Background: Heteromeric αβ glycine receptor β+/α− interfaces have never been characterized unambiguously.

Results: This interface, compared with the α+/α− interface, is highly sensitive to agonist and experiences distinct conformational changes upon agonist binding.

Conclusion: The β+/α− interface exhibits distinct properties.

Significance: Our investigation directs the β+/α− interface-specific drug design and provides a general methodology for unambiguously characterizing heteromeric proteins interfaces.

Keywords: Cys-loop Receptors, GABA Receptors, Glycine Receptors, Ligand Binding Protein, Neurotransmitter Receptors, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, Protein Chimeras, Protein Domains, Heteromeric Protein, Protein Interface

Abstract

The glycine receptor (GlyR) exists either in homomeric α or heteromeric αβ forms. Its agonists bind at extracellular subunit interfaces. Unlike subunit interfaces from the homomeric α GlyR, subunit interfaces from the heteromeric αβ GlyR have not been characterized unambiguously because of the existence of multiple types of interface within single receptors. Here, we report that, by reconstituting β+/α− interfaces in a homomeric GlyR (αChb+a− GlyR), we were able to functionally characterize the αβ GlyR β+/α− interfaces. We found that the β+/α− interface had a higher agonist sensitivity than that of the α+/α− interface. This high sensitivity was contributed primarily by loop A. We also found that the β+/α− interface differentially modulates the agonist properties of glycine and taurine. Using voltage clamp fluorometry, we found that the conformational changes induced by glycine binding to the β+/α− interface were different from those induced by glycine binding to the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR. Moreover, the distinct conformational changes found at the β+/α− interface in the αChb+a− GlyR were also found in the heteromeric αβ GlyR, which suggests that the αChb+a− GlyR reconstitutes structural components and recapitulates functional properties, of the β+/α− interface in the heteromeric αβ GlyR. Our investigation not only provides structural and functional information about the GlyR β+/α− interface, which could direct GlyR β+/α− interface-specific drug design, but also provides a general methodology for unambiguously characterizing properties of specific protein interfaces from heteromeric proteins.

Introduction

The Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels are postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors, and include the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR),2 the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor, the type-A γ-aminobutyric acid receptor (GABAAR), and the glycine receptor (GlyR) (1–5). Members of this receptor family exist predominantly as heteromeric pentamers and are constructed from a group of homologous subunits that varies in size from five (α1–4 and β) for the GlyR to 19 for the GABAAR. Each pentameric subunit combination exhibits a unique electrophysiological and pharmacological profile. This creates a wide functional diversity within a given receptor type, which is essential for optimal nervous system function and also provides an opportunity for pharmacologists to design treatments for specific pathophysiological conditions. Ligand-binding sites are found at subunit interfaces, and the structure, and hence the functional properties, of these sites are determined by the subunits that contribute to the formation of these interfaces. It is difficult to characterize the functional properties of an individual ligand-binding site due to the variety of sites that co-exist within a given heteromeric pentamer.

Each Cys-loop receptor subunit is composed of an N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD), four transmembrane domains, termed M1–M4, and a large intracellular domain between M3 and M4. The channel pore is lined by M2 domains contributed by each subunit. Agonist binding to the receptor ECD initiates a local conformational change that propagates away from the binding site, ultimately leading to the opening of a gate in the channel pore (9–14). Each ECD is composed primarily of two β sheets, where β strands are connected by flexible loops. As noted above, agonist binding sites are located at the ECD subunit interfaces. Loops A, B, and C from the principal (+) subunit interface and loops D, E and F (and loop G in some cases) from the complementary (−) subunit interface form a pocket that hosts the agonist binding site (6–8), whereas loop 2, the conserved Cys-loop, and the pre-M1 linker form a transition zone, which connects the ECD to the transmembrane domain (7, 9–14). Despite sharing common structural and functional characteristics, ECD subunit interfaces formed by different combinations of subunits do not contribute equally to agonist binding. For example, in the muscle α2βγδ nAChR, only the α+/γ− and α+/δ− subunit interfaces have the ability to bind the agonist, acetylcholine (15). Likewise, the α2β2γ GABAAR binds its agonist GABA only at the two β+/α− interfaces (16–18). In contrast to the heteromeric nAChR and GABAAR, the heteromeric α2β3 GlyR is thought to bind the agonist glycine at all available subunit interfaces (19). In addition to forming the binding site for agonists, the ECD subunit interface also forms the binding site for modulators of clinical importance. For example, benzodiazepines bind to the GABAAR at the α+/γ− (2, 3, 17), or occasionally at the α+/β− ECD subunit interfaces (20, 21), but not the GABA-binding β+/α− ECD subunit interface. To precisely understand the functional properties of Cys-loop receptors, it is essential to unambiguously characterize individual subunit interfaces without interference from other subunit interfaces. However, this generally is not possible using traditional site-directed mutagenesis strategies as a given mutation may interfere with more than one type of interface. For example, to investigate the properties of the (+) side of the α+/γ− interface in the α2βγδ nAChR, mutations would be introduced into the α+ side, and their effect would be examined by functional assays such as electrophysiological recording. However, any effect detected in this way might arise from the mutation occurring at the α+/δ− rather than α+/γ− interfaces. The traditional methodology cannot distinguish these two possibilities.

This was the situation before structural information became available. The past 10 years has seen structures of various Cys-loop receptors revealed (6, 8, 9, 11). Here, we used this structural information to reconstitute the β+/α− interface of the heteromeric αβ GlyR in a homomeric GlyR, by building a complex chimera. The chimeric GlyR allowed us to unambiguously characterize the properties of the β+/α− interface by comparing it with the α+/α− interface. We found that the β+/α− interface has a higher agonist sensitivity than that of the α+/α− interface. In addition, the conformational changes that occur at the β+/α− interface upon agonist binding are different from those occurring at the α+/α− interface. Our investigation not only provides functional and structural information of the GlyR β+/α− interface, which would direct GlyR β+/α− interface-specific drug design, but also provides a general methodology for unambiguously characterizing properties of specific protein interfaces from heteromeric proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis and Chimera Construction of GlyR cDNAs

The human GlyR α1 and β cDNAs were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1zeo+ (Invitrogen) or pGEMHE (22) plasmid vectors for expression in HEK293 cells or Xenopus oocytes, respectively. Site-directed mutagenesis and chimera construction were performed using the QuikChange (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) mutagenesis and multiple-template-based sequential PCR protocols, respectively.

