Background: CpgA is an essential GTPase phosphorylated in vitro by the Ser/Thr kinase PrkC.

Results: CpgA is phosphorylated on Thr-166, and phosphomimetic or phosphoablative replacements of this residue in CpgA modify its GTPase activity.

Conclusion: Phosphorylation of CpgA is probably a key regulatory feature of B. subtilis physiology.

Significance: The regulation of CpgA via phosphorylation may be needed in sporulating B. subtilis cells.

Keywords: Bacillus, GTPase, Phosphorylation, Ribosomes, Serine-Threonine Protein Kinase

Abstract

In Bacillus subtilis, the ribosome-associated GTPase CpgA is crucial for growth and proper morphology and was shown to be phosphorylated in vitro by the Ser/Thr protein kinase PrkC. To further understand the function of the Escherichia coli RsgA ortholog, CpgA, we first demonstrated that its GTPase activity is stimulated by its association with the 30 S ribosomal subunit. Then the role of CpgA phosphorylation was analyzed. A single phosphorylated residue, threonine 166, was identified by mass spectrometry. Phosphoablative replacement of this residue in CpgA induces a decrease of both its affinity for the 30 S ribosomal subunit and its GTPase activity, whereas a phosphomimetic replacement has opposite effects. Furthermore, cells expressing a nonphosphorylatable CpgA protein present the morphological and growth defects similar to those of a cpgA-deleted strain. Altogether, our results suggest that CpgA phosphorylation on Thr-166 could modulate its ribosome-induced GTPase activity. Given the role of PrkC in B. subtilis spore germination, we propose that CpgA phosphorylation is a key regulatory process that is essential for B. subtilis development.

Introduction

GTPases regulate a wide range of cellular processes in bacteria. Many of them, like Era, RbgA, Der, and RsgA, are implicated in the biogenesis of the individual subunits of the ribosome (1–6). To date, the exact function of these GTPases remains unclear. Recently, three independent studies (7–9) have described the role of the GTPase RsgA (formerly YjeQ) from Escherichia coli in ribosome biogenesis. This protein is involved in a late stage of ribosome assembly and enhances the release of the ribosome-binding factor RbfA from the nascent 30 S subunit in a GTP-dependent manner (7). It was also proposed that RsgA acts as a “general checkpoint protein” in the late stage of the 30 S subunit biogenesis because it was also found to inhibit the binding of other initiation factors to the premature 30 S subunit (8). The RsgA homologous protein in Bacillus subtilis is the small GTPase CpgA (formerly YloQ) (10). These two proteins display 38% of sequence identity, and key residues required for their function (8, 10, 11), namely, those of the P-loop and additional GTPase motifs, are fully conserved (supplemental Fig. S1). Depletion or gene inactivation of CpgA induces the same phenotypic features, i.e., impaired growth and alteration of polyribosome profiles with accumulation of the 30 and 50 S subunits at the expense of 70 S mature ribosomes (1, 12). CpgA has also been proposed to participate in cell morphogenesis (12, 13) and in cell wall deposition (14). Indeed, swollen or curly shapes, as well as irregular thickness of the cell wall and accumulation of peptidoglycan precursors, have been observed in CpgA-depleted cells (15).

The cpgA gene is co-transcribed with the prpC and prkC genes, which encode a Ser/Thr phosphatase and a membrane eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinase, respectively. PrpC and PrkC have been shown to be important for biofilm formation and sporulation (16, 17). PrkC contains an extracellular domain with three PASTA motifs (18). PASTA motifs are structurally homologous to the β3α domain present at the C terminus of high molecular weight penicillin-binding proteins that are involved in β-lactam antibiotics binding and peptidoglycan synthesis. It has been shown that PrkC is the key signaling enzyme involved in spore germination in response to peptidoglycan fragments released by cells in the extracellular milieu (19, 20). Several endogenous proteins, including CpgA, have been shown to be phosphorylated in vitro by PrkC and dephosphorylated by PrpC on Ser and Thr residues (14, 15, 18, 19, 21). A role for cpgA, prkC, and prpC locus in the same pathway has thus been proposed (14). However, in contrast to the deletion of either prkC and prpC, which do not display any phenotype, cpgA is necessary for normal growth (16, 22). Furthermore, a phosphoproteomic analysis failed to identify CpgA among ∼80 B. subtilis proteins phosphorylated on Ser, Thr, or Tyr residues (23), and a site directed-mutagenesis approach used in a previous study did not identify the phosphorylation site(s) of CpgA (14). Interestingly, E. coli lacks a PrkC homolog, and phosphorylation of the CpgA homolog RsgA has not been reported so far.

In this study, we investigated the role of CpgA phosphorylation. We first observed that, similarly to RsgA activity (1, 24), the GTPase activity of CpgA is enhanced in vitro in the presence of the ribosome, especially the 30 S subunit. Then we demonstrated that the ribosome-triggered GTPase activity of CpgA is itself dependent on the phosphorylation of CpgA. Indeed, after identifying Thr-166 as being the major phosphorylation site of CpgA in the presence of PrkC, we showed that a phosphomimetic CpgA mutant protein displays an enhanced affinity for the 30 S ribosomal subunit, as well as an increased GTPase activity. By contrast, cells expressing a phosphoablative CpgA have morphological and growth defects similar to those observed in cpgA-deleted cells. These data suggest that CpgA cellular function is controlled by phosphorylation, and this regulation probably plays a crucial role in ribosome biogenesis and B. subtilis development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructions of Bacterial Strains

DNA manipulations as well as E. coli and B. subtilis cell transformations were performed following standard procedures (25, 26). Sequencing of PCR-derived DNA fragments in the plasmid constructs was carried out by GATC-Biotech to ensure error-free amplification. Plasmid pOMG360 (pBAD-His6-cpgA) (13) was used as a template for introducing point mutations into the cpgA gene by PCR to generate the CpgA(K177A), CpgA(T166A), and CpgA(T166D) modified proteins (27). For recombinant polyhistidine-tagged CpgA protein expression, the plasmids pOMG360, pOMG360-cpgA(K177A), pOMG360-cpgA(T166A), and pOMG360-cpgA(T166D) were used to transform E. coli DH5α strain. The catalytic domain of PrkC (PrkCc) was produced from the E. coli strain DH5α containing the pOMG313 plasmid (16). Expression of all proteins was induced with l-arabinose 0.1%, and proteins were purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin as previously described (13). The strain deleted for the cpgA gene (SG229) was constructed by transformation of the WT B. subtilis 168 strain with the DNA from the EB1256 strain (12). B. subtilis strains expressing CpgA proteins with point mutations were constructed by four-partner PCR amplification. The pOMG360 and derived plasmids were used to amplify the modified cpgA genes, and the flanking sequences of cpgA (prkC and rpe genes) were amplified from the chromosomal DNA by PCR with two pairs of primers containing overlapping regions. A global PCR using the three above described fragments and a fragment containing the kanamycin resistance gene were then used to amplify the whole sequence prkC-cpgA-kan-rpe, and the resulting DNA was used to transform the SG229 strain to generate the strains SG226, SG227, SG228, and SG249. All the B. subtilis strains used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | Laboratory stock |

