Abstract

Alfred Adler attempted to understand how family affects youth outcomes by considering the order of when a child enters a family (Adler, 1964). Adler’s theory posits that birth order formation impacts individuals. We tested Adler’s birth order theory using data from a cross-sectional survey of 946 Chilean youths. We examined how birth order and gender are associated with drug use and educational outcomes using three different birth order research models including: (1) Expedient Research, (2) Adler’s birth order position, and (3) Family Size theoretical models. Analyses were conducted with structural equation modeling (SEM). We conclude that birth order has an important relationship with substance use outcomes for youth but has differing effects for educational achievement across both birth order status and gender.

Introduction

Studies indicate that family dynamics play an important role with regard to drug use and educational outcomes for youth (Allison, 1992; Bachman et. al., 2008; Bergen, Martin, Roeger, & Allison, 2005; Chilcoat, Dishion, & Anthony, 1995; Hill, Hawkins, Catalano, Abbott, & Guo, 2005; Yu, 2003). One theory developed by Alfred Adler attempts to understand how family matters by considering the order of when a child enters a family (Adler, 1964). Adler’s theory posits that different positions in a family birth order may be correlated both positive and negative life outcomes. For example, researchers have noted that first-born children have an increased susceptibility to both drug use as well as positive educational outcomes (Laird & Shelton, 2006). Though limited in scope, new studies have indicated that Adler’s theory may have relevance with other cultures. The first born son may have more positive life outcome expectations due to prevailing cultural sentiments, which includes decision making for the family (Galanti, 2003). Birth order status may also be affected by gender, for example, roles in the family may be correlated with birth order and with expectations of caregiving and/or decision making. For the purposes of this paper, we examined the influence of youth sex and birth order on drug use and education outcomes. We tested the Adlerian Individual Psychology theory to evaluate the importance of birth order and gender on education and whether or not youth had ever used cigarettes, alcohol, or marijuana with a sample of youths living in Santiago, Chile. Adlerian theory has not been widely applied to diverse populations, and none in South America, therefore this theoretical framework could illuminate how family characteristics impact culturally different populations.

Birth Order and Adlerian Theory

Alfred Adler “was the first to develop a comprehensive theory of personality, psychological disorders and psychotherapy, which represented an alternative to the views of Freud” (Adler, 1964, p. ix–x). One facet of his complex body of work involves the importance of birth order for youth outcomes. Adlerian Theory suggests that birth order and the number of siblings affect a child’s potential. Adler called upon the importance of understanding the “Family Constellation”:

“It is a common fallacy to imagine that children of the same family are formed in the same environment. Of course there is much which is the same for all in the same home, but the psychic situation of each child is individual and differs from that of others, because of the order of their succession” (Adler, 1964, p. 96).

Scholars have shown that both psychological and actual birth order impact individual outcomes. They note that “although researchers have examined the effects of birth order on intelligence, achievement, and personality, many of these studies have insuperable flaws, and the best work has produced weak or inconsistent results” (Freese & Powell, 1998, p. 57). Issues that arise include “methodological difficulties, the likelihood of very small effect sizes (if any), and the uncertain theoretical status of birth position” (Stagner, 1986, p. 377). Contrary to these findings, more recent work holds to the strength of birth order as an important factor associated with different outcomes, especially for first-born individuals. For example, Sulloway (1996) studied evidence that examined the question of why some individuals—for him revolutionary scientists—rebel and achieve remarkable breakthroughs in their fields (i.e., Darwin). In his book he developed a strong theoretical stance on how birth order influences children’s outcomes within families. Sulloway (1996) claims that birth order has been criticized unfairly due largely to methodological issues, His discussion takes into account family dynamics of age, gender, class, and wealth to support the conclusion that “siblings raised together are almost as different in their personalities as people from different families” (p. xiii). From this point of view, Sulloway goes on to develop a complex narrative that interweaves biological and social sciences to show how family and birth order impact children’s outcomes. However, other scholars have suggested that across many outcomes, variation between siblings may be greater than variation between families, suggesting that much territory remains to be explored to understand the complex family dynamics which do affect life outcomes for individuals (Conley, 2004). In addition, Freese, Powell, & Steelman (1999) argue that birth order effects that extend beyond personal attributes to social attitudes are minimal. Still they note that “although we find no evidence supporting Sulloway’s theoretical claims, our results cannot be taken as an indictment of evolutionary perspectives” (Freese, Powell, & Steelman (1999), p. 236).

