Abstract

In this report, 19F spin incorporation in a specific site of a specific membrane protein in E. coli was accomplished via trifluoromethyl-phenylalanine (19F-tfmF). Site-specific 19F chemical shifts and longitudinal relaxation times of diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK), an E. coli membrane protein, were measured in its native membrane using in situ magic angle spinning (MAS) solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Comparing with solution NMR data of the purified DAGK in detergent micelles, the in situ MAS-NMR data illustrated that 19F chemical shift values of residues at different membrane protein locations were influenced by interactions between membrane proteins and their surrounding lipid or lipid mimic environments, while 19F side chain longitudinal relaxation values were probably affected by different interactions of DAGK with planar lipid bilayer versus globular detergent micelles.

Keywords: in situ solid state NMR, membrane proteins, native membrane, detergent micelles, chemical shift, longitudinal relaxation, protein specific and site-specific isotope labeling

Introduction

The functional diversity of membrane proteins is determined not only by membrane proteins themselves, but also by their interactions with membranes. Native cellular membranes host various proteins, together with lipids in a variety of compositions in both leaflets.1 These heterogeneous membrane environment is known to influence conformational plasticity of membrane proteins, which is essential for their functions under native conditions.2 Studies on the structure and function of membrane proteins in their native membrane environment are therefore necessary to achieve a good understanding of their molecular mechanisms. To date, most methodologies used in membrane protein structure studies require purified proteins in either synthetic lipid bilayers or detergent micelles.3 In these circumstances, membrane proteins are in an environment with different electrical, chemical, and mechanical properties from their native cellular membranes. Only very few reports have been made of structural studies of membrane proteins in their native membranes.4 Recently, several solid state NMR analysis of bacteria cells with either fully 13C labeling5 or amino acid-specific (13C or 15N) labeling6 on over-expressed membrane proteins were reported. But none of them are aiming at protein-specific and site-specific labeling. Here, we present a new in situ method with protein- and site-specific isotope labeling to study the conformation and dynamics of membrane proteins in their native environment without further purification, using magic angle spinning (MAS) solid state nuclear magnetic resonance. An E. Coli membrane protein, diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK), was applied to demonstrate the feasibility of this new method. DAGK is a homotrimetric membrane protein composed of 121 residue subunits, each of which has three transmembrane helices.7 Here, solution NMR data of purified DAGK in detergent micelles were also acquired. A comparison of the solid state and solution NMR data indicated importance of environmental influences on chemical shift and relaxation data of membrane protein residues at different locations.

To implement in situ solid state NMR studies of membrane proteins in their native environment, a protein-specific isotope labeling protocol is required. Recently, an unnatural amino acid, trifluoromethyl-phenylalanine (19F-tfmF), was introduced to a protein for site-specific side chain 19F chemical shift and relaxation rates measurements using solution NMR.8, 9 In this method, site-specific labeling was facilitated by an orthogonal amber tRNA/tRNA synthetase (tRNA/RS) pair and tfmF was specifically incorporated into a protein at the amber nonsense codon (TAG) in the protein's coding DNA sequence.10 Protein-specific 19F-tfmF incorporation could therefore be accomplished if the amber nonsense codon (TAG) mutation was prepared only in DAGK, while other proteins would not be 19F-labeled, due to absence of either background 19F signals or 19F spin transferring mechanisms in E. coli.

