Background: Elongator is a multiprotein complex that exhibits acetyltransferase activity.

Results: In the subcomplex Elp4–6, Elp6 acts as a bridge to assemble Elp4 and Elp5, and each subunit adopts a similar RecA-ATPase-like fold.

Conclusion: Subcomplex Elp4–6 forms a hexameric ring-shaped structure that is important for histone H3 binding.

Significance: This finding may shed light on holo-Elongator complex assembly and its substrate recognition.

Keywords: Chromatin Remodeling, Epigenetics, Histone Acetylase, Protein Crystallization, Transcription Elongation Factors, Elongator Complex, Elp4–6, Protein Complex Assembly, RNA Polymerase II, Ring-shaped Structure

Abstract

Elongator is a multiprotein complex composed of two subcomplexes, Elp1–3 and Elp4–6. Elongator is highly conserved between yeast and humans and plays an important role in RNA polymerase II-mediated transcriptional elongation and many other processes, including cytoskeleton organization, exocytosis, and tRNA modification. Here, we determined the crystal structure of the Elp4–6 subcomplex of yeast. The overall structure of Elp4–6 revealed that Elp6 acts as a bridge to assemble Elp4 and Elp5. Detailed structural and sequence analyses revealed that each subunit in the Elp4–6 subcomplex forms a RecA-ATPase-like fold, although it lacks the key sequence signature of ATPases. Site-directed mutagenesis and biochemical analyses indicated that the Elp4–6 subcomplex can assemble into a hexameric ring-shaped structure in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, GST pulldown assays showed that the ring-shaped assembly of the Elp4–6 subcomplex is important for its specific histone H3 binding. Our results may shed light on the substrate recognition and assembly of the holo-Elongator complex.

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, transcript elongation through nucleosomes by RNA polymerase II is regulated by reorganization of the chromatin template (1, 2). The dynamics of chromatin reorganization are tightly regulated via multiple mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling, histone eviction, variant incorporation, and histone modifications such as acetylation/deacetylation, phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, and methylation/demethylation (3–5). Histone acetylation typically is correlated with transcription activity and usually is carried out by a variety of histone acetyltransferase complexes (6, 7). Elongator, which is responsible for histone acetyltransferase activities, was initially identified from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for its tight association with the hyperphosphorylated, elongated form of RNA polymerase II and was therefore thought to function during transcript elongation (8).

Holo-Elongator is a six-subunit assembly composed of two subcomplexes; its core consists of Elp1, -2, and -3 (8), and the accessory is composed of Elp4, -5, and -6 (9–11). Within the Elongator complex, the largest subunit, Elp1, is considered to primarily function as a scaffold protein that is required for formation of the complex (12), Mutations in human IKBKAP, which encodes ELP1, are associated with familial dysautonomia (14, 15). Elp2 does not appear to have any scaffolding function, as the remaining complex is able to form in its absence (13). The Elp3 subunit of the Elongator complex contains a histone acetyltransferase of the GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase family and has been shown to acetylate histones and α-tubulin, which are involved in gene transcription (16–19) and cellular motility (20, 21), respectively. In addition, Elp3 contains an iron-sulfur cluster that can bind S-adenosylmethionine (22) and may be involved in DNA demethylation (23). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was shown recently to be linked to allelic variants of ELP3 (24). Based on sequence comparisons, it was suggested that Elp4 and Elp6 could be inactive orthologues of ancestral ATPases involved in chromatin remodeling (25). In S. cerevisiae, deletions of the individual genes that encode the Elongator subcomplex Elp4–6 revealed that only the ELP5 gene is essential for growth (11). However, the mammalian ELP4 gene was recently implicated in rolandic epilepsy (26) and the eye anomaly aniridia (27–29).

Except for its lysine acetyltransferase activity (17, 20, 21, 30–32), Elongator has been associated with other functions of tRNA processing (33, 34) and exocytosis (35). Holo-Elongator, containing all six subunits, is a functional unit, as illustrated in yeast where strains lacking any of the six Elp proteins exhibit similar phenotypes (8, 9, 11). In addition, removal of almost any of the Elongator subunits affects interactions of the other subunits and the lysine acetyltransferase activity of Elongator (12, 17, 36, 37).

Elongator is an evolutionarily highly conserved complex (19, 21, 31, 32, 38). However, the molecular mechanism of Elongator complex assembly is unclear. Here, we report the crystal structure of the yeast Elongator subcomplex Elp4–6 and provide insight into the substrate recognition and assembly of the holo-Elongator complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

Gene fragments corresponding to yeast Elp4 (residues 67–372 from full-length residues 1–456) (yElp4), Elp5 (residues 1–238 from full-length residues 1–309) (yElp5), and full-length Elp6 (residues 1–273) (yElp6) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the S. cerevisiae genome. The DNA fragment of yElp4 was cloned into the pET32a vector (Novagen). The S-tag and thrombin recognition sites were replaced with a sequence encoding a 3C protease-cleavable segment (Leu-Glu-Val-Leu-Phe-Gln-Gly-Pro). The DNA fragments of yElp5 and yElp6 were cloned into the pETDuet-1 (Novagen) vector to co-express these two proteins. All point mutations of the yElp4–6 subcomplex described here were created using a standard PCR-based mutagenesis method and confirmed using DNA sequencing. All resulting proteins contained Trx-His6 tags at their N termini.