The multiple-template-based sequential PCR protocol for chimera construction was developed in our laboratory and recently has been described in detail elsewhere (23). This procedure does not require the existence of restriction sites or the purification of intermediate PCR products and needs only two or three simple PCRs followed by general subcloning steps. Most importantly, the chimera join sites are seamless, i.e. no linker sequence is required, and the success rate for construction is nearly 100%. The joining sites used in our experiment were chosen based on two criteria. First, the site, based on the crystal structure of the acetylcholine binding protein (5), should be located near the boundary between the two flanking loops to minimize disturbance on the loop structures. Second, the pair of residues between which a joining site is formed should be conserved between the GlyR α and β subunits, if possible. The joining sites used in our experiment are between the following pairs of residues: α Ile93-Trp94 and β Leu116-Trp117 for the N terminus of loop A, α Phe108-His109 and β Phe131-His132 for the C terminus of loop A and the N terminus of loop E, α Leu134-Thr135 and β Ile157-Thr158 for the C terminus of loop E and the N terminus of the Cys-loop, α Gln155-Leu156 and β Gln178-Leu179 for the C terminus of the Cys-loop and the N terminus of loop B, α Glu172-Gln173 and β Ser195-Gly196 for the C terminus of loop B and the N terminus of loop F, α Glu192-Lys193 and β Asp215-Ile216 for C terminus of loop F and the N terminus of the loop C, α Thr208-Cys209 and β Thr232-Cys233 for the C terminus of loop C and the N terminus of the pre-M1 linker, and α Gly221-Tyr222 and β Gly245-Phe246 for the C terminus of the pre-M1 linker and the N terminus of the transmembrane domain (supplemental Fig. 1). The loop 2 transposition was achieved by incorporating either the αA52Q or βQ73A mutations, as the loop 2 sequences between the α1 and β subunits are otherwise conserved. To facilitate comparison, residue numbering in chimeric constructs is based on the respective homologous residue in the α1 subunit.

For the voltage clamp fluorometry (VCF) experiments, the cysteines equivalent to the α1 Cys41 and β Cys115 were mutated to alanines to minimize possible background labeling. Neither mutation affects channel function (24, 25).

HEK293 Cell Culture, Expression, and Electrophysiological Recording

The agonist EC50 values were determined on GlyRs expressed in HEK293 cells. Details of the HEK293 cell culture, GlyR expression, and electrophysiological recording of the HEK293 cells are described elsewhere (26). Briefly, HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected using a calcium phosphate precipitation protocol. In addition, the pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) was co-transfected to facilitate the identification of transfected cells. Glycine-induced currents were measured using the whole cell patch clamp configuration. Cells were treated with external Ringer's solution and internal CsCl solution (27). Cells were voltage clamped at −40 mV.

Oocyte Preparation, Expression, and VCF Recording

VCF experiments were performed on GlyRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Details of oocyte preparation, GlyR expression, and VCF recording are described elsewhere (28, 29). Briefly, the mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to generate capped mRNA. The mRNA was injected into oocytes of the female Xenopus laevis frog at a dose of 10 ng (10 ng of WT or chimeric α1 when expressing homomers, and 1 ng of α1 and 9 ng of β when expressing heteromers) per oocyte. After injection, the oocytes were incubated in ND96 solution (30) for 3–4 days at 18 °C before recording.

Sulfhydryl-reactive reagents, sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Ontario, Canada), 2-((5(6)-tetramethylrhodamine) carboxylamino)ethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTS-TAMRA, Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Ontario, Canada) and tetramethylrhodamine-6-maleimide (TMRM, Invitrogen), were used to label the introduced cysteine residues (sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate, Q219C; MTS-TAMRA, A52C, Q67C, K203C; TMRM, R217C or E217C). On the day of recording, the oocytes were labeled with 10 μm sulforhodamine methanethiosulfonate for 25 s, MTS-TAMRA (on ice) for 25 s, TMRM (on ice) for 30 min, either in the absence or presence of glycine. The oocytes were then transferred to the recording chamber and perfused with ND96 solution. The current was recorded by the two-electrode voltage clamp configuration, and the recording electrode was filled with 3 m KCl. Cells were voltage clamped at −40 mV. The fluorescence was recorded using the PhotoMax 200 photodiode detection system (Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN).

Data Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. of three or more independent experiments. The empirical Hill equation, fitted by a non-linear least squares algorithm (SigmaPlot, version 11.0, Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA), was used to calculate the EC50 and Hill coefficient (nH) values for glycine-induced current and fluorescence changes. The agonist binding/gating energy of each chimeric construct relative to that of the α1WT GlyR (ΔΔG) was determined by the formula ΔΔG(kJ/mol) = RTln(EC50chi) − RTln (EC50WT). Specifically, the variance of ΔΔG was calculated by using standard methods for error propagation (supplemental data). Statistical significance was determined using the Student's t test (SigmaPlot, version 11.0).

RESULTS

Relative Contributions of Loops A, B, and C to Glycine Sensitivity at β+/α− Interface

