Abstract

NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) provides long-range distance constraints (∼15–25 Å) that can be critical to determining overall protein topology, especially where long-range NOE information is unavailable such as in the case of larger proteins that require deuteration. However, several challenges currently limit the use of NMR PRE for α-helical membrane proteins. One challenge is the nonspecific association of the nitroxide spin label to the protein-detergent complex that can result in spurious PRE derived distance restraints. The effect of the nitroxide spin label contaminant is evaluated and quantified and a robust method for the removal of the contaminant is provided to advance the application of PRE restraints to membrane protein NMR structure determination.

Keywords: paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, membrane proteins, paramagnetic probes, site directed spin labeling, nitroxide spin label

Introduction

NMR structures of polytopic α-helical membrane proteins are difficult to determine due to challenges in expression, yields, and selection of surfactants that extract, solubilize, and stabilize protein structure and function.1–4 For solution NMR studies, the resulting protein-detergent complex is often large requiring TROSY pulse sequences and deuteration to improve spectral resolution.5–7 However, deuteration results in the loss of important proton information that limits the number of structural restraints obtained from NOESY methods. Therefore, additional restraints are required and are typically obtained from specific methyl incorporated NOE restraints,8 residual dipolar couplings,9 and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments.10, 11

PRE restraints have been increasingly used for the structure determination of biomolecules due to the long-range distance information (∼15–25 Å) obtained.10,12–14 However, several challenges currently limit PRE derived restraints to low-resolution applications for α-helical membrane proteins.11,15–17 The r−6 distance dependence of the relaxation enhancement strongly biases a calculated distance restraint to the shortest distance in an ensemble. The distance measurement is further complicated by the conformational sampling of the spin label, which has been quantified on soluble α-helical proteins18–21 and is currently being investigated on α-helical22 and β-barrel23 membrane proteins. Additional practical challenges arise from underlabeling protein, failure to remove excess spin label, and nonspecific association of the spin label to the protein; each of which can severely compromise the quality of PRE data and lead to erroneous distances. For proteins in or associated with detergent micelles, these challenges have been shown by reductions in labeling efficiencies due to accessibility of sites within the micelle24 and the nonspecific association of unreacted spin label with the protein-detergent complex.12, 22, 25, 26

Spin label contamination (which here refers to unreacted spin label not removed using typical methods such as desalting or gel-filtration columns) has been reported in EPR and NMR investigations of proteins in or associated with detergent micelles12, 22, 25, 26 even after several purification steps.22, 26 For NMR studies, the spin label contaminant results in the enhanced relaxation of protons not related to the site-specifically incorporated nitroxide resulting in spurious PRE derived distance restraints. For a 30 kDa protein detergent complex [with a τc of 13 ns and a R2 (diamagnetic) of 20 s−1 at 800 MHz], the presence of spin label contaminant could reduce intensities by 50% resulting in the specious restraints of ∼20 Å. In this work, the effect of spin label contaminant is evaluated and quantified on the model system TM0026 from Thermotoga maritima, which contains two transmembrane α-helices27 and no native cysteine residues. A robust method for removal of the most common spin label, (1-oxy-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate spin label (MTSSL; side chain designated as R1), contaminant is provided to advance the application of PRE restraints to membrane protein NMR structure determination.