BL21(DE3) pUBS520 Escherichia coli cells harboring the expression plasmid were grown in LB medium at 37 °C until the A600 reached 0.6 and then induced with 0.3 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside at 16 °C for ∼16–18 h. After centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 min, the E. coli cells were resuspended in T50N500I5 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 500 mm NaCl, and 5 mm imidazole) supplemented with 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml antipain. To create the tripartite yElp4–6 complex, the cells expressing yElp4 and those co-expressing yElp5 and yElp6 were mixed at a ratio of 1:1. The mixed cells were lysed via sonication. After the lysates had been centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with T50N500I5 buffer. The HisTrap HP column was then washed with 10 column volumes of T50N500I5 buffer. The Trx-His6-tagged tripartite complex was eluted with an imidazole gradient of 5–1000 mm in T50N500I5 buffer. The eluted complex was then loaded on a HighLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with T50N50E1D1 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT) at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. Each fraction of the column elute was 5 ml. The protein was identified by SDS-PAGE, and the corresponding fractions were pooled and digested with 3C protease to cleave the Trx-His6 tag. Then, the target complex proteins were further purified using a MonoQ column (GE Healthcare) eluted with an NaCl gradient of 50–500 mm in T50N50E1D1 buffer. The final target complex was loaded onto a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with T50N50E1D1 buffer. The protein was identified by SDS-PAGE, and the corresponding fractions were pooled and concentrated to 14 mg/ml for crystallization trials. The yElp4–6 mutant proteins were produced in the same way as the wild type. The SeMet derivative protein was produced following the same protocol used for the wild-type protein, except that methionine auxotroph E. coli B834 (DE3) cells and LeMaster medium were used to express the recombinant protein.

Crystallization and Data Collection

The crystals of either the wild-type or the SeMet-substituted yElp4–6 subcomplex were grown at 20 °C at a protein concentration of 14 mg/ml using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. The protein was equilibrated against a reservoir solution of 100 mm bis-tris propane (pH 7.0) and 800 mm dl-malic acid (pH 7.0) for 3 days. Both crystals were frozen in a cryoprotectant that consisted of the reservoir solution supplemented with 3.5 m sodium formate.

The crystals of the wild-type yElp4–6 subcomplex diffracted to 2.6 Å with a space group of I23 and unit cell dimensions of a = b = c = 186.5 Å. The SeMet-substituted crystals diffracted to 2.8 Å with the same space group and unit cell dimensions of a = b = c = 186.7 Å. Both data sets were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 software package (39).

Structure Determination and Refinement

The HKL2MAP program (40) identified 13 selenium sites in one asymmetric unit, and the initial single anomalous dispersion phases were calculated using PHENIX software (41). The residues were first built automatically by the PHENIX program package (41) and then were manually built using the COOT program (42) based on 2Fobs − Fcalc and Fobs − Fcalc difference Fourier maps. The structural model was refined using the CNS program (43) and the PHENIX program (41). The final structure had an Rcryst value of 17.4% and an Rfree value of 22.4%. Detailed data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in supplemental Table S1.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity (SV)4 and sedimentation equilibrium (SE) experiments were performed using a Beckman/Coulter XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge using double-sector or six-channel centerpieces and sapphirine windows. The SV experiments were conducted at 40,000 rpm and 12 °C using absorbance detection and double-sector cells loaded with ∼17.6 and 8.8 μm yElp4–6 subcomplex, 17.6 μm mutant yElp4–6, 13.1 μm binary yElp5–6 complex, and 26.4 μm yElp4. For the SE experiments, data were collected at 4 °C and 6,000, 9,000, and 11,500 rpm with ∼8.8, 5.3, and 3.5 μm concentrations of the yElp4–6 subcomplex. The buffer composition (density and viscosity) and the protein partial specific volume (V-bar) were obtained using the SEDNTERP program (available through the Boston Biomedical Research Institute). The SV and SE data were analyzed using the SEDFIT and SEDPHAT programs (44, 45), respectively.

Co-immunoprecipitation

To test dimer formation of the full-length Elp4–6 subcomplex, HEK293T cells were transfected with various combinations of plasmids as indicated. Transfected HEK293T cells were lysed with ice-cold cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 3% glycerol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml antipain) and cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then incubated with agarose conjugated anti-GFP (clone RQ2, Medical & Biological Laboratories) for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed with cell lysis buffer and eluted with SDS sample buffer. The prepared samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and then analyzed using Western blot.

GST Pulldown Assays

H3(1–28)-GST was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus cells and purified using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare) and a Superdex 200 size-exclusion column. Transfected HEK293T cells were lysed with ice-cold cell lysis buffer and cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Soluble fractions were incubated with GST fusion proteins at 4 °C for 2 h. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) were then added for further incubation at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed with lysis buffer and boiled in SDS sample buffer. The prepared samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and then analyzed using Western blot.

