Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate college freshmen’s views towards potential social networking site (SNS) screening or intervention efforts regarding alcohol.

Participants

Freshmen college students between February 2010 and May 2011.

Methods

Participants were interviewed, all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Qualitative analysis was conducted using an iterative approach.

Results

A total of 132 participants completed the interview (70% response rate), the average age was 18.4 years (SD 0.49) and 64 were males (48.5%). Three themes emerged from our data. First, most participants stated they viewed displayed alcohol content as indicative of alcohol use. Second, they explained they would prefer to be approached in a direct manner by someone they knew. Third, the style of approach was considered critical.

Conclusions

When approaching college students regarding alcohol messages on SNSs, both the relationship and the approach are key factors.

Keywords: Alcohol, Counseling, Health Education

Alcohol use is a major cause of both morbidity and mortality among college students.1 Almost half (44%) of college students report binge drinking, and almost one fifth of students report frequent binge drinking. Frequent binge drinkers are more likely to experience serious health and other consequences of their drinking behavior compared to other students. As many as 1700 college student deaths each year are alcohol-related and approximately half of students who use alcohol report direct alcohol-related harms.2-6 Among undergraduates, college freshmen are at highest risk for alcohol problems, likely related to their newfound independence and decreased experience with alcohol compared to upperclassmen.7 Preventing the negative consequences associated with alcohol use requires both screening to identify those at risk and intervention directed towards those who suspected of being at risk. Screening tools are available to identify college students at risk for problem drinking.8-10 However, a large scale approach to screening among college students remains challenging as many students do not seek routine or preventive health care at student health centers.11, 12

The social networking site (SNS) Facebook may provide an innovative approach towards the initial identification of college students at risk for problem alcohol use. SNSs such as Facebook are popular among and consistently used by college students; current data suggests between 94 and 98% of students maintain a Facebook profile and most report daily use.13-15 Facebook allows students to create a personal web profile, communicate with friends and build an online social network.16, 17 Increasingly, SNSs are being used for research to investigate adolescent and young adult attitudes and characteristics.18 The nature of SNSs allow large amounts of identifiable information to be revealed and disseminated and thus collected as data.19 References to alcohol use are common on SNSs; up to 83% of college students’ Facebook profiles reference alcohol.20, 21 These references may be displayed on status updates, which are personally written text displayed on a public “wall” on the profile. One example may be, “Tom got really drunk last weekend!” References may also be displayed in personal pictures, such as a photograph of the profile owner holding a bottle of beer. References may also be displayed through downloaded icons, often called “bumper stickers” which show humorous quotes or images. One example is, “Let’s get embarrassingly drunk and end the evening with a variety of bad choices.” Previous work has illustrated that display of references to intoxication or problem drinking on Facebook are associated with being identified as at increased risk for problem drinking using a validated clinical screening tool.22 Thus, displayed references to problem drinking on Facebook profiles may be a means of early identification of students who are at risk for negative health consequences associated with alcohol use.

If references to problem drinking on Facebook profiles can provide an accurate means of identifying those within a population who are at risk, there are several ways in which universities could incorporate Facebook into screening efforts. A first option is to systematically assess displayed information on publicly available Facebook profiles in order to identify students at risk, then approach these students and recommend that they undergo further screening or counseling. This Facebook assessment could be undertaken by a campus health care provider such as a counselor or nurse. A second option is to provide training to peer leaders on campus, such as dormitory resident advisors. These peer leaders would then be able to recognize displayed references to problem alcohol use on Facebook, approach the student regarding this concern, and recommend clinical screening.

Among potential barriers towards these screening approaches, one is how students would perceive being approached regarding displayed Facebook content. It is possible that they may perceive being screened for health behaviors via Facebook as an invasion of privacy. A previous study evaluated college students’ views regarding privacy and information sharing and found that students perceived they disclosed more information about themselves on Facebook than in general, but that information control and privacy were important to them.23 Another study evaluated college students’ reactions to updated security settings on Facebook and found that the majority of respondents were upset over privacy policy changes because of a perceived loss of privacy control, even though there was no increase in the amount of information that was exposed.19 Thus, many SNS users state that privacy issues regarding displayed profile content are important to them, yet many users still choose to display large amounts of personal information online.23