This paper looks at the effects of actual birth order on several variables. We recognize that Adler suggested that psychological birth order is of vital importance to understanding a subject’s interpretation of their situation in an environment (such as the family) (Adler, 1937). Studies have pointed to the usefulness in understanding psychological birth order; for example, one project looked at 134 school aged children using the White-Campbell Psychological Birth Order Inventory instrument and found support that psychological birth order effects coping skills (Pilkington, White, & Matheny, 1997). The validity of the White-Campbell Psychological Birth Order Inventory Instrument to further observe that psychological birth order effects may trump actual birth order has also been noted (Stewart & Campbell, 1998). Other more recent studies have examined psychological birth order with college students looking at: family atmosphere and personality (Stewart, Stewart, & Campbell, 2001); lifestyle issues (Gfroerer, Gfroerer, Curlette, White, & Kern, 2003); and multidemensional perfectionism (Ashby, LoCicero, & Kenny, 2003). However, research has consistently shown that looking at actual birth order offers useful insights. In his review of birth order articles from 1960 to 1999, Eckstein (1998) reported statistically significant birth order studies (though not psychological birth-order studies) and offers some support for works looking at actual birth order. His review specifically notes that research has shown personality differences among subjects according to four major categories: oldest, middle, youngest, and single (p. 482). As Adler suggested, individuals in families experience difference environments within the same family and some of those differences can be attributed to birth-order (Sullivan & Schwebel, 1996). In a study looking at ninety-three never-married firstborn, middle-born, and last-born undergraduate students, Sullivan & Schwebel found consistency with Adler’s theory in individuals’ relationship-cognitions (1996, p. 60). Another study looked at 154 students at a large southern univeristy to asses actual birth order on internal and external attributions and found that attributions differed by birth order for positive attributions (Phillips & Phillips, 1998). One study examined 900 undergraduates who were asked to locate their birth order, the birth order of the parents and that of their best friend. This study provided evidence that showed individuals who shared the same birth order were more likely to be romantically involved or have close relationships with other similar birth order individuals (Hartshorne, Salem-Hartshorne, & Hartshorne, 2009).

The field remains contentious. Other researchers have critized birth order scholarship on predicting only positive outcomes such as success in careers, test scores, and income (Argys, Rees, Averrett, & Witoonchart, 2006). Researchers suggest that useful information about youth outcomes can also be understood by examining risky behavior for children, such as drug use and sexual activity. For instance, a recent study, examined how understanding birth order within family dynamics could impact young African American college students:

“Connecting a link between birth order and alcohol would constitute a “within family” measure study. The concept of “within family” concentrates on individual siblings and their sibling birth positions. Investigation factors such as an individual’s sibling position in relation to alcohol consumption may facilitate a better understanding of college drinking patterns and other high-risk behaviors” (Laird & Shelton, 2006, p. 19).

Thus, it is helpful to approach international settings using Adler’s theories in order to examine if there are effects that the children’s birth order roles have on both positive (educational outcomes) and negative (high-risk drug use patterns) life choices.

Adler’s work has rarely been applied to an international context, but recent work points to its persisting relevance. From a study that took data from the Department of Human Services from various years (2003–2007) of over 95,000 people from twelve Sub-Saharan Countries researchers developed a framework using fixed effect regressions per country for understanding how birth order affects first born educational outcomes while accounting for SES and gender Tenikue & Verheyden, 2010.

Understanding how birth order and gender function within the context of diverse populations, in this case an international context, can be an important and vital area for researchers to explore. First, these studies further explain and improve culturally competent approaches for mental health practitioners and others interested in evidence-based work. Secondly, such work can contribute to the overall theory and literature on birth order.

However, assessing the effects of birth order have had mixed success (Solloway, 1996). To further contribute to our understanding of birth order effects on youth behaviors, and building upon the work of prior researchers (Jordan, Whiteside, & Manaster, 1982), we tested whether three theoretical models of birth order differentially accounted for variation in academic standing and substance use among community-dwelling adolescents in Santiago, Chile. These models were first suggested by Jorden, Whiteside, and Manaster (1982) as a way to test for possible birth order effects. These authors note that models were taken from previous research and consist of three slightly different ways of measuring birth order. The first model is called “research expedient” and takes into account first child only, the middle child, and the youngest including children who are the second child of only two children (Falbo, 1977; 1981). The second model is called “Adler’s birth order positions” and looks again at ‘only child’, but adds new levels of first child, the second child, the middle of at least three children in a family, and the youngest child not including the second child of two children (Shulman & Mosak, 1977). Finally, we used Shulman and Mosak (1977) as cited in Jordan, et. al (1982) family size model that takes into account family size (small, medium, or large) and then looks again at the birth order within those levels of family size. For example, this model considers the only child of a small, medium, or large family; then the model continues with first born; second born, middle children, and youngest children each within a small, medium, and large family. We chose the dependent variables, youth substance use and educational outcomes for the following reasons: first, studies have shown that these variables have some correlation with birth order (Laird & Shelton, 2006); secondly, drug use has been seen as a rising issue for populations in Latin America, and one way to treat this problem is through examining educational outcomes.

In the present study we used these three definitions of birth order to account for differing opinions as to the efficacy of birth order studies. This work then can contribute to the birth order literature by testing models that take into account the expedient research, Adler’s birth order position, and family size definitions of birth order. To date, we are not aware of any studies that have tested more than one model of birth order simultaneously and that have examined Latin American populations for understanding how birth ordering and gender may be associated with youth educational outcomes and substance use and misuse.

