Rockville, MD), a survey research firm. Of the baseline subjects, 5503 (84%) participated at the 8-month follow-up evaluation, 5019 (77%) at the 16-month follow-up evaluation, and 4574 (70%) at the 24-month follow-up evaluation. Demographic characteristics of the baseline sample were nationally representative of the US population 10 to 14 years of age regarding gender, socioeconomic status, and Census region but with a slight overrepresentation of Hispanic adolescents and underrepresentation of black adolescents. Details concerning the project were described previously.13 Attrition analyses of data for the subjects included in this study revealed differences between those retained in all 4 surveys and those lost to follow-up monitoring; lost subjects were younger, had lower academic performance, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to report limits on R-rated movies. In addition, these subjects were more likely to be black and to have parents or friends who smoked.

Measures

Smoking Onset

The primary outcome was the transition from never smoking to ever smoking. To assess smoking status, adolescents were asked at each wave, “Have you ever tried smoking a cigarette, even just a puff (yes or no)?” Change in smoking status was assessed for 3 intervals, that is, baseline to 8 months, 8 months to 16 months, and 16 months to 24 months.

Parental R-Rated Movie Restrictions

R-rated movie restrictions were measured by asking the adolescents at each wave, “How often do your parents let you watch movies or videos that are rated R (never, once in a while, sometimes, or all the time)?” The internal validity of this measure was demonstrated through strong positive associations with actual R-rated movie exposure.18,22 For ease of interpretation, the responses were reversed, with higher scores reflecting higher restriction levels.

Sensation Seeking

Sensation seeking was established with a scale addressing 2 important components of sensation seeking,28 that is, thrill and adventure seeking (“I like to do scary things” and “I like to do dangerous things”) and boredom susceptibility (“I often think there is nothing to do”). In addition, the intensity-seeking component (“I like to listen to loud music”) of the Arnett Inventory of Sensation Seeking33 was included. Adolescents were asked to indicate how much the phrases were like them (“not like you,” “a little like you,” “a lot like you,” or “just like you”). Scores were averaged. Cronbach's α values varied between .57 and .62 across waves. Assessment of sensation seeking with this validated scale was found to be a good predictor of smoking.34

Covariates

A number of possible confounders, assessed at baseline, were included in the analyses. In addition to the demographic characteristics of gender, age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, we included adolescents' academic performance, rebelliousness, involvement in extracurricular activities, daily television exposure, and number of movies watched per week. Parenting style was defined on the basis of levels of parental support and control, as assessed with the Authoritative Parenting Index.35 Parental support involves how adolescents think their parents respond to their needs and empathize with their concerns. Parental control relates to how adolescents think their parents set and enforce limits. Parental smoking and parental disapproval of smoking36 also were included. We decided not to control for sibling smoking and friend smoking because we considered both to be mediators of the R-rated movie parenting effect on behavior. Including those factors would overspecify the model and result in underestimates of parenting effects on behavior. Sibling smoking was rejected as a covariate because sibling smoking was expected to be affected by parental R-rated movie restrictions applied at the household level. In addition, changes in friend smoking have been found to mediate the movie smoking effect on behavior; therefore, friend smoking was rejected as a covariate.37,38 More specifically, by being strict regarding R-rated movie viewing, parents decrease the risk of their children having a smoking sibling because that sibling presumably has comparable restrictions. Parents' restrictions regarding R-rated movies also may decrease the odds that their children will affiliate with peers who smoke. An overview of the covariates and the reliabilities of the scales is provided in Appendix 1.