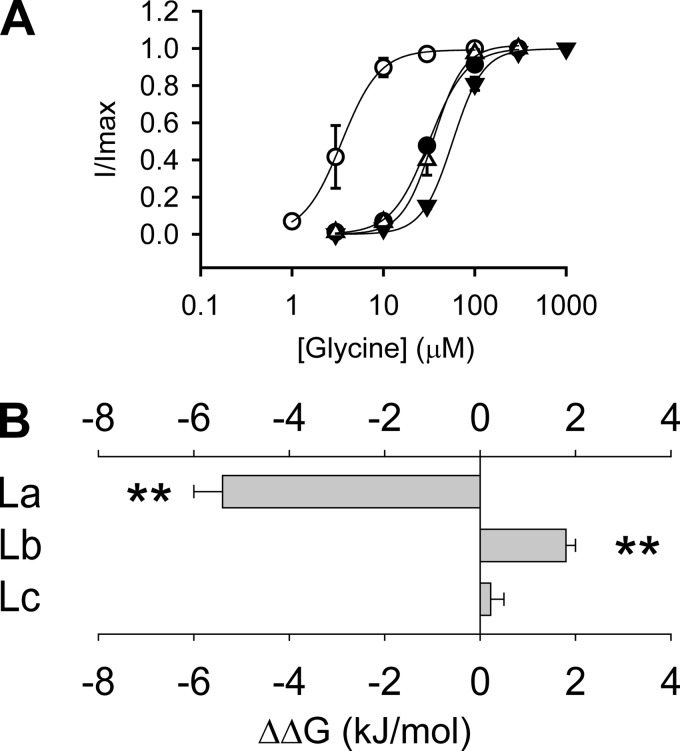

To compare the glycine sensitivities of the β+/α− and α+/α− interfaces, we created three chimeric GlyRs by replacing loop A, B, or C in the α GlyR with the corresponding loop from the β subunit. These chimeras were named αChLa, αChLb, and αChLc GlyRs, respectively (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. 1). Electrophysiological recording demonstrated that the αChLa GlyR (EC50 3.7 ± 0.9 μm) was 8.9 ± 2.2 times more sensitive (p < 0.01) to glycine than the α GlyR (EC50 33 ± 2 μm) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The EC50 is a reflection of the binding and gating abilities of an agonist (31), and therefore, the higher glycine sensitivity of the αChLa GlyR implies that loop A from the β+/α− interface contributes more binding/gating energy than the corresponding loop from the α+/α− interface. In contrast, the αChLb GlyR (EC50, 69 ± 6 μm) demonstrated a glycine sensitivity 2.1 ± 0.2 times lower (p < 0.01) than that of the α GlyR (Fig. 2A and Table 1), implying that loop B from the β+/α− interface contributes less binding/gating energy than that from the α+/α− interface. To facilitate comparison of the relative contribution of each loop to agonist binding/gating energy, we set the energy level of the α GlyR at 0. The binding/gating energy levels of other constructs were then calculated relative to the α GlyR (ΔΔG). The relative glycine binding/gating energies of loops A, B, and C from the β+/α− interface were −5.4 ± 0.6 (significantly <0, p < 0.01), 1.8 ± 0.3 (significantly >0, p < 0.01) and 0.22 ± 0.32 kJ/mol (not significantly different from 0, p > 0.05) (Fig. 2B and Table 1), respectively.

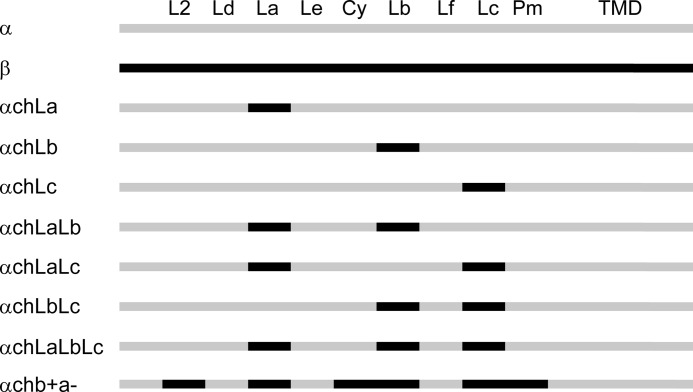

FIGURE 1.

Chimera construction of the GlyR α1 and β subunits. Sequences of GlyR α1 and β subunits are in gray and black, respectively. The abbreviations are as follows: L2, loop 2; Ld, loop D; La, loop A; Le, loop E; Cy, Cys-loop; Lb, loop B; Lf, loop F; Lc, loop C; Pm, pre-M1; TMD, transmembrane domain.

FIGURE 2.

Relative contributions of loops A, B, and C to glycine sensitivity at the β+/α− interface. A, averaged normalized glycine dose-response curves for the α1WT (●), αChLa (○), αChLb (▾), and αChLc (Δ) GlyRs. B, the glycine binding/gating energies contributed by loop A (La), B (Lb), and C (Lc) from the β+/α− interface, relative to the homologous loops in the α+/α− interface of the α1 GlyR (**, p < 0.01 using Student's t test). Note that the glycine dose-response curve for the α1WT is reproduced from Shan et al. (41).

TABLE 1.

Properties of glycine- and taurine-induced currents of GlyRs recorded in HEK293 cells

Note that partial values for the glycine-induced current of the α GlyR are reproduced from Shan et al. (41).

| Constructs | Glycine |

Taurine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | ΔΔG | nH | n | EC50 | ΔΔG | nH | Imax, Tau/Imax, Gly | n | |

| μm | kJ/mol | μm | kJ/mol | % | |||||

| α | 33 ± 2 | 0 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 4 | 362 ± 59 | 0 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 99 ± 0 | 4 |

| αChLa | 3.7 ± 0.9 | −5.4 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 4 | 53 ± 9 | −4.8 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 100 ± 0 | 4 |

| αChLb | 69 ± 6 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 4 | 584 ± 164 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 99 ± 2 | 4 |

| αChLc | 36 ± 4 | 0.22 ± 0.32 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 4 | 720 ± 149 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 73 ± 6 | 4 |

| αChLaLb | 30 ± 3 | −0.24 ± 0.30 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 4 | 134 ± 23 | −2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 0 | 4 |

| αChLaLc | 8.4 ± 1.7 | −3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 4 | 220 ± 56 | −1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 99 ± 1 | 4 |

| αChLbLc | 31 ± 5 | −0.15 ± 0.43 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 4 | 436 ± 126 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 78 ± 7 | 4 |

| αChLaLbLc | 4.7 ± 0.7 | −4.8 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 4 | 102 ± 26 | −3.1 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 94 ± 2 | 4 |

| αChL2CyPm | 54 ± 10 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 4 | 523 ± 139 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 85 ± 6 | 4 |

| αChb+a− | 3.7 ± 0.4 | −5.4 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 4 | 80 ± 13 | −3.7 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 100 ± 0 | 4 |