RESULTS

Interactions within Elp4–6 Subcomplex

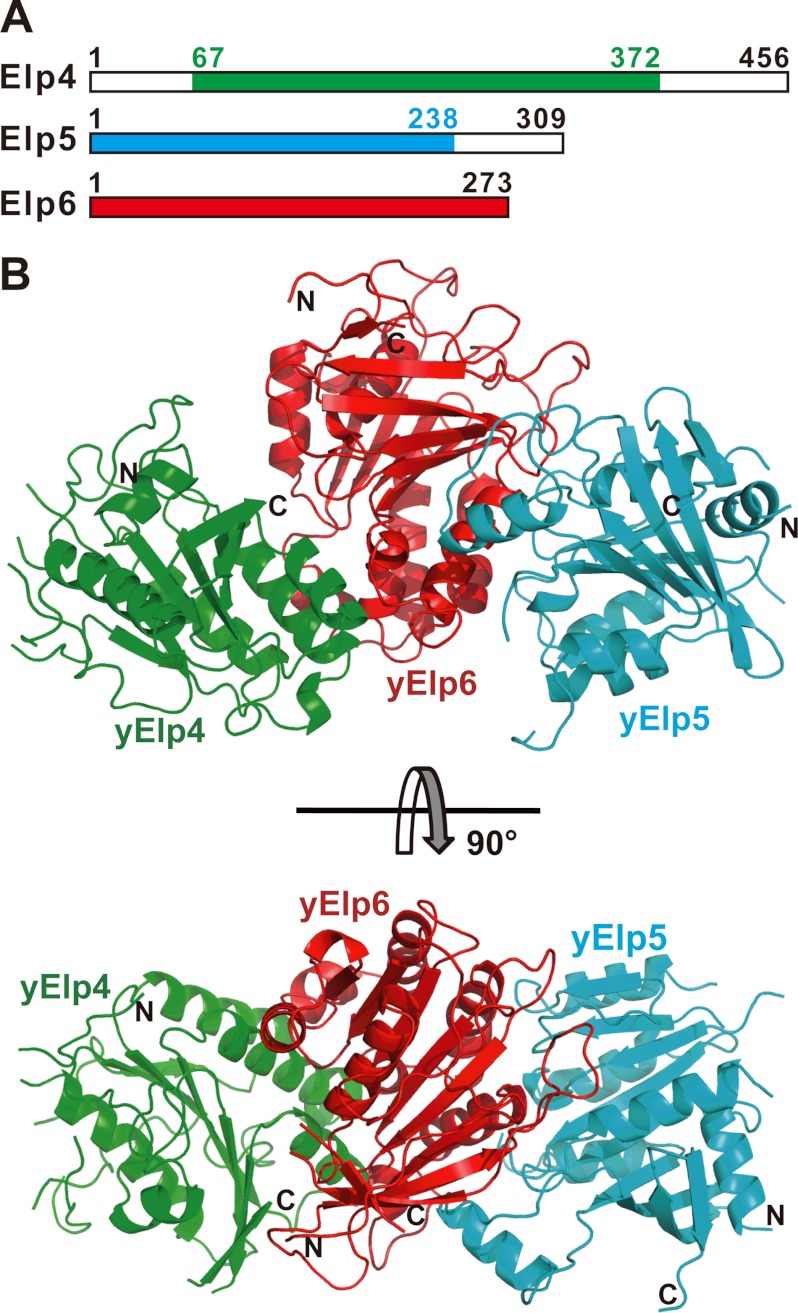

Prior studies have shown that Elp4, Elp5, and Elp6 form a stable tripartite complex that is indispensable for functioning of the holo-Elongator complex (9–11). To reconstitute the yeast Elongator subcomplex Elp4–6 in vitro, several constructs of yeast Elp5 were designed and tested for protein co-expression with yeast Elp6 and purity (supplemental Fig. S1A). A construct containing residues 1–238 of Elp5 (hereafter referred to as yElp5) and full-length Elp6 (residues 1–273, hereafter referred to as yElp6) were co-expressed at a high level, and the purified proteins exhibited excellent stability in solution (supplemental Fig. S1A). Several constructs of yeast Elp4 also were designed and tested for protein expression and purity (supplemental Fig. S1B). The purified proteins of the tripartite complex that contained an Elp4 fragment (residues 67–372, hereafter referred to as yElp4), yElp5, and yElp6 exhibited the best stability (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S1B). The results from the size-exclusion and SDS-PAGE experiments revealed that the tripartite yElp4–6 forms a stable 1:1:1 stoichiometric complex (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D).

FIGURE 1.

Crystal structure of the yeast Elp4–6 subcomplex. A, schematic representation of Elp4, Elp5, and Elp6. The gene fragments of the tripartite complex used for structural determination in this study are as follows: yElp4 (residues 67–372) colored in green, yElp5 (residues 1–238) in cyan, and yElp6 (residues 1–273) in red. B, a schematic representation of the structure of the yElp4–6 subcomplex. yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 are colored as in A. Shown are the side view (upper panel) and top view (lower panel). The N and C termini of these three proteins are labeled.

Overall Structure of yElp4–6 Subcomplex

To understand the molecular mechanism underlying assembly of the Elongator subcomplex yElp4–6, we solved the crystal structure of the yElp4–6 subcomplex using single anomalous dispersion at a resolution of 2.6 Å (supplemental Table S1). The crystal belongs to the space group I23 and contains one yElp4–6 subcomplex per asymmetric unit. yElp4 is well resolved from Gly-67 to Arg-367 except for residues 137–144, 169–234, and 357–360. yElp5 is well resolved from residues Asn-7 to Thr-234 except for residues 142–148. Residues 2–272 of yElp6 are all defined clearly in the electron density map. The overall structure shows that yElp6 is located in the center of the complex and bridges yElp4 and yElp5. yElp4 and yElp5 have no direct interaction in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this observation, prior studies have shown that Elp6 interacts with both Elp4 and Elp5 but that Elp4 and Elp5 do not bind to each other (12, 19, 36, 37).

