Background: Activity of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase Sir2 is stimulated by isonicotinamide (INAM) in vitro.

Results: INAM unexpectedly increased the intracellular NAD+ concentration when added to growth medium.

Conclusion: INAM-induced increases in NAD+ concentration require significant contributions from the NAD+ and nicotinamide riboside salvage pathways.

Significance: INAM appears to promote NAD+ homeostasis, which favors Sir2-dependent processes.

Keywords: Aging, Histone Deacetylase, NAD, Sirtuins, Yeast, Sir2, Isonicotinamide, Silencing

Abstract

Sirtuins are an evolutionarily conserved family of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases that function in the regulation of gene transcription, cellular metabolism, and aging. Their activity requires the maintenance of an adequate intracellular NAD+ concentration through the combined action of NAD+ biosynthesis and salvage pathways. Nicotinamide (NAM) is a key NAD+ precursor that is also a byproduct and feedback inhibitor of the deacetylation reaction. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the nicotinamidase Pnc1 converts NAM to nicotinic acid (NA), which is then used as a substrate by the NAD+ salvage pathway enzyme NA phosphoribosyltransferase (Npt1). Isonicotinamide (INAM) is an isostere of NAM that stimulates yeast Sir2 deacetylase activity in vitro by alleviating the NAM inhibition. In this study, we determined that INAM stimulates Sir2 through an additional mechanism in vivo, which involves elevation of the intracellular NAD+ concentration. INAM enhanced normal silencing at the rDNA locus but only partially suppressed the silencing defects of an npt1Δ mutant. Yeast cells grown in media lacking NA had a short replicative life span, which was extended by INAM in a SIR2-dependent manner and correlated with increased NAD+. The INAM-induced increase in NAD+ was strongly dependent on Pnc1 and Npt1, suggesting that INAM increases flux through the NAD+ salvage pathway. Part of this effect was mediated by the NR salvage pathways, which generate NAM as a product and require Pnc1 to produce NAD+. We also provide evidence suggesting that INAM influences the expression of multiple NAD+ biosynthesis and salvage pathways to promote homeostasis during stationary phase.

Introduction

The sirtuins make up a large family of phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases (1, 2). Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sir2 is the founding member and functions as a histone deacetylase in the silencing of transcription at the silent mating-type loci (3), telomeres (4), and the rDNA locus (5, 6). Sir2 is also required for maintaining the replicative life span (RLS)2 of this organism, such that deleting SIR2 shortens RLS, and overexpression extends RLS (7). Specific sirtuins in more complex eukaryotes such as Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, and mice regulate a large number of cellular processes linked to age-related conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular disease (reviewed in Ref. 8). The NAD+ dependence of these enzymes provides a link between metabolism and the cellular redox state with chromatin regulation and post-translational modifications of non-histone proteins.

The sirtuins have an unusual reaction mechanism in which they consume one molecule of NAD+ for every lysine that is deacetylated. The acetyl group is transferred from the targeted protein to the ribose 2′-OH of NAD+, which is coupled to hydrolysis of the NAD+ and release of free nicotinamide (NAM) and 2′-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose as byproducts (9, 10). Because of this NAD+ consumption, it is critical for the cell to maintain pools of NAD+ that are accessible to the sirtuins in their subcellular compartments (i.e. the cytosol, nucleus, or mitochondria). This is accomplished through the combined action of a set of NAD+ biosynthesis and salvage pathways (depicted in Fig. 4A). Key to the maintenance of NAD+ for usage by Sir2 and the other nuclear yeast sirtuins (Hst1, Hst3, and Hst4) is the nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase Npt1, which is highly enriched in the nucleus (11, 12) and converts nicotinic acid (NA) to NA mononucleotide (13), an intermediate that is shared with the de novo NAD+ biosynthesis pathway. NA is the default NAD+ precursor supplied in typical yeast growth media. The NAM produced by sirtuins is converted to NA through a deamidation reaction catalyzed by the nicotinamidase Pnc1 (14–16). The conversion of NA to NAD+ is generally known as the Preiss-Handler pathway (17). In this study, we will refer to the combination of Pnc1 and Npt1 activities as the “NAD+ salvage” pathway. Modulation of this pathway has significant effects on Sir2-mediated silencing and life span (11, 12).

FIGURE 4.

NAD+ salvage pathway contributes to INAM-induced increases in NAD+. A, diagram of the known NAD+ biosynthesis pathways in S. cerevisiae. NAD+ biosynthesis occurs through five known pathways: from tryptophan through the de novo pathway (1), NAM salvage (2), and NR salvage via Nrk1 (3) or via conversion to NAM (4). NA can be imported either via the high affinity NA permease Tna1 or through hydrolysis of NA riboside (NaR) (pathway 5). NaMN, NA mononucleotide; NaAD, NA adenine dinucleotide. B, WT (JM346), bna1Δ (CGY153), pnc1Δ (JM447), and bna1Δ pnc1Δ (JM449) cells were streaked for single colonies onto NA-free (−NA) SC medium and NA-free medium supplemented with 25 mm INAM. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. C, NAD+ concentrations for WT (JM346), npt1Δ (JM258), pnc1Δ (JM447), bna1Δ (CGY153), and tna1Δ (JS932) strains grown in the indicated media. The statistical significance of the increased NAD+ concentrations is indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. For each strain, the p value comparisons are with the matching cultures lacking INAM.

NAM is a potent sirtuin inhibitor, so it is critical for the cell to limit its concentration. In bacteria, yeast, plants, and most invertebrate animals, this is accomplished by Pnc1-mediated deamidation (16, 18–20). In the absence of Pnc1, NAM accumulates and inhibits sirtuin activity, thus resulting in Sir2 silencing defects and derepression of Hst1-repressed genes in the yeast system (15). Overexpression of PNC1 suppresses the inhibitory effect of NAM on sirtuins and has even been demonstrated to extend RLS (14, 15), so Pnc1 is important not only for NAD+ salvage but also for “detoxifying” NAM to promote sirtuin activity. Vertebrates do not encode a Pnc1 homolog but instead have a nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) that converts NAM to NMN, another intermediate of NAD+ biosynthesis (21). Through this function, NAMPT also serves the role of detoxifying the NAM for sirtuins. Therefore, in both cases (Pnc1 and NAMPT), the NAM produced by sirtuins is recycled back into NAD+, albeit through different mechanisms.

With the increasingly large number of disease-related target proteins for deacetylation by the sirtuins, there is a great deal of interest in the identification and characterization of small molecule agonists and antagonists that can be used as research tools and/or pharmacological therapeutics. There are several classes of direct sirtuin inhibitors, including NAM (9, 22), splitomicin (23), and sirtinol (24). Sirtuin agonists include the red wine compound resveratrol (25) and other related polyphenol compounds called STACs (sirtuin-activating compounds), which activate the human SIRT1 enzyme by increasing the binding affinity of SIRT1 for its acetylated target protein (26), although the specificity of these compounds has been challenged (27, 28). A close analog of NAM called isonicotinamide (INAM) (see Fig. 1A) has been shown to activate yeast Sir2 in vitro through a different mechanism, by blocking the inhibition caused by NAM (29). Here, we provide evidence that, in addition to relieving the inhibitory effect of NAM, INAM also stimulates Sir2 activity in vivo by raising the intracellular NAD+ concentration via the Npt1/Pnc1 salvage pathway in yeast, which results in enhanced silencing and extension of RLS. INAM therefore represents a novel class of sirtuin agonists with both direct and indirect stimulatory effects on sirtuins.

