Abstract

Fluorocarbons are quintessentially man-made molecules, fluorine being all but absent from biology. Perfluorinated molecules exhibit novel physicochemical properties that include extreme chemical inertness, thermal stability, and an unusual propensity for phase segregation. The question we and others have sought to answer is to what extent can these properties be engineered into proteins? Here, we review recent studies in which proteins have been designed that incorporate highly fluorinated analogs of hydrophobic amino acids with the aim of creating proteins with novel chemical and biological properties. Fluorination seems to be a general and effective strategy to enhance the stability of proteins, both soluble and membrane bound, against chemical and thermal denaturation, although retaining structure and biological activity. Most studies have focused on small proteins that can be produced by peptide synthesis as synthesis of large proteins containing specifically fluorinated residues remains challenging. However, the development of various biosynthetic methods for introducing noncanonical amino acids into proteins promises to expand the utility of fluorinated amino acids in protein design.

Keywords: fluorinated amino acids, 4-helix bundle proteins, protein stability, protein design, antimicrobial peptides, fluorous separations

Introduction

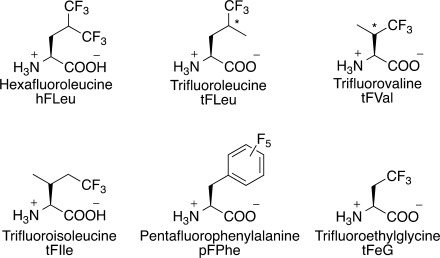

Protein engineering has relied heavily on mutagenesis, both site-directed and random, as a tool to modify the structure and function of enzymes and proteins. Until recently, this approach was limited to substitutions within the 20 natural (proteogenic) amino acids or post-translational chemical modification of protein structure. However, the development of various methods that allow a wide variety of non-natural, or nonproteogenic, amino acids to be incorporated into proteins has expanded the possibilities for modifying protein structure enormously. In particular, it is now possible to introduce a diverse range of chemical functionalities into proteins that are not seen in nature. Prominent among the non-natural amino acids that have been investigated are highly fluorinated analogs of hydrophobic amino acids, representatives of which are shown in Figure 1. These have attracted interest because of the unusual physicochemical properties of perfluorocarbons and their potential to enhance the stability of natural proteins.

Figure 1.

Fluorocarbon analogs of hydrophobic amino acids that have been incorporated into proteins; the abbreviations given are those used in this review. (*denotes a racemic stereocenter).

The unique physical properties of fluorinated molecules derive, in part, from the extreme electronegativity of fluorine. A C–F bond is polarized in the opposite direction to a C–H bond, and is both more stable, by about 14 kcal/mol, and less polarizable than a C–H bond. Fluorine is often considered isosteric with hydrogen as the van der Waals radius of fluorine, 1.35 Å, is only slightly greater than that of hydrogen, 1.2 Å; however, the C–F bond is significantly longer, ∼1.4 Å, than a C–H bond, ∼1.0 Å. Nevertheless, fluorine can frequently be substituted for hydrogen in small molecules, with minimal impact on their binding to proteins and enzymes. This property has been widely exploited to increase the hydrophobicity of pharmaceuticals and improve their bioavailability.1

Perfluorocarbons are highly chemically inert and extremely hydrophobic; for example, solvent partitioning experiments have shown a trifluoromethyl group to be twice as hydrophobic as a methyl group.2 They also exhibit unusual phase segregating properties; for example, water, hexane, and perfluorohexane are each mutually immiscible, and may therefore be described as both hydrophobic and lipophobic. This unusual property, which is known as the “fluorous effect,” underlies the nonstick properties of materials such as polytetrafluoroethylene. It has also been exploited in organic synthesis to extract molecules equipped with fluorocarbon tags from multicomponent reaction mixtures into perfluorocarbon solvents,3, 4 as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The fluorous effect in small molecules and proteins. (A) Triphasic mixtures are formed when fluorinated (green layer) solvents are mixed with aqueous (blue layer) and hydrocarbon (yellow layer) solvents. Solvent immiscibility can be used as a purification technique, when small molecules (purple spheres) are tagged with hydrocarbon (black) or fluorocarbon (green) tails. (B) It has been proposed that this property of fluorocarbons could be extended to the design of self-segregating proteins with either fluorinated (green) or nonfluorinated (yellow) hydrophobic cores.

Fluorine is essentially absent from biology, making the introduction of man-made fluorinated amino acids a unique way to modify proteins. Fluorinated amino acids have long been used as a sensitive and nonperturbing NMR probes to examine changes in local protein environment and dynamics.5–12 However, this review focuses on the more recent use of fluorine to modulate the physicochemical properties of proteins by incorporating highly fluorinated analogues of hydrophobic amino acids, in particular leucine, isoleucine, valine, and phenylalanine, into their structures.13–15 Such proteins exhibit increased stability towards unfolding by chemical denaturants, solvents and heat, and degradation by proteases. It has also been postulated that a protein-based fluorous effect could be created by incorporating highly fluorinated residues at protein interfaces, thereby introducing an interaction orthogonal to the hydrophobic effect with which to direct protein recognition and ligand binding (Fig. 2).

Synthesis of Highly Fluorinated Proteins

The incorporation of any nonproteogenic amino acid into a protein poses a synthetic challenge. It has been known for a long time that sparingly fluorinated analogs of many hydrophobic amino acids can be incorporated biosynthetically with high efficiency using bacterial strains that are auxotrophic for the parent amino acid.16, 17 However, extensively fluorinated amino acids are generally not recognized by the endogenous protein synthesis machinery. Therefore, most studies on highly fluorinated proteins have focused on short proteins and peptides and utilized solid phase peptide synthesis to introduce fluorinated residues, which is straightforward and provides a great deal of flexibility.