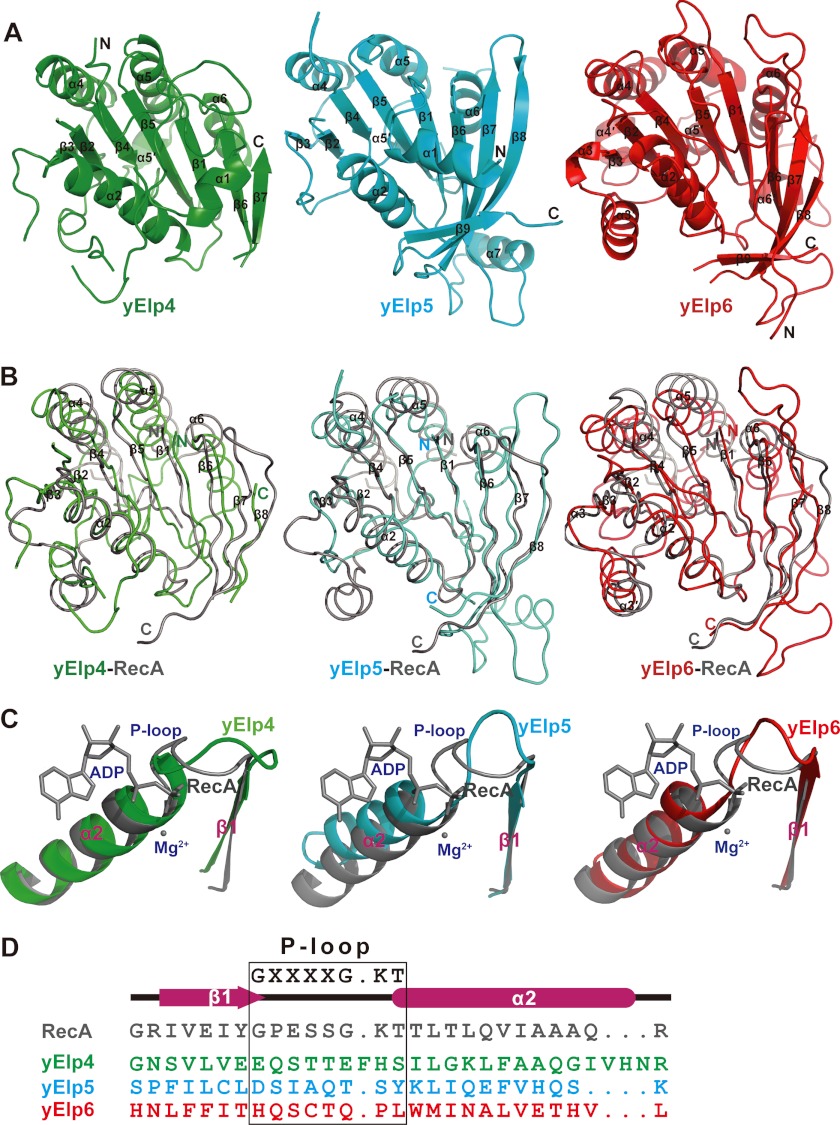

yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 have similar compact globular folds with a core root mean square deviation value of 2.6–2.7 Å. The overall structures of yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 contain a central, parallel β-sheet flanked by several helices (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 all adopt similar RecA-ATPase-like folds. A, a cartoon representation of each subunit of the yElp4–6 complex. yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 are shown in green, cyan, and red, respectively. B, the superimposed structures of yElp4 (green), yElp5 (cyan), and yElp6 (red) with RecA (gray, Protein Data Bank code 2REB). The conserved strands and helices are marked. C, detailed structural comparison of the P-loop region between RecA (gray, ADP+Mg2+-binding form, Protein Data Bank code 1XMV) and yElp4 (green), yElp5 (cyan), or yElp6 (red). D, structure-based sequence alignment of the potential P-loop region of yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 with that of E. coli RecA. The P-loop region is marked with a black box. The consensus sequence GXXXXGKT (X is any residue) is the Walker motif A.

yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 All Adopt Similar RecA-ATPase-like Folds

The common structural elements among yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 are β1–7, α2, and α4–6 and are similar to those elements within proteins with helicase-like ATPase folds, such as RecA (46). In comparison with the structure of the RecA central ATPase domain of E. coli, yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 have root mean square deviation values of 2.6 Å for 158 Cα atoms (Fig. 2B, left panel), 2.6 Å for 150 Cα atoms (Fig. 2B, middle panel), and 2.7 Å for 167 Cα atoms (Fig. 2B, right panel), respectively. RecA is a typical P-loop ATPase that uses the well known Walker motif A consensus sequence, which connects strand β1 and helix α2 for ATP binding ((G/A)XXXXGK(T/S)), where X is any residue) (46). Although both the β1 strand and the α2 helix are highly conserved among yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6, there is a noticeable difference in the region of the P-loop (Fig. 2C). Comparison of the sequence of the potential P-loop regions of yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 with that of RecA revealed no consensus residues in the Walker motif A (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these structural and sequence analyses indicated that yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 all adopt RecA-ATPase-like folds lacking the key sequence signature of ATPases.

Interface in yElp4–6 Subcomplex

The crystal structure revealed that yElp4 and yElp5 directly interact with both sides of yElp6 to form a stable tripartite complex (Fig. 1B). A buried surface area of 956 Å2 for the yElp4-yElp6 interface and 1,424 Å2 for the yElp5-yElp6 interface was calculated using AREAIMOL (47). The residues of helices α5 and α6 of yElp4 support the interaction with yElp6. Specifically, Asn-346 of yElp4 forms several hydrogen bonds with Gln-150 and Asn-186 of yElp6 (supplemental Fig. S2A). Glu-303 and Lys-320 of yElp4 also form hydrogen bonds with Ser-159 and Asp-111 of yElp6, respectively. Other residues forming hydrophobic interactions at the interface include Ile-308, Lys-319, Pro-338, Pro-339, Val-342, and Met-347 of yElp4 and Glu-85, Leu-153, Leu-157, Ile-192, and Tyr-195 of yElp6. Detailed interactions at the yElp4 and yElp6 interface are shown in supplemental Fig. S2A.

An extensive network of 17 hydrogen bonds is found at the interface of yElp5 and yElp6, involving residues Tyr-36, Ser-59, Asp-74, Tyr-111, Lys-140, Arg-195, Asn-198, and Asn-199 from yElp5 and Asn-167, Arg-176, Gln-205, Asn-206, Asn-210, Arg-240, Pro-244, and Glu-258 from yElp6. Tyr-36 of yElp5 also forms a stacking interaction with Pro-244 of yElp6. In addition, Ile-31 and Phe-191 from yElp5 stack against the hydrophobic cavity formed by Phe-33, Phe-190, Phe-212, and Ile-213 of yElp6. Detailed interactions at the interface of yElp5 and yElp6 are shown in supplemental Fig. S2B.