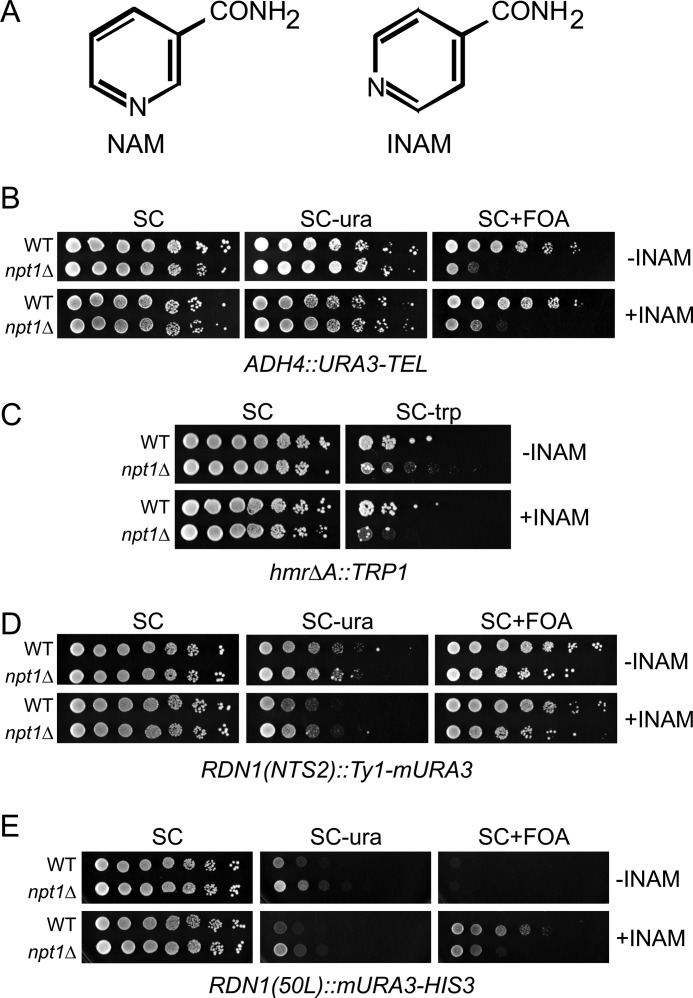

FIGURE 1.

INAM effects on telomeric, HMR, and rDNA silencing. A, chemical structures of NAM and INAM. B, telomeric silencing of the URA3 gene in WT (YCB647) and npt1Δ (JS641) strains. INAM (25 mm) was added where indicated. C, silencing of a TRP1 gene positioned at the HMR locus. 5-Fold serial dilutions of the WT (YLS50) or npt1Δ (JS643) strain were spotted. Silencing is indicated by reduced growth on SC-Trp. D, rDNA silencing measured by a Ty1-mURA3 marker integrated within the rDNA array at NTS2. WT (JS125) and npt1Δ (JS586) strains were spotted as 5-fold serial dilutions. E, rDNA silencing assay in which the mURA3-HIS3 reporter cassette was stably integrated 50 bp left of the array (50L). The WT (JM346) and npt1Δ (CGY145) strains were spotted as 5-fold dilutions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

Yeast media were described previously (6, 12). Synthetic complete (SC) and rich yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YPD) media were supplemented with INAM (Sigma) where indicated. SC medium contained 3.25 μm NA (Difco). Strains grown on SC plates lacking NA (SC-NA) had strips of agar removed to prevent cross-feeding between different strains on the same plate. Yeast strains were grown at 32 °C for rDNA silencing and at 30 °C for all other experiments. NPT1, BNA1, PNC1, TNA1, NRK1, SIR2, and HST1 open reading frames were deleted and replaced with kanMX4 using one-step gene replacement (30) and verified by PCR. Strains with multiple gene deletions were obtained through genetic crosses and tetrad dissections. The genotypes of strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| YCB647a | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 lysΔ202 ura3-52 leu2Δ::TRP1 ADH4::URA3-TEL |

| JS641a | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 lysΔ202 ura3-52 leu2Δ::TRP1 ADH4::URA3-TEL npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| YLS59b | MATα his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 ura3-1 ade2-1 can1-100 hmrΔA::TRP1 |

| JS643a | MATα his3-11,15 leu2-3 trp1-1 ura3-1 ade2-1 can1-100 hmrΔA::TRP1 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JS125c | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (NTS2)::Ty1-mURA3 |

| JS586 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (NTS2)::Ty1-mURA3 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM346 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 |

| JM258 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| BY4741d | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| BY4742d | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 |

| SY163e | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hst1Δ::kanMX4 |

| SY533e | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 sir2Δ::kanMX4 |

| CGY145f | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| CGY153f | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 met15Δ0 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 bna1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM447 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 pnc1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM449 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 bna1Δ::kanMX4 pnc1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JS932f | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 tna1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JS944g | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 met15Δ0 ura3-167 RDN (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 nrk1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM204 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 bna1Δ::kanMX4 tna1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM236 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 ura3-167 RDN1 (50L)::mURA3-HIS3 nrk1Δ::kanMX4 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

| JM518 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 nrk1Δ::kanMX4 |

| PAB046g | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 pnp1Δ::kanMX4 urh1Δ::NAT |

| PAB038g | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 nrk1Δ::HIS3 pnp1Δ::kanMX4 urh1Δ::NAT |

| PAB052g | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 nrk1Δ::HIS3 pnp1Δ::kanMX4 urh1Δ::NAT meu2Δ::LEU2 |

| JM462 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 nrk1Δ::HIS3 pnp1Δ::kanMX4 urh1Δ::NAT meu2Δ::LEU2 bna1Δ::kanMX4 |

| SY8e | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 bna1Δ::kanMX4 |

| SY16e | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 npt1Δ::kanMX4 |

Silencing Assay

Strains were grown overnight as patches on YPD plates. The cells were then scraped from the plates, resuspended in sterile water, and normalized to A600 = 1.0. 5-Fold serial dilutions were then spotted onto the appropriate SC plates as described previously (31). INAM (25 mm) was added where indicated. Photographs of SC, SC plates lacking Trp (SC-Trp), and SC plates lacking Ura (SC-Ura) were taken after 2 days of growth, and photographs of SC/5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA) plates were taken after 3 days of growth.

Intracellular NAD+ Measurements

Acid extraction of NAD+ was performed as described previously (31), with the exception that the starting yeast cultures were reduced from 500 to 50 ml, and all subsequent volumes were reduced by 10-fold. Cultures were grown to A600 ∼ 1.5 and then harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were extracted for 30 min with 500 μl of ice-cold 1 m formic acid (saturated with butanol). 125 μl of ice-cold 100% TCA was added and incubated on ice for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 400 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and the acid-soluble supernatant was saved. The pellet was re-extracted with 250 μl of 20% TCA and pelleted again. The supernatants were combined and used for NAD+ measurements. 150 μl of the acid extract was added to 850 μl of reaction buffer containing 300 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9.7), 200 mm lysine HCl, 0.2% ethanol, and 150 μg/μl alcohol dehydrogenase (Sigma). Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 20 min, and absorbance was measured at 340 nm. A base-line correction was made by subtracting the absorbance of a reaction without alcohol dehydrogenase. The cellular NAD+ concentration was calculated from the extinction coefficient as described previously (32). NAD+ measurements in H1299 cells were performed using the same protocol except that 10 ml of H1299 cells at 90% confluence was harvested. Cell density was determined using a hemocytometer. At least three biological replicates were tested for each strain or growth condition. The statistical significance of changes induced by INAM was calculated using Student's t test.