Method

This study used cross-sectional data from the Santiago Longitudinal Study, a NIDA-funded study of adolescents and their families in Santiago Chile. Participants included 946 youth (mean age 14 years, 50% male) from municipalities of mid- to low- socioeconomic status. Participants were recruited from a sample of approximately 1,200 youth who several years earlier had participated in a study of iron and nutritional status at INTA (Lozoff, et al., 2003). In 2008–2010, youth completed assessments that consisted of a 2-hr interviewer-administered questionnaire with comprehensive questions on drug use, drug opportunities, and a range of individual, familial, and contextual variables. Youth and their parental caregiver (usually the mother) were brought to the interview site where the survey was administered by a licensed psychologist.

Measures

Dependent measurements

We used two latent factors as dependent variables. One is a latent factor representing substance use while the second is a latent factor measuring academic standing. The substance use latent factor is composed by three indicators of substance use – whether the respondent had ever used alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana. Each of these three indicators is a dummy-coded variable recording whether or not the adolescent has ever consumed alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana, respectively.

The academic standing latent factor is composed by four indicators about adolescents’ self report on their academic standing compared to their classmates. These four indicators correspond to four subjects; language arts, history, mathematics and science. These questions are from the Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) whereby for each of these subjects, adolescents were asked to indicate how they were doing in comparison to their peers. Response categories were as follows: “1=Failing”, “2=Below average”, “3=Average”, “4=Above average”.

Independent measurements

The main independent variable is birth order. As indicated earlier, in this study we tested theoretical models using three definitions of birth order: research expedient, Adler’s birth order position, and family size (Jordan, Whiteside, & Manaster, 1982).

According to the ‘Research Expedient’ operationalization of birth order, there are four categories: First born, only child, middle children and youngest including the 2nd of two. In our study we used first born as the reference category. Using “Adler’s birth order” definition, we operationalize birth order as having five categories: Only child, first born, second child, middle children at least of three and youngest excluding seconds. The reference category was first born. Finally, using a “Family size” definition, birth order is operationalized based on the combination of family size and birth order. Small families are defined as having only one or two children, middle families having three to four children and large families as having five or more children. Based on this categorization of family size there are twelve categories of birth order. However, because in our sample there were few cases in some of these categories we collapsed them into seven categories of birth order. These seven categories are: Only child, first of a small family, first of middle or large family, second of a small family, second of a medium or large family, third of a medium or large family and the youngest. The reference category is first of a small family.

The variables, age and socioeconomic status (SES), two continuous measures, were included as covariates. We used gender, based on youth self-report, as a grouping variable to test different estimations of the birth effect for males and females.

Analytic Methods

Using Multiple Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Covariates with categorical indicators and a threshold structure (Muthén & Muthén, 2009), we tested for gender differences in the effect of birth order on substance use -alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use-; and adolescent academic standing. The models -following standard practices of confirmatory analyses with covariates- were estimated in two steps: the measurement part of the model and the pathways. As for the measurement part, we confirmed the factor structure of both outcomes substance use and academic standing using confirmatory factor analyses. The measurement part also assumed presence of non-invariance in both factors structures, which was verified by the robust chi-square difference test with mean and variance adjusted test statistics as proposed by (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006).

The second part of the estimations tested for gender differences using multiple group estimations with covariates by gender. In this part, we tested three multi group models, one model for each of the three definitions of birth order (research expedient, Adler’s birth order, and Family size) to test for gender differences between the birth order categories. .In this part of the modeling the differential effects of birth order by gender were tested individually using one model per coefficient that was significant per type of birth order definition. Then, we combined all gender differences into one model and tested it against a model that assumes no gender differences. This step is critical to determine the existence of differential e effects by gender. Note that if a coefficient is significant in the model for males or females, it does not imply that the difference between the male coefficient and female coefficient is significant. The gender differences were tested against a model that assumes no gender differences. The test used for nested models was the robust chi-square difference test with mean and variance adjusted test statistics (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006).

Given that the factor indicators are categorical, the estimator used was WLSMV a weighted least square parameter estimate using a diagonal weight matrix with standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square test statistic that uses a full weight matrix, (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009). All models were estimated using MPLUS 5.21 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010).

Results

Tables 1a and 1b display the descriptive characteristics of the sample and variables. Most of the adolescents reported that they performed at an average or above average level regardless of their gender except in the case of mathematics where male adolescents reported standing above the average more than female adolescents. More than fifty percent of adolescent had not consumed alcohol, cigarette and more than eighty percent had not consumed marijuana.