| SG229 | trpC2, cpgA::spec | This work |

| SG228 | trpC2, kan | This work |

| SG226 | trpC2, cpgA (K177A), kan | This work |

| SG227 | trpC2, cpgA (T166A), kan | This work |

| SG249 | trpC2, cpgA (T166D), kan | This work |

General Growth Conditions

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was routinely used for bacterial growth at 37 °C. When necessary, the medium was supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and spectinomycin at 150 μg/ml and kanamycin at 10 μg/ml for B. subtilis).

GTPase Activity Assays

Variable concentrations of CpgA were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C with 0.4 mm of [γ-32P]GTP (1 μCi) in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 30 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 4 mm MgCl2, 100 mm NaCl, and 10 mm KCl. Variable amounts of 70 S ribosome or 50 or 30 S subunits were added to the reaction mix as specified in the experiment. The reaction was stopped by cold shock at 4 °C. 1 μl of each reaction mixture was analyzed by thin layer chromatography using PEI-cellulose F plates from Merck. The plates were then dried and exposed to autoradiography.

In Vitro Phosphorylation Assays

3 μg of CpgA were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C with 0.5 μg of PrkCc in a 15-μl reaction mixture containing 10 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 5 mm MgCl2, 3 μg of myelin basic protein that was shown to stimulate PrkC-mediated phosphorylation (16), and 1 mm [γ-32P]ATP (1 μCi). The phosphorylation reaction was stopped by adding 5× SDS sample buffer to the reaction mixtures before SDS-PAGE analysis. The gels were then dried and exposed to autoradiography.

Phosphoamino Acid Analysis

To characterize the phosphorylated amino acid residues, protein samples were first subjected to SDS-PAGE and then electroblotted onto an Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Phosphorylated proteins bound to the membrane were detected by autoradiography. The 32P-labeled protein bands were excised individually from the Immobilon blot, wetted in methanol, rinsed in water, and finally hydrolyzed in 6 m HCl at 110 °C for 1 h. The acid-stable amino acids thus liberated were separated by TLC with electrophoresis in the first dimension at pH 1.9 (800 V h) in 7.8% acetic acid and 2.4% formic acid, followed by ascending chromatography in the second dimension in 2-methyl-propanol:formic acid:water (8:3:4 v/v/v). After migration, radioactive amino acids were detected by autoradiography. Authentic phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine were run in parallel and visualized by staining with 0.05% ninhydrin in acetone.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Purified CpgA was phosphorylated in vitro by PrkCc as described above with 5 mm cold ATP. Subsequent mass spectrometry analysis using nanoLC/nanospray/tandem mass spectrometry were performed as described in Ref. 28.

Ribosome Purification and Preparation of 30 and 50 S Subunits

Highly purified ribosomes were prepared from B. subtilis (strain168) essentially as described by Daigle and Brown (1).

Separation of the 70 S Ribosome into 30 and 50 S Subunits

This was achieved as previously described (29). Quantitation of subunits was done by absorbance at 260 nm (an A260 of 1 is equivalent to 69 pmol of 30 S ribosomal subunit or to 34.5 pmol of 50 S subunit).

His6-CpgA Association with 30 and 50 S Subunits (Co-sedimentation Assays)

A mixture of 21 pmol of B. subtilis 70 S ribosome (A260 = 0.9) and 84 pmol of His6-CpgA was preincubated for 15 min in the presence of 100 μm of the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GMP-PNP3 that was shown to strongly enhance the interaction between GTPases and ribosomal subunits; in particular it stimulates the interaction between RsgA and the 30 S ribosomal subunit (1, 24, 30). Then the sample was sedimented through a 5 to 20% (w/v) sucrose gradient in standard buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mm magnesium acetate, 30 mm KCl) at 200,000 × g at 4 °C for 190 min in a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman). The resulting fractions of 30 and 50 S subunits were pooled and analyzed as described above (absorbance at 260 nm, precipitation by 10% TCA and 0.02% deoxycholate), and immunoblotting was performed with an His probe-HRP (Thermo Scientific) (29).

Fluorescein Labeling of Proteins

2 mm fluorescein-5-EX, succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen) was prepared in anhydrous Me2SO. 4.5 μm of 70 S ribosome in 50 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mm KCl, and 30 mm MgCl2 were mixed with 0.1 mm dye and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C with continuous gentle agitation. Labeled ribosomes were separated from free fluorescein compounds by gel filtration, loaded onto a 5 to 20% (w/v) sucrose gradient in standard buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mm magnesium acetate, 30 mm KCl), and sedimented at 200 000 × g at 4 °C for 190 min in a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman). Ribosome concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm (an A260 of 1 corresponds to 34.5 and 69 pmol of 50 and 30 S, respectively), and fluorescein incorporation was calculated by measuring fluorescence (λ excitation: 494 nm, λ emission: 512 nm), with fluorescein (fluorescein sodium salt; Fluka) as a standard. Labeled 30 and 50 S subunits incorporated 2–3 fluorescein molecules/subunit. The fluorescence measurements were made using a PTI (Photon Technology International MD5020) spectrofluorimeter operated in the photon counting mode. The samples were stirred continuously at 30 °C in 30 mm Tris-H2SO4, pH 7.5, 10 mm magnesium acetate, 60 mm NH4Cl, 60 mm KCl, 2.5 mm DTT, 0.3 mm EDTA, and 15% glycerol.

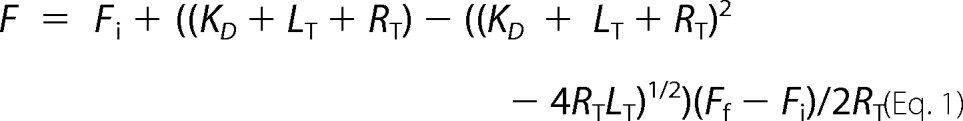

Calculation of Dissociation Constants (KD)

The KD values for the binding of CpgA to fluorescein-labeled 30 S ribosomes were obtained using the following equation,

|

where F is the fluorescence value, Fi is the initial fluorescence, Ff is the final fluorescence, LT is the total concentration of CpgA or its derivatives, and RT is the total concentration of 30 S ribosomes. Fits of the graphs were generated using GraFit5 software.