Pnc1-mediated Deamidation Reaction

Deamidation reactions were carried out as described previously by tracking the amount of ammonia byproduct produced by a nicotinamidase reaction (15, 16). Recombinant His10-tagged Pnc1 was incubated with the indicated concentrations of NAM or INAM for 90 min at 30 °C in a 100-μl reaction volume containing 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 1 mm MgCl2. Ammonia concentrations were determined using an ammonia diagnostic kit (AA0100, Sigma-Aldrich). A correction for base-line ammonia production was made by subtracting the ammonia produced in 100-μl reactions incubated without NAM or INAM substrate.

RLS Assay

Cells were inoculated into 5-ml cultures of SC medium and grown overnight at 30 °C. Cultures were diluted to A600 = 0.2, and incubation was continued at 30 °C for ∼3 h. 100 μl of the resulting cultures was diluted into 900 μl of distilled H2O and spread down one side of each plate. For each condition, 49 small budded cells were isolated by micromanipulation, staged within the plate grid for life span determination, and incubated at 30 °C for 70-min intervals. Daughters were separated from mothers, counted, and discarded to the side of the plate. The plates were wrapped in Parafilm and stored at 4 °C each night during the experiments.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Individual colonies of BY4741 were inoculated into 10 ml of SC medium and grown overnight at 30 °C. From the overnight cultures, 10 ml of SC medium or SC medium + 25 mm INAM was inoculated to a starting A600 of 0.05 in 15-ml glass culture tubes with loose fitting metal caps. These cultures were then incubated at 30 °C for 5 days while rotating in a roller drum. Total RNA was isolated from each sample using an acid/phenol protocol (33), and 1 μg of RNA from each sample was used to synthesize cDNA with oligo(dT) primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR analysis with SYBR Green was performed using an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system. ACT1 RNA levels were used to normalize expression data between samples.

RESULTS

Stimulatory Effects of INAM on Silencing Are Partially Dependent on NPT1

INAM was previously shown to enhance the catalytic activity of Sir2 in vitro by blocking NAM inhibition. Additionally, adding 25 mm INAM to yeast growth media strengthened silencing at telomeres, the HM loci, and the rDNA locus, suggesting that Sir2 activity is also enhanced in vivo (29). We were initially interested in using INAM as a tool to stimulate silencing and found that, with our standard SC growth medium, 25 mm INAM had little effect on silencing of a telomeric URA3 reporter gene (Fig. 1B, WT strain) or a TRP1 reporter integrated at the silent HMR locus (Fig. 1C, WT strain). This was a surprising result given the earlier INAM report but was consistent with previous findings that SIR2 overexpression does not significantly enhance HM or telomeric silencing (4, 34).

Silencing at the rDNA locus is typically more sensitive to changes in SIR2 dosage (35, 36), so we also tested the effect of INAM on a Ty1-mURA3 marker that was integrated into the NTS2 (non-transcribed spacer 2) region of the rDNA (6). This time, INAM did enhance silencing, as indicated by a mild reduction in growth on SC-Ura (Fig. 1D). However, silencing on SC/FOA plates could not be accurately measured in this strain because of the relatively high frequency of mitotic recombination within the rDNA array. Therefore, we also utilized a strain in which the mURA3 reporter gene was stably integrated into unique chromosome XII sequence, 50 bp left of the rDNA array (YSB348) (37). Silencing of mURA3 at this position results in poor growth on SC-Ura but is not strong enough to induce growth on FOA unless SIR2 is overexpressed or silencing is improved by other means (38). As shown in Fig. 1E, INAM again strengthened rDNA silencing, as indicated by weaker growth on SC-Ura, and the silencing was strong enough to make the strain FOA-resistant.

Because Sir2 is an NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase, its silencing function is dependent on the maintenance of a sufficiently high intracellular NAD+ concentration, which requires the Npt1 protein of the NAD+ salvage pathway (31, 39). The stimulatory effect of INAM on silencing was originally reported to be independent of the NAD+ salvage pathway, which was consistent with its in vitro mechanism of Sir2 activation (29). In our hands, the silencing defects caused by deleting NPT1 were only partially suppressed by the addition of INAM (Fig. 1, B–E), possibly also implicating NAD+ in the mechanism of Sir2 activation in vivo.

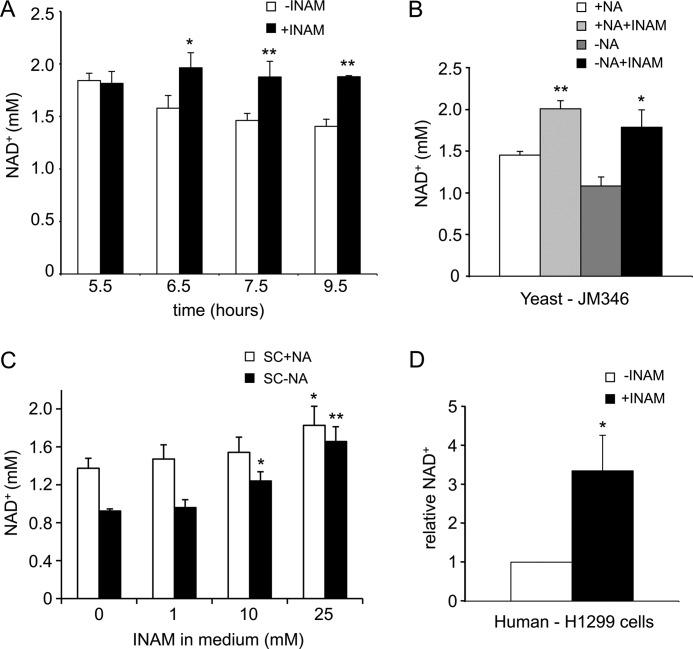

INAM Raises Intracellular NAD+ Concentration

We next tested whether the addition of 25 mm INAM to SC medium had any effect on the intracellular NAD+ concentration. As shown in Fig. 2A, the NAD+ concentration steadily declined as yeast cultures reached the end of log phase and approached the diauxic shift, which was due to depletion from the growth medium of the limiting NAD+ precursor NA (12, 32). Supplementing the SC medium with 25 mm INAM prevented the reduction in NAD+ (Fig. 2A), which was similar to the effect of adding nicotinamide riboside (NR), another NAD+ precursor, to the growth medium (32). For subsequent NAD+ measurements throughout this study, we used the 6.5-h late log time point to measure effects on NAD+ concentration. Simply excluding NA from SC medium reduces intracellular NAD+ across the entire growth time course, even in log phase (data not shown) (32). The addition of 25 mm INAM to the NA-free SC medium fully restored the NAD+ concentration to a level similar to that observed in the presence of NA (Fig. 2B). INAM concentrations <10 mm had little effect on the NAD+ level (Fig. 2C), which differed significantly from the low micromolar concentrations of NA or NR that are directly utilized for NAD+ biosynthesis (12, 32). To confirm that this increase in NAD+ concentration is not a peculiarity of the yeast system, we also tested whether INAM elevates the NAD+ concentration in a human cell line. As shown in Fig. 2D, the addition of 25 mm INAM to standard cell culture DMEM caused an ∼3-fold increase in NAD+ concentration in the human non-small cell lung cancer cell line H1299. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that INAM has the potential to activate sirtuins in vivo by preventing NAM inhibition and by increasing the concentration of their critical co-substrate, NAD+.