Strategy of Analyses

To establish the population-based prevalence of parental R-rated movie restrictions in the US population, we calculated proportions for the total sample (N = 6522) by using survey population weights. The main analysis involved an assessment of time to smoking onset by using a discrete-time survival analysis, which models the hazard probability of smoking onset occurring in a specific time interval, given that it has not happened yet.39 Therefore, we selected the baseline never-smokers (N = 5829). To examine the bidirectional relationship between R-rated movie restrictions and sensation seeking and their direct and indirect associations with smoking onset, we combined a cross-lagged panel model with the survival analyses. Longitudinal cross-lagged modeling is an appropriate way to establish the causal predominance between 2 constructs, because bidirectional associations between the constructs can be examined with controlling for effects at earlier points in time.40,41 The model, as illustrated in Fig 1, was tested by using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA).42 Parameters in the models were estimated by applying the maximal likelihood estimator. The model was built in steps, with the cross-lagged part being tested first for an examination of model fit. Fit indices used to evaluate the model included a χ2 goodness-of-fit test (nonsignificant values indicate good fits), the comparative fit index (scores of >0.95 indicate better fits), the root mean square error of approximation (values of <0.05 indicate good fits), and the standardized root mean square residual (values of <0.08 indicate good fits).43,44 Missing values were imputed through multiple imputation by using functions in the missing data library in S-Plus (Insightful Corp, Seattle, WA).45,46 The combined data for the cross-lagged/survival model converged more quickly with 15 imputed data sets than did the model that used a likelihood-based approach to missing data. Convergence of the data augmentation algorithm was checked through inspection of an autocorrelation plot of the worst linear function of the parameters.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

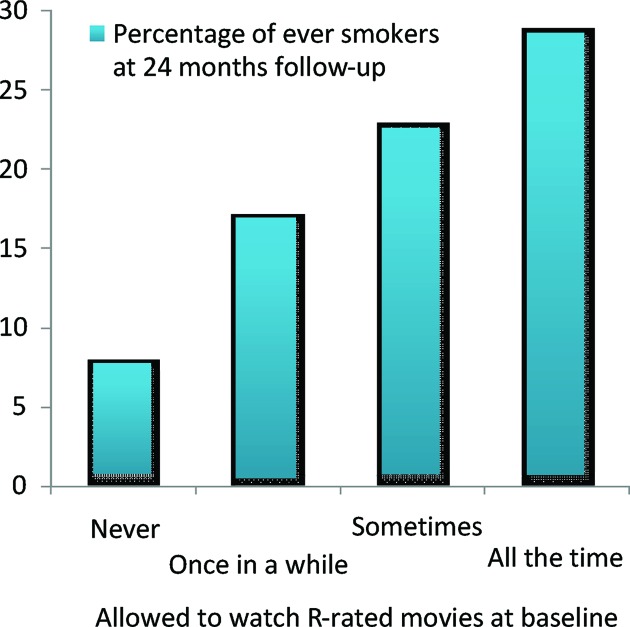

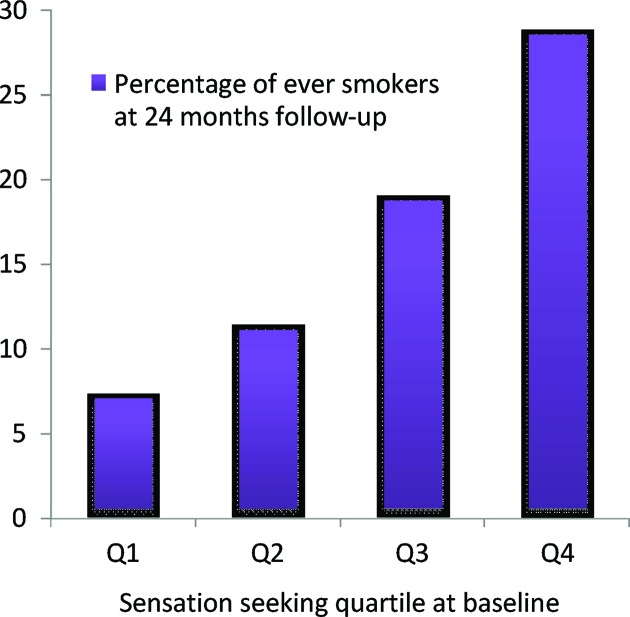

The weighted prevalence of reporting full parental restrictions on watching R-rated movies at baseline was 32% among the total sample (N = 6522). Descriptive statistics for child and social/environmental characteristics of the nonsmoking adolescents at baseline (N = 5829) are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of R-rated movie restrictions, mean levels of sensation seeking, and the incidence of smoking onset across waves are presented in Table 2. Table 2 shows that the prevalence of full restrictions on watching R-rated movies among the baseline never-smokers was 33% (unweighted). The prevalence of R-rated movie restrictions decreased significantly over time, with only 12% still reporting complete restrictions at 24 months. The average level of sensation seeking increased over time, as did the prevalence of smoking, with ∼5% of previous nonsmokers trying smoking during each time interval. Figures 2 and 3 display the crude linear relationships between baseline R-rated movie restrictions and sensation seeking, respectively, and ever-smoking prevalence at 24 months, which indicate that parental lenience concerning R-rated movies and higher levels of sensation seeking were both related to being a future ever-smoker.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Child and Social/Environmental Characteristics According to Parental R-Rated Movie Restrictions for Baseline Never-Smokers