Results and Discussion

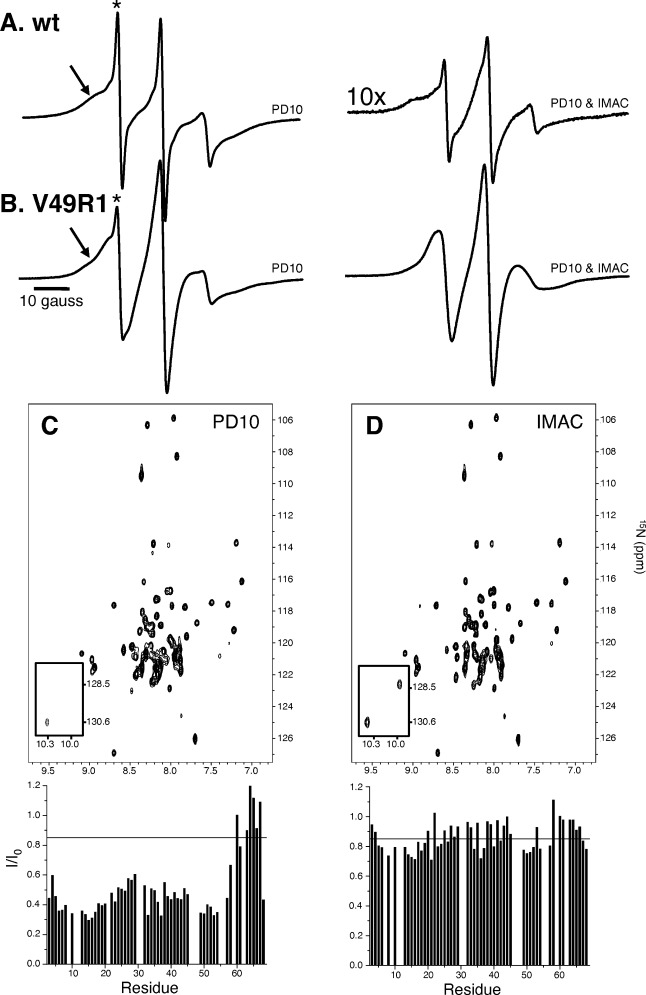

To investigate the source of the spin label containment, the EPR spectra of wild-type (wt) TM0026 were recorded [Fig. 1(A)]. TM0026 was incubated overnight with nitroxide spin label at a molar ratio of 1:15 (protein:spin label) after which excess spin label was removed with a PD-10 desalting column. The EPR spectrum reveals a substantial amount of unreacted spin label contaminant [Fig. 1(A)] and has two distinct spectral populations. One population is characterized by the three equally spaced, sharp lines indicative of a spin label with relatively unrestricted and fast (< 1 ns) motion (indicated with an asterisk in Fig. 1). The second population has resolved hyperfine-splitting characteristic of a spin label with relatively restricted motion (≍ 20 ns) that is typically observed at protein tertiary contact sites (indicated with an arrow in Fig. 1).21, 28 The use of a desalting PD-10 column effectively removes the bulk of unreacted spin label; however, spin label associated with the protein-detergent complex is not removed. After 3 days of incubation at room temperature and passing through a Co2+ IMAC column, the spin label contaminant is reduced eight fold [Fig. 1(A)]. In the presence of a free cysteine introduced at site V49, this protocol removes any visage of spin label contaminant [Fig. 1(B)].

Figure 1.

EPR spectra of wt TM0026 (A) and V49R1 (B) at various stages of spin label removal. The use of a desalting PD-10 column (left panel) effectively removes the bulk of unreacted spin label; however, it is ineffective at removing unreacted spin label associated with the protein micelle complex. After 3 days of incubation at room temperature and passing through a Co2+ IMAC column (right panel), the contaminate spin label concentration is reduced eight fold. C and D: 15N, 1H-TROSY-HSQC spectra of wt TM0026 after attempts to remove excess MTSSL and corresponding plots of intensity ratios versus residue are shown: (C) after a PD-10 desalting column was used to remove excess spin label (MTSSL) and (D) after 3 days at room temperature and a Co2+ IMAC column to remove excess spin label (intensities plotted below are normalized to TM0026 without spin label added). A black line is drawn at an intensity ratio of 0.85, a commonly used upper limit for quantitative distance restraints.