FIGURE 2.

INAM raises NAD+ concentration in yeast and human cells. A, intracellular NAD+ concentration of WT cells (JM346) grown with or without 25 mm INAM. Medium supplemented with INAM maintained high NAD+ levels over time. B, NAD+ concentration of WT cells (JM346) increased with the addition of INAM. Cells were grown to A600 ∼ 1.5 in SC medium either containing NA (+NA) or lacking NA (−NA). C, effect of INAM titration on NAD+ concentration in NA-containing or NA-free SC medium. Cells were grown to A600 = 1.5, which is late log phase. D, relative NAD+ concentration in H1299 cells grown with or without 25 mm INAM. The statistical significance of the increased NAD+ concentrations is indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005.

Positive Effects of INAM on RLS

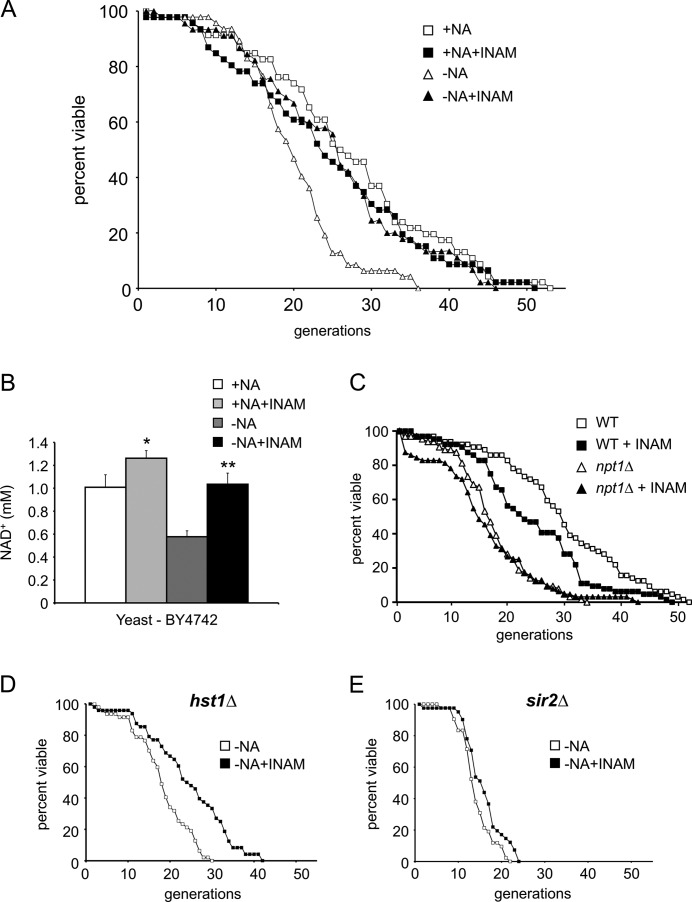

Given the positive effect of INAM on transcriptional silencing and its unexpected ability to raise the intracellular NAD+ concentration in both yeast and human cells, we hypothesized that INAM would have a positive effect on yeast RLS. Sir2 has been shown to promote yeast RLS through at least two independent pathways involving histone deacetylation. The first involves Sir2-mediated suppression of rDNA recombination (7, 40), and the second involves specific histone H4 Lys-16 deacetylation at subtelomeric regions (41). In either pathway, a decrease in NAD+ concentration is predicted to weaken Sir2 activity and shorten RLS. Indeed, reducing NAD+ by either deleting NPT1 or growing cells on NA-free SC medium shortens RLS (32). As shown in Fig. 3A, RLS of the WT BY4741 strain was decreased on NA-free SC medium (open triangles) compared with standard SC medium (+NA; open squares). Supplementing the NA-free SC medium with INAM extended RLS back to normal (Fig. 3A, closed triangles), which was very similar to the previously observed effect of NR supplementation on RLS (32). We next tested whether INAM elevates the NAD+ concentration in the BY4741 strain background, which was distinct from the JB740-type background used in Figs. 1 and 2. As expected, the absence of NA caused an ∼50% reduction in NAD+, which was restored by INAM (Fig. 3B). From these results, we surmised that INAM promoted RLS, at least partially, by raising the intracellular NAD+ concentration. Consistent with this model, INAM did not rescue the short RLS of an npt1Δ mutant, even on rich YPD medium (Fig. 3C, triangles). Surprisingly, INAM also did not further extend RLS of the WT strain when NAD+ concentrations were already sufficiently high in cells growing on NA-containing SC medium (Fig. 3A) or YPD medium (Fig. 3C). INAM is therefore not directly mimicking calorie restriction, which does extend RLS of WT cells growing on SC or YPD medium (39, 42).

FIGURE 3.

INAM extends RLS by elevating NAD+ concentration. A, the WT yeast strain (BY4741) was subjected to RLS assay in standard SC medium with (■) or without (□) INAM. When medium lacking NA (−NA; △) was supplemented with 25 mm INAM (▴), RLS was extended. B, NAD+ concentrations when WT cells (BY4742) were grown in NA-free medium with or without 25 mm INAM. The statistical significance of the increased NAD+ concentrations is indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. C, RLS assay with WT (BY4741) and npt1Δ (SY16) strains grown on YPD plates with or without 25 mm INAM. D, RLS assay performed with an hst1Δ mutant (SY163) on NA-free SC medium with or without 25 mm INAM. E, RLS assay performed with a sir2Δ mutant (SY533) on NA-free SC medium with or without 25 mm INAM.

To determine whether the positive effect of INAM on RLS under these conditions was specifically mediated by SIR2, we measured the life spans of sir2Δ and hst1Δ strains grown on SC medium lacking NA. Hst1 is a closely related sirtuin that is considered to be a true paralog of Sir2 (43). Deletion of HST1 had little effect on RLS in this medium (mean = 18.2 generations versus 20.0 for the WT), and the addition of INAM extended the mean life span to 24.5 generations (Fig. 3D), which was similar to its effect on the WT (25.3 generations). In contrast, RLS of the sir2Δ mutant was further shortened on the SC-NA (mean = 14.2 generations) compared with RLS of the WT (mean = 20.0 generations), and INAM had little effect on the sir2Δ mutant (Fig. 3E). SIR2 is therefore required for the INAM-induced extension of RLS in response to the restoration of an optimal intracellular NAD+ concentration.

INAM-induced Increase in NAD+ Is Primarily Dependent on the Salvage Pathway

We next investigated the mechanism by which INAM promotes high intracellular NAD+ concentrations in yeast cells. Because NPT1 was partially required for the enhancement of silencing induced by INAM (Fig. 1) and its deletion blocked the effect of INAM on RLS, this pointed to involvement of the NAD+ salvage (Preiss-Handler) pathway (Fig. 4A, pathway 2). This was first tested genetically. Mutants in the de novo NAD+ biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 4A, pathway 1) such as bna1Δ are NA auxotrophs (44). As shown in Fig. 4B, bna1Δ cells were unable to grow on NA-free SC medium, but supplementation with 25 mm INAM suppressed the growth defect. However, INAM did not suppress the auxotrophic growth defect of a bna1Δ pnc1Δ double mutant, suggesting that INAM may induce flux through the NAD+ salvage pathway. To test this hypothesis more directly, we measured the intracellular NAD+ concentration in npt1Δ and pnc1Δ mutants treated with INAM. Deleting either of these salvage pathway genes prevented significant increases in NAD+ induced by INAM, regardless of whether or not NA was included in the SC medium (Fig. 4C). In contrast, INAM increased the NAD+ concentration in bna1Δ and tna1Δ strains (Fig. 4C), indicating that neither the Bna1-mediated biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 4A, pathway 1) nor NA import is individually critical for the INAM response. From these results, we can conclude that INAM can raise NAD+ concentrations in the cell by somehow increasing flux through the NAD+ salvage pathway.