Interactions between Loops A, B, and C Affect Glycine Binding/Gating

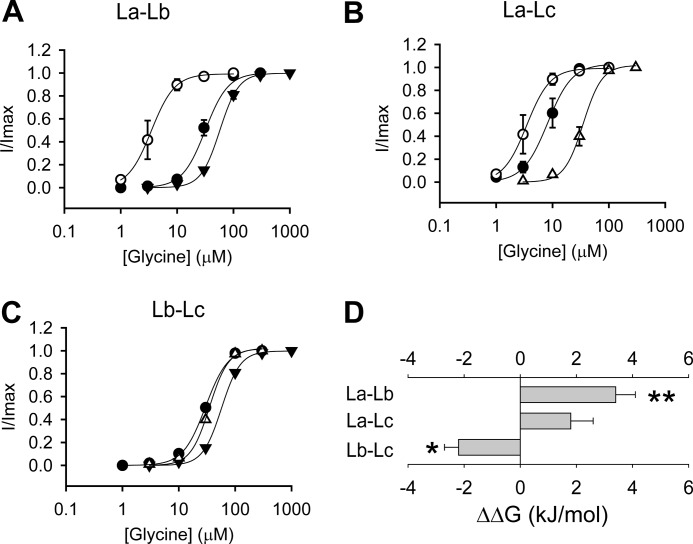

Previous investigations based on crystal structures and mutation/modeling of the Cys-loop receptors have shown that the agonist binds to the ECD subunit interface through the interaction between specific moieties of agonist molecules and specific amino acids of loops A, B, C, D, E, and F (32–34). In such a mode, it has been assumed that each loop contributes independently to agonist binding/gating energy. However, when we introduced both loops A and B from the GlyR β subunit into the α GlyR (αChLaLb GlyR) (Fig. 1), it demonstrated a glycine EC50 value of 30 ± 3 μm and a relative agonist binding/gating energy value of −0.24 ± 0.30 kJ/mol (Fig. 3A and Table 1). Surprisingly, this energy value was not simply the addition of the energy values of αChLa and αChLb GlyRs (Fig. 3A and Table 1). We thus concluded that an energetic interaction existed between loops A and B. The interaction energy was expressed as ΔΔG (interaction) = ΔΔG (αChLaLb GlyR) − ΔΔG (αChLa GlyR) − ΔΔG (αChLb GlyR). This value was calculated to be 3.4 ± 0.7 kJ/mol between loops A and B, which was significantly higher than 0 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3D). A positive value of interaction energy implies a negative cooperation between loops A and B in contributing to agonist binding/gating. Similar electrophysiological characterizations and calculations were also applied to chimeric α GlyRs containing both loops A and C (αChLaLc GlyR) (Figs. 1 and 3B), and both loops B and C (αChLbLc GlyR) (Figs. 1 and 3C), from the β subunit. The respective interaction energies were 1.8 ± 0.8 kJ/mol (not significantly different from 0, p > 0.05) and −2.2 ± 0.6 kJ/mol (significantly <0, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3D). These results indicated a positive cooperation exists between loops B and C in contributing to glycine binding/gating.

FIGURE 3.

Interactions between loops A, B, and C at the β+/α− interface. A, averaged normalized glycine dose-response curves for the αChLa (○), αChLb (▾), and αChLaLb (●) GlyRs. B, averaged normalized glycine dose-response curves for the αChLa (○), αChLc (Δ), and αChLaLc (●) GlyRs. C, averaged normalized glycine dose-response curves for the αChLb (▾) and αChLc (Δ) and αChLbLc (●) GlyRs. D, Interaction energy between loops A and B (La–Lb), loops A and C (La–Lc), and loops B and C (Lb–Lc) (*, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 using Student's t test). The interaction energy is calculated, for instance between loops A and B, using the formula ΔΔG (interaction) = ΔΔG (αChLaLb GlyR) − ΔΔG (αChLa GlyR) − ΔΔG (αChLb GlyR).

Agonist Sensitivity of β+/α− Interface

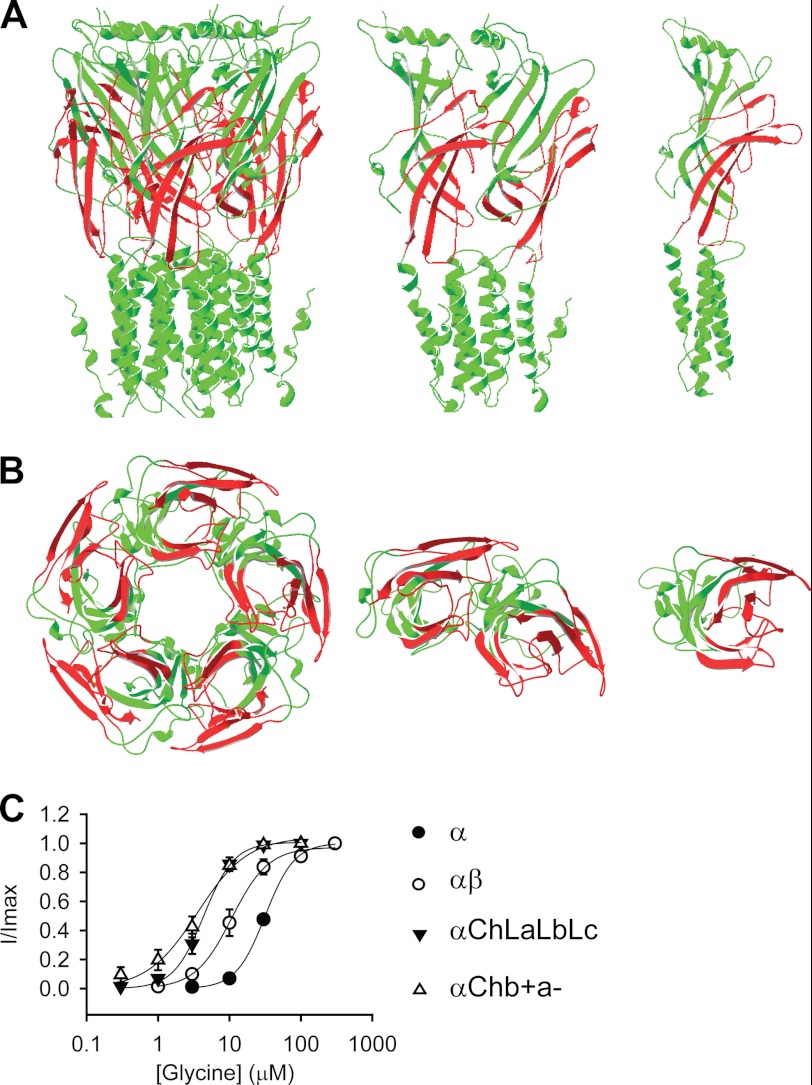

The αChLaLbLc GlyR was constructed by introducing loops A, B, and C from the GlyR β subunit together into the α GlyR. This homomeric chimeric GlyR thus incorporated the (+) side of the β subunit and the (−) side of the α subunit at its agonist-binding pockets, mimicking those existing at the β+/α− interfaces in the heteromeric αβ GlyR. Therefore, we hypothesized that this construct would report the properties of the β+/α− interfaces in the αβ GlyR. This construct demonstrated a glycine EC50 value of 4.7 ± 0.7 μm (Fig. 4C and Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Agonist sensitivity of the β+/α− interface. A and B, structural models of the αChb+a− GlyR. Green and red represent sequences from the GlyR α1 and β subunits, respectively. A, side views of the pentamer, dimer, and monomer (from left to right). B, bottom views looking from the intracellular side of the pentamer, dimer, and monomer (from left to right). (The transmembrane domains are truncated in the bottom views for clarity.) C, averaged normalized glycine dose-response curves for indicated GlyRs. Note that the GlyR structure model is adapted from Lynagh et al. (40), and the glycine dose-response curves for the α and αβ GlyRs are reproduced from Shan et al. (41) and Shan et al. (26), respectively.

However, other loops apart from loops A–F, such as loop 2, the Cys-loop, and the pre-M1 linker also exist in the (+) side of the ECD subunit interface. Although these domains do not participate in agonist binding, they mediate channel gating (32–34). To faithfully report the agonist binding/gating properties of the β+/α− interface, we therefore next introduced loop 2, the Cys-loop, and the pre-M1 linker from the β subunit into the αChLaLbLc GlyR (Fig. 1 and Fig. 4, A and B). This construct, named αChb+a− GlyR, exhibited a glycine sensitivity comparable to the αChLaLbLc GlyR (EC50 3.7 ± 0.4 μm for αChb+a− GlyR versus 4.7 ± 0.7 μm for αChLaLbLc GlyR, Fig. 4C and Table 1). Consistently, a control construct, the αChL2CyPm GlyR, where only loop 2, the Cys-loop, and the pre-M1 linker from the β subunit were introduced into the α GlyR, exhibited a glycine sensitivity comparable with that of the α GlyR (αChL2CyPm GlyR EC50 = 54 ± 10 μm, Table 1). This implies that loop 2, the Cys-loop, and the pre-M1 linker from the β+/α− interface contribute to the gating to an extent similar to that of the α +/α− interface.