Alternatively, Tirrell and coworkers have developed methods for residue specific incorporation of fluorinated amino acids such as trifluoroleucine (tFLeu), trifluoroisoleucine (tFIle), and trifluorovaline (tFVal) that can be activated by endogenous tRNA synthetases. The advantage of this method is that large proteins can be fluorinated; however, protein expression does not result in 100% incorporation of fluorinated analogs due to the presence of natural amino acid substrate derived from cellular proteins; efficiencies of 70–90% are typical. In vivo protein incorporation also results in global substitution of a particular amino acid, which limits some applications. Highly fluorinated analogs such as hexafluoroleucine (hFLeu) are not efficiently recognized by tRNA synthetases, and thus not incorporated in vivo. However, this limitation has been overcome by over-expression in E. coli of an engineered leucyl-tRNA synthetase that activates hFleu with improved efficiency.17–20

In principle, fluorous amino acids could be introduced biosynthetically in a site-specific manner using an evolved orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair, an approach which has been pioneered by Schultz and coworkers.21, 22 To our knowledge, it has not been used so far to produce highly fluorinated proteins, presumably because of the technical barrier presented by the need to evolve the requisite tRNA synthetase. Similarly, expressed protein ligation techniques23, 24 offer a way to produce semisynthetic proteins that contain segments of non-natural residues, but again this technique has not yet been used for the production of extensively fluorinated proteins.

Stabilizing Proteins Through Fluorination

The hydrophobic effect is the major driving force in protein folding, so it is not surprising that fluorinated amino acids, being more hydrophobic than their hydrocarbon counterparts, are generally effective in stabilizing protein structure. For example, solvent partitioning studies predict that the increased hydrophobicity of hFLeu can stabilize a protein by ∼0.4 kcal/mol/residue over Leu, although predicted stability increases for proteins as high as 1.1 kcal/mol/hFLeu residue have been reported.25, 26 Most studies have focused on the incorporation of fluorinated analogs of valine, leucine, and isoleucine into the hydrophobic core of small α-helical proteins. In addition, the effect of fluorination on the stability of β-sheet proteins, transmembrane proteins, and other small globular proteins has also been studied.

Studies on parallel coiled-coil proteins

The first reports of fluorous amino acids enhancing the stability of proteins came from laboratories of Kumar, Tirrell and coworkers, who studied the effects of fluorination on the coiled-coil domain of GCN4 and a de novo-designed coiled-coil dimer, A1. Substituting the four Leu and three Val residues in GCN4 [Fig. 3(A)] by tFLeu and tFVal respectively resulted in a relatively modest stabilization of ∼1 kcal/mol over the nonfluorinated version.27 Substituting the six core d-position leucine residues of A1 by tFLeu resulted in a protein that was 0.4 kcal/mol/tFLeu residue more stable.17 Whereas increasing the fluorine content of A1 by substituting hFLeu for Leu resulted in a correspondingly higher stabilization of A1 by ∼0.6 kcal/mol/hFLeu residue.28 Fluorinated versions of the coiled-coil DNA binding protein, GCN4-bZip, and its dimerization subdomain GCN4-p1d have been produced synthetically.18 In this case, substituting tFLeu for four d-position Leu residues of GCN4-p1d substantially increased the thermal stability of the protein and provided a modest increase in the free energy of unfolding, ΔΔGunfold ∼0.6 kcal/mol. Importantly, the fluorinated GCN4-bZip retained the ability of the wild-type protein to bind DNA, suggesting that fluorination may be a general strategy for increasing stability without compromising biological activity.

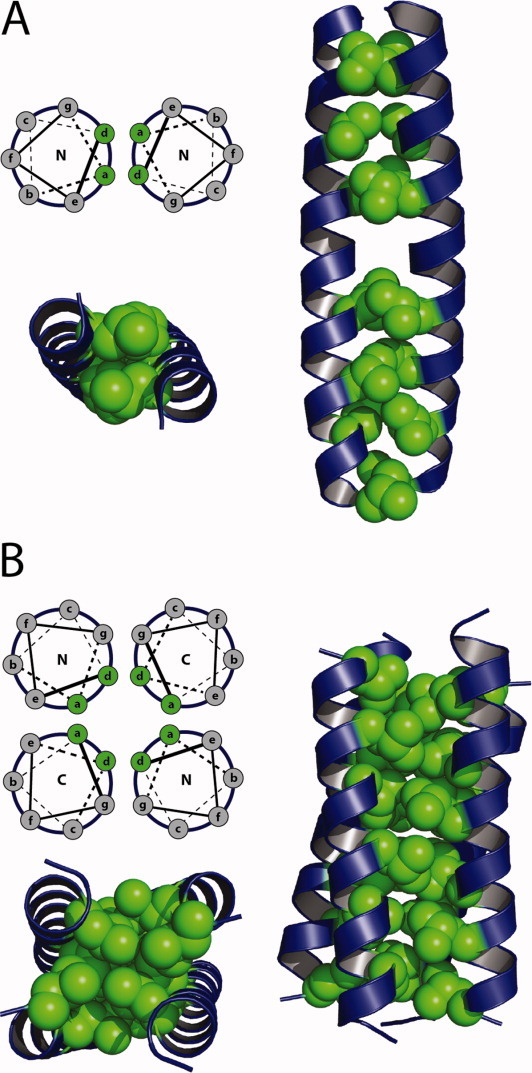

Figure 3.