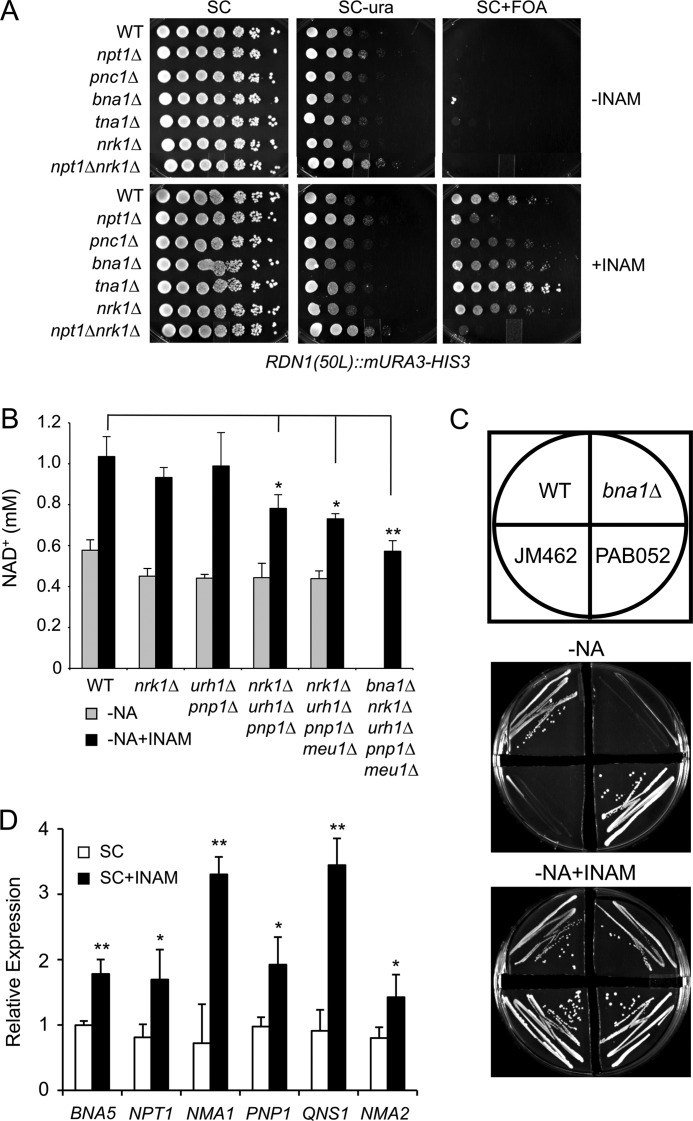

NR Salvage Pathways Contribute to INAM-mediated NAD+ Production

The data so far suggested that INAM was affecting one or more processes upstream of Pnc1 that produce NAM as an intermediate. When assaying for rDNA silencing in the presence of INAM, we noticed that an npt1Δ nrk1Δ double mutant had a more severe silencing defect than the npt1Δ mutant (Fig. 5A). This was an initial clue that the NR salvage pathways could be involved, along with the fact that INAM behaved similarly to NR in RLS assays. Yeast cells endogenously produce NR from NMN via the nucleotidases Isn1 and Sdt1 (45). Excess NR is also released into the growth medium (45, 46), where it can be imported by the NR transporter Nrt1 (47). Within the cell, NR is phosphorylated by Nrk1 to produce NMN, which is then converted to NAD+ by the nicotinamide adenylyltransferase Nma1 or Nma2 (Fig. 4A, pathway 3) (48). Alternatively, the NR is converted to NAM by the combined action of the nucleosidase Urh1 and the phosphorylases Pnp1 and Meu1 (Fig. 4A, pathway 4) (32). The resulting NAM then feeds into the Preiss-Handler pathway (Fig. 4A, pathway 2) via deamidation by Pnc1. Therefore, we next tested whether disrupting the NRK1-dependent or NRK1-independent NR salvage pathways would prevent INAM from increasing the NAD+ concentration. As shown in Fig. 5B, nrk1Δ or urh1Δ pnp1Δ mutations did not block the INAM-induced NAD+ increase, but knocking out both pathways with either an nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ triple mutant or an nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ quadruple mutant moderately attenuated the INAM effect compared with the WT control strain.

FIGURE 5.

Contributions of NR salvage pathways to INAM-induced phenotypes. A, rDNA silencing was assayed by the growth of 5-fold serial dilutions of WT (JM346), npt1Δ (JM258), pnc1Δ (JM447), bna1Δ (CGY153), tna1Δ (JS932), nrk1Δ (JS944), and npt1Δ nrk1Δ (JM236) strains in the presence or absence of INAM. The mURA3-HIS3 reporter gene was integrated 50 bp left of the rDNA array (RDN1(50L)::mURA3-HIS3). B, NAD+ concentrations measured from WT (BY4742), nrk1Δ (JM518), urh1Δ pnp1Δ (PAB046), nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ (PAB038), nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ (PAB052), and bna1Δ nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ (JM462) strains grown in NA-free SC medium with or without 25 mm INAM. The statistical significance of the decreased NAD+ concentrations compared with the WT is indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. C, WT (BY4742), bna1Δ (SY8), nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ (PAB052), and bna1Δ nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ (JM462) strains were plated for single colonies on NA-free SC medium with or without 25 mm INAM. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. D, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of steady-state RNA levels of several NAD+ biosynthesis and salvage pathway genes. Cells were grown for 5 days in SC or SC/INAM (25 mm) medium. Relative expression is the ratio of the test gene RNA to ACT1 (actin) RNA. The statistical significance of the INAM-induced increases is indicated; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005.

The above result implicated NR salvage as a potential source of NAM, but there are likely additional pathways involved. Indeed, the response to INAM was even more attenuated when the NR salvage pathway mutations were combined with the bna1Δ mutation (Fig. 5B). As expected, this quintuple mutant was unable to grow on SC medium lacking NA (Fig. 5C, JM462 strain), which also prevented measuring NAD+ under this condition (Fig. 5B). Even though 25 mm INAM fully restored growth to the quintuple mutant on NA-free SC medium (Fig. 5C, JM462 strain), its NAD+ concentration was even lower than in the quadruple mutant (Fig. 5B). This result implies that, in the absence of the NR salvage pathways, the de novo NAD+ biosynthesis pathway also contributes to the INAM effect and suggests that multiple pathways function in the maintenance of NAD+ homeostasis during INAM treatment. In support of such a model, we found that, compared with untreated cells, supplementation with 25 mm INAM increased the relative expression levels of several diverse NAD+ biosynthesis and salvage pathway genes during stationary phase (Fig. 5D), when NAD+ levels are usually depleted.