Table 1.

| a Distribution of Substance Use Indicators and Academic Standing Indicators by Gender (481 Males and 465 Females) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male % |

Female % |

Male % |

Female % |

||

| Academic standing | Substance use | ||||

| English | Cigarettes | ||||

| Failing | 6 | 4 | Not consumed | 65 | 64 |

| Below average | 16 | 14 | Consumed | 35 | 36 |

| Average | 59 | 59 | Alcohol | ||

| Above average | 19 | 23 | Not consumed | 54 | 58 |

| History | Consumed | 46 | 42 | ||

| Failing | 4 | 3 | Marijuana* | ||

| Below average | 17 | 14 | Not consumed | 84 | 89 |

| Average | 55 | 60 | Consumed | 16 | 11 |

| Above average | 25 | 23 | |||

| Math* | |||||

| Failing | 10 | 9 | |||

| Below average | 18 | 24 | |||

| Average | 46 | 48 | |||

| Above average | 26 | 19 | |||

| Science | |||||

| Failing | 4 | 3 | |||

| Below average | 12 | 15 | |||

| Average | 58 | 59 | |||

| Above average | 26 | 23 | |||

| b Distribution of Birth Order and Mean and Standard Deviation for Age by Gender (481 Males and 465 Females) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male % |

Female % |

||||

| Birth order | |||||

| Research expedient | |||||

| Only | 7 | 10 | |||

| First | 30 | 28 | |||

| Middle | 28 | 26 | |||

| Youngest | 35 | 37 | |||

| Adler | |||||

| Only | 7 | 10 | |||

| First | 30 | 28 | |||

| Second | 34 | 33 | |||

| Middle | 11 | 9 | |||

| Youngest | 18 | 20 | |||

| Family size | |||||

| Only Child | 7 | 10 | |||

| First of small family | 20 | 17 | |||

| First of medium/large family | 11 | 11 | |||

| Second of small family | 17 | 16 | |||

| Second of medium/large family | 17 | 17 | |||

| Third order with at least one younger sibling | 11 | 9 | |||

| Youngest med family | 18 | 20 | |||

| Age | |||||

| Mean | 14.29 | 14.36 | |||

| Std. dev. | 1.43 | 1.41 | |||

gender differences p<0.05.