In order to determine if Facebook has a place as an innovative complement to current screening approaches, several gaps in our understanding must be addressed. It remains unclear whether older adolescents believe there is an association between displayed Facebook references to alcohol and offline alcohol use. If college students perceive displayed alcohol references as indicative of alcohol use, they may better understand potential benefits of addressing alcohol references displayed on Facebook. It is possible that students and peer leaders could be future partners in screening and intervention efforts. It is also unclear if students have communication preferences for potential screening or intervention efforts using Facebook, and in what ways they are willing to communicate regarding their Facebook displays of alcohol use. Before next steps towards screening or intervention based on SNS content can take place, views of this population must be understood.

The purpose of this study was to explore freshmen college students’ perceptions of displayed references to Facebook alcohol use and their communication preferences if they were to be contacted regarding their displays of Facebook alcohol use.

METHODS

This study was conducted between November 1, 2009 and June 1, 2011 and received IRB approval from the University of Wisconsin.

Setting and subjects

Participants for this study were identified using Facebook (www.Facebook.com), the most popular SNS among our target population of college students.24, 25 As part of a larger ongoing study investigating college health behaviors and Facebook, we investigated publicly available Facebook profiles of freshmen undergraduate students within one large state university Facebook network. This university included approximately 5000 freshmen of whom approximately half are female and approximately 20% are of minority ethnic background. Because this study focused on evaluating alcohol screening approaches that could be applied to publicly available profiles, profile owners with private security settings were excluded. To be included in the study, profile owners were required to self-report their age as 18 to 19 years old and provide evidence of profile activity in the last 30 days. We only included profiles for which we could contact the profile owner to invite them to the interview by calling a phone number listed on either the university directory or Facebook profile.

Data Collection and Recruitment

We used the Facebook search engine to search for profiles within our selected university’s network among the freshmen undergraduate class. This search yielded 416 profiles, all of which were assessed for eligibility. The majority of profiles were ineligible because their profile owners were incorrectly included in the search results, including profiles in which the age was not 18 or 19 years old (N=36). Other profiles were excluded because no contact information (phone number or email) was listed within their Facebook profile or the university directory (N=83), or due to privacy settings (N=102). Of privacy exclusions, 87 profiles were fully private and 15 profiles had set the wall section to private. A total of 188 profiles were eligible for evaluation.

For profiles that met inclusion criteria, owners were called on their cell phone. After verifying identity, the study was explained and profile owners were invited to participate in an interview about college student health. Respondents who completed the interview were provided a $50 incentive.

Interviews

Interviews were one-on-one with a trained female interviewer. After explaining the study and obtaining consent, participants completed several health measures for the ongoing study. Participants were then told: “In some of our research studies we have found that many college students display references to alcohol on their Facebook profiles such as bumper stickers, pictures and status updates. What do you think those alcohol references mean when they are on bumper stickers?” After the participant answered, the interviewer then asked: “What do you think those alcohol references mean when they are in displayed personal photographs?” The interview then asked: “What do you think those alcohol references mean when they are on status updates?”

After completing these questions, participants were asked the following series of questions: “If one of your friends saw something on your profile that made them worried about you regarding alcohol, how would you want them to communicate with you about that?” The interviewer then asked: “If somebody who didn’t know you as well, like a resident advisor or professor saw something on your profile that made them worried about you regarding alcohol, how would you want the individual to communicate with you about that?” Finally, the interviewer asked: “If somebody who had never met you in person saw something on your profile that made them worried about you regarding alcohol, how you would want that individual to communicate with you?” Interviews were audio recorded.

Analysis

All interviews were fully transcribed by three trained research assistants; one investigator reviewed 25% of transcriptions to ensure accuracy. Two investigators (KE, MM) then conducted analyses using an iterative process in which transcripts were reviewed to characterize the interview responses, and then discussed to reach consensus on themes. These themes were then reviewed with 2 other investigators (AG, LK) who participated in data collection to ensure consensus on the thematic representations of the data amongst all analysis participants.

