Abstract

Wilson’s disease is a rare genetic disorder of copper metabolism. The difference in copper tissue accumulation is responsible for the various clinical manifestations of this disorder. If left untreated, Wilson’s disease progresses to hepatic failure, severe neurological disability, and even death. Due to the complex clinical picture of Wilson’s disease, its diagnosis relies on a high index of suspicion. In our paper, we present endocrine symptoms suggesting the presence of insulinoma and hyperprolactinemia as the initial clinical manifestation of Wilson’s disease in a young female. Zinc acetate treatment resulted in the disappearance of hypoglycemia, galactorrhea, and menstrual abnormalities.

Keywords: Wilson’s disease, insulinoma, prolactinoma, zinc acetate

Introduction

Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration) is a rare autosomal recessive inherited disorder of copper metabolism. The mutations in the ATP7B gene lead to impaired biliary excretion of copper, the consequence of which is abnormal accumulation of copper in the liver, basal ganglia, kidneys, and cornea [1-3]. This results in severe and potentially life threatening injury to vital organs, especially the liver and nervous system. Unless specific treatment (with penicillamine, trientine, or zinc) is given, the disease leads almost inevitably to death. A characteristic feature of hepatolenticular degeneration is its variable manifestation, partially dependent on the age of the disease onset that makes it legitimate to consider Wilson’s disease in the differential diagnosis of various pathologies [1,2]. Retrospective data show that its earliest manifestation is in 42 percent of cases of liver damage, in 34 percent of neurological disorders, in 12 percent of hematologic disorders, in 10 percent of psychiatric symptoms, while in 1 percent of kidney dysfunction [3].

Here we report a case of a young woman with Wilson’s disease who initially presented with symptoms suggestive of excessive prolactin and insulin release. We present diagnostic and treatment dilemmas associated with Wilson’s disease in this case patient.

Case Presentation

A 24-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital to establish the causes of galactorrhea, menstrual abnormalities, and hypoglycemia. Nipple discharge in response to breast manipulation appeared for the first time at the age of 19. Approximately at the same time, the patient began to complain of menstrual abnormalities, first beginning with oligomenorrhea, which advanced to amenorrhea. High doses (up to 15 mg/day) of bromocriptine treatment prescribed by a gynecologist resulted in only partial improvement (galactorrhea reduction, oligomenorrhea instead of amenorrhea). Taking into consideration moderate effectiveness of the therapy and poor drug tolerance (nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension), the bromocriptine treatment was replaced with oral contraceptives. After discontinuation of a 14-month treatment with contraceptives, eumenorrhea recurred with the reappearance of amenorrhea. Looking further back in the patient history revealed that at the age of 23, the patient started to experience symptoms of hypoglycemia (sweating, pallor, hand tremor, and palpitation attacks), confirmed several times by ambulatory glucose measurement. These symptoms occurred predominantly in the morning, late afternoon, and during physical exertion. The symptoms gradually increased in frequency and intensity but subsided after candies or sweet drink consumption. Additionally, vision impairment, convulsions, and transient motor defects appeared on several occasions. Because of clinical features suggesting hyperprolactinemia, we assayed plasma prolactin levels repeatedly, each time obtaining results within normal limits (Table 1). On further examination, the characteristics of the breast discharge were neither inflammatory nor neoplastic. However, the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary gland revealed a small, hypointense area (3.5 mm in diameter) that could be a microadenoma. Pituitary tests showed no hormonal activity of this lesion (Table 1). Transvaginal ultrasonography (USG) examination revealed features of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) not accompanied by any abnormalities in gonadal and adrenal androgen secretion.