| Characteristic | Total (N = 5829) | Full Restrictions on Watching R-Rated Movies (N = 1922) | Watching R-Rated Movies Allowed at Least Sometimes (N = 3878) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, % | |||

| Male | 51 | 40 | 56 |

| Female | 49 | 60 | 44a |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| White | 62 | 67 | 60 |

| Nonwhite | 38 | 33 | 40a |

| Academic performance, % | |||

| Average or below | 25 | 19 | 28 |

| Good | 42 | 40 | 44 |

| Excellent | 32 | 41 | 28a |

| Television exposure per day, % | |||

| None | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| <1 h | 20 | 23 | 18 |

| 1–2 h | 47 | 48 | 47 |

| 3–4 h | 20 | 15 | 22 |

| >4 h | 8 | 6 | 9a |

| Movies watched per week, % | |||

| None | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 1 or 2 | 37 | 44 | 33 |

| 3 or 4 | 31 | 29 | 33 |

| ≥5 | 29 | 22 | 33a |

| Having one or both parents smoking, % | 28 | 20 | 32a |

| Having older sibling smoking, % | 12 | 7 | 15a |

| Having smoking friends, % | 17 | 7 | 22a |

| Strong parental disapproval of smoking, % | 94 | 96 | 93a |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 12.27 ± 1.41 | 11.76 ± 1.33 | 12.52 ± 1.38b |

| Extracurricular activity score, mean ± SD | 2.85 ± 0.50 | 2.79 ± 0.50 | 2.88 ± 0.49b |

| Sensation-seeking score, mean ± SD | 1.93 ± 0.59 | 1.71 ± 0.53 | 2.04 ± 0.59b |

| Rebelliousness score, mean ± SD | 1.40 ± 0.40 | 1.28 ± 0.33 | 1.46 ± 0.42b |

| Parenting style score, mean ± SD | |||

| Support | 3.29 ± 0.45 | 3.37 ± 0.42 | 3.25 ± 0.45b |

| Control | 3.35 ± 0.49 | 3.47 ± 0.44 | 3.30 ± 0.50b |

The scores for sensation seeking ranged between 1 and 4, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of sensation seeking. The same scale structures applied to the covariates of extracurricular activities, rebelliousness, and parenting style. For ease of comparison, adolescents who reported that their parents allowed them to watch R-rated movies once in a while, sometimes, or all of the time were combined in a group with parents who allowed R-rated movie watching at least sometimes.

The χ2 tests indicated significant differences in gender (χ21 = 131.18 [N = 5799]; P < .001), race (χ21 = 30.01 [N = 5791]; P < .001), academic performance (χ22 = 114.82 [N = 5787]; P < .001), television exposure per day (χ24 = 90.26 [N = 5792]; P < .001), movies watched per week (χ23 = 130.30 [N = 5791]; P < .001), having one or both parents smoking (χ21 = 126.09 [N = 5682]; P < .001), having an older sibling smoking (χ21 = 61.12 [N = 5769]; P < .001), having smoking friends (χ21 = 197.17 [N = 5788]; P < .001), and strong parental disapproval regarding smoking (χ21 = 17.94 [N = 5759]; P < .001) between adolescents who were allowed to watch R-rated movies at least sometimes and adolescents who reported having full restrictions.

