Abstract

Clinical trials and correlative laboratory research are increasingly reliant upon archived paraffin-embedded samples. Therefore, the proper processing of biological samples is an important step to sample preservation and for downstream analyses like the detection of a wide variety of targets including micro RNA, DNA and proteins. This paper analyzed the question whether routine fixation of cells and tissues in 10% buffered formalin is optimal for in situ and solution phase analyses by comparing this fixative to a variety of cross linking and alcohol (denaturing) fixatives. We examined the ability of nine commonly used fixative regimens to preserve cell morphology and DNA/RNA/protein quality for these applications. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Bovine Papillomavirus (BPV)-infected tissues and cells were used as our model systems. Our evaluation showed that the optimal fixative in cell preparations for molecular hybridization techniques was “gentle” fixative with a cross-linker such as paraformaldehyde or a short incubation in 10% buffered formalin. The optimal fixatives for tissue were either paraformaldehyde or low concentration of formalin (5% of formalin). Methanol was the best of the non cross-linking fixatives for in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. For PCR-based detection of DNA or RNA, some denaturing fixatives like acetone and methanol as well as “gentle” cross-linking fixatives like paraformaldehyde out-performed other fixatives. Long term fixation was not proposed for DNA/RNA-based assays. The typical long-term fixation of cells and tissues in 10% buffered formalin is not optimal for combined analyses by in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, or -if one does not have unfixed tissues - solution phase PCR. Rather, we recommend short term less intense cross linking fixation if one wishes to use the same cells/tissue for in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and solution phase PCR.

Keywords: in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, fixation, microRNA, real-time PCR, EBV, Papillomavirus

Introduction

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization are the methods used for assessing antigen and DNA/RNA expression within intact cells. A critical factor for both in situ hybridization and IHC is fixation. Selecting the optimal fixation method is challenging because of the disparate end results of morphologic, DNA, RNA, and in situ protein analysis plus the need, in cases, to also do solution phase analyses of the extracted nucleic acids. RNA extraction and analysis from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues still remains a challenging issue, Some investigations found HPV DNA could be detected from paraffin-embedded fixed tissue but some fixatives may compromise HPV type detection by dot blot or in situ hybridization (Nuovo et al. 1988). The optimized method of mRNA isolation and pre-fixation time (time from excision to fixation) were also estimated by TaqMan real time PCR. They found mRNA was insensitive to prefixation times of up to 12 hours and it was feasible to analyze gene expression in archived tissues where tissue collection procedures are unknown (Godfrey et al. 2000). Another group used formalin and other two commercial fixatives and found formalin is suitable for molecular biology assays as well as IHC (Nykänen et al. 2010). (Nuovo et al. 1988, Godfrey et al. 2000, Srinivasan et al. 2002, Nykänen et al. 2010).

It is estimated that viruses are etiological agents in approximately 12% of human cancers. Most of these cancers can be attributed to infections by human papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (Schiller J et al. 2010). EBV was identified as the first human tumor virus associated with several malignancies, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders arising in immune compromised individuals. Bovine papillomaviruses (BPV), homologous to HPV, are DNA viruses inducing hyperplastic benign lesions of both cutaneous and mucosal epithelia in cattle and horses.

This paper analyzed the situation where the researcher had limited cells or tissues and wished to determine what cross linking or denaturating fixative would allow for optimal in situ and solution phase analyses. We used EBV and BPV-infected tissues and cells as our model systems to evaluate the effects of nine different fixation approaches on the detection of viral antigens by immunohistochemistry, detection of DNA/RNA by in situ hybridization, and DNA/microRNA by real-time PCR.

Materials and methods

Materials

All blood and tumor samples were obtained following informed consent detailed in a protocol approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. NIH 3T3, JeKo cell lines and BPV2 plasmid were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). C7M3 is an EBV positive lymphoblastoid cell line generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a healthy donor in our lab. The Granta cell line was derived from a human mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patient and is known to be EBV positive. JeKo is a MCL cell line established from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a patient with a blastic variant of MCL showing leukemic conversion and is negative for EBV. All cell lines cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in DMEM or PRMI1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin solution.