Coiled-coil proteins used as model systems to study the effects of fluorination. (A) Helix wheel diagram demonstrating the heptad repeat and hydrophobic packing of the parallel coiled-coil GCN4. Three-dimensional representation of GCN4 indicating the seven a and d positions which have been modified with fluorinated residues. (B) Helix wheel diagram demonstrating the heptad repeat and hydrophobic packing of the antiparallel coiled-coil α4. Three-dimensional representation of α4 indicating the six a and d positions which have been modified with fluorinated residues.

Further studies on the biosynthetic incorporation of fluorous amino acids examined the stereochemical preference of tRNA-synthetases for stereoisomers of tFVal, tFLeu and tFIle. Studies using purified valyl- and isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase demonstrated, somewhat surprisingly, that (2S,3R)-tFVal was recognized by both enzymes with similar efficiency, whereas the (2S,3S)-isomer was inactive.20, 29 In vivo incorporation of tFVal into murine dihydrofolate reductase gave similar results with (2S,3R)-tFVal being incorporated into both valine and isoleucine positions in the enzyme.20 Similarly, it was shown that the isoleucine analog 5-tFIle was efficiently recognized by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase and incorporated into proteins, whereas the structural isomer 3-tFIle was not recognized.19 The leucyl-tRNA synthetase seems to be less discriminating towards side-chain fluorination as both (2S,4S)-tFLeu and (2S,4R)-tFLeu were biosynthetically incorporated into the coiled-coil protein, A1 with similar efficiency.30

Studies on antiparallel coiled-coil proteins

Studies in our laboratory to understand the effects of fluorination on the physical and biological properties of proteins have utilized a de novo designed antiparallel 4-α-helix bundle protein, α4. α4H, the parent protein, contains Leu at the three a and three d positions of the heptad repeat, which forms the hydrophobic core of the folded tetramer [Fig. 3(B)].25, 31 In various studies, we have synthesized a number of fluorinated versions of α4, designated α4Fn, that incorporate hFLeu at different positions within the core and examined their physical and biological properties. In all cases these proteins retain well-folded, native-like properties despite the fact that the hFLeu side-chain is ∼30% larger than Leu.

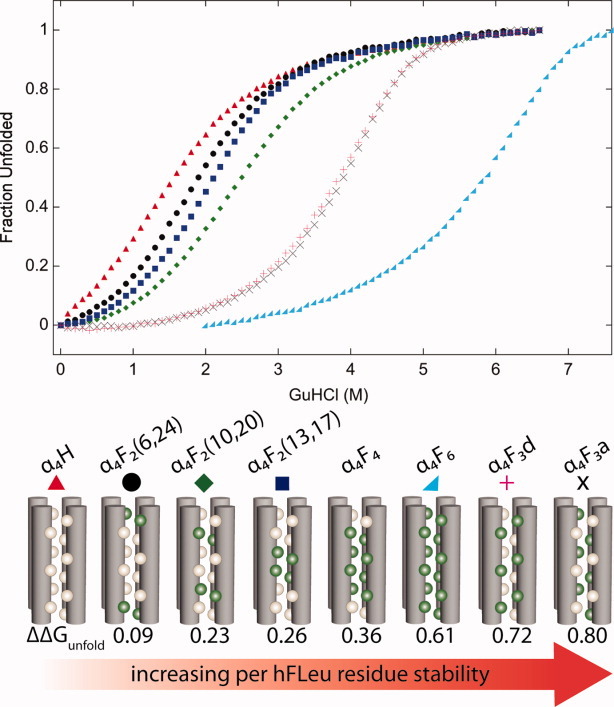

The stability of the α4F proteins progressively increases as the number of hFLeu residues increases, so that α4F6, in which all the Leu residues are replaced by hFLeu, is 14.8 kcal/mol more stable than α4H; a per residue increase of 0.6 kcal/mol/hFLeu. The position and pattern of the hFLeu substitutions also has an effect on the stability of the protein (Fig. 4). For the series of α4F2 proteins, each of which contain two hFLeu residues per strand, the stability increases from 0.09 to 0.26 kcal/mol/hFLeu as the hFLeu residues are progressively moved from the more solvent-exposed ends of the bundle to the solvent-excluded center of the bundle.32 The most stabilizing arrangement of hFLeu and Leu residues seems to be an alternating pattern in which hFLeu is incorporated at a positions and Leu at d positions, or vice versa. Thus α4F3a, which contains hFLeu residues in all a positions, is more stable than α4H by 0.8 kcal/mol/hFLeu residue. This result points to the importance of considering packing effects, and not just the degree of fluorination, when designing ultra-stable fluorinated proteins

Figure 4.

Thermodynamic stability of hFLeu substituted α4 proteins. (Top) GuHCl induced unfolding of α4 proteins followed by circular dichroism at 222 nm, protein identities are listed in the center. (Bottom) Cartoons illustrating the packing of α4 proteins with Leu as tan spheres and hFLeu as green spheres. Fluorination greatly increases protein stability, ΔΔGunfold (kcal/mol/hFLeu residue) shown as increasing from left to right.

Focusing on the α4F6 protein, we have also examined how fluorination alters its resistance to solvent denaturation and degradation by proteases, properties which may have practical applications. In water-alcohol mixtures containing methanol, ethanol or 2-propanol α4F6 retains its helical structure whereas α4H, which is itself quite a stable protein, becomes increasingly more unfolded as the hydrophobic nature of the solvent increases.33 Contrary to the behavior predicted by the fluorous effect, fluorinated solvents, such as trifluoroethanol or hexafluoro-2-propanol do not preferentially unfold α4F6 but cause it to dissociate into highly helical monomers; these fluorinated solvents have a similar effect on α4H, consistent with their well-documented ability to increase the helicity of a large number of peptides.