Microscopy

The cells were observed in differential interference contrast with an upright Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope connected with a Hamamatsu ORCA ER camera at 63× NA 0.75 objective as described in Ref. 31.

Western Blot

The cells were grown at 37 °C in 20 ml of LB medium to A600 = 0.7 and then centrifuged for 10 min at 8000 rpm at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1/10th of the volume of lysis buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm PMSF, 25 units/ml benzonase, and 10 mg/ml lyzozyme. The extracts were incubated for 10 min on ice and then heated at 100 °C for 10 min. The samples were run on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. The membrane was blocked with PBS solution containing 5% milk powder (w/v) for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. The membrane was incubated overnight with anti-CpgA antibody used at 1/2000 dilution then with the secondary antibody, a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Thermo Scientific) antibody, used at 1/2000 dilution for 1 h. After three washes, the blot membrane was incubated with ECL reagents (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), exposed to CL-Xposure films (Thermo Scientific) and developed.

RESULTS

GTPase Activity of CpgA Is Increased upon Interaction with Ribosomes

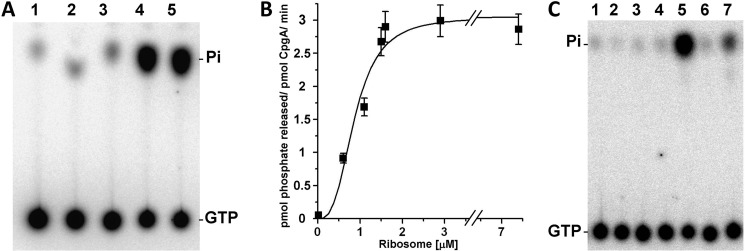

The GTPase activity of the CpgA ortholog RsgA from E. coli is strongly stimulated by the 30 S subunit of the ribosome (1). This observation prompted us to determine whether CpgA GTPase activity was similarly stimulated by the ribosome. For that, the hydrolysis of [γ-32P]GTP by purified His6-CpgA was measured by autoradiography after separation by TLC. In the absence of the ribosome, the GTPase activity of CpgA was low (Fig. 1, A, lane 3, and B) and equivalent to 0.05 pmol of Pi released/min/pmol of CpgA. However, it was strongly stimulated (∼50-fold) in the presence of the mature ribosome 70 S (Fig. 1, A, lanes 4 and 5, and B). Using purified ribosome subunits, we further observed that the addition of the 30 S subunit (Fig. 1C, lane 7) was able to stimulate CpgA activity. By contrast, no activation was observed in the presence of the 50 S subunit (Fig. 1C, lane 6). These results indicate that the GTPase activity of CpgA, similar to that of RsgA, is specifically stimulated by the 30 S ribosomal subunit.

FIGURE 1.

Stimulation of the GTPase activity of CpgA by the ribosome. A, the hydrolysis of [γ-32P]GTP was measured in the presence of CpgA and increasing amounts of ribosome as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Lane 1, without CpgA and without ribosome; lane 2, 2 μm of ribosome alone; lanes 3–5, 5 μm of CpgA incubated in the presence of 0, 0.25, and 0.5 μm of ribosome, respectively. B, the hydrolysis of [γ-32P]GTP was measured after 15 min of incubation at 37 °C in the presence of 5 μm of CpgA and increasing amounts of 70 S ribosome and 0.4 mm of [γ-32P]GTP. The graph represents the specific activity of CpgA (expressed in pmol of Pi released/pmol of CpgA/min) as a function of the ribosome concentration in the reaction mixture. The values correspond to the average of the data from three independent experiments. C, the hydrolysis of [γ-32P]GTP was measured in the presence of 5 μm of CpgA and of 0.1 μm of different ribosome subunits. Lane 1, whole ribosome (70 S) alone; lane 2, 50 S subunit alone; lane 3, 30 S subunit alone; lane 4, without ribosome and without CpgA, lane 5, CpgA and 70 S ribosome; lane 6, CpgA and 50 S subunit; lane 7, CpgA and 30 S subunit.