FirstChoice Human Total RNA Survey Panel, U6 snRNA reverse transcript and TaqMan microRNA real time PCR kit was obtained from Ambion/Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). Lipofectamine 2000 and Trizol were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The BZLF1-specific monoclonal antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Tom Liu (Ohio State University) and the pre-diluted LMP1 antibody was obtained from Ventana Medical Systems (Oro Valley, AZ). QIAamp DNA mini kit ordered from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). The miR125b and 5S RNA TaqMan probes were designed according to the principle of stem loop PCR with modification and synthesized by Applied Biosystems. The concentration of DNA was estimated by spectrophotometry using the NanoDrop ND-1000 device (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Cytofix buffer was obtained from BD Biosciences (Sparks, MD). Methanol free paraformaldehyde was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). BPV positive tumor sample was kindly provided by Dr. Gerard Nuovo (Ohio State University, the tumor tissue was obtained from a squamous cancer of the penis of a BPV infected horse).

Immunohistochemistry

Nine different methods were used to fix the cells to determine the optimal condition for the process. These conditions are as following:

Non-cross linking fixatives:

Acetone Fixation (denaturing fixative, cytoskeletal, viral and some enzyme antigens usually give optimal results when cells are fixed with acetone.): Fix cells or tumor tissue in −20°C acetone for 10 minutes.

Methanol Fixation (denaturing fixative, used for cytogenetic analysis): Fix cells or tumor tissue in −20°C methanol for 10 minutes.

Methanol-Acetone Fixation (commonly used for immunofluorescence staining of cell preparation): Fix cells or tumor tissue in cooled methanol, 10 minutes at − 20 °C, remove excess methanol, and permeabilize with cooled acetone for 1 minute at − 20 °C. Cross linking fixatives

Formalin Fixation (cross-linking fixative, used routinely in the surgical pathology lab): Fix cells or tumor tissue in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight, rinse briefly with PBS.

Formalin Fixation: Fix cells or tumor tissue in 5% neutral buffered formalin overnight, rinse briefly with PBS.

Paraformaldehyde-Triton Fixation (cross-linking fixative, commonly used for immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization): Fix cells or tumor tissue in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, rinse briefly with PBS, and permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

Paraformaldehyde-Methanol Fixation: Fix cells or tumor tissue in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, rinse briefly with PBS, permeabilize with cooled methanol for 10 minutes at − 20 °C.

Cytofix Fixation (commercially available for intracellular staining of cells detected by flow cytometry): Fix cells or tumor tissue in Cytofix buffer (Cytofix Buffer is comprised of a neutral pH-buffered saline that contains 4% w/v paraformaldehyde) on ice for 20min, rinse with PERM/WASH buffer.

Formalin Fixation: Fix cells or tumor tissue in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 30 minutes, rinse briefly with PBS, permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