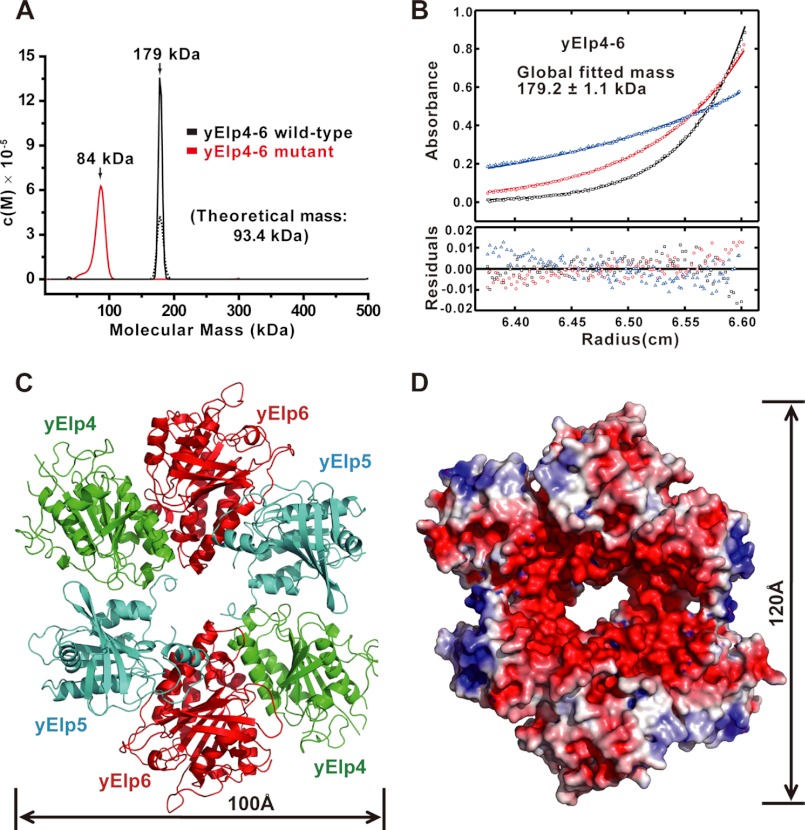

yElp4–6 Subcomplex Is Homodimer in Solution and Forms Ring-shaped Structure

The subcomplex proteins containing the RecA-ATPase fold belong to the RecA superfamily and adopt hexameric rings (48, 49) Therefore, the yElp4–6 subcomplex may also form a homodimer. To test this hypothesis, the yElp4–6 subcomplex was purified to homogeneity and analyzed using analytical ultracentrifugation. The SV analysis indicated that the yElp4–6 subcomplex forms a stable homodimer of heterotrimers (Fig. 3A, black lines). The SE analysis further confirmed that the tripartite yElp4–6 complex assembles into a homodimer of heterotrimers with a molecular mass of ∼179.2 kDa (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S3). Thus, we concluded that the Elongator subcomplex yElp4–6 forms a homodimer of heterotrimers containing six subunits in solution.

FIGURE 3.

The hexamer of the yElp4–6 subcomplex. A, SV analysis of the yElp4–6 subcomplex proteins. The wild-type tripartite yElp4–6 complex is shown with black lines, and the tripartite yElp4–6 mutant complex containing the two point mutations at H293A and F302A in yElp4 is shown with the red line. Solid and dotted lines represent protein concentrations of ∼17.6 and 8.8 μm, respectively. B, a representative SE analysis of the tripartite yElp4–6 complex derived from a global fit revealed a molecular mass of ∼179.2 ± 1.1 kDa, indicating that the wild-type yElp4–6 subcomplex assembles into a hexamer (dimer of heterotrimers). C, ribbon representation of the hexamer of the yElp4–6 subcomplex. yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 are shown in green, cyan, and red, respectively. D, the solvent-accessible electrostatic surface representation of the hexamer of the yElp4–6 subcomplex. The surfaces are colored according to the electrostatic potential, ranging from deep blue (positive charge, +5 kT/e) to red (negative charge, −5 kT/e). The electrostatic potentials were calculated using ABPS tools (51) with its default settings.

With a crystallographic 2-fold axis, the overall shape of the yElp4–6 hexamer resembles a ring-shaped structure with dimensions of 100 × 120 Å (Fig. 3, C and D). The yElp4–6 hexamer displays a negatively charged surface on one side and a hole in the center with dimensions of 13 × 24 Å (Fig. 3D). Various residues of yElp4 and yElp5 contribute to the two identical interfaces of the hexamer (dimer of heterotrimers). Importantly, the phenyl group of Phe-302 and the imidazolyl group of His-293 of yElp4 form stacking interactions with the side chain atoms CD1 and CE1 of Tyr-154 and CE2 and CZ of Phe-163 of yElp5, respectively (supplemental Fig. S4). The side chain of Phe-302 of yElp4 also forms hydrophobic interactions with the side chain of Pro-155 of yElp5. In addition, hydrogen bonds primarily from the main chain carbonyl and the amino atoms of residues Thr-116, Glu-117, and Ser-304 (yElp4) and Ser-212, Gly-213, and Arg-214 (yElp5) contribute to the interface of yElp4 and yElp5. Detailed interactions of one of the two interfaces of yElp4 and yElp5 are shown in supplemental Fig. S4. Next, we directly tested the role of the interactions between yElp4 and yElp5 observed in the hexamer yElp4–6 structure. Mutation of both residues His-293 and Phe-302 of yElp4 to alanines did not disrupt yElp4 from binding to yElp5 and yElp6 to form a tripartite complex. For the remainder of the discussion, this tripartite complex containing the two mutations (H293A and F302A in yElp4) is referred to as the yElp4–6 mutant. Consistent with the structure-based prediction, mutating both His-293 and Phe-302 to alanines disrupted assembly of the dimer of heterotrimers for the yElp4–6 mutant. The purified yElp4–6 mutant forms a heterotrimer with a molecular mass of ∼84 kDa according to SV analysis (Fig. 3A, red line). During the revision of this manuscript, a study by Glatt et al. (50) also showed that the yeast Elp4–6 subcomplex forms a heterohexameric ring-like structure (supplemental Fig. S5). Taken together, we conclude that the Elongator subcomplex yElp4–6 forms a hexameric ring-shaped structure in solution.