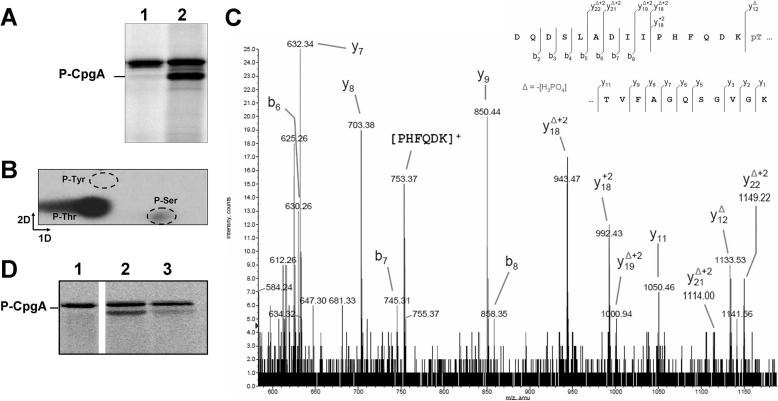

CpgA Is Phosphorylated in Vitro by PrkC on Thr-166

To identify the phosphorylated residue(s) and to analyze the role of the phosphorylation of CpgA by PrkC, we first tested the phosphorylation of the purified His6-CpgA in the presence of the catalytic domain of PrkC (His6-PrkCc) and radioactive ATP. Phosphorylation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and by autoradiography as shown in Fig. 2A. The presence of two radioactive signals indicated that PrkCc was autophosphorylated (17) and was able to phosphorylate CpgA as previously observed. To characterize the nature of the phosphorylated amino acids, acidic hydrolysis of phosphorylated CpgA (P-CpgA) was performed, and the liberated acid-stable phospho-amino acids were separated by two-dimensional chromatography (Fig. 2B). The major radioactive signal corresponded to P-Thr residue(s), whereas a weak signal was correlated to P-Ser residue(s). Further analysis by mass spectrometry after chymotryptic digestion showed that Thr-166 is a major phosphorylation site of CpgA (Fig. 2C). To determine whether Thr-166 was the unique phosphorylation site on CpgA, it was substituted for a nonphosphorylatable Ala residue. We then checked whether the resulting protein CpgA(T166A) was still phosphorylatable by PrkCc (Fig. 2D). As observed in the lane 3 of Fig. 2D, a faint residual radioactive signal was still detected. However mass spectrometric analysis of CpgA(T166A) protein, having been incubated in the presence of His6-PrkCc and ATP, did not detect any additional phosphorylated residue. The weak phosphorylation signal of CpgA(T166A) possibly correlates to the weak P-Ser phosphorylation detected in Fig. 2B. Therefore the Thr-166 residue is the major phosphorylation site of CpgA in vitro. Attempts to detect phosphorylated CpgA in vivo from a B. subtilis crude extract were made without success. Using anti-P-Thr antibodies, phosphorylation profiling revealed a very faint signal of phosphorylation for an overproduced GFP-CpgA fusion protein purified from B. subtilis crude extract (data not shown). However, analysis by mass spectrometry did not reveal a peak corresponding to a phosphorylated peptide of purified GFP-CpgA, suggesting that the protein was insufficiently phosphorylated to be detected by this method. CpgA is presumably not always phosphorylated throughout the bacterial cell cycle and therefore difficult to assess in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of the phosphorylation site of CpgA. A, the CpgA protein was phosphorylated by PrkC as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Myelin basic protein, PrkCc, and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated in the absence (lane 1) or in the presence (lane 2) of 3 μg of purified CpgA. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The upper band corresponds to the autophosphorylated PrkCc. B, the CpgA protein was phosphorylated and hydrolyzed. The phosphorylated amino acid residues were separated by electrophoresis in the first dimension and ascending chromatography in the second dimension. The positions of the standards (ninhydrin visualization of nonradioactive phosphoamino acids) are shown on the figure. C, identification of Thr-166 as the PrkC phosphorylated residue in CpgA by mass spectrometry. MS/MS spectrum of the doubly charged ion [M+2H]2+ at m/z 985.4 of a peptide (160–186). Location of the phosphate group on Thr-166 was shown by observation of the “y” C-terminal daughter ion series. Starting from the C terminus residue, all y ions lose the phosphoric acid (−98 Da) after the Thr-166-phosphorylated residue. D, phosphorylation of the CpgA(T166A) mutant. Myelin basic protein, PrkCc, and [γ-32P]ATP were incubated in the absence of CpgA (lane 1), in the presence of 3 μg of CpgA (lane 2), and in the presence of 3 μg of CpgA(T166A) (lane 3). The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The upper radioactive band visualized in all lanes is the autophosphorylated PrkCc protein.

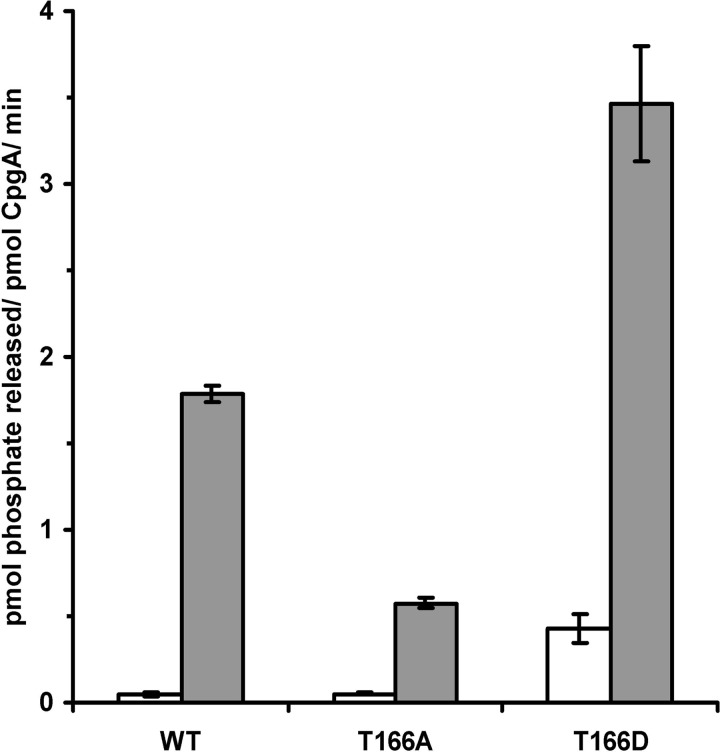

P-mimetic or P-ablative Replacement of Thr-166 Modifies GTPase Activity of CpgA

In a first attempt to understand the role of the phosphorylation of CpgA by PrkC, we tested whether Thr-166 phosphorylation affects the GTPase activity of CpgA. Because the level of phosphorylation of purified CpgA by PrkC was weak in our experimental conditions (only a few percent), we decided to use phosphomimetic and phosphoablative replacements. We thus carried out site-directed mutagenesis to produce different forms of CpgA with Thr-166 being substituted for an Ala (CpgA(T166A)) or Asp (CpgA(T166D)) residue, that is, either a phosphoablative version or a constitutively phosphorylated one. The stability of CpgA mutated forms was checked by limited proteolysis and was similar to that of the wild-type protein (data not shown). Then purified wild-type CpgA and derivatives were used in radioactive GTPase activity assays in the presence or in the absence of ribosome as described above. Relative GTPase activities are shown in the histogram presented in Fig. 3. As previously mentioned (Fig. 1), the GTPase activity of wild-type CpgA was highly stimulated by the 70 S mature ribosome. First, we compared the GTPase activity of the three CpgA derivates in the absence of ribosome. Wild-type CpgA and CpgA(T166A) were found to be poorly active (0.05 pmol of Pi released/min/pmol of CpgA). By contrast, a 9-fold higher GTPase activity was detected with the P-mimetic protein CpgA(T166D) compared with that of the wild-type protein. This result suggests that the P-mimetic replacement of the Thr-166 of CpgA enhances its GTPase activity. Then in the presence of 70 S ribosome, we observed that the GTPase activity of all CpgA derivates was stimulated but at different levels. Under our experimental conditions, the GTPase activity of the P-mimetic mutant was 2-fold higher than that of the wild-type CpgA, whereas the activity of the P-ablative mutant was ∼3-fold lower than that of the wild-type CpgA. The replacement of Thr-166 by an Ala residue not only prevented phosphorylation but also significantly decreased its GTPase activity with a clear decrease of the stimulation by the 70 S ribosome. Therefore, the high GTPase activity of phosphomimetic CpgA(T166D), even in the absence of the ribosome, strongly suggests that CpgA phosphorylation stimulates its GTPase activity.

FIGURE 3.

GTPase activity of modified CpgA proteins. The GTPase activity of CpgA was measured after 15 min as described under “Experimental Procedures” with 5 μm of each CpgA protein without ribosome (in white) or with 2.5 μm of 70 S ribosome (in gray). The histogram represents the specific activity of each protein, CpgA(WT), CpgA(T166A), and CpgA(T166D), expressed in pmol of Pi released/pmol of enzyme/min. The values correspond to the averages of data from at least three independent experiments.