We have also found that fluorination protects α4F6 against proteolysis. Whereas α4H was nearly completely degraded in ∼2 hours by either trypsin or chymotrypsin, far less proteolysis of α4F6 was observed under the same conditions. This likely reflects a much slower rate of unfolding by the more thermodynamically stable fluorinated protein rather than the inability of proteases to act on fluorinated substrates.

Context effects

Whereas studies on coiled-coil proteins have found that fluorinated leucine analogs invariably confer greater stability, an interesting study by Cheng and coworkers has concluded that, in the context of a single helix, hFLeu is actually destabilizing relative to Leu.34 Using a monomeric, alanine-based model helix, various fluorinated and hydrocarbon side-chains were introduced into a central “guest” position. The helicity of these peptides was then compared relative to alanine at the guest position. Comparing the helicity of ethylglycine with trifluoroethylglycine (tFeG), Leu with hFLeu, and Phe with pFPhe, the fluorocarbon amino acids were found to be significantly less helical than their hydrocarbon counterparts. In the case of hFLeu, the helix propensity is decreased eightfold compared to Leu, corresponding to an energetic penalty of 1.15 kcal/mol/hFLeu. The decrease in helical content is surprising given that fluorinated amino acids are stabilizing in helical coiled-coils.

Equally surprising is that in the context of a β-sheet, fluorinated residues in solvent-exposed positions seem to stabilize the folded state.35 Evidence for this comes from experiments in which hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon residues were introduced at a solvent-exposed position on an internal strand of a β-sheet in the small protein GB1. The fluorinated residues tFeG, hFLeu, and pFPhe each increased the protein's stability by ∼0.3 kcal/mol over their hydrocarbon counterparts. The reason that fluorination seems to exert opposite effects on protein stability in the context of an α-helix versus in a β-sheet is unclear. Moreover, the stabilizing potential of fluorinated amino acids in β-sheets has largely been overlooked, making this an interesting avenue for future research.

Koksch and coworkers have studied how the spatial demands and polarity of fluorinated residues influence the properties of proteins in a model antiparallel coiled-coil protein.36–38 They have looked at ethylglycine and its fluorinated analogues: difluoroethylglycine (dFeG), trifluoroethylglycine (tFeG), and difluoropentylglycine (dFpG). This variety of small fluorinated amino acids allows variation in hydrophobic volume and side chain polarity for the tuning of stability in protein design. Analogs of the native antiparallel dimer showed decreased stability when any of the fluorinated amino acids were substituted for Leu9 in the hydrophobic core or solvent exposed Lys8. These results demonstrate a decrease in stability due to both decreased hydrophobic volume and changes in polarity of the hydrophobic core.

Studies on more complex protein structures

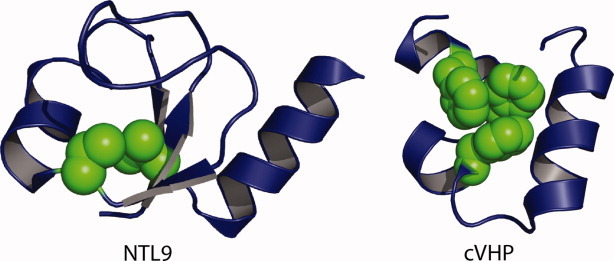

Although most studies have focused on simple α-helical proteins, the effects of fluorination on other protein folds have also been investigated. In one case, the effect of substituting two valine residues by tFVal on the folding kinetics and stability of the globular α-β protein NTL9 (Fig. 5) was investigated. The small isosteric change to the core of the globular protein NTL9 did not disrupt the native fold but significantly changed the stability and folding kinetics. At one position, introduction of tFVal increased the stability of the protein by 1.4 kcal/mol/tFVal residue.39 Fluorination resulted in a marked decrease in the unfolding rate and a slight increase in the folding rate. The change in folding kinetics was attributed to the increased hydrophobicity of the trifluoromethyl group stabilizing the transition state for folding.

Figure 5.

Fluorinated proteins with more complex folds. (Left) Model of NTL9 illustrating positions Val3 and Val21 in green, which were substituted by tFVal. (Right) Model of cVHP demonstrating packing interactions of core Phe residues in green.

Other studies have investigated the 35-residue independently folded “headpiece” subdomain of chicken villin protein (cVHP), which has three phenylalanine residues in the hydrophobic core (Fig. 5).40, 41 When these were substituted by pentafluorophenylalanine (pFPhe),40 only at one position did the substitution stabilize the protein, whereas at the other two positions pFPhe was actually destabilizing. This could be due to steric effects caused by the larger volume of pFPhe and/or due to changes in the quadrupole moment of the aromatic ring induced by fluorination—whereas a phenyl ring has an electron-rich center and a correspondingly electron-poor periphery, the high electronegativity of fluorine results in the center of the ring being electron-poor and periphery being electron-rich. In contrast, large stability increases were observed when residues in the aromatic core of cVHP were replaced by tetrafluorophenylalanine, which were attributed to favorable polar interactions between aromatic hydrogens and π-electrons.41

Quadupole-quadrupole interactions can make important contributions to protein structure. The energetic contribution of the quadrupole interaction between a Phe-pFPhe pair in a de novo designed, dimeric, 4-helix bundle protein designated α2D was investigated by Zheng and Gao.42 The protein was designed to assemble from two peptides; one containing two Phe residues at core positions, the other containing two pFPhe residues. Mixing the peptides resulted in a single, stable species with assembly directed by the introduced quadrupole interactions. By analyzing the folding energies through the use of a double-mutant cycle, the stabilization due to the quadrupole interaction, ΔGquad was estimated to be ∼1.0 kcal/mol/Phe-pFPhe pair. Further stabilization studies of α2D by systematic substitution of the stacked core phenylalanine residues with mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentafluorophenylalanine demonstrated that a combination of dipole–dipole coupling and hydrophobics contribute to stability.43 This study identified the phenylalanine/ortho-tetrafluorophenylalanine as being the most stable aromatic pair with ΔΔGfold of 6.7 kcal/mol. These studies underscore how fluorine modification of aromatic residues allows alteration of van der Waals, hydrophobic and electrostatic forces to modify protein stability.