Results and Discussion

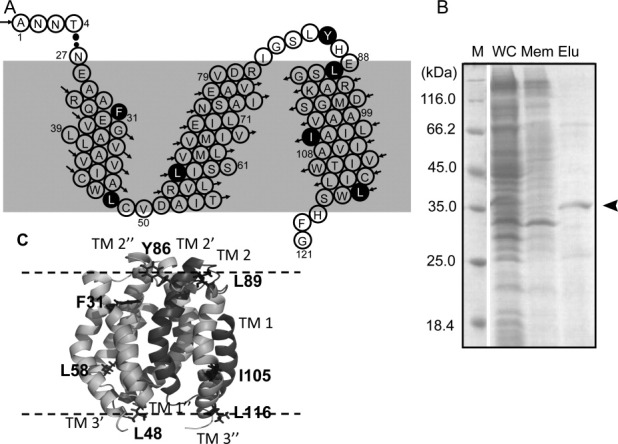

DAGK proteins with 19F-tfmF incorporation at seven different sites [Fig. 1(A,C): F31, L48, L58, Y86, L89, I105, and L116, which were known to cause minor perturbations to DAGK folding and activities7] were over-expressed in E. coli. The maximum tfmF-DAGK expression yield was quantified to less than 1.0 mg from 1 L culture [Fig. 1(B)]. This expression yield of tfmF-DAGK might preclude possibilities of protein aggregation in E. coli membrane.

Figure 1.

A: Primary sequence of full length DAGK1-121 with three transmembrane helices in each subunit. Residues with black backgrounds were mutated to tfmF for 19F-NMR analysis. B: SDS-PAGE results of the purified DAGK protein (WC, whole cell; Mem, membrane fraction after ultracentrifugation; Elu, elution fraction). C: Cartoon representation of trimeric structure of DAGK with mutation sites shown with side chains. The cartoon was built following PDB entry 2KDC.

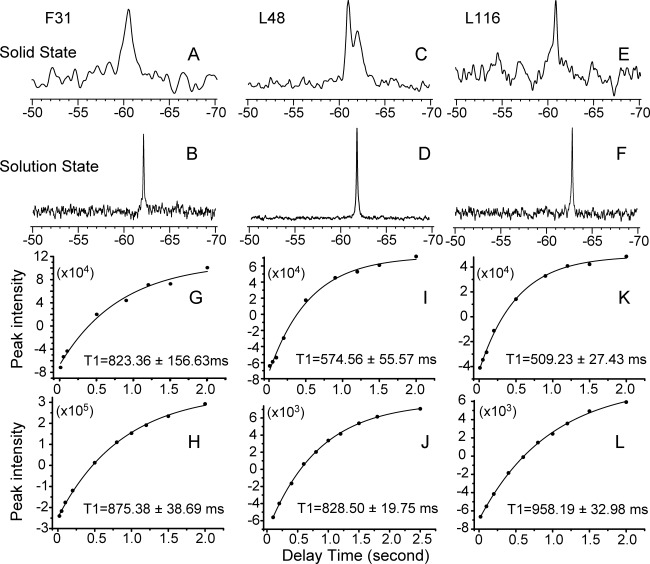

One dimensional 19F solid state and solution NMR spectra are shown for F31-tfmF, L48-tfmF, and L116-tfmF DAGKs in Figure 2(A–F). Since 19F-tfmF was site-specifically introduced to DAGK, a single 19F resonance was observed in the solution NMR spectra [Fig. 2(B,D,F)], indicating a homogenous sample in the DAGK/DPC micelles.9 A single 19F resonance was also observed for F31tfmF-DAGK and L116-tfmF-DAGK in native E. coli membrane [Fig. 2(A,E)] despite of much larger peak line width in solid state NMR spectra. This strongly indicates that it is possible to achieve protein-specific and site-specific 19F labeling via the unnatural amino acid method, and that over-expressed DAGK adopts a homogenous conformation in its native membrane environment. However, it is difficult to obtain a single 19F solid state resonance for intact E. coli cells with over-expressed tfmF-DAGK, due to difficulties in the sample treatments, and the presence of 19F-containing tfmF compound, tfmF-tRNA and other related metabolic intermediates (data not shown). Two 19F solid state NMR resonances were observed for L48-tfmF DAGK; which was possibly due to presence of two conformations around the 48th site, in a loop region connecting TMH1 and TMH2 of DAGK [Fig. 1(A,C)].

Figure 2.