Although 25 mm INAM supplementation restored growth to the bna1Δ nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ quintuple mutant in the absence of NA (Fig. 5C), it did not restore growth to a bna1Δ pnc1Δ mutant (Fig. 4B), indicating an absolute requirement for Pnc1 deamidation activity. We therefore tested the possibility that INAM is metabolized in a manner similar to NAM, although probably to a lesser degree. The first step of NAD+ salvage is the deamidation of NAM to NA by Pnc1, which produces ammonia as a byproduct, that can be used to follow the reaction (Fig. 6A). If INAM were directly metabolized via the salvage pathway, Pnc1 would be expected to deamidate INAM in vitro. Nicotinamidase purified from rat liver was previously shown to deamidate INAM, but with a significantly higher Km value than for NAM (49). This suggested that purified yeast Pnc1 might also display activity with high concentrations of INAM. Indeed, weak nicotinamidase activity was detected with recombinant His-tagged Pnc1 and 25 mm INAM, which increased with higher INAM concentrations (Fig. 6B). However, the activity was at least 1000-fold weaker than with NAM as the substrate (tested at 1 mm). One possible explanation for this activity is that the INAM was simply contaminated with low levels of NAM. To address this possibility, the INAM was first pretreated with recombinant Pnc1 to convert any contaminating NAM to NA. We then tested whether this INAM preparation could rescue the growth defect of a bna1Δ tna1Δ mutant in NA-free SC medium. The absence of Tna1 prevents NA in the preparation from being imported. Lower concentrations of INAM (0.25–1 mm) were tested to make the growth assay more sensitive. As shown in Fig. 6C, Pnc1-treated INAM facilitated slow growth of the mutant, which was very similar to the growth induced by untreated INAM. This result strongly suggests that the growth-inducing property of INAM was not the result of contaminating NAM.

FIGURE 6.

INAM utilization in vitro and in vivo. A, schematic diagram of the Pnc1-catalyzed NAM deamidation reaction. NA and NH3 are the products. B, deamidation assay in which recombinant Pnc1 was incubated with NAM (1 mm) as a positive control or INAM (25, 100, 400, and 1000 mm). The n/a reaction is a negative control without any added NAM or INAM. Activity was measured by the concentration of ammonia produced after 90 min. The statistical significance of the activity compared with the control is indicated: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. C, growth assay for a bna1Δ tna1Δ mutant (JM204) that grows very poorly in the absence of NA (NA-free SC medium). INAM that was either untreated or pretreated with Pnc1 was added to NA-free SC medium at the indicated concentrations. The absorbance (ABS) of the cultures at 600 nm was measured at the various time points. Pnc1 treatment did not block the growth stimulatory activity of INAM. Error bars are S.D.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that INAM stimulates Sir2-dependent rDNA silencing and promotes RLS, in part, by unexpectedly elevating the intracellular NAD+ concentration in yeast cells. This is in addition to the ability of INAM to directly stimulate NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase activity through the relief of NAM inhibition (29). Several studies have used INAM as a means of activating Sirt1 in cell culture systems. For example, the addition of INAM to mesenchymal stem cells during differentiation to osteoblasts blocks the co-production of adipocytes, presumably via activation of Sirt1 (50). Additionally, INAM has been shown to induce apoptosis of osteosarcoma and HL-60 cell lines (51, 52), which is consistent with the ability of SIRT1 to potentiate apoptosis of HEK-293 cells in response to TNFα through the deacetylation of NF-κB (53). In yeast cells, a recent study showed INAM to reduce protein aggregation in a model of Huntington disease through a Sir2-dependent mechanism (54). In each case, it is possible that elevated NAD+ could contribute to the resulting phenotypes.

When INAM was first shown to be a Sir2 agonist, its positive effect on silencing was found to be independent of the NAD+ salvage pathway (29). We were therefore surprised to observe only partial suppression of the silencing defects by INAM (Fig. 1), although this led to a search for changes in NAD+ concentration. The reason for the silencing differences between these studies is currently unclear but could potentially be related to differences in the synthetic growth medium composition (SC versus Hartwell's complete) and/or growth conditions. For example, by slightly raising the incubation temperature from 30 to 32 °C, we found the FOA-resistant silencing phenotype, especially for the rDNA, to be more responsive to the defect in NAD+ salvage. Simply raising the NAD+ concentration by supplementing standard SC medium with NR was not sufficient to enhance silencing in an NPT1+ strain (data not shown) (32), strongly suggesting that the combination of increased NAD+ and relief of NAM inhibition provided by INAM is critical for this phenotype. For RLS stimulation by INAM, the maintenance of NAD+ homeostasis may be more critical, especially because INAM extended RLS only when NAD+ levels were already pre-lowered by either excluding NA from the SC medium or deleting NPT1.

The observed increase in NAD+ concentration induced by INAM is largely dependent on Npt1 and Pnc1 (Fig. 4C). Because Pnc1 is a nicotinamidase, this suggests that INAM somehow increases the flux of NAM through the salvage pathway. We first hypothesized that INAM up-regulates the expression or activity of pathways that feed into the salvage pathway via NAM production. These could be either enzymes in the currently known pathways (Fig. 4A) or perhaps a cryptic pathway that becomes active only in the presence of INAM. There is precedent for an NAD+ precursor affecting expression of a protein involved in NAD+ biosynthesis. Supplementing yeast cultures with high NA concentrations results in increased steady-state expression of Isn1, one of the nucleotidases that generate NR and NA riboside from NMN and NA mononucleotide, respectively (45). Early on, we suspected that NR might be an upstream source of NAM because the ability of INAM to maintain high NAD+ concentrations during the log-to-diauxic growth transition (Fig. 2A) was similar to the previously observed effect of exogenous NR on NAD+ concentration (32). NR does appear to be one of the sources of NAM that feeds into the salvage pathway because the relative increase in NAD+ concentration induced by INAM supplementation is attenuated in strains defective for NR utilization (Fig. 5B). However, there is still a significant increase in NAD+ even in an nrk1Δ urh1Δ pnp1Δ meu1Δ quadruple mutant, indicating that NR is not the only source of NAM. We observed an additive effect of deleting the de novo NAD+ biosynthesis gene BNA1 on INAM-induced NAD+ concentration (Fig. 5B, quintuple mutant), suggesting that, in the absence of one or more NAD+ biosynthesis/salvage pathways, INAM forces the cell to utilize remaining pathways to survive, consistent with the importance of maintaining cellular NAD+ homeostasis.

We cannot rule out the possibility that INAM is directly metabolized by yeast cells to produce NAD+ when present at high millimolar concentrations. Pnc1-mediated nicotinamidase activity is not detectable in vitro with 500 μm INAM as a substrate (55), but some activity was detectable in vitro above 25 mm (Fig. 6C). These concentrations are equivalent to the high concentration necessary for INAM (Ki = 68 mm) to block the NAM exchange reaction of Sir2 (29). Pnc1-mediated deamidation of INAM would produce isonicotinic acid, although it seems unlikely that this would go on to form iso-NAD+. It is more likely that the initial import and/or metabolism of INAM would induce increased expression of other pathway members, which would then lead to the maintenance of high NAD+ concentration during the transition to stationary phase. This was exactly what we observed for BNA5, NPT1, NMA1, NMA2, QNS1, and PNP1, each of which showed higher expression during stationary phase when cells were treated with INAM (Fig. 5D).