The potential for fluorous effects in fluorinated proteins

The unusual tendency of fluorocarbons to self-associate, leading to phase separation of fluorocarbon and hydrocarbon solvents, gave rise to the intriguing possibility that highly fluorinated proteins might possess similar properties. In proteins, the fluorous effect might result in specific protein–protein interactions through fluorous contacts between side-chains that would be orthogonal to normal protein–protein interactions. However, evidence for self-segregating properties of fluorinated proteins is mixed and may be protein fold dependent. There is still some debate as to whether in the context of fluorous proteins the fluorous effect is a driving force for stability or if the increased hydrophobic volume is the main stability contributor.

Kumar and coworkers have demonstrated the preferential interaction of a fluorinated parallel coiled-coil dimer in both aqueous and membrane environments.44–47 These experiments used peptides that contained either Leu or hFLeu at the hydrophobic a and d positions that comprise the core of the coiled-coil and Cys residues at their N-termini. Disulfide bond formation allowed the two partner peptides in the coiled-coil to be covalently cross-linked and analyzed. It was found that the peptides preferentially self-segregated into fluorinated (FF) and nonfluorinated (HH) coiled-coils with less than 3% of peptides forming heterodimers (Fig. 6).44 However, the interpretation of this experiment is complicated by the fact that the fluorinated peptide formed a tetramer rather than the intended dimer. It may be simply that the bulkier hFLeu side chain was not compatible with the hydrophobic core of a dimeric coiled-coil.

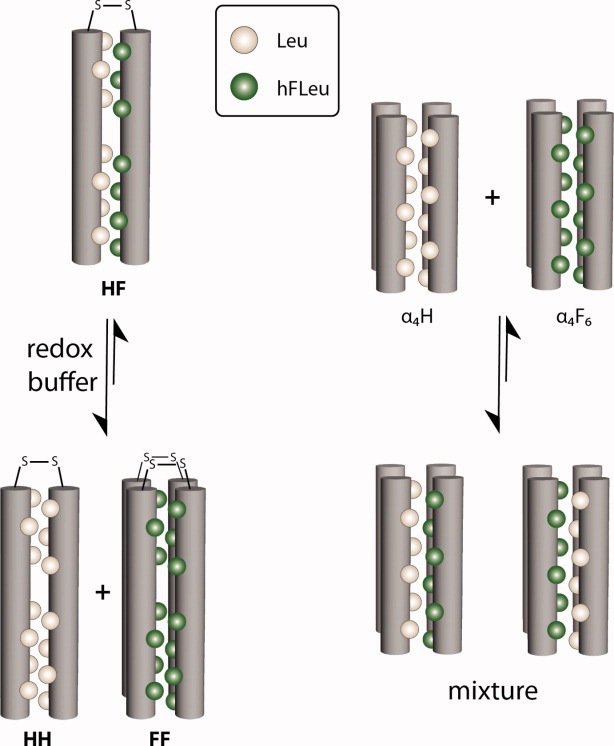

Figure 6.

Evaluating “fluorous” self-assembly in two different protein systems. (Left) The disulfide-linked “mixed” protein HF self-segregates into equilibrium populations containing all-Leu cores, HH, and all-hFLeu cores, FF, in the presence of a redox buffer. (Right) Upon combining α4H, which contains an all-Leu core, and α4F6, which contains an all-hFLeu core, mixtures of protein tetramers are observed, indicating a lack of fluorous segregation.

The self-association of fluorinated peptides designed to form transmembrane helices has also been demonstrated. Again, the peptides were designed to form parallel coiled-coils containing seven Leu or hFLeu at a and d positions, but in this case the peptides were labeled with a fluorophore and FRET used to determine whether the fluorinated and nonfluorinated peptides interacted. Similar to the soluble coiled-coils, the fluorinated and nonfluorinated transmembrane peptides seemed to preferentially self-associate; however, again, whereas the nonfluorinated peptide was dimeric, the fluorinated peptide adopted a tetrameric structure. The results were interpreted as the fluorocarbon side chains forming an interface orthogonal to that of hydrocarbon lipid chains and protein side-chains.

Our laboratory has investigated the segregation of fluorinated and hydrocarbon versions of the de novo designed α4 proteins, which form antiparallel 4-helix bundles (Fig. 6). This motif has proved highly robust, and α4 tolerates fluorination without changing its quaternary structure. In this system, we found little or no evidence that these peptides undergo self-segregation, contrary to the predictions of the fluorous effect. Two experiments in particular point to the absence of preferential fluorous interactions.

In one experiment, we used 19F NMR to examine the interactions between α4H, which contains Leu at all the a and d positions, and α4F6 which contains hFLeu at all the a and d positions.33 α4F6 has a complex 19F NMR spectrum that reflects the high sensitivity of the 19F nucleus to slight differences in the chemical environments of the hFLeu –CF3 groups. Titrating α4F6 with increasing concentrations of α4H resulted in progressive changes to the 19F NMR spectrum, with the signals becoming less disperse and shifting downfield as α4H ratio was increased. Sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation measurements indicated that the peptide mixtures remained tetrameric. Clearly, no change in the 19F spectrum would be expected unless the α4F6 and α4H peptides were interacting, so these results indicate that the peptides form heterotetramers in which the monomers exchange on the NMR timescale.