In situ magic angle spinning solid state NMR 19F chemical shifts (A, C, E) and longitudinal relaxation T1 values (G, I, K) were obtained for the DAGK protein in its native E. coli membrane without protein purification. Solution NMR 19F chemical shifts (B, D, F) and longitudinal relaxation T1 values (H, J, L) were obtained for samples of purified DAGK in DPC micelles. Three 19F-tfmF site-specifically labeled DAGK proteins were presented: F31-tfmF (A, B, G, H); L48-tfmF (C, D, I, J) and L116-tfmF (E, F, K. L).

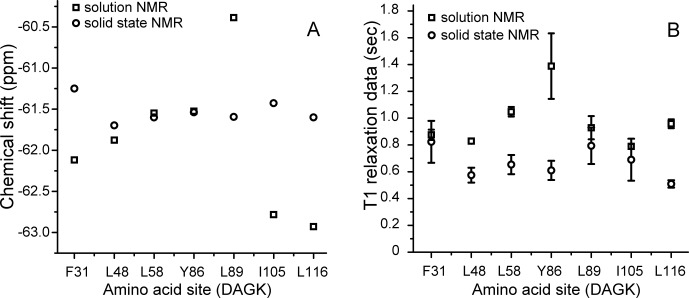

The solid-state and solution NMR 19F chemical shifts for DAGK with tfmF incorporation at seven different sites were summarized in Figure 3(A). Since the 19F chemical shift is very sensitive to the protein's local environment,11 different 19F isotropic chemical shift values of solid-state versus solution NMR provide evidence for different lipid interactions of DAGK residues at different sites. Here, only minor differences in the 19F chemical shift values of solid state versus solution NMR for sites L48-tfmF, L58-tfmF, and Y86-tfmF were shown, while significant 19F chemical shift differences were observed for sites F31-tfmF, L89-tfmF, I105-tfmF, and L116-tfmF. From the trimeric solution NMR DAGK structure in DPC micelles7, F31, L89, I105, and L116 are located in the first or third helix of DAGK. These four residues are on the external surface of the trimeric protein, having direct contact with surrounding lipid or detergent molecules [Fig. 1(C)]. Therefore, the large chemical shift differences in the four sites are probably due to influences from diverse and heterogeneous lipid composition in native bacterial membrane versus detergent micelles containing pure artificial compounds. The three sites L48, L58, and Y86 are located in the internal core of trimeric DAGK or interfacial region between each DAGK monomer. The consequent minor 19F chemical shift differences in these three sites are probably due to presence of only inter-residue interaction, and absence of protein–lipid contacts.

Figure 3.

Different 19F chemical shifts (A) and longitudinal relaxation T1 values (B) of DAGK proteins in their native E. coli membranes using in situ solid state NMR (o) versus purified DAGK proteins in DPC micelles using solution NMR (□), with 19F-spin incorporation at seven different sites.

Using solid state NMR, the longitudinal relaxation time T1 (or relaxation rate R1) measurements were reported in internal mobility analysis of solid proteins.12 The protein- and site-specific 19F labeling, together with the success in obtaining the 19F solid state NMR resonance of DAGK in its native membranes, provided the basis for further site-specific dynamics analysis. The side chain 19F-tfmF longitudinal relaxation time T1 was measured at different DAGK sites. Conventional inverse recovery pulse sequence was applied in both solid state and solution NMR, and curve fits were shown in Figure 2(G–L).