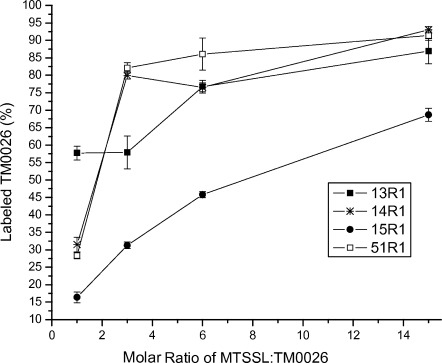

One potential method to mitigate concern with unreacted excess spin label is to label at stoichiometric amounts. However, the potential risk is under-labeling the protein of interest resulting in spurious distance restraints from a heterogeneous sample of labeled and unlabeled protein (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The labeling efficiency varies between sites on the protein and to some extent correlates with the accessibility of the sulfhydryl. Typically, excess MTSSL is needed to drive the reaction to completion (Fig. 2). Even at a molar ratio of 1:6 (protein:spin label), labeling overnight, the labeling efficiency is highly variable between different sites, with more occluded sites labeling less efficiently than exposed sites consistent with previous observations.24 The high labeling efficiency required for PRE measurements cannot be achieved unless high concentrations (relative to protein) of spin label are used (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Labeling efficiency quantified using MALDI TOF mass spectrometry for four sites on TM0026. All four sites are on transmembrane α-helices as assessed by the predicted topology and NOE crosspeaks between the amide proton and the alkyl chain of the detergent (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In addition, the EPR spectra of V15R1 and A13R1 indicate the nitroxide has restricted motion, which suggests these residues are tertiary contact sites and more occluded compared to L14R1 and L51R1. (The labeling efficiency is <100%; however, disulfide bonds fragmentation during the MALDI TOF measurement was previously observed37 and could account for the ∼10% of under-labeling observed).

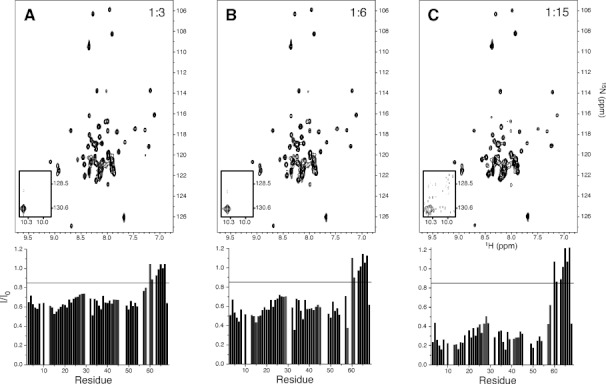

The effect of excess spin label on the intensity ratios observed in a 15N, 1H-TROSY-HSQC spectrum of wt TM0026 is illustrated in Figure 3. Significant line broadening is observed with a threefold excess of spin label and increases with increasing spin label concentration. The greatest broadening is observed in the center of the two helices, which, based on NOEs with the detergent micelle alkyl chain protons, are embedded in the micelle (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Note that, in the presences of spin label, longitudinal relaxation is enhanced in the mobile C-terminus, which biases the normalized intensities—the effect of modulated amplitude by longitudinal relaxation on calculated distances can be avoided by the use of a two time point measurement experiment.29 Intensity ratios that fall below 0.85 in the absence of a selectively reacted cysteine are particularly problematic since distance restraints from intensity ratios between 0.15 and 0.85 are considered most reliable.10, 12, 30, 31

Figure 3.

The 15N, 1H-TROSY-HSQC spectra of wt TM0026 with varying levels of MTSSL titrated into solution and corresponding intensity ratios versus residue plotted below: (A) 1:3 molar ratio of wt TM0026:MTSSL; (B) 1:6 molar ratio of wt TM0026:MTSSL; (C) 1:15 molar ratio of wt TM0026:MTSSL. The two tryptophan indole peaks are shown as an inset. A black line is drawn at an intensity ratio of 0.85, a commonly used upper limit for quantitative distance restraints.

After removal of excess spin label with a desalting PD-10 column, a three day incubation and second PD-10 column, the remaining spin label contaminant results in significant line broadening in the 15N, 1H-TROSY-HSQC spectrum of wt TM0026 [Fig. 1(C); corresponding EPR spectrum in Supporting Information Fig. S3]. Similar to the effects observed with excess spin label, the intensity ratios are lowest in center of the two helices. After incubation at room temperature for 3 days and passing through a Co2+ IMAC column, the intensity ratios return closer to 1 (for the structured micelle embedded region of the protein and the C-terminal residues) and far fewer ratios are below 0.85 [Fig. 1(D); corresponding EPR spectrum in Fig. 1(A), right panel)]. The time required for incubation suggests an activation barrier between the spin label in the protein detergent complex and in aqueous and/or empty micellar solution likely due to an unfavorable solvation of the spin label in the aqueous phase versus in the amphipathic micelle.32, 33 Thus, the spin label contaminant seems to be kinetically trapped in the protein-detergent complex and over time equilibrates with the empty micelles and bulk solution. Once equilibrated, the separation of the empty micelles from the protein-detergent complex is required.