Further evidence against the idea that fluorine-fluorine contacts per se can be used to engineer orthogonal interactions between proteins comes from proteins with mixed hydrocarbon-fluorocarbon cores.32 α4F3a and α4F3d have hFLeu in all the a or all the d positions, respectively, which gives rise to a hydrophobic core in which fluorocarbon residues are interposed with hydrocarbon residues. These proteins are very stable and, on a per-hFLeu-residue basis, exceed the stability of the “all fluorine” protein α4F6. These results suggest that optimizing core packing to reduce steric hindrance and accommodate changes in side-chain volumes is more important for stability than potential self-segregating effects of fluorinated residues. The extent of any fluorous effect in fluorinated proteins is complicated by the fact that proteins rely on numerous weak interactions to specify their folded structures.

Modulating the properties of bioactive peptides

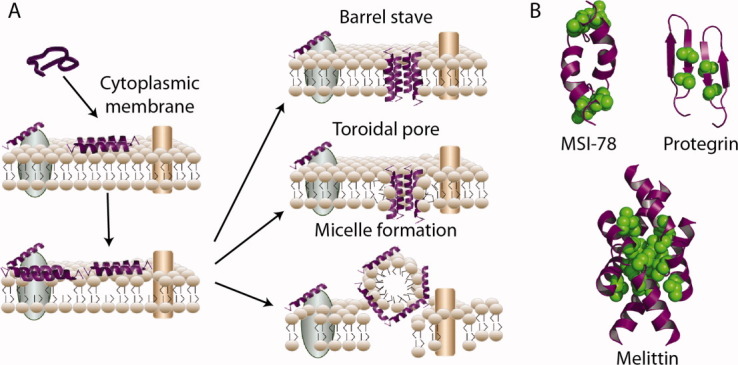

Fluorination has also been used as a tool to modify the properties of biologically active peptides and investigate their mechanism of action. In particular, some classes of peptides, notably antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and venom peptides, exert their biological effect through direct disruption of cell membranes, rather than specific peptide-protein or peptide-nucleic acid interactions. This disruptive effect depends on the overall balance of positively charged and hydrophobic residues, rather than sequence-specific interactions, making fluorination an ideal method to alter the hydrophobicity of these peptides in a nondisruptive manner (Fig. 7). The incorporation of fluorinated residues also allows peptide-membrane interactions to be followed by 19F NMR.48, 49

Figure 7.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are components of the innate immune system that act by disrupting bacterial membranes. (A) Membrane disruption mechanism of AMPs is initiated by attraction of the positively charged peptide to the negatively charged bacterial membrane lipid headgroups. Loss of membrane integrity results from three distinct pore forming mechanisms. (B) Models of the AMPs, MSI-78 and protegrin-1, and venom peptide, melittin, with positions of fluorinated amino acid substitution shown in green.

Studies on an analog of the bee venom peptide, melittin, were among the first to show that incorporating fluorinated amino acids could modulate the biological activity of membrane-active peptides. Replacing four Leu residues with tFLeu in melittin resulted in increased partitioning of the fluorinated peptide into liposomes.50 In our laboratory, we have used fluorinated amino acids to modulate the biological activity of the potent synthetic AMP MSI-78 and probe its interactions with membranes.

In one study, we replaced the two Leu and two Ile residues in MSI-78 with hFLeu.51 Overall, the resulting highly fluorinated AMP, dubbed fluorogainin-1, exhibited very similar antimicrobial activity to MSI-78 against a broad range of bacteria. Interestingly, fluorogainin-1 displayed a significantly lower MIC against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus than MSI-78. Whereas antimicrobial activity was retained, fluorination seemed to alter the mechanism of membrane disruption. Differential scanning calorimetry measurements indicated that the parent peptide, MSI-78, induces positive membrane curvature consistent with a toroidal pore mechanism; in contrast, fluorogainin-1 induced negative membrane curvature indicative of the barrel-stave mechanism for membrane disruption.

In another study, we used fluorination to assess the effects of increasing hydrophobicity in protegrin-1 (PG-1), which is a potent member of the β-hairpin-forming class of antimicrobial peptides. By replacing two valine residues on the hydrophobic face of protegrin-1 with either two Leu or hFLeu residues52 we were able to progressively increase hydrophobicity although minimally perturbing secondary structure. The Leu containing-peptide was significantly more active than wild-type protegrin against several common pathogenic bacterial strains, whereas the hFLeu-substituted peptide, in contrast, showed significantly diminished activity against several bacterial strains. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements revealed significant changes in the interaction of the peptides binding to liposomes that mimic the lipid composition of the bacterial membrane. Notably, both these substitutions seem to alter the stoichiometry of the lipid-peptide interaction, suggesting that these substitutions may stabilize oligomerized forms of protegrin that are postulated to be intermediates in the assembly of the β-barrel membrane pore structure.

One significant obstacle to the therapeutic use of AMPs is the inherent susceptibility of peptides towards proteolysis. Strategies to increase proteolytic stability of peptide-based therapeutics include use of D-peptides, β-peptides and arylamide polymers.53–55 It also seems that incorporation of fluorinated amino acids provides a further means of stabilizing bio-active peptides that could increase their therapeutic index. Thus, when bound to liposomes, fluorogainin-1 proved far more resistant to proteolysis than MSI-78. Whereas MSI-78 was degraded by either trypsin or chymotrypsin in about 30 min, under the same conditions fluorogainin-1 exhibited no degradation after 10 hours. Similar results have been obtained with other membrane-active peptides, such as buforin and magainin,56 suggesting that fluorination may be a general strategy for prolonging the lifetime of peptides in vivo.