JeKo, Granta, and C7M3 cells lines were fixed by nine different fixation methods mentioned above. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Ventana Benchmark system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) and the ultraview universal Fast Red kit, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Optimal titrations for BZLF1 and LMP1 antibodies were determined to be 1:50 and 1:1 dilutions, respectively, with CC1 (antigen retrieval) for 30 minutes using EBV positive lymphoma and benign, reactive lymph nodes as the positive and negative controls, respectively. Counterstain was hematoxylin II for 4 minutes. JeKo cell line is known to be EBV negative and served as negative controls.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed according to the previously published protocol (Nuovo, 2006; Nuovo, 2008). Briefly, two-three 4-μm thickness tissue sections of each case were placed sequentially on each positive charged slide. The sections were deparaffinized, digested by pepsin (DAKO, 1.3 mg/ml) for 20 minutes, washed in sterile water, then 100% ethanol, and air dried. The fluorescent-labeled EBV RNA probes (EBERs 1 and 2) were kindly provided by Ventana Medical Systems. The probes were diluted to a concentration of approximately 0.5 mcg/ml using the Enzo in situ hybridization buffer. By placing 2 sections on a given slide, we could analyze sequential sections for EBER-1/2 and the negative control (no probe, or a plasmid only probe). The EBV probes and tissue RNA were co-denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes. Then, the slides were incubated overnight at 37°C. This was followed by a wash in a solution of 0.2XSSC with 2% BSA at 60°C for 10 minutes. The fluorescent -labeled probes were detected via alkaline phosphatase-anti-fluorescent conjugate (incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes) from Enzo Life Sciences. The alkaline phosphatase acts on the chromogen nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and bromochloroindolyl phosphate (BCIP) to form a bluish-purple precipitate in the nuclei, which indicated the presence of the specific probe-target DNA complex. Nuclear fast red served as the counterstain.

| TaqMan microRNA (miRNA) Real time PCR primers and probes |

| miR-125b F: 5′-GCCCTCCCTGAGACCCTAAC-3′ |

| miR-125b R: 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′ |

| miR-125b probe: FAM- TGGATACGACTCACAAGT-MGB. |

| BPV-2 DNA F: 5′-CTGATGCACCCGATTTCAGA-3′ |

| BPV-2 DNA R: 5′-AGAGGGACCTCGCTTCCTAGTAG-3′ |

| BPV-2 DNA probe: FAM – TTCCGTGCCATTTCGGCCGT -TAMRA |

| 5s RNA RT primers |

| 5′GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGCCTACA GCA-3′. |

| 5s RNA-F: 5′-TGATCTCGGAAGCTAAGCAGG-3′, |

| 5s RNA-R: 5′-GGCGGTCTCCCATCCAAG-3′. |

| 5s RNA probe: (6-VIC)TCGGGCCTGGTTAGT-(MGB) |

The detection of miRNA involved two steps (Chen C et al. 2005): reverse transcription and real time PCR. We used SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen 18080-051) for 5s RNA and miR125b Reverse transcription (RT). RT reactions contained 50ng total RNA, 100 nM stem–loop RT primer, 1×RT buffer, 1 mM each of dNTPs, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 2 U/μl RNaseOUT, 10 U/μl SuperScript III RT. We used TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems 4366596) for U6 snRNA RT. RT reactions contained 50 ng total RNA, 1 ×RT primer, 1×RT buffer, 1 mM each of dNTPs, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 0.3 U/μl RNase Inhibitor, 3.4 U/μl MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase. The 20 μl reactions were incubated in an MJ DNA Engine Thermocycler for 30 min at 16°C, 30 min at 42°C, 5 min at 85°C and then held at 4°C.

Real-time PCR was performed using a TaqMan 2 × Universal PCR Master Mix kit on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Sequence Detection System. The 10 μl PCR reaction included 1 μl RT product, 1×TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 0.2 μM TaqMan probe, 0.5 μM forward primer and 0.5 μM reverse primer or 20 × TaqMan primers and probe (Applied Biosystems). The reactions were incubated in a 384-well plate at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The threshold cycle (Ct) is defined as the fractional cycle number at which the fluorescence passes the fixed detection threshold.

Results

Expression of viral protein and RNA in cultured cells treated with different fixation methods

CELLS

Two EBV positive cell lines (Granta and C7M3) and one EBV negative cell line (Jeko) were fixed by nine different methods and two EBV antigen markers (membrane protein LMP1, and nuclear protein BZLF1) were stained by IHC as described. Epstein-Barr encoded RNA (EBER) was detected by in situ hybridization.