RESULTS

A total of 132 participants completed the interview (70% response rate), the average age was 18.4 years (SD 0.49) and included 64 males (48.5%). (Table 1) Three themes emerged from our data. First, the vast majority of participants stated that they viewed displayed Facebook alcohol content as indicative of alcohol use. Second, participants explained that they would prefer to be approached by someone they knew regarding content of their profile, and approached in a direct face-to-face manner. Most participants did not want to be approached by a stranger, but those who did preferred an indirect manner such as using Facebook or email. Finally, the style of approach was considered critical; participants wanted the approach to include asking questions about profile content rather than implying judgment without discussion.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information (N=132)

| Gender | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 64 (48.5%) |

| Female | 68 (51.2%) |

| Age | |

| 18 | 75 (56.8%) |

| 19 | 57 (43.2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 120 (91.6%) |

| Asian American | 5 (2.8%) |

| African American | 1 (0.8%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (0.8%) |

| Mixed/Other | 4 (3.2%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8%) |

Theme 1: Displayed alcohol use is indicative of offline alcohol use

Our first theme was that displayed alcohol content on Facebook was an accurate portrayal of alcohol use. Representative quotes included:

“That person drinks, like it’s almost a definite.”

“If I saw it on someone’s profile I’d just assume that they drink.”

“They want you to know that that’s how they spend their time. Maybe to try to make other people want to be friends with them.”

“That they drink, how much they drink, and to show that they do that kind of stuff.”

Other participants elaborated on these views, stating that references were believable at face value if they were in pictures or status updates, one participant stated “if they had a [status update] alcohol reference, I’d say alcohol is a bigger part of their life than if they had a picture or a bumper sticker.” Reasons that motivate college students to display alcohol use included wanting to identify oneself as a drinker. One explained “they want to be seen as a guy that drinks.” Another commonly suggested reason was to display that one is living the “typical” college student life of drinking and partying. One participant explained: “that’s just part of the culture. You know, Friday and Saturday night, unless it’s midterms or exam week, people usually go out and drink. So, it’s like social, I don’t know, it happens. To put it on your profile is like the social norm. To show that you participated in what everyone was doing last night.”

Theme 2: Communication preferences

When considering the approach someone may take to address worrisome alcohol references, participants uniformly expressed a preference to be approached by someone they knew. Commonly expressed was the view that students would be most receptive to being approached by a friend in person. Representative quotations include:

“I would just want them to tell me because then I could deal with it as soon as possible. I might not interpret something as being wrong, but they might know me better or realize something is wrong and I’d be able to solve the problem as soon as possible.”

“Just talk to me, I’m pretty straightforward about that sort of thing. I prefer direct confrontation, which I’ve done with other friends and I’d want them to do the same with me.”

“I would prefer them to say something in person to me.”

Most profile owners were also open to communication about profile content with people not as well know to them, such as a resident advisor or professor. Suggestions included more variety in how this communication could take place compared to communication preferences that applied to peers. Resident advisors were commonly viewed similarly to peers, while professors were often grouped similar to the ‘people not known to you’ category. There appeared to be more concern about privacy in these approaches. Representative quotations explaining their preferred communication venues with people who are somewhat known to them, such as resident advisors or professors, include:

“Probably still talk to me directly, but in private, not like in a front of a big crowd of people.”

“Probably email me to set up a time to talk.”

“Communicate directly, but not near other people.”

“Well, for [resident advisor], I’d say that doesn’t really apply to me, because mine lives right across the hall and we’re like really good, close and things like that. I wouldn’t mind him just coming right up to me. But professors and things like that…I don’t know, I’d think maybe an email or something mentioning that they’d like to talk about it and then like a face-to-face meet up or something.”

Participants were generally negative towards being approached by someone not known to them. Representative quotations include:

“I would prefer that they never communicate it to me at all. If they’ve never met me, that would make me feel a little creeped out. It depends on who they are I guess, if they’re like ‘I’m from the department of whatever and I see you have whatever on your Facebook and there might be some issues’, then I guess maybe send me an email? But if it’s a stranger, I don’t understand why they would communicate that to me.”

“If someone approached you like that I think my immediate response would be like, wow, Facebook stalker.”

“I think I would reevaluate some of the things I do, but I would take it less seriously. Like it would matter, but I’d be a little offended.”

A few participants explained that if someone not known to them was to contact them, they would prefer a more indirect approach such as by email. One explained,: “It would be weirder if they did it face to face. If they did it electronically somehow it would be less weird, I’m not sure how they would do that, but if they did it that way it would be less of a weird level. Facebook is there to communicate with people.”