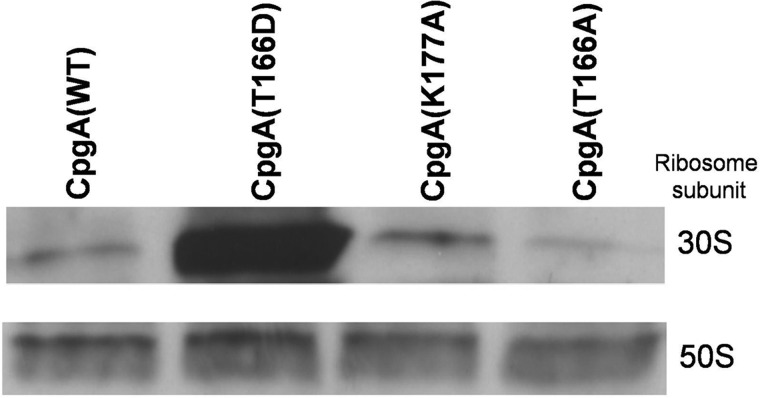

P-mimetic Replacement of Thr-166 Enhances CpgA Affinity for 30 S Ribosomal Subunit

We had previously observed that the GTPase activity of CpgA was enhanced upon interaction with ribosomes. We therefore analyzed whether or not phosphorylation of Thr-166 could also affect CpgA ability to interact with either the 30 or 50 S subunits of the ribosome by co-sedimentation assays (Fig. 4). The WT and variant forms of His6-CpgA were preincubated with 70 S ribosome in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GMP-PNP, because RsgA interaction with ribosome was shown to be nucleotide-dependent (1, 24). The mixture was incubated under dissociation conditions into 30 and 50 S ribosomal subunits, then separated by ultracentrifugation along a sucrose gradient, and revealed by immunoblotting with an His Probe-HRP. As a negative control, we replaced the invariant catalytic lysine in the P-loop (Walker A) of CpgA (supplemental Fig. S1) by an alanine to produce CpgA(K177A) (32), thus inactivating its GTPase activity. All of the purified CpgA proteins associated poorly with the 50 S subunit of the ribosome whatever the mutation considered, whereas the binding with the 30 S subunit was strongly increased with the T166D mutant compared with wild-type CpgA. By contrast, the binding with the 30 S subunit was weakly inhibited by the T166A mutation. We also attempted to directly monitor the effect of the phosphorylation of CpgA on its activity and on its binding to the ribosome by using a preparation of purified CpgA phosphorylated by PrkC. However, the experiments were not conclusive because of a very limited phosphorylation ratio of CpgA in vitro (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggest that the P-mimetic replacement of CpgA increases its affinity for the 30 S subunit of the ribosome. To confirm this result, we determined the kinetic parameters of this interaction by another approach, i.e., by spectrofluorimetric detection of labeled ribosomes in the presence of GMP-PNP (Table 2). We observed that the affinity of CpgA for the 30 S ribosomal subunit was weakly affected by a mutation in the P-loop motif (CpgA(K177A)) compared with wild-type CpgA. However, the mutation of the Thr-166 residue modified the affinity of CpgA for the ribosome. Indeed, we measured a 3-fold lower affinity for the P-ablative CpgA(T166A) mutant. Importantly, in these experimental conditions, we detected a 2-fold higher affinity for the ribosome in the case of the P-mimetic mutant CpgA(T166D) compared with the native protein. These results suggest that CpgA phosphorylation on Thr-166 not only is important for its GTPase activity but also enhances its interaction with the 30 S subunit of the ribosome.

FIGURE 4.

Associations of CpgA proteins to the 30 and 50 S subunits in vitro. 21 pmol of B. subtilis 70 S ribosome (A260 = 0.9) were preincubated with 84 pmol of each His6-CpgA protein and sedimented through a 5 to 20% (w/v) sucrose gradient at 200,000 × g at 4 °C for 190 min. The resulting fractions containing the ribosome subunits/protein complexes were pooled and analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures” and separated by SDS-PAGE. His6-CpgA was immunochemically detected with a His HRP-labeled probe.

TABLE 2.

Dissociation constants of CpgA binding to the 30 S subunit of the ribosome determined by spectrofluorimetry

| Protein | KDa |

|---|---|

| nm | |

| CpgA(WT) | 3.4 ± 0.8 |

| CpgA(K177A) | 5.4 ± 2.3 |

| CpgA(T166A) | 9 ± 2.6 |

| CpgA(T166D) | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

a All of the values correspond to the averages of data from at least three independent experiments.

Phenotypes Associated with CpgA Modifications

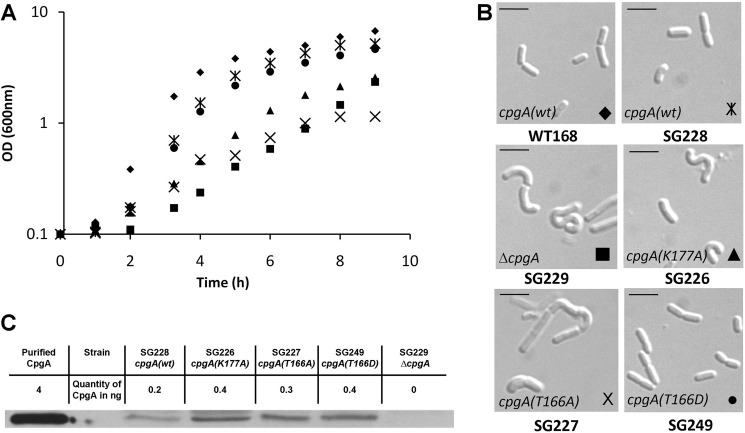

Our in vitro experiments demonstrate that phosphorylation of Thr-166 is important for the function of CpgA. To assess the role of CpgA phosphorylation in vivo, we constructed B. subtilis strains expressing the CpgA derivatives described above. Because the cpgA gene is required for normal growth and shape (12, 13), we monitored cell growth and observed cell morphology of the CpgA mutant strains. As a positive control, the strain containing a native copy of cpgA plus the kanamycin-resistant marker grew at the same rate as the wild-type 168 strain (Fig. 5A) and displayed no morphological defects (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the strain deleted for cpgA presented all of the expected altered phenotypes. The strain expressing CpgA(T166D) grew as well as the wild-type strain and presented normally shaped cells, whereas the strains expressing CpgA(K177A) or CpgA(T166A) grew more slowly and exhibited a curly morphology (Fig. 5, A and B). Importantly, CpgA levels were nearly identical in all strains (Fig. 5C), indicating that these phenotypes were not simply linked to differences in the expression and stability of the CpgA variants but rather due to the effect of these mutations on CpgA activity. Despite a slightly lower expression level, no aberrant phenotype was observed in the strain expressing the wild-type CpgA protein, suggesting that the level of CpgA (WT) was sufficient for its function in vivo. The phenotypes observed for the different strains could then be assigned to the mutation on the cpgA gene. Altogether, these results indicate that the phenotypes observed for either the deleted strain or the mutated strains, expressing inactive or nonphosphorylatable proteins, are linked to the loss of their GTPase activity. Because the strain expressing a GTPase active P-mimetic protein had no detectable aberrant phenotype, we conclude that the phosphorylation of CpgA on Thr-166 is required for B. subtilis cell integrity.