INAM has the unique property among current sirtuin agonists of relieving NAM inhibition. Our results add another function to its repertoire, which is elevating the intracellular NAD+ concentration. Supplementation of cells with NA or NR leads to increased NAD+ concentration because they are precursors utilized by the salvage pathways, but they do not activate sirtuin activity in vitro. Another NAD+ precursor, NAM, shares a functional property of INAM in its ability to raise the NAD+ concentration in yeast (38), although it acts as a strong sirtuin inhibitor (22). Only when PNC1 is overexpressed to clear the excess NAM (15) does the increase in NAD+ concentration induced by high NAM concentrations have any positive effect on silencing (38). Resveratrol and related STAC compounds can activate sirtuins in vitro when supplied with certain deacetylation substrates (25–28), but their in vivo mechanism of action remains unclear, especially given the additional roles of resveratrol as an antioxidant and AMP-activated protein kinase activator (56, 57).

Mounting evidence suggests that modulation of NAD+ concentration is an effective means of regulating sirtuin-controlled processes in mammals. For example, the addition of NAD+ precursor molecules such as NAM, NA, NR, and NA riboside to mammalian cells has been shown to raise NAD+ and to ameliorate certain age-associated conditions (58, 59). In addition, overexpression of NAMPT in NIH3T3 cells resolves the inhibitory effect of NAM, raises NAD+ levels, and increases SIRT1 activity (21). An extracellular form of NAMPT is found in the circulation and is thought to generate extracellular NMN that promotes insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells (60). NMN administration also leads to an elevation of NAD (61), but it has to be degraded to the nucleoside version (NR) before being imported into the cell (62). NAD+ biosynthesis via extracellular NAMPT also displays circadian oscillations that are involved in a feedback regulation of the clock system (63). The ability of INAM to prevent NAM inhibition of sirtuins and to enhance salvage of NAM into NAD+, to a close approximation, makes it a chemical mimic of NAMPT overexpression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marty Mayo, Patrick Grant, Mitch Smith, and members of the Smith laboratory for helpful suggestions and comments during the development of this project. We also thank Marty Mayo for supplying the H1299 cell line and Charles Brenner for sending yeast strains and providing NR.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM075240 and AG022685 (to J. S. S.) and Training Grant GM008136 (to J. M. M.).