Both the αChb+a− and αChLaLbLc GlyRs demonstrated much higher sensitivity toward glycine than the α GlyR (EC50 = 33 ± 2 μm, p < 0.01, Fig. 4C, and Table 1), implying that the β+/α− interface might have a higher glycine binding/gating ability than the α+/α− interface. It is worth noting that the glycine sensitivities of both the αChLaLbLc and αChb+a− GlyRs were also higher than that of the heteromeric αβ GlyR (11 ± 2.4 μm, both p < 0.05) (26). The αβ GlyR agonist binding sites are supposed to be formed by, at least, β+/α− and α+/β− interfaces (19). The glycine sensitivity of the αβ GlyR might thus be a mixture of the high sensitivity of the β+/α− interfaces and the relatively low sensitivity of the α+/β− interfaces.

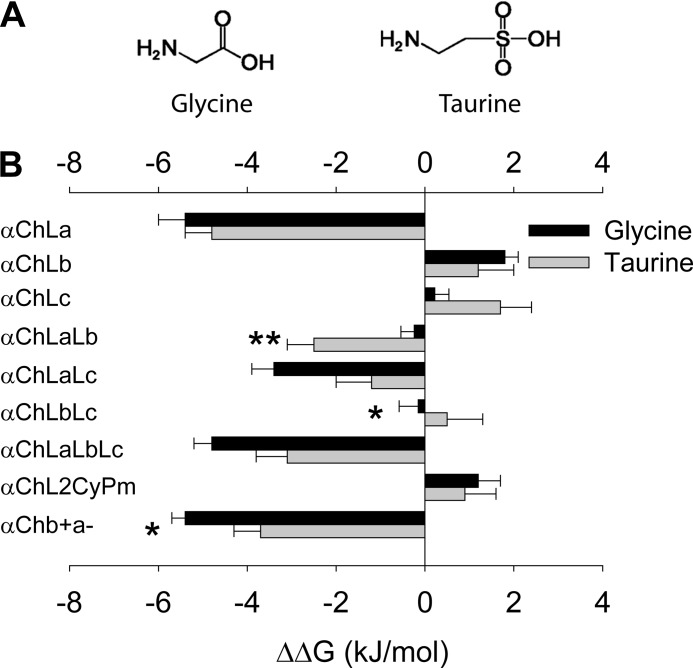

Glycine and Taurine Interact Differently with ECD Loops

Taurine also is an agonist of the GlyR, with a lower affinity and efficacy than glycine (35). Taurine has a structure that is slightly different from that of glycine (Fig. 5A), and therefore, the mode of its interaction with each binding loop of the β+/α− interface and the subsequent gating process might be different from that of glycine. To test this hypothesis, we examined the taurine EC50 values of all the constructs described above (Table 1). The relative agonist binding/gating energy was calculated in the same way as for glycine. After comparing the relative agonist binding/gating energies between taurine and glycine (Fig. 5B), we found that loops A and B together from the β+/α− interface rendered relatively more binding/gating energy for taurine than for glycine (ΔΔG of αChLaLb: −2.5 ± 0.6 kJ/mol for taurine versus −0.24 ± 0.30 kJ/mol for glycine, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5B and Table 1). In contrast, loops B and C together from the β+/α− interface rendered relatively less binding/gating energy for taurine than for glycine (ΔΔG of αChLbLc, 0.5 ± 0.8 kJ/mol for taurine versus −0.15 ± 0.43 kJ/mol for glycine; p < 0.05) (Fig. 5B and Table 1). The overall β+/α− interface contributed a slightly less binding/gating energy to taurine than to glycine (ΔΔG of αChb+a−, −3.8 ± 0.6 kJ/mol for taurine versus −5.4 ± 0.3 kJ/mol for glycine; p < 0.05) (Fig. 5B and Table 1). These data suggest that loops at the (+) side of the β+/α− interface contribute to agonist binding/gating to different extents for taurine and glycine.

FIGURE 5.

Differential relative contributions of loops at the β+/α− interface to glycine and taurine binding/gating energies. A, structural formulae of glycine and taurine. B, relative glycine and taurine binding/gating energies of indicated constructs (*, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 using Student's t test).

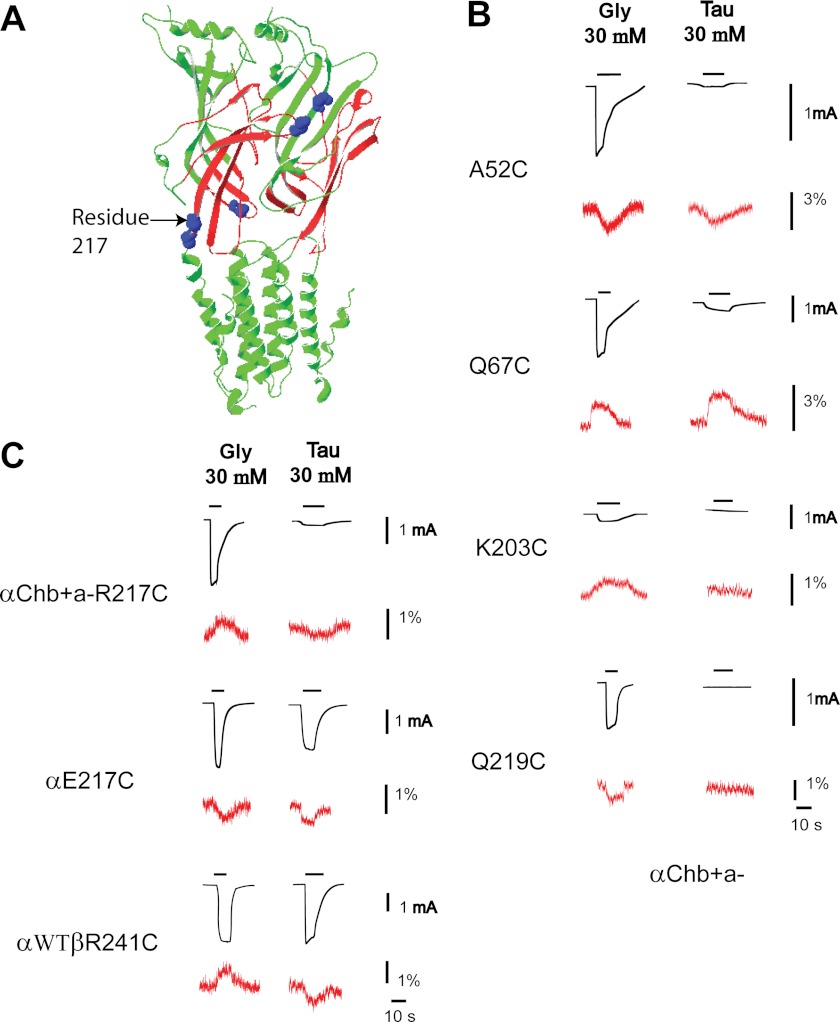

Conformational Changes Induced by Agonist Binding to β+/α− Interfaces in αChb+a− GlyR