In conclusion, the use of PRE distance restraints in α-helical membrane protein structure determination can be an invaluable tool17; however, there are still several challenges that need to be addressed before this method can be employed with maximal precision. One challenge that we addressed here is the presence of unreacted, nonspecifically associated spin label contaminant that seems to be prevalent and complicates the interpretation of relaxation data. To circumvent this challenge, a strategy of separation such as affinity chromatography is suggested for PRE and EPR investigations of membrane proteins in detergent micelles. Additionally, the need for quantifying labeling efficiencies for reliable PRE-derived distances is emphasized and MALDI-TOF and/or EPR intensity integration is recommend determining the extent of labeling.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of TM0026 wt and mutants

Previously published protocols34, 35 were followed. Briefly, all cysteine mutations were introduced using PIPE mutagenesis.36 Mutants were confirmed by sequencing the entire gene (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ). The gene for TM0026 with an N-terminal tag (MGSDKIHHHHHH) was cloned into pET25b (between NdeI and BamHI restriction sites) and transformed into BL21 (DE3) RIL cells (Stratagene; Santa Clara, CA). Cells were grown at 310 K to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (Research Products International; Mt. Prospect, IL) for 4 h at 310 K. The cells were resuspended and lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (lysis buffer). After lysing the cells, the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000g for 60 min. The supernatant (cell membranes) was supplemented with 10 mMn-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DM; Anatrace, Maumee, OH) for 3 h at room temperature. Afterward, the suspension was passed through a Co2+ immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) column equilibrated with 10 column volumes (CV) of lysis buffer with 5 mM DM. The column was washed with 15 CV of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP, and 5 mM DM and eluted in 10 CV of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 5 mMn-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM; Anatrace, Maumee, OH), 15 mMn- dodecylphosphocholine (FC-10; Anatrace, Maumee, OH), and 600 mM imidazole.

Spin labeling

The Co2+ IMAC eluted fraction was concentrated and passed through a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) to remove TCEP and imidazole and to exchange the buffer to 20 mM Phosphate buffer (pH 6.2), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DDM, and 15 mM FC-10 (NMR buffer) for spin labeling. The instructions for the PD-10 column was adjusted such that the sample volume loaded was 200 μL and, after the 200 μL was loaded onto the column, 3.5 mL of NMR buffer was added to the column and collected. To the 3.5 mL of elution, the appropriate volume of spin label (100 mM stock in acetonitrile) was added immediately. Each spin labeling reaction was incubated overnight.

To remove excess MTSSL, the overnight-incubated sample was passed through a PD-10 column (loaded <200 μL and eluted into 3.5 mL of NMR buffer). When indicated, subsequent Co2+ IMAC or PD-10 column purifications (Fig. 1) were performed as previously described using an elution of NMR buffer with or without 600 mM imidazole, respectively. During both labeling overnight and 3 day incubation periods, the protein concentration was ∼10 μM. Samples were then concentrated and dialyzed in a 3.5 kDa MWCO dialysis tube (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA) against 4 L of NMR buffer without DDM or FC-10 for two hours three times to remove imidazole. The dialysis step had no effect on unreacted spin label concentration in solution as observed by NMR and EPR.

EPR spectroscopy

The room temperature X-band EPR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker EMX spectrometer with an ER4123D dielectric resonator (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). Protein samples of 5 μL (≍ 100 μM) were loaded into Pyrex capillaries (0.60 mm id × 0.84 mm od; Fiber Optic Center, New Bedford, MA).