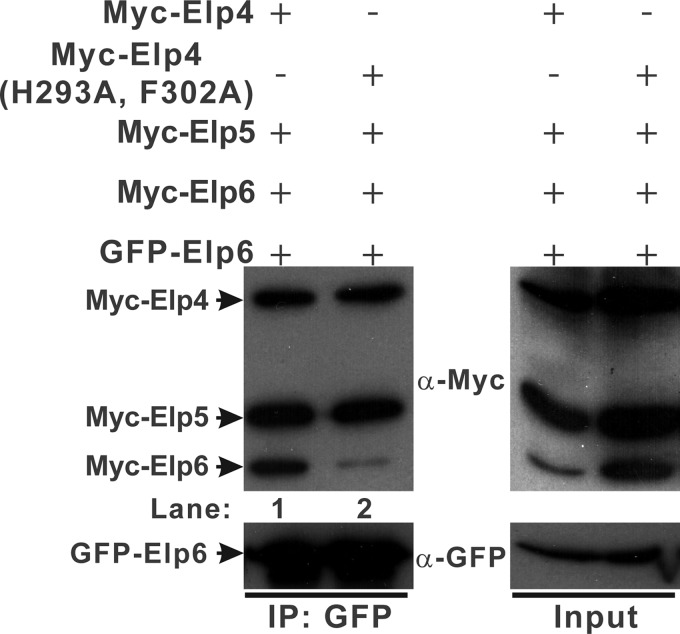

Elp4–6 Subcomplex Dimerizes in Vivo

To test for homodimer formation of the full-length Elp4–6 subcomplex in vivo, we used a co-precipitation strategy using two different tags on Elp6 and tested their interaction in the context of either the wild-type or the mutant Elp4–6 complex. As expected, wild-type Myc-Elp4, mutant Myc-Elp4 (H293A, F302A) and Myc-Elp5 specifically co-precipitated with GFP-Elp6 (Fig. 4A, left panel). Notably, GFP-Elp6 co-precipitated with Myc-Elp6 in the wild-type Elp4–6 complex (lane 1 in Fig. 4A), whereas negligible amounts of Myc-Elp6 co-precipitated in the mutant Elp4–6 complex (lane 2 in Fig. 4A), indicating dimerization of the Elp4–6 subcomplex in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

The Elp4–6 subcomplex dimerizes in vivo. Extracts were prepared from HEK293T cells transfected with various combinations of plasmids as indicated, immunoprecipitated with agarose conjugated anti-GFP and subsequently immunoblotted with α-Myc (upper panels) or α-GFP (lower panels) as indicated. The left panels show the immunoprecipitation (IP) results (lane 1, wild-type Elp4–6 complex; lane 2, mutant Elp4–6 complex), and the right panels represent 2% of the input material for each immunoprecipitation. The mobilities of Myc-Elp4, Myc-Elp4 (H293A, F302A), Myc-Elp5, Myc-Elp6, and GFP-Elp6 are indicated in the left margin.

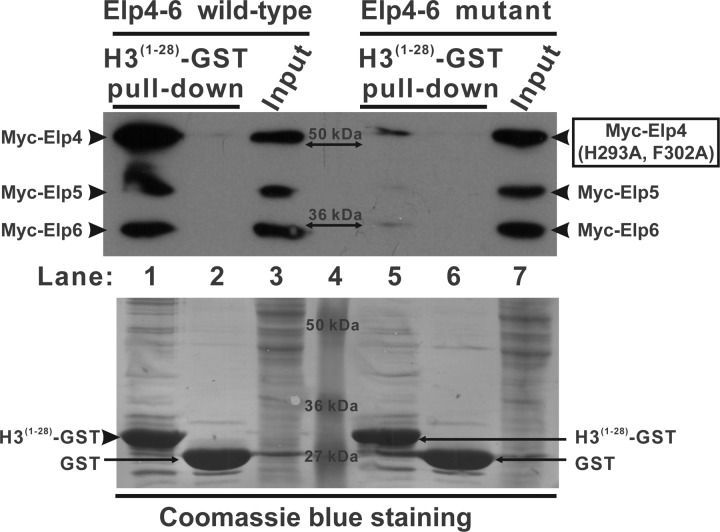

Elp4–6 Subcomplex Specifically Recognizes Histone H3

Based on the formation of the ring-shaped yElp4–6 hexamer with a negatively charged surface on one side and a hole in the center (Fig. 3D), together with the observation that the holo-Elongator complex has been shown to acetylate histone H3 (17), we speculated that the Elp4–6 subcomplex may bind to histone H3. To test this hypothesis, the first 28 amino acids of the N-terminal yeast histone H3 were fused to the N terminus of GST (H3(1–28)-GST). In a GST pulldown assay, H3(1–28)-GST bound to the tripartite Elp4–6 complex homodimer (lane 1 in Fig. 5) with a much higher affinity than to the mutant Elp4–6 complex (incapable of homodimer formation) in the same experiment (lane 5 in Fig. 5), indicating that the ring-shaped assembly of the Elp4–6 subcomplex may play an important role in recognizing histone H3 during holo-Elongator-mediated histone acetylation.

FIGURE 5.

Interaction of the Elp4–6 subcomplex with histone H3. H3(1–28)-GST fusion proteins (lanes 1 and 5) or GST alone (lanes 2 and 6) were incubated with the extracts of HEK293T cells transfected with the wild-type or the mutant Elp4–6 complex. Lanes 3 and 7 represent 4% of the input material for the corresponding pulldown. The PVDF membrane was immunoblotted with α-Myc (upper panel) and subsequently stained with Coomassie Blue (lower panel). The mobilities of Myc-Elp4, Myc-Elp4 (H293A, F302A), Myc-Elp5, Myc-Elp6, and the GST proteins are indicated in the margins. The molecular mass of each protein marker is indicated in lane 4.

DISCUSSION

The crystal structure of the yElp4–6 subcomplex solved in this work provides structural information regarding the molecular mechanism of Elongator subcomplex Elp4–6 assembly. The structures of yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 resemble typical RecA-ATPase domains, even though no sequence homology is shared among them. In addition, the detailed structural and sequence analyses revealed that yElp4, yElp5, and yElp6 all adopt RecA-ATPase-like folds lacking the key sequence signature of ATPases. Furthermore, the structure-based mutagenesis and biochemical analyses indicated that the yElp4–6 complex may form a hexameric ring-shaped structure under physiological conditions that is important for histone H3 binding.