Microscopic evaluation was used to compare the effect of different fixatives on the morphology of cells. Cytofix and paraformaldehyde preserved cell morphology better than formalin or non cross-linking fixatives such as acetone and methanol (Table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of nine different fixatives on the cell morphology, LMP1 and BZLF1 signal intensity and signal localization by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and quality of miRNA and DNA. Cell morphology was scored as poor, good, excellent, the signal intensity of IHC was graded from 0–3, signal localization of IHC was scored as poor/diffuse/sharp, and in situ hybridization/miRNA/DNA was scored as excellent/acceptable/not acceptable by an independent pathologist.

| Fixation methods | cells |

tissue |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| morphology of cells (H&E) | Signal strength (IHC) | Signal localization (IHC) | In situ hybridizati on (cells) | In situ hybridization (tissue) | miRNA by solution phase PCR | DNA by solution phase PCR | |

| Acetone | poor | 0 | poor | Not acceptable | Not acceptable | excellent | excellent |

| Methanol | good | 1 | poor | Not acceptable | Not acceptable | excellent | excellent |

| Methanol-Acetone | poor | 1 | poor | Not acceptable | Not acceptable | acceptable | excellent |

| 10% Formalin overnight | good | 2 | diffuse | excellent | acceptable | Not acceptable | Not acceptable |

| 5% Formalin overnight | good | 2 | diffuse | excellent | excellent | Not acceptable | Not acceptable |

| Paraformaldehyde- Triton X-100 | excellent | 3 | sharp | Not acceptable | excellent | acceptable | excellent |

| Paraformaldehyde- Methanol | excellent | 3 | sharp | Not acceptable | acceptable | acceptable | excellent |

| Cytofix | excellent | 3 | sharp | Not acceptable | Not acceptable | acceptable | excellent |

| 10% Formalin- Triton X-100 | excellent | 3 | sharp | excellent | Not acceptable | acceptable | acceptable |

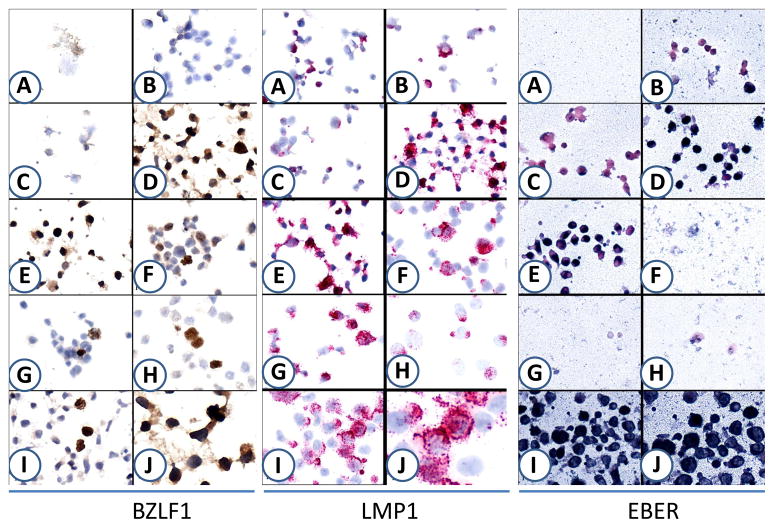

Fig.1.

Nine different approaches were used to fix the EBV positive C7M3 cells to determine the optimal approaches for in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. BZLF1 (left panel) and LMP1 (middle panel) were detected by IHC while EBER (right panel) was detected by in situ hybridization. A: Acetone; B: Methanol; C: Methanol-Acetone; D: 10% Formalin overnight; E: 5% Formalin overnight; F: Paraformaldehyde-Triton X-100; G: Paraformaldehyde-Methanol; H: Cytofix; I: 10% Formalin +Triton X-100. J. Enlarge of D for BZLF1 staining; enlarge of I for LMP1 and EBER staining.