We next sought to compare conformational changes induced by agonist binding to β+/α− and α+/α− interfaces by using the VCF technique. VCF detects local conformational changes in the vicinity of a residue that has been covalently labeled with an environmentally sensitive fluorescent dye (36, 37). Rhodamine fluorescent dyes are usually used because rhodamine fluorescence exhibits an increase in quantum efficiency as the hydrophobicity of its environment is increased. Thus, fluorescence intensity reports a change of hydrophobicity of its immediate microenvironment, which is often caused by local conformational changes.

Previously, we characterized conformational changes upon agonist binding at the α+/α− interface in the homomeric α GlyR (28, 29). To achieve this, we mutated representative residues from loops C, D, E, and F, loop 2 and the pre-M1 linker to cysteine, covalently labeled them with various rhodamine fluorescent dyes and then simultaneously measured ligand-induced current and fluorescence responses. The labeled receptors demonstrate changes in fluorescence upon the application of glycine and taurine (28, 29). These changes in fluorescence reflected conformational changes experienced at the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR upon agonist binding.

Following the same strategy, we introduced cysteine mutations to several residues at the β+/α− interface in the αChb+a− GlyR, at locations homologous to those we previously examined in the α+/α− interface in α GlyRs (28, 29) (Fig. 6A). These cysteine mutant αChb+a− GlyRs were labeled with the same dyes used for their respective homologous residues at the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR (28, 29) and subjected to VCF examination. As shown in Fig. 6B and Table 2, a saturating concentration of glycine generally induced fluorescence changes that were in the same direction (i.e. increase or decrease) as those previously measured at the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR (28, 29). The only exception was the 217 residue in the pre-M1 linker. At the α+/α− subunit interface, glycine application induced a decrease in fluorescence changes in the TMRM-labeled α E217C GlyR (Fig. 6C and Table 2), implying that the hydrophobicity was decreased in the vicinity of this residue upon glycine binding. In contrast, at the β+/α− subunit interface, glycine application induced a fluorescence increase in the TMRM-labeled αChb+a− R217C GlyR, implying that the hydrophobicity was increased in the vicinity of this residue upon glycine binding.

FIGURE 6.

VCF data of selective residues at the β+/α− interface. A, residues investigated are mapped onto the structural model of the β+/α− interface. B, current and VCF changes of indicated αChb+a− GlyR constructs, upon glycine and taurine applications. C, current and VCF changes of the 217 (or homologous residue 241 in the β subunit) cysteine mutants of the αChb+a−, α, and αβ GlyRs, upon glycine and taurine applications. Traces in black represent current changes, whereas traces in red represent fluorescence changes. Note that the GlyR structure model is adapted from Lynagh et al. (40).

TABLE 2.

Properties of glycine- and taurine-induced currents and fluorescences of rhodamine fluorescent dye-labeled GlyRs recorded in oocytes

| Constructs | Dye | Glycine (30 mm) |

Taurine (30 mm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imax | Fmax | n | Imax | Fmax | n | ||

| μA | % | μA | % | ||||

| αChb+a− A52C | MTS-TAMRA | 1.23 ± 0.18 | −2.69 ± 0.26 | 5 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | −1.76 ± 0.24 | 3 |

| αChb+a− Q67C | MTS-TAMRA | 2.63 ± 0.22 | 1.85 ± 0.18 | 5 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 2.31 ± 0.15 | 4 |

| αChb+a− K203C | MTS-TAMRA | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.01 | 4 | −a | − | 3 |

| αChb+a− R217C | TMRM | 3.10 ± 0.49 | 1.55 ± 0.41 | 5 | 0.04 ± 0.007 | −0.79 ± 0.11 | 5 |

| αChb+a− Q219C | MTSR | 0.82 ± 0.31 | −1.48 ± 0.02 | 4 | − | − | 4 |

| α E217C | TMRM | 2.17 ± 0.33 | −1.18 ± 0.12 | 4 | 1.88 ± 0.22 | −1.07 ± 0.15 | 4 |

| αWT β R241C | TMRM | 4.37 ± 0.27 | 1.20 ± 0.10 | 5 | 3.56 ± 0.19 | −1.09 ± 0.19 | 5 |

a −, no signal was detected.

We also examined conformational changes of the β+/α− subunit interface upon application of taurine. As shown in Fig. 6B, a saturating concentration of taurine induced fluorescence changes, if could be detected, in the same direction (i.e. increase or decrease) as observed at the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR (28, 29). Surprisingly, the labeled 217 residue at the β+/α− interface detected a decrease in fluorescence upon taurine application, which is opposite to that found when glycine was applied (Fig. 6C). This is reminiscent of responses found at the labeled M2–M3 loop residue, L274C, in the α GlyR (30). L274C, when labeled with TMRM and subjected to VCF examination, demonstrated an increase in fluorescence upon glycine application and a decrease in fluorescence upon taurine application. Our data suggest that different agonists induce distinct conformational changes not only in the M2–M3 domain (residue 274) but also in the pre-M1 linker (residue 217). Interestingly, both the M2-M3 domain and pre-M1 linker are components of the transition zone, which is located physically between the extracellular agonist binding domain and the transmembrane channel pore and functionally mediates the agonist binding information flow to the channel gate. Therefore, it might be a common phenomenon that residues in the transition zone experience distinct conformational changes in response to the binding of glycine and taurine.

Conformational Changes Induced by Agonist Binding to β+/α− Interfaces in αβ GlyR

Because the 217 residue at the β+/α− interface in the αChb+a− GlyR demonstrated a distinct VCF pattern from the 217 residue at the α+/α− interface in the α GlyR, we wondered whether this pattern could be duplicated in the heteromeric αβ GlyR. We mutated residue β241, which is homologous to residue α217, in the heteromeric αβ GlyR (αWTβR241C GlyR) and labeled it with TMRM. This construct exhibited a fluorescence increase upon glycine application and a fluorescence decrease upon taurine application (Fig. 6C). This is the same pattern as found in the αChb+a− 217C GlyR (Fig. 6C), confirming that the αChb+a− GlyR recapitulates conformational changes that occur at the β+/α− interface of the heteromeric αβ GlyR.