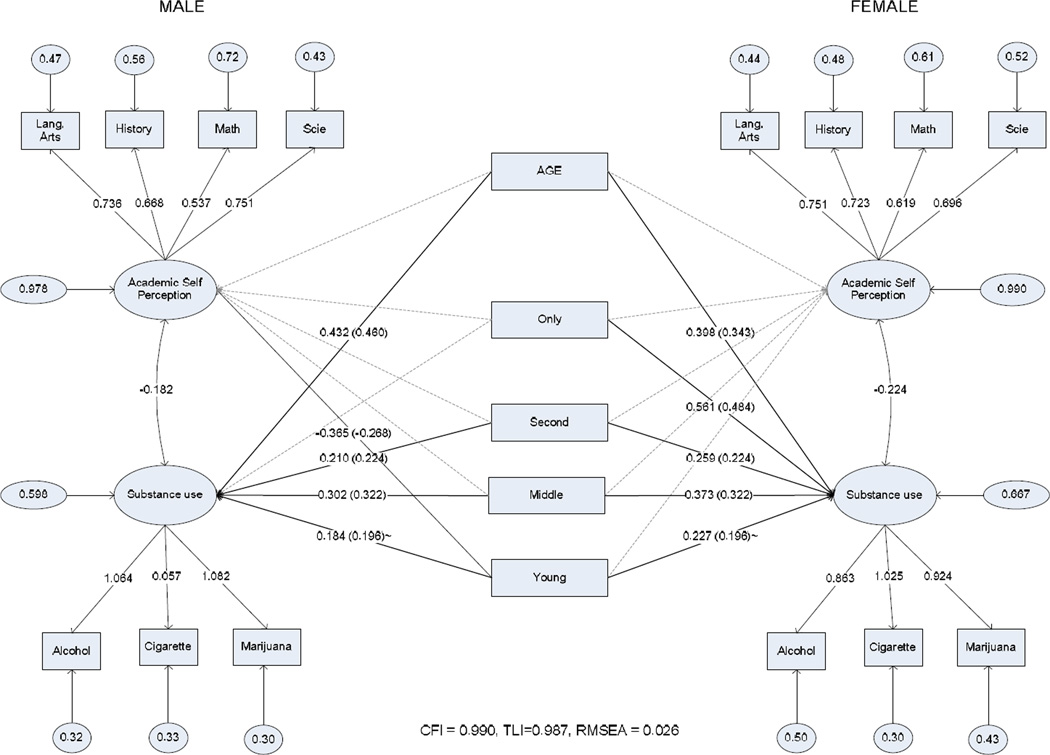

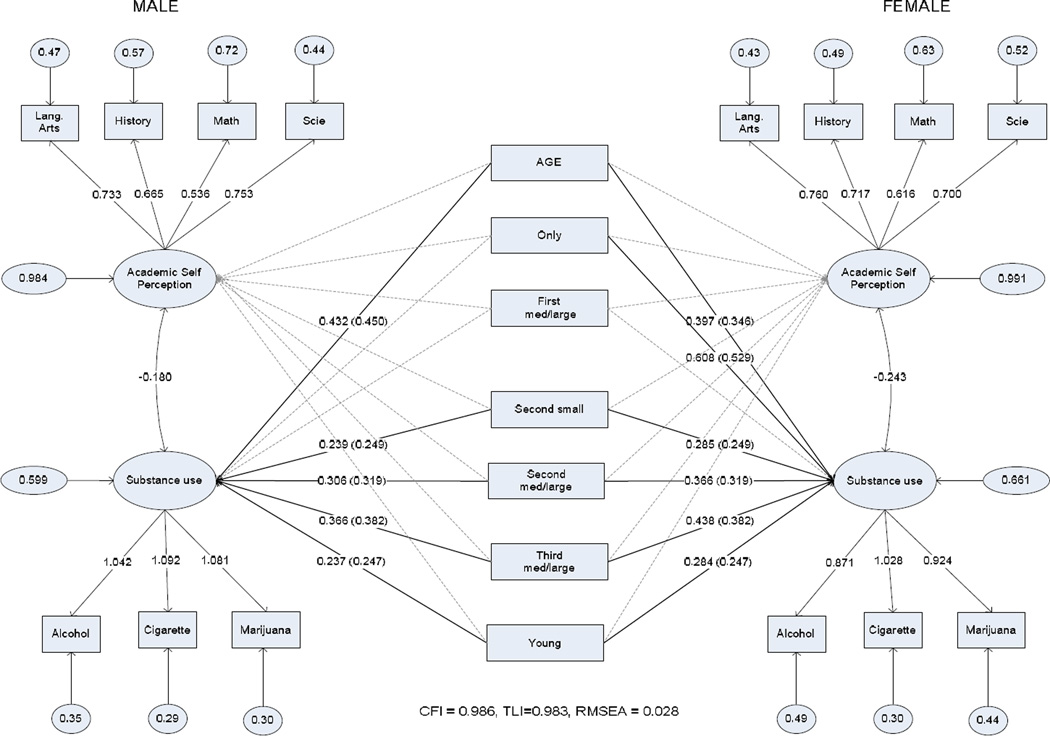

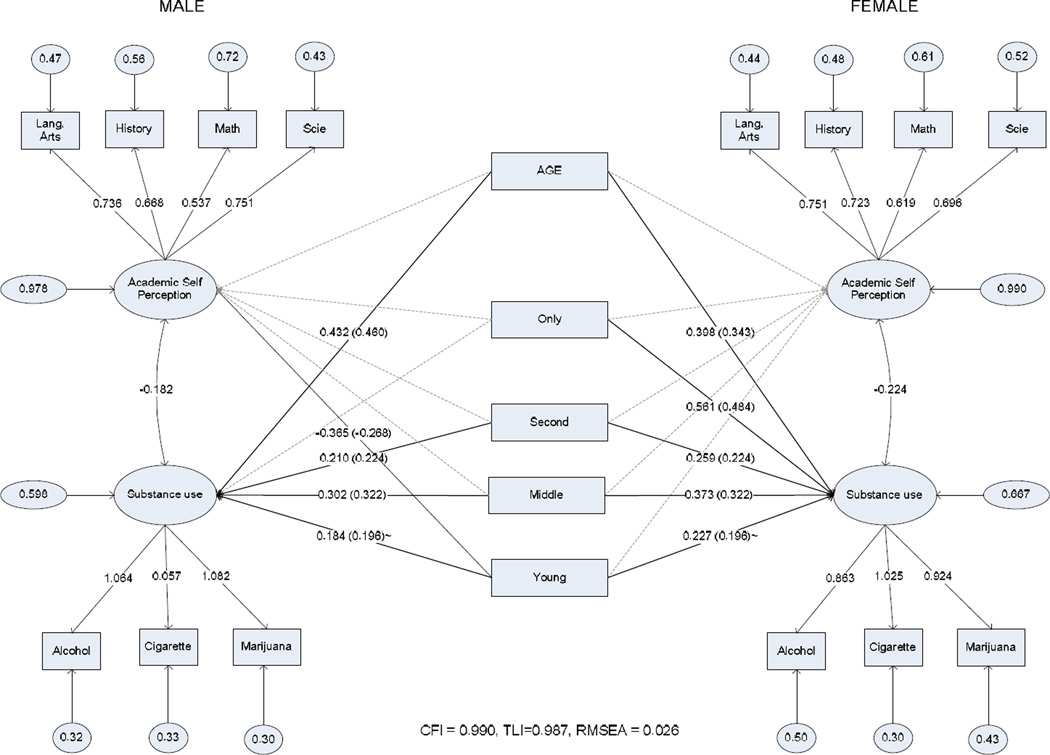

Table 2 shows the results of the gender comparison of the significant birth order coefficients for each one of the three birth order definitions. Figures 1 to 3 depict the results for each one of the three set of models estimated by gender. Each is described next.