- RLS

- replicative life span

- NAM

- nicotinamide

- NA

- nicotinic acid

- NAMPT

- nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

- INAM

- isonicotinamide

- SC

- synthetic complete

- YPD

- yeast extract/peptone/dextrose

- FOA

- 5-fluoroorotic acid

- NR

- nicotinamide riboside.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brachmann C. B., Sherman J. M., Devine S. E., Cameron E. E., Pillus L., Boeke J. D. (1995) The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 9, 2888–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frye R. A. (2000) Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 793–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rine J., Herskowitz I. (1987) Four genes responsible for a position effect on expression from HML and HMR in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 116, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aparicio O. M., Billington B. L., Gottschling D. E. (1991) Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66, 1279–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryk M., Banerjee M., Murphy M., Knudsen K. E., Garfinkel D. J., Curcio M. J. (1997) Transcriptional silencing of Ty1 elements in the RDN1 locus of yeast. Genes Dev. 11, 255–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith J. S., Boeke J. D. (1997) An unusual form of transcriptional silencing in yeast ribosomal DNA. Genes Dev. 11, 241–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaeberlein M., McVey M., Guarente L. (1999) The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 13, 2570–2580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haigis M. C., Sinclair D. A. (2010) Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 253–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landry J., Slama J. T., Sternglanz R. (2000) Role of NAD+ in the deacetylase activity of the SIR2-like proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanny J. C., Moazed D. (2001) Coupling of histone deacetylation to NAD breakdown by the yeast silencing protein Sir2: Evidence for acetyl transfer from substrate to an NAD breakdown product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 415–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anderson R. M., Bitterman K. J., Wood J. G., Medvedik O., Cohen H., Lin S. S., Manchester J. K., Gordon J. I., Sinclair D. A. (2002) Manipulation of a nuclear NAD+ salvage pathway delays aging without altering steady-state NAD+ levels. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18881–18890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandmeier J. J., Celic I., Boeke J. D., Smith J. S. (2002) Telomeric and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are dependent on a nuclear NAD+ salvage pathway. Genetics 160, 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rajavel M., Lalo D., Gross J. W., Grubmeyer C. (1998) Conversion of a co-substrate to an inhibitor: phosphorylation mutants of nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochemistry 37, 4181–4188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson R. M., Bitterman K. J., Wood J. G., Medvedik O., Sinclair D. A. (2003) Nicotinamide and PNC1 govern life span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 423, 181–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallo C. M., Smith D. L., Jr., Smith J. S. (2004) Nicotinamide clearance by Pnc1 directly regulates Sir2-mediated silencing and longevity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1301–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghislain M., Talla E., François J. M. (2002) Identification and functional analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae nicotinamidase gene, PNC1. Yeast 19, 215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Preiss J., Handler P. (1958) Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. I. Identification of intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 233, 488–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Balan V., Miller G. S., Kaplun L., Balan K., Chong Z. Z., Li F., Kaplun A., VanBerkum M. F., Arking R., Freeman D. C., Maiese K., Tzivion G. (2008) Life span extension and neuronal cell protection by Drosophila nicotinamidase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27810–27819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vrablik T. L., Huang L., Lange S. E., Hanna-Rose W. (2009) Nicotinamidase modulation of NAD+ biosynthesis and nicotinamide levels separately affect reproductive development and cell survival in C. elegans. Development 136, 3637–3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang G., Pichersky E. (2007) Nicotinamidase participates in the salvage pathway of NAD biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 49, 1020–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Revollo J. R., Grimm A. A., Imai S. (2004) The NAD biosynthesis pathway mediated by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates Sir2 activity in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50754–50763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bitterman K. J., Anderson R. M., Cohen H. Y., Latorre-Esteves M., Sinclair D. A. (2002) Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast Sir2 and human SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45099–45107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bedalov A., Gatbonton T., Irvine W. P., Gottschling D. E., Simon J. A. (2001) Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of Sir2p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 15113–15118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grozinger C. M., Chao E. D., Blackwell H. E., Moazed D., Schreiber S. L. (2001) Identification of a class of small molecule inhibitors of the sirtuin family of NAD-dependent deacetylases by phenotypic screening. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38837–38843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howitz K. T., Bitterman K. J., Cohen H. Y., Lamming D. W., Lavu S., Wood J. G., Zipkin R. E., Chung P., Kisielewski A., Zhang L. L., Scherer B., Sinclair D. A. (2003) Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae life span. Nature 425, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Milne J. C., Lambert P. D., Schenk S., Carney D. P., Smith J. J., Gagne D. J., Jin L., Boss O., Perni R. B., Vu C. B., Bemis J. E., Xie R., Disch J. S., Ng P. Y., Nunes J. J., Lynch A. V., Yang H., Galonek H., Israelian K., Choy W., Iffland A., Lavu S., Medvedik O., Sinclair D. A., Olefsky J. M., Jirousek M. R., Elliott P. J., Westphal C. H. (2007) Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature 450, 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borra M. T., Smith B. C., Denu J. M. (2005) Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17187–17195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaeberlein M., McDonagh T., Heltweg B., Hixon J., Westman E. A., Caldwell S. D., Napper A., Curtis R., DiStefano P. S., Fields S., Bedalov A., Kennedy B. K. (2005) Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17038–17045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sauve A. A., Moir R. D., Schramm V. L., Willis I. M. (2005) Chemical activation of Sir2-dependent silencing by relief of nicotinamide inhibition. Mol. Cell 17, 595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lorenz M. C., Muir R. S., Lim E., McElver J., Weber S. C., Heitman J. (1995) Gene disruption with PCR products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 158, 113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith J. S., Brachmann C. B., Celic I., Kenna M. A., Muhammad S., Starai V. J., Avalos J. L., Escalante-Semerena J. C., Grubmeyer C., Wolberger C., Boeke J. D. (2000) A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6658–6663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Belenky P., Racette F. G., Bogan K. L., McClure J. M., Smith J. S., Brenner C. (2007) Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends life span via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+. Cell 129, 473–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. (2000) Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2, Chapter 13 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith D. L., Jr., Li C., Matecic M., Maqani N., Bryk M., Smith J. S. (2009) Calorie restriction effects on silencing and recombination at the yeast rDNA. Aging Cell 8, 633–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fritze C. E., Verschueren K., Strich R., Easton Esposito R. (1997) Direct evidence for SIR2 modulation of chromatin structure in yeast rDNA. EMBO J. 16, 6495–6509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith J. S., Brachmann C. B., Pillus L., Boeke J. D. (1998) Distribution of a limited Sir2 protein pool regulates the strength of yeast rDNA silencing and is modulated by Sir4p. Genetics 149, 1205–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buck S. W., Sandmeier J. J., Smith J. S. (2002) RNA polymerase I propagates unidirectional spreading of rDNA silent chromatin. Cell 111, 1003–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McClure J. M., Gallo C. M., Smith D. L., Jr., Matecic M., Hontz R. D., Buck S. W., Racette F. G., Smith J. S. (2008) Pnc1p-mediated nicotinamide clearance modifies the epigenetic properties of rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 180, 797–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin S. J., Defossez P. A., Guarente L. (2000) Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289, 2126–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sinclair D. A., Guarente L. (1997) Extrachromosomal rDNA circles–a cause of aging in yeast. Cell 91, 1033–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dang W., Steffen K. K., Perry R., Dorsey J. A., Johnson F. B., Shilatifard A., Kaeberlein M., Kennedy B. K., Berger S. L. (2009) Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular life span. Nature 459, 802–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiang J. C., Jaruga E., Repnevskaya M. V., Jazwinski S. M. (2000) An intervention resembling calorie restriction prolongs life span and retards aging in yeast. FASEB J. 14, 2135–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hickman M. A., Rusche L. N. (2007) Substitution as a mechanism for genetic robustness: the duplicated deacetylases Hst1p and Sir2p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 3, e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kucharczyk R., Zagulski M., Rytka J., Herbert C. J. (1998) The yeast gene YJR025c encodes a 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid dioxygenase and is involved in nicotinic acid biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 424, 127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bogan K. L., Evans C., Belenky P., Song P., Burant C. F., Kennedy R., Brenner C. (2009) Identification of Isn1 and Sdt1 as glucose- and vitamin-regulated nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinic acid mononucleotide 5′-nucleotidases responsible for production of nicotinamide riboside and nicotinic acid riboside. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34861–34869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lu S. P., Kato M., Lin S. J. (2009) Assimilation of endogenous nicotinamide riboside is essential for calorie restriction-mediated life span extension in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17110–17119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Belenky P. A., Moga T. G., Brenner C. (2008) Saccharomyces cerevisiae YOR071C encodes the high affinity nicotinamide riboside transporter Nrt1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8075–8079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bieganowski P., Brenner C. (2004) Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans. Cell 117, 495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Su S., Albizati L., Chaykin S. (1969) Nicotinamide deamidase from rabbit liver. II. Purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 2956–2965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bäckesjö C. M., Li Y., Lindgren U., Haldosén L. A. (2006) Activation of Sirt1 decreases adipocyte formation during osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li Y., Bäckesjö C. M., Haldosén L. A., Lindgren U. (2009) Resveratrol inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 609, 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ogata S., Takeuchi M., Fujita H., Shibata K., Okumura K., Taguchi H. (2000) Apoptosis induced by nicotinamide-related compounds and quinolinic acid in HL-60 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yeung F., Hoberg J. E., Ramsey C. S., Keller M. D., Jones D. R., Frye R. A., Mayo M. W. (2004) Modulation of NF-κB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 23, 2369–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sorolla M. A., Nierga C., Rodríguez-Colman M. J., Reverter-Branchat G., Arenas A., Tamarit J., Ros J., Cabiscol E. (2011) Sir2 is induced by oxidative stress in a yeast model of Huntington disease, and its activation reduces protein aggregation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 510, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. French J. B., Cen Y., Vrablik T. L., Xu P., Allen E., Hanna-Rose W., Sauve A. A. (2010) Characterization of nicotinamidases: steady-state kinetic parameters, class-wide inhibition by nicotinaldehydes, and catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 49, 10421–10439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dasgupta B., Milbrandt J. (2007) Resveratrol stimulates AMP kinase activity in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7217–7222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Obrenovich M. E., Nair N. G., Beyaz A., Aliev G., Reddy V. P. (2010) The role of polyphenolic antioxidants in health, disease, and aging. Rejuvenation Res. 13, 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hara N., Yamada K., Terashima M., Osago H., Shimoyama M., Tsuchiya M. (2003) Molecular identification of human glutamine- and ammonia-dependent NAD synthetases. Carbon-nitrogen hydrolase domain confers glutamine dependence. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10914–10921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang H., Baur J. A., Chen A., Miller C., Adams J. K., Kisielewski A., Howitz K. T., Zipkin R. E., Sinclair D. A. (2007) Design and synthesis of compounds that extend yeast replicative life span. Aging Cell 6, 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Revollo J. R., Körner A., Mills K. F., Satoh A., Wang T., Garten A., Dasgupta B., Sasaki Y., Wolberger C., Townsend R. R., Milbrandt J., Kiess W., Imai S. (2007) Nampt/PBEF/visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 6, 363–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshino J., Mills K. F., Yoon M. J., Imai S. (2011) Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD+ intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 14, 528–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nikiforov A., Dölle C., Niere M., Ziegler M. (2011) Pathways and subcellular compartmentation of NAD biosynthesis in human cells: from entry of extracellular precursors to mitochondrial NAD generation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21767–21778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ramsey K. M., Mills K. F., Satoh A., Imai S. (2008) Age-associated loss of Sirt1-mediated enhancement of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in beta cell-specific Sirt1-overexpressing (BESTO) mice. Aging Cell 7, 78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sussel L., Shore D. (1991) Separation of transcriptional activation and silencing functions of the RAP1-encoded repressor/activator protein 1: isolation of viable mutants affecting both silencing and telomere length. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 7749–7753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., Hieter P., Boeke J. D. (1998) Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Winzeler E. A., Shoemaker D. D., Astromoff A., Liang H., Anderson K., Andre B., Bangham R., Benito R., Boeke J. D., Bussey H., Chu A. M., Connelly C., Davis K., Dietrich F., Dow S. W., El Bakkoury M., Foury F., Friend S. H., Gentalen E., Giaever G., Hegemann J. H., Jones T., Laub M., Liao H., Liebundguth N., Lockhart D. J., Lucau-Danila A., Lussier M., M'Rabet N., Menard P., Mittmann M., Pai C., Rebischung C., Revuelta J. L., Riles L., Roberts C. J., Ross-MacDonald P., Scherens B., Snyder M., Sookhai-Mahadeo S., Storms R. K., Véronneau S., Voet M., Volckaert G., Ward T. R., Wysocki R., Yen G. S., Yu K., Zimmermann K., Philippsen P., Johnston M. (1999) Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285, 901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]