DISCUSSION

Universal Strategy to Examine Heteromeric Subunit Interface

The revelation of crystal structures of various Cys-loop receptors in the past decade has revolutionized research in investigating the structure and function of the Cys-loop receptors. Here, by exploiting this information, we reconstituted the heteromeric GlyR β+/α− interface in a homomeric GlyR (αChb+a− GlyR). This provides a universal strategy for unambiguously examining a heteromeric subunit interface by functional assay. Previously, the agonist sensitivity of the α+/γ− and α+/δ− subunit interfaces of the nAChR were examined either by expressing αγ or αδ dimers or by expressing α2βγ2 or α2βδ2 pentamers (38, 39). However, this cannot be a universal strategy for characterizing heteromeric subunit interfaces. For example, in the αβ GlyR, where the putative stiochiometry is α2β3 (19), at least two types of agonist-binding interfaces, the β+/α− and α+/β−, could form when both subunits are co-expressed. Therefore, the strategy used for the nAChR as described above would not be applicable to the GlyR. However, the strategy we propose here, i.e. reconstituting a heteromeric subunit interface in a homomeric receptor, is not only universally applicable for examining any subunit interface, but is also suitable for traditional functional assays such as electrophysiological recording, because the final construct still remains as a functional channel. It should be noted that this methodology is limited by the availability of a functional homomeric protein, where the heteromeric interface is to be reconstituted.

GlyR β+/α− Subunit Interface Exhibits Distinct Properties from α+/α− Subunit Interface

By examining the αChb+a− GlyR where the β+/α− subunit interface is hosted in a homomeric GyR using electrophysiological recording, we determined its agonist sensitivity. Both glycine and taurine demonstrated sensitivity at this interface higher than those at the α+/α− interface (8.9 and 4.5 times for glycine and taurine, respectively, Figs. 4 and 5 and Table 1). This might explain the finding that the glycine sensitivity of the αβ GlyR (EC50 = 11 ± 2 μm) (26) is slightly higher than that of the α GlyR (EC50 = 33 ± 2 μm). It should be noted that the key residues contributing to agonist binding, which were determined previously (β Glu180/α Glu157, β Lys223/α Lys200, β Tyr225/α Tyr202, β Thr228/α Thr204, β Tyr231/α Phe207, and β Thr232/α Thr208) from the + side are conserved between the β+/α− and α+/α− subunit interfaces (19, 32). Note that the key residues from the − side are not discussed here because both β+/α− and α+/α− subunit interfaces share the same α− side. Therefore, the difference in agonist sensitivity must arise from the contribution of other residues that presumably play relatively minor roles in binding/gating. These residues could presumably induce alterations in loop structure, which leads to a change in the binding/gating energies of the conserved key residues.

A detailed functional characterization of the GlyR β+/α− subunit interface indicated that its higher agonist sensitivity is primarily due to loop A. Loop A from the GlyR β+/α− subunit interface showed 8.9 and 6.8 times higher sensitivity toward glycine and taurine, respectively, than that from the α+/α− subunit interface. In contrast, both loops B and C had relatively minor effects on agonist sensitivities (Figs. 2 and 5 and Table 1). Surprisingly, individual loops did not affect agonist binding/gating independently. We showed that significant negative cooperation exists between loops A and B, whereas positive cooperation exists between loops B and C for contributing to the agonist binding/gating (Fig. 3). This may not be surprising, considering that all the loops converge into the agonist-binding cavity and direct physical interaction might exist between them (6–8).

Taken together, the β+/α− interface exhibited agonist-binding/gating properties distinct from those of the α+/α− interface. This must have arisen from different conformations of the β+/α− and α+/α− subunit interfaces. This hypothesis was verified by VCF. The 217 residue (α subunit numbering) exhibited fluorescence changes upon glycine application that were opposite in direction at the β+/α− and α+/α− subunit interfaces (Fig. 6), implying distinct dynamic conformational changes upon agonist binding in the β+/α− subunit interface, compared with the α+/α− subunit interface.

Although the β+/α− interface exhibits properties distinct from those of the α+/α− interface for both glycine and taurine, it does not contribute to both glycine and taurine binding/gating to the same extent (Fig. 5). This phenomenon was also reflected in a dynamic mode revealed through a VCF examination. The 217 residue in the β+/α− interface indicated fluorescence changes in opposite directions upon glycine and taurine applications (Fig. 6). Moreover, this distinct pattern was also duplicated in the heteromeric αβ GlyR (Fig. 6), which confirms that the αChb+a− GlyR reconstitutes structural components and recapitulates functional properties, of the β+/α− interface in the heteromeric αβ GlyR.

Use of Heteromeric Subunit Interface Reconstituted in Homomeric Protein

A homomeric protein hosting heteromeric subunit interfaces would be useful for unambiguously characterizing heteromeric subunit interfaces, as described above. This characterization would provide information for interface-specific drug design.

Currently, one of the major problems in clinical drugs is lack of specificity, partially because most proteins mediate many functions. For example, GABAARs are distributed widely throughout the central nervous system and involved in many neural functions. A GABAAR-targeting drug that attempts to correct one neural function could interfere with many other neural functions as well. Fortunately, GABAARs are constructed from a total of 19 subunits, and certain combinations have a limited distribution and are thus likely to have a restricted functional role (2, 3). Currently GABAAR subtype-specific drugs are being pursued. Although this strategy would render specificity to certain extent, it might not be enough. (For example, the GABAAR α1 subtype universally distributes in the central nervous system.) As one subtype, by combining with various other subtypes, could form many types of interfaces, interface-specific drugs would potentially render more specificity. The system we report here, i.e. reconstituting a heteromeric subunit interface in a homomeric protein, is an ideal tool for screening for subunit interface-specific drugs.

These subunit interface-specific drugs would be useful not only for clinical medicine, but also for basic physiological research. For example, although subtypes of Cys-loop receptors existing in certain brain regions can be readily identified currently, the exact stoichiometry of native receptors cannot. It should be noted that native receptors only exist in few among many possible combinations of available subtypes (1–5). Therefore, the exact stoichiometry of native receptors must be determined experimentally. Subunit interface-specific drugs can be used as tools to detect whether given subunit interfaces exist and in consequence to determine the overall stoichiometry.

In addition, the homomeric protein hosting a heteromeric subunit interface could also be used for raising subunit interface-specific antibodies. Such antibodies could subsequently be used to detect not only the existence, but also the distribution, of certain subunit interface-containing proteins. This information would provide a precise morphological, physiological, and pharmacological profile for certain brain areas and eventually contribute to the design of drugs with high specificity.

Acknowledgment

We thank B. A. Cromer (RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia) for kindly sharing the structural model of the GlyR α1 subunit.