Alternatively, a few expressed that they would prefer that the stranger talk to one of their own friends and ask that person to communicate the concern.

“That’s kind of odd, because I almost feel like they wouldn’t know me well enough. Because you can misconstrue things. I’d say, like maybe they could ask someone who knows me, like a close friend of mine about it and then if they were still concerned that I should be talked to about the problem, then talk to me.”

One participant described an event in which concerns were relayed through a friend of the friend. This person explained a recent scenario in which Facebook was used as a communication venue between two people who were worried about a mutual friend. “He told me he was a little bit worried about my roommate because he, he drinks. He doesn’t drink that much but he’s starting to a little bit more, [my roommate’s friend] was actually talking to me on Facebook about how he was getting a little worried and he was like, ‘keep an eye on him, watch him.’ It’s hard to come straight out and tell someone. I think there is a line that once they cross it you have to come out and say something ‘cause they are endangering themselves. You should say something like: ‘I think you’re drinking too much, I think you should slow down.”

Theme 3: Communication style

A common theme across all potential communication partners was the preferred style of communication. Participants uniformly agree that an open but direct style of communication was preferable. One participant described, “I’d rather have people just come up to me. I don’t like when they beat around the bush about things. Just say: ‘Hey, I saw this on Facebook and I’m a little worried.”

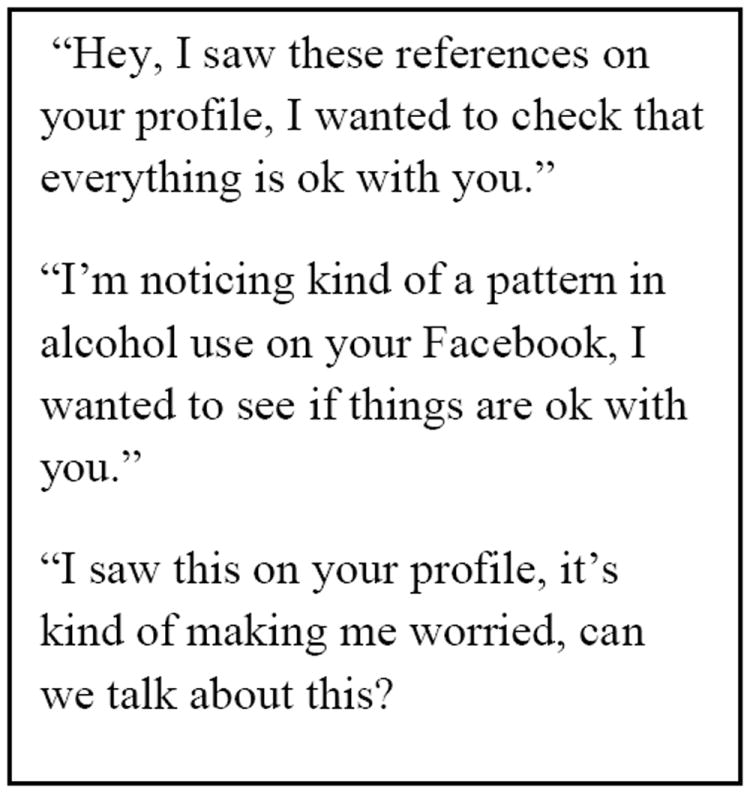

Participants described wanting the communication to begin with a statement of what was noticed on the profile, and questions about what it may mean. This is in contrast to noticing something on Facebook and providing a direct comment or interpretation of the reference. One participant describing the approach as, “Probably just be straight up about it, not writing a comment like “you’re drinking a lot,” but asking me “why are you drinking a lot.” Participants commonly voiced they wanted the discussion to be without judgment or quick advice. One participant explained his preferred approach was: “Probably like respectfully, not like blaming me.” Figure 1 illustrates several suggested examples from study data describing how to approach a peer if one was worried about their drinking based on Facebook displays.

Figure 1.

Examples of potential statements to use if approaching a college student regarding displayed alcohol references on their Facebook profile

Another common concern was that the intention of the person’s approach was critical to the acceptance or rejection of the intervention approach and message. If a student perceived that the intentions were to help, or that the person who initiated the conversation cared, this was perceived more positively. One participant was asked how this communication could take place and replied, “In any way, calling, texting Facebook message. I like that, people care about you, so any way is fine.”