Findings from t tests indicated significant differences in age (t3953.52 = 20.35 [N = 5800]; P < .001), extracurricular activities (t5794 = 6.29 [N = 5796]; P < .001), sensation seeking (t4238.20 = 21.33 [N = 5799]; P < .001), rebelliousness (t4775.31 = 17.34 [N = 5799]; P < .001), parental support (t4050.94 = −10.52 [N = 5799]; P < .001), and parental control (t4294.88 = −13.51 [N = 5797]; P < .001) between adolescents who were allowed to watch R-rated movies at least sometimes and adolescents who reported full restrictions.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Parental R-Rated Movie Restrictions, Mean Levels of Sensation Seeking, and Incidence of Smoking Initiation During Measurement Periods

| Characteristic | Baseline | 8 mo | 16 mo | 24 mo | From Baseline to 8 mo | From 8 mo to 16 mo | From 16 mo to 24 mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full restriction on R-rated movies, % | 33 | 19 | 16 | 12 | |||

| Sensation-seeking score, mean ± SD | 1.93 ± 0.59 | 1.97 ± 0.58 | 2.03 ± 0.61 | 2.08 ± 0.63 | |||

| Tried smoking, % | 0 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

For ease of interpretation, only prevalence rates of full restrictions on watching R-rated movies are displayed here. In the model, these variables were used as continuous measures. A significant time effect was found for parental R-rated movie restrictions (Wilks' Λ = 0.68, F3,3700 = 573.32; P < .001), sensation seeking (Wilks' Λ = 0.92, F3,3723 = 114.59; P < .001), and prevalence of ever smoking (Wilks' Λ = 0.85, F3,3726 = 226.99; P < .001).

FIGURE 2.

Proportions of baseline never-smokers who tried smoking by the 24-month follow-up evaluation, according to parental R-rated movie restrictions at baseline (never-smokers monitored successfully to 24 months, N = 4167).

FIGURE 3.

Proportions of baseline never-smokers who tried smoking by the 24-month follow-up evaluation, according to levels of sensation seeking at baseline (never-smokers monitored successfully to 24 months, N = 4167). Q indicates quartile.

Model Findings

The cross-lagged part of the model demonstrated excellent fit (χ22 = 3.08 [N = 5829]; P = .21; comparative fit index: 1.00; root mean square error of approximation: 0.01; standardized root mean squared residual: <0.01). Findings of the full model are presented in Fig 1 and Table 3. Cross-lagged paths revealed significant negative associations between adolescents' levels of sensation seeking and later levels of parental restrictiveness on watching R-rated movies (baseline to 8 months, unstandardized estimate b = −0.16; P < .001; 8 months to 16 months, b = −0.17; P < .001). Restrictions also were found to be significantly related to future levels of sensation seeking (baseline to 8 months, b = −0.03; P < .001; 8 months to 16 months, b = −0.04; P < .001).

TABLE 3.

Results for Full Model of Initiation of Smoking According to Parental R-Rated Movie Restrictions and Children's Sensation Seeking

| b, Estimate ± SE | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-lagged paths | ||

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to sensation seeking at 8 mo | −0.03 ± 0.01a | 0.97 (0.95–0.99)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to sensation seeking at 16 mo | −0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.96 (0.94–0.98)a |

| Sensation seeking at baseline to restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo | −0.16 ± 0.02a | 0.85 (0.82–0.89)a |

| Sensation seeking at 8 mo to restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo | −0.17 ± 0.02a | 0.84 (0.81–0.88)a |

| Cross-sectional associations | ||

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline and sensation seeking at baseline | −0.07 ± 0.01a | 0.93 (0.91–0.95)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo and sensation seeking at 8 mo | −0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.96 (0.94–0.98)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo and sensation seeking at 16 mo | −0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.96 (0.94–0.98)a |

| Stability paths | ||

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo | 0.51 ± 0.01a | 1.67 (1.63–1.70)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo | 0.48 ± 0.01a | 1.62 (1.58–1.65)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo | 0.25 ± 0.02a | 1.28 (1.23–1.34)a |

| Sensation seeking at baseline to sensation seeking at 8 mo | 0.51 ± 0.01a | 1.67 (1.63–1.70)a |

| Sensation seeking at 8 mo to sensation seeking at 16 mo | 0.55 ± 0.02a | 1.73 (1.67–1.80)a |

| Sensation seeking at baseline to sensation seeking at 16 mo | 0.21 ± 0.02a | 1.23 (1.19–1.28)a |