Table 1. Baseline hormonal profile of the patient.

| Hormone | Unit | Concentration | Normal limits |

| Prolactin | µg/L | 12.7* | 5.0-25.0 |

| GH in the oral glucose tolerance test | µg/L | 0.2 | < 1.0 |

| IGF-I | µg/L | 137.0 | 72.0-335.0 |

| ACTH | ng/L | 48.2 | 20.0-60.0 |

| TSH | mU/L | 1.95 | 0.4-4.5 |

| FSH** | U/L | 6.82 | 3.4-12.5 |

| LH** | U/L | 6.84 | 2.3-12.7 |

| Intact parathormone | ng/L | 42.2 | 10.0-70.0 |

| Free thyroxine | pmol/L | 16.5 | 12.0-22.0 |

| Cortisol | µg/dL | ||

| in the overnight dexamethasone test | 1.2 | <1.8 | |

| in the 250-µg cosyntropin test | 27.2 | >19.6 | |

| Urine free cortisol | µg/day | 62.2* | 20.0-90.0 |

| DHEA-sulphate | µg/dL | 281.5 | 80.0-450.0 |

| 17β-oestradiol** | ng/L | 60.5 | 30.0-100.0 |

| Testosterone | µg/L | 0.35 | 0.15-0.8 |

| Androstendione | µg/L | 1.7 | 0.6-3.2 |

| 17-hydroxyprogesterone** | µg/L | 0.45 | 0.2-1.0 |

| Free androgen index | % | 4.2 | <5.0 |

| Insulin | mU/L | ||

| Baseline | 18.6 | 6.0-25.0 | |

| after the fasting test | 0.0 | <3.0 | |

| C-peptide | µg/L | ||

| Baseline | 1.5 | 0.6-2.0 | |

| after the fasting test | 0.0 | <0.6 | |

| Proinsulin after the fasting test | pmol/L | 0.1 | <5.0 |

| β-hydroxybutyrate after the fasting test | mmol/L | 3.5 | >2.7 |

*Mean value of several measurements

**Early follicular phase

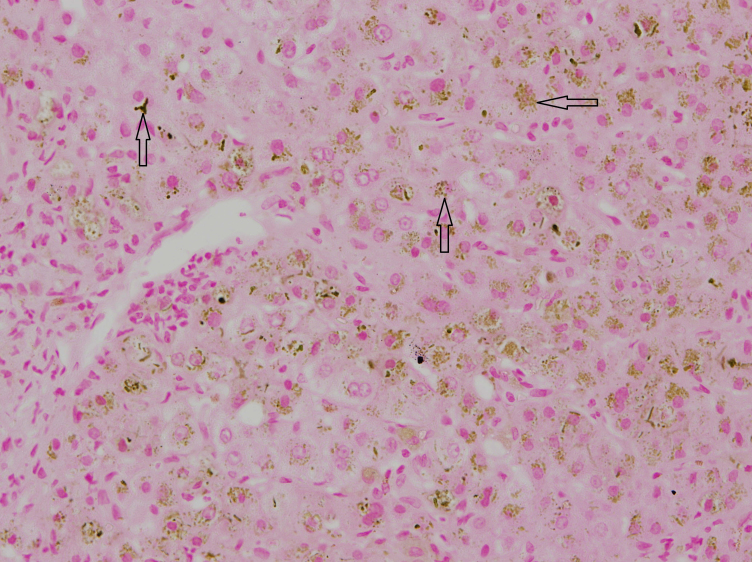

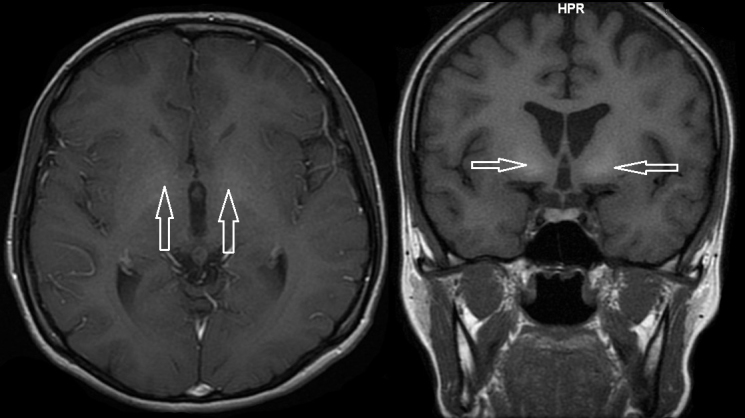

Hypoglycemia suggested the presence of insulinoma. The fasting test, the gold standard in diagnostics for this tumor type, had to be stopped after 36 hours because of sudden presyncope with neuroglycopenia and the features of enhanced sympathetic tone. However, the result of the test excluded the insulinoma diagnosis because in conditions of low glycemia (42 mg/dL), serum levels of insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin were undetectable and concentration of β-hydroxybutyric acid was not decreased. Simultaneously performed biochemical diagnostics suggested Wilson’s disease: decreased levels of ceruloplasmin (140 mg/L, normal values: 200-600), an increased concentration of free copper (17 µg/dL, normal values: less than 10), an increased 24-hour urine copper excretion (131 µg/24h, normal values <80), the presence of Kayser-Fleischer ring in the cornea (Figure 1), and an abnormal signal from basal ganglia (Figure 2). The ultrasound and MRI images of the liver were normal. Doppler ultrasound revealed only discrete features of portal hypertension without esophageal varices in endoscopic examination. Wilson’s disease was confirmed by liver biopsy (Figure 3), increased hepatic copper (320 µg/g dry weight), and identification of H1069Q mutation in the gene ATP7B. Because of the Wilson’s disease diagnosis, d-penicillamine