Participants also brought up that using Facebook as a medium for discussion, rather than a focus on real offline events, could make a difficult discussion easier. A few participants explained that discussing Facebook events may allow for a feeling that the situation is removed and the discussion is about Facebook displays rather than behavior. Thus the discussion could be framed around what the person chose to display, rather than a judgment of who they were. One participant commented, “I’d just want her to tell me, like “look, this [reference on Facebook] could be perceived in this manner and in case you’re not aware of that, I’m just telling you.”

COMMENT

The main findings from this study include that alcohol references on Facebook are taken at face value by peers and that when approaching college students regarding alcohol messages on SNSs both the relationship and the approach are key factors in whether the message is heard.

First, our findings regarding displayed alcohol content interpreted at face value by peers share similarities with our previous work with younger adolescents.26 Participants generally believed that displayed alcohol references on Facebook could most often be taken at face value. Thus, peers may be viable partners for screening efforts as they already view displayed alcohol references as salient and believable. Further, our data suggest that approximately half of profiles were excluded due to privacy settings. Since the time of our data collection, Facebook profile security settings have again changed and more options exist to set sections of the profile to private while leaving the profile itself publicly available. It is possible that more profiles may now be publicly available. As Facebook security is ever-changing, it is likely that an ideal target to undertake initial screening is someone known to the college student who would have full access to their profiles’ content. This approach may also lead to better acceptance by the profile owner if he or she is approached with concerns and a recommendation to undergo further clinical screening.

Second, our findings regarding communication preferences suggest that mass screening efforts centered in college health settings are likely to be met with resistance if the screener is not known by the student. However, it is possible that peer leaders such as dormitory resident advisors may be key partners in future SNS screening and intervention efforts. These peer leaders could be trained to recognize displayed alcohol references that are consistent with intoxication or problem drinking and provided counseling skills to encourage students to seek further screening at a student health center. Previous work with peer interventions has shown successes in areas such as improved sex education and reduced drug and alcohol –related harm. 27-29 It is also possible that universities could incorporate consideration of Facebook alcohol displays and ways to discuss potential concerns with peers as part of their freshmen college orientation messages about alcohol.

Third, our findings suggest that focusing on communication style would be critical to any successful screening and intervention program. The features discussed by participants as desirable in a communication intervention included being direct and respectful, showing empathy, and asking questions with a nonjudgmental approach. These desirable communication characteristics share many features with currently recommended provider-patient communication approaches in alcohol clinical care settings, such as motivational interviewing.30-32 Motivational interviewing (MI) includes responding to interactions with patients with a person-oriented empathetic style. MI is often described as having two components, a relational component focused on empathy and a technical component focused on word choice.33 These two components mirror the two themes found in our data: the importance of the existing relationship based on empathy and trust, and the technical aspect of word choice when approaching the conversation. Thus, it is possible that extending motivational interviewing techniques to peer leaders may facilitate new directions in alcohol screening and interventions. Providing peer leaders with these concrete skills may empower them to feel confident in starting these difficult conversations when concerning alcohol references are noted on Facebook

Limitations

Our findings are limited in that we recruited participants from publicly available profiles on one SNS in one university. Since our study was intended to identify a sample of college freshmen with public Facebook profiles, this approach was purposeful. However, we cannot extrapolate our results to upperclassmen or other universities. Our findings are also limited in that they include a limited amount of minority students, which is consistent with the demographics of our university. Finally, our study was focused on the use of Facebook as a potential intervention tool, future study including other forms of social media such as Twitter or texting should be considered.

Conclusion

Study findings support that alcohol references on Facebook are taken at face value by peers. When approaching college students regarding concerning alcohol messages on SNSs, both the relationship with that student and the type of approach are critical factors in whether the message is heard. In considering future directions for SNS interventions regarding college student alcohol use, messages sent by known or trusted individuals are likely to be better received since peers accept alcohol displays at face value, peer leaders may be possible intervention partners. In designing future programs, motivational interviewing approaches could be considered as essential elements of training. Several potential intervention approaches are suggested by these findings. Colleges may choose to include Facebook evaluation in their training of resident advisors, as these peer leaders may be well positioned to identify problematic alcohol use on the Facebook profiles of their dorm residents and could suggest further clinical screening. It is possible that colleges may even consider more generalized Facebook evaluation training at their freshmen orientation so that peers can identify friends who may be struggling with problematic alcohol use and help facilitate further evaluation. All of these approaches require attention to privacy and student willingness to participate, thus, our data present a starting place for future intervention development.