Kumar and coworkers have used hFLeu to stabilize glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which is a promising therapeutic to regulate blood glucose homeostasis to treat type 2 diabetes. Clinical applications of GLP-1 are severely limited due to degradation by the regulatory serine protease, dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Substituting any of the hydrophobic positions 8, 9, and 10 with hFLeu conferred resistance to proteolysis.57 However, fluorination seemed to reduce the affinity of the peptide for its receptor, possibly due to the increased volume of the hFLeu residues.

Conclusions

The development of new methods to incorporate noncanonical amino acids has ushered in a new era of protein design with novel side chain functionalities altering the chemistry of biology. Some of the unique physicochemical properties associated with fluorocarbons can be introduced into proteins, imparting them with useful characteristics—most notably increased structural stability. Highly fluorinated side-chains provide a valuable tool to modify protein stability with minimal perturbation of structure and function. We hope that the various examples of fluorinated proteins discussed in this review, demonstrates the utility of fluorination for increasing stability, probing biological mechanisms and developing novel therapeutic agents.

Our understanding of the physicochemical properties of extensively fluorinated proteins is far from complete and, in particular, is hindered by the absence of detailed structural information for any extensively fluorinated protein or peptide. Atomic level knowledge of how fluorinated residues are accommodated within a protein environment would aid the design of biomolecules with enhanced stability and raises the possibility of rationally designing unique protein-based fluorous phases. Obtaining X-ray structures of the fluorous proteins we have discussed in this review is a current goal in our laboratory. We are optimistic that such structures will be forthcoming in the near future.