Acetone fixation was not suitable for IHC staining and in situ hybridization because this led to destruction of cellular morphology. Paraformaldehyde and Commercially available Cytofix buffer (4% w/v paraformaldehyde) preserved cell morphology and enhanced specificity. For example, we consistently noted positive staining signal of the EBV lytic protein BZLF1 as well as high background signal in EBV negative cells (Jeko) when fixed in 10% formalin but not paraformaldehye or cytofix buffer. Paraformaldehyde and Cytofix buffer seemed to be superior to other fixation methods for cell preparations for IHC staining of nuclear protein such as BZLF1 (Fig. 1, left panel). However, for enhanced staining and evaluation of membrane proteins like LMP1, paraformaldehyde fixation followed by 10min of Triton X-100 permeabilization was found to be superior to other fixatives (Fig. 1, middle panel, and table 1). Similar results were observed in Granta, another EBV-positive cell line (data not shown).

For in situ hybridization, 10% formalin with or without Triton X-100 was the optimal condition for evaluation of EBER (Fig. 1, right panel). Fixation time (30 min vs overnight) had no significant impact on quality of in situ hybridization of EBER 1–2.

Expression of BPV DNA and host miRNA following tumor tissue fixation by nine different methods

TISSUES

We next evaluated the effect of different fixation conditions on BPV positive tumor tissues and cells. We examined the effect of fixatives on the cellular morphology and also on DNA/RNA quality. The BPV positive tumor tissue was fixed by the same nine fixation methods described above, and the influence of different fixatives and fixation time on BPV nucleic acids was examined by in situ hybridization, quantitative PCR and host miRNA quantitative real-time PCR.

in situ hybridization

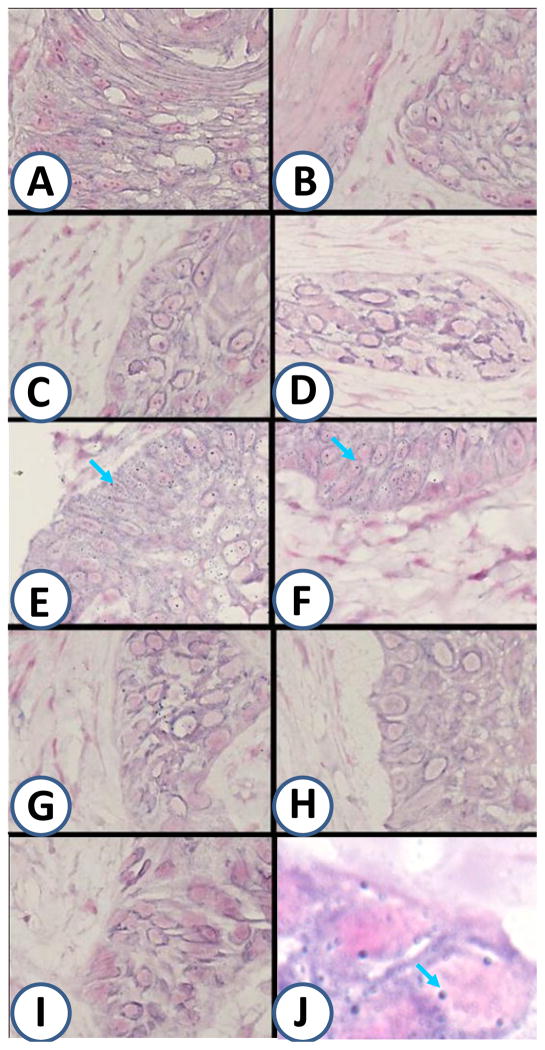

Dilute formalin (5% formalin) or light fixation (paraformaldehyde followed by Triton X-100 permeabilization) were found to be the optimal conditions for in situ hybridization for tissue preparation of BPV (Fig. 2E, F, blue arrows), the other fixatives had less staining with associated increase in background.

Fig.2.

Nine different approaches were used to fix the BPV positive tumor tissue to determine the optimal fixation for in situ hybridization of BPV. A: Acetone; B: Methanol; C: Methanol-Acetone; D: 10% Formalin overnight; E: 5% Formalin overnight; F: Paraformaldehyde-Triton X-100; G: Paraformaldehyde-Methanol; H: Cytofix; I: 10% Formalin +Triton X-100. J. Enlarge of E for in situ gybridization of BPV. Blue arrows point to representative positive signals (Blue dots).