Acknowledgments

The work described was supported by award K12HD055894 from NICHD and by award R03 AA019572 from NIAAA.

Contributor Information

Megan A. Moreno, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin

Allison Grant, Department of Education, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Lauren Kacvinsky, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Katie G. Egan, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin

Michael F. Fleming, Department of Family Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois

References

- 1.Association ACH. American College Health Association: National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Data Report Fall 2008. Baltimore: American College Health Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: a common problem among college students. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002 Mar;(14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009 Jul;(16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002 Mar;(14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giancola PR. Alcohol-related aggression during the college years: theories, risk factors and policy implications. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002 Mar;(14):129–139. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin KW Association AP. Handbook of Drug Use Etiology: Theory, Methods and Findings. Washington, DC: APA; 2009. The epidemiology of substance use among adolescent and young adults: A developmental perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokotailo PK, Egan J, Gangnon R, Brown D, Mundt M, Fleming M. Validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test in college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004 Jun;28(6):914–920. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128239.87611.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict. 1991 Nov;26(11):1173–1185. doi: 10.3109/10826089109062153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt A, Barry KL, Fleming MF. Detection of problem drinkers: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) South Med J. 1995 Jan;88(1):52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsac B. Blog, Twitter or Facebook for health. SportEX Health (14718154) 2008;(18):14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foote J, Wilkens C, Vavagiakis P. A national survey of alcohol screening and referral in college health centers. J Am Coll Health. 2004 Jan-Feb;52(4):149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The Taste for Privacy: An Analysis of College Student Privacy Settings in an Online Social Network. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008;14(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buffardi LE, Campbell WK. Narcissism and social networking Web sites. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008 Oct;34(10):1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009 Mar;25(2):578–586. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capitol and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12 [Google Scholar]

- 17.boyd d. Why Youth (Heart) Social Networking Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. In: Buckingham D, editor. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning: Youth, Identity and Media Volume. Cambridge, MA: MIT press; 2007. pp. 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackland R. Social Network Services as Data Sources and Platforms for e-Researching Social Networks. Social Science Computer Review. 2009 Nov;27(4):481–492. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoadley CM, Xu H, Lee JJ, Rosson MB. Privacy as information access and illusory control: The case of the Facebook News Feed privacy outcry. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. Jan-Feb;9(1):50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and Associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen C, Hsiao R, Ko C, et al. The relationships between body mass index and television viewing, internet use and cellular phone use: the moderating effects of socio-demographic characteristics and exercise. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43(6):565–571. doi: 10.1002/eat.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, Brockman LB, Becker T. Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christofides E, Muise A, Desmarais S. Information Disclosure and Control on Facebook: Are They Two Sides of the Same Coin or Two Different Processes? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009 Mar 1; doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Google. Google Ad Planner. [April 16, 2010];2010 https://www.google.com/adplanner/planning/site_details#siteDetails?identifier=facebook.com&geo=US&trait_type=1&lp=false.

- 25.Pempek TA, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;20(3):227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, Walker L, Christakis DA. Real use or “real cool”: adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on social networking websites. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Oct;45(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luchters S, Chersich MF, Rinyiru A, et al. Impact of five years of peer-mediated interventions on sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weeks MR, Convey M, Dickson-Gomez J, et al. Changing drug users’ risk environments: peer health advocates as multi-level community change agents. Am J Community Psychol. 2009 Jun;43(3-4):330–344. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spicer RS, Miller TR. Impact of a workplace peer-focused substance abuse prevention and early intervention program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005 Apr;29(4):609–611. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158831.43241.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York: Guilford Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tollison SJ, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Neil TA, Olson ND, Larimer ME. Questions and reflections: the use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behav Ther. 2008 Jun;39(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller WR, Rose GL. Toward a Theory of Motivational Interviewing. American Psychological Journal. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]