References

- 1.Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnati G. Synthesis of chiral and bioactive fluoroorganic compounds. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:9385–9445. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horvath IT, Rabai J. Facile catalyst separation without water: fluorous biphase hydroformylation of olefins. Science. 1994;266:72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5182.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo Z, Zhang Q, Oderaotoshi Y, Curran DP. Fluorous mixture synthesis: a fluorous-tagging strategy for the synthesis and separation of mixtures of organic compounds. Science. 2001;291:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.1057567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ropson IJ, Frieden C. Dynamic NMR spectral analysis and protein folding: identification of a highly populated folding intermediate of rat intestinal fatty acid-binding protein by 19F NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7222–7226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerig JT. Fluorine NMR of proteins. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1994;26:293–370. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long GJ, Rosen JF, Schanne FA. Lead activation of protein kinase C from rat brain. Determination of free calcium, lead, and zinc by 19F NMR. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:834–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danielson MA, Falke JJ. Use of F-19 NMR to probe protein structure and conformational changes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:163–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duewel H, Daub E, Robinson V, Honek JF. Incorporation of trifluoromethionine into a phage lysozyme: implications and a new marker for use in protein 19F NMR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3404–3416. doi: 10.1021/bi9617973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gakh YG, Gakh AA, Gronenborn AM. Fluorine as an NMR probe for structural studies of chemical and biological systems. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:551–558. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luchette PA, Prosser RS, Sanders CR. Oxygen as a paramagnetic probe of membrane protein structure by cysteine mutagenesis and 19F NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1778–1781. doi: 10.1021/ja016748e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan F, Kuprov I, Craggs TD, Hore PJ, Jackson SE. 19F NMR studies of the native and denatured states of green fluorescent protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10729–10737. doi: 10.1021/ja060618u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh ENG. Towards the nonstick egg: designing fluorous proteins. Chem Biol. 2000;7:R153–R157. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jäckel C, Koksch B. Fluorine in peptide design and protein engineering. Eur J Org Chem. 2005;2005:4483–4503. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoder NC, Yüksel D, Dafik L, Kumar K. Bioorthogonal noncovalent chemistry: fluorous phases in chemical biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennert OM, Anker HS. On the incorporation of 5′,5′,5′-trifluoroleucine into proteins of E. coli. Biochemistry. 1963;2:471–476. doi: 10.1021/bi00903a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Y, Ghirlanda G, Petka WA, Nakajima T, DeGrado WF, Tirrell DA. Fluorinated coiled-coil proteins prepared in vivo display enhanced thermal and chemical stability. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:1494–1496. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1494::AID-ANIE1494>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y, Ghirlanda G, Vaidehi N, Kua J, Mainz DT, Goddard WA, DeGrado WF, Tirrell DA. Stabilization of coiled-coil peptide domains by introduction of trifluoroleucine. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2790–2796. doi: 10.1021/bi0022588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P, Tang Y, Tirrell DA. Incorporation of trifluoroisoleucine into proteins in vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6900–6906. doi: 10.1021/ja0298287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang P, Fichera A, Kumar K, Tirrell DA. Alternative translations of a single RNA message: an identity switch of (2S,3R)-4,4,4-trifluorovaline between valine and isoleucine codons. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:3664–3666. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Xie J, Schultz PG. Expanding the genetic code. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:225–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.101105.121507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muir TW, Sondhi D, Cole PA. Expressed protein ligation: a general method for protein engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6705–6710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muir TW. Semisynthesis of proteins by expressed protein ligation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:249–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee K-H, Lee H-Y, Slutsky MM, Anderson JT, Marsh ENG. Fluorous effect in proteins: de novo design and characterization of a four-α-helix bundle protein containing hexafluoroleucine. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16277–16284. doi: 10.1021/bi049086p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pendley SS, Yu YB, Cheatham TE. Molecular dynamics guided study of salt bridge length dependence in both fluorinated and non-fluorinated parallel dimeric coiled-coils. Proteins. 2009;74:612–629. doi: 10.1002/prot.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilgiçer B, Fichera A, Kumar K. A coiled coil with a fluorous core. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4393–4399. doi: 10.1021/ja002961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Y, Tirrell DA. Biosynthesis of a highly stable coiled-coil protein containing hexafluoroleucine in an engineered bacterial host. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11089–11090. doi: 10.1021/ja016652k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Son S, Tanrikulu IC, Tirrell DA. Stabilization of bzip peptides through incorporation of fluorinated aliphatic residues. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1251–1257. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montclare JK, Son S, Clark GA, Kumar K, Tirrell DA. Biosynthesis and stability of coiled-coil peptides containing (2S,4R)-5,5,5-trifluoroleucine and (2S,4S)-5,5,5-trifluoroleucine. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:84–86. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H-Y, Lee K-H, Al-Hashimi HM, Marsh ENG. Modulating protein structure with fluorous amino acids: increased stability and native-like structure conferred on a 4-helix bundle protein by hexafluoroleucine. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:337–343. doi: 10.1021/ja0563410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buer BC, de la Salud-Bea R, Al Hashimi HM, Marsh ENG. Engineering protein stability and specificity using fluorous amino acids: the importance of packing effects. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10810–10817. doi: 10.1021/bi901481k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottler LM, de la Salud-Bea R, Marsh ENG. The fluorous effect in proteins: properties of α4F6, a 4-α-helix bundle protein with a fluorocarbon core. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4484–4490. doi: 10.1021/bi702476f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu H-P, Suzuki Y, Gullickson D, Ahmad R, Kokona B, Fairman R, Cheng RP. Helix propensity of highly fluorinated amino acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15556–15557. doi: 10.1021/ja0640445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiu H-P, Kokona B, Fairman R, Cheng RP. Effect of highly fluorinated amino acids on protein stability at a solvent-exposed position on an internal strand of protein G B1 domain. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13192–13193. doi: 10.1021/ja903631h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jäckel C, Seufert W, Thust S, Koksch B. Evaluation of the molecular interactions of fluorinated amino acids with native polypeptides. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:717–720. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jäckel C, Salwiczek M, Koksch B. Fluorine in a native protein environment—how the spatial demand and polarity of fluoroalkyl groups affect protein folding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:4198–4203. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salwiczek M, Koksch B. Effects of fluorination on the folding kinetics of a heterodimeric coiled coil. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2867–2870. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horng J-C, Raleigh DP. ϕ-Values beyond the ribosomally encoded amino acids: kinetic and thermodynamic consequences of incorporating trifluoromethyl amino acids in a globular protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9286–9287. doi: 10.1021/ja0353199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woll MG, Hadley EB, Mecozzi S, Gellman SH. Stabilizing and destabilizing effects of phenylalanine → F5-phenylalanine mutations on the folding of a small protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15932–15933. doi: 10.1021/ja0634573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng H, Comeforo K, Gao J. Expanding the fluorous arsenal: tetrafluorinated phenylalanines for protein design. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;131:18–19. doi: 10.1021/ja8062309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng H, Gao J. Highly specific heterodimerization mediated by quadrupole interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:8635–8639. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pace CJ, Zheng H, Mylvaganam R, Kim D, Gao J. Stacked fluoroaromatics as supramolecular synthons for programming protein dimerization specificity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:103–107. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilgiçer B, Xing X, Kumar K. Programmed self-sorting of coiled coils with leucine and hexafluoroleucine cores. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11815–11816. doi: 10.1021/ja016767o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bilgiçer B, Kumar K. Synthesis and thermodynamic characterization of self-sorting coiled coils. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:4105–4112. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bilgiçer B, Kumar K. De novo design of defined helical bundles in membrane environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403314101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naarmann N, Bilgiçer B, Meng H, Kumar K, Steinem C. Fluorinated interfaces drive self-association of transmembrane α helices in lipid bilayers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:2588–2591. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buer BC, Chugh J, Al-Hashimi HM, Marsh ENG. Using fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance to probe the interaction of membrane-active peptides with the lipid bilayer. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5760–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi100605e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki Y, Buer BC, Al-Hashimi HM, Marsh ENG. Using fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance to probe changes in the structure and dynamics of membrane-active peptides interacting with lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5979–5987. doi: 10.1021/bi200639c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niemz A, Tirrell DA. Self-association and membrane-binding behavior of melittins containing trifluoroleucine. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7407–7413. doi: 10.1021/ja004351p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottler LM, Lee H-Y, Shelburne CE, Ramamoorthy A, Marsh ENG. Using fluorous amino acids to modulate the biological activity of an antimicrobial peptide. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:370–373. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gottler LM, de la Salud Bea R, Shelburne CE, Ramamoorthy A, Marsh ENG. Using fluorous amino acids to probe the effects of changing hydrophobicity on the physical and biological properties of the β-hairpin antimicrobial peptide protegrin-1. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9243–9250. doi: 10.1021/bi801045n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bessalle R, Kapitkovsky A, Gorea A, Shalit I, Fridkin M. All-D-magainin: chirality, antimicrobial activity and proteolytic resistance. FEBS Lett. 1990;274:151–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81351-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu D, DeGrado WF. de novo design, synthesis, and characterization of antimicrobial β-peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7553–7559. doi: 10.1021/ja0107475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi S, Isaacs A, Clements D, Liu D, Kim H, Scott RW, Winkler JD, DeGrado WF. De novo design and in vivo activity of conformationally restrained antimicrobial arylamide foldamers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6968–6973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811818106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng H, Kumar K. Antimicrobial activity and protease stability of peptides containing fluorinated amino acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15615–15622. doi: 10.1021/ja075373f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng H, Krishnaji ST, Beinborn M, Kumar K. Influence of selective fluorination on the biological activity and proteolytic stability of glucagon-like peptide-1. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7303–7307. doi: 10.1021/jm8008579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]