| Hazard risks for smoking initiation | ||

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to initiation between baseline and 8 mo | −0.27 ± 0.06a | 0.76 (0.68–0.86)a |

| Sensation seeking at baseline to initiation between baseline and 8 mo | 0.72 ± 0.10a | 2.05 (1.69–2.50)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | −0.41 ± 0.10a | 0.66 (0.55–0.81)a |

| Sensation seeking at 8 mo to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | 0.50 ± 0.12a | 1.65 (1.30–2.09)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | −0.29 ± 0.09b | 0.75 (0.63–0.90)b |

| Sensation seeking at 16 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | 0.42 ± 0.13b | 1.52 (1.18–1.96)b |

| Lagged paths | ||

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | −0.31 ± 0.09a | 0.73 (0.62–0.87)a |

| Sensation seeking at baseline to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | 0.80 ± 0.11a | 2.23 (1.78–2.79)a |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | −0.45 ± 0.09a | 0.64 (0.53–0.77)a |

| Sensation seeking at 8 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | 0.65 ± 0.13a | 1.91 (1.49–2.45)a |

P < .001.

P < .01.

Findings for the hazard part of the full model demonstrated direct prospective associations between each repeated measure of sensation seeking and smoking onset over the subsequent 8 months (baseline to 8 months, hazard ratio [HR]: 2.05 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.69–2.50]; 8 months to 16 months, HR: 1.65 [95% CI: 1.30–2.09]; 16 months to 24 months, HR: 1.52 [95% CI: 1.18–1.96]). Negative associations were found between each repeated measure of R-rated movie restrictions and smoking (baseline to 8 months, HR: 0.76 [95% CI: 0.68–0.86]; 8 months to 16 months, HR: 0.66 [95% CI: 0.55–0.81]; 16 months to 24 months, HR: 0.75 [95% CI: 0.63–0.90]). We estimated that full parental R-rated movie restrictions could make a two- to threefold difference in the risk of initiating smoking (Table 4). We also tested whether the expected indirect effects in the model were significant by testing the product of the paths involved against the null hypothesis of 0 by using Wald tests. Findings from these tests are presented in Table 5 and indicated that all indirect paths were significant.

TABLE 4.

Effects on Smoking Onset of High Versus Low Levels of Sensation Seeking and Parental R-Rated Movie Restrictions

| Variable | HR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to 8 mo | 8–16 mo | 16–24 mo | |

| Sensation-seeking | 4.03 (2.75–5.92)a | 3.15 (2.21–4.49)a | 2.65 (1.85–3.80)a |

| Parental R-rated movie restrictions | 2.22 (1.52–3.24)a | 3.03 (1.90–4.81)a | 3.32 (2.11–5.22)a |

P < .001.

TABLE 5.

Wald Tests of Indirect Effects in Model

| Test | df | Robust |

Standard |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P | χ2 | P | ||

| All 4 indirect effects simultaneously | 4 | 77.34 | .0001 | 81.74 | .0001 |

| Sensation-seeking at baseline to restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | 1 | 14.14 | .0002 | 14.77 | .0001 |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at baseline to sensation seeking at 8 mo to initiation between 8 mo and 16 mo | 1 | 11.22 | .0008 | 11.75 | .0006 |

| Sensation seeking at 8 mo to restrictions on R-rated movies at 16 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | 1 | 10.44 | .0012 | 10.41 | .0013 |

| Restrictions on R-rated movies at 8 mo to sensation seeking at 16 mo to initiation between 16 mo and 24 mo | 1 | 18.94 | .0001 | 19.44 | .0001 |

Finally, the full model included lagged paths between the repeated measures of R-rated movie restrictions and sensation seeking and smoking onset within the subsequent time interval. Because we were interested in interpreting the lagged effects of each predictor with controlling for change in the predictor, we summed the lagged and concurrent paths and tested this effect against the null value of 0.47 Findings revealed that R-rated movie restrictions at baseline also predicted lower likelihood of onset between 8 months and 16 months (HR: 0.73 [95% CI: 0.62–0.87]) and restrictions at 8 months predicted lower likelihood of onset between 16 months and 24 months (HR: 0.64 [95% CI: 0.53–0.77]). Moreover, findings demonstrated that baseline sensation seeking predicted smoking onset between 8 months and 16 months (HR: 2.23 [95% CI: 1.78–2.79]) and sensation seeking at 8 months predicted onset between 16 months and 24 months (HR: 1.91 [95% CI: 1.49–2.45]).