FIGURE 5.

Morphological effects of the modification of the GTPase activity of CpgA. Single mutations have been introduced at the cpgA locus, and the phenotypes of the resulting strains have been analyzed. A, growth curves of the cpgA mutated strains in LB medium: WT168 (♦), SG228 (cpgA(wt), X with vertical line), SG229 (ΔcpgA, ■), SG226 (cpgA(K177A), ▴), SG227 (cpgA(T166A), ×), and SG249 (cpgA(T166D), ●). B, the cell shape of the strains was observed by differential interference contrast microscopy during the growth in LB medium, and the images were taken during the exponential phase of each curve. The scale bars represent 5 μm. C, CpgA and derivative proteins were detected from crude extracts by Western blot using anti-CpgA antibodies and quantified. Lane 1, 4 ng of purified His6-CpgA; lane 2, SG228 (cpgA(wt)); lane 3, SG226 (cpgA(K177A)); lane 4, SG227 (cpgA(T166A)); lane 5, SG249 (cpgA(T166D)); lane 6, SG229 (ΔcpgA).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that CpgA, like the E. coli homolog RsgA, is a GTPase that binds to the 30 S subunit of the ribosome. Analogous to RsgA (7), it can be assumed that CpgA may dissociate RbfA (ribosome binding factor) from the 30 S subunit in a GTP-dependent manner to allow maturation of this subunit during a late stage of ribosome biogenesis. The GTPase activity of CpgA is thus probably important for efficient ribosome maturation and consequently for bacterial growth. In line with this idea, both cpgA from B. subtilis and rsgA from E. coli were first described as essential genes (33), even though their essentiality has been controversial and, in both bacteria, knock-out viable mutants were eventually obtained (12, 24, 34).