Expression of BPV DNA and host miRNA in BPV positive tissues by real-time PCR

TISSUES

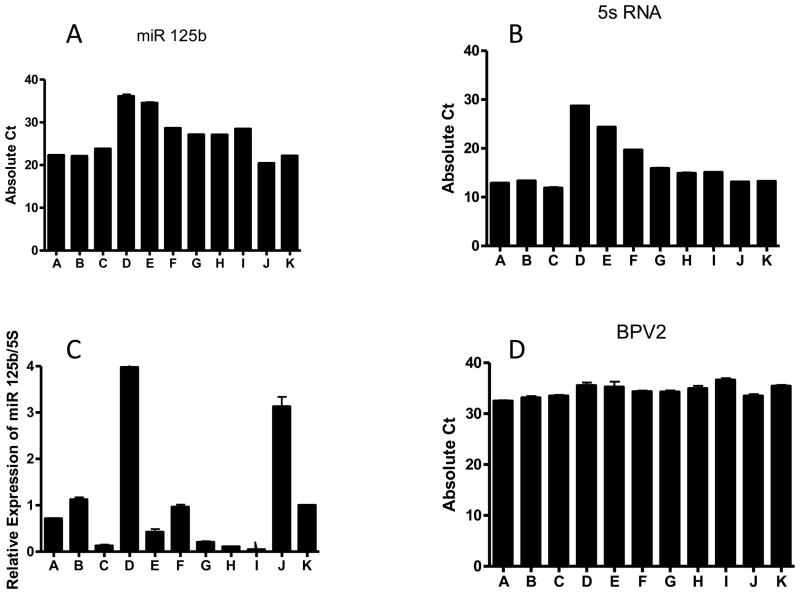

The Ct (cycle threshold) values of miR-125b and internal control 5s RNA, and relative miR-125b expression was calculated by normalizing with 5s RNA (Fig.3). We chose miR-125b since our previous work had shown dramatic reduction of miR-125b in koilocytes present in CIN 1 (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) lesions suggestive that BPV may regulate miR-125b (Nuovo GJ, et al. 2010). Different fixation methods were associated with alterations of the Ct values and thus changed detection sensitivity. Acetone, methanol and paraformaldehyde preserved both miR-125b and 5s RNA expression better than formalin (Fig. 3A, 3B). In terms of relative miR-125b expression after normalization with 5s RNA (Fig. 3C), paraformaldehyde, acetone, and methanol fixation methods were among the best choices. Long term formalin fixation (overnight) not only decreased the total RNA quality but also altered expression patterns. Similar results were also achieved with NIH 3T3 cells transfected with BPV DNA (data not shown). These results indicated that denaturing or short term cross linking fixatives were prefered on miRNA detection.

Fig.3.

The expression of miRNA in BPV positive tumor tissues fixed with nine different fixatives. (A) The Ct value of miR125b; (B) The Ct value of 5s RNA control; (C) relative expression of miR125b after normalized with 5s RNA; and (D) The Ct value of BPV DNA. A: Acetone; B: Methanol; C: Methanol-Acetone; D: 10% Formalin overnight; E: 5% Formalin overnight; F: Paraformaldehyde-Triton X-100; G: Paraformaldehyde-Methanol; H: Cytofix; I: 10% Formalin +Triton X-100; J: Frozen adjacent normal skin; K: Frozen BPV positive tumor tissue.

To observe the effect of fixation on the DNA preservation, we isolated DNA from the BPV positive tumor tissue and detected viral DNA by TaqMan real time PCR (Fig. 3D). Different fixation approaches did not affect BPV DNA detection significantly although the denaturing fixatives gave slightly better results. However, both the quality and yield of total RNA/DNA determined by spectrometer isolated from the formalin fixed overnight group were considerably low (data not shown).