Sensitivity Analyses

As a sensitivity check, we tested whether controlling for friends' and sibling smoking might alter the main findings. With inclusion of these variables, the findings remained the same, albeit with somewhat smaller estimates for some of the effect sizes.

DISCUSSION

The current findings demonstrated that only a minority (32%) of US adolescents 10 to 14 years of age reported full R-rated movie restrictions, which is consistent with earlier regional reports.18–20,22 In investigating how the interplay between adolescents' sensation seeking and parental R-rated movie restrictions might explain smoking onset, we found that adolescents with lower levels of sensation seeking27 and those who reported R-rated movie restrictions were at lower risk for trying smoking.18–23 The results also revealed negative associations between adolescents' levels of sensation seeking and later R-rated movie restrictions, which indicates that sensation-seeking adolescents are at higher risk for starting to smoke not only directly but also indirectly through changes in parenting. Sensation-seeking adolescents seem to influence their parents to become more indulgent regarding their movie viewing, which subsequently is related to higher risks for smoking. Although the present findings support the notion that children influence their own socialization,24–26,29 the question remains how. Sensation seekers may evoke different parenting behaviors. For example, parents may prefer to keep them indoors to prevent exposure to the experiences they seek but in so doing allow access to R-rated movies. Alternatively, these adolescents may change their socialization actively by being more proactive in their pursuit of R-rated movies, by insisting on watching them, or by watching them without permission. Moreover, the findings seem to point to a bidirectional relationship, which suggests that parents also are able to modify their children's behavioral tendencies through their parenting. By being strict regarding R-rated movies, parents may play a part in preventing their children from developing higher levels of sensation seeking and associated risk for smoking. Finally, these findings also demonstrated that R-rated movie restrictions affected smoking onset not only at the next follow-up evaluation but also at the subsequent one, which indicates that being strict concerning R-rated movies is fruitful not just in the short term. Not surprisingly, sensation seeking also was related to smoking onset at later points in time.

As with any study, there are some limitations. First, the findings might have been affected by selective attrition. However, this concern regarding bias has been diminished through the inclusion of adolescents with incomplete data, through imputation. Second, the reliability of the sensation-seeking scale was marginal, which might have attenuated the effect sizes. It is important to note, however, that, like other short measures of sensation seeking,34 this scale seems to be a strong predictor of smoking despite not capturing the construct of sensation seeking as reliably as longer measures. Third, although we controlled for a range of factors that are known to affect youth smoking, there may be other confounding factors. For instance, sensation-seeking children are likely to have sensation-seeking parents, which might result in those parents being less likely to keep their sensation-seeking children away from risky situations (such as watching R-rated movies) because they themselves like sensation seeking. This might have resulted in an underestimation of the impact of parenting in this study.29 It would be an interesting avenue for future research to explore how parents' own levels of sensation seeking affect the way they handle their children. Finally, the impact of just one movie-related parenting strategy was investigated in our study, whereas other investigators examined other aspects of movie-related parenting, such as parents accompanying their children to the video store, actively determining movie ratings before allowing their children to view movies, monitoring movies viewed at friends' houses, and coviewing R-rated movies.21 Because sensation-seeking adolescents are more likely to seek novel and intense sensations and experiences,28 parental movie monitoring may be particularly important because the adolescents themselves are less likely to be able to resist the temptation of watching R-rated movies. This highlights the importance of determining whether different parenting strategies related to the use of media are more or less effective for sensation-seeking adolescents.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings support a clarion call for parents to adopt active parenting regarding media during early adolescence. Given the small proportion of parents who restrict viewing of R-rated movies, it is likely that few parents are aware of the impact that risk behaviors in movies may have on their children. Many parents relax their restrictions regarding R-rated movies during adolescence, but our results suggest that continued restriction is an effective means of reducing adolescents' risk for smoking onset. Pediatricians need to reinforce strict parenting regarding media and its maintenance throughout adolescence. The finding that sensation-seeking adolescents contribute to changes in their own parenting emphasizes the importance of pediatricians finding ways to support and to motivate parents to limit access to restricted media consistently, despite their children's protests. Not all of the responsibility falls on the parents, however, especially because the present findings revealed that sensation-seeking adolescents are at greater risk for smoking directly and indirectly through changes in their parenting. Theaters and video stores should enforce policies that prevent children <17 years of age from viewing or renting movies without an accompanying parent. This may prevent sensation-seeking children from watching R-rated movies without their parents' knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant CA-077026) and by the Radboud University Nijmegen.