Table 2.

Model Comparison Test Based on Constraining Birth Order Coefficients to be Equal Between Male and Females (481 Males and 465 Females)

| Coefficient tested | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Chi-Square Test for Difference Testing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | DF | ||||

| Research expedient | |||||

| Young on academic standing | 0.989 | 0.985 | 0.031 | 3.689 | 1 |

| Only on substance use | 0.986 | 0.981 | 0.034 | 9.755 * | 1 |

| Middle on substance use | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.027 | 1.126 | 1 |

| Young on substance use | 0.992 | 0.989 | 0.026 | 0.514 | 1 |

| Model with combined constraintsa | 0.989 | 0.986 | 0.029 | 5.935 | 3 |

| Full non invariant model | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.027 | ||

| Adler’s | |||||

| Second on academic standing | 0.988 | 0.984 | 0.030 | 3.104 | 1 |

| Young on academic standing | 0.987 | 0.982 | 0.032 | 4.722 * | 1 |

| Only on substance use | 0.987 | 0.982 | 0.031 | 4.993 * | 1 |

| Second on substance use | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 1 |

| Middle on substance use | 0.990 | 0.987 | 0.027 | 0.534 | 1 |

| Young on substance use | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.026 | 0.024 | 1 |

| Model with combined constraintsb | 0.990 | 0.987 | 0.026 | 3.233 | 4 |

| Full non invariant model | 0.990 | 0.986 | 0.028 | ||

| Family size | |||||

| Young on academic standing | 0.985 | 0.982 | 0.028 | 3.805 | 1 |

| Only on substance use | 0.986 | 0.983 | 0.028 | 3.902 * | 1 |

| Second small on substance use | 0.989 | 0.987 | 0.025 | 0.457 | 1 |

| Second/med/large on substance use | 0.988 | 0.986 | 0.025 | 1.060 | 1 |

| Third small/med/large on substance use | 0.989 | 0.986 | 0.025 | 0.778 | 1 |

| Young on substance use | 0.989 | 0.987 | 0.024 | 0.005 | 1 |

| Model with combined constraintsc | 0.986 | 0.983 | 0.028 | 6.990 | 5 |

| Full non invariant model | 0.988 | 0.986 | 0.025 | ||

p<0.05.

Constraining young on academic standing, middle, and young on substance use.

Constraining second on academic standing, second, middle and young on substance use.

Constraining all variables tested except only on substance use.

Notes. All models were nested in and compared to the full non-invariant model. All constraints in coefficients are set to be equal coefficient for male and female adolescents.

Figure 1. Research Expedient model: Birth order effect on substance use and academic standing. (481 males and 465 females).

Notes. Solid lines indicate significant path or correlations at p<0.05 otherwise indicated (p<0.01). Dotted lines indicate non significant paths. The coefficients for second, middle and young on substance use were constrained to be equal among male and female adolescents. All coefficients are standardized and numbers in parenthesis report non-standardized coefficients.

Figure 3. Family size model: Birth order effect on substance use and academic standing (481 males and 465 females).

Notes. Solid lines indicate significant path or correlations at p<0.05 otherwise indicated (p<0.01). Dotted lines indicate non significant paths. The coefficients for middle and young on substance use were constrained to be equal among male and female adolescents. All coefficients are standardized and numbers in parenthesis report non-standardized coefficients.

The results shown in Table 2 indicate that the effect of birth order varies by gender in two coefficients, according to the robust chi-square difference test with mean and variance adjusted test statistics (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006). These two coefficients are ‘only child’ on ‘substance use’ and ‘young’ on ‘academic achievement’. The effect of ‘only child’ on ‘substance use’ compared to ‘first child’ depends on gender across the three types of birth order definitions Research expedient (χ2 = 9.755, p < 0.05), Adler (χ2 = 4.993, p < 0.05) and Family size (χ2 = 3.902, p < 0.05). The effect of young on academic standing varies by gender only in the case of Adler’s definition of birth order. . Below we describe in detail each one of these three models.

Research expedient model

Figure 1 depicts the results for this model. The overall fit of the model was very good (CFI = 0. 986, TLI=0. 986 and RMSEA = 0.029). Compared to first born adolescents, adolescents who were the only child (β = 0.563, p < 0.05), or were born in between siblings (β = 0.322, p < 0.05), or were the youngest (β = 0.221, p < 0.05) were more likely to have ever consumed substances (alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana). From these three coefficients, only the coefficient for being the only child was different between males and females. A significant association was present only in the case of female adolescents while in the case of males there was no difference in the consumption of substances between being only child and being the first born.