Discussion

Fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues are increasingly being used as a source of materials for molecular assays in addition to histopathological morphology evaluations (Gillespie et al., 2002 and Godfrey et al., 2000). Many variables may influence the quality of biomolecules (Walker et al, 2006; Bussolati et al, 2008; Titford et al, 2005), which has led to potential incorrect interpretations. Therefore it is imperative to optimize methods of specimen preservation. This will ensure that satisfactory information can be extracted from the fixed biomolecules in tissue. Length and type of fixation may not only affect protein integrity but also may affect other molecular targets such as DNA and RNA (Werner et al. 2000; Srinivasan et al. 2002; Emmert-Buck et al. 2000). The purpose of this study was to examine how a wide variety of commonly used fixatives and fixation times affected morphology and integrity of biomolecules in tumor tissues and cultured cells.

10% buffered formalin fixed for 4–15 hours is the standard for the surgical biopsies commonly used for human molecular based studies. Our data shows that such fixation may negatively impact on in situ hybridization and solution phase PCR. Prolonged formaldehyde fixation may generate free aldehyde groups in sections resulting in non-specific binding of antibodies and formaldehyde may also alter the tertiary and quaternary conformation of proteins and deter the link to antibodies. Our results showed that for tumor tissue, either low concentration of formalin (5%) or weak cross linking fixative such as paraformaldehye is superior to other fixatives for in situ hybridization. We recommend if ones have the ability to fix research tissues directly for the purpose of in situ hybridization, low concentration of formalin or weak cross linking fixatives is superior to the traditional 10% buffered formalin. Longer fixation may make proteins, DNA, and RNA more difficult to detect in situ because of more extensive protein-target cross hybridization with loss of “detectable” or “unexposed” target, this problem can be solved by increased protein crosslink destruction by either increased protease digestion or increased time in cell conditioning, we tried to enhance protein/DNA/RNA detection in the longer fixed samples by analyzing increased protease digestion time and it helped to enhance the signal of in situ hybridization.

We also determined that for cell preparation, short-tem formalin and paraformaldehyde fixatives are suitable for IHC. However for in situ hybridization of cell preparation, short or long fixation of formalin was superior to other fixatives. The cells were over-digested in non-formalin fixatives. We optimized in situ hybridization protocol for formalin-fixed cell preparation suggests that the conditions for in situ hybridization need to be further optimized when considering fixatives other than formalin.

PCR techniques allow the use of small quantities of DNA/RNA. In formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples it is important that nucleic acid be extracted by a suitable method. Godfrey et al. (2000) found that approximately 1/30 of RNA isolated from FFPE samples was accessible for cDNA synthesis in reverse transcription reactions. Our results showed that for tumor tissue, acetone, methanol and a weak cross linking fixative such as paraformaldehyde preserve DNA/RNA better than strong cross linking fixatives. In our study Ct values in tumor samples fixed with acetone and methanol were comparable to frozen tissue and lower in samples fixed with other fixatives. Paraformaldehyde, acetone and methanol fixations were among the best choices for relative miR-125b expression after normalization with 5s RNA. 5s RNA is a small non-coding RNA transcribed by RNA polymerase III and it is a reliable internal control for the normalization of miRNA (Haurie V et al., du Rieu MC et al). Our results showed that the expression of 5s RNA is consistent across different types of human tissues comparing with U6 snRNA (data not shown). We also showed that for cell preparation methanol, paraformaldehyde and short fixation by formalin preserve DNA/RNA better than strong cross linking fixatives. Our data suggests that for tumor tissue prepared for IHC, in situ hybridization, and molecular techniques such as DNA/RNA extraction and real-time PCR of miRNA, a weak cross linking fixative, such as paraformaldehyde is superior to other fixative methods. For IHC, in situ hybridization, and molecular techniques in cell preparations, fixation with a weak cross linking fixatives or a short fixation with 10% buffered formalin is optimal.