APPENDIX 1.

Overview of Additional Measurements

| Variable | Survey Questions | Response Options |

|---|---|---|

| Academic performance | How would you describe your grades in school? | Below average, average, good, or excellent |

| Rebelliousness (6-item index; Cronbach's α = .74) | I get in trouble in school. | Not like you, a little like you, a lot like you, or just like you |

| I argue a lot with other kids. | ||

| I do things my parents wouldn't want me to do. | ||

| I do what my teachers tell me to do (reversed scale). | ||

| I argue with my teachers. | ||

| I like to break the rules. | ||

| Extracurricular activities | How often do you participate in team sports where there is a coach? | Almost every day, 1 to a few times a week, 1 to a few times a month, or never |

| How often do you participate in other sports without a coach? | ||

| How often do you attend church or other religious activities? | ||

| How often do you go to music lessons, choir, dance, or band practice? | ||

| How often do you participate in school clubs or activities like math or science clubs or the school paper? | ||

| How often do you participate in other clubs like the Boy or Girl Scouts, 4-H, or the Boys or Girls Clubs of America? | ||

| Television exposure per day | On school days, how many hours a day do you usually watch TV? Please do not include the time you use the TV to play video games. | None, <1 h, 3–4 h, or >4 h |

| Movies watched per week | About how many movies do you usually watch each week? Please include movies you see in movie theatres, on videotape or DVD, and on television. | None, 1 or 2, 3 or 4, or ≥5 |

| Parental support (9-item index; Cronbach's α = .72)a | She or he is pleased with how I behave. | Not like him or her, a little like him or her, a lot like him or her, or just like him or her |

| She or he listens to what I have to say. | ||

| She or he makes me feel better when I am upset. | ||

| She or he wants to hear about my problems. | ||

| She or he likes me just the way I am. | ||

| She or he is too busy to talk to me (reversed scale). | ||

| She or he makes rules without asking what I think (reversed scale). | ||

| She or he is always telling me what to do (reversed scale). | ||

| She or he tells me when I do a good job on things. | ||

| Parental control (7-item index; Cronbach's α = .73)b | She or he checks to see if I do my homework. | Not like him or her, a little like him or her, a lot like him or her, or just like him or her |

| She or he makes sure I tell her or him where I'm going. | ||

| She or he knows where I am after school. | ||

| She or he tells me times when I must come home. | ||

| She or he has rules that I must follow. | ||

| She or he makes sure I go to bed on time. | ||

| She or he asks me what I do with my friends. | ||

| Parental smoking | Does your mother smoke cigarettes? | No or yes |

| Does your father smoke cigarettes? | No or yes | |

| Sibling smoking | Do any of your older brothers or sisters smoke cigarettes? | No or yes |

| Friends' smoking | How many of your friends smoke cigarettes? | None, some, or most |

| Strong parental disapproval regarding smoking | If you were smoking cigarettes and your parents knew about it, would they tell you to stop?c | No or yes |

| A. Would they … | be very upset, be a little upset, or not be all that upset? | |

| B. Would they … | disapprove, have no reaction, or approve? |

Also referred to as “responsiveness.”

Also known as “demandingness.”