Quantification of labeling efficiency with mass spectrometry

Cysteine mutants of TM0026 were incubated at room temperature overnight with increasing concentrations of MTSSL. The reacted samples were then diluted 200 fold in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) and plated 1 part diluted protein solution to 1 part sinapinic acid to form 2 μL of the final matrix for the matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) experiment with a Bruker Microflex mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics; Billerica, MA). The relative abundances of each species, unlabeled and labeled, were quantified by comparing peak intensities. The result of the spin labeling reaction changed the molecular weight of the protein by ∼180 Da (e.g., 9670 vs. 9490 Da for site A13).

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were collected on Bruker AVANCE spectrometers operating at proton frequencies of 600 MHz and 800 MHz equipped with Bruker 5 mm TXI cryoprobes and recorded at 313 K. Spectra were processed with NMRPipe37 and assigned using CARA.38 For the sequence-specific resonance assignments of the polypeptide backbone atoms, the following TROSY experiments were recorded: 2D 15N, 1H-HSQC, 3D HNCACB, 3D HN(CO)CA, 3D HN(COCA)CB, 3D HN(CA)CO, and 3D HNCO.39, 40 The resonance backbone assignments obtained were complete except for the N-terminal affinity tag and residues I9, S11, W12, L48, E55, and K56-R59. Peak heights were estimated through parabolic interpolation using NMRPipe37 and normalized to the average of nine (∼15%) unperturbed resonances. Intensity ratios, I/I0, were calculated for each spectrum (I) with respect to TM0026 in the absence of spin label (I0).