Adler’s birth order position model

Figure 2 displays the results for this model. The overall fit of the model was very good (CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.987 and RMSEA = 0.026). Compared to adolescents who were born first, there were associations with substance use for the other four birth order possibilities, a finding similar to those of the Research Expedient described above. Essentially, when compared to adolescents who were born first, those who were an only child (β = 0.561, p < 0.05), second order (β = 0.259, p < 0.05), were born between siblings (β = 0.373, p < 0.05), or were the youngest (β = 0.227, p < 0.05) were more likely to have ever consumed substances. From these four associations, only those of being the only child varied by gender. Females who were only child were more likely to have ever consumed substances (alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana) while male adolescents born as only child did not differ on their consumption of substances compared to first born adolescents. In addition, we also found differential associations for the case of being the last child on academic standing. Specifically, only male adolescents who were the last born were less likely to express better academic standing than male adolescents who were born in first order (β = −0.365, p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Adler’s birth order position model: Birth order effect on substance use and academic standing (481 males and 465 females).

Notes. Solid lines indicate significant path or correlations at p<0.05 otherwise indicated (p<0.01). Dotted lines indicate non significant paths. The coefficients for second small, second med/large, third and young on substance use were constrained to be equal among male and female adolescents. All coefficients are standardized and numbers in parenthesis report non-standardized coefficients.

Family size model

Figure 3 presents the results for this model. The overall fit of the model is very good (CFI = 0.986, TLI = 0.983 and RMSEA = 0.028). As was the case with the Research Expedient and Adler’s models, there were only differential or moderated associations in the case of adolescents who were born as an only child compared to being the first child in a small family. Female adolescents were at greater risk of having ever consumed substances (β = 0.608, p < 0.05), while there was no association for male adolescents. In addition, this model shows detrimental effects for those adolescents who were born second in a small family (β = 0.285, p < 0.05), born second in a medium or large family (β = 0.366, p < 0.05), born in third order in a medium or large family (β = 0.438, p < 0.05), and being the youngest (β = 0.284, p < 0.05). All of these adolescents were more likely to have consumed substances than first born adolescents in small families.

Discussion

We found support for the Adlerian theory of individual psychology in the context of a large sample drawn from a non-U.S. population. This study adds some insights into how family dynamics within a Latin American population may contribute to youth educational and substance use outcomes. For all models tested (Research Expedient, Adler’s birth order, and Family Size), being the first born male was a protective factor against substance use. This was also true for first born females. For educational outcomes, birth order plays a different role. The research expedient model and the family size order showed no significance. However, under Adler’s birth order model being the first born does have an effect on better academic standing compared only to the youngest. In other words, being the youngest places the adolescent at risk of performing less well compared to older adolescents in their classrooms. One possible reason is that adolescents who are the youngest might be raised in more disadvantaged conditions than adolescents born first, especially in the case of poor families in Santiago, Chile. First born children may benefit not only from more parental attention, but also these children may receive more financial resources that can be allocated to their education. However, the results of our analyses controlling for SES and not controlling for SES were practically identical suggesting that SES may not serve to explain the findings. Furthermore, being a younger or youngest child may impact the amount of parental attention (in this case less), while also not receiving financial supports due to the possibility that low-income families may struggle with meeting the basic needs of a larger family.

We conclude that birth order may play some role with regard to substance use outcomes for youth in the Latin American country of Chile. Adler’s theory does indeed explain outcomes for a population of Santiago youths. Further studies taking into account family influences are recommended, especially in understanding the complexities of family relationships and motivations with regards to education and substance use. In addition, this information provides useful information for health care practitioners (psychologists, social workers, health care providers, and others) who work with Hispanic/ Latino populations in the United States and for those working with populations in South America. Understanding the importance of birth order and the strains and privileges of individual children within their birth order may help guide proper treatment and services. Finally, the contribution of looking at three different models of testing birth order (Research Expedient, Adler’s birth order, and Family Size), offered some useful insights for future researchers. We conclude that more attention should be given to the research design and methods used to address birth order effects. Also, such studies would benefit from addressing psychological birth order effects rather than only actual birth order effects; the inability of our dataset to address psychological birth order effects (which is at the heart of Adler’s theory) is indeed a limitation of our work. Other limitations impact our dependent variables. We used two latent factors as dependent variables. One is a latent factor representing substance use while the second is a latent factor measuring academic standing. We note that results considering birth order profile out whether the subject uses substances habitually or if this were only a one time use, and this might obscure the outcomes. We call for future work to include more refined measurements in the survey instruments to account for these differences. Also, the education variable is self-reported and is difficult to interpret. We would have preferred to have used standardized test scores results or some other objective measure, but we were unable to attain those data. Regardless, the results from this study do indicate that Adler’s framework can be an important doorway into studying international populations.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: ASEBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. Position in family constellation influences lifestyle. International Journal of Individual Differences. 1937;3:211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. In: Problems of Neurosis: A Book of Case Histories. Mairet P, editor. New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Allison K. Academic stream and tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among Ontario high school students. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27:561–570. doi: 10.3109/10826089209063468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argys LM, Rees DI, Averrett SL, Witoonchart B. Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior. Economic Inquiry. 2006;44(2):215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby JS, LoCicero KA, Kenny MC. The Relationship of Multidimensional Perfectionism to Psychological Birth Order. Journal of Individual Psychology. 2003;59(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Robust Chi-Square Difference Testing with Mean and Variance Adjusted Test Statistics. 2006 Retrieved 2010 йил 25-August from Mplus Web Notes: No. 10: http://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/webnote10.pdf.