was administered, which was later replaced (due to thrombocytopenia) with zinc acetate (150 mg/day in three divided doses). Hypoglycemic symptoms occurred twice at the initiation of the treatment, but subsided after 2 months of continuous therapy. After 4 months of treatment, menstruation returned while galactorrhea disappeared. Control MRI of pituitary gland did not reveal any abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Copper deposits in the posterior limiting lamina (Descemet’s membrane) of the cornea (Kayser-Fleischer ring).

Figure 2.

Hyperintensity of the caudate nuclei on magnetic resonance imaging (spin-echo T1 sequence).

Figure 3.

Core needle biopsy of the liver. Orcein staining revealed hepatic copper accumulation.

Discussion

The presented above case of a young woman indicates that there is a possibility of the initial endocrine manifestation of Wilson’s disease, suggesting the coexistence of prolactinoma and insulinoma. Although Wilson’s disease has been evidenced to cause the development of hypoglycemia [2], galactorrhea, and abnormal menstruation [4], these disturbances manifested in the advanced stages of the disease and were accompanied by the clinical picture of overt hepatolenticular degeneration [2]. Hypoglycemia usually developed as a result of cirrhosis-induced hepatic failure. On the other hand, menstrual abnormalities (except one case) [5] were secondary to hypoestrogenism induced by a reduction in ovarian aromatase activity, and therefore they were not accompanied by galactorrhea [4]. Interestingly, the lack of a typical clinical presentation of Wilson’s disease, a normal morphological picture of the liver on USG and MRI, and only discrete features of portal hypertension (a poorly developed collateral circulation without esophageal varices in endoscopic examination) indicate that the observed symptoms in our patient appeared at the initial stages of the disease. Nevertheless, Kayser-Fleischer corneal ring, low plasma levels of ceruloplasmin, increased plasma levels of free copper, and an increased urine excretion of this element show that even in the initial stage, establishing the correct diagnosis is possible.

Time parallelism between the regression of hypoglycemia, galactorrhea, menstrual abnormalities, and the eventual improvement in the clinical state not only strongly suggests the relationship between clinical picture of the patient and Wilson’s disease, but also excludes that the presented symptoms resulted from concomitant disorders. Efficacy of zinc preparations, which through metallothionein enhance copper binding and thereby inhibit copper absorption in enterocytes [1], also indicates that endocrine symptoms may be reversible if therapy is introduced early.