During revision of this manuscript, Glatt et al. (50) reported a similar crystal structure of the yeast Elp4–6 subcomplex (supplemental Fig. S5). The overall fold of Glatt's structure is highly similar to ours with an root mean square deviation value of 0.8 Å for 682 Cα atoms. Except for structural differences of some loops caused by different crystallization conditions, our structure of yElp4 lacks two C-terminal strands β8 and β9 present in Glatt's structure of Elp4 due to the different constructs used for crystallization. The yeast constructs Elp467–372, Elp51–238, and Elp61–273 were used in this study, and the yeast constructs Elp466–426, Elp51–270, and Elp61–273 were used in Glatt's study. Both structures show that Elp4, Elp5, and Elp6 adopt RecA-ATPase-like folds and assemble into a hexameric ring-shaped structure.

The ring-shaped structure of the yElp4–6 hexamer (Fig. 1B) indicates that each subunit is required for the dimer of heterotrimers to form, which is consistent with the observation that knock-outs of any of the ELP4, ELP5, and ELP6 genes cause similar phenotypes in yeast (9–11). It should also be noted that only yElp4 and the yElp5–6 binary complex were not able to form higher-order oligomers (supplemental Fig. S6). Our results also showed that the ring-shaped structure of the Elp4–6 subcomplex is important for histone H3 binding (Fig. 5). However, we could not identify a direct interaction of the Elp4–6 subcomplex with the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (supplemental Fig. S7) by either isothermal titration calorimetry or co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), although previous studies have shown the association of the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II with the holo-Elongator complex (8, 32). It is possible that we have not yet caught the correct phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II or that other Elongator subunits Elp1, Elp2, and Elp3 contribute to the interaction of the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II with the holo-Elongator complex. Glatt et al. showed a direct and specific interaction of the Elp4–6 subcomplex with nucleic acids of tRNA in a manner regulated by ATP, but not with single-stranded DNA or single-stranded oligonucleotide (U) RNA (50). Thus, we conclude that the Elp4–6 subcomplex may play vital roles in substrate recognition, at least during holo-Elongator complex-mediated histone H3 acetylation and tRNA modification. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the molecular mechanism of substrate recognition by the Elp4–6 subcomplex.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the staff at beamline BL17U1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

This work was supported by the 973 Program (Grants 2009CB825504 and 2012CB917201), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31100527, 31140029, and 31170684), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grants 65011621 and 65020241).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S7.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4EJS) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- SV