In summary, the current study examined nine different fixation regimens for optimal conditions with IHC, in situ hybridization, and real-time PCR of DNA/RNA. We have identified specific fixative methods for IHC, in situ hybridization, and real-time PCR of DNA/miRNA. We would advocate that as novel fixation techniques are developed, their suitability for IHC, in situ and real-time PCR be established.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Gerard Nuovo for providing tumor tissue samples, for his generous help with the immunohistochemistry staining and in situ hybridization, and for all the ideas and techniques for this paper. We thank Dr. Margaret Nuovo for her wonderful work editing the images. This work was supported by NCI grant P30 CA016058 to the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, Barbisin M, Xu NL, Mahuvakar VR, Andersen MR, Lao KQ, Livak KJ, Guegler KJ. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(20):e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Rieu MC, Torrisani J, Selves J, Al Saati T, Souque A, Dufresne M, Tsongalis GJ, Suriawinata AA, Carrère N, Buscail L, Cordelier P. MicroRNA-21 is induced early in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma precursor lesions. Clin Chem. 2010 Apr;56(4):603–12. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert-Buck MR, Strausberg RL, Krizman DB, et al. Molecular profiling of clinical tissue specimens: feasibility and applications. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64979-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JW, Best CJ, Bichsel VE, Cole KA, Greenhut SF, Hewitt SM, Ahram M, Gathright YB, Merino MJ, Strausberg RL, Epstein JI, Hamilton SR, Gannot G, Baibakova GV, Calvert VS, Flaig MJ, Chuaqui RF, Herring JC, Pfeifer J, Petricoin EF, Linehan WM, Duray PH, Bova GS, Emmert-Buck MR. Evaluation of non-formalin tissue fixation for molecular profiling studies. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64864-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey TE, Kim SH, Chavira M, Ruff DW, Warren RS, Gray JW, Jensen RH. Quantitative mRNA expression analysis from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using 5′ nuclease quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Mol Diagn. 2000;2:84–91. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60621-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurie V, Durrieu-Gaillard S, Dumay-Odelot H, Da Silva D, Rey C, Prochazkova M, Roeder RG, Besser D, Teichmann M. Two isoforms of human RNA polymerase III with specific functions in cell growth and transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Mar 2;107(9):4176–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914980107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuovo GJ, Silverstein SJ. Comparison of formalin, buffered formalin, and Bouin’s fixation on the detection of human papillomavirus DNA extracted from genital lesions. Lab Invest. 1988;59:720–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuovo GJ. The surgical and cytopathology of viral infections: utility of immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and in situ polymerase chain reaction amplification. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10(2):117–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuovo GJ. In situ detection of precursor and mature microRNAs in paraffin embedded, formalin fixed tissues and cell preparations. Methods. 2008;44(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuovo GJ, Wu X, Volinia S, Yan F, di Leva G, Chin N, Nicol AF, Jiang J, Otterson G, Schmittgen TD, Croce C. Strong inverse correlation between microRNA-125b and human papillomavirus DNA in productive infection. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2010 Sep;19(3):135–43. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181c4daaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykänen M, Kuopio T. Protein and gene expression of estrogen receptor alpha and nuclear morphology of two breast cancer cell lines after different fixation methods. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2010;88( 2):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titford ME, Horenstein MG. Histomorphologic assessment of formalin substitute fixatives for diagnostic surgical pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:502–506. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-502-HAOFSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Vaccines To Prevent Infections by Oncoviruses. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010 Apr 26; doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M, Sedmak D, Jewell S. Effect of fixatives and tissue processing on the content and integrity of nucleic acids. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RA. Quantification of immunohistochemistry-issues concerning methods, utility and semiquantitative assessment. Histopathology. 2006;49:406–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M, Chott A, Fabiano A, Battifora H. Effect of formalin tissue fixation and processing on immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1016–1019. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]