It is know that the T1 relaxation time of methyl spins (–CH3 or –CF3 in tfmF) is dominated by methyl group rotation, both in solids and liquids.13 For the same globular proteins, a strong correlation was found between the solid and solution state methyl 13C and 1H T1 relaxation data, due to their structure conservation.14 Summaries of the T1 relaxation data for the 19F side chain at different DAGK sites, in either native membrane or detergent micelles, are shown in Figure 3(B). Similar T1 values were observed at three sites F31, L89, and I105, which are deeply buried in hydrophobic region [Fig. 1(C)].7 Then, side chain rotational motion of these three sites might not be affected by differences between lipids and detergent micelles. Different T1 values (with differences larger than the error bars) were observed at the other four sites: L48, L58, Y86, and L116, which are located in lipid-aqueous interfacial region.7 Several reports have mentioned that detergent micelles might bring surface curvature distortion15 and expandable hydrophobic dimension16 to membrane proteins. Rotational motions of CF3- group in lipid-aqueous interfacial region might be strongly influenced by differences between globular shape detergent micelles and planar lipid bilayers of native membrane. Of course, further structural characterization and comparisons of a membrane protein in its native membrane versus detergent micelles are required to provide direct evidences.

In summary, our studies have demonstrated a new method for the in situ solid state NMR studies of membrane proteins in their native environment. This approach offers an opportunity to expand the field of in situ membrane proteins structural and dynamic studies in native membranes, which can provide native conditions for the membrane proteins, including native lipid compositions and functional partners. Investigation of the effects of membrane heterogeneity, and protein–protein interaction to membrane proteins' structure and function would be more feasible in their native lipid environments rather than using detergent micelles or synthetic lipid bilayers.

Materials and Methods

Membrane fraction collection and 19F MAS solid state NMR

DAGK over-expression with 19F-tfmF incorporated at seven different sites (Phe31, leu48, Leu58, Tyr86, Leu89, Ile105, and Leu116) were achieved similarly as previously described.8, 9E. coli cells expressing tfmF-DAGK were harvested using centrifugation with 5000g, at 4°C. The cell paste was suspended in 10 mL buffer [70 mM Tris-HCl and 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0] per gram of wet cells. The cell suspension in lysis buffer was probe-sonicated (VC500, Sonics and Materials, Danbury, CT) for 5 min on ice. Lysozyme (to 1.0 mg/mL), DNase (to 0.02 mg/mL), RNase (to 0.02 mg/mL) and Magnesium Acetate (to 5.0 mM) were added and the lysate was rotated at 4°C for 2 h. The lysate was centrifuged at 4°C and 40,000g for 20 min and the pellet fraction containing inclusion bodies, unbroken cells, and insoluble cell debris was discarded. The supernatant was ultra- centrifuged at 4°C and 100,000g, 2 h. The pellet containing bacteria membrane and integral membrane proteins was then washed using NMR buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 6.5). Final pellet fraction was carefully transferred to a 2.5 mm solid state NMR spin rotor.

All solid state NMR measurements were carried out on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz NMR spectrometer at 298 K, equipped with a 2.5 mm two channel broad band MAS probe. The sample spinning rate was 20 kHz ± 3 Hz controlled by a Bruker pneumatic MAS unit. One dimensional 19F spectra was acquired with a single pulse (with 90° pulse width of 3.3 μs, spectral width of 200 ppm) on 19F channel and a TPPI proton decoupling scheme in 1H channel. A 19F free induction decays were acquired with 512 scans and acquisition delay of 10 s. A standard inverse recovery Bruker pulse sequence with 1H continues wave decoupling was applied to measure T1 longitudinal relaxation times, with 9 delay intervals (10, 50, 100, 200, 500, 900, 1200, 1500, and 2000 ms). The free induction decays (FIDs) were apodized with an exponential window function (50 Hz), zero-filled to 1024 points before Fourier transform using Bruker Topspin 2.0 software. 19F chemical shift was referenced to an external standard, trifluoro-acetic acid (TFA) at −75.39 ppm.