- sedimentation velocity

- SE

- sedimentation equilibrium.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shilatifard A., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2003) The RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 693–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Selth L. A., Sigurdsson S., Svejstrup J. Q. (2010) Transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 271–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li B., Carey M., Workman J. L. (2007) The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128, 707–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clapier C. R., Cairns B. R. (2009) The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 273–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bannister A. J., Kouzarides T. (2011) Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 21, 381–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown C. E., Lechner T., Howe L., Workman J. L. (2000) The many HATs of transcription coactivators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pokholok D. K., Harbison C. T., Levine S., Cole M., Hannett N. M., Lee T. I., Bell G. W., Walker K., Rolfe P. A., Herbolsheimer E., Zeitlinger J., Lewitter F., Gifford D. K., Young R. A. (2005) Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell 122, 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Otero G., Fellows J., Li Y., de Bizemont T., Dirac A. M., Gustafsson C. M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (1999) Elongator, a multisubunit component of a novel RNA polymerase II holoenzyme for transcriptional elongation. Mol. Cell 3, 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winkler G. S., Petrakis T. G., Ethelberg S., Tokunaga M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (2001) RNA polymerase II elongator holoenzyme is composed of two discrete subcomplexes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32743–32749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y., Takagi Y., Jiang Y., Tokunaga M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Kornberg R. D. (2001) A multiprotein complex that interacts with RNA polymerase II elongator. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29628–29631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krogan N. J., Greenblatt J. F. (2001) Characterization of a six-subunit holo-elongator complex required for the regulated expression of a group of genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 8203–8212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frohloff F., Jablonowski D., Fichtner L., Schaffrath R. (2003) Subunit communications crucial for the functional integrity of the yeast RNA polymerase II elongator (γ-toxin target (TOT)) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 956–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petrakis T. G., Wittschieben B. Ø., Svejstrup J. Q. (2004) Molecular architecture, structure-function relationship, and importance of the Elp3 subunit for the RNA binding of holo-elongator. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32087–32092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slaugenhaupt S. A., Blumenfeld A., Gill S. P., Leyne M., Mull J., Cuajungco M. P., Liebert C. B., Chadwick B., Idelson M., Reznik L., Robbins C., Makalowska I., Brownstein M., Krappmann D., Scheidereit C., Maayan C., Axelrod F. B., Gusella J. F. (2001) Tissue-specific expression of a splicing mutation in the IKBKAP gene causes familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 598–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson S. L., Coli R., Daly I. W., Kichula E. A., Rork M. J., Volpi S. A., Ekstein J., Rubin B. Y. (2001) Familial dysautonomia Is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 753–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wittschieben B. O., Fellows J., Du W., Stillman D. J., Svejstrup J. Q. (2000) Overlapping roles for the histone acetyltransferase activities of SAGA and elongator in vivo. EMBO J. 19, 3060–3068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winkler G. S., Kristjuhan A., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (2002) Elongator is a histone H3 and H4 acetyltransferase important for normal histone acetylation levels in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3517–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Close P., Hawkes N., Cornez I., Creppe C., Lambert C. A., Rogister B., Siebenlist U., Merville M. P., Slaugenhaupt S. A., Bours V., Svejstrup J. Q., Chariot A. (2006) Transcription impairment and cell migration defects in elongator-depleted cells: Implication for familial dysautonomia. Mol. Cell 22, 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nelissen H., De Groeve S., Fleury D., Neyt P., Bruno L., Bitonti M. B., Vandenbussche F., Van der Straeten D., Yamaguchi T., Tsukaya H., Witters E., De Jaeger G., Houben A., Van Lijsebettens M. (2010) Plant elongator regulates auxin-related genes during RNA polymerase II transcription elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1678–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Creppe C., Malinouskaya L., Volvert M. L., Gillard M., Close P., Malaise O., Laguesse S., Cornez I., Rahmouni S., Ormenese S., Belachew S., Malgrange B., Chapelle J. P., Siebenlist U., Moonen G., Chariot A., Nguyen L. (2009) Elongator controls the migration and differentiation of cortical neurons through acetylation of α-tubulin. Cell 136, 551–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solinger J. A., Paolinelli R., Klöss H., Scorza F. B., Marchesi S., Sauder U., Mitsushima D., Capuani F., Stürzenbaum S. R., Cassata G. (2010) The Caenorhabditis elegans elongator complex regulates neuronal alpha-tubulin acetylation. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paraskevopoulou C., Fairhurst S. A., Lowe D. J., Brick P., Onesti S. (2006) The elongator subunit Elp3 contains a Fe4S4 cluster and binds S-adenosylmethionine. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 795–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okada Y., Yamagata K., Hong K., Wakayama T., Zhang Y. (2010) A role for the elongator complex in zygotic paternal genome demethylation. Nature 463, 554–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simpson C. L., Lemmens R., Miskiewicz K., Broom W. J., Hansen V. K., van Vught P. W., Landers J. E., Sapp P., Van Den Bosch L., Knight J., Neale B. M., Turner M. R., Veldink J. H., Ophoff R. A., Tripathi V. B., Beleza A., Shah M. N., Proitsi P., Van Hoecke A., Carmeliet P., Horvitz H. R., Leigh P. N., Shaw C. E., van den Berg L. H., Sham P. C., Powell J. F., Verstreken P., Brown R. H., Jr., Robberecht W., Al-Chalabi A. (2009) Variants of the Elongator protein 3 (ELP3) gene are associated with motor neuron degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ponting C. P. (2002) Novel domains and orthologues of eukaryotic transcription elongation factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3643–3652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strug L. J., Clarke T., Chiang T., Chien M., Baskurt Z., Li W., Dorfman R., Bali B., Wirrell E., Kugler S. L., Mandelbaum D. E., Wolf S. M., McGoldrick P., Hardison H., Novotny E. J., Ju J., Greenberg D. A., Russo J. J., Pal D. K. (2009) Centrotemporal sharp wave EEG trait in rolandic epilepsy maps to elongator protein complex 4 (ELP4). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17, 1171–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kleinjan D. A., Seawright A., Elgar G., van Heyningen V. (2002) Characterization of a novel gene adjacent to PAX6, revealing synteny conservation with functional significance. Mamm. Genome 13, 102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crolla J. A., van Heyningen V. (2002) Frequent chromosome aberrations revealed by molecular cytogenetic studies in patients with aniridia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1138–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X., Zhang Q., Tong Y., Dai H., Zhao X., Bai F., Xu L., Li Y. (2011) Large novel deletions detected in Chinese families with aniridia: Correlation between genotype and phenotype. Mol. Vis. 17, 548–557 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wittschieben B. O., Otero G., de Bizemont T., Fellows J., Erdjument-Bromage H., Ohba R., Li Y., Allis C. D., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (1999) A novel histone acetyltransferase is an integral subunit of elongating RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol. Cell 4, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hawkes N. A., Otero G., Winkler G. S., Marshall N., Dahmus M. E., Krappmann D., Scheidereit C., Thomas C. L., Schiavo G., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. (2002) Purification and characterization of the human elongator complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3047–3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim J. H., Lane W. S., Reinberg D. (2002) Human elongator facilitates RNA polymerase II transcription through chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1241–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang B., Johansson M. J., Byström A. S. (2005) An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the elongator complex. RNA 11, 424–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Esberg A., Huang B., Johansson M. J., Byström A. S. (2006) Elevated levels of two tRNA species bypass the requirement for elongator complex in transcription and exocytosis. Mol. Cell 24, 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rahl P. B., Chen C. Z., Collins R. N. (2005) Elp1p, the yeast homolog of the FD disease syndrome protein, negatively regulates exocytosis independently of transcriptional elongation. Mol. Cell 17, 841–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fichtner L., Frohloff F., Jablonowski D., Stark M. J., Schaffrath R. (2002) Protein interactions within Saccharomyces cerevisiae Elongator, a complex essential for Kluyveromyces lactis zymocicity. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Q., Fazly A. M., Zhou H., Huang S., Zhang Z., Stillman B. (2009) The elongator complex interacts with PCNA and modulates transcriptional silencing and sensitivity to DNA damage agents. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker J., Kwon S. Y., Badenhorst P., East P., McNeill H., Svejstrup J. Q. (2011) Role of elongator subunit Elp3 in Drosophila melanogaster larval development and immunity. Genetics 187, 1067–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pape T., Schneider T. R. (2004) HKL2MAP: A graphical user interface for phasing with SHELX programs. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 37, 843–844 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zwart P. H., Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., McKee E., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Storoni L. C., Terwilliger T. C., Adams P. D. (2008) Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 426, 419–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schuck P. (2000) Size distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 78, 1606–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schuck P. (2003) On the analysis of protein self-association by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Anal. Biochem. 320, 104–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Story R. M., Weber I. T., Steitz T. A. (1992) The structure of the Escherichia coli recA protein monomer and polymer. Nature 355, 318–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee B., Richards F. M. (1971) Interpretation of protein structures: Estimation of static accessibility. J. Mol. Biol. 55, 379–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leipe D. D., Aravind L., Grishin N. V., Koonin E. V. (2000) The bacterial replicative helicase dnaB evolved from a RecA duplication. Genome Res. 10, 5–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vale R. D. (2000) AAA Proteins. Lords of the ring. J. Cell Biol. 150, F13–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glatt S., Létoquart J., Faux C., Taylor N. M., Séraphin B., Müller C. W. (2012) The elongator subcomplex Elp456 is a hexameric RecA-like ATPase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 314–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J., McCammon J. A. (2001) Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]