Galactorrhea and menstrual abnormalities in connection with the presence of a hypointense lesion in the pituitary suggested prolactinoma. However, normal plasma prolactin concentration excluded this diagnosis. Furthermore, normal plasma levels of growth hormone (GH), ACTH, FSH, LH, and TSH contradicted any other hormonal activity of the microadenoma. No abnormalities in the pituitary gland on the control MRI, performed after 6 months of therapy with zinc acetate, indicate that the pituitary lesion present in the onset probably corresponded to local copper accumulation, which receded as a result of treatment. The above-mentioned explanation is in agreement with observations of other authors [6], who found an abnormal response of lactotropes to gonadoliberin due to copper deposits in the pituitary gland of male patients with Wilson’s disease.

A very similar clinical picture of our patient to this observed in hyperprolactinemia may suggest an increased susceptibility of glandular tissue to prolactin, due to elevated copper accumulation in mammary gland. Several facts indirectly confirm this interpretation. To begin, zinc acetate caused the clinical improvement of patient state, although there was no clear influence of this form of therapy on prolactin concentration. Subsequently, although bromocriptine did not bring satisfactory effects, it caused limited clinical improvement. These findings may explain the abnormal prolactin-prolactin receptor interaction in peripheral tissues. Finally, prolactin enhances copper transport in glandular cells of the breast, which strongly suggests the existence of the interaction between copper and prolactin in the mammary gland [7]. It is possible that increased accumulation of copper in mammary tissues strengthens the local action of prolactin in this gland. Interestingly, if similar hypersensitivity occurs in the gonads, it may explain ultrasound picture of PCOS, despite normal secretion of androgens and gonadotropins.

In our patient, we observed Whipple’s triad: 1) clinical symptoms of neuroglycopenia and catecholamine excess induced by fasting or exertion; 2) low glucose levels (<45 mg/dL) associated with clinical signs of hypoglycemia; and 3) reversal of symptoms after meal consumption [8]. The only differences compared to the clinical picture of insulinoma were the age of the patient (insulinoma usually manifests between 40 and 60 years of age) and the lack of weight gain, observed in fewer than 30 percent of patients with insulinoma. Thus, the case presented herein indicates that Whipple’s triad cannot be treated as patognomic for insulinoma, and if no pathological changes in the pancreas are observed, it requires further diagnostics toward hepatolenticular degeneration. We presume that hypoglycemia resulted from hepatic dysfunction, caused by copper deposits in the liver that disturbed glucose metabolism regulation in this structure.

Conclusions

The presented above atypical course of Wilson’s disease confirms its complex symptomatology and evidences that hypoglycemia and galactorrhea of undefined etiology may indicate hepatolenticular degeneration. Furthermore, it should be taken into account even when typical clinical symptoms of this disease are absent, whereas image and hormonal examination are within normal range.

Abbreviations

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- USG

ultrasonography

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- GH

growth hormone

Disclaimer

Previously, we published two papers, both in Polish (Pol Arch Med Wewn (2007), Pol Merkur Lekarski (2008)), related to the same patient. Their content is, however, different from the content of this case report, and they do not contain any graphical presentation.

References

- Schilsky ML. Wilson disease: current status and the future. Biochimie. 2009;91:1278–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Youssef M. Wilson disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1126–1136. doi: 10.4065/78.9.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langner C, Denk H. Wilson disease. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushansky A, Frydman M, Kaufman H, Homburg R. Endocrine studies of the ovulatory disturbances in Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration) Fertil Steril. 1987;7:270–273. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)50004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkan T, Aktuglu C, Gulcan EM, Kutlu T, Cullu F, Apak T. et al. Wilson disease manifested primarily as amenorrhea and accompanying thrombocytopenia. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:378–380. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman M, Kauschansky A, Bonne-Tamir B, Nassar F, Homburg R. Assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in male patients with Wilson’s disease. J Androl. 1991;12:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher SL, Lönnerdal B. Mammary gland copper transport is stimulated by prolactin through alterations in Ctr1 and Atp7A localization. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1181–R1191. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00206.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JJ, Gorden P, Libutti SK. Insulinoma: pathophysiology, localization and management. Future Oncol. 2010;6:229–237. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]