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1, data, and an additional reference.

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- GlyR

- glycine receptor

- GABAAR

- the type A γ-aminobutyric acid receptor

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- VCF

- voltage-clamp fluorometry

- MTS-TAMRA

- 2-((5(6)-tetramethylrhodamine) carboxylamino)ethyl methanethiosulfonate

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine-6-maleimide

- MTSR

- rhodamine methanethiosulfonate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Taly A., Corringer P. J., Guedin D., Lestage P., Changeux J. P. (2009) Nicotinic receptors: Allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 733–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olsen R. W., Sieghart W. (2008) International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: Classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 60, 243–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olsen R. W., Sieghart W. (2009) GABA A receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology 56, 141–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnes N. M., Hales T. G., Lummis S. C., Peters J. A. (2009) The 5-HT3 receptor–the relationship between structure and function. Neuropharmacology 56, 273–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lynch J. W. (2009) Native glycine receptor subtypes and their physiological roles. Neuropharmacology 56, 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brejc K., van Dijk W. J., Klaassen R. V., Schuurmans M., van Der Oost J., Smit A. B., Sixma T. K. (2001) Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 411, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 967–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hibbs R. E., Gouaux E. (2011) Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature 474, 54–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2009) Structure of a potentially open state of a proton-activated pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature 457, 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bocquet N., Nury H., Baaden M., Le Poupon C., Changeux J. P., Delarue M., Corringer P. J. (2009) X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature 457, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2008) X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature 452, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee W. Y., Free C. R., Sine S. M. (2009) Binding to gating transduction in nicotinic receptors: Cys-loop energetically couples to pre-M1 and M2-M3 regions. J. Neurosci. 29, 3189–3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bouzat C., Gumilar F., Spitzmaul G., Wang H. L., Rayes D., Hansen S. B., Taylor P., Sine S. M. (2004) Coupling of agonist binding to channel gating in an ACh-binding protein linked to an ion channel. Nature 430, 896–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lummis S. C., Beene D. L., Lee L. W., Lester H. A., Broadhurst R. W., Dougherty D. A. (2005) Cis-trans isomerization at a proline opens the pore of a neurotransmitter-gated ion channel. Nature 438, 248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karlin A., Akabas M. H. (1995) Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron 15, 1231–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duncalfe L. L., Carpenter M. R., Smillie L. B., Martin I. L., Dunn S. M. (1996) The major site of photoaffinity labeling of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor by [3H]flunitrazepam is histidine 102 of the α subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 9209–9214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kucken A. M., Wagner D. A., Ward P. R., Teissére J. A., Boileau A. J., Czajkowski C. (2000) Identification of benzodiazepine binding site residues in the γ2 subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 932–939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buhr A., Baur R., Malherbe P., Sigel E. (1996) Point mutations of the α1 β2 γ2 γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor affecting modulation of the channel by ligands of the benzodiazepine binding site. Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 1080–1084 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grudzinska J., Schemm R., Haeger S., Nicke A., Schmalzing G., Betz H., Laube B. (2005) The β subunit determines the ligand binding properties of synaptic glycine receptors. Neuron 45, 727–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramerstorfer J., Furtmüller R., Sarto-Jackson I., Varagic Z., Sieghart W., Ernst M. (2011) The GABAA receptor α+β− interface: a novel target for subtype selective drugs. J. Neurosci. 31, 870–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sieghart W., Ramerstorfer J., Sarto-Jackson I., Varagic Z., Ernst M. (2012) A novel GABA(A) receptor pharmacology: Drugs interacting with the α+ β− interface. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 476–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liman E. R., Tytgat J., Hess P. (1992) Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron 9, 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shan Q., Lynch J. W. (2010) Chimera construction using multiple template-based sequential PCRs. J. Neurosci. Methods 193, 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lynch J. W., Han N. L., Haddrill J., Pierce K. D., Schofield P. R. (2001) The surface accessibility of the glycine receptor M2–M3 loop is increased in the channel open state. J. Neurosci. 21, 2589–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vogel N., Kluck C. J., Melzer N., Schwarzinger S., Breitinger U., Seeber S., Becker C. M. (2009) Mapping of disulfide bonds within the amino-terminal extracellular domain of the inhibitory glycine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36128–36136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shan Q., Han L., Lynch J. W. (2011) β Subunit M2–M3 loop conformational changes are uncoupled from α1 β glycine receptor channel gating: Implications for human hereditary hyperekplexia. PLoS ONE 6, e28105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shan Q., Haddrill J. L., Lynch J. W. (2001) A single β subunit M2 domain residue controls the picrotoxin sensitivity of αβ heteromeric glycine receptor chloride channels. J. Neurochem. 76, 1109–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pless S. A., Lynch J. W. (2009) Magnitude of a conformational change in the glycine receptor β1–β2 loop is correlated with agonist efficacy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27370–27376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pless S. A., Lynch J. W. (2009) Ligand-specific conformational changes in the α1 glycine receptor ligand-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15847–15856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pless S. A., Dibas M. I., Lester H. A., Lynch J. W. (2007) Conformational variability of the glycine receptor M2 domain in response to activation by different agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36057–36067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colquhoun D. (1998) Binding, gating, affinity, and efficacy: The interpretation of structure-activity relationships for agonists and of the effects of mutating receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125, 924–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lynch J. W. (2004) Molecular structure and function of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiol. Rev. 84, 1051–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miller P. S., Smart T. G. (2010) Binding, activation, and modulation of Cys-loop receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson A. J., Lester H. A., Lummis S. C. (2010) The structural basis of function in Cys-loop receptors. Q. Rev. Biophys. 43, 449–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lewis T. M., Schofield P. R., McClellan A. M. (2003) Kinetic determinants of agonist action at the recombinant human glycine receptor. J. Physiol. 549, 361–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gandhi C. S., Isacoff E. Y. (2005) Shedding light on membrane proteins. Trends Neurosci. 28, 472–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pless S. A., Lynch J. W. (2008) Illuminating the structure and function of Cys-loop receptors. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 35, 1137–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blount P., Merlie J. P. (1989) Molecular basis of the two nonequivalent ligand binding sites of the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron 3, 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sine S. M., Claudio T. (1991) γ- and δ-subunits regulate the affinity and the cooperativity of ligand binding to the acetylcholine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19369–19377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lynagh T., Webb T. I., Dixon C. L., Cromer B. A., Lynch J. W. (2011) Molecular determinants of ivermectin sensitivity at the glycine receptor chloride channel. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43913–43924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shan Q., Han L., Lynch J. W. (2012) Function of hyperekplexia-causing α1R271Q/L glycine receptors is restored by shifting the affected residue out of the allosteric signaling pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 2113–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]