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Nietlispach D, Gautier A. Solution NMR studies of polytopic alpha-helical membrane proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patching SG. NMR structures of polytopic integral membrane proteins. Mol Membr Biol. 2011;28:370–397. doi: 10.3109/09687688.2011.603100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders CR, Sonnichsen F. Solution NMR of membrane proteins: practice and challenges. Magn Reson Chem. 2006;44:S24–40. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamm LK, Liang B. NMR of membrane proteins in solution. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2006;48:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez C, Wider G. TROSY in NMR studies of the structure and function of large biological macromolecules. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster MP, McElroy CA, Amero CD. Solution NMR of large molecules and assemblies. Biochemistry. 2007;46:331–340. doi: 10.1021/bi0621314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wider G. NMR techniques used with very large biological macromolecules in solution. Methods Enzymol. 2005;394:382–398. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)94015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tugarinov V, Kay LE. Methyl groups as probes of structure and dynamics in NMR studies of high-molecular-weight proteins. Chem Biochem. 2005;6:1567–1577. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cierpicki T, Liang B, Tamm LK, Bushweller JH. Increasing the accuracy of solution NMR structures of membrane proteins by application of residual dipolar couplings. High-resolution structure of outer membrane protein a. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6947–6951. doi: 10.1021/ja0608343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang B, Bushweller JH, Tamm LK. Site-directed parallel spin-labeling and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in structure determination of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4389–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja0574825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi L, Traaseth NJ, Verardi R, Gustavsson M, Gao J, Veglia G. Paramagnetic-based NMR restraints lift residual dipolar coupling degeneracy in multidomain detergent-solubilized membrane proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2232–2241. doi: 10.1021/ja109080t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battiste JL, Wagner G. Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5355–5365. doi: 10.1021/bi000060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaponenko V, Howarth JW, Columbus L, Gasmi-Seabrook G, Yuan J, Hubbell WL, Rosevear PR. Protein global fold determination using site-directed spin and isotope labeling. Protein Sci. 2000;9:302–309. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos A, Varani G. A new method to detect long-range protein-RNA contacts: NMR detection of electron-proton relaxation induced by nitroxide spin-labeled RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10992–10993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berardi MJ, Shih WM, Harrison SC, Chou JJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature. 2011;476:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Ji F, Olman V, Mobley CK, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Bushweller JH, Prestegard JH, Xu Y. Optimal mutation sites for PRE data collection and membrane protein structure prediction. Structure. 2011;19:484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, Cierpicki T, Jimenez RH, Lukasik SM, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS, Kadokura H, Beckwith J, Bushweller JH. NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: functional insights into dsbb-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Columbus L, Kalai T, Jeko J, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Molecular motion of spin labeled side chains in alpha-helices: analysis by variation of side chain structure. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3828–3846. doi: 10.1021/bi002645h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleissner MR, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Structural origin of weakly ordered nitroxide motion in spin-labeled proteins. Protein Sci. 2009;18:893–908. doi: 10.1002/pro.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langen R, Oh KJ, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Crystal structures of spin labeled T4 lysozyme mutants: Implications for the interpretation of EPR spectra in terms of structure. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8396–8405. doi: 10.1021/bi000604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHaourab HS, Lietzow MA, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Motion of spin-labeled side chains in T4 lysozyme. Correlation with protein structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7692–7704. doi: 10.1021/bi960482k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroncke BM, Horanyi PS, Columbus L. Structural origins of nitroxide side chain dynamics on membrane protein alpha-helical sites. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10045–10060. doi: 10.1021/bi101148w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freed DM, Khan AK, Horanyi PS, Cafiso DS. Molecular origin of electron paramagnetic resonance line shapes on beta-barrel membrane proteins: the local solvation environment modulates spin-label configuration. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8792–8803. doi: 10.1021/bi200971x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly BL, Gross A. Potassium channel gating observed with site-directed mass tagging. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nsb908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Do Cao MA, Crouzy S, Kim M, Becchi M, Cafiso DS, Di Pietro A, Jault JM. Probing the conformation of the resting state of a bacterial multidrug ABC transporter, BmrA, by a site-directed spin labeling approach. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1507–1520. doi: 10.1002/pro.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross A, Columbus L, Hideg K, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL. Structure of the KcsA potassium channel from Streptomyces lividans: A site-directed spin labeling study of the second transmembrane segment. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10324–10335. doi: 10.1021/bi990856k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Columbus L, Lipfert J, Jambunathan K, Fox DA, Sim AY, Doniach S, Lesley SA. Mixing and matching detergents for membrane protein NMR structure determination. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7320–7326. doi: 10.1021/ja808776j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Z, Cascio D, Hideg K, Kalai T, Hubbell WL. Structural determinants of nitroxide motion in spin-labeled proteins: tertiary contact and solvent-inaccessible sites in helix g of T4 lysozyme. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1069–1086. doi: 10.1110/ps.062739107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwahara J, Tang C, Clore GM. Practical aspects of (1)H transverse paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements on macromolecules. J Magn Reson. 2007;184:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindfors HE, de Koning PE, Drijfhout JW, Venezia B, Ubbink M. Mobility of TOAC spin-labelled peptides binding to the Src SH3 domain studied by paramagnetic NMR. J Biomol NMR. 2008;41:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9248-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page RC, Lee S, Moore JD, Opella SJ, Cross TA. Backbone structure of a small helical integral membrane protein: a unique structural characterization. Protein Sci. 2009;18:134–146. doi: 10.1002/pro.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu YG, Thorgeirsson TE, Shin YK. Topology of an amphiphilic mitochondrial signal sequence in the membrane-inserted state: a spin labeling study. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14221–14226. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sammalkorpi M, Lazaridis T. Modeling a spin-labeled fusion peptide in a membrane: implications for the interpretation of EPR experiments. Biophys J. 2007;92:10–22. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Columbus L, Lipfert J, Jambunathan K, Fox DA, Sim AY, Doniach S, Lesley SA. Mixing and matching detergents for membrane protein NMR structure determination. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7320–7326. doi: 10.1021/ja808776j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Columbus L, Lipfert J, Klock H, Millett I, Doniach S, Lesley SA. Expression, purification, and characterization of Thermotoga maritima membrane proteins for structure determination. Protein Sci. 2006;15:961–975. doi: 10.1110/ps.051874706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klock HE, Lesley SA. The polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller RLJ. Optimizing the process of nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum analysis and computer aided resonance assignment. Natural Sciences. Zurich: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bax A, Grzesiek S. Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.