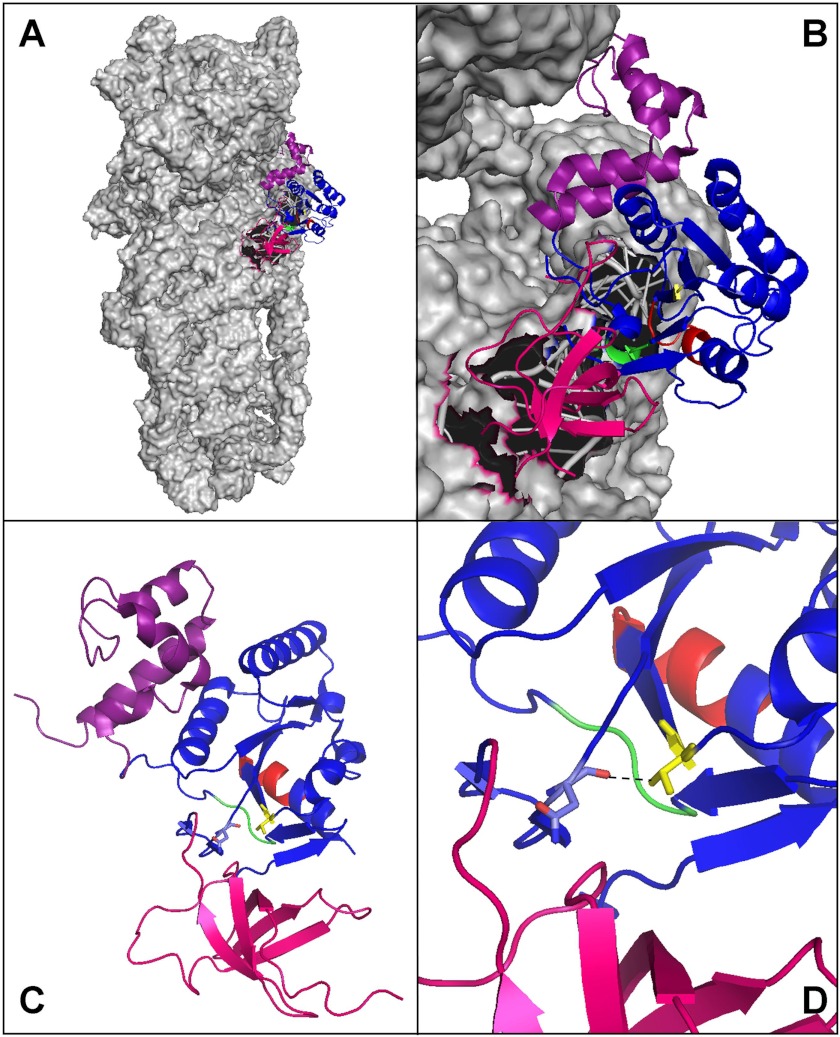

We show that CpgA is phosphorylated by PrkC on Thr-166 and that this phosphorylation likely governs the cellular function of CpgA. Indeed, the replacement of Thr-166 by a nonphosphorylatable Ala decreases not only the GTPase activity of CpgA but also its affinity for the 30 S subunit of the ribosome, whereas the replacement of Thr-166 by a phosphomimetic Asp stimulates both its GTPase activity and its affinity for the 30 S subunit. We thus conclude that phosphorylation of CpgA on Thr-166 modulates its GTPase activity and its interaction with the 30 S subunit of the ribosome. CpgA has a three-domain organization (10). The N-terminal region of CpgA is an oligonucleotide-binding (OB) domain, the central part of the protein is the GTPase domain, and the C-terminal region is an α-helical domain containing a coordinated zinc ion. The phosphorylatable Thr-166 amino acid residue is located within the GTPase domain, at the interface with the OB domain (Fig. 6). The deletion of the OB domain in RsgA resulted in the loss of stimulation of the GTPase activity by the ribosome (1). Structural studies of RsgA, whose structure superimposes with that of CpgA, were carried out in the presence of nucleotides and the 30 S subunit (8, 9). The authors characterized the interactions between the 30 S subunit and the OB domain. They observed conformational changes between the free RsgA and RsgA bound to GDP and the 30 S subunit that mainly occur in the N- and C-terminal domains. In particular, the OB domain shows very pronounced conformational changes with lateral and rotational movements upon binding to 30 S subunit. All of these conformational modifications were proposed to be important for the binding of RsgA to the 30 S subunit, which is modulated by the nucleotide nature and occupancy of the GTPase domain. We can speculate that the phosphorylation of Thr-166, given its interfacial positioning between the GTPase and C-terminal domains, could relay these conformational changes and thus enhance both the GTPase activity of CpgA and its interaction with the 30 S subunit (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Structure of RsgA and CpgA showing localization of the Thr-166 residue at the interface of the GTPase domain and the OB domain. RsgA and CpgA are structurally similar and have a three-domain organization: the N-terminal OB domain (in pink), the GTPase domain (in blue), and the C terminus domain (in purple). The P-loop is colored in red, the GTPase motif DXXG is in green, and the 166 residue is colored in yellow. A, cartoon representation of the E. coli RsgA bound to the 30 S ribosomal subunit (shown in space-filling model; Protein Data Bank entry 2YKR). B, zoom on the interaction between RsgA and the 30 S subunit. C, cartoon representation of the structure of B. subtilis CpgA (Protein Data Bank 1T9H). The phosphorylatable Thr-166 residue is located at the interface of the GTPase domain and the OB domain. The amino acids Thr-166 and Asn-77 are displayed as a stick model. D, zoom on the region containing the Thr-166 and showing the proximity with the Asn-77 residue. This figure was drawn using PyMOL software.

T166A replacement within CpgA leads to the same phenotype as the absence of CpgA or its inactivation by a K177A substitution, whereas T166D replacement within CpgA has no phenotypic effect. The co-transcription of the three genes cpgA, prkC, and prpC in B. subtilis suggests that despite the weak evidence about CpgA phosphorylation in vivo, they probably regulate the same functional pathway (14). However, the mutation of the Thr-166, found to be the phosphorylation site of CpgA in vitro, appears to affect normal vegetative growth, whereas prkC can be deleted without any effect during logarithmic growth or early stationary phase (16, 22). This apparent paradox has already been discussed (14), and it was proposed that either the PrkC function is redundant or the phosphorylation of CpgA does not affect bacterial growth, but in the light of our data, we can now exclude this proposal. Genome sequence analysis shows that B. subtilis possesses at least three other potential STKP: YbdM (or PrkD) that is similar to the kinase domain of PrkC (16), YxaL, and YabT (21). We can speculate that one of these putative kinases or another yet unidentified protein kinase that does not belong to the Hanks-type serine/threonine protein kinase could also phosphorylate CpgA on Thr-166 in vivo (or on another residue that would lead to a similar functional consequence). Although less likely, an alternative explanation is that the absence of CpgA phosphorylation could be bypassed in a prkC-deficient strain by a compensatory effect because of the absence of phosphorylation of other(s) substrate(s) of PrkC (21, 35).

No gene encoding a PrkC homolog or a Hanks-type Ser/Thr protein kinase has been identified in the E. coli genome. One can argue that such a phospho-mediated regulatory process is unlikely to occur in E. coli. It would thus satisfy other purposes for B. subtilis development but also for related bacteria where a genetic link between the prkC and cpgA exists. However, the phosphorylated Thr-166 residue is not conserved in the sequence of CpgA homologs from other species (supplemental Fig. S1), even in the sporulating ones. Instead of being a rule, the conservation of phosphorylation sites in orthologous protein is rather an exceptional feature. For example, many glycolytic enzymes were found to be phosphorylated in E. coli (36) or B. subtilis (23) phosphoproteomes and in other bacteria. For some of these glycolytic phosphoproteins, like the enolase (eno), the phosphotransacetylase (pta) or the phosphoglucose isomerase (pgi), their phosphorylation sites have been determined in multiple species, and they diverge from one species to another. We have also analyzed whether prkC, prpC, and cpgA/rsgA are often genetically linked and observed that these three genes are close in many species, namely in lactobacilli, bacilli, clostridi, and in the cell wall-free bacteria mycoplasma (supplemental Fig. S2). This observation suggests that a regulation of CpgA activity by phosphorylation is not restricted to B. subtilis but is probably extended to all bacteria in which the prkC, prpC, and the cpgA/rsgA genes are genetically linked. Interestingly, the relationship between PrkC and CpgA does not seem to be correlated with the capacity of the bacteria to sporulate.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that PrkC was able to sense peptidoglycan fragments released by growing cells during the exit of B. subtilis spores from dormancy (19, 20, 35). In this context, PrkC acts as a bacterial receptor controlling a phosphorylation cascade, allowing cells to sense and adapt to their environment. The activation via phosphorylation by PrkC of substrates like CpgA, involved in ribosome maturation, and EF-G, involved in mRNA and tRNA translocation (37), could assist germination when conditions become more favorable. In addition, dormant spores from B. megaterium have been shown to contain large amounts of mRNA and ribosomes (38) probably necessary for essential processes underlying the exit from dormancy. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that germinating spores need to quickly reactivate essential processes like translation and increase the activity and/or the affinity of ribosome maturation factors like CpgA via PrkC phosphorylation. Challenging as it may be, this hypothesis represents an attractive working model to decipher the biological function of CpgA phosphorylation in B. subtilis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Common Center for Microanalysis of Proteins of the Institute of Biology and Chemistry of Proteins for expertise in mass spectrometry and B. Hermant (Institut de Biologie Structurale) for the ribosome preparations. We also thank S. Seror for the kind gift of the plasmids pOMG360 and pOMG313 and B. Khadaroo for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the CNRS, Agence Nationale de la Recherche “P-loop proteins” Grant ANR-08-BLAN-0143, and the Universities of Aix-Marseille, Grenoble and Lyon.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- GMP-PNP

- 5′-guanylylimidodiphosphate

- OB

- oligonucleotide-binding.