- Bachman J, O’Malley P, Schulenberg J, Johnston L, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith E. The education-drug use connection: How sucesses and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. New York: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen H, Martin G, Roeger L, Allison S. Perceived academic performance and alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use: Longitudinal relationships in young community adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendy JA, Maldonado R. Genetic analysis of drug addiction: the role of cAMP response element binding protein. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 1998;76(2):1432–1440. doi: 10.1007/s001090050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Hechathorn DA. AIDS Prevention Outreach among Injection Drug Users: Agency Problems and New Approaches. Society for the Study of Social Problems. 1994;41(3):473–495. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat H, Dishion T, Anthony J. Parent monitoring and the incidence of drug sampling in urban elementary school children. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;141:25–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley D. The Pecking Order: A Bold New Look at How Family and Society Determine Who We Become. New York, New York: Vintage Books: A Division of Random House, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein D. Empirical Studies Indicating Significant Birth-Order-Related Personality Differences. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1998;56(4):481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Falbo T. Relationships between birth category, achievement and interpersonal oreintation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;41:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Falbo T. The only child: a review. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1977;33:47–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese J, Powell B. Review of Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives by Frank J. Sulloway. Contemporary Sociology. 1998;27(1):57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Freese J, Powell B, Steelman LC. Rebel Without A Cause or Effect: Birth Order and Social Attitudes. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(2):207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Galanti G-A. The Hispanic Family and Male-Female Relationships: An Overview. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14(3):180–185. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Vlahov D, Coffine PO, Fuller C, Leon AC, et al. Income distribution and risk of fatal drug overdose in New York City neighborhoods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;70(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer KP, Gfroerer CA, Curlette WL, White J, Kern RM. Psychological Birth Order and the BASIS-A Inventory. Journal of Individual Psychology. 2003;59(1):30. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne JK, Salem-Hartshorne N, Hartshorne TS. Birth order effects in the formation of long-term relationships. Journal of Individual Psychology. 2009;65(2) [Google Scholar]

- Hays S. Structure and Agency and the Sticky Problem of Culture. Sociological Theory. 1994;12(1):57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Hawkins J, Catalano R, Abbott R, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan E, Whiteside M, Manaster G. A practical and effective research measure of birth order. Individual Psychology, Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;38:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kozel NJ, Adams EH. Epidemiology of Drug Abust: An Overview. Science. 1986;234:970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.3490691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer K, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural Sensitivity and Adaptation in Family-Based Prevention Interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3(3):241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird TG, Shelton AJ. From an Adlerian Perspective: Birth Order, Dependency, and Bing Drinking on a Historically Black University Campus. The Journal of Individual Psychology. 2006;62(1):18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino Health in the United States: A Review of the Literature and its Sociopolitical Context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leman K. The New Birth Order Book: Why you are the way you are. Revell; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User's Guide, Sixth Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User's Guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AS, Phillips CR. Birth-Order Differences in Self-Attributions for Achievement. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1998;56(4):474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington LR, White J, Matheny KB. Perceived Coping Resources and Psychological Birth Order in School-Aged Children. Individual Psychology. 1997;53(1):42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman B, Mosak H. Birth order and ordinal position: Two Adlerian views. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1977;33:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solloway FJ. Born to Revel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives. New York: Pantheon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stagner BH. The Viability of Birth Order Studies in Substance Abuse Research. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21(3):377–384. doi: 10.3109/10826088609074841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AE, Campbell LF. Validity and Reliability of the White-Campbell Psychological Birth Order Inventory. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1998;54(1):41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AE, Stewart EA, Campbell LF. The Relationship of Psychological Birth Order to the Family Atmosphere and to Personality. Journal of Individual Psychology. 2001;57(4):363–387. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan BF, Schwebel AI. Birth-Order Position, Gender, and Irrational Relationship Beliefs. Journal of Individual Psychology. 1996;52(1):54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Table 1a. Projected Population of the United States, by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2000 to 2050. U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. Jan, йил, From. [Google Scholar]

- Tenikue M, Verheyden B. Birth Order and Schooling: Theory and Evidence from Twelve Sub-Saharan Countries. Journal of African Economies. 2010;00(00):1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Williams GH. The determinants of health: structure, context, and agency. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2003;25:131–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. association between parental alcohol-related behaviors and children's drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]