All adolescents were asked this question. Adolescents whose parents would tell them to stop were asked question A, and adolescents whose parents would not tell them to stop were asked question B. Adolescents who indicated that their parents would tell them to stop in combination with the expectation that their parents would be very upset were classified as perceiving strong parental disapproval of smoking.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- HR

- hazard ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

REFERENCES

- 1. Rideout V, Roberts DF, Foehr UG. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8–18 Year-Olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Everett SA, Schnuth RL, Tribble JL. Tobacco and alcohol use in top-grossing American films. J Community Health. 1998;23(4):317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glantz SA, Kacirk KW, McCulloch C. Back to the future: smoking in movies in 2002 compared with 1950 levels. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):261–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gunasekera H, Chapman S, Campbell S. Sex and drugs in popular movies: an analysis of the top 200 films. J R Soc Med. 2005;98(10):464–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mekemson C, Glik D, Titus K, et al. Tobacco use in popular movies during the past decade. Tob Control. 2004;13(4):400–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dozier DM, Lauzen MM, Day CA, Payne SM, Tafoya MR. Leaders and elites: portrayals of smoking in popular films. Tob Control. 2005;14(1):7–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McIntosh WD, Bazzini DG, Smith SM, Wayne SM. Who smokes in Hollywood? Characteristics of smokers in popular films from 1940 to 1989. Addict Behav. 1998;23(3):395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: a review. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1516–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis RM, Gilpin EA, Loken B, Viswanath K, Wakefield MA, eds. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008:357–428 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sargent JD. Smoking in movies: impact on adolescent smoking. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16(2):345–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in internationally distributed American movies and youth smoking in Germany: a cross-cultural cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/1/e108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362(9380):281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Beach ML. Longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and initiation of smoking by children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Prev Med. 2002;34(5):516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roberts DF, Henriksen L, Christenson PG. Substance Use in Popular Movies and Music. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Worth K, Tanski S, Sargent JD. Trends in Top Box Office Movie Tobacco Use 1996–2004. Washington, DC: American Legacy Foundation; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Sargent JD, et al. Relation between parental restrictions on movies and adolescent use of tobacco and alcohol. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(1):1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Heatherton T, Beach M. Modifying exposure to smoking depicted in movies: a novel approach to preventing adolescent smoking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(7):643–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thompson EM, Gunther AC. Cigarettes and cinema: does parental restriction of R-rated movie viewing reduce adolescent smoking susceptibility? J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):181.e1–181.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, et al. Parental rules and monitoring of children's movie viewing associated with children's risk for smoking and drinking. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1932–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, et al. Effect of parental R-rated movie restriction on adolescent smoking initiation: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of parental movie restriction on teen smoking and drinking in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1722–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychol Rev. 1968;75(2):81–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys' conduct disorder: a reinterpretation. Dev Psychol. 1990;26(5):683–697 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stice E, Barrera M. A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents' substance use and externalizing behaviors. Dev Psychol. 1995;31(2):322–334 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking and Risky Behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007:107–143 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zuckerman M. Behavioral Expressions and Biosocial Bases of Sensation Seeking. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: a theory of genotype → environment effects. Child Dev. 1983;54(2):424–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bardo MT, Donohew RL, Harrington NG. Psychobiology of novelty seeking and drug seeking behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1996;77(1–2):23–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou CP, Li CY, Dwyer JH. Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(3):179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stoolmiller M, Gerrard M, Sargent JD, Worth KA, Gibbons FX. R-rated movie viewing, growth in sensation seeking and alcohol initiation: reciprocal and moderation effects. Prev Sci. 2010;11(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arnett J. Sensation seeking: a new conceptualization and a new scale. Pers Individ Dif. 1994;16(2):289–296 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, Hanewinkel R. Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction. 2010;105(3):506–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):319–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sargent JD, Dalton M. Does parental disapproval of smoking prevent adolescents from becoming established smokers? Pediatrics. 2001;108(6):1256–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Movie smoking exposure and smoking onset: a longitudinal study of mediation processes in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(2):269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Cin SD. Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: a test for mediation through peer affiliations. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(6):952–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling With LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998: 345–385 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Finkel SE. Causal Analysis With Panel Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 5th ed Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model. 1999;6(1):1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 44. McDonald RP, Ho MR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):64–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Insightful Corp Analyzing Data With Missing Values in S-Plus. Seattle, WA: Insightful Corp; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kessler RC, Greenberg DF. Linear Panel Analysis: Models of Quantitative Change. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1981 [Google Scholar]