Solution NMR sample preparation and 19F spectrum collection

Over-expressed DAGK protein was purified into DPC micelles for solution NMR samples as described previously.7 Samples of 0.2 mM tfmF-DAGK/DPC were prepared in 500 μL of aqueous buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 6.5) containing 10% D2O. All 19F NMR spectra were acquired in a Bruker Avance 400 MHz solution NMR spectrometer equipped with a double channel broad band HX probe, at 298 K, with 90° pulse width of 16.8 μs, spectral width of 50 ppm, 256 FID accumulations in every 5-s acquisition delay. Side chain 19F T1 relaxation data were collected with 10 delay intervals (20, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1200, 1500, and 2000 ms) using a standard inverse-recovery pulse sequence with 1H decoupling. 19F solution NMR data were processed with an exponential window function (10 Hz) using TopSpin 2.0. 19F chemical shift was referenced to (TFA) at −75.39 ppm.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful for the kind courtesy of provision of plasmid pDule-tfmF by Dr. R.A. Mehl, Department of Chemistry, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, PA.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DAGK

diacylglycerol kinase

- DPC

dodecyl phosphocholine

- MAS

magic angle spinning

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- tfmF

p-trifluoromethyl-phenylalanine.

References

- 1.Engelman DM. Membranes are more mosaic than fluid. Nature. 2005;438:578–580. doi: 10.1038/nature04394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross TA, Sharma M, Yi M, Zhou HX. Influence of solubilizing environments on membrane protein structures. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bill RM, Henderson PJ, Iwata S, Kunji ER, Michel H, Neutze R, Newstead S, Poolman B, Tate CG, Vogel H. Overcoming barriers to membrane protein structure determination. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:335–340. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varga K, Aslimovska L, Watts A. Advances towards resonance assignments for uniformly—13C, 15N enriched bacteriorhodopsin at 18.8 T in purple membranes. J Biomol NMR. 2008;41:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu R, Wang X, Li C, Santiago-Miranda AN, Pielak GJ, Tian F. In situ structural characterization of a recombinant protein in native Escherichia coli membranes with solid-state magic-angle-spinning NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12370–12373. doi: 10.1021/ja204062v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel EP, Curtis-Fisk J, Young KM, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of human immunodeficiency virus gp41 protein that includes the fusion peptide: NMR detection of recombinant Fgp41 in inclusion bodies in whole bacterial cells and structural characterization of purified and membrane-associated Fgp41. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10013–10026. doi: 10.1021/bi201292e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Horn WD, Kim HJ, Ellis CD, Hadziselimovic A, Sulistijo ES, Karra MD, Tian C, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Solution nuclear magnetic resonance structure of membrane-integral diacylglycerol kinase. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi P, Xi Z, Wang H, Shi C, Xiong Y, Tian C. Site-specific protein backbone and side-chain NMR chemical shift and relaxation analysis of human vinexin SH3 domain using a genetically encoded 15N/19F-labeled unnatural amino acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi P, Wang H, Xi Z, Shi C, Xiong Y, Tian C. Site-specific (1)F NMR chemical shift and side chain relaxation analysis of a membrane protein labeled with an unnatural amino acid. Protein Sci. 2010;20:224–228. doi: 10.1002/pro.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson JC, Hammill JT, Mehl RA. Site-specific incorporation of a (19)F-amino acid into proteins as an NMR probe for characterizing protein structure and reactivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1160–1166. doi: 10.1021/ja064661t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frieden C, Hoeltzli SD, Bann JG. The preparation of 19F-labeled proteins for NMR studies. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:400–415. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chevelkov V, Diehl A, Reif B. Measurement of 15N-T1 relaxation rates in a perdeuterated protein by magic angle spinning solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:052316. doi: 10.1063/1.2819311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millet O, Mittermaier A, Baker D, Kay LE. The effects of mutations on motions of side-chains in protein L studied by 2H NMR dynamics and scalar couplings. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal V, Xue Y, Reif B, Skrynnikov NR. Protein side-chain dynamics as observed by solution- and solid-state NMR spectroscopy: a similarity revealed. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16611–16621. doi: 10.1021/ja804275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou JJ, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Micelle-induced curvature in a water-insoluble HIV-1 Env peptide revealed by NMR dipolar coupling measurement in stretched polyacrylamide gel. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2450–2451. doi: 10.1021/ja017875d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Detergents as tools in membrane biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32403–32406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]