REFERENCES

- 1. Daigle D. M., Brown E. D. (2004) Studies of the interaction of Escherichia coli YjeQ with the ribosome in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1381–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hwang J., Inouye M. (2006) The tandem GTPase, Der, is essential for the biogenesis of 50S ribosomal subunits in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1660–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inoue K., Alsina J., Chen J., Inouye M. (2003) Suppression of defective ribosome assembly in a rbfA deletion mutant by overexpression of Era, an essential GTPase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsuo Y., Morimoto T., Kuwano M., Loh P. C., Oshima T., Ogasawara N. (2006) The GTP-binding protein YlqF participates in the late step of 50 S ribosomal subunit assembly in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8110–8117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shajani Z., Sykes M. T., Williamson J. R. (2011) Assembly of bacterial ribosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 501–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schaefer L., Uicker W. C., Wicker-Planquart C., Foucher A. E., Jault J. M., Britton R. A. (2006) Multiple GTPases participate in the assembly of the large ribosomal subunit in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 8252–8258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goto S., Kato S., Kimura T., Muto A., Himeno H. (2011) RsgA releases RbfA from 30S ribosome during a late stage of ribosome biosynthesis. EMBO J. 30, 104–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo Q., Yuan Y., Xu Y., Feng B., Liu L., Chen K., Sun M., Yang Z., Lei J., Gao N. (2011) Structural basis for the function of a small GTPase RsgA on the 30S ribosomal subunit maturation revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13100–13105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jomaa A., Stewart G., Mears J. A., Kireeva I., Brown E. D., Ortega J. (2011) Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the 30S subunit in complex with the YjeQ biogenesis factor. RNA 17, 2026–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levdikov V. M., Blagova E. V., Brannigan J. A., Cladière L., Antson A. A., Isupov M. N., Séror S. J., Wilkinson A. J. (2004) The crystal structure of YloQ, a circularly permuted GTPase essential for Bacillus subtilis viability. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 767–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shin D. H., Lou Y., Jancarik J., Yokota H., Kim R., Kim S. H. (2004) Crystal structure of YjeQ from Thermotoga maritima contains a circularly permuted GTPase domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13198–13203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell T. L., Daigle D. M., Brown E. D. (2005) Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis GTPase YloQ and its role in ribosome function. Biochem. J. 389, 843–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cladière L., Hamze K., Madec E., Levdikov V. M., Wilkinson A. J., Holland I. B., Séror S. J. (2006) The GTPase, CpgA(YloQ), a putative translation factor, is implicated in morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 275, 409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Absalon C., Obuchowski M., Madec E., Delattre D., Holland I. B., Séror S. J. (2009) CpgA, EF-Tu and the stressosome protein YezB are substrates of the Ser/Thr kinase/phosphatase couple, PrkC/PrpC, in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 155, 932–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Absalon C., Hamze K., Blanot D., Frehel C., Carballido-Lopez R., Holland B. I., van Heijenoort J., Séror S. J. (2008) The GTPase CpgA is implicated in the deposition of the peptidoglycan sacculus in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3786–3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madec E., Laszkiewicz A., Iwanicki A., Obuchowski M., Séror S. (2002) Characterization of a membrane-linked Ser/Thr protein kinase in Bacillus subtilis, implicated in developmental processes. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 571–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madec E., Stensballe A., Kjellström S., Cladière L., Obuchowski M., Jensen O. N., Séror S. J. (2003) Mass spectrometry and site-directed mutagenesis identify several autophosphorylated residues required for the activity of PrkC, a Ser/Thr kinase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 330, 459–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeats C., Finn R. D., Bateman A. (2002) The PASTA domain. A β-lactam-binding domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah I. M., Laaberki M. H., Popham D. L., Dworkin J. (2008) A eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinase signals bacteria to exit dormancy in response to peptidoglycan fragments. Cell 135, 486–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Squeglia F., Marchetti R., Ruggiero A., Lanzetta R., Marasco D., Dworkin J., Petoukhov M., Molinaro A., Berisio R., Silipo A. (2011) Chemical basis of peptidoglycan discrimination by PrkC, a key kinase involved in bacterial resuscitation from dormancy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20676–20679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pietack N., Becher D., Schmidl S. R., Saier M. H., Hecker M., Commichau F. M., Stülke J. (2010) In vitro phosphorylation of key metabolic enzymes from Bacillus subtilis. PrkC phosphorylates enzymes from different branches of basic metabolism. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 129–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaidenko T. A., Kim T. J., Price C. W. (2002) The PrpC serine-threonine phosphatase and PrkC kinase have opposing physiological roles in stationary-phase Bacillus subtilis cells. J. Bacteriol. 184, 6109–6114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Macek B., Mijakovic I., Olsen J. V., Gnad F., Kumar C., Jensen P. R., Mann M. (2007) The serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphoproteome of the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 697–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Himeno H., Hanawa-Suetsugu K., Kimura T., Takagi K., Sugiyama W., Shirata S., Mikami T., Odagiri F., Osanai Y., Watanabe D., Goto S., Kalachnyuk L., Ushida C., Muto A. (2004) A novel GTPase activated by the small subunit of ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5303–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunst F., Rapoport G. (1995) Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2403–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kammann M., Laufs J., Schell J., Gronenborn B. (1989) Rapid insertional mutagenesis of DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fiuza M., Canova M. J., Zanella-Cléon I., Becchi M., Cozzone A. J., Mateos L. M., Kremer L., Gil J. A., Molle V. (2008) From the characterization of the four serine/threonine protein kinases (PknA/B/G/L) of Corynebacterium glutamicum toward the role of PknA and PknB in cell division. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18099–18112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wicker-Planquart C., Foucher A. E., Louwagie M., Britton R. A., Jault J. M. (2008) Interactions of an essential Bacillus subtilis GTPase, YsxC, with ribosomes. J. Bacteriol. 190, 681–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Achila D., Gulati M., Jain N., Britton R. A. (2012) Biochemical characterization of ribosome assembly GTPase RbgA in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 8417–8423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pompeo F., Luciano J., Brochier-Armanet C., Galinier A. (2011) The GTPase function of YvcJ and its subcellular relocalization are dependent on growth conditions in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 156–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saraste M., Sibbald P. R., Wittinghofer A. (1990) The P-loop. A common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 15, 430–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arigoni F., Talabot F., Peitsch M., Edgerton M. D., Meldrum E., Allet E., Fish R., Jamotte T., Curchod M. L., Loferer H. (1998) A genome-based approach for the identification of essential bacterial genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hunt A., Rawlins J. P., Thomaides H. B., Errington J. (2006) Functional analysis of 11 putative essential genes in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 152, 2895–2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dworkin J., Shah I. M. (2010) Exit from dormancy in microbial organisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 890–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Macek B., Gnad F., Soufi B., Kumar C., Olsen J. V., Mijakovic I., Mann M. (2008) Phosphoproteome analysis of E. coli reveals evolutionary conservation of bacterial Ser/Thr/Tyr phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Savelsbergh A., Katunin V. I., Mohr D., Peske F., Rodnina M. V., Wintermeyer W. (2003) An elongation factor G-induced ribosome rearrangement precedes tRNA-mRNA translocation. Mol. Cell 11, 1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chambon P., Deutscher M. P., Kornberg A. (1968) Biochemical studies of bacterial sporulation and germination. X. Ribosomes and nucleic acids of vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5110–5116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]